Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

POISONINGS & INGESTIONS

767

patient has severe serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malig-

nant syndrome. Cyproheptadine and chlorpromazine poten-

tially antagonize serotonin in the CNS, but there are no

controlled trials of these agents. However, chlorpromazine

may be contraindicated in neuroleptic malignant syndrome

because of its antidopaminergic properties. On the other

hand, bromocriptine, a central dopaminergic agonist thought

to be useful in neuroleptic malignant syndrome, may cause

the serotonin syndrome and therefore is contraindicated.

One approach is to treat with benzodiazepines as neces-

sary while carefully supporting the patient and considering

the need for dantrolene and cyproheptadine. When the clin-

ical picture becomes clearer, then other treatment may be

added.

Boyer EW, Shannon M: The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med

2005;352:1112–20. [PMID: 15784664]

Kaufman KR et al: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin

syndrome in the critical care setting: Case analysis. Ann Clin

Psychiatry 2006;18:201–4. [PMID: 16923659]

Rusyniak DE, Sprague JE. Toxin-induced hyperthermic syndromes.

Med Clin North Am 2005;89:1277–96. [PMID: 16227063]

Antihypertensives

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

β-Blockers:

Bradycardia.

Conduction blocks.

Hypotension.

Cardiogenic shock.

Depressed mental status.

Calcium channel blockers:

Bradycardia.

Hypotension.

Heart block.

Drowsiness.

General Considerations

Acute overdose of β-blockers and calcium channel blockers

can be potentially life-threatening and poses significant

treatment challenges for the intensivist. Clinical manifesta-

tions of β-blocker overdose are due to the effects of systemic

β-adrenergic blockade. Toxic effects involve mainly the car-

diovascular system, but CNS effects are seen as well. β-

Blockers are absorbed rapidly from the GI tract, and clinical

effects may appear as rapidly as 20–60 minutes after inges-

tion. Half-life depends on the specific drug but ranges from

2–12 hours; excessive overdose may prolong this half-life.

Clinical effects of calcium channel blocker overdose are

caused by actions on the myocardium and on the smooth

muscle of blood vessels. This produces vasodilation and neg-

ative inotropic, dromotropic, and chronotropic activity. The

most commonly used calcium channel blockers are vera-

pamil, diltiazem, and nifedipine, and each has slightly differ-

ent effects. All are well absorbed from the GI tract, but

diltiazem and verapamil both undergo a significant hepatic

first-pass effect. Metabolism is primarily in the liver.

Clinical Features

Although toxicity is seen most frequently with oral ingestion,

significant β-blocker toxicity also can be seen in patients

being treating with β-blocker eyedrops for conditions such as

glaucoma. Patients with significant β-blockade toxicity pres-

ent with bradycardia, conduction blocks, hypotension,

decreased cardiac output, and cardiogenic shock; depressed

mental status also may be seen. Bradycardia can be severe

and appears to be more common with ingestions of propra-

nolol than with other drugs. Overdose with atenolol, nadolol,

carvedilol, and metoprolol tend to present with hypotension

and a heart rate that may be within normal limits. Pindolol

and practolol overdoses may present with tachycardia owing

to their partial agonist activity. First-degree atrioventricular

block is common with propranolol overdoses, and junctional

rhythms, bundle branch block, complete atrioventricular

block, and asystole all have been observed with β-blocker

ingestions. Hypotension is common and may be profound.

Depressed mental status is also seen frequently and is more

common in patients with significant hypotension. Seizures

are uncommon but do occur with propranolol ingestion.

Significant bronchospasm is surprisingly rare.

Significant calcium channel blocker overdose commonly

presents with bradycardia, hypotension, and significant heart

block (including third-degree heart block), which can be life-

threatening. Hypotension is due to both decreased cardiac

output and peripheral vasodilation. These patients also may

be somewhat drowsy, although markedly altered mental sta-

tus is rare.

Differential Diagnosis

β-Blocker overdoses present with bradycardia and hypoten-

sion; these findings also can occur with barbiturate intoxica-

tion and in cases of ingestion of some antiarrhythmics such

as mexiletine.

Treatment

A. Decontamination—In both β-blocker and calcium

channel blocker overdoses, patients who present soon after

ingestion of a significant amount of the drug should be con-

sidered for gastric lavage. Activated charcoal should be given;

repeat doses may be helpful. Patients who are initially stable

and who remain so need only be observed and monitored for

12–24 hours.

CHAPTER 36

768

B. Specific Therapy—

1. β-Blocker overdose—

a. Glucagon—Glucagon has been used with significant

success in patients with symptomatic overdoses of β-blockers

and is considered to be the drug of choice. It is effective

because its effects are independent of β-receptors, and it has

both inotropic and chronotropic effects. The dose used is

higher than that used for stimulating gluconeogenesis. The

recommended initial dose is 0.05 mg/kg intravenously, fol-

lowed by an infusion of up to 0.07 mg/kg per hour as needed.

It is important to be certain that the preparation used for

these doses does not contain phenol as a diluent because even

small amounts of phenol may be toxic. The most common

side effects of this dose of glucagon are nausea and vomiting.

b.

β

-Agonists—β-Adrenergic agonists have been used to

treat β-blocker overdoses with varying success. Since use of

these agents requires quantities sufficient to overcome the

competitive blockade at the receptor, the necessary doses

may be prohibitively high. Agonists may be tried empirically,

but if excessive doses are used with minimal effect, the drug

should be discontinued.

c. Atropine—Atropine, the agent usually first used to treat

symptomatic bradycardia, may have little effect in cases of β-

blocker toxicity because these rhythms are not vagally medi-

ated. When used, a dose of not more than 1 mg intravenously

should be administered. Use of external or transvenous pac-

ing has been reported, but the heart is often refractory to

normal pacing potentials, and the pacemaker may not cap-

ture despite the use of high voltage settings.

2. Calcium channel blocker overdose—

a. Calcium—Calcium channel blocker overdoses have

been treated with a variety of medications with varying suc-

cess. Calcium intuitively would seem to be appropriate ther-

apy, but its use has been disappointing. This result is not

surprising, however, because the calcium channels are

blocked, and this effect is not easily overcome with additional

calcium. Calcium is relatively nontoxic, however, and admin-

istration of calcium chloride, 5–10 mL of a 10% solution, is

probably indicated in most cases of symptomatic calcium

channel blocker toxicity.

b. Glucagon—As with β-blocker overdoses, glucagon is

useful in managing patients with calcium channel blocker

ingestion, although results have been less impressive. Dosing

is the same as that used in treating β-blocker toxicity.

c. Atropine—Atropine has been used to treat bradydys-

rhythmias and heart block but has proved to be relatively

ineffective. If the patient does not respond to 1 mg intra-

venously, use of atropine should be discontinued.

