Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

827

UFH is effective for prevention and treatment of VTE

(DVT and PE; Table 39-4), mural thrombus after myocardial

infarction, unstable angina, and acute myocardial infarction.

UFH is usually combined with antiplatelet agents (eg,

aspirin, clopidogrel, and more recently, GP IIb/IIIa receptor

inhibitors) in the treatment of acute ischemic heart disease.

UFH has been used in conjunction with thrombolysis for

coronary artery occlusion; however, recent studies have sug-

gested that UFH may increase the risk of bleeding with little

added benefit over thrombolysis, particularly in patients

receiving aspirin. UFH is used alone or in combination with

GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors during percutaneous coronary inter-

vention (PCI). UFH is not effective for prevention of

restenosis after coronary angioplasty, and prolonged infusion

of UFH after completion of PCI increases bleeding without

reducing ischemic events. Guidelines for use of UFH in coro-

nary artery disease have been proposed (see Table 39–4);

however, ongoing trials probably will result in modification

of these guidelines as results of studies using newer agents

and combinations of agents are reported. UFH is also used

during extracorporeal circulation of blood (in cardiovascular

surgery and hemodialysis), prior to cardioversion in atrial

fibrillation (if no mural thrombus is detected by trans-

esophageal echocardiography), in some cases of dissemi-

nated intravascular coagulation, and to treat fetal growth

retardation in pregnant women. Heparin (UFH or low-

molecular-weight heparin) is generally the anticoagulant of

choice during pregnancy because it does not cross the pla-

centa and is not teratogenic. Heparin is also used when

chronic oral anticoagulation (eg, in patients with heart

valves, atrial fibrillation, and recurrent thromboembolic dis-

ease) is interrupted for invasive procedures or when recur-

rent thromboembolism occurs despite adequate oral

anticoagulation.

Multiple factors modify the anticoagulant effects of UFH

(Table 39–5), so the precise dose of UFH in a given patient

cannot be predicted in advance. When immediate anticoag-

ulation is required, an intravenous bolus is given followed by

continuous intravenous infusion or intermittent subcuta-

neous UFH (see Table 39–3). Continuous infusion is used

more often because of its lower risk of hemorrhage, but inter-

mittent subcutaneous UFH may be used in selected situations

(eg, thromboprophylaxis). Long-term use of subcutaneous

UFH during pregnancy or other conditions requiring long-

term outpatient heparin therapy has been replaced with sub-

cutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin. Careful monitoring

of the aPTT is essential for patients maintained on UFH to

ensure adequate anticoagulant effect without undue risk of

hemorrhage (see Table 39–3). Larger doses of UFH are

required to treat established thromboembolic disease than for

prevention of VTE possibly because thrombin bound to fibrin is

much less sensitive to inhibition by UFH than circulating throm-

bin and because of increased plasma reactive proteins, which

bind and neutralize UFH. Heparin resistance (requirement of

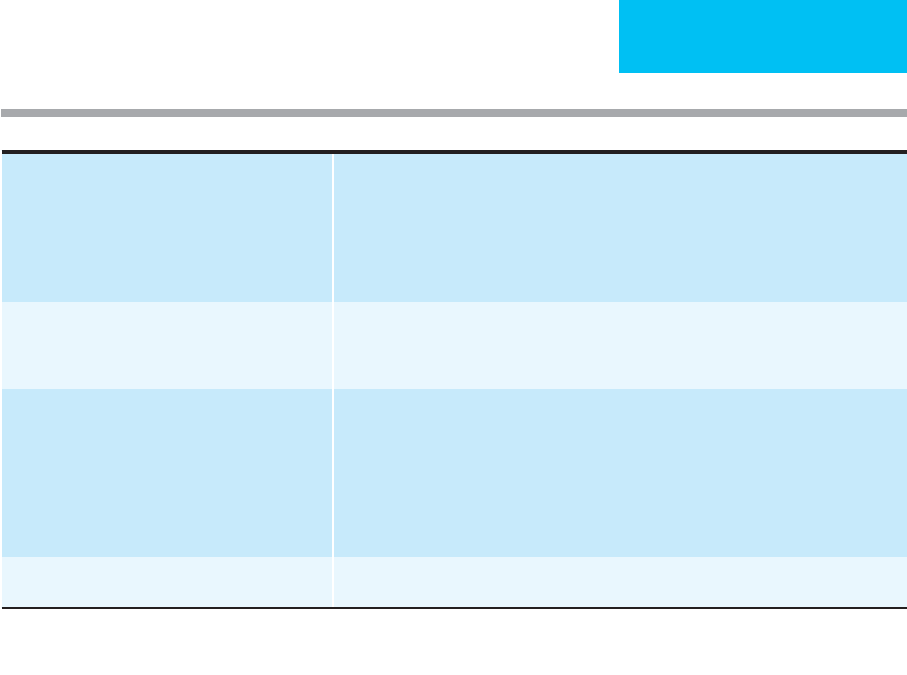

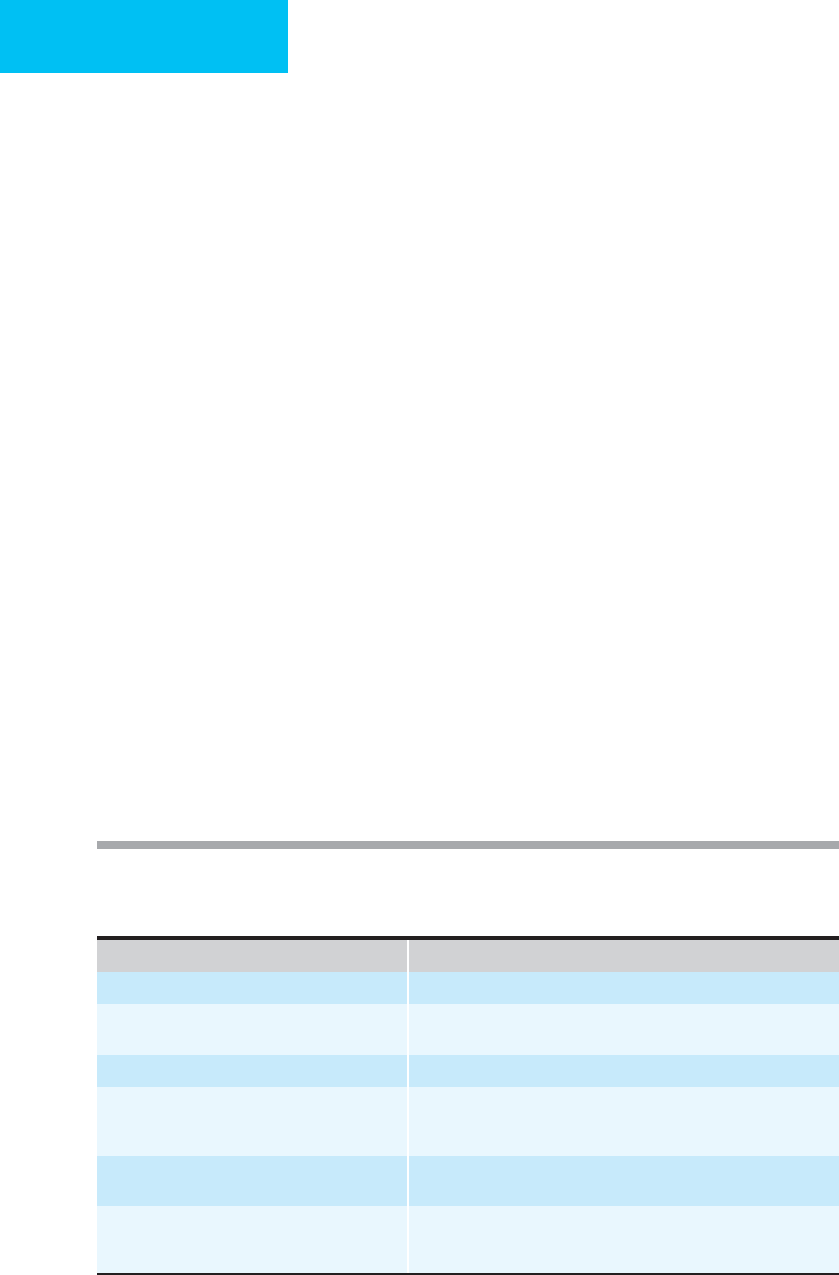

Table 39–4. Indications and administration of anticoagulants in selected settings.

