Canale L.C.F., Mesquita R.A., Totten G.E. Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

factor given by:

c=c

n

=exp(As

ys

1=2

Bs

ys

)

A={2(1+n)V=3RT}{2E=p}

1=2

B={2(1+n)V=RT}{2=p}

where c is the hydrogen concentration at the

crack tip, c

n

is the hydrogen concentration in the

bulk steel, n is Poisson’s ratio, V is the partial

molar volume of hydrogen in iron, E is the

elastic modulus, and s

ys

is the yield strength.

For a high-yield-strength steel having s

ys

=

1000 MPa, the solubility of hydrogen in steel

increases by a c/c

n

factor of 6.5. The tip of a

crack is an excellent site for hydrogen accumu-

lation, because the strain is greater than that

associated with s

ys

.

Although the mechanism for HAC is still

debated, equations to prevent HAC have been

developed empirically. For example, the preheat

parameter (P

w

) and the hydrogen accumulation

parameter (P

HA

), were developed from experi-

mental work in Japan by Yurioka et al. (Ref 15,

41) as practical tools to empirically predict a

preheating temperature to prevent HAC:

P

w

=P

cm

+H

D

=60+R=40,000

where P

cm

is the Ito-Bessyo (Ref 42) carbon

equivalent given as:

P

cm

= C+Si=30+(Mn+Cu+Cr)=20+Ni=60

+Mo=15+V=10+5B

where H

D

is the diffusible hydrogen content

in mL/100 g, elements are in weight percent,

and R is the restraint intensity in MPa. The HAC

can be avoided if the value of P

w

50.3. In the

P

w

equation, the effects of alloy composition,

hydrogen content, and restraint are taken into

account empirically.

Consumables manufacturers have recognized

that filler metals containing less carbon than the

steel plate would produce not only enhanced

weld metal toughness at required strength levels

but also greater resistance to HAC. In fact, vir-

tually all of the older algorithms for determin-

ing preheating temperatures were based on the

composition of the base metal and not the weld

metal. Cracking of the HAZ by HAC was so

common in structural steels that it was assumed

that the coarse-grainced HAZ would always be

the location of maximum susceptibility to

cracking. Using the advantages of modern low-

carbon steels and consumables, Nippon Steel

(Ref 4) designed a series of commercial low-

carbon steels for line pipes that could be welded

while maintaining high strength and toughness

with equally low-carbon filler metals. These

pipeline steels included the X-65, X-70, and

X-80 grades, which contain very low carbon

(50.03%), high manganese for strength and to

control the bainite transformation, and 0.001%

boron to suppress the proeutectoid ferrite nucle-

ation at austenite grain boundaries. It is desirable

to have a large amount of acicular ferrite in the

weld metal for optimal strength and toughness as

well as good resistance to HAC (Ref 43, 44).

Microconstituents detrimental to weld metal

toughness and possibly increased susceptibility

to HAC include grain-boundary ferrite, mar-

tensite, and side-plate ferrite, because these

structures provide a continuous path for cleav-

age crack propagation.

Types of Hydrogen-Assisted Cracking

Hydrogen-assisted cracking can appear in

four common forms:

Underbead or delayed cracking

Weld metal fisheyes

Ferrite vein cracking

Hydrogen-assisted reduced ductility

As mentioned earlier, the mechanism of HAC

is not clear, but management of hydrogen and

the prevention of HAC are well established.

Preheating the weld area prior to and during

welding provides the most reliable resistance to

HAC. There are many empirically-derived

methods to calculate preheat temperatures to

prevent HAC. All of the various types of HAC

can be avoided by good welding practice. The

forms of HAC are discussed in the following

sections.

Underbead or Delayed Cracking

By far, the most common form of HAC is

underbead or delayed cracking, schematically

illustrated as discontinuity 12g in Fig. 1 and

described in Table 1. Typically, this form of

cracking occurs in the coarse-grained HAZ up to

72 h after the weld has cooled. This is because

the HAZ typically has higher carbon content and

Failure Analysis of Steel Welds / 509

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 509

generally a higher carbon equivalent level than

the weld metal. Even though the source of

hydrogen is virtually always from the welding

consumable, atomic hydrogen rapidly diffuses

to crack nucleation sites in the HAZ. The dif-

fusion of hydrogen explains the time-dependent

nature of HAC, thus the name delayed cracking.

The coarse-grained HAZ is the zone adjacent to

the weld and represents a region that has been

heated to nearly the melting temperature, fol-

lowed by rapid cooling. Because of its higher

carbon content and large austenite grain size, the

coarse-grained HAZ develops a significantly

higher hardness than the weld metal. The HAZ

will transform to martensite upon cooling if the

carbon equivalent is high enough. Since the

harder HAZ is more susceptible to HAC than

either the weld metal or the unaffected base

metal, the cracking in a butt weld is typically

confined to a narrow strip of metal immediately

adjacent to the weld bead. Cracking in fillet

welds occurs at the toe of the weld because that

is the location of highest stress concentration.

Toe cracking is schematically illustrated as

discontinuity 12e in Fig. 1 and described in

Table 1.