Transvenous pacing may be necessary and may require high

voltage settings outputs for capture.

d. Pressors—Dobutamine and dopamine infusions have

been used in these ingestions with varying results. These

agents may be tried in patients whose hypotension does not

respond to fluid administration and use of glucagon.

Norepinephrine also may be used.

DeWitt CR, Waksman JC: Pharmacology, pathophysiology and

management of calcium channel blocker and beta-blocker

toxicity. Toxicol Rev 2004;23:223–38. [PMID: 15898828]

Kerns W 2

nd

: Management of beta-adrenergic blocker and calcium

channel antagonist toxicity. Emerg Med Clin North Am

2007;25:309–31. [PMID: 17482022]

Love JN et al: Acute beta blocker overdose: Factors associated with

the development of cardiovascular morbidity. J Toxicol Clin

Toxicol 2000;38:275–81. [PMID: 10866327]

Newton CR, Delgado JH, Gomez HF: Calcium and beta receptor

antagonist overdose: A review and update of pharmacological

principles and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med

2002;23:19–25. [PMID: 16088594]

Digoxin

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Weakness, fatigue.

Palpitations.

Nausea, anorexia.

Visual complaints.

General Considerations

Digitalis is found in commercially prepared medications and

is also naturally occurring in plants such as oleander; toxic-

ity may be seen in patients exposed to medications or with

plant toxicity.

Digitalis preparations (eg, digoxin and digitoxin) have

two therapeutic effects. The first is to increase vagal tone,

which leads to conduction blockade at the atrioventricular

node and results in decreased chronotropy. The second is to

inhibit the myocardial Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase pump, which nor-

mally pumps calcium and sodium out of the cell and potas-

sium into it. Inhibition causes the intracellular calcium

concentration to rise, resulting in increased contractile force

(ie, positive inotropic effect). In the patient suffering from

digitalis toxicity, inhibition of the pump leads to excessive

extracellular potassium and intracellular sodium and cal-

cium, causing exaggerations of the therapeutic effects of the

drug. Toxicity is manifested by cardiac, GI, neurologic, and

electrolyte abnormalities.

Many of the symptoms of digitalis toxicity are nonspe-

cific. Patients may develop digitalis toxicity even when they

have normal blood levels of the drug if they have an under-

lying condition that sensitizes them to its effects (eg,

hypokalemia). Conversely, patients with elevated levels may

show no evidence of toxicity. The diagnosis of digitalis toxi-

city, therefore, often requires that the treating physician

know the patient groups at risk and suspect the diagnosis in

the appropriate setting. Table 36–9 summarizes the factors

that predispose to the development of digitalis toxicity.

Patients with any of these factors who are also taking digitalis

POISONINGS & INGESTIONS

769

should be evaluated for possible digitalis toxicity when the

clinical setting is suggestive.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Over 80% of patients with digi-

talis toxicity will complain of weakness, nausea, anorexia,

fatigue, and visual complaints. The visual complaints may be

a clue to making this diagnosis. The patient may complain of

yellow or green vision or of halos around objects—in addi-

tion to other visual disturbances such as photophobia or

transient amblyopia. Other complaints include vomiting,

headache, diarrhea, and dizziness.

B. Electrocardiography—Patients with significant cardiac

toxicity may not manifest either GI or neurologic effects.

Cardiac toxicity is due both to the increased vagal effects of

the drug and to the effects on the Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase pump. In

general, cardiac toxicity results from depression of impulse

formation or conduction (vagally mediated) and from

enhancement of automaticity (caused by blocking the

Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase pump). Virtually any rhythm disturbance

can be observed in digitalis-toxic patients.

Effects on the sinus node lead to bradycardia, sinoatrial

block, and sinus arrest. Increased irritability and automatic-

ity in the atria cause atrial tachycardia and can produce

atrial fibrillation or flutter. The ventricular rate is often nor-

mal or slow as a result of the conduction block caused by

the drug. Digitalis effect in the atrioventricular node can

cause atrioventricular block or junctional rhythm. In fact,

patients with digitalis toxicity may show “regularized”

atrial fibrillation—that is, a regular junctional rhythm with

a background of atrial fibrillation owing to the high degree

of atrioventricular block. The effect in the ventricles may

cause premature ventricular contractions (the most common

digitalis toxic rhythm), ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular

fibrillation.

C. Laboratory Findings—Hyperkalemia may be observed in

acute ingestions owing to the effect of digitalis on the

Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase pump and the resulting shift of potassium to

the extracellular space. This effect is not prominent in

patients who are maintained on digitalis on a chronic basis

and develop toxicity.

Evaluation of the patient with suspected digitalis toxicity

includes a serum digitalis level, serum electrolytes (including

magnesium and calcium), BUN, and serum creatinine. An

arterial blood gas analysis or pulse oximetry should be per-

formed to ensure that the patient is not hypoxic. An ECG

also should be obtained.

Differential Diagnosis

Symptoms of digitalis intoxication are nonspecific and are

not infrequently misdiagnosed as gastroenteritis or a viral

syndrome. The bradydysrhythmias may be associated with

other medications, including β-blockers and calcium chan-

nel blockers. The observed ectopy also can occur with elec-

trolyte disorders, particularly hypokalemia, and in patients

who are hypoxic or in those with cardiac ischemia.

Treatment

A. Decontamination—In the patient with suspected digitalis

toxicity, it is crucial to determine whether the toxicity is acute,

chronic, or acute on chronic. Although the same general care

principles apply to all three situations, patients with an acute

overdose may need several additional measures such as gastric

emptying, which should be considered if the patient presents

within 1 hour of the ingestion. If performed, lavage should be

done carefully because all gastric emptying techniques cause

increased vagal tone and may lead to worsening of any brady-

dysrhythmias or blocks. Pretreatment with atropine may have

minimal effect owing to digoxin’s blocking effect on the atri-

oventricular node. Whether lavage is performed or not, char-

coal, 50–100 g orally, should be given to adsorb any digitalis

remaining in the GI tract. Repeat-dose activated charcoal may

be effective in enhancing elimination of the drug.

