Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CARE OF PATIENTS WITH ENVIRONMENTAL INJURIES

797

General Considerations

Spider and scorpion bites are particularly common in the

western United States. Only the female black widow spider

(Latrodectus mactans) is dangerous. Its venom contains a

potent neurotoxin that induces neurotransmitter release fol-

lowing interaction with a specific cell surface receptor. This

action affects mainly the neuromuscular junction and results

in unrestrained muscle contraction and severe cramping.

The local reaction at the site of envenomation is usually mild.

Venom from the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa)

contains sphingomyelinase D. It is primarily cytotoxic and

causes local tissue destruction. Hemolysis is the principal

systemic effect, and it is usually minor.

Most scorpion stings are harmless and produce only local

reactions. However, venom from Centruroides exilicauda con-

tains a neurotoxin that may cause severe systemic reactions.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Initially, a black widow spider

bite is painless. Symptoms begin within 10–60 minutes and

include severe pain and muscle spasms of the abdomen and

trunk. Headache, nausea, vomiting, and hyperactive deep

tendon reflexes may be present. Spasms give way to agoniz-

ing pain. Rigidity of the abdominal wall may be confused

with an intraabdominal catastrophe. Hypertension with or

without seizures develops uncommonly. Symptoms are

maximum at 2–3 hours after the bite and may persist for up

to 24 hours.

Brown recluse spider bites produce pain after 1–4 hours.

Initially, an erythematous area with a central pustule or hem-

orrhagic area appears. A bull’s-eye appearance of the lesion

may be noted because of an ischemic halo surrounded by

extravasated blood. Over several days, an ulcer may form,

which, if extensive, requires excision and skin grafting.

Systemic reactions are infrequent but may occur 1–2 days

after the bite and include massive hemolysis, hemoglobin-

uria, jaundice, renal failure, pulmonary edema, and dissemi-

nated intravascular coagulation.

Scorpion stings are extremely painful but often exhibit no

erythema or swelling. Light palpation of the area causes

extreme pain. Generalized reactions are not common but

may develop within 60 minutes: restlessness, jerking, nystag-

mus, hypertension, diplopia, confusion, and rarely seizures.

Death is uncommon.

Differential Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of black widow spider envenomation

can be easily confused with other common conditions, partic-

ularly those cases with minimal bite-related symptoms. In

some cases, the abdominal pain may mimic an acute

abdomen. Black widow spider envenomation should be con-

sidered in patients presenting with the acute onset of severe

pain and muscle cramps, particularly if the history is consis-

tent with spider bite.

Brown recluse spider bites are occasionally confused with

those of other insects. It should be remembered that spiders

usually bite only once, whereas other insects produce multi-

ple bites.

Treatment

A. Black Widow Spider Bites—The most effective treat-

ment options include specific antivenin alone or with a com-

bination of intravenous opioids and muscle relaxants.

Although calcium gluconate administration has been recom-

mended, it has not been shown to be effective. Intravenous

morphine and benzodiazepines are helpful in achieving relief

of symptoms. Antivenin should be considered in moderate to

severe cases but should be used with caution because it has

been associated with fatal reactions. Advanced life support

measures may be required for patients who develop cardio-

vascular collapse or respiratory failure.

B. Brown Recluse Spider Bites—Most patients can be

treated with supportive measures. Ice may be beneficial.

Exercise of the limb or application of heat will potentiate the

actions of the venom. Patients requiring admission to the

ICU are usually older, with systemic symptoms. Dapsone,

50–100 mg orally twice daily for 10 days, has been used in

patients who do not have glucose-6-phosphate dehydroge-

nase deficiency. Some authorities use oral erythromycin,

250 mg four times daily for 10 days, to control skin infection.

C. Scorpion Stings—Children and older adults must be

admitted to the ICU for observation. The affected part

should be immobilized and ice applied. A tourniquet must

not be used. Respiratory depression may result from the use

of tranquilizers. Opioid analgesics are particularly dangerous

because they seem to potentiate the toxicity of the venom.

Seizures, when present, usually can be controlled with intra-

venous diazepam or phenobarbital. Hypertension may

require the use of sympatholytic agents.

3. Marine Life Envenomations

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Pain at the site of envenomation.

Systemic symptoms subsequently.

Multiple wounds may be present.

General Considerations

Marine life envenomations are caused most commonly by

stingrays, jellyfish (Portuguese man-of-wars), scorpion

fish, and sea urchins. Although many victims can be

treated in the emergency department and released, critical

care may be required for hemodynamic and respiratory

complications.

CHAPTER 37

798

Clinical Features

A. Stingray—Multiple sites may be present, with pain and

swelling occurring immediately. Local hemorrhage also may

be present. Systemic symptoms, when present, include nau-

sea, vomiting, weakness, vertigo, tachycardia, and muscle

cramps. Syncope, paralysis, hypotension, and tachycardia

may occur with extensive envenomations.

B. Scorpion Fish—Central radiation of pain from the

wound may cause extreme discomfort requiring ICU admis-

sion for control. Systemic symptoms are manifest within the

first few hours after envenomation and include vomiting,

weakness, diarrhea, paresthesias, seizures, fever, hyperten-

sion, cardiac arrhythmias, and respiratory failure.

C. Sea Urchins—Sea urchin venoms contain several toxins,

including cholinergic compounds and neurotoxins. Multiple

spines usually are present in the skin and indicate the nature

of the contact. Systemic reactions include nausea and vomit-

ing, intense pain, paralysis, aphonia, and respiratory distress.

Treatment

A. Stingray—Wounds can be treated with local measures,

including warm soaks and lidocaine. Ice should not be applied.

Operative debridement may be required. Supportive therapy is

usually all that is required. Infection prophylaxis should be

instituted with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or tetracycline.

B. Scorpion Fish—Care is similar to that outlined for

stingray contact. Infection prophylaxis should be instituted

in a similar fashion. Seizures can be treated with phenobar-

bital, phenytoin, or diazepam.

C. Sea Urchins—Although pain can subside within a few

hours, paralysis may last for 6–8 hours and require intuba-

tion and mechanical ventilation until the patient has

regained sufficient strength.

Bogdan GM et al: Recurrent coagulopathy after antivenom treat-

ment of crotalid snakebite. South Med J 2000;93:562–6. [PMID:

10881769]

Dart RC et al: A randomized multicenter trial of crotalinae polyva-

lent immune Fab (ovine) antivenom for the treatment for cro-

taline snakebite in the United States. Arch Intern Med

2001;161:2030–6. [PMID: 11525706]

Dart RC et al: Efficacy, safety, and use of snake antivenoms in the

United States. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:181–8. [PMID:

11174237]

Forks TP: Brown recluse spider bites. J Am Board Fam Pract

2000;13:415–23. [PMID: 11117338]

Frundle TC: Management of spider bites. Air Med J 2004;23:224–6.

