Canale L.C.F., Mesquita R.A., Totten G.E. Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

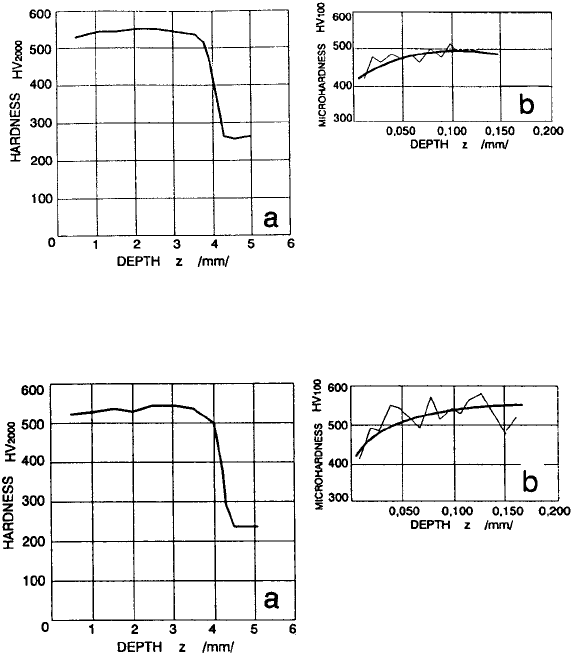

hardness across the entire hardened layer and the

microhardness in the very thin surface layer, the

latter were measured by the Vickers method.

Thus, Fig. 83 and 84 show the hardness profiles

versus the induction-hardened layer depth

according to Vickers at a load of 20 N or mea-

surements of microhardness according to Vick-

ers in a very thin surface layer to a depth of

150 mm at a load of 2 N (Ref 44).

The hardness of the surface layer after

induction surface hardening is very uniform in

all the investigated main bearing locations and

equals approximately 520 to 550 HV

2.0

. The

hardness profile highly conforms to the residual-

stress profile, which is confirmed by a decrease

in hardness in the transition zone. The hardness

profile in the transition area is likewise very

steep and points to high stress concentrations in

this location when the crankshaft is in the loaded

state.

Figure 83 presents the hardness profile in

an induction surface-hardened layer to a depth

of 5.0 mm and the microhardness profile to

a depth of 150 mm on bearing location “A”

(Ref 44).

The hardness measurements show that the

quenched and tempered steel has a hardness of

approximately 220 to 260 HV

2.0

, and the sur-

face-hardened layer has a hardness of approxi-

mately 540 HV

2.0

. In the surface-hardened

layer, a slight increase in hardness as a function

of depth is evident, which is conditioned by

microstructural differences due to varied cool-

ing rates of the surface layer. The surface is

cooled under the effects imposed by the cooling

medium, yet at a greater depth, the effects of the

medium are accompanied by a more expressed

effect of the cold mass of the core, resulting in

the formation of very fine martensite and greater

hardness at greater depth (Ref 64).

Fig. 83

Hardness profile in the induction surface-hardened layer and microhardness profile in a very thin surface layer for bearing

location “A”. Source: Ref 44

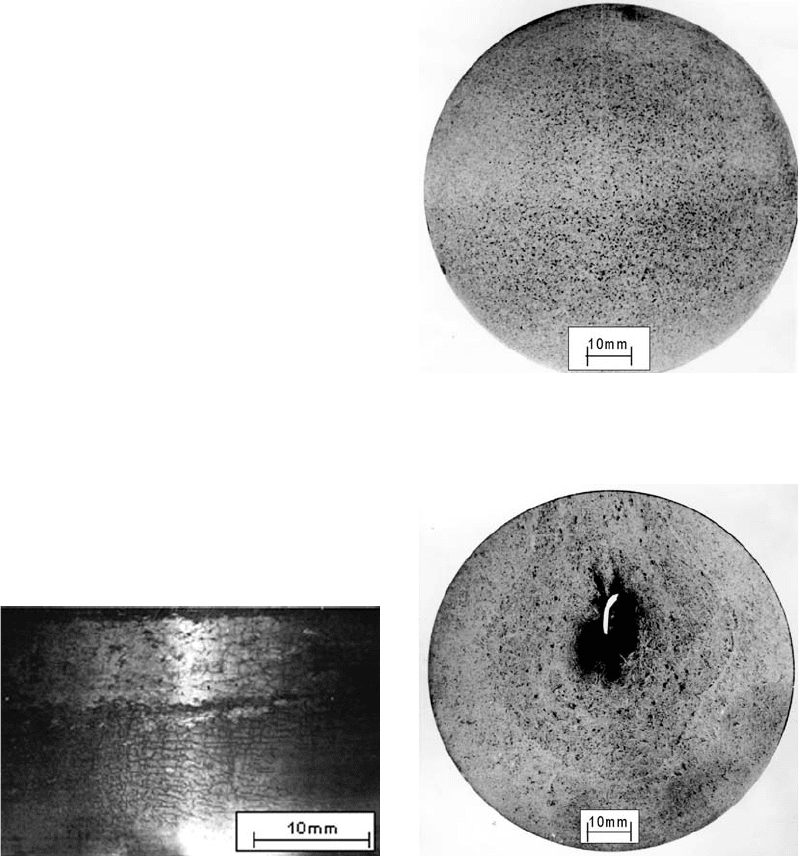

Fig. 84

Hardness profile in the induction surface-hardened layer and microhardness profile in a very thin surface layer for bearing