∗

Prevention of venous thromboembolism Low risk (patients <40 with no risk factors undergoing minor surgery): early mobilization.

Moderate risk (<40 with risk factors for VTE or patients age 40–60): UFH every 12 hours, LMWH

(<3400 units/day), IPC.

High risk (patient >60, 40–60 with risk factors): UFH every 8 hours, LMWH (>3400 units/day), or IPC.

Highest risk (multiple risk factors, hip or knee arthroplasty, hip fracture surgery, major trauma,

spinal cord injury): LMWH (>3400 units/day), fondaparinux, oral anticoagulant (INR 2–3), or

IPC combined with UFH every 12 hours or LMWH daily.

Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism Adjusted-dose UFH. Monitor and adjust according to Table 39–3; OR full-dose LMWH (dose varies

by preparation). Begin oral anticoagulation on day 1. Continue UFH or LMWH until fully

anticoagulated with oral agent (overlap with oral anticoagulant in therapeutic range at least

2 days, usually 4–5 days total heparin).

Coronary artery disease (if no contraindication to

anticoagulation)

Non-ST-segment acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI). Use UFH in combination with antiplatelet

therapy. Dose as in Table 39-3, target aPTT between 50 and 75 seconds

†

or LMWH (dose varies

with preparation.

Acute MI with ST-segment elevation (STEMI) or new left bundle branch. Use UFH in combination with

fibrinolytic: Dose as in Table 39–3, target aPTT between 50 and 75 seconds, administer for 48

hours (longer in patients at high risk for systemic or venous thromboembolism—anterior MI,

pump failure, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus, previous thromboembolism) or LMWH

(dose varies with preparation).

Chronic outpatient use (pregnancy,

warfarin failure)

∗

UFH at 12,000 units SC twice daily. Monitor aPTT 6 hours after injection and adjust subsequent

dose to maintain aPTT 50–85 seconds if LMWH is unavailable.

∗

Choice of specific regimen should take into account individual patient characteristics, including risk of thrombosis, risk of bleeding with

anticoagulation and renal function.

†

7th ACCP Conference Guidelines

CHAPTER 39

828

very large doses of heparin to prolong the aPTT) may occur

owing to the presence of elevated factor VIII or fibrinogen

levels, increased heparin-binding proteins, increased

heparin clearance, or AT deficiency. Measuring anti–factor

Xa levels may be a better alternative for monitoring heparin

therapy in these patients. It is not necessary to cause prolon-

gation of the aPTT for prevention of VTE in moderate-risk

patients, although in very high-risk patients—for example,

those undergoing orthopedic surgery—prolongation of the

aPTT to the upper end of normal is required to prevent

thrombosis.

Hemorrhage is the most common complication of

heparin therapy. Hemorrhage occurs more frequently with

high-dose heparin therapy and when the aPTT is prolonged

beyond the therapeutic range. Intermittent bolus UFH

results in a higher rate of hemorrhage than continuous-

infusion UFH, which may be due to the higher total daily

dose required to maintain a therapeutic aPTT with intermit-

tent administration. Concomitant use of aspirin or other

antiplatelet drugs increases the risk of hemorrhage, but in

patients with coronary thrombosis, the risk is felt to be

acceptable. The presence of other hemostatic defects, chronic

alcoholism, and the overall general condition of the patient

also influence the risk of hemorrhage with heparin therapy.

Management of hemorrhage associated with UFH varies

depending on the severity of the bleeding and the degree of

the anticoagulant effect, as measured by the aPTT. If the indi-

cation for anticoagulation is strong, continuation of UFH

with close monitoring of the aPTT and blood counts may be

acceptable for patients with trivial bleeding. If minor bleed-

ing is associated with an aPTT that is markedly prolonged

above the therapeutic range, withholding UFH until the

aPTT falls into the desired range (usually within a few hours)

is recommended if the patient is stable, with clinical evalua-

tion of the patient before resuming UFH for evidence of con-

tinued hemorrhage. Serious bleeding requires cessation of

UFH therapy, whereas truly life-threatening bleeding (eg,

intracranial hemorrhage or hemorrhage associated with

hemodynamic instability) may require immediate reversal of

UFH with protamine sulfate. One milligram of protamine

sulfate per 100 units of UFH (50 mg protamine sulfate for a

5000-unit dose of UFH), given intravenously over 10 minutes

(to avoid hypotension), will neutralize UFH given 30 minutes

earlier. The dose of protamine sulfate should be reduced

depending on the time interval from UFH administration

(eg, give 50% of the dose if 60 minutes have elapsed and 25%

if 2 hours have elapsed), and for reversal of continuous-

infusion UFH, the dose of protamine sulfate should be esti-

mated based on the UFH infused in the preceding 2–3 hours.

Since protamine sulfate has a shorter half-life than UFH,

the dose may need to be repeated. Side effects of prota-

mine sulfate include hypotension with rapid administra-

tion and prolongation of the aPTT (with possible bleeding)

if excess protamine is given. Recombinant platelet factor

4 (2.5–5 mg/kg) has been reported to be effective for reversal

of UFH as well but is not available everywhere.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) occurs com-

monly (5–15%) with therapeutic UFH administration, less

commonly with prophylactic UFH, and appears to be more

common with UFH derived from bovine lung than that from

porcine intestine. The onset of thrombocytopenia is usually

between 3 and 15 days after initiation of treatment with UFH

(median 10 days) but may be as short as a few hours in a pre-

viously sensitized individual, particularly if the prior treat-

ment with UFH was within 3 months of reexposure.

Resolution of thrombocytopenia occurs within 4–5 days of

discontinuation of UFH.

Thrombocytopenia in this disorder is immunologically

mediated. Heparin molecules greater than MW 4000 bind to

platelet factor 4 and form complexes to which heparin-

induced antibodies bind. Platelets are activated, resulting in

increased thrombin generation. Thrombosis, usually associ-

ated with very severe thrombocytopenia, occurs in about

0.4% of patients.

Diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds, but sero-

logic tests are available to confirm the presence of HIT anti-

bodies. Although these tests are sensitive for the presence of

HIT antibodies, they are less specific and therefore must be

interpreted with caution. Prevention of this disorder by

shortening the duration of UFH administration is impor-

tant. Initiation of oral anticoagulants simultaneously with

UFH in patients who will require long-term anticoagulation

will permit a shorter course of UFH and is highly recom-

mended for patients requiring long-term anticoagulation.

Frequent (every 1–2 days) monitoring of the platelet count is

important for identification of patients before thrombosis

occurs. The use of low-molecular-weight heparin (or hepari-

noids) appears to be associated with a lower risk of heparin-

induced thrombocytopenia as well.

