Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

414 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

or lectern.

32

But the political authorities, at least in Austria, were very slow to

act with any complementary civilian action. At the FA ministerial discussions

on 13 July, a representative from the office of the Austrian Prime Minister had

at best been able to say that a civil action was `imminent', although purely of a

private, non-official character. A month later, the FAst complained to Baden

that nothing had yet materialized, yet now was the ideal moment since enemy

aeroplanes had just showered Vienna with manifestos; this needed to be coun-

tered with

a methodical campaign of `resistance-propaganda' in which all

organizations and classes, all nationalities and parties of the hinterland would

take part.

33

It slowly emerged that the Austrian Ministry of Interior was begin-

ning to

plan such a campaign but was constrained by financial considerations.

By late September the lack of progress had reached the ears of the press. Taking

up the baton which the Corriere della Sera had run with in Italy eight months

earlier, the Vienna Reichspost proclaimed that it was time to move beyond the

preparatory stage by setting up an `Austrian propaganda centre':

It will

be a responsible position which the propaganda chief assumes. If he

understands his job, he can do more for Austria than ten ministers or one

army, in other words he can spare Austria the blood of a whole army. We

seek Austria's salvation not in lies, like England when it appointed North-

cliffe ±

the world master of lies ± as its agent, but in truth, in the Austrian

truth. The truth has to be preserved so that it does not drown in the enemy's

flood of lies.

34

It was the kind of statement which Northcliffe himself might have made. It

showed that, among Austrian journalists at least, Northcliffe retained a power-

ful reputation

as the man who had the predominant role in enemy propaganda

because of his newspaper empire. The Reichspost repeated a rumour that an

Austrian newspaper editor, Leopold von Chlumecky, might be about to assume

the role of a `Northcliffe' for the Monarchy. The reality was that, with a million

crowns finally placed at its disposal, the Austrian Ministry of Interior had

decided to organize everything under its own auspices, appointing an official,

Hofrat Robert Davy, to head a `civilian propaganda centre'. On 8 October, the

AOK agreed that Egon von Waldsta

È

tten, Max Ronge and the head of the KPQ ,

Eisner-Bubna, would help Davy to set up a propaganda committee.

35

At this late stage few of those involved were under many illusions. As Eisner-

Bubna observed, `in order to begin suitable domestic propaganda, a clear polit-

ical goal

must first be established', and they would inevitably be bowing before

existing realities:

Priests, teachers,

writers and politicians of the different nationalities are all

contributing to a situation where the nationalist goals of the native races

Disintegration 415

take precedence over the imperial ideal . . . Considering the degree of dis-

organization already

present, the goal of domestic propaganda can only be

to hold the various nationalities together in a looser association. It can

certainly not be a goal of domestic propaganda to try to preserve existing

conditions, for this would rapidly cause internal antagonism.

36

The leaders of patriotic instruction, whether in the hinterland or the war zone,

were therefore hoping that they might still appeal to some latent concept of

Staatsgedanken among broad swathes of the population. Then at least, even if

the main goal of VaterlaÈndischer Unterricht

had failed (as they recognized), it

might yet be possible to preserve public order and perhaps even some form of

Habsburg state entity.

9.2 A final duel in front propaganda

Just as the Austrian military had tended to view Italy's campaign of 1918 as

really `counter-propaganda' to the campaign which they had started after

Caporetto, so they always felt that to continue their own efforts against Italy

was a necessary extra dimension to their `enemy propaganda defence'. The

battle of ideas across the front could never be wholly surrendered to the

enemy, even if temporarily one side might be in a more advantageous position.

Thus, although the Austrian military had acknowledged after the June offensive

that their campaign had failed and would accordingly be scaled-down as more

effort was put into ideological defence, it would not be abandoned altogether.

As Baden explained in new guidelines issued to the armies on 4 August, `the

effect of propaganda changes according to the momentary military and moral

situation. At present its basis is unfavourable for us, but the time may come

when the propaganda weapon employed so successfully in other theatres of war

may also render good service against Italy.' The chief aim was to maintain some

pressure on the Italians, by encouraging thoughts of peace, while waiting for a

change in fortune for the Central Powers. As usual one might also hope that

front propaganda would then (as in Russia) have some indirect impact in the

Italian hinterland.