location “C”. Source: Ref 44

478 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 478

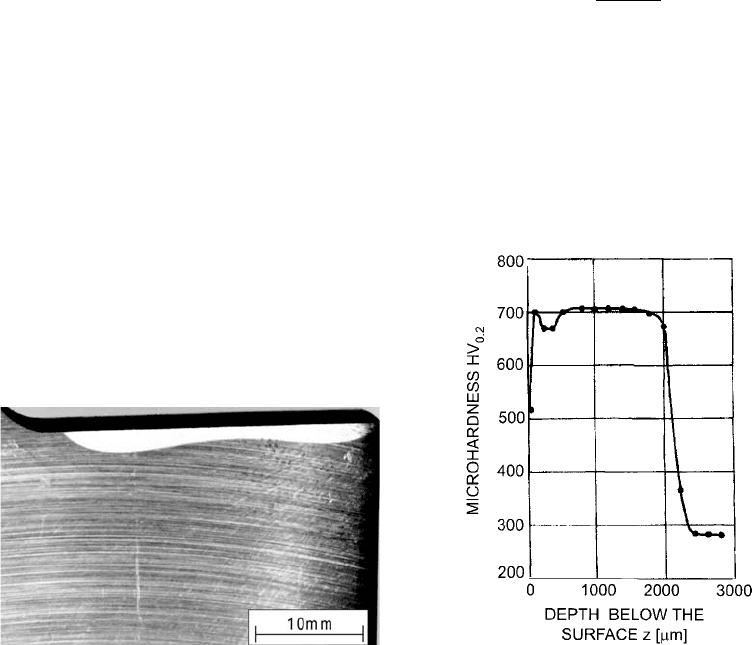

Kosel and Kosec (Ref 67) conducted an

investigation on the cracks formed at the

surface-hardened and ground bearing location

of a crankshaft. Crankshafts are made of high-

quality chromium-molybdenum heat treatable

steel. The shafts were forged from square shafts

with a cross-sectional area of 120 by 140 mm. In

the course of mechanical and heat treatments,

the workpieces were tested with various non-

destructive methods, for example, visual

inspection, and, if required, magnetic particle

and/or penetrant inspections. A peculiarity of

shaft production is that during forging, the

material flows from the middle of a slab ingot to

the outer section of a forging due to plastic

deformation. The steel in the middle is usually of

lower quality than the steel at the surface of a

cast iron-works blank and that of a formed steel-

works semiproduct. The character of forming

the steel-works semiproduct tool, steel-works

blank, and crankshaft was such that a reverse

material flow occurred from the middle to the

surface. The authors reported the presence of

weblike cracks at the surface of the crankshaft

bearing location (Fig. 85) and gave two reasons

for the occurrence of cracks immediately after

forging (Ref 67):

Inhomogeneity, that is, nonuniform cross-

sectional chemical composition of steel

Inadequate conditions of bearing-location

grinding

After macrostructural and microstructural

examinations as well as a microchemical ana-

lysis were performed, it was found that, from the

metallurgical point of view, the forging showed

quality, and the defect may be attributed to the

grinding process alone. Figure 86 shows a

macrosection of the forging at the bearing, and

Fig. 87 shows a forging made of low-quality slab

ingot (Ref 67).

The main purpose of the investigation was to

find the cause of the weblike cracks after

induction surface hardening and the final

grinding on the bearing location on the crank-

shaft. Grinding was studied in the same way as at

the cut-out bearing locations. From the steel-

works slab ingots prepared for forging, speci-

mens of a suitable length were cut out and turned

to size.

Fig. 85

Weblike surface cracks at bearing location of

crankshaft. Source: Ref 67

Fig. 86

Macrograph of etched favorable billet cross section.