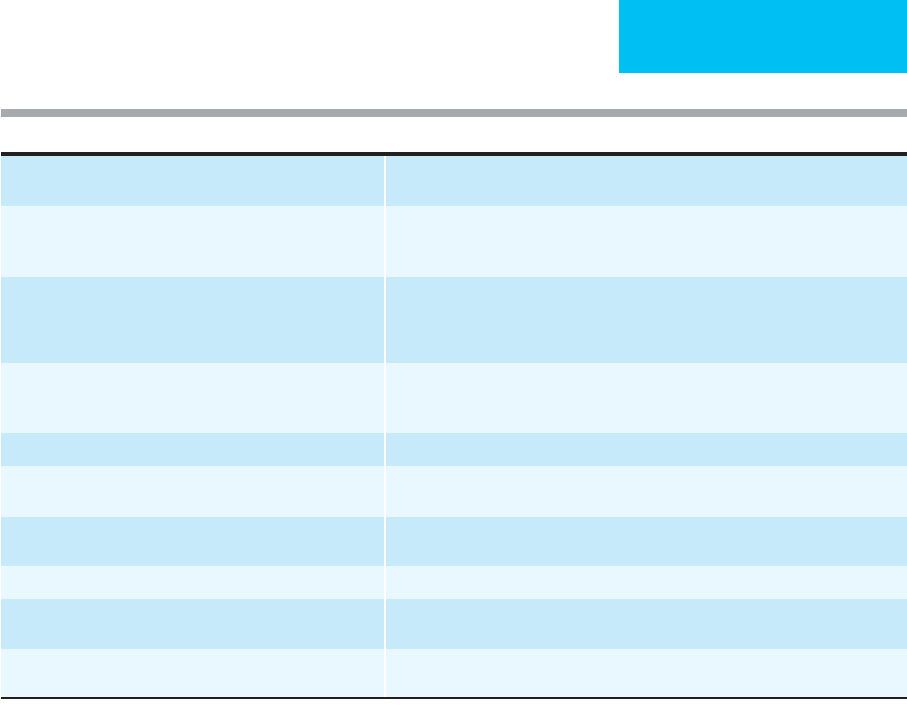

Management of HIT is outlined in Table 39–6. Stopping

UFH is the most common intervention, but there appears to

be a marked risk in clinically significant thrombosis in the

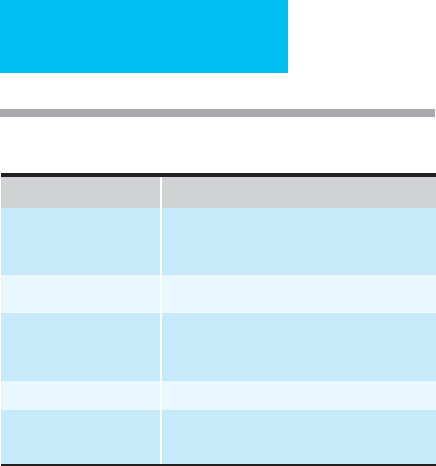

Table 39–5. Endogenous factors modifying the

anticoagulant effect of heparin.

Factor Mechanism

Platelets Bind and protect factor Xa from heparin.

Produce platelet factor 4 and neutralizes

heparin.

Fibrin Binds thrombin and protects if from heparin.

Endothelial surfaces Bind thrombin and protects it from heparin.

Bind and neutralize heparin via displaced

platelet factor 4.

Plasma proteins Bind and neutralize heparin.

Antithrombin

(antithrombin III)

Hereditary or acquired deficiency state results

in heparin resistance.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

829

week after cessation of UFH. Warfarin may aggravate throm-

bosis and should be delayed until the platelet count is over

100,000/μL. There are two anticoagulants currently approved

in the United States for use in HIT—lepirudin (a recombi-

nant hirudin) and argatroban (a selective direct thrombin

inhibitor)—that should be considered even without overt

thrombosis. Bivalirudin (another hirudin analogue), which

is approved in the United States as an alternative to heparin

in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions,

appears to be promising, and because it has only minor renal

excretion, it may be preferable to lepirudin in patients with

significant renal impairment. Anticoagulation with the alter-

native agent should be continued until the platelet count has

returned to normal. Ancrod also has been used for treatment

of HIT but is not available in the United States.

If anticoagulant therapy is necessary in a patient with a

suspected history of HIT (without complicating thrombo-

sis), heparin-dependent antibodies (platelet activation assay

or antigen assay) may help to determine the risk of reexpo-

sure to heparin. If negative, short-term treatment with UFH

with careful monitoring may be acceptable. Patients with a

history of HIT-associated thrombosis should be considered

for treatment with anticoagulants other than heparin.

Other adverse effects of UFH include transient elevation of

liver function tests (particularly ALT and AST), hyperkalemia,

osteoporosis (owing to heparin binding to osteoblasts that

release factors that stimulate osteoclasts; clinically significant

with long-term UFH administration), skin necrosis, alopecia,

hypersensitivity reactions, and hypoaldosteronism.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparins (LMWHs)

LMWHs are prepared by depolymerization of UFH by

chemical or enzymatic means. Like UFH, LMWH accelerates

antithrombin-mediated inactivation of factor Xa, but unlike

UFH, LMWH does not inactivate thrombin because it lacks

the additional 13 saccharides required for heparin to form a

complex with AT. Because it binds less strongly to plasma

proteins, cells, and thrombin, LMWH has greater bioavail-

ability at low doses, a longer half-life, and a more predictable

anticoagulant response than UFH. LMWH can be adminis-

tered subcutaneously at a fixed dose (adjusted for weight)

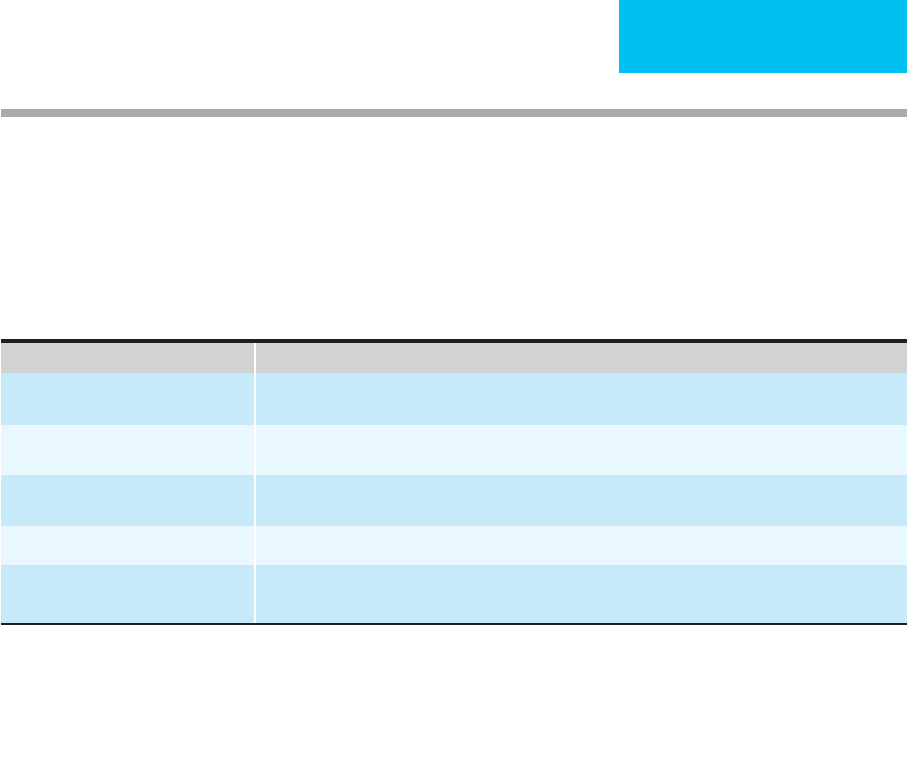

1. Monitor platelet counts during heparin therapy every 1–2 days.

2. Exclude other causes of acute thrombocytopenia (other drugs, sepsis, DIC, pseudothrombocytopenia).

3. Evaluate for thrombotic complications (iliofemoral artery occlusion, cerebral infarction, and myocardial infarctions are the most common; other

arterial thromboses and venous thromboses occur less commonly).

4. Do not administer platelet tranfusions (increased risk of thrombosis).

5. Discontinue heparin (including heparin flushes) for platelet count below 100,000/uL.

6. Administered alternative anticoagulant until the platelet count has recovered and oral anticoagulation has taken effect, if long-term anticoagulation

is required. Overlap alternative anticoagulant with warfarin for a minimum of 5 days.

∗

7. Consider lower extremity ultrasound to assess for subclinical thrombosis.

Anticoagulant Dose/Monitoring

Lepirudin (a recombinant hirudin

derivative)

0.4 mg/kg (up to 44 mg) IV bolus followed by 0.15 mg/kg/h. Adjust dose to maintain aPTT 1.5–2.5 times

normal range. May omit bolus in patients with renal failure.

Danaparoid (a heparinoid, available

outside the United States)

2250 units IV bolus followed by 400 units/h for 4 hours, then 300 units/h for 4 hours, then 150–250

units/h. Monitor anti-factor Xa activity (if available), maintain at 0.5–0.8 anti-factor Xa units/mL

Argatroban (a selective direct thrombin

inhibitor)

2 μg/kg/min. Adjust dose to maintain aPTT 1.5–3 times control (but <100 seconds)

Bivalirudin

†

(an analog of hirudin)

0.2 mg/kg/h. Adjust dose to maintain aPTT 1.5–2.5 times baseline.

Fondaparinux (a synthetic

pentasaccharide)

Not approved for HIT but may be useful as an alternative to heparin in patients with preexisting thrombocy-

topenia to avoid the development of HIT.