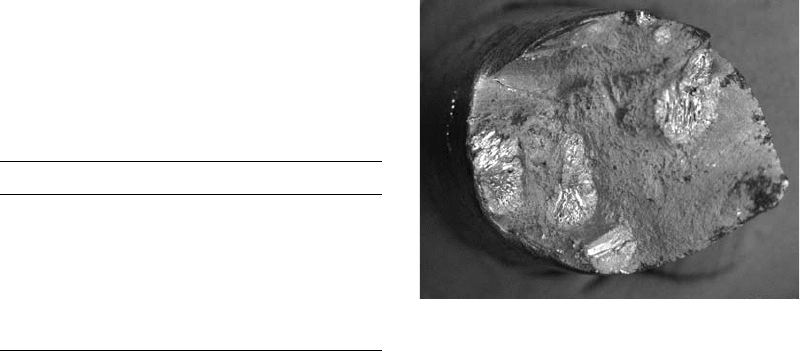

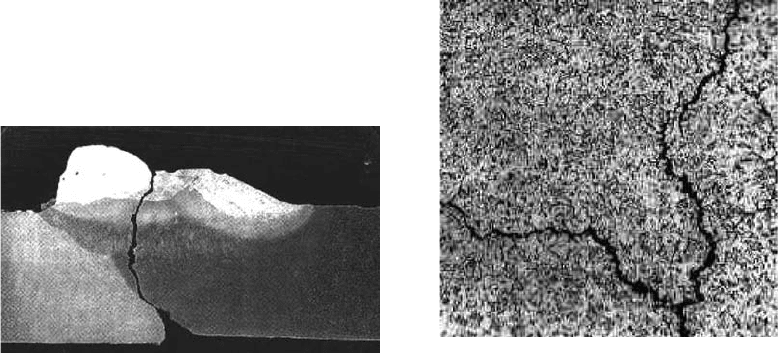

Example 5: Underbead Cracking. Cross-

country line pipe is welded continuously for

long distances. At regular intervals, a flange

needs to be welded onto the pipe for coupling to

a valve or other device. Recently, a section of

pipe was removed from service because of

cracking that had occurred in the toes of the fillet

welds joining the flange to the pipe. The pipe

was 203 mm (8 in.) outside diameter by 6.4 mm

(0.25 in.) wall thickness, and the flange was

205 mm (8.1 in.) inside diameter by 305 mm

(12 in.) outside diameter by 18 mm (0.71 in.)

thick. Since the pipe was only 6.4 mm thick, the

weld was not preheated. Cracks measuring

approximately 10 cm long developed at the toes

of the fillet welds on the flange side, as shown in

Fig. 6.

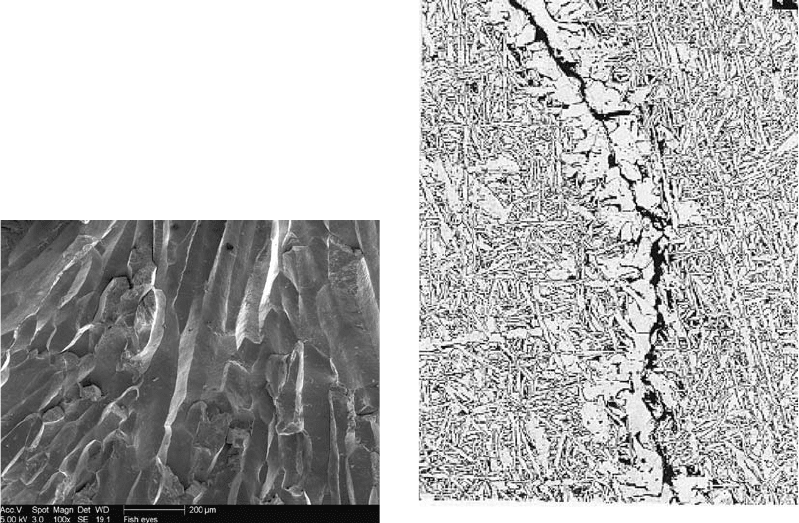

From the illustration in Fig. 6, the cracking

occurred only in the toes of the two fillet welds

on the flange side. No cracking was observed at

the toes of the two fillet welds on the pipe side. A

metallographic section of the crack, shown in

Fig. 7, clearly reveals that the crack was con-

fined to the brittle martensitic HAZ on the flange

side. Scanning electron microscopy of the

cracked area clearly shows an intergranular

mode of fracture (Fig. 8). Chemical analysis of

the pipe and flange in Table 3 revealed that an

incorrect steel was used for the flange. The

Fig. 6

Underbead cracking at the toe of the fillet weld on the

flange

Fig. 7

Toe cracking on the flange side of the flange-to-pipe

fillet weld, showing the weld metal, heat-affected

zone, and unaffected base metal. Cracking occurred in the mar-

tensitic (white) heat-affected zone of the flange.

Fig. 8

Fracture surface of flange failure in the as-received

condition. Intergranular fracture is shown as well as

debris retained from the field.

510 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 510

correct flange steel was supposed to be a low-

carbon steel. Instead, the flange was a 0.8%

(high) carbon steel, which was very susceptible

to HAC in the HAZ when welded without pre-

heating.

Cracking in the HAZ on the flange side of the

fillet weld was due to the mistaken use of a high

0.8% C steel instead of the specified low-carbon

steel. Quality control measures need to be fol-

lowed to prevent mixed steels from being used.