Source: Ref 67

Fig. 87

Macrograph of etched unfavorable billet cross

section. Source: Ref 67

Induction Hardening / 479

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 479

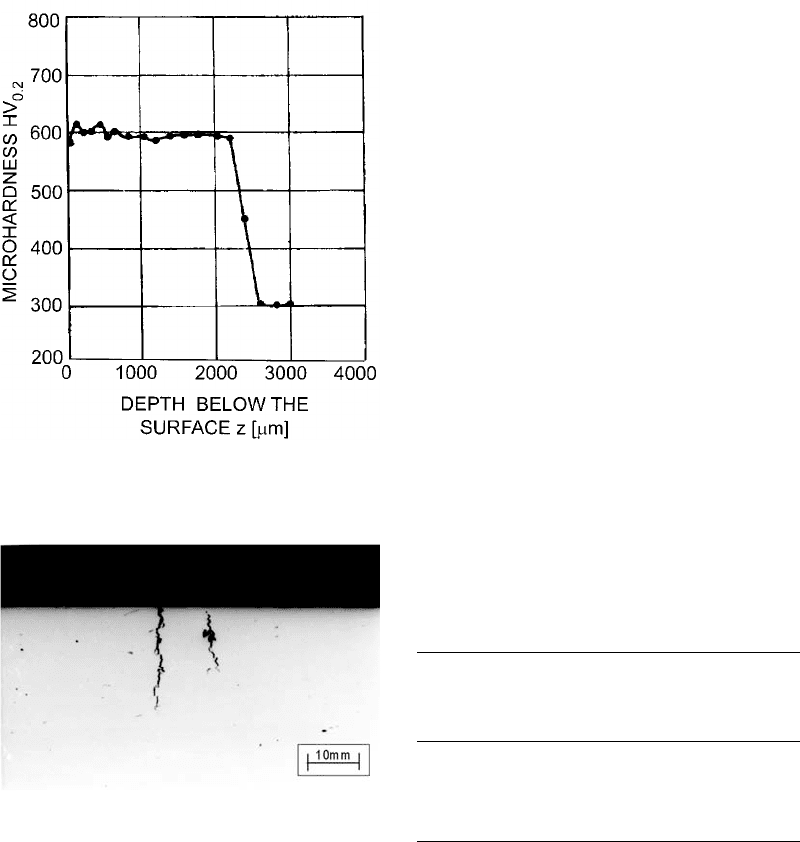

The specimens prepared in this way were

hardened and tempered at 560

C and then sur-

face hardened, with a maximum surface tem-

perature ranging between 820 and 900

C. The

case depth ranged between 3 and 4 mm.

The macrograph in Fig. 88 clearly identifies

the bearing location and shows a considerable

difference in case depth. Generally, it was found

that:

There were insignificant differences in che-

mical compositions.

There were segregations in the central part of

the crankshaft.

There were shrinkage cavities mainly on the

inside and also on the outside part of the

forging.

There were microsegregations.

Some of the hardened bearing locations

showed dimensional variations with refer-

ence to the anticipated thickness.

The microhardness obtained at the surface

was within the expectations and somewhat

above a value of 700 HV

2.0

.

The depth of the hardened bearing locations

ranged between 2.0 and 2.5 mm.

No differences in the microstructures could

be found using a common optical micro-

scope analysis or a scanning electron micro-

scope.

The microhardness at the cracked cylindrical

specimens was somewhat lower, approxi-

mately 600 HV

2.0

.

Figure 89 shows the microhardness profile

of the cross section of an induction-hardened

layer for a favorable bearing location, and

Fig. 90 shows the profile for an unfavorable

bearing location without cracks (Ref 67).

Figure 91 shows two temperature cracks, with

a pore at the crack location being visible as well.

An analytical model was elaborated to clearly

demonstrate the causes of crack formation at the

hardened surface after grinding (Ref 67).

The stress condition, s

R

, occurring at the

hardened-layer surface after heat treatment and

grinding was known. In several cases, the sur-

face-hardened layers took the shape of an

eccentric ring, which means a nonuniform thick-

ness of the hardened layer. The cracks occurred

at the location of the smallest layer thickness. As

expected, residual stress occurs at the specimen

surface where cracks initiate when stress oc-

curs due to phase transformation to martensite,

thermal stresses during hardening, stresses due

to martensitic tempering during grinding, and

thermal stress after grinding (Ref 67).

In the phase transformation from austenite to

martensite, steel volume will increase. The vol-

ume strain can be calculated using the equation:

e

V

=

V

M

7V

A

V

A

where V

M

is the volume of an elementary cell of

martensite, which can be calculated for the given

steel:

V

M

=(2:861 0:013% C)

2

(2:861+0:116% C)

=23:7262 10

3

nm

3

Fig. 88

Macroscopic examination of case depth at cross

section of crankshaft bearing. Source: Ref 67

Fig. 89

Hardness characteristic at cross section of weblike

cracked neck as a function of depth, z. Source: Ref 67

480 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 480

and V

A

is the volume of an elementary cell of

austenite of the same steel:

V

A

=0:5(3:548+0:044% C)

3

=22:68242 10

3

nm

3

then e

V

= 0.046.