∗

Do not administer warfarin in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and deep venous thrombosis until platelet count is

>100,000 (potential risk for venous-limb gangrene). If anticoagulant therapy is necessary in a patient with a suspected history of heparin-

induced thrombocytopenia without complicating thrombosis, laboratory assessment for heparin-dependent antibodies (platelet activation

assay or antigen assay) may help determine risk of reexposure. If negative, short-term treatment with heparin along with careful monitoring

may be acceptable. Patients with a history of hepain-induced thrombocytopenia-associated thrombosis should be considered for alternative

anticoagulants.

†

FDA-approved for other indications (angioplasty).

Table 39–6. Management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

CHAPTER 39

830

once or twice daily (dosing depends on specific preparation)

and does not require laboratory monitoring using the aPTT.

These two factors make outpatient use of LMWH possible in

selected situations. LMWH preparations are excreted

renally, and the biologic half-life is prolonged in patients

with renal failure. The incidence of HIT appears to be less

with LMWH than with UFH. LMWH has been used in some

patients with HIT, but thrombocytopenia may persist.

Several LMWH preparations are now approved for use in

the United States: enoxaparin, dalteparin, and tinzaparin.

Selection of one preparation over another is difficult at pres-

ent because few studies comparing different preparations and

dosing regimens have been performed. Cost ultimately may

be as important as any other factor for choosing which

LMWH to use. The major advantage of LMWHs compared

with UFH relates to their convenience of administration, pre-

dictable anticoagulant response at a weight-adjusted fixed

dose, and lack of need for laboratory monitoring. Exceptions

include renal failure and obesity, in which cases monitoring

may be useful. In patients with creatinine clearances of less

than 30 mL/min, anti–factor Xa activity accumulates with

repeated dosing, although this varies among the different

LMWHs. Use of UFH may be preferable in these patients, but

when LMWH is needed, decreasing the dose and monitoring

anti–factor Xa activity should be performed to prevent over-

anticoagulation. Few studies have addressed dosing in very

obese patients. There does not appear to be an increased risk

of bleeding during therapeutic anticoagulation with LMWH

in obese patients, but most studies have included very few

markedly obese patients. Measuring anti–factor Xa activity 4

hours after subcutaneous administration may provide useful

information for dose reduction. Conversely, since obesity is

an independent risk factor for thromboembolism, weight-

based dosing or a 25% increase in fixed-dose LMWH may be

preferable for thromboprophylaxis in very obese patients. A

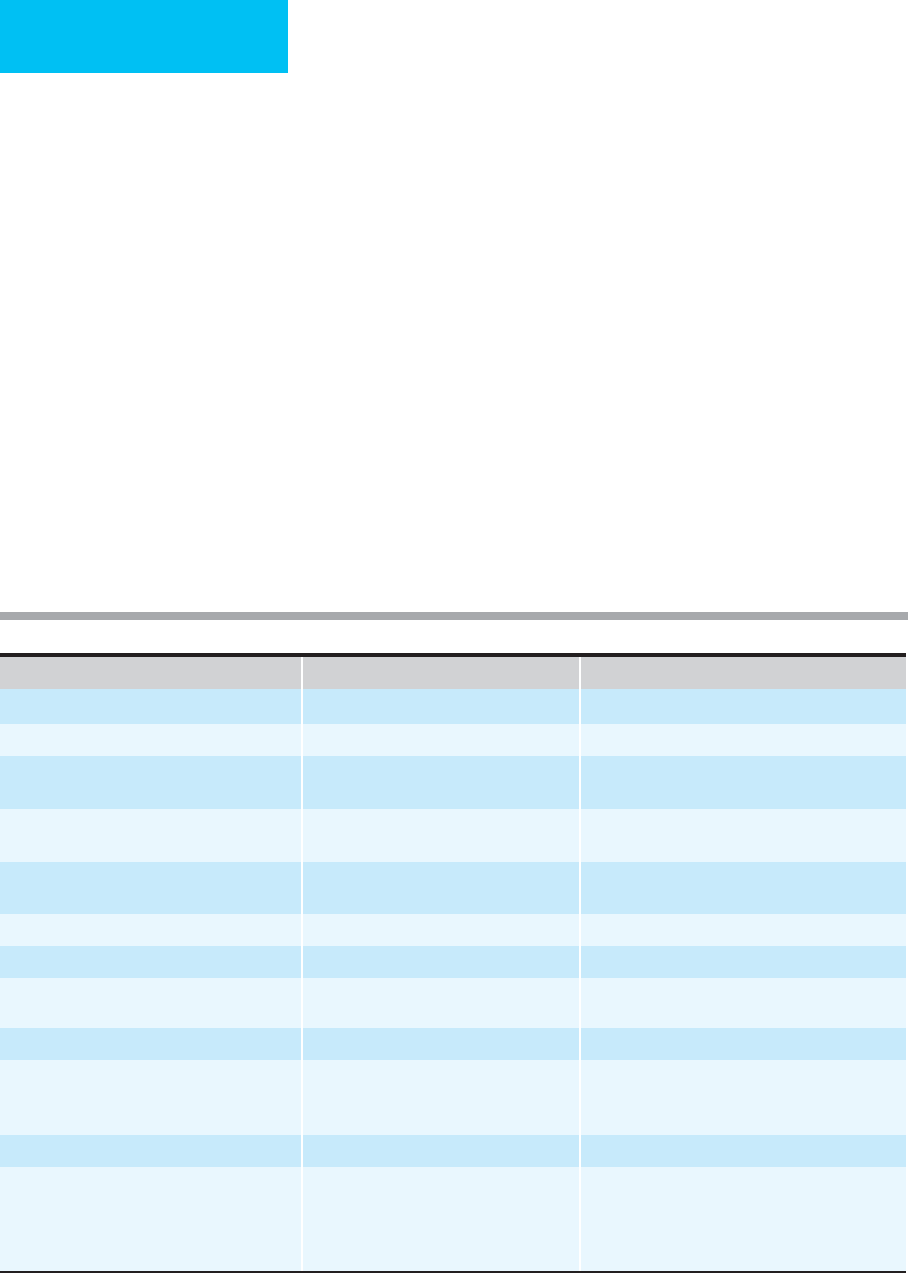

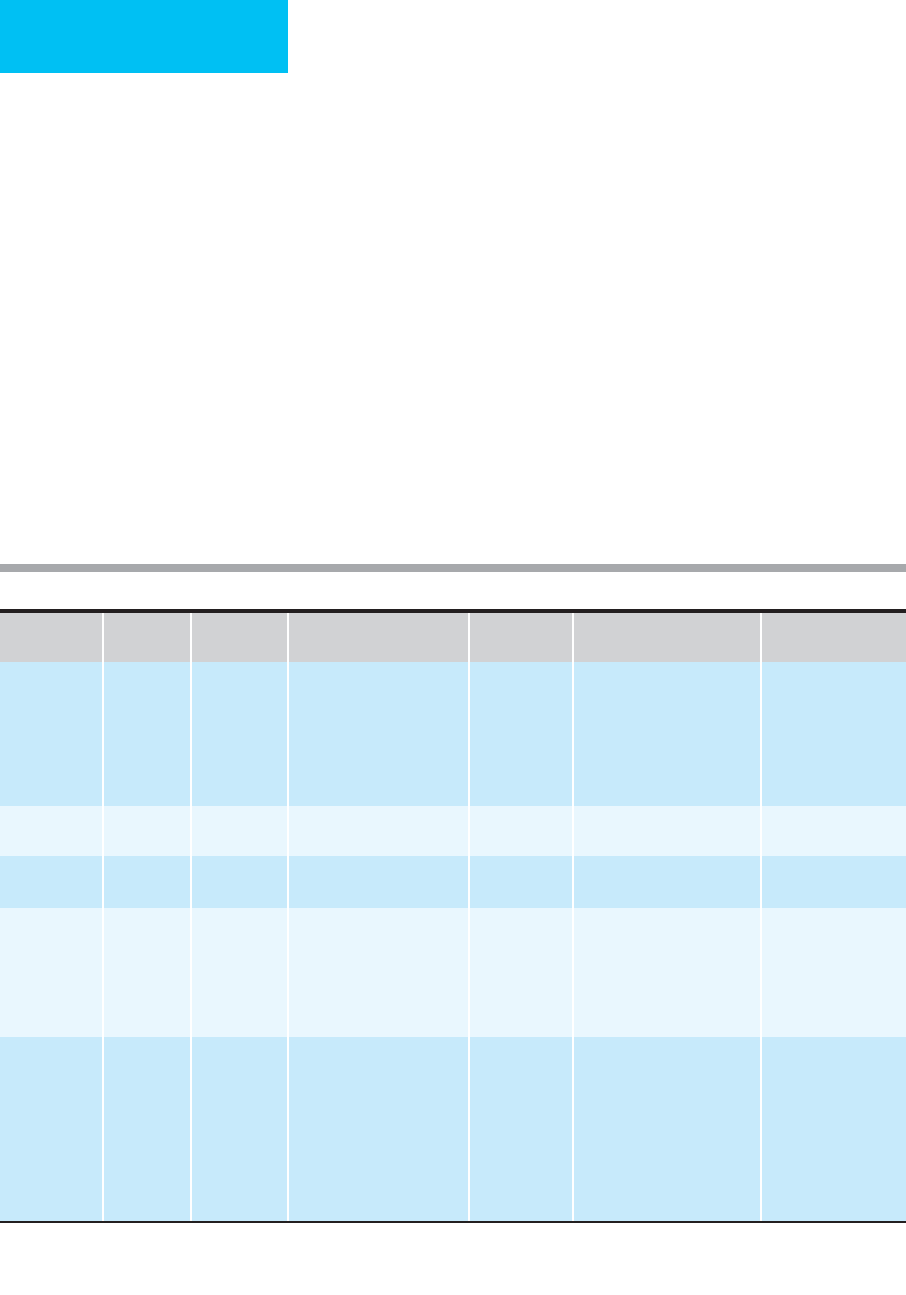

comparison of UFH and LMWH is presented in Table 39–7.

LMWH is effective for prevention of VTE in patients

undergoing major orthopedic procedures (eg, hip fracture or

replacement or knee replacement) or neurosurgery, after

major trauma (in patients eligible for anticoagulation), and

Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH)

Plasma half-life Dose-dependent; range 1–2.5 hours Increased; range 2–6 hours; prolonged in renal failure

Bioavailability Lower Better

Molecular weight: range

(Mean)

3000–30,000

(15,000)

100–10,000

(4500–5000)

Binding properties: proteins, cells (macrophages,

endothelium, osteoblasts)

High Low

Relative inactivation: Xa/IIa Lower Higher (five to six times compared with

unfractionated heparin)

aPTT Prolonged Not prolonged

Efficacy Equivalent Equivalent (most situations)

Major bleeding Approximately equivalent: 0–7% higher

(fatal, 0–2%), higher in acute stroke

Approximately equivalent: 0–3% (fatal, 0–0.8%),

higher in acute stroke

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia 2.5–6% Decreased

Osteoporosis 30%: decreased bone density;

15%: vertebral fractures

2–3%: vertebral fractures in pregnancy

Decreased

2.5%: vertebral fractures

Cost $15/d, full dose >$100/d, full dose

Reversibility with protamine sulfate (PS) Good: 1 mg PS/100 units UFH (bolus dose);

estimate for infusion based on total amount

in preceeding 2–3 hours.

Fair, not reliable: <8 hours since LMWH at 1 mg/100

anti-factor Xa units (1 mg enoxaparin = 100 units)

>8 hours: smaller dose.

Repeat with 50% of original dose if persistent

bleeding.

Table 39–7. Comparison of unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

831

in high-risk medical patients (see Table 39-4). LMWH is as

effective as UFH in the treatment of DVT and PE. It can be

administered to outpatients with acute DVT, but treatment

of PE may require hospitalization. LMWH is equivalent in

efficacy to warfarin for prevention of recurrent DVT follow-

ing acute DVT, with a lower incidence of minor bleeding, but

it is much more expensive. There also may be a higher rate of