Weld Metal HAC and Fisheyes

Welding of modern low-carbon steels often

results in HAZs with greater resistance to HAC.

Thus, the weld metal composition is now as

susceptible as the HAZ. If the weld metal con-

tains sufficient diffusible hydrogen content, has

high yield strength, and is in a highly stressed

condition, the susceptibility of such weld metal

to HAC is very possible. For example, in

the line-pipe industry, new thermomechanical-

controlled processing steels achieve high yield

strength through thermal processing in the roll-

ing mill, so that the carbon content and carbon

equivalent levels for a given yield strength have

dropped substantially. With this reduction in

carbon equivalent, the susceptibility to HAZ

cracking has also declined significantly. Since

the as-deposited weld metal achieves strength

primarily through alloying, the weld metal is

now very susceptible to HAC. Often, field

welding of X-65 and X-70 line pipe is performed

with high-hydrogen E8010G cellulosic elec-

trodes. In this case, the weld metal yield strength

is greater than both the HAZ and unaffected base

metal. Thus, the weld metal has become the

weak link and is most susceptible to HAC.

The strong influence of hydrogen on weld

metal cracking can be observed in tensile testing

and bend testing as well as in failures of welds

subject to slowly applied tensile stress. Fisheyes

occur typically on the fracture surface of steel

all-weld-metal tensile specimens that fail due to

HAC. In tensile testing, fisheyes reduce the weld

metal ductility measurements, such as percent

elongation and percent reduction of area. Fish-

eyes are local areas within the weld that are more

hardenable due to solute banding, cellular, or

dendritic segregation of alloying elements (Ref

45). These initiation areas may also be richer in

localized hydrogen due to their proximity to

hydrogen traps such as inclusions. Since these

alloy-rich segregated areas are more susceptible

to brittle HAC, small, localized brittle-fracture

zones appear visually on a tensile test fracture

surface as bright round spots surrounded by gray

ductile fracture. The bright round spot may

consist of a local region of typically inter-

granular or possibly cleavage fracture sur-

rounded by ductile dimpled failure. Both

intergranular and cleavage failures are brittle

fracture modes that appear much more brightly

than the surrounding material, which is ductile

dimpled and gray-appearing.

Example 6: Fisheyes on Fracture Sur-

face. A high-strength steel, HSLA-100, was

butt-welded with a matching-strength filler

metal using gas metal arc welding (GMAW) and

argon-5%CO

2

shielding gas at a heat input of

1.1 kJ/mm (28 kJ/in.) without preheating. The

filler metal contained Fe-0.03%C-1.4%Mn-

3%Ni-0.7%Mo. Because of the very low carbon

content, the weld metal hardness did not exceed

24 HRC. Tensile test results showed inadequate

ductility of only 8% elongation.

Upon examining the fracture surface of the

tensile specimen, multiple fisheyes were

observed, as shown in Fig. 9. An SEM image of

Table 3 Chemical analysis of the flange and pipe

Chemical

element Flange Pipe

C 0.80 0.07

Mn 0.67 1.10

Si 0.25 0.24

Ni 0.01 0.01

Cr 0.23 0.01

S 0.13 0.005

P 0.018 0.017

Al ... 0.038

Nb ... 0.02

Fig. 9

Brittle fisheyes appear as bright spots in a gray ductile

matrix.

Failure Analysis of Steel Welds / 511

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 511

the center of a bright fisheye exhibited brittle

intergranular fracture, as shown in Fig. 10. The

SEM images outside of the fisheyes showed

ductile dimpled microvoid coalescence. Welds

were repeated to determine the amount of dif-

fusible hydrogen in similar welds in accordance

with AWS A4.3 (a standard welding test for

diffusible hydrogen). Despite the fact that

GMAW is known as a very low-hydrogen pro-

cess, the value obtained for diffusible hydrogen

was 9 mL/100 g, which was far greater than

expected. It was found that the filler metal

manufacturer used excess hydrocarbon-base

lubricant during the wire-drawing operation

because of the high strength of the wire.

Fisheyes were caused by excessive amounts

of diffusible hydrogen in the weld metal due to

the lubricant residue on the filler metal.

Ferrite Vein Cracki ng

A very unexpected form of HAC is ferrite

vein cracking, which can occur in slowly cooled

electroslag welds. In recent studies of electro-

slag welding of 50 and 75 mm thick low-carbon

steel at Portland State University (Ref 46),

ferrite vein cracking of A709-grade 245 steel

occurred only in welds that were made with flux

and/or filler metal known to have high moisture

content. Although the mechanism is not certain,

diffusible hydrogen causes the ferrite at prior-

austenite grain boundaries to crack under the

residual tensile stress produced by contraction

during weld cooling. This is very unusual,

because typical HAC is associated with hard

martensitic microstructures. Ferrite was always

thought to be immune to HAC because of its low

strength and low hardness. It was also found that

nickel alloying additions tended to promote

HAC in the form of ferrite vein cracking, while

an equivalent amount of molybdenum resisted

cracking. Both nickel and molybdenum are

essential alloying elements for enhancing frac-

ture toughness in both the weld metal and base

metal. The mechanism by which nickel and

molybdenum appear to have virtually opposite

effects on susceptibility to HAC is not known.