A stress condition with such a volume strain

would exceed the material strength. Table 3

indicates that the smallest hardened-layer thick-

ness required is obtained under the condition

that the resulting stress shall be higher than the

breaking stress, according to Hook’s model, and

no cracks occur at the workpiece surface after

grinding (z

min

= 2.873 mm) (Ref 67).

Using the proposed analytical model, the

researchers (Ref 67) evaluated the magnitude of

stresses in steel after surface hardening and

grinding. They found a mutual dependence of

the hardened-layer profile and the resistance

against material cracking during grinding.

Cracks will appear at the surface of those

bearings in which short overheating of steel

occurred and the hardness in a narrow zone

decreased strongly during grinding. In such

cases, through hardenability of a material

reaches a depth of 150 mm, where tempered

martensite will form. The thickness of the

surface-hardened layer with all the cracked

bearings was approximately 2.0 mm, which

indicated that an appropriate model was chosen.

Fatigue Strength of Materials

A heat treatable AISI 4140 steel was used

for manufacturing crankshafts. This steel is

very appropriate for statically and dynamically

loaded parts of car engines and machines

because of its high hardness achieved after hard-

ening (57 HRC). The steel is characterized by

good hardenability and is thus suitable for manu-

facturing machine parts with large cross sections

in which a very high strength can be obtained

after refinement. After tempering, the steel does

not show a tendency to brittleness, and therefore,

no special heat treatment procedures are re-

quired. This steel is also suitable for surface

hardening (flame surface hardening, induction

surface hardening) and displays a very good

resistance to wear.

However, special attention must be paid to the

part design phase, and great care should be given

to the design of radius and transition areas

to prevent notch effects under dynamic loads.

The steel is adapted for use in a wide range of

Fig. 91

Thermal cracks in surface-hardened neck section.

Source: Ref 67

Table 3 Minimum case depth required for no

cracks at workpiece surface

Excentricity

of hardened

layer

(e), mm

Depth

(z), mm

Temperature

prior to

quenching

used in

Hook’s model

(T

K

), °C

Yield

stress of

martensite

R

K

0:2,(T

K

)

,

N/mm

2

Resultant

stress after

hardening

and grinding

(s

R

(T

0

)),

N/mm

2

0.594 3.156 343 1123 1306

0.709 3.0412 336 1144 1327

0.877 2.873 325 1177 1360

1.146 2.6045 307 1232 1414

Source: Ref 67

Fig. 90

Hardness characteristic of neck cross section without

cracks as a function of depth, z. Source: Ref 67

Induction Hardening / 481

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 481

temperatures, and it preserves high toughness

even at low temperatures (Ref 44, 68, 69).

Impact tests provide useful quantitative com-

parative data with relatively simple test speci-

mens and equipment. However, these tests do

not provide property data for design purposes for

material sections containing cracks or defects.

Data of this type are obtained from fracture

mechanics, in which theoretical and/or experi-

mental ways determine the fracture of structural

materials containing pre-existing cracks and

defects.

The number of cycles to failure (N) obtained

by the S-N curve under load or a stress-control

condition is related to the total life of the part up

to failure. Fatigue cycles throughout the life of

the machine part consist of crack initiation and

its propagation. Crack propagation refers to

stable crack growth up to the crack instability.

The S-N curve approach does not separate the

crack initiation phase from propagation. Indus-

trial experts assume that the crack has already

initiated in the machine part, and only the total

number of cycles associated with the propaga-

tion are of interest. Existing or initiated cracks

assumed in the machine part are the result of

dynamic load cycles induced during manu-

facturing, prior to its use. The size of the pre-

existing crack can be assumed based on the

capability of suitable inspection. The expert may

assume an initial surface crack after testing and

makes a decision about the application of the

part.

Using the available initial defects in the

material, the total life of the part can be assessed

by an appropriate fracture mechanics method.

Basic factors affecting the shape of the S-N

curve are:

Materials selection and heat treating or cold

working conditions

Various types of loading on the specimen,

such as tension, compression, torsion, or a

combination

Loading conditions described by medium

stress, amplitude stress, and frequency

Influences on the environment carried by

temperature, corrosion, and other factors

Some major factors that affect the strength of

a metal include:

Stress concentration: Fatigue strength is

greatly reduced by the presence of stress

raisers, such as notches, holes, keyways, or

sharp changes in cross sections.

Surface roughness: In general, the smoother

the surface finish on the metal sample, the

higher the fatigue strength.

Surface condition: Since most fatigue fail-

ures originate at the metal surface, any major

change in the surface condition will affect

the fatigue strength of the metal.

Environment: If a corrosive environment is

present during the cyclic stress of a metal,

the chemical attack greatly accelerates the

rate at which fatigue cracks propagate.

During machining processes, various defects

occur on the surface, such as small scratches and

grooves, and are introduced into the workpiece

surface. Typical failures are moving machine

parts, such as shafts, connecting rods, and gears.