rebound thromboembolism after discontinuation of the

drug than with warfarin.

The role of LMWH in coronary artery disease continues

to evolve as studies in various clinical syndromes are com-

pleted. LMWH is more effective than UFH in combination

with aspirin in the acute treatment of unstable angina and

non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. LMWH in

combination with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial

infarction has not been studied as extensively as UFH and

cannot be recommended until adequate studies demonstrate

efficacy and safety. LMWH may be used as an alternative to

UFH in patients undergoing PCI but is more difficult to

monitor and adjust than UFH. LMWH is not effective for

prevention of restenosis after coronary angioplasty and does

not reduce post-PCI ischemic events when administered fol-

lowing PCI. The use of LMWH is not recommended for

thromboprophylaxis in patients with prosthetic heart valves

but may be used as bridging therapy for these patients when

oral anticoagulation is temporarily interrupted.

Complications of therapy with LMWH are similar to

those seen with UFH heparin, with the exceptions of throm-

bocytopenia and osteoporosis, which occur less often with

LMWH. There may be less major bleeding in patients treated

for DVT with LMWH, but in most other situations the risk

is approximately equivalent to that seen with UFH. The use

of LMWH and heparinoids in the setting of spinal or

epidural anesthesia—or with spinal puncture—may cause

bleeding in the spinal column with subsequent prolonged or

permanent paralysis. If excessive bleeding does occur, labora-

tory assessment with a anti–factor Xa heparin assay can be

performed. The usual therapeutic range is between 0.5 and

1.0 unit/mL. When heparin anti–factor Xa is greater than

1.0 unit/mL, the aPTT also may be prolonged. Protamine

sulfate is much less effective for reversing the effect of

LMWH than UFH, but if serious bleeding occurs, protamine

sulfate, 1 mg per 100 anti–factor Xa units of LMWH (1 mg

of enoxaparin = 100 anti–factor Xa units), may be given, and

a smaller (50% of the original dose) dose may be given if

bleeding continues. Activated factor VII therapy recently has

been reported to reverse bleeding owing to LMWH, but has

not been adequately evaluated.

New Anticoagulants

Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

Lepirudin (a recombinant hirudin derivative), bivalirudin

(an analogue of hirudin), and argatroban are direct throm-

bin inhibitors that do not depend on antithrombin to exert

their anticoagulant effects. Unlike heparin, these agents bind

to free and clot-bound thrombin, do not bind to plasma pro-

teins, and are not neutralized by platelet factor 4. Hirudin

and argatroban are approved for use in HIT; bivalirudin is

approved for use as an alternative to heparin in patients

undergoing PCI (see Table 39–6). Studies of these agents in

other clinical settings have not shown clear advantages over

heparin, and there are no antidotes available to reverse the

anticoagulant effects of these drugs should bleeding occur.

Therefore, use of these agents has been restricted to the spe-

cific indications listed earlier. Lepirudin is cleared extensively

by the kidneys, requiring significant dose reduction and care-

ful monitoring in patients with renal impairment.

Bivalirudin has minor renal excretion and may be useful for

patients with impaired renal function as an alternative to lep-

irudin. Argatroban is a carboxylic acid derivative that inter-

feres with thrombin by binding to its active site. Several other

agents in this class are under investigation, some of them well

absorbed from the GI tract (eg, ximelagatran) with a pre-

dictable anticoagulant response, making laboratory moni-

toring unnecessary.

Indirect Thrombin Inhibitors

A. Pentasaccharide Analogues—These are synthetic ana-

logues of the pentasaccharide sequence responsible for bind-

ing heparin to antithrombin. They form a complex with

antithrombin that binds to and inhibits factor Xa; the pen-

tasaccharide is then released and can be reused. Fondaparinux

is the only agent in this class approved for use in the United

States for thromboprophylaxis following major orthopedic

surgery. It is administered subcutaneously once a day, is

excreted renally, and cannot be given to patients with creati-

nine clearances of less than 30 mL/min. Because it does not

bind to platelet factor 4, it should not cause thrombocytope-

nia. Fondaparinux is more effective than enoxaparin for pre-

vention of thromboembolism following major orthopedic

surgery. The rate of major bleeding may be higher than with

enoxaparin but appears to be similar if the first dose is given

6–8 hours after surgery. Fondaparinux is as effective as UFH or

LMWH in the initial treatment of VTE and is under investiga-

tion for patients with acute coronary syndromes. There is no

antidote for fondiparinux, but severe, uncontrolled bleeding is

potentially treatable with recombinant factor VIIa. However,

this extremely expensive agent is not available everywhere.