Cholestyramine, which binds digitalis in the gut, also has

been used for this purpose in doses of 4–8 g orally, but it has

no particular advantage over charcoal. Drug levels should not

be drawn until at least 6 hours after the acute ingestion

because it takes that long for the drug level to equilibrate, and

levels obtained sooner may be misleadingly high.

In most cases of chronic toxicity, withdrawal of the drug

and a period of observation are all that are required for treat-

ment. In cases of both acute and chronic toxicity, forced

diuresis, hemoperfusion, and hemodialysis have been shown

to be ineffective in removing digitalis owing to its high

degree of protein binding.

B. Management of Electrolyte Abnormalities—Patients

who develop hyperkalemia should be treated with the

standard treatment regimen. It is important to note, how-

ever, that some of these measures may be ineffective in the

presence of digitalis toxicity. Use of bicarbonate and the

Table 36–9. Predisposing factors in digitalis toxicity.

Increased Sensitivity Increased Drug Level

Electrolyte disturbances

Hypokalemia

Hypernatremia

Hypercalcemia

Hypomagnesemia

Cardiac abnormalities

Ischemia

Cardiomyopathy

Conduction abnormalities

Hypoxemia

Drugs

Verapamil

β-blockers

Diuretics

Renal disease

Drugs

Quinidine

Verapamil

Amiodarone

CHAPTER 36

770

administration of glucose and insulin intravenously require

an intact Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase pump to reduce the elevated potas-

sium and may not produce the desired effect of lowering the

potassium level. Intravenous calcium is contraindicated

because it sensitizes the patient further to the toxic effects of

the digitalis. Sodium-potassium exchange resins are effective

and probably constitute the first choice in treating hyper-

kalemia from digitalis toxicity (polystyrene sulfonate, 15 g in

20–100 mL of syrup orally one to four times daily or 30–50

g in 100 mL of water per rectum every 6 hours). Dialysis is

also effective and can be used if hyperkalemia is life-

threatening or refractory to exchange-resin treatment.

Digitalis antibodies (see below) are also effective in

treating hyperkalemia. A serum potassium level over 5

meq/L in the setting of an acute overdose is an indication for

treatment with antidigitalis antibodies.

C. Treatment of Arrhythmias—The major and most life-

threatening toxicity associated with digitalis is cardiotoxicity.

Bradydysrhythmias, owing to the increased vagal tone,

should be treated with atropine starting with doses of 0.5 mg

intravenously. Doses can be repeated at 5-minute intervals as

necessary to a total dose of about 2 mg (0.3 mg/kg). If the

bradydysrhythmias are refractory to atropine, electrical pac-

ing may be necessary.

Tachydysrhythmias or rhythms resulting from increased

automaticity should be treated in a stepwise approach. First,

if the patient is hypokalemic (serum potassium <3.5 meq/L),

particularly if the patient is suffering from chronic toxicity,

potassium should be gently replenished, with frequent moni-

toring of the serum potassium level. Magnesium should be

given to virtually all patients with tachydysrhythmias except

those with elevated magnesium levels or those with renal fail-

ure. The optimal dose is unknown, but 2 g of magnesium sul-

fate intravenously over 20–30 minutes appears effective. In

patients whose tachydysrhythmia does not respond to elec-

trolyte replacement or who have contraindications to elec-

trolyte replacement, lidocaine should be used. If the patient’s

tachydysrhythmias persist despite adequate lidocaine dosing,

phenytoin poses an effective alternative, aiming for a thera-

peutic level of 10–20 μg/mL. Cardioversion is safe when used

in patients who have normal digitalis levels and no evidence

of toxicity. However, cardioversion in patients with digitalis

toxicity can lead to refractory ventricular tachycardia, ventric-

ular fibrillation, or asystole. It should be avoided if possible in

this group of patients, and all attempts should be made to

treat dysrhythmias medically. However, in some cases, car-

dioversion may be necessary to regain a perfusing rhythm. If

needed, it is critical that the lowest possible energy level be

used to achieve cardioversion. If possible, pretreatment with

lidocaine may be prudent.

D. Antibodies—Digoxin-specific antibodies (digoxin immune

Fab [ovine]) are a vital addition to the armamentarium for

treating digitalis toxicity, but their use should be limited to very

specific situations. These antibodies are sheep serum Fab frag-

ments that have a high affinity for digoxin—higher than the

affinity of digoxin for Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase. They circulate in the

intravascular space and diffuse into the extracellular space,

where they bind to free digoxin. The complex formed has no

biologic activity and is excreted in the urine. The intracellular-

to-extracellular gradient produced by the binding of extracel-

lular free digoxin causes intracellular digoxin to diffuse from

within the cells to be bound to the antibody and subsequently

excreted. Indications for use of these antibodies are listed in

Table 36–10. In general, digitalis-specific antibody should be

used when there are life-threatening dysrhythmias that do not

respond to conventional therapy, in patients with an initial

potassium level of greater than 5 meq/L (particularly in acute

ingestions), in patients who have ingested more than 10 mg of

digoxin (4 mg in children), and in those who have a steady-

state digoxin level of greater than 10 ng/mL.

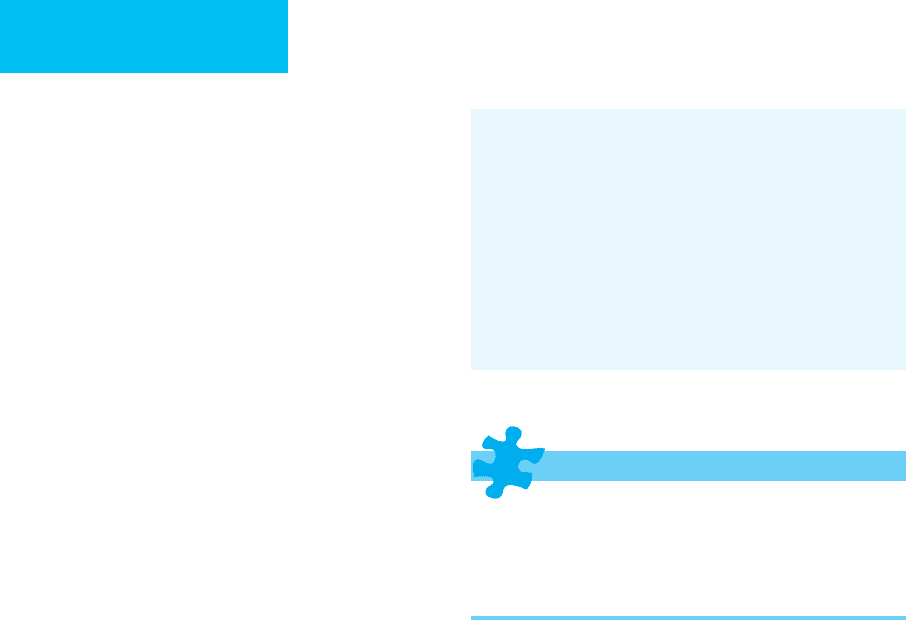

Dosing of digoxin antibodies is based on the fact that

each vial contains 40 mg antibody and will bind 0.6 mg

digoxin or digitoxin. The formula for calculating the dose of

antibody in a particular patient is shown below:

Life-threatening dysrhythmias

Serum potassium >5 meq/L

Acute ingestion of >10 mg of digoxin (>4 mg in children)

Steady-state digoxin level >10 ng/mL

Table 36–10. Indications for therapy with digoxin

antibodies.

POISONINGS & INGESTIONS

771

In patients with life-threatening complications who have

ingested an unknown amount, or if the blood level is

unavailable, a dose of 20 vials (800 mg) should be given.

Dysrhythmias are treated successfully with these antibod-

ies in about 70% of patients. The rhythms usually respond

within 20–60 minutes of administration of the antibody. Side

effects are generally mild. Up to 15% of patients may develop

minor allergic reactions, and some patients with preexisting

congestive heart failure may have an exacerbation owing to

the volume of fluid used to infuse the antibodies. It is impor-

tant to note that measuring digoxin levels after giving anti-

bodies is unreliable for up to 7 days after their

administration. Levels tend to rise to alarming levels because

so much of the drug ends up in the circulation bound as the

inactive antibody complex.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

The treating physician must understand the indications for

digoxin antibodies and use them appropriately. Patients who

have minor manifestations of digitalis toxicity such as GI

complaints or visual changes and those with evidence of car-

diac toxicity that does not need intervention or responds to

conventional therapy do not need this treatment. In addition,

patients with elevated digitalis levels but without evidence

of toxicity do not need treatment unless their levels are over

10 ng/mL at steady state. The levels should be measured at least

6–8 hours after the ingestion or the last dose of the medication.

Critchley JA, Critchley LA: Digoxin toxicity in chronic renal fail-

ure: Treatment by multiple dose activated charcoal intestinal

dialysis. Hum Exp Toxicol 1997;16:733–5. [PMID: 9429088]

Dawson AH, Whyte IM: Therapeutic drug monitoring in drug

overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:97–102S. [PMID:

11564057]

Eddleston M et al: Anti-digoxin Fab fragments in cardiotoxicity

induced by ingestion of yellow oleander: A randomised, con-

trolled trial. Lancet 2000;355:967–72. [PMID: 10768435]

Van Deusen SK, Birkhahn RH, Gaeta TJ: Treatment of hyper-

kalemia in a patient with unrecognized digitalis toxicity. J Toxicol

Clin Toxicol 2003;41:373–6. [PMID: 12870880]

Acetaminophen

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nausea and vomiting.

Jaundice.

Right upper quadrant pain.

Asterixis.

Lethargy and coma.

Bleeding.

Hypoglycemia.

General Considerations

Acetaminophen is an antipyretic and analgesic medication

available over the counter generically and in several brand-

name preparations. It is also used commonly in many com-

bination medications, both over the counter and available by

prescription. Overdose may occur inadvertently or inten-

tionally. Patients may ingest excessive doses of acetamino-

phen in an attempt to treat their own pain, being unaware of

the potential for toxicity. In the intentional overdose, treating

physicians must be aware that many medications contain

acetaminophen as a component of a combination prepara-

tion, and what might otherwise be a relatively benign inges-

tion from the other active ingredients in the medication

becomes a potentially lethal one in light of the amount of

acetaminophen consumed.

Acetaminophen is normally metabolized by the liver to

non-toxic compounds. If these pathways are saturated, a

toxic intermediate (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine) is

formed that is detoxified by glutathione. Excessive amounts

of acetaminophen deplete glutathione stores, leading to

accumulation of high levels of these toxic metabolites. The

major toxicity is hepatotoxicity, with hepatocyte necrosis

and, in severe cases, frank liver failure. N-Acetylcysteine, the

antidote for this toxicity, acts by enhancing glutathione stores

and providing a glutathione substitute to allow for detoxifi-

cation of the toxic metabolites.

Susceptibility to toxicity is variable. Patients with liver

disease or severe malnutrition are more sensitive, whereas

children under 9–12 years of age are more resistant than their

adult counterparts. Toxic doses vary; in adults, doses of less

than 125 mg/kg are rarely toxic unless the patient has preex-

isting liver disease or malnutrition. Doses of 125–250 mg/kg

produce variable toxicity, with some patients developing sig-

nificant liver damage at these levels. Doses over 250 mg/kg

commonly place the patient at risk to develop massive

hepatic necrosis and liver failure. Patients with severe hepa-

totoxicity eventually die from massive liver failure 4–18 days

after ingestion. Among patients who recover, liver enzymes

begin to normalize 5 days after ingestion, and full recovery

occurs within 3 months. Chronic liver disease after aceta-

minophen ingestion is extremely rare in patients who were

healthy prior to ingestion.

Clinical Features

A. History—The treating physician must be aware of the

potential for acetaminophen toxicity in virtually all patients

with intentional overdoses because of the widespread avail-

ability of this compound in combination preparations. In

addition, patients may unintentionally take excessive

amounts of acetaminophen to treat themselves for painful

conditions, not knowing that this drug may be toxic.

B. Symptoms and Signs—Despite ingesting potentially

lethal amounts of the agent, patients with acetaminophen

overdose often are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic

CHAPTER 36

772

in the first 24 hours. GI complaints such as nausea and

vomiting are common in large overdoses but may not be

seen in all serious overdoses. Patients also may be somewhat

lethargic and diaphoretic. Twenty-four to forty-eight hours

after ingestion, the patient feels well; however, hepatotoxicity

begins during this time, and levels of hepatic enzymes begin

to rise. Three to four days after significant ingestion, the

patient presents with progressive hepatic damage, nausea,

vomiting, jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, asterixis,

lethargy, coma, and bleeding, and hypoglycemia may develop.