It is estimated that failures of machine parts in

machines contribute approximately 80% of

fatigue failures. These surface detects can limit

the fatigue life. Improving the surface finish by

polishing will increase fatigue life significantly.

One of the most effective methods of in-

creasing fatigue life is the existence of residual

compressive stresses in a thin surface layer.

Thus, applied surface tensile stress will be par-

tially reduced in magnitude by the residual

compressive stress. The net effect is the prob-

ability of crack formation and a consequent re-

duction in fatigue failure.

According to the AISI standard, the heat

treatable structural steel 4140 contains between

0.38 and 0.45% C, 0.90 and 1.2% Cr, and 0.15

and 0.30% Mo. It has very high hardenability,

contributing to high strength values in products

with high mass. Molybdenum yields a desirable

fine microstructure after hot working as well as

heat treatment, contributing to a good strength-

to-toughness ratio. Due to its fine-grained

microstructure, it also reaches a relatively high

toughness in the heat treated condition.

The strength of the steel as well as its sur-

face hardness and wear resistance may be in-

creased by heat treatment and thermochemical

treatment.

Mechanical properties of steel having a dia-

meter of up to 40 mm and between 40 to

100 mm are given in Table 4.

Tensile strength of the steel varies between

880 and 1080 N/mm

2

, and a minimum tough-

ness value, r

3

, equals approximately 41 J. The

steel is very sensitive to notch and transition

on machine parts subjected to fatigue loading.

Fatigue strength of the material is lowest under

torsional load, s

T

, and varies for the diameters

482 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 482

mentioned, that is, 16 to 40 mm, so that

s

T

= 285 N/mm

2

, and for diameters from 40 to

100 mm, s

T

= 255 N/mm

2

. Fatigue strength

under torsional load is three or four times lower

than the tensile strength of steel under static

load, according to the data in the table.

In professional literature, data on fatigue

strength of materials are usually presented for a

prescribed specimen shape and size that has

been adjusted to the testing device. Specimens

for fatigue strength are usually of cylindrical

shape, with a smaller diameter in the middle part

and a rounded transition into the larger-diameter

part. The latter is then usually clamped for

testing. Modes of loading the specimens vary but

are usually either torsion, bending, or tension/

compression. The highest fatigue strength is

displayed by a specimen subjected to bending

loads (Ref 27, 36). For other modes of loading,

the relation with bending fatigue strength, s

wb

,

is expressed empirically, that is, fatigue strength

in torsion, tw, is 0.58 s

wb

, or fatigue strength in

tension/compression, s

wz

, is 0.70 s

wb

.

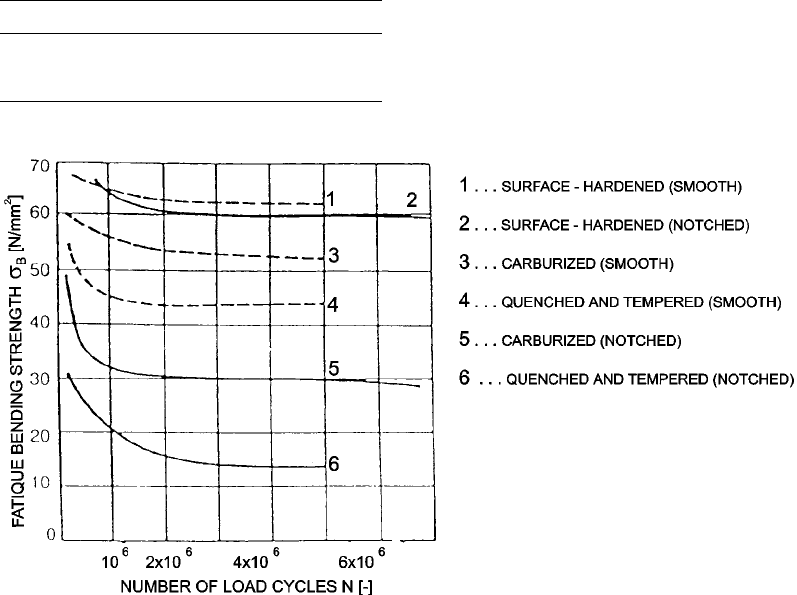

Figure 92 presents curves for different modes

of dynamically loaded specimens made from

various steels that had been heat treated in

assorted ways (Ref 15). From among six curves,

four represent specimens made from heat trea-

table steel and two for cementation steel speci-

mens. The heat treatable steel is Cr-Mo-Ni steel

with 0.37% Ni, and the specimens were heat

treated in two different ways:

Surface hardening applied to specimens with

a smooth shape (curve 1) and specimens

with a slot (curve 2)

Quenching or tempering applied to smooth

specimens (curve 4) and specimens with a

slot (curve 6)

The cementation steel is a chromium-nickel

steel with 0.15% C, where the specimens were

smoothly shaped (curve 3) and slotted (curve 5).