37

With these thoughts in mind, all the Austrian armies continued some pro-

paganda against

Italy over the summer, working largely on their own initiative

while following the basic AOK directive. Their efforts, however, were to be

limited as much by technical obstacles as by their own self-imposed restraints.

Since Italian vigilance was so strong, the AOK forbade personal contact; and the

depositing of material, a favourite method of the past, was also viewed as less

promising. Instead the material was to be spread from the air, where the

Austrians were distinctly inferior, or by special rockets which were always in

short supply to the propaganda personnel. Given too the shortage of paper

416 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

available to the armies, and even though it was common practice for the

propaganda officers to exchange their material with neighbouring armies, it

was not surprising that the distribution in these months was minuscule. In

August, while KISA sent out 15 300 pieces of propaganda (in comparison to

500 000 in May), the 11AK was even more hesitant with only 2450 pieces to its

name. The 10AK might muster a figure of 100 000 for the same month, but this

should be compared with the 100 000 or more leaflets which the Italians were

scattering every day.

38

If the Austrians' material was not reaching its target, their arguments were

nevertheless quite sound and, as the AOK rightly noted, might have been

capable of bearing fruit if Italy's military position had been weaker. In line

with the guidelines, they paid particular attention to the issue of the Czecho-

slovak Legion,

not simply through `disinformation' with the D.R.U.P. messages,

but also by openly appealing to the Italian soldier's sense of honour and

decency in permitting himself to rub shoulders with such individuals `of base

and vile character'.

39

Those Italians who were under the illusion that they were

fighting for `freedom' or the `oppressed nationalities' could be given the same

argument as that of Austria's patriotic instruction, that the Allies were hypo-

crites. A

leaflet from the 6AK, for example, reported a declaration by Indian

nationalists criticizing Theodor Roosevelt for urging freedom for peoples in

central Europe while making no mention of the `oppressed and tyrannized

Indians, Irish, Egyptians, African Boers, Philippinos, Koreans, etc'.

40

Alongside

this, the material tried to suggest the real bleakness of `Italy's war', recalling a

host of arguments which had been used earlier in the year. Italy had lost over

two million men and 50 000 million lira, and was now continuing the war

simply to satisfy the imperialist ambitions of the English and American

capitalists. The country was fast becoming an Allied colony, for already `Son-

nino and

Orlando have to dance to the tune of Wilson's and Lloyd George's

orchestra'.

41

If the Austrians felt justifiably that there was still some potential in this line

of argument on the basis of their own Intelligence sources, their assertion that

Italy and its Allies were about to lose the war had naturally lost its force after

July 1918 as the Germans retreated on the Western Front. There might be a few

hopeful signs, such as General Pflanzer-Baltin's brief success in Albania,

42

but

otherwise the Austrian propagandists had insufficient material to work with.

Despite many subtle touches in their leaflets, they could never secure from the

Italian press the same kind of subversive evidence which Padua was able to

exploit so fully for its own purposes. Similarly, any propaganda which dwelt too

heavily upon Austria-Hungary's own strengths or stability had begun to sound

hollow by the late summer; such was a leaflet widely circulated from the 11th

army sector which tried to suggest that the Monarchy with its peoples `united

and well-fed', would not be destroyed in a hundred years.

43

A more profitable

Disintegration 417

line, undoubtedly, was simply to dwell on the Italian soldier's desire for peace,

emphasizing that Austria-Hungary wanted a peace which was just and lasting;

it could be made immediately, as the Monarchy was fighting a defensive war

with no claims upon Italian territory.

44

These efforts became more urgent from mid-September as Austria-Hungary

began to make concrete proposals for peace to the enemy. The campaign was

stepped up and returned to the overall control of Max Ronge's Intelligence

section. Until then Ronge had only been responsible, in propaganda terms, for

smuggling material into the Italian hinterland via Switzerland, a route which

had always been difficult to keep open; but it was perhaps especially due to

Ronge's experience with `peace propaganda' on the Eastern Front that the AOK

now expanded his mandate. In his memoirs, Ronge tells how he quickly set up

a special propaganda centre in Baden, sensing that the desire for peace in the

enemy camp would offer several clear `lines of attack' with the propaganda

45

weapon. In fact, the main aim of Austria's revitalized campaign had now

changed. Its purpose was not so much to demoralize the Italians as a prelude

to some future military success, but to achieve an end to the war as soon as

possible before the Monarchy itself disintegrated.