[PMID: 15224078]

Gold BS et al. North American snake envenomation: Diagnosis,

treatment and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am

2004;22:423–33. [PMID: 15163575]

Hall EL: Role of surgical intervention in the management of cro-

taline snake envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:175–80.

[PMID: 11174236]

Jasper EH et al: Venomous snakebites in an urban area: what are

the possibilities? Wilderness Environ Med 2000;11:168–71.

[PMID: 11055562]

Majeski J: Necrotizing fasciitis developing from a brown recluse

spider bite. Am Surg 2001;67:188–90. [PMID: 11243548]

Moss ST et al: Association of rattlesnake bite location with severity

of clinical manifestations. Ann Emerg Med 1997;30:58–61.

[PMID: 9209227]

Offerman SR et al: Does the aggressive use of polyvalent antivenin

for rattlesnake bites result in serious acute side effects? West J

Med 2001;175:88–91. [PMID: 11483547]

Perkins RA et al. Poisoning, envenomation and trauma from

marine creatures. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:885–90. [PMID:

14989575]

Scharman EJ et al: Copperhead snakebites: Clinical severity of local

effects. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:55–61. [PMID: 11423813]

Walter FG et al: Envenomations. Crit Care Clin 1999;15:353–86.

[PMID: 10331133]

Wendell RP: Brown recluse spiders: A review to help guide physi-

cians in non-endemic areas. South Med J 2003;96:486–90.

[PMID: 12911188]

Electric Shock & Lightning Injury

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Momentary or prolonged unconsciousness.

Cardiac arrhythmias.

Muscular pain, fatigue, headache.

Rhabdomyolysis and renal failure.

General Considerations

Electrical injuries account for more than 500 fatalities each

year in the United States. One-fifth of these deaths are due to

lightning. The number of nonfatal injuries may be three or

four times this number. Patients who have sustained electri-

cal injury or a lightning strike exhibit a number of signs

depending on the energy of the current conducted. Most

household electrical injuries are produced by alternating

current (50–60 Hz) in the 110–220-volt range. Direct current

usually produces less severe injuries for the same amount of

voltage. Electricity can cause partial- or full-thickness burns

with injury to the deeper tissues of the body. In some cases,

the burn injury at the entry and exit points may correlate

directly with the extent of underlying muscle injury, but

extensive deep injuries may be present with only minimal

superficial findings. Myonecrosis and rhabdomyolysis are

frequently present with higher-energy exposures.

Rhabdomyolysis may lead to renal failure if not recognized

and treated promptly. Compartment syndrome can occur in

extremities with resulting circulatory compromise.

Ventricular fibrillation may be present if the current pathway

has included the heart.

CARE OF PATIENTS WITH ENVIRONMENTAL INJURIES

799

A potential difference of more than 440 V is considered

high voltage. At greater than 1000 V, severe tissue destruction

occurs as a result of electrical energy being converted to heat.

Electrocution may be accompanied by arc and flash burns

(see Chapter 35). Associated injuries are a result of falls

owing to tetany of the major muscles.

Lightning strikes impart huge amounts of energy to their

victims. Cardiac and respiratory failure are responsible for

immediate deaths. Those surviving the immediate period are at

risk for delayed neurologic, visual, and otologic as well as mus-

culoskeletal complications. Although neurologic sequelae pre-

viously were thought to be transient, recent investigations have

demonstrated permanent injury in one-half of the victims.

Clinical Features

A. Electric Shock—Shock from household current commonly

produces transient loss of consciousness, although this may be

prolonged. Patients frequently have regained normal function

by the time they arrive in the emergency room, at which time

they complain of headache, muscle cramps, and fatigue.

Nervous irritability and a sensation of anxiety are other com-

mon findings. Patients with prolonged unconsciousness

should undergo CT scanning to rule out an associated cerebral

injury from a fall or direct injury. Cardiac arrhythmias typi-

cally are tachyarrhythmias, with atrial and ventricular fibrilla-

tion being the most common. Difficulty in breathing with

varying degrees of respiratory paresis or complete paralysis

requires immediate attention. Damage to skeletal muscles may

produce a spurious rise in the CK-MB fraction, leading to the

erroneous diagnosis of myocardial infarction.

Burn wounds often accompany electrocution victims.

These injuries are of three types: (1) direct burn, (2) arc

injury, or (3) flame burn from an associated ignition source.

Burn wounds are more common with higher-voltage injuries.

All patients with burn wounds should receive tetanus prophy-

laxis. Patients with more severe burns should be considered

for transfer after stabilization to a specialized burn center.

Additional management is discussed in Chapter 35.

B. Lightning Strike—Patients who require critical care after a

lightning strike usually are admitted for complications or sim-

ply for cardiac monitoring. Lightning victims may present with

paraplegia or quadriplegia that resolves over several hours. This

may be accompanied by autonomic instability. In cases of pro-

longed paresis, imaging studies should be obtained to rule out

a spinal injury. Electrocardiographic changes include nonspe-

cific ST-T-segment changes that may be accompanied by eleva-

tion of cardiac enzymes. Initial hypertension usually resolves

spontaneously and does not require treatment.

Lightning victims may have a number of associated find-

ings related to blunt trauma sustained at the time of impact.

Rib and long bone fractures in the extremities are particu-

larly common. Burns may be present but are superficial in

most patients and often require only superficial wound care.

Unlike those who have sustained electrical injuries, patients

with lightning injuries rarely develop myoglobinuria.