B. Heparinoids—Heparinoids are low-molecular-weight

glycosaminoglycuronans derived from porcine intestinal

mucosa. Danaparoid is available only outside the United

States for treatment of HIT and is a mixture of heparan sul-

fate, dermatan sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate. The small

heparan sulfate portion of this drug (4% of the total) has a

high affinity for antithrombin and is responsible for the major

anticoagulant effect of danaparoid. Dermatan sulfate also

mediates development of heparin cofactor II–thrombin com-

plexes and contributes to the anticoagulant effect. Danaparoid

has a higher ratio of anti–factor Xa activity compared with

CHAPTER 39

832

anti–factor IIa activity (20:1) than UFH (1:1) and LMWH

(2–4:1) and has fewer effects on platelet function than UFH.

It is similar to LMWH in its anticoagulant effects and has

minimal effect on coagulation parameters (ie, aPTT, PT, and

thrombin time), but it has certain structural differences (eg,

contains galactosamine, absent in LMWH) that distinguish it

from LMWH. A functional anti–factor Xa assay using dana-

paroid as the standard can be used to monitor the anticoag-

ulant effect of danaparoid when the agent is given for more

than 3 days. Danaparoid is as effective as lepirudin in the

treatment of HIT with less major bleeding. Danaparoid does

not cross the placenta, so it should be safe for treatment of

HIT during pregnancy.

Defibrinating Agents

Ancrod, an enzyme derived from the Malayan pit viper, is an

anticoagulant that cleaves fibrinogen and causes hypofib-

rinogenemia. Ancrod is licensed for use in Canada. Ancrod is

an effective anticoagulant that apparently causes minimal

excess bleeding. It is not associated with the development of

thrombocytopenia, is an excellent alternative anticoagulant

for patients with HIT, and has shown some promise in the

treatment of acute ischemic stroke. An initial dose of 1 unit/kg

is infused intravenously over 8–12 hours, followed by daily

maintenance doses adjusted for the level of fibrinogen

(see Table 39–7). Neutralizing antibodies develop with

long-term use, thus limiting its usefulness to situations in

which only short-term anticoagulation is required. An

antivenom is available to reverse its effect, and cryoprecipi-

tate also may be required for fibrinogen replacement if

excessive bleeding occurs.

Oral Anticoagulants

Warfarin

Warfarin (a 4-hydroxycoumarin compound) is the most

commonly used oral anticoagulant in North America.

Warfarin interferes with the metabolism of vitamin K,

inhibiting reduction of vitamin K to its active form, vitamin

KH

2

, in a two-step process in the liver. Vitamin KH

2

is essen-

tial for posttranslational modification (γ-carboxylation) of

the vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors and natural

anticoagulants (eg, factors II, VII, IX, and X and proteins C

and S). Decreased carboxylation of these important proteins

impairs their biologic function by impeding calcium-

binding capability and induces an anticoagulant effect.

Reduced protein C and S levels have the potential for causing

thrombosis, but in most situations, the anticoagulant effect

predominates.

Warfarin is absorbed rapidly from the GI tract, reaching

peak plasma levels in 90 minutes, circulates bound to plasma

proteins (97% albumin-bound), is metabolized in the liver,

and is excreted in urine and bile. The anticoagulant effect of

warfarin is not immediate. Until carboxylated coagulation

factors are adequately depleted, blood coagulation is normal.

The vitamin K–dependent proteins have plasma half-lives

ranging from 6 hours (factor VII) to 72 hours (prothrombin

and factor II). Proteins C and S have relatively short half-lives

(~8 hours). Because levels of factor VII, protein C, and pro-

tein S fall at about the same time—and 1–3 days before

depletion of the other coagulation factors—a relative hyper-

coagulable state may exist in the first 1–2 days after initiation

of warfarin. Although an observable anticoagulant effect

usually occurs after 2 days, the full antithromboic effect is

delayed for 4–5 days. The delayed effect may be of impor-

tance for patients with HIT and those with inherited or

acquired deficiency of protein C or protein S, who may be

particularly susceptible to warfarin-induced skin necrosis.

Whenever rapid anticoagulation is needed or in patients

with known thrombophilic states (eg, protein C or S defi-

ciency), heparin (UFH or LMWH) should be given for at

least 4 days at the start of warfarin therapy until the interna-

tional normalization ration (INR) is in the therapeutic

range. A loading dose of warfarin should not be given. The

initial dose should be between 5 and 10 mg for most patients

(lower for patients at high risk of bleeding or elderly

patients), with subsequent dosing based on results of the

INR. The average dose required to achieve a therapeutic level

by 4–5 days is 5 mg daily.

The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is assessed by in vitro

coagulation tests, the PT and aPTT. The therapeutic range

for warfarin depends on the indication for which it is used,

but at usual doses, the aPTT is normal or minimally pro-

longed, whereas the PT is maintained at 1.3 (low intensity) to

2.5 (high intensity) times control (PT ratio). Because of

marked interlaboratory variability in the sensitivity of the

thromboplastin reagents used in the PT assay, a standardized

approach has been adopted. This approach requires calibra-

tion of the thromboplastin to a reference preparation using

the international sensitivity index (ISI). Results then are

reported as the INR based on a formula comparing the PT

ratio obtained with the laboratory thromboplastin with that

with the reference thromboplastin. The therapeutic range of

warfarin for most indications ranges from an INR of 2–3

(low intensity) to an INR of 2.5–3.5 (high intensity). If the

thromboplastin reagent used by a clinical laboratory remains

constant, the PT and INR will be predictably related to each

other. Substitution of a reagent with either more or less sen-

sitivity, however, may dramatically alter the relationship of

the PT and INR. The INR is more reliable than the PT and is

the preferred method of reporting for warfarin monitoring.

It is important to fill the collection tube adequately when

measuring the INR because the concentration of the citrate

anticoagulant in the test sample affects the INR. Underfilling

the tube may lead to erroneously high INR results.

Although there is a direct dose-response relation, there is

marked variation in anticoagulant response to warfarin

among patients. There is also significant variability of antico-

agulant response during long-term therapy in individual

patients. This variability results from many factors, including

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

833

endogenous stores of vitamin K, changes in dietary intake or

recent therapeutic administration of vitamin K, genetically

determined differences in warfarin sensitivity, use of antibi-

otics (which may impair synthesis of vitamin K by intestinal

flora) or other drugs (which may increase or decrease war-

farin effect), the presence of liver disease, fat malabsorption

(including obstructive jaundice), hypermetabolic states,

pregnancy, poor patient compliance, and laboratory inaccu-

racy. In addition, elderly patients appear to be more sensitive

to warfarin, possibly owing to decreased clearance of war-

farin with age. Because of this marked variability, continued

monitoring is required, and most patients require dosage

adjustments periodically. Initial monitoring should be per-

formed daily until therapeutic and then two or three times

weekly until the INR is stable. When the PT or INR is stable,

monitoring every 4 weeks is usually adequate, although more

frequent monitoring may increase the amount of time the

PT or INR is in the therapeutic range (time in therapeutic

range [TTR]). Intensity of therapy and TTR are important

determinants of therapeutic efficacy of warfarin. More fre-

quent monitoring is advisable for elderly patients, those who

take multiple medications, or those who are at higher risk for

bleeding.

Although patients taking warfarin are commonly

instructed to limit their intake of vitamin K–rich vegetables,

it is preferable to suggest that the intake of these vegetables

remain relatively constant in the diet because the nutritional

benefits of these foods unrelated to vitamin K may be impor-

tant. Numerous drugs influence the anticoagulant effect of

warfarin through multiple mechanisms, and bleeding unre-

lated to the anticoagulant effect of warfarin may result from

effects on other hemostatic pathways (eg, aspirin and other

antiplatelet drugs and heparin), as well as effects on intestinal

mucosa (eg, aspirin). Before beginning warfarin therapy—or

before adding new medications when a patient is taking

warfarin—a review of potential interactions should be

undertaken (readily available in pharmaceutical handbooks

such as the Physicians’ Desk Reference or other drug com-

pendiums). The frequency of monitoring should be

increased in patients taking warfarin whenever new medica-

tions are started to allow proper dose adjustments.