On 5

September, the Foreign Minister Count Buria

Â

n, with an eye on the det-

eriorating economic

situation, had informed Germany that Austria-Hungary

could not wait `until the roasted dove of peace flies into our mouth'. On 14

September, despite German protests, he went ahead and dispatched to all

belligerent states a note proposing discussions for peace.

46

At the front, Aus-

trian planes

and propaganda patrols began to spread manifestos reporting this

`sincere offer' made in accordance with the wishes of `the people', and pressing

Italian soldiers to demand that their government accept the proposal; after all,

was it not time to end a war which `neither side could win'?

47

The Austrians

were anxious to find out whether their arguments were having some immediate

effect, but because of the lack of fraternization, or of Italian prisoners or

deserters, such an inquiry proved impossible.

48

In fact, news of Buria

Â

n's note,

whether learnt from Austrian propaganda or from the Italian press, seems to

have caused quite a stir in Italian military circles. Ugo Ojetti was worried lest

`naõ

È

ve talk of an armistice' might lead to another Caporetto. He himself speed-

ily composed

for enemy troops some blunt replies which reflected, or perhaps

even anticipated, the Allied governments' rejection of Buria

Â

n's offer: the Habs-

burg Monarchy,

`the originator of the world conflagration . . . penitently strews

its head with ashes and asks for peace. However, the first question which strikes

every decent man is, can one pardon a criminal who has no equal in history?'

The hand which Austria offered was the `hand of an imposter which even at

this critical moment has not laid aside his inborn shifty habits'. The Entente

would not make peace with the old Austria, those who wanted to impose a new

type of Brest-Litovsk peace, but only with true representatives of the people,

418 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

those who were fighting for freedom and national independence. For this

reason, Padua declared, `the hour of peace has not yet struck'.

49

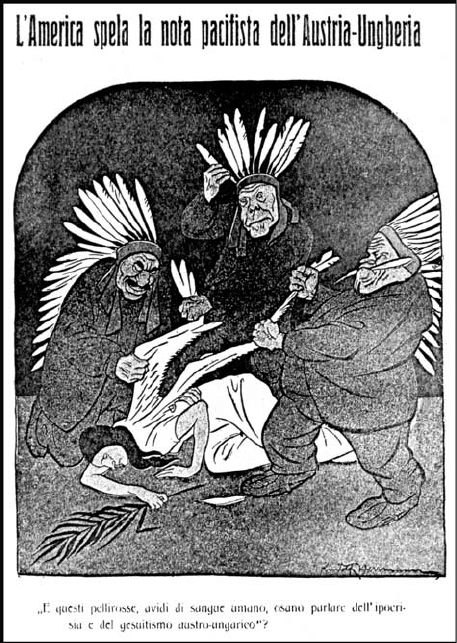

Responding to this, Austrian propaganda attacked the Italian government for

failing to meet the wishes of its own people, and the English and Americans for

hypocrisy. The latter, the first to officially reject Buria

Â

n's note, were portrayed

as fat American Indians who greedily plucked feathers from the Austrian dove

of peace in order to adorn their own headdresses (see Illustration 9.1).

50

From

4 October, however, Austria's `peace propaganda' had some new substance as

the Central Powers sent a joint note to Wilson, requesting peace on the basis of

his `Fourteen Points'. In a final set of guidelines issued a week later, Ronge

stressed that it was vital at this stage not to renounce what was the `most

modern weapon of warfare'. While the chances of an impact were not

too favourable, given the state of Italy's morale, it simply meant that `peace

Illustration 9.1 America rejects Buria

Â

n's peace offer: Austria's final effort at propaganda

against Italy (KA)

Disintegration 419

propaganda' had to be more subtly put across; the idea of peace had to be

carefully nurtured, building bridges to the Italians without arousing any resent-

ment, and

doing so through a resumption of `oral contact' across the

trenches.

51

The importance which the military leadership attached to this last

burst of front propaganda very much reflected the vain hopes which the rest of

the Habsburg elite were placing on a favourable reply from President Wilson.

When it did not come, and Wilson only replied to Germany, the front propa-

gandists still

interpreted this as an acceptance of Austria's offer, pending the

solution of `a few details'; no mention was made of the crucial absence of any

reply to Vienna.