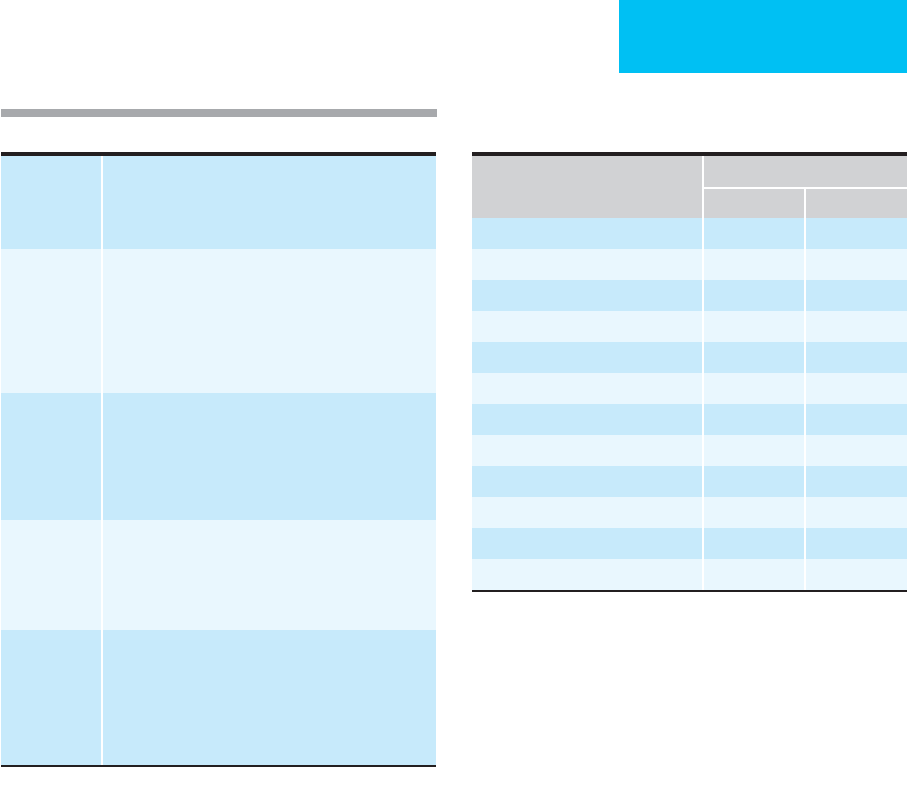

Treatment: Electric Shock

Patients suffering from electrical injuries should be admitted

to the ICU when the conditions outlined in Table 37–1 are

present.

A. General Measures—Most electrocution patients admit-

ted to the ICU already will have had the airway secured (if

necessary) and large-bore intravenous catheters inserted for

resuscitation and fluid management. Adequate urine output

must be ensured to prevent renal failure from myoglobin-

uria. The goal is to maintain a urine output of 75–100 mL/h.

Mannitol may be give as a bolus (1 g/kg) and then as an infu-

sion to maintain an osmotic diuresis as long as the urine con-

tains myoglobin (positive hemoglobin nitrotoluidine test).

Sodium bicarbonate may be added to alkalinize the urine

and prevent the precipitation of acid hematin. The calculated

fluid requirement is approximately 1.7 times the standard

fluid calculation based on the total body surface area burned.

Electrolytes should be monitored frequently during the

resuscitation period.

B. Arrhythmias—After initial stabilization, the most imme-

diate risk is from cardiac arrhythmia, particularly when the

electric current has passed through the thorax.

Antiarrhythmics and inotropic support should be instituted

when appropriate. However, most arrhythmias are self-

limited and infrequently cause hemodynamic abnormalities.

Atrial fibrillation occurs occasionally and usually will con-

vert without treatment. Electrocardiographic changes are

present in 10–30% of patients. The most common abnor-

mality is nonspecific ST-T-wave changes. Myocardial infarc-

tion is unusual, but patients with high-voltage injuries may

sustain direct myocardial damage. In these patients, close

monitoring of fluid therapy may be necessary to prevent pul-

monary edema.

C. Neurologic Sequelae—More than half of patients with

severe electrical injury develop loss of consciousness, but full

recovery usually ensues. Neurologic sequelae sometimes are

delayed and may develop days to years after the injury.

Deterioration of neurologic status may be of three types:

(1) ascending paralysis, (2) amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or

High-voltage electrocution

Burns >20% of BSA

Evidence of entrance and exit burns

Cardiac arrhythmias

Unconsciousness

Respiratory or motor paralysis

Multiple associated injuries

Prior medical compromise

Table 37–1. Criteria for ICU admission following electrical

injury.

CHAPTER 37

800

(3) transverse myelitis. Peripheral nerve injuries and motor

neuropathies result from demyelinization, vacuolization,

gliosis, and perivascular hemorrhage. The prognosis for

recovery of useful function is poor.

D. Burns—Most critical care required by victims of electri-

cal injury relates to burns. This subject is discussed in

Chapter 35.

Treatment: Lightning Strikes

The most severe complication of lightning injury is respira-

tory arrest caused by depression of the respiratory control

center. This can result in secondary cardiac arrest in an oth-

erwise salvageable patient. Surviving victims of lightning

strikes tend to have fewer complications than patients with

electrical injury. Early emergency resuscitation usually stabi-

lizes these patients to the point that only observation is nec-

essary. The need for cardiac monitoring for more than 24

hours is debatable. Most patients will be confused and have

anterograde amnesia covering a period of several days after

the incident. If neurologic deterioration is noted, CT scan-

ning or MRI should be obtained to exclude the possibility of

intracranial hemorrhage or other injury. In most cases, long-

term sequelae from lightning injuries are rare.

Fish RM: Electric injury: II. Specific injuries. J Emerg Med

2000;18:27–34. [PMID: 10645833]

Lee RC: Injury by electrical forces: Pathophysiology, manifesta-

tions, and therapy. Curr Probl Surg 1997;34:677–764. [PMID:

9365421]

Muehlberger T et al: The long-term consequences of lightning

injuries. Burns 2001;27:829–33. [PMID: 11718985]

O’Keefe-Gatewood M et al: Lightning injuries. Emerg Med Clin

North Am 2004;22:369–403. [PMID: 15163573]

Radiation Injury

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nausea and vomiting, diarrhea.

Weakness, dehydration.

Bone marrow depression.

Sepsis.

Severe neurologic changes.

Cardiovascular collapse.

General Considerations

Acute radiation syndrome consists of characteristic clinical

manifestations following accidental or therapeutic exposure

to ionizing radiation. In cases of unknown level of exposure,

knowledge of the manifestations enables the clinician to

estimate the exposure dose and determine appropriate

treatment.

Ionizing radiation can be either electromagnetic (eg, x-

rays and gamma rays) or particulate (eg, electrons, protons,

and neutrons). The power of penetration of these particles

is determined by the energy they carry. High-energy parti-

cles can travel deep into the body and cause severe damage

to tissues.

The principal lethal effect of radiation appears to be the

production of chemically active free radicals within cells that

damage essential macromolecules such as DNA. Very high

radiation doses will disrupt cell metabolism and result in

rapid cell death. Moderate radiation doses produce breaks in

double-stranded DNA. No visible effects occur until the cell

attempts mitosis. At that time, cell division may be arrested,

or the daughter cells may lack essential genetic material and

become nonfunctional. Small doses of radiation can produce

gene mutations. This may result in no observable effect or in

subsequent malignant transformation.

Individual tissues vary greatly in their sensitivity to radi-

ation damage. The most sensitive tissues are those that

require continued cellular proliferation for proper function,

such as the GI and hematopoietic systems. Acute radiation

syndrome is most pronounced in these systems. With very

high levels of exposure, dysfunction of the cardiovascular

and central nervous systems is also observed, most likely

resulting from direct organ injury.