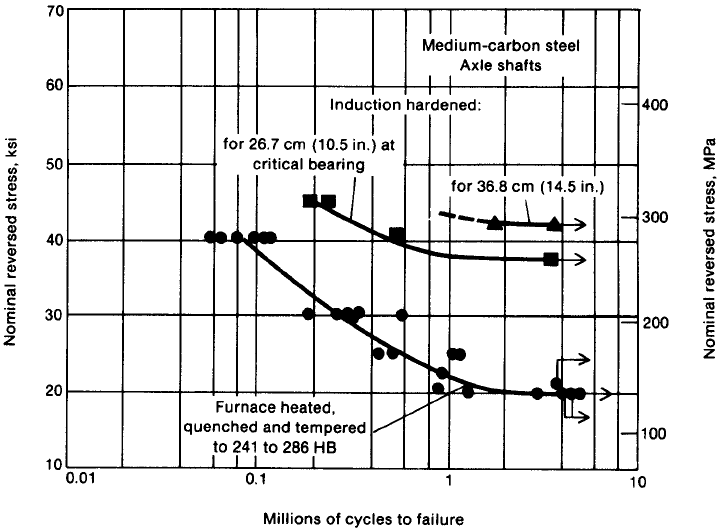

Axle shafts used in cars, trucks, and farm

vehicles are, with few exceptions, surface hard-

ened by induction. Although a portion of the

hardened surface is used as a bearing in some

axles, the primary purpose of induction hard-

ening is to put the surface under a state of com-

pressive residual stress (Ref 45). By this means,

the bending and torsional fatigue life of an axle

may be increased by as much as 200% over that

for parts conventionally heat treated (Fig. 93)

(Ref 45).

Table 4 Mechanical properties of heat treated

structural steel 4140

Diameter

(D), mm

Tensile strength

(R

m

), N/mm

2

Yield point

(R

p0.2

), N/mm

2

Extension

(A

5

), %

Toughness

(r

3

), J

16–540 980–1180 769 11 41

40–5100 880–1080 635 12 41

Source: Ref 15

Fig. 92 Graphs of the fatigue strength of surface-hardened and carburized specimens. Source: Ref 15

Induction Hardening / 483

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 483

Induction-hardened axles consist of a hard

surface, high-strength core, and tough outer case

with good torsional strength and a tough, ductile

core. Many axles also have a region in which the

case depth is kept very shallow, so that the part

can be readily straightened following heat

treatment. In addition to substantially improving

strength, induction hardening is also very cost-

effective. This is because most shafts are made

of inexpensive, unalloyed medium-carbon steel

that is surface hardened to case depths of 2.5 to

8 mm, depending on the cross-sectional size. As

with crankshafts, typical hardness (after tem-

pering) is approximately 50 HRC. Such hard,

deep cases improve yield strength considerably

as well (Ref 45).

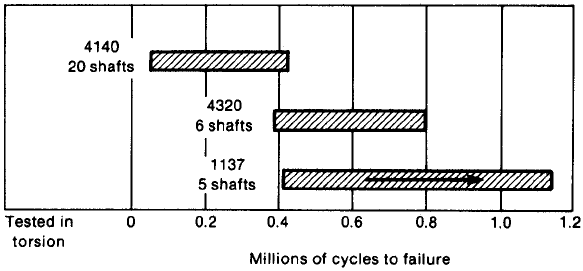

Modern transmission shafts, particularly

those for cars with automatic transmissions, are

required to have excellent bending and torsional

strength, as well as surface hardness for wear

resistance. Under well-controlled conditions,

induction-hardening processes are able to satisfy

these needs, as shown by the data in Fig. 94,

which compares the fatigue resistance of

through-hardened axles (Ref 45). The induction-

hardening methods employed are varied and

include both single-shot and scanning techni-

ques.

The hardness achieved on the surface of the

hardened specimens was 56 to 59 HRC and on

the cemented specimens, 58 to 59 HRC. To test

the effects of the slot on fatigue strength, a slot

of equal size and shape was made on all the

specimens, whether they were quenched or

tempered, hardened or cemented. It was made

in the middle of the cylindrical specimen to an

equal depth of 0.4 mm. The depth on the sur-

face-hardened and cementation specimens was

1.5 mm. The results of testing showed that there

are significant differences in terms of heat

treatment methods and that the highest fatigue

strength was found in surface-hardened speci-

mens.