52

Yet the manifestos assumed a more critical tone as the days went by. From

mid-October Ronge was sending out to the armies material which expressly

blamed the English and French for sabotaging Wilson's programme, while

highlighting the `pacifist demonstrations' which were allegedly occurring in

Allied countries.

53

Although these leaflets were distributed until the eve of

Italy's offensive (24 October) few appear to have reached their goal, nor was

there much time for any oral contact. For at the front it was the Allies' propa-

ganda campaign

which held sway. The Padua Commission duly treated the

Central Powers' offer of 4 October with the same disdain as Buria

Â

n's earlier

note. At first Ojetti was rather anxious, since Wilson's answer, if it adhered too

much to the `Fourteen Points', might seriously affect Italian territorial aspira-

tions. But

he eventually anticipated the American reply altogether and repeated

his claim that Wilson would only deal with the peoples, never with the old

rulers of Austria-Hungary.

54

It was a valid prediction, for on 19 October when

Wilson finally replied he effectively told the Habsburg elite that the future lay

in the hands of the Monarchy's various national leaders. With this announce-

ment, the

Austrians' peace programme through which they desperately hoped

to save the Monarchy at the eleventh hour lay in ruins. Their propaganda

campaign on the Italian Front, weak as it was, had also lost all impact, for the

Italians knew that they could achieve a victory over Austria-Hungary before the

war came to an end.

In the

propaganda duel in these final weeks of hostilities, the advantages

which Italy's campaign possessed in comparison to Austria-Hungary's could be

measured in almost every field. Although there were some on the Allied side

who worried that Italian troops might be too receptive to news of an imminent

peace (as the Austrians hoped),

55

the arguments in Padua's propaganda were far

more numerous and `newsworthy'. They were propagated widely, because Italy

controlled most of the avenues of distribution, and they were better coordin-

ated because

Italy's propaganda machine was largely centralized in one place. It

remained, moreover, Italy's campaign despite all the efforts of Crewe House. By

September, some new Allied representatives had been delegated to the Padua

Commission: the American G.H. Edgell and the Serbian liaison officer Major

420 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

Filip Hristic

Â

(this, perhaps, a reflection of Serbia's increasing influence to the

detriment of the Yugoslav Committee). But they appear to have had little

more impact than Baker and Gruss; even when Ojetti was absent for a few

weeks, his faithful lieutenants Donati and Zanotti-Bianco held the fort quite

competently. Ojetti himself appears to have written many of the manifestos in

the final months, using the national delegates largely as translators or advisers.

They in turn (lacking the vociferous Jambris

Ï

ak or Zamorski) seem to have fallen

in docilely or, to be more precise, fallen ill one after the other.

56

Ojetti's overall

control was further aided by the departure of Granville Baker in mid-October.

With the collapse of Bulgaria, a wider front had been opened against the

Monarchy, and Crewe House once again took the initiative by transferring

Baker to Salonika in order to establish a new propaganda commission on the

Balkan Front. On arrival there, Baker began to play the role which Ojetti had

successfully assumed in Padua. He had at last secured his own sphere of influ-

ence, with

a staff who would have included Jambris

Ï

ak. But it was a dream soon

overtaken by events.

57

Yet Ojetti himself was far from satisfied in the last months of the war. Apart

from a personal concern (his daughter, who was seriously ill), he had two major

interlocking anxieties which affected the efficiency of his work. First, he was

exasperated by the continuing ambiguity of Italian official policy. He had fully

supported the Corriere campaign against Sonnino and repeatedly pressed

Orlando to remove his foreign minister and conclude a special pact with

America for the destruction of Austria. The lack of a clear line, especially on

the Yugoslav issue, was enabling the naval and air authorities to obstruct leaflet

distribution, while at Padua some renewed tension was occurring with the anti-

Yugoslav Colonel Siciliani (officially head of the Commission) whom Ojetti

suspected of trying to assume control over his liaisons with the national coun-

cils, the

CS and the Intelligence offices.

58

On 23 September, at a war council,

Orlando furiously defended Ojetti to Sonnino and Diaz as his `confidant' who

was carrying out excellent work, and suggested that Siciliani should be

moved elsewhere; the attack appears to have weakened the latter's position

at Padua.