Radiation Dosimetry

The rad is the unit of absorbed radiation dose. It is defined

as that quantity of radiation that deposits 100 ergs of energy

per gram of tissue. Clinically, a dose of radiation is often pre-

scribed in grays (Gy) (1 Gy = 100 rads; 1 rad = 1 cGy).

Clinical Features

Radiation injury is characterized by an acute phase, referred

to as the prodromal phase, and a subacute phase, character-

ized by bone marrow and GI dysfunction. The phases are

separated by a latent period of 1–3 weeks, during which time

the patient may be completely asymptomatic. The severity of

acute radiation injury is determined by the dose and the time

over which the exposure occurs. After exposure to less than

150 cGy, most patients have minimal or no prodromal symp-

toms. Slight depression of platelets and granulocytes may be

observed after a latent period of 30 days. Lymphocytes are

most sensitive to radiation and may be decreased.

Patients exposed to 150–400 cGy develop transient nau-

sea and vomiting 1–4 hours following exposure. After a latent

period of 1–3 weeks, GI symptoms occur: nausea, vomiting,

and bloody diarrhea. Bone marrow depression is manifest by

anemia, coagulopathy, and depressed immune function.

Susceptibility to infection is increased significantly.

An acute whole body exposure of 600–1000 cGy results in

an accelerated version of the acute radiation syndrome. GI

complications predominate in the early phase of the illness

CARE OF PATIENTS WITH ENVIRONMENTAL INJURIES

801

and may be life-threatening. Severe hematologic complica-

tions can be expected to develop in survivors.

A fulminating course is seen in patients sustaining acute

whole body exposure to higher doses. Vomiting occurs

shortly after exposure and is rapidly followed by diarrhea,

tenesmus, dehydration, and circulatory collapse. CNS mani-

festations may include ataxia, incoordination, weakness, con-

fusion, seizures, and coma. Death occurs within 48 hours.

Pericarditis with effusions and constriction are delayed

manifestations that develop several months after exposure.

Myocarditis can occur but is less common. If injury is mild,

full recovery is the rule.

Treatment

In cases of moderate radiation exposure, initial treatment is

supportive and uncomplicated. Immediate aggressive ther-

apy is not indicated because the prodromal symptoms usu-

ally are not severe and are self-limited. It is after the latent

period of 1–3 weeks that the more severe clinical manifesta-

tions of the syndrome develop. In cases in which severe

symptoms develop without a latent period, death is

inevitable, and only symptomatic care should be provided.

Patients with moderate to severe radiation exposure

should be admitted to the hospital and isolated. Care should

be exercised to limit patient and personnel movement

through the hospital in order to contain the radiation. Many

radioactive materials are in particulate form and will not

pass through the skin and are removed by washing. To this

end, clothes should be removed and stored in specially

labeled plastic bags. Showering or washing skin surfaces

removes most of the contamination. A Geiger counter

should be used to assess the adequacy of decontamination.

The process can be aided by hair removal. Undiluted house-

hold bleach (5% sodium hypochlorite) can be used after

soap and water. A dilute solution (1 part bleach to 5 parts

water) should be used around the face and wounds. Wounds

should be thoroughly debrided and irrigated to remove

radioactive material.

Fluid loss should be corrected with intensive intravenous

replacement. The blood count should be monitored care-

fully. Reverse isolation is required when the white blood cell

count falls below 1000/μL. Whole blood and platelet transfu-

sions are nearly always required because of anemia and bleed-

ing. When immunosuppression is apparent, blood products

should be irradiated with 5000 cGy before transfusion to

decrease the possibility of a graft-versus-host reaction.

Intestinal microorganisms are a major source of infection,

and prophylactic antibiotics directed against gram-negative

organisms should be administered. The appearance of clinical

signs of infection should prompt a thorough evaluation.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered until

culture results are obtained.

The use of chlorpromazine or promethazine in an

attempt to control radiation-induced vomiting should be

avoided. These medications depress gastric emptying and

may increase the risk of aspiration and subsequent pul-

monary infection.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Antidopaminergic agents appear to prevent radiation-

induced vomiting without causing gastroplegia. Clinical tri-

als suggest that domperidone may be effective, but more

controlled studies need to be completed.

In most cases of moderate to severe acute radiation

injury, exposure of the bone marrow is not uniform, and a

return of function can be anticipated. In cases of lethal expo-

sures, the use of bone marrow transplantation as a form of

therapy has been suggested. However, based on current expe-

rience, the likelihood of success cannot be adequately

ensured. Numerous problems exist in the potential applica-

tion of this type of therapy. It could not be used in a mass-

casualty situation because of the extensive resources required

for the treatment of individual patients. Additional problems

can be anticipated in securing suitable HLA-compatible

donors and in controlling graft-versus-host disease. This

treatment was attempted in 13 victims of the Chernobyl acci-

dent. Eleven of these patients died. It is not clear whether the

other two patients would have survived with conventional

supportive therapy.

A newer mode of treatment of pancytopenia is the stim-

ulation of hematopoietic tissue through the use of cytokines

and colony-stimulating factors. This has been demonstrated

to decrease the period of leukocyte count depression and to

elevate the nadir. Additional studies are required to establish

efficacy and optimal dosing regimens.

GI pathogen suppression may be accomplished by the

deliberate inoculation of the gut with nonpathogenic bacte-

ria such as lactobacilli. The theory is that this will result in

normalization of the intestinal flora that had been altered by

antibiotic therapy. Prolonged survival has been demon-

strated in animal models, but studies in humans are lacking.

Bice-Stephens WM: Radiation injuries from military and acciden-

tal explosions: A brief historical review. Mil Med

2000;165:275–7. [PMID: 10802999]

Leikin JB et al: A primer for nuclear terrorism. Dis Mon

2003;8:485–516. [PMID: 12891217]

Meineke V et al: Medical management principles for radiation

accidents. Mil Med 2003;168:219–22. [PMID: 12685687]

Turai I et al: Medical response to radiation incidents and nuclear

threats. Br Med J 2004;328:568–72.

802

00

PHYSIOLOGIC ADAPTATION TO PREGNANCY

The average duration of gestation is 40 weeks from the first

day of the last menses, with term defined as being between

37 and 42 weeks. The mother’s basic physiology is altered in

a number of ways during normal pregnancy. Some of these

may alter her baseline state and response to critical illness,

but others may predispose to injuries and conditions that

require critical care.