A comparison of the fatigue testing results

showed that:

In surface-hardened specimens with a

smooth cylindrical shape and with a slot, the

difference in the achieved fatigue strength is

minimal. This can be attributed to a very de-

sirable distribution and size of compressive

residual stresses throughout the hardened

Fig. 93

Bending fatigue response of furnace-hardened and induction-hardened medium-carbon steel tractor axles. Shaft diameter:

70 mm. Fillet radius: 1.6 mm. Source: Ref 45

484 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 484

layer. Since the depth of the slot reaches only

one-quarter of the hardened surface layer,

the size of compressive residual stresses at

the slot is still very high, so that the weak-

ening due to the slot and stress concentration

along the slot does not cause any essential

drop in fatigue strength.

In quenched and tempered specimens with

no earlier prestressing of the surface layer,

the fatigue strength was considerably lower

than in surface-hardened specimens. The

fatigue strength of quenched and tempered

specimens with a slot was also remarkably

lower. The results show that the difference in

fatigue strength in slotted induction surface-

hardened specimens and slotted quenched

and tempered specimens is 5 to 1.

Smooth cemented specimens displayed 25%

lower fatigue strength than the surface-

hardened specimens of the same shape,

whereas the cemented specimens with a slot

displayed 50% lower fatigue strength than

the same surface-hardened specimens.

The question arises about what the fatigue

strength is in those specimens where the slot

reaches deeper than the hardened layer. A

regular problem in these cases is crack

occurrence and propagation of cracks start-

ing from the slot. Due to the shape of the

specimen and the slot, stresses start con-

centrating at these places, depending on the

type and size of external loads. It should not

be forgotten that there are no compressive

residual stresses along the slot, and the size

of tensile stresses along the slot plays a

decisive role in crack occurrence.

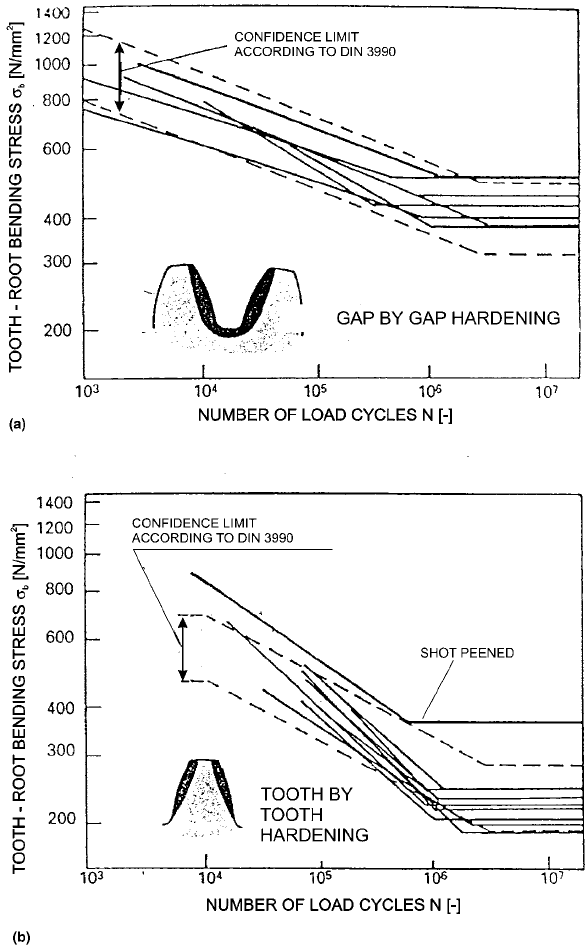

Figure 95 shows bending stress in a tooth root

subjected to dynamic load versus the number of

oscillations (Ref 36). Figure 95(a) shows the

bending stress for induction surface hardening

of adjacent flanks of two teeth with a coil

reaching into the tooth gap. In the process, the

tooth flank as well as the tooth root are hardened

(Ref 36). This kind of heat treatment of gears

from steels for induction surface hardening

provides a fatigue bending strength in the range

of 320 to 490 N/mm

2

. Figure 95(b) shows the

same relationship when the induction coil

encircles an individual gear tooth. In this pro-

cess, the tooth flank is hardened, and the micro-

structure and hardness in the tooth root are

preserved (Ref 36). A result of this method of

hardening is that the fatigue strength is drasti-

cally lowered to values ranging from 200 to

300 N/mm

2

for the entire range of steels suitable

for induction surface hardening. This is a con-

siderable drop in fatigue strength for the material

in the tooth root (Ref 45, 70).

Stress Profiles in Machine Parts in the

Loaded State

Heat treatment engineers must be very careful

in choosing the conditions of induction surface

hardening in order to benefit from the distribu-

tion of residual stresses achieved in dynamically

loaded parts. In industrial practice, induction

surface hardening should satisfy the requirement

of fatigue resistance of machine components.