59

Yet Orlando's own `balancing act' in the Italian cabinet per-

sisted. His

delay in publishing Italy's Yugoslav declaration or in advancing

the case for a Yugoslav legion, and his refusal to speak out more decisively

in Parliament for the destruction of Austria as Ojetti requested ± all these

elements combined, in Ojetti's view, to weaken the potential of Padua's cam-

paign, as

well as weakening Italy's prime role as Allied leader of the oppressed

nationalities.

60

Ojetti's second major frustration was closely linked to this last point. By the

autumn he was increasingly concerned at the CS's delay in launching another

offensive against the enemy. The danger was that the Austrians might collapse

completely before Italy had attacked and gained the main credit for defeating

Disintegration 421

them. Ironically, therefore, near the end of the war, Ojetti ± the propagandist ±

wanted more traditional warfare to take over before the weapon of propaganda

should have too great an impact upon the enemy; the new weapon, in his eyes,

was a supplement but not a substitute for an armed attack which would `prove'

Italy's victory to the world. As it was, the Italians were discrediting themselves

with Britain and France, who were both pressing the CS to attack and comple-

ment the

successful offensive on the Western Front. In response, the CS in

September hesitated to act until Allied reinforcements, or a major setback for

the enemy on other fronts, could offset what they viewed as Austria's numerical

superiority against them. Diaz told Lord Cavan, `the Austrian is not ready to fall

down and be trampled on. He has shown good fighting qualities on several

occasions since his defeat in June.' This view persisted at the CS despite the

steady collapse of Bulgaria from mid-September.

61

One British officer on 25

September characterized well the mood in the war zone: `To sum up, the offens-

ive will

probably not take place, but on the other hand it may. Equally it may be

ordered and again cancelled.'

62

Only in early October, after the Bulgarian arm-

istice and

clear signs of success in the West, did Diaz and Badoglio finally decide

on an offensive. They may have been critically swayed by Italian Intelligence

sources. On 2 October, Tullio Marchetti, brimming with confidence after his

two Czech agents had returned from their adventure in Trento, presented the

CS and Orlando with a vivid picture of the reality behind the enemy facËade:

The Austrian

army in line is still strong but it cannot be supported from the

rear which is infected. It is like a pudding which has a crust of roasted

almonds and is filled with cream. The crust which is the army in the front

line is hard to break.

63

But if a hole was pierced in the crust at a suitable point, the cream or reserve

would be reached and the whole Austro-Hungarian army would melt away. It

was a fairly accurate prediction of what would happen three weeks later. Even

so, the Italian attack, delayed into late October because of rain which caused

the river Piave to swell, still came too late. As Ojetti, Orlando and others feared,

the confusion in the Monarchy had by then progressed too far for the Italians to

be able to claim convincingly that their offensive was the `decisive battle which

sealed the fate of Austria'.

64

In Italy's postwar history the myth of the traditional military victory (Vittorio

Veneto) would predominate. But at the time, in 1918, Italy's military and

political leaders had felt able to acknowledge the role which propaganda had

played in the de

Â

ba

Ã

cle.

As in June, so in September, the CS viewed propaganda as

a valuable preparation for Italy's attack as well as a temporary substitute for

taking too many risks. Therefore the period of mid-September onwards wit-

nessed an

intensification of Padua's campaign, with the Commission producing

422 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

264 new leaflets in about 15 million copies, twice the number issued in the

previous month but on a par with figures for the period during and immedi-

ately after

the June offensive.

65

How far this material reached its targets is

unclear. The paucity of copies of the later manifestos surviving in the archives

may suggest not only that many were lost in the chaos of the final retreat, but

that Austrian troops were failing to surrender the leaflets to the authorities. We

know, for example, that in the 10th army sector the average daily `intake' of

leaflets by September was only about 2000, while for the 11th army it was at

best 150±200. Ojetti at the end of the war was delighted when he came across

a battalion of captured Hungarians who retained a mass of his leaflets in their

possession.