Cardiovascular System

Pregnancy causes changes in the appearance and function of

the heart and great vessels. Elevation of the hemidiaphragms,

which accompanies advancing pregnancy, causes the heart to

assume a more horizontal position in the chest, and this

results in lateral deviation of the cardiac apex, with a larger

cardiac silhouette on chest x-ray and a shift in the electrical

axis. The heart does increase in size in pregnancy, but only by

about 12%. Cardiac output increases by 30–50%, with most

of the increase occurring in the first trimester. Both stroke

volume and heart rate increase. The heart rate increases by

about 17%, with the maximum reached by the middle of the

third trimester (32 weeks). Stroke volume increases by 32%,

with the maximum reached by midgestation. After 20 weeks,

cardiac output may decrease significantly (25–30%) when the

patient lies in the supine position as compared with the left

lateral position. This is apparently due to compression of the

inferior vena cava by the pregnant uterus with resulting

decreased venous return. The distribution of cardiac output is

altered as well. At term, 17% of the cardiac output is directed

to the uterus and its contents, and an additional 2% goes to

the breasts. The skin and kidneys also receive additional blood

flow compared with the nonpregnant state. Blood flow to the

brain and liver may increase. Perfusion of other organs such

as the skeletal muscle and gut is unchanged.

Peripheral vascular resistance decreases during preg-

nancy. A concomitant decrease in systemic blood pressure

reaches its nadir at about 24 weeks of gestation. Blood pressure

then rises gradually until term but should not exceed non-

pregnant levels at any time during pregnancy. Central hemo-

dynamic studies of normal pregnant women demonstrate a

significant decrease in both systemic and pulmonary vascu-

lar resistance. Mean arterial pressure, pulmonary capillary

wedge pressure, central venous pressure, and left ventricular

stroke work index are unchanged. Colloid osmotic pressure

is decreased.

Labor and delivery are associated with cardiac stress

beyond that of late pregnancy. Cardiac output may increase

by as much as 40% in patients not receiving adequate pain

relief, although those with adequate anesthesia experience

much smaller rises. The rise in cardiac output is progressive

over the different stages of labor, and there is a further rise

of approximately 15% during each uterine contraction

resulting from the expression of 300–500 mL of blood from

the uterus back into the mother’s circulation. Delivery of

the fetus is associated with as much as a 59% increase in

cardiac output, presumably as a result of autotransfusion of

blood contained in the uterus. This increase may be blunted

by the blood loss at delivery. In patients with clinically sig-

nificant mitral stenosis, delivery may be associated with an

increase in the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of up to

16 mm Hg.

Respiratory System

During pregnancy, the subcostal angle increases from about

68 degrees to about 103 degrees, with a concomitant increase

in the transthoracic diameter. The resting level of the

diaphragm is 4 cm higher at term than in the nongravid

state. Many authors state that this elevation is a result of pres-

sure from the expanding uterus. However, diaphragmatic

excursions are increased by 1–2 cm over nonpregnant values,

suggesting that uterine pressure is not the sole cause of the

elevation.

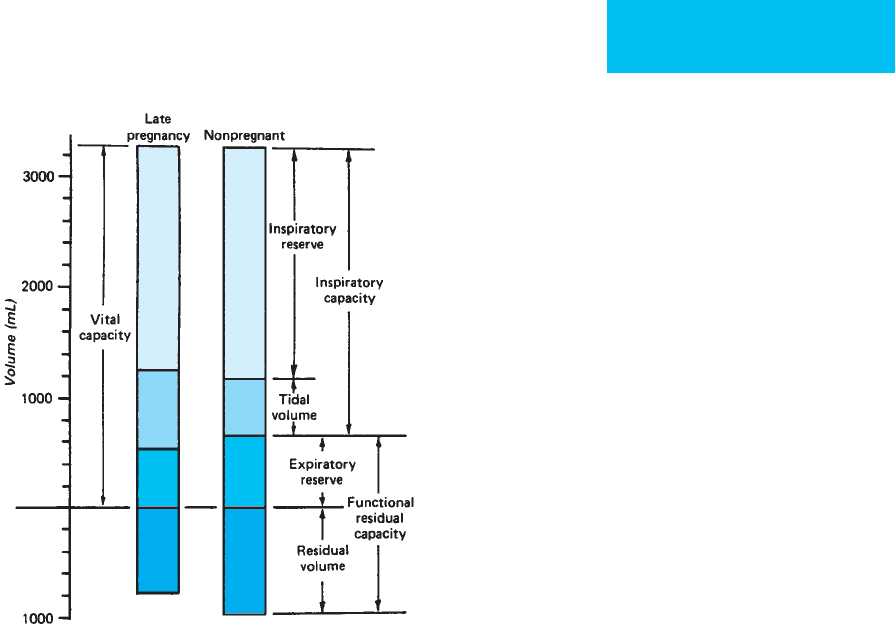

Several aspects of pulmonary function change during

pregnancy (Figure 38–1). Tidal volume increases by about

40%, and residual volume decreases by about 20%. These

38

Critical Care Issues

in Pregnancy

Marie H. Beall, MD

Andrea T. Jelks, MD

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CRITICAL CARE ISSUES IN PREGNANCY

803

changes may make the lung appear denser on x-ray because

it is more collapsed during expiration. Data on vital capacity

in pregnancy are contradictory, with older studies suggesting

that there is no change and some newer ones suggesting that

there is a marked increase. During pregnancy, expiratory

reserve volume decreases by about 200 mL, and inspiratory

reserve volume increases by about 300 mL. Forced expiratory

volume appears to be unchanged.

Total body oxygen uptake at rest increases by about

30–40 mL/min in pregnancy, or about 12–20%. Most of the

oxygen is needed to meet maternal metabolic alterations.

The increased oxygen need is met by increased tidal vol-

ume alone because the pulmonary diffusing capacity

appears to be decreased in pregnancy, and the respiratory

rate does not significantly increase. There is a total increase

in minute ventilation of 48% at term, which exceeds the

need for increased oxygen delivery. This “hyperventilation

of pregnancy” appears to be hormonally mediated and

results in a decrease in Pa

CO

2

to below 30 mm Hg in normal

women. Maternal pH does not change because there is a

reciprocal decline in bicarbonate concentration. The net

result of these acid-base alterations is facilitation of fetal-

maternal CO

2

exchange.

Hematologic System

Both the volume and the composition of the blood change

during pregnancy. Plasma volume increases by 40–60%, the

bulk of the increase occurring before the beginning of the

third trimester. The red blood cell mass also expands, with a

total increase of 25% at term. This percentage can be maxi-

mized (to about 30%) by iron supplementation. An increase

in red blood cell mass occurs throughout pregnancy, but the

early—and in some patients disproportionate—increase in

plasma volume leads to a dilutional anemia. Normal preg-

nant women who are not iron-supplemented have hemoglo-

bin concentrations of approximately 11 g/dL at 24 weeks of

gestation, with little change until term. Those supplemented

with iron have similar hemoglobin concentrations at 24 weeks

but manifest an increase in hemoglobin to near-normal at

term.