The main reason for this worsening of the

properties of the machine part is attributed to

tensile residual stresses in the hardened layer

and undesirable hardness distribution in the

transition zone from the hardened into the

unhardened part of the subsurface. These effects

Fig. 94

Comparison of fatigue life of induction surface-hardened transmission shafts with that of through-hardened and carburiz ed

shafts. Arrow in lower bar (induction-hardened shafts) indicates that one shaft had not failed after testing for the maximum

number of cycles shown. Source: Ref 45

Induction Hardening / 485

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 485

are quite natural, and in the first phase are a

result of very rapid local heating of the thin

surface layer, while in the second phase this is

accompanied by forced quenching, which

ensures a critical cooling rate and the occurrence

of a martensitic microstructure. Both phases in

induction surface hardening can increase the risk

of fatigue, especially if the latter is assessed only

from the point of view of surface hardness. To

successfully estimate the quality of the hardened

layer, one must select the optimal synergetic

effects between the input electric energy and the

interdependence between the induction coil and

the workpiece surface, connected with the

Fig. 95

Bending fatigue strength of gear teeth at (a) tooth gap hardening and (b) flank hardening for various steels. Broken lines denote

confidence limit according to DIN 3990. Source: Ref 36

486 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 486

occurrence of eddy currents in the workpiece

surface layer that leads to heating. Due to com-

plex synergetic effects in induction heating

or hardening, it is necessary to carefully study

each influence on the properties of the hardened

surface layer (Ref 27, 45). Fatigue strength

in machine components that have been induction

surface hardened is increased if the total sum

of the load tensions and residual stresses in

the surface layer is of a compressive nature.

To ensure the highest fatigue strength of a com-

ponent, it is necessary to provide the follow-

ing:

In dynamically loaded components, the

surface is prone to fatigue occurrence, so the

surface must have the highest compressive

stresses.

If the total sum of stresses, that is, load ten-

sion plus residual stresses on the surface, is

always of a compressive nature, then there is

no chance for the occurrence of cracks and

crack growth.

To ensure good behavior of the surface and

the hardened surface layer in the loaded

condition, it is necessary to induce a suitable

prestressing in the surface layer. This can be

achieved by a carefully selected heat treat-

ment method that would create the highest

compressive residual stresses on the surface

and a desirable profile of the latter in the

hardened subsurface layer.

Induction surface hardening offers opportu-

nities to ensure a considerable amount of

compressive stresses in the machine com-

ponent surface and to ensure restrained

transformation of compressive surface

stresses into tensile residual stresses in the

subsurface layer.

The endurance of machine components sub-

jected to bending and torsion loads can be suc-

cessfully increased by ensuring sufficiently high

compressive residual stresses. A manufacturing

goal is to create a sufficient amount of com-

pressive residual stresses with a favorable dis-

tribution, since this is the only way to increase

the reliability of components in operation. An

early failure of a component in operation may

cause catastrophic damage on a machine and

thus a loss in profit. A decisive role in the oc-

currence of residual stresses is played by the

synergetic effects between the heat treatment

method, the type of material, and the shape of the

workpiece. For this reason, heat treatment must

be treated from the point of view of heating,

overheating, and cooling/quenching as well as

the internal stresses created at a certain point

during the treatment. During heat treatment,

internal stresses are created by the temperature

differences and phase transformations between

the core and the surface, which are a result of the

volume differences between the core and the

surface. The created volume differences

between the core and the surface then give rise to

internal stresses. During the process of heating

and cooling, internal stresses may produce the

following effects:

When internal stresses are lower than that of

the yield point, higher residual stresses are

induced by heat treatment in the workpiece,

but these would not cause distortions,

cracks, or failure.

During a certain moment in heat treatment,

internal stresses exceed the yield point,

which leads to distortions and lower residual

stresses in the workpiece.

During very detrimental conditions in heat

treatment, internal stresses are higher than

the tensile strength of the material, causing

the workpiece to crack and creating larger

distortions and high residual stresses.

Numerous changes that take place in the

hardened surface layer of the workpiece are

always a result of the heating and quenching

conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to study the

events taking place in the workpiece directly

after the hardening temperature is reached.

Three zones are distinguishable in a workpiece

heated to the hardening temperature (Fig. 96a):

the first zone, where the outer layer is heated to

the hardening temperature; the second zone,

which is heated below the hardening tempera-

ture between the temperatures T

A

1

and T

A

3

for

rapid heating; and the third zone, where the

temperature is lower than T

A

1

(Ref 15).

Heating to the hardening temperature at a

certain depth is followed by quenching. Quen-

ching results in the occurrence of compressive

residual stresses (Fig. 96b), when the familiar

transformations in the hardened layer take place.

The second layer does not suffer the same dis-

tortions as the surface layer, although the heat-

ing there has been sufficient enough to improve

the properties of the material. In the second

layer, hardening is incomplete, which, in com-

parison with the first layer, results in lower

hardness and strength of the material.

Induction Hardening / 487

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_417-501.pdf/Chap_13/ 18/8/2008 4:03PM Plate # 0 pg 487