Example 7: Ferrite Vein Cracking in

High-Heat-Input Welds. Single-pass full-

penetration electroslag welds were deposited on

50 mm (2 in.) thick ASTM A588 steel using a

heat input of 42 kJ/mm (1070 kJ/in.) for bridge

applications. The ASHTO/AWS D1.5 Bridge

Welding Code required both radiographic and

ultrasonic testing (UT) of the completed welds.

The UT revealed possible indications of crack-

ing around the weld center. The weld metal was

sectioned for metallographic examination, and

ferrite vein cracking was found, as shown in

Fig. 11.

Clearly, cracking was confined to the grain-

boundary ferrite, which was nucleated at the

prior-austenitic grain boundaries.

Fig. 10

SEM image of center of fisheye showing intergranular

fracture

Fig. 11

Ferrite vein crack occurring in the prior-austenite

grain boundaries of weld metal deposited on A709-

grade 50W

512 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 512

Review of the welding procedure revealed

that the flux and tubular wire used in this process

were not baked prior to welding. The unbaked

flux was a source of moisture. Despite its ex-

tremely high weld heat input and the use of mild

steel electrodes, electroslag weld metal has been

shown to be susceptible to HAC. The fabricated

metal-cored tubular wire was also unbaked.

Under the welding heat, moisture in the flux

and filler metal produces atomic oxygen and

hydrogen. Since electroslag welds are large

single-pass deposits, the weld center is under

substantial tensile stress. The combination of

ample diffusible hydrogen and high-shrinkage

tensile residual stress at the weld center provides

the necessary ingredients for ferrite vein crack-

ing. Subsequent welds were made with flux that

was baked to 204

C (400

F) and a new metal-

cored wire that was baked at an elevated tem-

perature prior to shipment. The resulting welds

have since been free of ferrite vein cracking.

Although the mechanism of HAC of grain-

boundary ferrite is unknown, elimination of

cracking was achieved by reducing the sources

of moisture or hydrogen.

Hydrogen-Assisted Reduced Ductility

This form of HAC occurs when the damage

due to diffusible hydrogen is not sufficient to

cause cracking in the weldment but is sufficient

to cause reduced ductility in subsequent tensile

and bend tests. This is a clear illustration of the

principles reported by Beachem (Ref 32) and

shown schematically in Fig. 5. All fracture

modes become more severe with increasing

diffusible hydrogen. Even the ductility asso-

ciated with ductile microvoid coalescence is

substantially reduced in the presence of diffu-

sible hydrogen.

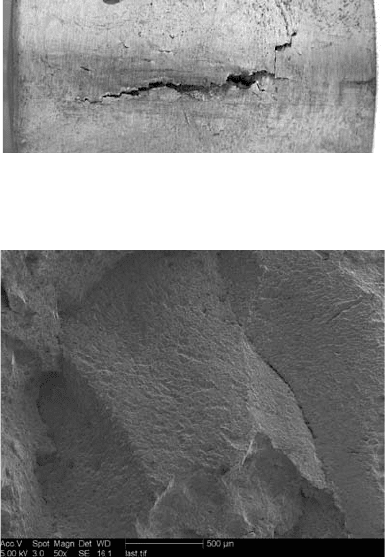

Example 8: Failure to Pass Bend Tests due

to Hydrogen. Multipass submerged arc welds

deposited on 50 mm thick A588 steel were

subject to inspection in accordance with the

AWS D1.1 Structural Welding Code. The fol-

lowing tests were performed for the procedure

qualification welds: tensile testing, bend testing,

Charpy V-notch impact toughness testing, as

well as both ultrasonic and radiographic testing.

All of these tests were passed successfully ex-

cept the guided bend test. As shown in Fig. 12,

the side-bend specimen cracked well before the

prescribed bend radius could be achieved.

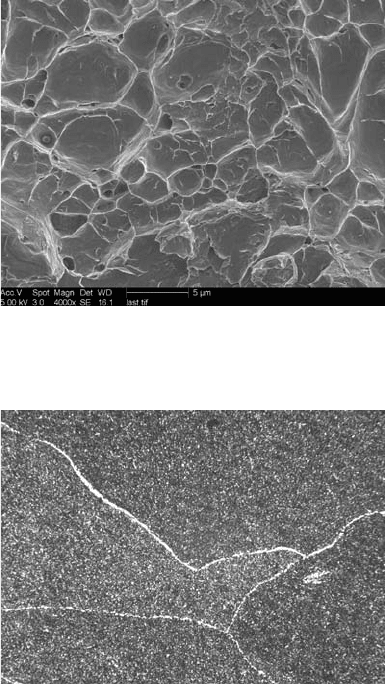

Visual inspection and low-magnification op-

tical microscopy of the cracked bend specimen

exhibited an intergranular mode of fracture.

Scanning electron microscopy at 50 · revealed

that the crack propagated intergranularly along

the prior-austenite grain boundaries, as shown in

Fig. 13. However, at approximately 4000 · , the

intergranular fracture surface exhibited shallow

dimples, as shown in Fig. 14. This dimpled

intergranular mode of fracture is due to the

weakness of the ferrite envelopes surrounding

each prior-austenite grain, as shown in Fig. 15.

