Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

837

administered within 3 hours of onset of symptoms.

Thrombolytic agents are also used to reestablish patency of

clotted indwelling venous catheters and vascular grafts.

Indications, timing of administration, use of adjunctive

antithrombotic agents, and choice of specific agent for throm-

bolytic therapy are evolving. Thrombolysis reduces mortality

from acute myocardial infarction by about 20–50%. In

patients not undergoing percutaneous transthoracic coronary

angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction, alteplase may be

more effective than streptokinase. Bolus fibrinolytic agents,

reteplase and tenecteplase, are potentially advantageous

because they can be given quickly and could be available in the

prehospital setting. Reteplase appears to be equivalent in safety

and efficacy to alteplase, whereas tenecteplase has a somewhat

lower rate of major bleeding. Any available fibrinolytic agent

may be used with acute myocardial infarction. Although the

newer agents are much more expensive than streptokinase, the

contribution of drug costs to the overall cost of care—particu-

larly for acute myocardial infarction—has not been shown to

be significant. When cost-effective analyses have been done,

streptokinase appears to be marginally more cost-effective than

the other agents but should not be given to patients previously

treated with streptokinase owing to its antigenicity. Urokinase

is used primarily for dissolution of catheter thromboses.

The principal goal of fibrinolytic therapy is to reestablish

patency of an occluded blood vessel (or indwelling catheter).

Fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction results in

angiographically confirmed patency about 50% of the time.

Additional antithrombotic therapy may be required to

improve reperfusion. The role of heparin combined with fib-

rinolytics for patients with acute myocardial infarction is

controversial, and the combination appears to be associated

with a high rate of major bleeding. Ongoing studies are

required to define the optimal use of heparin (UFH or

LMWH) or other anticoagulants such as the hirudin deriva-

tives and heparinoids in combination with fibrinolytic ther-

apy. Antiplatelet agents have been shown to be very

important as an adjunct to fibrinolytic therapy. Platelets play

a key role in the development of coronary thrombosis.

Aspirin and platelet GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors potentiate fibri-

nolysis and improve coronary artery patency rates, although

bleeding complications also may be increased when streptok-

inase is combined with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Large trials

recently completed will provide additional information

about the safety and efficacy of various combinations of

antiplatelet agents and fibrinolytics in the treatment of acute

myocardial infarction. In addition, the combination of

reduced-dose fibrinolytic therapy with invasive coronary

interventions (eg, angioplasty) may improve outcomes.

Further study in this area is needed to define optimal dosing

to enhance coronary artery patency while maintaining an

acceptable rate of hemorrhage.

Alteplase is approved for use in acute nonhemorrhagic

stroke and is effective when administered intravenously

within 3 hours of the onset of symptoms. The risk of intra-

cerebral hemorrhage is 3%, but because it can lead to improved

neurologic function, this may be an acceptable risk. Only an

estimated 2% of all stroke patients are able to receive

alteplase within the 3-hour time frame, limiting its potential

impact on outcomes from stroke. Streptokinase increases

early mortality and intracerebral hemorrhage when used in

the treatment of acute stroke and is not recommended.

Recently, MRI to locate arterial occlusions, followed by

superselective intraarterial thrombolysis, has been suggested

as a potentially beneficial approach for patients with acute

stroke who are more than 3 hours from the onset of symp-

toms. This approach has an even higher risk of hemorrhage

(10% overall), but in centers equipped with a stroke unit and

all necessary personnel and technologic support quickly

available, it may prove to increase the number of patients

who could benefit from thrombolysis for acute stroke.

Fibrinolytic therapy is of limited value in the treatment of

massive PE. Hemodynamic instability and radiographic

changes improve more rapidly than with anticoagulation

only, but there does not appear to be any significant

improvement in overall outcome compared with anticoagu-

lation alone. Fibrinolytic therapy of PE should be considered

for patients with hemodynamic instability, severe gas-

exchange abnormalities, or significant impairment in right

ventricular function. Echocardiography to assess right ven-

tricular function plays a key role in determining the potential

benefit of fibrinolytic therapy or other means of reducing

clot burden (eg, thromboembolectomy). Fibrinolytic therapy

for DVT has not improved outcome over anticoagulation in

most patients, with the possible exception of patients with

severe venous occlusion and threatened gangrene of the

limb. Despite a high rate of clot lysis, there is no good evi-

dence that thrombolytic therapy reduces the rate of post-

phlebitic syndrome following DVT. Furthermore,

hemorrhagic complications are much higher than with stan-

dard anticoagulation in the treatment of VTE.

Fibrinolytic therapy is effective in the treatment of acute

arterial thrombus in medium and large peripheral arteries. A

fibrinolytic agent administered through a catheter proximal

to the clot dissolves it completely about 75% of the time.