C. Laboratory Findings—The single most important labo-

ratory test in patients who present after acetaminophen

ingestion is the acetaminophen level. A serum sample

should be drawn at least 4 hours after an acute single inges-

tion; levels drawn before this 4-hour time delay are unreli-

able in predicting toxicity. The acetaminophen treatment

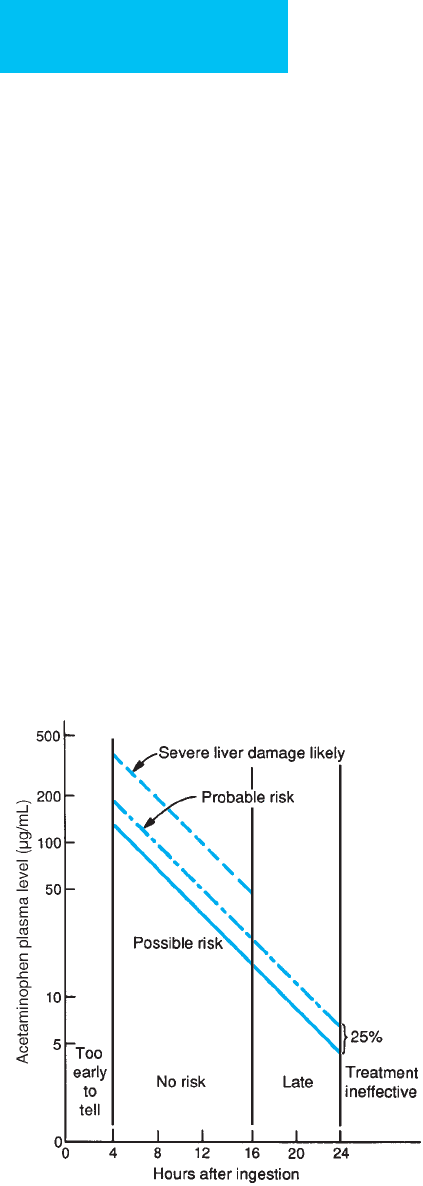

protocol nomogram (Figure 36–1) is used to ascertain

patient risk. In general, patients who have a 4-hour level of

over 150 μg/mL should be regarded as toxic and treated

accordingly.

Patients with significant ingestions should have their liver

enzymes and coagulation studies checked at least once every

12–24 hours and should be monitored closely for hypo-

glycemia, which is common among those with hepatotoxicity.

Differential Diagnosis

Liver failure may be caused by a number of other toxins, most

commonly chronic ethanol abuse. Acute ingestions such as

cyclopeptide toxicity following mushroom ingestion also

cause liver damage. Shock liver and massive hepatic necrosis

from hepatitis also may produce a similar clinical picture.

Treatment

A. Decontamination—All patients who present within 1 hour

of ingesting a potentially lethal amount of acetaminophen-

containing medications should be considered for gastric

emptying. Use of activated charcoal is somewhat controver-

sial because activated charcoal binds and prevents the

absorption of both acetaminophen and its antidote, acetyl-

cysteine (N-acetylcysteine). The charcoal may bind up to

40% of the acetylcysteine. However, increasing the acetylcys-

teine dose can provide adequate absorption despite the use of

charcoal. Therefore, if charcoal is used, the acetylcysteine dose

should be adjusted accordingly.

Patients who present more than 4–6 hours after inges-

tion already have absorbed the acetaminophen, making

gastric decontamination and charcoal administration rela-

tively ineffective. It should be noted, however, that patients

may have ingested other medications along with the aceta-

minophen that may respond to repeated-dose charcoal

treatment if the ingested agent is one that can be recovered

in this way.

B. Acetylcysteine—To date, there are no reliably effective

methods for enhancing the elimination of acetaminophen

already absorbed from the gut. Therefore, antidote therapy

is the mainstay of treatment for patients with potentially

toxic ingestions. Acetylcysteine is indicated in patients who

have toxic levels, as determined by the treatment nomo-

gram, and in those who may have ingested toxic amounts

of acetaminophen and present 8 hours or more after inges-

tion (see Figure 36–1). Acetylcysteine is most effective

when given within the first 8 hours after ingestion; after

that time, efficacy decreases with increasing delay. There is

no benefit to giving acetylcysteine in the first 4 hours after

ingestion, so treating the patient with acetylcysteine can

wait until the acetaminophen level is known if this infor-

mation will be available within 8 hours of ingestion. If the

result will be delayed beyond the 8-hour window and the

patient ingested a significant amount of acetaminophen,

acetylcysteine therapy should be started empirically and

can be discontinued if the level obtained falls in the non-

toxic range.

Acetylcysteine usually is given orally. The loading dose is

140 mg/kg, and subsequent doses of 70 mg/kg then are given

every 4 hours, typically for a total of 17 doses. A 2-day regi-

men also has been used successfully in selected patients.

Patients with acetaminophen toxicity may have significant

nausea and vomiting, which may make oral administration

of acetylcysteine difficult. As a rule, patients who vomit

Figure 36–1. Acetaminophen treatment protocol.

(Adapted from Rumack BH et al: Acetaminophen overdose:

662 cases with evaluation of oral acetylcysteine treatment.

Arch Intern Med 1981;141:382 [PMID: 7469629].)

POISONINGS & INGESTIONS

773

within 1 hour of receiving their oral acetylcysteine dose

should have that dose repeated. In addition, several measures

can be taken to minimize this difficulty. Antiemetics (eg,

prochlorperazine, metaclopramide, or ondansetron) should

be used. If they prove inadequate, the acetylcysteine may be

administered via an NG tube.

Some patients with toxic acetaminophen levels may have

persistent vomiting despite the preceding measures, preclud-

ing enteric administration of acetylcysteine. In this situation,

intravenous acetylcysteine is indicated and can be lifesaving.

Recently, an intravenous formulation of N-acetylcysteine was

approved for use in the United States. Dosing is the same as

for the oral route.

Common complications of intravenous acetylcysteine

treatment are rashes and urticaria. Serious reactions are rare.

Complications are minimized when acetylcysteine is deliv-

ered in at least 250 mL of diluent and infused over 1 hour.

C. Other Measures—Supportive care, including administra-

tion of vitamin K and lactulose, is indicated in patients with

coagulopathy or encephalopathy, respectively. In severe cases

refractory to supportive care, liver transplantation may be

necessary.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Administration of acetylcysteine beyond 24 hours after acet-

aminophen ingestion has been shown to have little effect.