The presence of diffusible hydrogen caused a

reduction of ductility of grain-boundary ferrite

sufficient to fail the bend test. The Beachem

diagram in Fig. 5 shows that microvoid coales-

cence can also be adversely affected by diffu-

sible hydrogen. Using low-hydrogen practices,

such as baking the flux prior to use, eliminated

the cracking problem during bend testing.

Stress-Corrosion Cracking of Steel

Stress-corrosion cracking of steels is possible

when the steel is subject to both adequate tensile

Fig. 12 Side-bend test failure of weld

Fig. 13

Scanning electron micrograph of fracture surface of

bend failure

Failure Analysis of Steel Welds / 513

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 513

stress (but below the yield strength) and an

aggressive environment. The absence of one of

these elements will eliminate stress-corrosion

cracking. Welds are particularly good sites for

stress-corrosion cracking, because substantial

tensile residual stresses are always present. The

shrinkage stresses associated with the solidifi-

cation and cooling of welds produce near-yield

tensile residual stresses in and around the weld.

Relatively mild chemical environments can

activate the stress-corrosion cracking process.

Environments known to cause stress-corrosion

cracking of plain carbon and alloy steels include

liquefied ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, molybde-

num disulfide, sodium hydroxide sour gas, high

pH values, nitrate solutions, and many other

corrosive environments. Stress-corrosion crack-

ing of carbon steel can even take place in pure

water under high temperature and pressure.

Although many theories for stress-corrosion

cracking have been suggested, only two appear

to be the basis for such cracking. These are the

stress-sorption theory and the electrochemical

theory.

The stress-sorption theory states that dam-

aging substances in the environment are chemi-

cally absorbed onto the surface of the steel,

causing a reduction in the cohesive bonding

force between iron atoms. Only an atom-thick

surface layer is needed to seriously affect the

bonding forces between surface atoms. There

is a threshold stress necessary to initiate stress-

corrosion cracking. In some ways, this mechan-

ism resembles HAC in steels (discussed earlier),

where only a few ppm of hydrogen in concert

with tensile stress are needed to reduce the

cohesive bonds between iron atoms and cause

cracking. In stress-corrosion studies, acoustic

emission sensors have been attached to the

cracking sample to monitor the propagation of

the crack. Strong acoustic emissions were em-

itted and recorded each time the advancing crack

jumped or burst. Acoustic emission sensors used

to monitor HAC of steel displayed a similar

jump or burst behavior.

The electrochemical theory involves the

setting up of galvanic cells within the micro-

structure of the steel. Anodic dissolution paths

are produced along concentration gradients in

the metal or in grain boundaries. When the grain

boundaries are anodic to the bulk of the metal,

tensile stresses (although below yield) are

necessary to continue the cracking process in

order to open up dissolved pathways for further

penetration by the corrosive environment. As

evidence of the electrochemical nature of this

cracking process, stress-corrosion cracking can

be stopped by applying cathodic protection. As

soon as cathodic protection is removed, stress-

corrosion cracking continues.

Example 9: Stress-Corrosion Cracking of a

Weld. After 30 years in service, a low-pressure

steam supply line developed a reoccurring

cracking problem in a circumferential butt weld.

The weld was on a 25 cm (10 in.) supply line

that carried 0.4 MPa (55 psig), 205

C (400

F)

steam to a paper machine. This line was 30 m

(100 ft) downstream from a spray attemperator

that cooled higher-temperature steam by spray-

ing boiler feedwater into the line.

When cracks were initially discovered, they

were ground out and rewelded. The repair welds

reportedly cracked after only a few days in

service.

Fig. 14

Higher-magnification image of fracture surface in

Fig. 13 showing dimpled intergranular fracture

Fig. 15

Optical microscopy of grain structure of electroslag

weld metal. Original magnification: 50 ·

514 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 514

A visual examination revealed that neither the

original welds nor the repair welds penetrated

through to the inside of the pipe. The cracking

consisted primarily of circumferential cracks

down the center of the weld. In addition, there

were a few locations where short longitudinal

cracks emanated from the primary circumfer-

ential crack. Macroscopically, the cracks were

generally irregular and branching.

Sections of the cracked region were prepared

for metallographic examination of the weld

geometry and crack morphology, as shown in

Fig. 16. A microhardness scan of the base metal

revealed a hardness of 79 HRB, with a hardness

of 87 to 94 HRB in the original weld. The repair

weld was significantly harder, with a hardness of

22 to 34 HRC.

Metallographic investigations revealed an

intergranular branching morphology, as shown

in Fig. 17. Scanning electron microscopy also

showed the presence of several secondary

branching cracks emanating from the primary

crack. These cracks also proceeded in an inter-

granular fashion. Energy-dispersive spectro-

scopy did not reveal the presence of foreign

materials at the fracture surface in a measurable

quantity.

The pipe fractured due to stress-corrosion

cracking (SCC) precipitated by the presence of

geometric stress concentrations and high resi-

dual tensile stresses in the weld. The SCC is an

environmentally induced cracking mechanism

that can occur in a susceptible material in the

presence of tensile stress and an aggressive

chemical agent. Although the particular agent in-

volved could not be identified, this is not unusual,

because small amounts of a caustic agent can

often cause cracking in the proper conditions.