The white blood cell count increases to about 10,000/μL at

term. The platelet count may decrease slightly to a mean value

of 260,000/μL at 35 weeks of gestation. Platelet levels above

120,000/μL generally are regarded as normal in pregnancy.

Biochemical characteristics of the blood also change.

Serum osmolarity decreases by about 10 mOsm/L early in

pregnancy and remains constant thereafter. Sodium, potas-

sium, calcium, magnesium, and zinc all demonstrate minor

decreases in their serum levels. Chloride does not change,

although bicarbonate decreases markedly. Serum creatinine

decreases early, with a mean creatinine of 0.66 mg/dL at

12 weeks, and this decrease is maintained at least until 32 weeks

of gestation. The creatinine clearance in pregnancy is

approximately 50% higher than in the nonpregnant state.

The plasma concentrations of albumin and total protein

decrease in proportion to the plasma volume expansion.

Most of the commonly tested serum enzymes do not change

in pregnancy, but alkaline phosphatase does increase as a

result of the production of a placental form of this enzyme.

Creatine kinase decreases in early pregnancy, although the

serum levels return to normal by term. Serum lipids increase

toward term, with the levels of cholesterol and triglycerides

doubling during pregnancy.

The levels of many coagulation factors are altered.

Fibrinogen increases to levels as high as 600 mg/dL at term,

with levels below 400 mg/dL generally being regarded as

unusual. The presence of fibrin degradation products in trace

amounts is also not unusual at term and depends on the sensi-

tivity of the test being used. Coagulation and bleeding times are

not increased. The risk of thromboembolism increases, with a

relative risk of 1.8 in gestation and 5.5 during the puerperium.

The increased risk of thromboembolism also may be due to the

increased incidence of venous stasis and vessel wall injury.

Immune System

Pregnant women appear to be at increased risk of certain

infections, probably owing to the same immune alterations

that allow tolerance of the antigenically foreign placenta. For

Figure 38–1. The components of lung volume in late

pregnancy compared with those in nonpregnant women.

(Reproduced, with permission, from Hytten FE, Leitch I: The

Physiology of Human Pregnancy. Boston: Blackwell, 1964.)

CHAPTER 38

804

this reason, reactivation of viral diseases and tuberculosis are

more common during pregnancy. Severe complications of

common disorders such as varicella and pyelonephritis are

also more frequent. Measurable indices of immune function

such as white blood cell counts and immunoglobulin levels

do not explain the maternal immune dysfunction. Various

theories have been offered to explain these observations, but

none has achieved general acceptance.

Granger JP: Maternal and fetal adaptations during pregnancy: Lessons

in regulatory and integrative physiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr

Comp Physiol 2002;283:R1289–92. [PMID: 12429557]

Yeomans ER, Gilstrap LC 3

rd

: Physiologic changes in pregnancy

and their impact on critical care. Crit Care Med 2005;33:

S256–8. [PMID: 16215345]

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE CARE

OF THE PREGNANT PATIENT IN THE ICU

The care of the pregnant patient is necessarily the care of two

patients. Although care of the mother is the primary concern

in most circumstances, attention also must be paid to fetal

health and well-being.

Position

As discussed earlier, a pregnant woman may experience a

decrease in cardiac output with associated hypotension when

lying in the supine position. For this reason, the pregnant

woman who is beyond the twentieth week of gestation

should avoid lying supine. In the ICU, this means that preg-

nant women who are bedridden and unable to move by

themselves should be positioned with the right hip elevated,

usually with an obstetric wedge, to about 4 in above the plane

of the bed. Alternatively, the patient may be positioned in the

right lateral decubitus position, taking care that she is tilted

adequately to prevent caval compression. This is not neces-

sary in a patient who is in Fowler’s position, that is, with the

head of the bed elevated. Because of the increased risk of

thromboembolism in pregnancy or immediately postpar-

tum, these patients also should receive measures to prevent

deep venous thrombosis. Venous compression stockings may

be of some benefit, but—especially in the recently delivered

patient—heparin in doses adequate to achieve a partial

thromboplastin time (PTT) of 65–85 s or low molecular

weight heparin sufficient to achieve anti–factor Xa levels of

0.05–0.2 units/mL is considered necessary to avoid pelvic or

lower extremity venous thrombosis.

Monitoring

When caring for a critically ill pregnant patient, the question

of how to monitor the fetus arises frequently. Monitoring by

auscultation of fetal heart tones is considered one of the vital

signs in any hospitalized pregnant women. However, contin-

uous fetal heart rate monitoring with an electronic monitor

may be indicated in the viable or near-viable fetus (23 weeks

and beyond), especially if the maternal condition affects pul-

monary or hemodynamic function. Use of the continuous

fetal monitor requires personnel skilled in its interpretation.

Fetal monitoring may be especially helpful during special

procedures or surgery when maternal position, hypotension,

or anesthesia can lead to fetal compromise that could be

reversed with changes in position or fluid resuscitation. Fetal

heart rate monitoring according to a predetermined schedule

(nonstress testing) also may be useful in gauging fetal

response to the mother’s illness and in determining when

fetal compromise may necessitate early delivery. This strategy

(as opposed to continuous fetal heart rate monitoring)

should be reserved for the stable patient whose underlying

condition might result in decreased uteroplacental perfusion

or altered placental function. Additional biophysical testing

might be deemed necessary by the consulting obstetrician,

but that subject is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Teratogenesis and Drugs Used During Pregnancy

Critical care of a pregnant patient necessarily involves the use

of drugs and physical agents that may have an effect on the

developing fetus. The first concern of the physician is properly

with the life and long-term health of the mother. In cases in

which alternative therapies or diagnostic modalities are avail-

able, the physician must consider their possible fetal effects.