Despite this information, and because there are few treat-

ment options other than supportive care and liver transplan-

tation in severely toxic cases, acetylcysteine probably should

be used in these situations. The duration of treatment is also

controversial. Currently, a 72-hour course is considered the

standard of care, but studies have shown that a 48-hour

course may be just as effective.

American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies

Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Critical Issues in the

Management of Patients Presenting to the Emergency

Department with Acetaminophen Overdose, Wolf SJ et al:

Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of patients pre-

senting to the emergency department with acetaminophen over-

dose. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:292–313. [PMID: 17709050]

Broughan TA, Soloway RD: Acetaminophen hematoxicity. Dig Dis

Sci 2000;45:1553–8. [PMID: 11007105]

Dart RC et al. Acetaminophen poisoning: An evidence-based con-

sensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol

(Phila) 2006;44:1–18. [PMID: 16496488]

Dawson AH, Whyte IM: Therapeutic drug monitoring in drug over-

dose. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:97–102S. [PMID: 11564057]

Gunn VL et al: Toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold med-

ications. Pediatrics 2001;108:E52. [PMID: 11533370]

Gyamlani GG, Parikh CR: Acetaminophen toxicity: suicidal vs

accidental. Crit Care 2002;6:155–9. [PMID: 11983042]

Larson AM et al. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure:

Results of a United States multicenter, prospective study.

Hepatology 2005;42:1364–72. [PMID: 16317692]

Salicylates

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nausea and vomiting.

Tinnitus.

Diaphoresis.

Hyperventilation.

Confusion and lethargy.

Convulsions and coma.

Cardiovascular failure.

General Considerations

Salicylates are used widely as antipyretics, analgesics,

antiplatelet agents, and anti-inflammatories; salicylates are

also found in topical preparations used to treat sore joints

and muscles. Not only are they available as aspirin preparations,

but they also constitute a common component of other com-

bination medications readily available over the counter.

Another source of salicylates is oil of wintergreen; this for-

mulation contains very large amounts of the drug, with con-

centrations as high as 7 g per teaspoon (compared with

325–650 mg per tablet in most aspirin preparations).

When taken orally, salicylates are absorbed rapidly from

both the stomach and the small bowel. Peak blood levels

occur 2 hours after ingestion of a normal dose. In therapeu-

tic doses, salicylates undergo hepatic metabolism and renal

excretion with a half-life of 4–6 hours. In the event of an

overdose, the hepatic enzymes become saturated, and metab-

olism changes from first-order (concentration-dependent)

to zero-order (concentration-independent) kinetics. Under

these circumstances, the drug’s half-life increases dramati-

cally to 18–36 hours. In the event of an overdose, renal excre-

tion of the unchanged salicylate becomes the major pathway

of drug elimination.

Salicylates produce respiratory alkalosis by directly stim-

ulating the CNS respiratory center and by increasing its sen-

sitivity to changes in CO

2

and oxygen concentrations.

Salicylates also uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, which

leads to an increased metabolic rate with a resulting increase

in glucose utilization, oxygen consumption, and heat pro-

duction. Clinical effects of this uncoupling include hypo-

glycemia and fever. Inhibition of enzymatic components of

the Krebs cycle occurs, leading to an increase in pyruvate and

lactate that causes a elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis. As

a result of their stimulatory effects on lipid metabolism, sal-

icylates increase ketone formation.

Clinically, it is important to divide patients with salicylate

toxicity into two groups: those who take the medication on a

chronic basis and those who have taken an acute overdose.

Patients who use aspirin chronically, such as the elderly or

CHAPTER 36

774

patients with arthritis, may present with unintentional over-

dose, and because they may have subtle clinical findings,

these patients are often misdiagnosed. As a result of this mis-

diagnosis, serious sequelae may develop, such as pulmonary

and CNS complications, with a mortality rate that

approaches 25%. The acute overdose group, on the other

hand, ingests this drug intentionally, and the acutely elevated

levels cause these patients to be more symptomatic and

therefore easier to diagnose. Acute ingestions of over 150

mg/kg are commonly associated with symptoms of toxicity.

Pulmonary and neurologic complications are less common

in this group, and the mortality rate is only 2%.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with mild to moderate sal-

icylate toxicity present with nausea, vomiting, tinnitus,

diaphoresis, and hyperventilation (eg, hyperpnea or tachypnea),

confusion, and lethargy. In cases of severe poisoning, convul-

sions, coma, and respiratory or cardiovascular failure may

occur. These symptoms of coma, seizures, hyperventilation, and

dehydration are more common in patients with chronic poison-

ing and are observed at lower salicylate levels (35–50 mg/dL).

Pulmonary edema, cerebral edema, gastritis with hematemesis,

and hyperpyrexia are observed occasionally.

B. Laboratory Findings—Salicylate levels are important in

the management of these patients. Peak levels after overdose

occur 4–6 hours after ingestion. This peak may be delayed or

prolonged if the patient ingested enteric-coated preparations

or if the patient develops gastric concretions of aspirin after

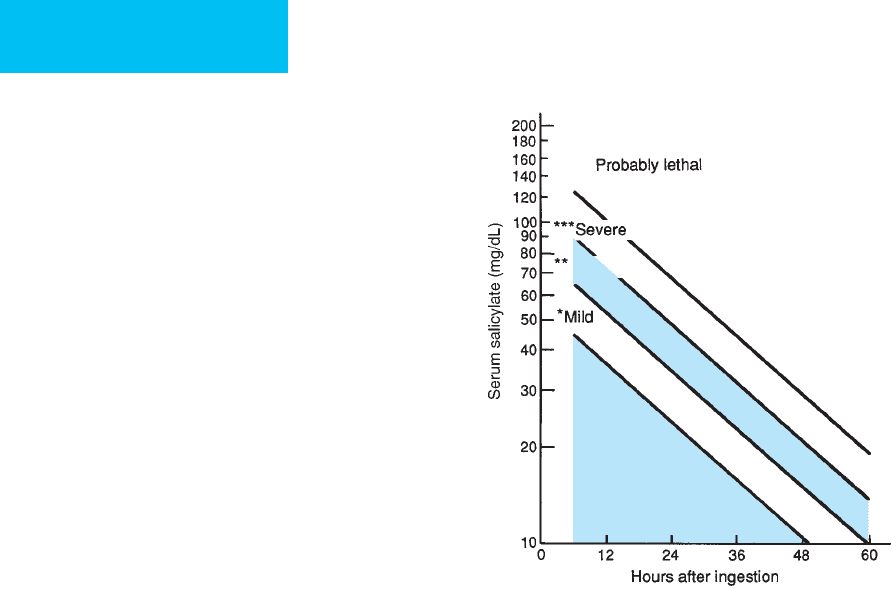

a massive ingestion. The Done nomogram (Figure 36–2)

estimates the severity of acute salicylate toxicity; it does not

apply in the patient with chronic toxicity. Levels obtained

6 hours or more after an acute ingestion can be plotted on the

nomogram and extrapolated to obtain the level of severity.