Due to the location of the cracking, it is likely

that the agent entered the line in the spray

attemperator process. It is likely that an upset in

the chemistry of the boiler feedwater at some

time in the past contaminated the downstream

lines and led to the SCC in this instance.

The consequences of additional steam line

failures need to be evaluated. Given the nature of

the cracking, inspection methods capable of

detecting the cracks in early stages are limited. It

may be most cost-effective to replace the steam

lines downstream of the attemperator and re-

evaluate the methods used for ensuring the

proper chemistry of the boiler feedwater.

Future repairs should ensure complete crack

removal and full penetration welds using proper

preheat and interpass temperatures to minimize

hardness gradients.

Solidification Cracking of Steel

Solidification cracking is one of several forms

of hot cracking. Solidification cracking in steel

and steel alloys occurs near the end of the soli-

dification process and is caused by two dominant

factors: tensile stress acting on the weld during

solidification, and a large temperature range

between the solidus and liquidus temperatures or

the presence of low-melting impurities such as

sulfer and phosphorus. The tensile stress acting

on the weld can arise from either shrinkage

tensile stresses produced during solidification

and cooldown, or externally applied tensile

stress or tensile restraint stress. The effect of the

liquidus-to-solidus temperature range has been

Fig. 16.

Cross section of weld at butt joint. Etchant: 2% nital.

Courtesy of MEI-Charlton, Inc.

Fig. 17

Micrograph of the crack near the weld root. Original

magnification: 100 · . Etchant: 2% nital. Courtesy of

MEI-Charlton, Inc.

Failure Analysis of Steel Welds / 515

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 515

dealt with generally by several empirical soli-

dification cracking equations. For example,

Matsuda (Ref 47) developed a very popular

parameter for solidification cracking of steels

called L

t

, where increasing L

t

increased sus-

ceptibility to cracking:

L

t

=70(C Si=12 Mn=9+3P+4S+Ni=23

+Cr=35+Mo=70)

where all elements are in weight percent.

Clearly the effects of carbon and alloying

elements such as manganese, molybdenum,

chromium, and nickel were assumed to be linear,

as shown in the L

t

equation. As the L

t

equation

suggests, decreasing carbon content has always

been assumed to decrease solidification cracking

susceptibility in steel weld metal. Prediction

formulas for solidification cracking show

the effect of carbon on cracking to be linear.

However, recent research has shown that the

effect of carbon on solidification cracking of

low-carbon steels is far more complex and

nonlinear than predicted by the L

t

formula.

For example, Masumoto (Ref 48) showed that

solidification cracking was enhanced for carbon

contents 40.1%. Conversely, Ohshita et al. (Ref

41) reported that cracking was enhanced for

carbon 50.1% and that nickel additions were

beneficial in reducing the cracking effect of

carbon, Karjalainen et al. (Ref 49) surveyed the

technical literature and reported that there was a

least-susceptible range of carbon contents

between 0.1 and 0.17%. Within this range, the

cracking susceptibility was minimized. Ichi-

kawa et al. (Ref 50) reported peak solidification

cracking susceptibility at 0.035% C, followed by

enhanced cracking when the carbon content

exceeded 0.1%. Most recently, Kim et al. (Ref

51) and Won et al. (Ref 52) showed a peak

in solidification cracking susceptibility at

approximately 0.10% C. It was apparent from

the literature that the effect of carbon on soli-

dification cracking susceptibility of steel weld

metal required further study.

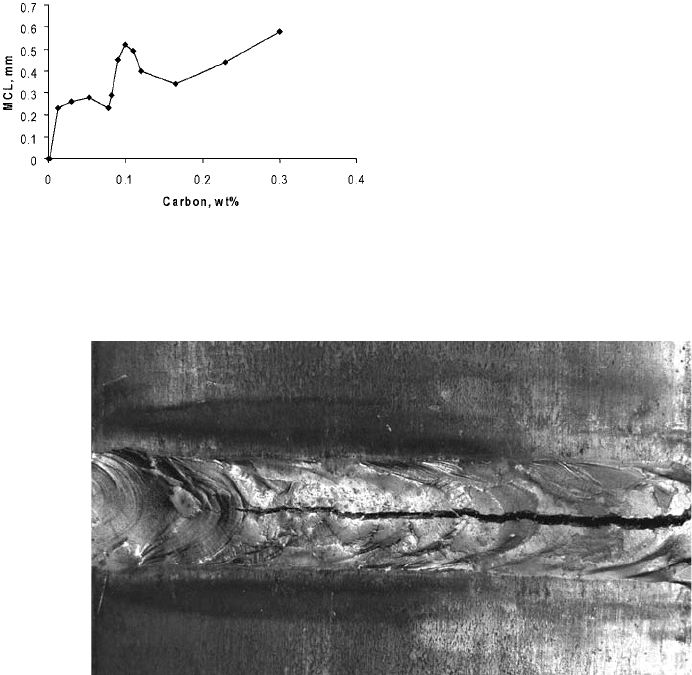

In the most recent work by Shankar and

Devletian (Ref 53, 54), the effect of carbon on

solidification cracking was nonlinear, with a

peak in cracking susceptibility at 0.1% C, as

shown in Fig. 18. In this study, testing was

performed on high-purity iron-carbon alloy

castings using the varestraint and transvar-

estraint tests. Maximum crack distance and

maximum crack length were measured at a 4%

augmented strain.