Information regarding the potential risk to the fetus of

various agents is available from a number of published

sources and from the manufacturers’ package inserts. In

addition, many areas are served by teratogen “hotline” serv-

ices. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all

drug manufacturers to rate their drugs for risk in pregnancy

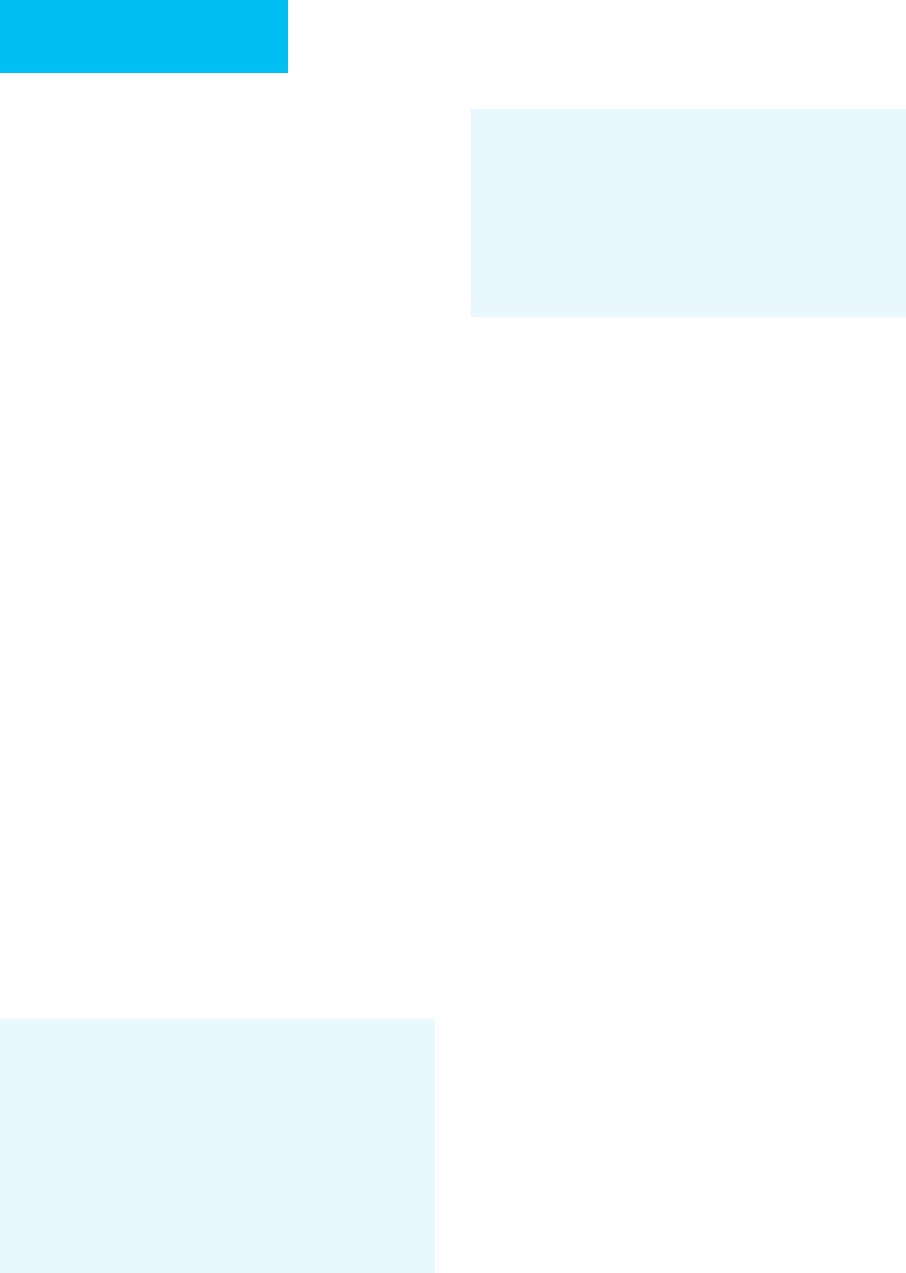

(Table 38–1). Most drugs are not studied in pregnancy dur-

ing the FDA approval period, so most new drugs will be

placed in category C. For this reason, many drugs used rou-

tinely during pregnancy are older ones, with an established

record of safe use.

The overriding principle in choice of a therapeutic agent

is that the anticipated benefit should outweigh any theoretic

risks. Consequently, a potentially teratogenic—but life-

sustaining—pharmacologic intervention for which there is

no good alternative would be acceptable, whereas one with

less proven risk but prescribed as a comfort measure only

might not be.

Imaging Studies

Ionizing radiation is known to be a human teratogen, and the

use of x-ray is appropriately limited in pregnant women.

Persons exposed to high levels of ionizing radiation in utero

may exhibit microcephaly, mental retardation, retarded

growth, and various structural abnormalities. Some reports

also have suggested an increased risk of childhood cancer fol-

lowing prenatal x-ray exposure. Data from atomic bomb sur-

vivors suggest that the most vulnerable period for the fetus is

from 8–15 weeks of gestation. Fetuses in this gestational age

CRITICAL CARE ISSUES IN PREGNANCY

805

range appear to have a linear increase in mental retardation

with increasing x-ray exposure, with an incidence of 0.4% per

rad of exposure, although a definite fetal effect may not be

seen below 5 cGy. Fetuses older than 16 weeks were less sensi-

tive to x-rays. In one study, the risk of childhood leukemia was

estimated to be 1.7 times that of controls in patients exposed

to radiation in utero. The risk for childhood cancers also

appeared to be higher in fetuses exposed to x-rays in the sec-

ond as compared with the third trimester. The fetal exposure

for different radiologic studies has been calculated and is pre-

sented in Table 38–2. As will be apparent, many studies, such

as chest films and head and neck studies, entail only slight

exposure of the fetus, although the fetal exposure owing to

abdominopelvic CT studies is appreciable. Nevertheless, the

uterus and its contents should be shielded whenever possible.

Iodinated contrast media are not contraindicated in preg-

nancy and may be used as in nonpregnant patients. These

media may be rated in category D owing to the risk of fetal

goiter when these agents are injected into the amniotic fluid.

Radionuclide scans should be used with caution in preg-

nancy. Iodine is concentrated in the fetal thyroid after 10 weeks

of gestation, and radioactive iodine may cause harm to the fetal

thyroid. Other radionuclides may be associated with an

increased risk of fetal mutagenesis or teratogenesis if they cross

the placenta in large amounts. Agents bound to large protein

aggregates do not cross the placenta and probably represent a

negligible risk to the fetus. In particular, the performance of

pulmonary ventilation-perfusion scanning for pulmonary

emboli has been calculated to result in a fetal dose of only

50 mrem, and this is largely from fetal exposure to the agent in

the maternal bladder during urinary excretion of the agent.

Ultrasonography is used extensively in obstetrics.

Controlled studies are not available regarding its safety, but

numerous observational studies have lead to the conclusion

that diagnostic ultrasound is safe for use in pregnancy.

However, fetal damage has been demonstrated in animal

models using ultrasound power levels sufficient to cause tis-

sue heating. For this reason, the use of therapeutic ultra-

sound in pregnancy is contraindicated. Few studies are

available concerning the safety of MRI in pregnancy. There is

a theoretical concern that the strong magnetic field may

affect fetal cell migration in the first trimester, and the use of

MRI has been discouraged early in pregnancy, although there

are no reports of adverse human fetal effects.

Total Parenteral Nutrition

As a consequence of depletion of maternal glucose by the

fetoplacental unit, pregnant patients are more sensitive than

Category A Controlled studies in women fail to demonstrate a

risk to the fetus in the first trimester (and there is no

evidence of risk in later trimesters), and the possibil-

ity of fetal harm appears remote.