The decision to use long-term oral anticoagulation is

based on an assessment of the risk to the patient of bleeding

compared with the potential benefits related to its anticoag-

ulant effect. Warfarin is effective for management of multiple

thromboembolic conditions and is used when long-term

anticoagulation is required. Candidates for long-term anti-

coagulation include those with artificial heart valves, chronic

atrial fibrillation, left ventricular mural thrombus, recurrent

cerebrovascular ischemia, and antiphospholipid antibody

syndrome.

The role of warfarin is well established and accepted in

the prevention and treatment of VTE. Long-term use is effec-

tive for prevention of recurrent VTE. Treatment for 3–6

months reduces the risk of recurrent VTE compared with

shorter durations of treatment. Patients with temporary or

reversible risk factors for VTE, such as surgery or trauma,

have a lower risk of recurrence and can be managed with

3 months of warfarin. For patients with idiopathic VTE,

extended treatment duration beyond 6 months reduces the

risk of recurrence but carries an increased risk of serious

bleeding, and when discontinued, the risk of recurrence

increases. Therefore, treatment duration for patients with

idiopathic VTE must take into consideration individual

patient characteristics and preferences. Two years of warfarin

therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent VTE

significantly (from 8.6–2.2%) in the subset of patients with

factor V Leiden or prothrombin 20210A mutation compared

with 6 months. Patients with antiphospholipid antibodies

have an increased risk of recurrent VTE and mortality (29%

and 15%, respectively) and should be considered for

extended duration of treatment with warfarin. Patients with

cancer have a higher risk of recurrent VTE and also should be

considered for longer term treatment with warfarin. Following

a second VTE, indefinite anticoagulation with warfarin

reduces the risk of recurrence compared with 6 months of

therapy from 20.7–2.6% but is associated with a threefold

increase in the risk of major bleeding. Careful patient

selection and monitoring are needed to balance the benefits

of longer-duration anticoagulation with its risks.

Warfarin is effective for prevention of systemic or cere-

bral emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation, artificial heart

valves, left ventricular mural thrombus, or very low left ven-

tricular ejection fractions. It is also effective for long-term

treatment of patients with peripheral arterial embolism and

may prevent thrombosis of peripheral arterial bypass grafts

in high-risk patients. Antiplatelet agents are preferred over

warfarin for the prevention of acute myocardial infarction in

patients with peripheral arterial disease; for prevention of

stroke, recurrent infarction, or death in patients with acute

myocardial infarction; and for prevention of myocardial

infarction in men at high risk, but cardiac mortality is

reduced in the highest-risk patients by combining low-

intensity warfarin with aspirin. This combination carries a

risk of cerebral hemorrhage if blood pressure is not moni-

tored and controlled. Warfarin is not better than aspirin for

prevention of recurrent stroke, even in patients taking

aspirin at the time of the stroke, but is still recommended by

some neurologists for patients with recent noncardiac

embolic strokes or TIAs. Low-dose warfarin (0.5–1 mg/day)

is often used to prevent thrombosis of vascular access

catheters in cancer patients and to prevent thrombosis asso-

ciated with thalidomide therapy, but efficacy has not been

established for these situations.

The target INR for most indications is 2–3. A higher INR

(2.5–3.5) is recommended for patients with certain pros-

thetic heart valves (eg, tilting-disk and bileaflet mitral valves

and caged-ball or disk valves). Higher-intensity warfarin

may be considered for patients with recurrent VTE occur-

ring on therapeutic doses of warfarin or thrombosis associ-

ated with antiphospholipid antibodies (although this

remains controversial). Lower-intensity warfarin treatment

CHAPTER 39

834

(INR 1.5) is recommended when it is combined with aspirin

for prevention of fatal coronary events in patients at very

high risk.

Bleeding is the most common complication of warfarin

and is related to the intensity of the anticoagulation (espe-

cially in patients over 75 years of age), concomitant use of

aspirin, coexisting hemostatic defects (including renal fail-

ure), age over 75 years, history of GI bleeding, cancer, pres-

ence of anemia, and history of stroke or atrial fibrillation. If

GI bleeding or hematuria occurs when the INR is less than

3.0, an underlying GI or renal lesion should be suspected,

although spontaneous bleeding may occur when the INR is

in the high-intensity range or above. Prolonged use (lifelong)

also may increase the cumulative risk of bleeding. Patients

who consume excess alcohol or those who suffer from fre-

quent falls have a much higher risk of serious bleeding. There

are rare patients who have been identified to have mutations

in factor IX that cause an unusual susceptibility to bleeding

without prolongation of the INR.

Overdosage of warfarin (accidental or intentional) may

lead to serious bleeding. Management of hemorrhage associ-

ated with warfarin is similar to that encountered with

heparin in terms of using clinical criteria to determine the

urgency of the situation. Mild excess prolongation of the INR

(<5.0) without hemorrhage should be managed expectantly

by withholding warfarin until the INR returns to the desired

range and then resuming at a lower dose. Serious bleeding

may require immediate reversal with fresh-frozen plasma

(2–3 units) to provide functional vitamin K–dependent fac-

tors. Because vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin that is stored

in the liver, reversal of warfarin effects with vitamin K may

result in resistance to subsequent warfarin therapy. Low-dose

oral vitamin K

1

(phytonadione, 1–2.5 mg) will lower the INR

to less than 5 in patients with INR values between 5 and 9,

and 5 mg will correct INR values of greater than 9 in the

majority of patients within 24 hours without inducing war-

farin resistance. Intravenous vitamin K

1

should be reserved

for patients with an urgent need to reverse anticoagulation—

particularly patients with life-threatening hemorrhage not

controlled by fresh frozen plasma who will not require sub-

sequent warfarin therapy.

Patients receiving chronic warfarin therapy undergoing

invasive procedures likely to cause bleeding may require

interruption of warfarin. Depending on the patient’s risk for

perioperative thromboembolism, coverage with UFH or

LMWH may be necessary until the patient resumes warfarin.

Dental procedures may not require interruption of warfarin;

local hemostasis can be achieved with the use of topical

agents, such as tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid

mouthwashes. Tables 39–8 and 39–9 summarize guidelines

proposed by the American College of Chest Physicians for

warfarin therapy (ie, dose, monitoring, adjustment, and peri-

operative management). Included in Table 39-9 are sug-

gested strategies for reversal of warfarin when time does not

permit withholding warfarin for several days (eg, for urgent

or emergent surgery).

Warfarin skin necrosis is a rare but serious complication

of warfarin, usually occurring 2–7 days after initiation of

warfarin therapy. Extensive thrombosis of venules and cap-

illaries of subcutaneous fat, particularly in the lower extrem-

ities, buttocks, or breast, appears to be most common in

patients who have an inherited or acquired deficiency of

Initial dose: 5 mg/d (lower in patients who are elderly, on multiple medications, malnourished, or have liver disease).

Check INR daily until therapeutic, then two or three times per week until stable, then every 4 weeks.

INR Intervention

Subtherapeutic Increase dose. Continue frequent monitoring until therapeutic.

Therapeutic (range based on underlying condition

requiring anticoagulation)

Continue current dose.

Between therapeutic range and 5 Omit dose. Resume at a lower dose when INR is therapeutic.

5.0–9.0, no bleeding Omit 1 or 2 doses. Resume at a lower dose when INR is therapeutic

OR give vitamin K

1

, 1–2.5 mg orally. Resume warfarin at reduced dose

when therapeutic.

>9.0, no bleeding Hold warfarin, give vitamin K

1

, 3–5 mg orally. Resume warfarin at

reduced dose when therapeutic.

>20.0

or

serious bleeding Hold warfarin. Give vitamin K

1

, 10 mg by slow intravenous infusion.

Supplement with fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concen-

trate if needed.

Table 39–8. Administration and monitoring of warfarin.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

835

protein C or protein S. Patients who are known to be defi-

cient in protein C or protein S should receive warfarin only

with simultaneous administration of heparin for at least

5 days to allow for depletion of all the vitamin K–dependent

coagulation proteins to prevent skin necrosis.