Fig. 18

Maximum crack length (MCL) as a function of carbon

content in iron weld metal obtained in transvar-

estraint tests at 4% augmented strain. Source: Ref 53, 54

Fig. 19 Solidification cracking in weld metal

516 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 516

The data (schematically plotted in Fig. 18)

clarify some of the conflicting issues in the

literature. Solidification cracking susceptibility

is controlled by the brittle temperature range

(BTR), the d?c transformation stress, and the

iron-carbon peritectic reaction. According to

Shankar and Devletian (Ref 53, 54), there are

four distinct %C ranges that produced char-

acteristic solidification behavior. These include:

Region 1: less than ~0.09% C (maximum

solid solubility of carbon in d-iron)

Region 2: ~0.09 to 0.11% C (maximum

solidification cracking)

Region 3: ~0.11 to 0.16% C

Region 4: greater than 0.16% C (iron-carbon

peritectic point)

In region 1, there was no cracking below

0.01% C in transvarestraint tests. This is because

the solidus/liquidus temperature range was

negligible. However, as the carbon content in-

creased, the cracking susceptibility increased

rapidly up to approximately 0.06% C. The

cracking dropped slightly at 0.075% and then

continued to increase with carbon content up to

0.09%, due to the increasing solidus/liquidus

temperature range. In region 2, a large peak in

solidification cracking was observed. This cri-

tical cracking peak, centered at approximately

0.1% C, was found to be due to the simultaneous

action of three factors: the maximum solidus/

liquidus temperature range, the d?c trans-

formation stresses, and the occurrence of the

BTR. At 0.1% C, cracking occurred with a

minimum critical strain and low fracture stress.

In region 3, solidification cracking decreased

with increasing carbon content because of the

decreasing solidus/liquidus temperature range.

In region 4, the solidification cracking suscept-

ibility increased due to the increasing solidus/

liquidus temperature range.

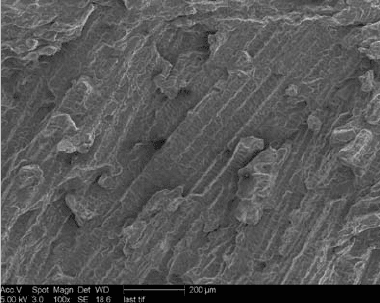

Example 10: Solidification Cracking of

Steel Weld. Welds were deposited by flux-

cored arc welding on 12 mm thick AISI/SAE

1020 steel plate at high travel speeds for maxi-

mum cost-effectiveness. Weld joints were

highly restrained during welding to prevent

distortion. Visible longitudinal centerline cracks

were observed, as shown in Fig. 19. The portions

of the weld seam that were not visibly cracked

failed the root bend test.

The cracked specimen was broken open and

observed under the SEM. Rejected bend-test

specimens were also broken open for examina-

tion by SEM. The crack surface clearly showed

that the mode of fracture was solidification

cracking, as shown in Fig. 20. Spectrographic

analysis of the weld metal admixture revealed a

carbon content of 0.1%. Subsequent welds were

deposited with reduced welding travel speed in

order to reduce the length of the teardrop shape

of the weld puddle. Subsequent welds deposited

at the reduced welding speed were crack-free.

Centerline cracking failure was caused by

solidification cracking. Decreasing welding

speed reduced susceptibility to solidification

cracking in the weld metal. Reducing restraint

during welding and reducing the weld metal

carbon content (or Matsuda’s L

t

factor, men-

tioned previously) would have also decreased

the occurrence of solidification cracking.