Category B Either animal-reproduction studies have not demon-

strated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies

in pregnant women, or animal-reproduction studies

have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease

in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled

studies in women in the first trimester (and there is

no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

Category C Either studies in animals have revealed adverse

effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal or

other) and there are no controlled studies in women,

or studies in women and animals are not available.

Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit

justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Category D There is positive evidence of human fetal risk, but the

benefits from use in pregnant women may be accept-

able despite the risk (eg, if the drug is needed in a

life-threatening situation or for a serious disease for

which safer drugs cannot be used or are ineffective).

Category X Studies in animals or human beings have demon-

strated fetal abnormalities, or there is evidence of

fetal risk based on human experience, or both, and

the risk of the drug in pregnant women clearly out-

weighs any possible benefit. The drug is contraindi-

cated in women who are or may become pregnant.

Federal Register 1980;44:31434–67.

Table 38–1. Risk factors for drug use in pregnancy.

Absorbed Dose

Examination Mrad mGy

Upper GI series 100 1

Cholecystography 100 1

Lumbar spine radiography 400 4

Pelvic radiography 200 2

Hip and femur radiography 300 3

Retrograde pyelography 600 6

Barium enema study 1000 10

Abdominal (KUB) radiography 250 2.5

Hysterosalpingography 150 10

CT scan, head ~0 ~0

CT scan, chest 16 0.16

CT scan, abdomen 3000 30

Data from Parry RA, Glaze SA, Archer BR: The AAPM/RSNA Physics

Tutorial for Residents. RadioGraphics 1999;19:1289–1302.

Table 38–2. Estimated doses to the uterus from diagnostic

procedures.

CHAPTER 38

806

nonpregnant ones to starvation. Blood glucose is lower by

15–20 mg/dL in a pregnant woman after a 12-hour fast, and

starvation ketosis is exaggerated. Undernutrition has been

associated with increased infant mortality and decreased

birth weight. These facts suggest that nutrition should be

addressed early in the course of critical care. Total parenteral

nutrition has been used in pregnancy with good fetal out-

comes in patients with intractable nausea and vomiting of

pregnancy as well as in patients with other chronic diseases.

Total parenteral nutrition should be considered in any preg-

nant patient who is expected to be without oral intake for

more than 7 days and in whom enteral (tube) feedings are

contraindicated. In patients in whom shorter durations of

starvation are expected, peripheral nutritional supplementa-

tion is essential. At a minimum, when the patient is denied

oral intake, enough intravenous glucose should be adminis-

tered to avoid ketonemia.

Patient Counseling

The fetal organs are essentially fully formed by the end of the

first trimester. This is important when considering the ter-

atogenic potential of medications given to the mother.

Teratogenic effects are most likely to occur early, when preg-

nancy may not yet be diagnosed. CNS growth and develop-

ment, body growth, and sexual organ development occur in

the second trimester, with CNS development and body

growth continuing during the third trimester. Drugs given

during the last trimester may affect neurologic development

but will not cause significant structural abnormalities other

than impaired fetal growth. A woman in the ICU who is

found to be pregnant should be given complete information

on the timing and dosages of the drugs and diagnostic agents

used in her care. It may be helpful to refer such a patient and

her family to a medical geneticist or prenatal diagnostic cen-

ter for counseling and possible diagnostic procedures. As a

medicolegal issue, it also may be advisable to obtain an

obstetric ultrasound examination as early as possible during

the pregnant patient’s stay in the ICU. Fetal abnormalities

apparent at that time are probably preexisting conditions

and not the result of medications given in the unit.

Furthermore, this will document gestational age and estab-

lish a baseline from which to assess fetal growth.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice: ACOG Committee

Opinion. Number 299, September 2004. Guidelines for diagnos-

tic imaging during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104: 647–51.

[PMID: 15339791]

Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ: Drugs in Pregnancy and

Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk, 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

De Santis M et al: Ionizing radiations in pregnancy and teratogen-

esis: A review of literature. Reprod Toxicol 2005;20:323–9. [PMID:

15925481]

Fattibene P et al: Prenatal exposure to ionizing radiation: Sources,

effects and regulatory aspects. Acta Pediatr 1999;88:693–702.

[PMID: 10447122]

McNally RJ, Parker L: Environmental factors and childhood acute

leukemias and lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:583–98.

[PMID: 16690516]

Shepard TH, Lemore RJ: Catalog of Teratogenic Agents, 11th ed.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Soubra SH, Guntupalli KK: Critical illness in pregnancy: An

overview. Crit Care Med 2005;33:S248–55. [PMID: 16215344]

Vasquez DN et al: Clinical characteristics and outcomes of obstet-

ric patients requiring ICU admission. Chest 2007;131:718–24.

[PMID: 17356085]

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

in the Pregnant Woman

The American Heart Association has recommended that

when cardiac arrest occurs in a pregnant woman, standard

resuscitative measures and procedures can and should be

taken without modification. In particular, they endorse the

use of closed-chest compression, defibrillation, and vaso-

pressors as indicated and emphasize the need to displace the

uterus from the abdominal vessels by a right hip wedge or by

manual pressure on the fundus. Finally, they endorse the per-

formance of a perimortem cesarean section promptly if rou-

tine ACLS protocols are ineffective in restoring circulation

(see below).

Labor and Delivery in the ICU

The presence of a pregnant woman in the ICU necessitates a

plan for delivery of the pregnancy, if necessary. On occasion,

spontaneous labor may occur in a patient too unstable to be

transferred to the delivery room. In this case, labor and deliv-

ery must be undertaken in the ICU. Fetal heart rate monitor-

ing may be useful in advising the pediatrician about the fetal

condition even if cesarean section is not an option. Attention

should be paid to achieving adequate maternal analgesia

because of the significant maternal cardiac demands

imposed by unmedicated labor. In the case of any fetus of

22 weeks or more of gestational age or expected to weigh

more than 500 g, a neonatal resuscitation team should be in

attendance at delivery. The delivery should be conducted by

experienced personnel in an atraumatic manner.

Rarely, it may be necessary to perform perimortem

cesarean section in the ICU if the mother has died and an

attempt is being made to salvage the fetus. For this reason, in

any critically ill hospitalized pregnant patient, a determina-

tion should be made as early as possible about the potential

viability of the fetus. If perimortem cesarean section is a pos-

sibility, necessary instruments should be kept at or near the

bedside. In a large series of such procedures, normal infant

survival was associated with delivery within 5 minutes of

maternal death (from cardiac arrest). Fewer than 15% of

infants survived when delivery was performed more than

15 minutes after maternal demise, although fetal survival

after a much longer delay has been reported. Given this infor-

mation and data suggesting that the effectiveness of CPR in