Common laboratory findings in a patient suffering from

salicylism are an elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis and

respiratory alkalosis. Other laboratory abnormalities may

include a prolonged prothrombin time, thrombocytosis,

hypernatremia, hyper- or hypoglycemia, ketonemia, lactic

acidemia, hypokalemia, and elevated liver transaminases. A

urine Phenistix test is usually positive, as is the ferric chloride

test (5–10 drops of 10% ferric chloride solution added to

urine that has been boiled for 1–2 minutes will turn the solu-

tion a burgundy color). Because coingestions are common,

an acetaminophen level should be obtained.

Differential Diagnosis

Because salicylism often presents with altered mental status

and an increased metabolic state, other entities that cause

this combination should be considered in the differential

diagnosis. Stimulants are the primary toxicologic cause, and

meningitis, sepsis, or encephalitis are possible infectious

sources. Pneumonia, renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and

alcoholic ketoacidosis also should be considered.

Treatment

A. Decontamination—Gastric lavage should be performed

in any patient with an ingestion of over 100 mg/kg within

1 hour before presentation. Gastric lavage also should be

considered in patients who have ingested massive amounts of

salicylates because they are prone to develop intragastric or

intraintestinal concretions; lavage may be helpful as late as

12–24 hours after ingestion in these cases. Activated charcoal

should be given to all patients with salicylate ingestion.

Repeated-dose activated charcoal administration should be

considered in patients with a significant exposure.

B. Alkaline Therapy—Alkalinization is the mainstay of

therapy for salicylate poisoning. It is indicated for patients

with significant acidemia and for those with blood salicylate

levels of over 35 mg/dL. In an alkaline environment, salicy-

lates remain in an ionized form and do not easily diffuse into

tissues. Alkalinization of the urine leads to trapping of the

salicylates in the renal tubules and facilitates excretion. The

goal of treatment is to achieve and maintain the urine pH at

8.0 or above. An adequate serum potassium level is required

before urinary alkalinization can be achieved, and patients

Asynotinatuc

Moderate

Figure 36–2. Nomogram for determining severity of

salicylate intoxication. Absorption kinetics assume acute

(one-time) ingestion of non-enteric-coated preparation.

(Redrawn and reproduced, with permission, from Done AK:

Salicylate intoxication: Significance of measurement of sali-

cylate in blood in cases of acute ingestion. Pediatrics

1960;26:800 [PMID: 13723722].)

POISONINGS & INGESTIONS

775

may require potassium supplementation to ensure adequate

blood levels. Patients receiving bicarbonate therapy should

be evaluated serially for the possible development of cerebral

or pulmonary edema.

C. Hemoperfusion and Hemodialysis—Hemoperfusion

and hemodialysis effectively remove salicylates from the

blood (Table 36–11). Hemodialysis may be preferable

because it also can be used to manage fluid and electrolyte

imbalances. Hemodialysis is specifically indicated for

patients who are deteriorating despite supportive and con-

ventional therapy, those with acute levels over 120 mg/dL if

drawn less than 6 hours after ingestion or 100 mg/dL if

drawn at 6 hours after ingestion despite the clinical presenta-

tion, those with chronic toxicity and levels of 60–70 mg/dL,

those with rising salicylate levels despite attempts at elimina-

tion, those with significant CNS effects, and those with pul-

monary edema or renal or hepatic failure.

D. Other Measures—Patients who develop seizures should

be treated with benzodiazepines or phenobarbital.

Hypotension should be treated with fluids and vasopressors.

Pulmonary edema may develop as a result of capillary dam-

age from salicylates and can be exacerbated by aggressive fluid

therapy. Development of pulmonary edema may require

intubation and mechanical ventilation with positive end-

expiratory pressures. Hemodialysis is frequently required in

these instances.

Chyka PA et al: Salicylate poisoning: An evidence-based consensus

guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila)

2007;45:95–131. [PMID: 17364628]

Hofman M, Diaz JE, Martella C: Oil of wintergreen overdose. Ann

Emerg Med 1998;31:793–4. [PMID: 9624330]

O’Malley GF: Emergency department management of the

salicylate-poisoned patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am

2007;25:333–46. [PMID: 17482023]

Skelton H et al: Drug screening of patients who deliberately harm

themselves admitted to the emergency department. Ther Drug

Monit 1998;20:98–103. [PMID: 9485563]

Theophylline

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nausea and vomiting.

Tachycardia with atrial or ventricular dysrhythmias.

Hypotension.

Agitation, hyperreflexia, seizures.

Hypokalemia.

General Considerations

Although inhalational agents are now the first-line therapy

for reactive airways disease, theophylline is a phosphodiesterase

inhibitor that is still used for the treatment of this disorder.

It comes in several forms, including an elixir and tablets that

are absorbed rapidly. Drug levels usually peak 2–4 hours after

ingestion. Theophylline is also available as a sustained-

release preparation whose serum level peaks anywhere from

6–24 hours after ingestion.

As a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, theophylline produces

an increase in intracellular cAMP, a mediator of β-adrenergic

effects. In addition, at toxic levels, theophylline causes cate-

cholamine release from the adrenal medulla. Therefore, the

result of toxic levels of theophylline is excessive β-stimulation,

and most of the toxic effects are a result of this excessive cat-

echolamine activity. Theophylline toxicity also causes CNS

effects, the mechanism of which is unclear.