REFERENCES

1. AASHTO/AWS D1.5 Bridge Welding

Code, American Welding Society

2. N. Yurioka, M. Okumura, T. Kasuya, and

S. Ohshita, Welding Note, 3rd ed., Nippon

Steel, Japan, 1985

3. N. Yurioka, Weldability of Modern High

Strength Steels, Nippon Steel Corporation,

Japan, 1990

4. K. Shinada, Y. Horrii, and N. Yurioka,

Development of Weld Metal with High

Toughness and Low Har denability, Nippon

Steel Corporation, 1989

5. J.M. Sawhill, J.C. Baker, and P. Howe,

Hydrogen-Assisted Cracking in High

Strength Pipeline Steels, Weld. J., Vol 65

(No. 7), 1986, p 175s–183s

Fig. 20

Scanning electron micrograph of fracture surface

showing solidification cracking

Failure Analysis of Steel Welds / 517

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 517

6. N. Yurioka and T. Kasuya, A Chart Method

to Determine Necessary Preheat in Welding,

Weld. World, Vol 35 (No. 5), 1995, p 31–38

7. N. Yurioka and T. Kasuya, “A Chart

Method to Determine Necessary Preheat in

Welding,” IIW Doc. II-1230-94 and IIW

Doc. IX-1740-94, International Institute of

Welding, 1994, p 12

8. T. Kasuya and N. Yurioka, Determination

of Necessary Preheat Temperature to Avoid

Cold Cracking under Varying Ambient

Temperature, ISIJ Int., Vol 35 (No. 10),

1995, p 1183–1189

9. M. McParlan and B.A. Graville, Hydrogen

Cracking in Weld Metals, Weld. J., Vol 55

(No. 4), 1976, p 95s–102s

10. J. Brozda, A Comparison Between the

Levels of Preheat Necessary to Prevent

Cold Cracking during Welding of Low

Alloy High Strength Steels, Weld. Int.,

Vol 11 (No. 2), 1997, p 25–32

11. B.A. Graville, “Interpretive Report on

Weldability Tests for Hydrogen Cracking of

Higher Strength Steels and their Potential

for Standardization,” Bulletin 400, Welding

Research Council, New York, 1995

12. T. Terasaki, G.T. Hall, and P.L. Harrison,

Predictive Equation for Cooling Time of

CTS Test Welds, Trans. Jpn. Weld. Soc.,

Vol 21 (No. 2), Oct 1990, p 51–55

13. N. Yurioka, H. Suzuki, H. Okumura, S.

Ohshita, and S. Saito, “Carbon Equivalents

to Assess Cold Cracking Sensitivity and

Hardness of Steel Welds,” Nippon Steel

Technical Report 20, Dec 1982, p 61–73

14. F.R. Coe, Welding Steels without Hydrogen

Cracking, The Welding Institute, Abington,

U.K., 1973

15. N. Yurioka, H. Suzuki, S. Ohshita and

S. Saito, Determination of Necessary Pre-

heat Temperature in Steel Welding, Weld.

J., Vol 62 (No. 6), 1983, p 147s–153s

16. C.L.M. Cottrell, An Improved Predictive

Method for Avoiding Hydrogen Cracking,

Weld. Met. Fabr., April 1990, p 178–183

17. N. Yurioka, “Studies on Delayed Cracking

in Steel Welds (Report 1); Prevention

of Root Cracking in Root-Pass Welds,”

Nippon Steel Corporation, Dec 1981

18. N. Yurioka, “Studies on Delayed Cracking

in Steel Welds (Report 2); Prevention of

Cracking in Restraint Multi-Run Welds,”

Nippon Steel Corporation, Dec 1981

19. N. Yurioka, “Studies on Delayed Cracking

in Steel Welds (Report 3); Prevention of

Micro- and Transverse Cracking in Weld

Metals,” Nippon Steel Corporation, Oct

1983

20. R.J. Wong and R.D. Hayes, Arc Welding

Consumables for HSLA Steels with Yield

Strengths of 80 ksi and Above, The Metal-

lurgy of Welding and Qualification of

Microalloyed Steel Weldments, J.T. Hickey

et al., Ed., American Welding Society,

1990, p 450–489

21. P.W. Holsberg and R.J. Wong, Welding of

HSLA-100 Steel for Naval Applications,

Weldability of Materials, R.A. Patterson

and K.W. Mohin, Ed., ASM International,

1990, p 219–239

22. J.J. DeLoach, C. Null, S. Fiore, and

P. Konkol, The Right Welding Wire Could

Help the U.S. Navy Save Millions, Weld. J.,

Vol 78 (No. 6), June 1999, p 55–58

23. R.A. Oriani and P.H. Josephic, Equilibrium

Aspects of Hydrogen-Induced Cracking of

Steels, Acta Metall., Vol 22 (No. 9), 1974,

p 1065–1074

24. R.A. Oriani, Effects of Hydrogen on the

Plastic Response of Steels, Hydrogen

Effects in Metals, I.M. Bernstein and A.W.

Thompson, Ed., Metallurgical Society of

AIME, 1981, p 235–245

25. R.A. Oriani, Hardening and Softening

Induced by Hydrogen in Carbon Steels,

NATO Conf. Series, Mater. Sci., Vol 5,

1983, p 795–798

26. J.K. Lin and R.A. Oriani, Effect of Hydro-

gen on the Initiation of Shear Localization

in Plain Carbon Steels, Perspectives in

Hydrogen in Metals, Pergamon Press, 1986,

p 615–621

27. R.A. Oriani, Hydrogen—The Versatile

Embrittler, Corrosion, Vol 43 (No. 7), July

1987, p 390–397

28. R.A. Oriani, Effects of Hydrogen on the

Plastic Properties of Medium Carbon Steels,

Metall. Trans. A, Vol 11 (No. 11), 1980,

p 1809–1820

29. J.K. Lin and R.A. Oriani, Effect of Hydro-

gen on the Initiation of Shear Localization

in Plain Carbon Steels, Acta Metall., Vol 31

(No. 7), 1983, p 1071–1077

30. H.A. Wriedt and R.A. Oriani, Effect of

Tensile and Compressive Elastic Stress

on Equilibrium Hydrogen Solubility in a

Solid, Acta Metall., Vol 18 (No. 7), 1970,

p 753–760

31. A.R. Troiano, The Role of Hydrogen

and Other Interstitials in the Mechanical

518 / Failure Analysis of Heat Treated Steel Components

Name ///sr-nova/Dclabs_wip/Failure_Analysis/5113_503-519.pdf/Chap_14/ 18/8/2008 4:06PM Plate # 0 pg 518