Warfarin is teratogenic, resulting in a fetal embryopathy

associated with multiple anomalies when is administered

during the first trimester of pregnancy (estimated incidence

7–28%). Warfarin crosses the placenta and may result in fetal

bleeding. Because of these negative fetal effects, warfarin is

contraindicated between weeks 6 and 12 of pregnancy, and

because it may cause fetal bleeding, it should be avoided near

term. Women of reproductive age who are taking warfarin

should be advised of the teratogenic effects of the drug, and

if pregnancy is contemplated, UFH or LMWH should be

substituted prior to pregnancy (except for women with

mechanical heart valves; see “Antithrombotic Therapy in

Pregnancy”). Warfarin does not cause anticoagulation in

infants who are breastfed by mothers taking warfarin.

Other infrequent side effects of warfarin include alopecia,

GI discomfort, rash, and liver dysfunction. In patients with

underlying arterial vascular disease, warfarin therapy has

been associated rarely with the development of atheroem-

bolic complications, including ischemic toes, livedo reticularis,

gangrene, abdominal pain, and renal and other visceral

infarctions owing to cholesterol emboli. Early reports sug-

gested that chronic warfarin therapy may increase the risk of

bone fractures and osteoporosis, but a meta-analysis of avail-

able studies failed to show a definite association.

Anisindione

Patients who cannot tolerate warfarin may be treated with

anisindione, an oral anticoagulant that is structurally unre-

lated to warfarin but works by a similar mechanism, namely,

inhibition of γ-carboxylation of the vitamin K–dependent

coagulation factors. The drug is well absorbed from the GI

tract, is highly protein-bound, and is metabolized to inactive

metabolites that are excreted in the urine. These metabolites

may cause a red-orange discoloration of the urine. The anti-

coagulant response of anisindione occurs within 20–72

hours, and it is cleared slowly from circulation with a half-life

of 3–5 days. Like warfarin, its anticoagulant effect can be

reversed by vitamin K and fresh-frozen plasma. Anisindione

crosses the placenta and causes fetal malformations and fetal

bleeding, so it should be avoided during pregnancy.

Anisindione is FDA approved for use in myocardial

infarction and venous thrombosis, but there is a lack of good

Low risk for thromboembolism (VTE >3 months ago or atrial

fibrillation without stroke risk factors)

Stop warfarin 4 days before surgery. Give heparin (UFH or LMWH) briefly at prophylactic

doses and resume warfarin simultaneously in the postoperative period.

Intermediate risk for thromboembolism Stop warfarin 4 days before surgery. Use low-dose UFH or prophylactic dose of LMWH

starting 2 days before surgery. After surgery, resume warfarin and continue heparin

until INR therapeutic.

High risk for thromboembolism (VTE <3 months ago; multiple

VTE; mechanical mitral valve; ball-and-cage prosthetic heart

valve)

Stop warfarin 4 days before surgery. Start full-dose intravenous or subcutaneous

heparin or LMWH when INR falls (usually about 2 days before surgery). Stop heparin before

surgery (5 hours for intravenous or 12 hours for subcutaneous UFH or LMWH). Resume

warfarin and continue heparin postoperatively until INR therapeutic.

Low risk of bleeding Continue warfarin at lowered dose (INR 1.3–1.5) for 4–5 days before surgery.

Resume full dose postoperatively. Use prophylactic dose of heparin until INR

therapeutic.

Dental procedures with low risk of bleeding Continue warfarin at usual dose and INR.

Dental procedures with higher risk of bleeding Continue warfarin at usual dose and INR. Use tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid

mouthwash to control bleeding.

Urgent/emergent surgery (1–8 hours) Vitamin K 10 mg IV over 30 minutes and fresh frozen plasma (2–4 units depending

on INR < or >2.5).

Urgent/emergent surgery (8–12 hours) Vitamin K 10 mg IV over 30 minutes and fresh frozen plasma (2 units if INR >2).

Urgent/emergent surgery (12–24 hours) Vitamin K 10 mg IV or SC; UFH if high risk for thromboembolism until 6 hours before

surgery.

Urgent/emergent surgery (24+ hours) Vitamin K 10 mg SC if INR >2; UFH if high risk for thromboembolism until 6 hours

before surgery.

VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Table 39–9. Management of warfarin during invasive procedures.

CHAPTER 39

836

clinical studies to support its use as a substitute for warfarin

except for patients who are truly intolerant of warfarin. In

those patients, a loading dose of 300 mg on day one, 200 mg

on day two, and 100 mg on day three is followed by daily

maintenance of 50–250 mg, adjusted according to the INR.

Anisindione may cause myelosuppression, dermatitis, jaun-

dice, and renal insufficiency, which have limited its use.

Thrombolytic Therapy

Thrombolytic (fibrinolytic) agents differ from other

antithrombotic agents in that they actually dissolve estab-

lished clots rather than interfering with initiation and prop-

agation of thrombosis. The mechanism of action of these

agents is complex and involves many components of the nat-

urally occurring fibrinolytic system. Activation of plasmino-

gen to plasmin (the major fibrinolytic enzyme) is enhanced

by these drugs, accompanied by increased consumption of its

inhibitor (α

2

-antiplasmin). The net effect is an increase in

free plasmin, which results in degradation of fibrin and other

coagulation factors.

All the available agents cause varying degrees of systemic

activation of the fibrinolytic mechanism and therefore induce

generalized fibrinolysis and fibrinogenolysis and some degree

of platelet dysfunction owing to proteolysis of key membrane

receptors by plasmin, although some are more specific for

plasmin bound to clot (fibrin-specific). These drugs work best

when given soon after onset of symptoms (eg, within 3–4

hours in acute arterial thrombosis, 48 hours for pulmonary

thromboembolism, and 7 days for DVT), before thrombi are

highly cross linked and more resistant to thrombolysis.

Five thrombolytic agents are approved for use in the

United States. Selected features of these agents are outlined in

Table 39–10. Thrombolytic therapy may be used in the treat-

ment of acute arterial thrombosis, including myocardial

infarction and peripheral arterial occlusion, and in the treat-

ment of severe VTE (eg, massive pulmonary thromboem-

bolism with hemodynamic compromise, massive DVT, or

phlegmasia cerulea dolens). Thrombolysis can improve neu-

rologic function in patients with acute nonhemorrhagic stroke

if patients at high risk for bleeding are excluded and if

Drug

t

1⁄2

(min)

Fibrin-

Specific

Indications

(FDA-Approved)

Neutralizing

Antibodies

∗

Typical Dose

†

Estimated Cost

Alteplase 5 Yes

(2+)

Myocardial infarction, acute

cardiovascular accident, pul-

monary thromboembolism

No Myocardial infarction: 100 mg

infusion over 90 minutes to

3 hours; cerebrovascular

accident: 0.9 mg/kg (maxi-

mum 90 mg) infused over

60 minutes with 10% of total

dose given as an initial bolus

$2200

Tenecteplase 18–20 Yes

(3+)

Myocardial infarction. No Single bolus, 30–50 mg

depending on weight in kg

$2200

Reteplase 13–16 Yes

(1+)

Myocardial infarction No Two bolus injections, 10 units

each given 30 minutes apart

$2200

Streptokinase 20 No Myocardial infarction (intra-

venous or intracoronary),

deep vein thrombosis, pul-

monary thromboembolism,

catheter thrombosis, periph-

eral arterial occlusion

Yes 1.5 million units infused over

30–60 minutes intravenously

OR

20,000 units by intracoronary

bolus followed by 2000 to 4000

units/min for 30 to 90 minutes

$300

Urokinase 20 No Myocardial infarction (intra-

coronary), pulmonary

thromboembolism, catheter

thrombosis

No 6000 units/min infused intra-

coronary for up to 2 hours

OR

4400 units/kg infused over

10 minutes followed by 4400

units/kg/hr for 12 hours

OR

5000 units for catheter

thrombosis

$4000–$6000 (myocar-

dial infarction, pul-

monary embolus) $60

(catheter thrombosis)

∗

Presence of neutralizing antibodies precludes repeat use within 6–24 months, possibly longer, because of allergic reactions and decreased

effectiveness of the agent.

†

Doses may vary depending upon clinical situation.

Table 39–10. Comparison of selected fibrinolytic agents.