Theophylline toxicity, like that of salicylates, causes two

distinct clinical entities depending on whether the toxicity

results from acute ingestion or chronic intake. Acute toxicity

usually results from an intentional overdose in a patient not

already taking the medication. Chronic toxicity is usually an

inadvertent overmedication in a patient already maintained

on this drug. Patients with acute intoxications more com-

monly have metabolic abnormalities and tolerate higher lev-

els of the drug, often not demonstrating serious toxic effects

until the levels reach 80–100 mg/L. Patients with chronic tox-

icity, on the other hand, often do not demonstrate metabolic

abnormalities but may manifest serious toxicity at levels as

low as 40 mg/L. It is also important to note that in the patient

with chronic toxicity, the serum levels often do not correlate

with the severity of toxicity—that is, the patient with what

may appear to be a mildly elevated drug level may have life-

threatening toxic effects. This is particularly true in elderly

patients with chronic theophylline toxicity.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Theophylline toxicity causes GI,

cardiovascular, CNS, and metabolic abnormalities. As a result

of local gastric irritation and central effects, patients often

complain of nausea and vomiting. This is not universal,

Acute ingestion with levels over 120 mg/dL if drawn <6 hours after

ingestion, or over 100 mg/dL if drawn ≥6 hours after ingestion

Chronic toxicity with a salicylate level of 60–70 mg/dL

Deterioration despite conventional therapy

Significant central nervous system toxicity

Renal failure

Hepatic failure

Pulmonary edema

Rising salicylate levels despite attempts at decontamination

and elimination

Table 36–11. Indications for hemodialysis in salicylate

therapy.

CHAPTER 36

776

however, and patients may have other life-threatening toxic

effects without GI complaints.

Owing to the excessive β-stimulation, patients are often

tachycardic and prone to ventricular tachydysrhythmias.

Atrial dysrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and multifo-

cal atrial tachycardia, are also seen. As a result of the stimula-

tion of peripheral β

2

-adrenergic receptors and vasodilation,

these patients may develop hypotension. Decreased diastolic

pressure may be a warning sign that severe vasodilation is

developing.

Patients with theophylline toxicity demonstrate agitation,

hyperreflexia, and tremulousness. Seizures may develop and

are often the first CNS sign of toxicity; this is frequently the

case in patients with chronic toxicity. Seizures may be focal or

generalized and are often prolonged; status epilepticus is not

uncommon. Seizures may be refractory to anticonvulsant

therapy and can result in permanent brain damage or death.

B. Laboratory Findings—Hypokalemia is common with

acute ingestions; it occurs as a result of a theophylline-

induced intracellular shift of potassium. Theophylline toxic-

ity also causes hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, respiratory

alkalosis, and leukocytosis.

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to theophylline, toxic causes of altered mental

status, seizures, and cardiovascular abnormalities include tri-

cyclic antidepressants, anticholinergic agents, and phenoth-

iazines. Rarely, calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, and

overdoses of local anesthetic agents cause these findings.

Nontoxic causes include meningitis, sepsis, anaphylaxis, head

trauma, and hypoglycemia.

Treatment

A. General Measures—Basic supportive measures such as

intravenous access, hemodynamic monitoring, oxygen

administration, and airway management (as needed) should

be the first priority.

B. Correction of Hypotension—Hypotension should be

treated initially with infusion of crystalloid as a bolus of

250–500 mL over several minutes, repeated as necessary. If

infusions of balanced salt solution do not correct the

hypotension, or if the patient cannot tolerate the volume,

pressors may be necessary. Pure α-agonists such as phenyle-

phrine are preferable to pressors with beta-effects that may

exacerbate theophylline toxicity. Propranolol also may be

used to treat the hypotension in patients who do not have

contraindications to using this drug. The mechanism for the

efficacy of propranolol lies in the fact that it blocks the

peripheral β

2

-adrenergic receptors that participate in the

peripheral vasodilation of theophylline toxicity.

C. Antiarrhythmics—Patients who have severe supraven-

tricular dysrhythmias from theophylline toxicity (eg, severe

sinus tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, or multifocal

atrial tachycardia) may be treated with verapamil or β-

blockers if there are no contraindications to using these

drugs. Ventricular dysrhythmias should be treated by cor-

recting hypokalemia and administering lidocaine.

D. Anticonvulsants—Seizures should be treated with ben-

zodiazepines, phenobarbital, or phenytoin singly or in com-

bination. Seizures accompanying theophylline toxicity are

frequently refractory to treatment. It may be necessary to

either place the patient under general anesthesia or use neu-

romuscular blockade to prevent acidosis and rhabdomyoly-

sis and to facilitate ventilation. Patients still may have

electrical seizure activity despite being anesthetized or para-

lyzed. Electroencephalographic monitoring should be used

to make this determination.

E. Decontamination—Once the patient is stabilized hemo-

dynamically, prevention of further absorption of the drug is

the next goal. Patients who present within the first hour after

ingestion should be considered for gastric lavage; because

seizures may be precipitous, intubation is often indicated

before lavage if the patient manifests signs of significant tox-

icity. If the patient ingested a sustained-release form of theo-

phylline, lavage should be considered as long as 3–4 hours

after ingestion.

Charcoal administration is pivotal in treating patients

with theophylline toxicity. All patients, regardless of the time

since ingestion, should receive activated charcoal, in a dose of

either 1–2 g/kg or 10 g of charcoal for every gram of theo-

phylline ingested. This can be given orally or via the lavage

tube. For patients who cannot drink the charcoal slurry, an

NG tube should be placed and the charcoal delivered directly

into the stomach. Serial charcoal dosing is a mainstay in the

treatment of theophylline toxicity. Charcoal avidly binds

theophylline, making this treatment akin to “gastrointestinal

dialysis.” Doses of 0.5–1 g/kg of charcoal every 2 hours dra-

matically decrease the half-life of theophylline. To prevent GI

fluid and electrolyte losses, it is essential not to give cathartics

with each dose of the charcoal. Cathartics should be given

with the first dose of charcoal only, and subsequent doses

should be a slurry of the charcoal only. If the serial charcoal

needs to be continued for more than 24 hours, cathartics can

be given once or twice daily as needed. If the patient has per-

sistent vomiting that precludes charcoal administration,

metoclopramide or ondansetron can be given intravenously.

In these patients, the charcoal may be better tolerated when

given as a continuous administration of 0.25–0.5 g/kg per

hour via an NG tube.

Despite appropriate treatment, some patients with theo-

phylline toxicity continue to have dysrhythmias, hypoten-

sion, and seizures. Following an acute ingestion, serum levels

of more than 90–100 mg/L are associated with more serious

toxic effects. After chronic intoxication, this toxic level is

approximately 60 mg/L. When drug concentrations reach

these levels, hemoperfusion or hemodialysis may be indi-

cated. Table 36–12 lists the major indications for initiating

hemodialysis or hemoperfusion therapy in patients with