66

In this final phase, the main theme of Padua's propaganda was Allied military

success in other theatres of the war. The material directed to different nation-

alities appears

to have become more uniform, and it is tempting to suggest that

this was due to Ojetti's dominance and his relegation of those national deleg-

ates who

previously had given the manifestos a more native stamp. It meant in

fact that the summer months had been the highpoint of inventiveness for the

material, but that time had now passed as the war of movement took over and

Padua found it more difficult to keep up with events. Great play was especially

made of Bulgaria's collapse and the armistice signed on 29 September with

General Franchet d'Esperay. In one commentary, Slovene soldiers were sup-

plied with

a common metaphor:

When the

ship sinks all the rats abandon it. Only Austria clings to the

wreckage of Germany. Only the Austrian rat is so mad that she does not

want to leave the sinking German ship on which she embarked to sail

through the rough seas of discontent of her peoples. In the end this is not

surprising: for she is old and stupid. It is better she dies.

67

Bulgaria's defeat opened the way for a rapid Allied advance into Serbia towards

the Hungarian frontier, enabling Padua to hint at the `threat' or `liberation'

which was about to ensue for Serbs, Romanians or Hungarians. At the same

time Turkey's links with the Central Powers had been severed. Since British

troops under Allenby were racing through Palestine, seizing Damascus and

75 000 prisoners by late September (one of Padua's more wild estimates), it was

`obvious' that the Ottomans were about to follow the Bulgarians' example.

68

In the West the news was equally gloomy for the Central Powers, causing the

German people to realize suddenly that they had been led by a `lunatic of

degenerate stock' who had the `fantasies of a diseased imperial mind'.

69

In

early September British troops had pierced the `Wotan line', recovering all the

territory taken by Germany since the March offensive. On 12 September,

American forces in one day had captured the St Mihiel salient, taking according

Disintegration 423

to Padua 5320 prisoners of the Austro-Hungarian 35ID (which incidentally now

became a target for Allied propaganda on that front, as Arz himself had

feared).

70

On 26 September, Marshal Foch had attacked the supposedly

impenetrable `Hindenburg line' in four places, broken through, and taken

40 000 prisoners in two days.

71

Padua portrayed the German retreat in the

West as being virtually uninterrupted since July. And in view of the success

on other fronts, not to mention the Italian advance in Albania or Bolshevik-

German reverses in Russia, the manifestos could justifiably proclaim that the

`day of wrath' (dies irae) had arrived for the enemy: `From east to west the

victorious song of the Allies overflows.'

72

The encirclement of the Monarchy and its inevitable defeat as `millions' of

Americans joined the fray were forceful realities which could still be balanced

with the idealistic message that victory for the Allies would mean freedom and

justice for all peoples in Europe. For the Yugoslavs, Italy's official statement

which Crewe House had managed to secure in September, was portrayed by

Ojetti as a `historic declaration . . . perhaps more important than any other

event of the war'. It was displayed in tricolour leaflets in Slovene, Croatian and

Serbian, which stated boldly that the Italians had now adopted as a war aim

the destruction of Austria-Hungary and the creation of a free and independent

Yugoslavia. Trumbic

Â

himself was quoted as usual, thanking Orlando for a

statement which represented `a new era in the relations of both peoples'.

73

Although this was indeed a new departure for Padua's Yugoslav propaganda,

the reality behind it was very different. Orlando remained ambivalent, while

Trumbic

Â

would soon perceive that Italy's words were just another example of

`throwing dust in the eyes of the Allies' for propaganda purposes: the Yugoslavs

had not been officially recognized by any of the western Powers as allies.

74

It

suited the Italian government to perpetuate this ambivalent stance, giving lip-

service to the Yugoslav cause, while aiming to implement the Treaty of Lon-

don as

soon as the war ended. In the last days of hostilities, it was a trend in

policy which speeded up. Some, like Gallenga Stuart, were inclined in the sight

of victory to fall in with the Orlando±Sonnino camp. Others like Borgese were

shocked at Italy's increasing divergence from the nationality policy of which

he had been a sincere adherent. In mid-November he would resign from the

Berne office as he refused to be the propagator abroad of a policy which would

set Italy at odds with America and the new nationalist states of eastern Europe.

75

Yet at the front, Padua's Yugoslav propaganda had always been more clearly

defined than was warranted by Italian policy. The discrepancy between Italian

policy and propaganda in 1918, the mask which Orlando had donned after

Caporetto to ease the path to victory, stored up a mass of resentment for the

future. It would erupt in earnest at the Paris Peace Conference, when the

claims of Italy and Yugoslavia were placed on an international stage, and it

bedevilled relations between the two countries for the next 20 years.