Catheter-directed intraarterial administration appears to be

superior to intravenous administration. Thrombolysis

should be considered prior to revascularization surgery as

long as the affected limb is still salvageable. Surgery can be

avoided in 35% of these patients, and overall mortality

appears to be somewhat better than with immediate surgery.

Urokinase, 5000 units, may be instilled into an occluded

venous catheter without excessive pressure, which could dis-

lodge the clot or rupture the catheter. Because venous

catheters may be occluded by substances other than clots (eg,

drug precipitate), urokinase is not always effective.

The most common complication of thrombolytic therapy

is hemorrhage (3–40%). Hemorrhagic complications can be

minimized if patients are selected properly and monitored

carefully. The use of other antithrombotic agents—particularly

heparin—increases the risk of bleeding. Contraindications to

thrombolytic therapy include major ischemic changes or

CHAPTER 39

838

signs of intracranial hypertension on CT scan, seizure at the

onset of a stroke, previous stroke or serious head injury

within the preceding 3 months, active or recent visceral

bleeding, aortic dissection, major surgery, trauma, arterial or

lumbar puncture in the preceeding 2 weeks, severe uncon-

trolled hypertension (>180/110 mm Hg), significant throm-

bocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/μL), signs of

pericarditis, pregnancy, recent retinal laser surgery, cardio-

genic shock (except when owing to massive PE), and the use

of heparin with a prolonged aPTT or oral anticoagulants

resulting in an INR greater than 1.5. Thrombolytic therapy

results in decreased plasma fibrinogen concentration and

increased fibrin degradation products, but these tests are not

predictive of efficacy or clinical bleeding. The bleeding time,

if prolonged, may correlate with minor bleeding but is not

usually monitored.

The thrombin time is the best laboratory test for moni-

toring the status of the fibrinolytic system. When the throm-

bin time is prolonged more than five to seven times normal,

the incidence of bleeding complications increases signifi-

cantly. Intracerebral hemorrhage is more common in patients

who are elderly or underweight, who have prior neurologic

disease, or who are receiving antithrombotic drugs. Women

appear to have a higher risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. If

major bleeding occurs with thrombolytic therapy, the drug

should be stopped immediately. Hypofibrinogenemia can

be reversed with cryoprecipitate, and aminocaproic acid

can be given to inhibit plasmin activity. If the patient is

receiving heparin, protamine sulfate can be used to reverse

its effect.

Other potential adverse reactions to certain thrombolytic

agents (eg, streptokinase and anistreplase) include allergic

reactions and the development of neutralizing antibodies

that preclude repeated usage for 6–24 months and perhaps

longer. Cholesterol emboli rarely may complicate throm-

bolytic therapy, resulting in the “purple toe syndrome” and

multiorgan failure. Arrhythmias may accompany reperfusion

of an ischemic myocardium.

Antithrombotic Therapy in Pregnancy

Pregnancy and the postpartum period pose special chal-

lenges in the management of thromboembolic disorders. In

addition to the apparent increased risk of venous thrombo-

embolic events, certain pregnancy complications (eg, fetal

loss, preeclampsia, abruption, fetal growth retardation, and

intrauterine death) are associated with maternal throm-

bophilias (eg, antiphospholipid antibodies, factor V Leiden,

prothrombin gene mutation, antithrombin deficiency, and

hyperhomocysteinemia). In addition, women who are taking

warfarin for preexisting conditions (eg, venous thromboem-

bolism or mechanical heart valves) require continued

antithrombotic therapy during this higher-risk period.

Warfarin is contraindicated between 6 and 12 weeks of preg-

nancy because of its teratogenicity and because it may

increase the risk of fetal bleeding. UFH does not cross the

placenta and appears to be safe and effective during preg-

nancy. LMWH and danaparoid have a lower risk of osteo-

porosis and thrombocytopenia than UFH. Dosing may be

adjusted for increasing weight, or anti–factor Xa levels

(drawn 4 hours after morning dose) can be monitored (tar-

get range 0.5–1.2 units/mL). Because these agents do not

cross the placenta, fetal bleeding is not a complication; how-

ever, there have been recent reports of congenital anomalies

with some of the LMWH preparations (eg, enoxaparin and

tinzaparin), and there has been insufficient clinical experi-

ence with danaparoid during pregnancy to determine its ter-

atogenicity. Maternal bleeding occurs with the same

frequency as in other situations requiring anticoagulation

(major bleeding, about 2%). Bleeding can complicate deliv-

ery. The aPTT may not adequately reflect the anticoagula-

tion effect of UFH because of increased factor VIII and

fibrinogen that occurs during pregnancy. When possible,

UFH or LMWH should be discontinued 24 hours before

labor (eg, when electively induced). UFH and LMWH are

not secreted in breast milk, and warfarin does not appear to

cause an anticoagulant effect in babies who are breastfed by

mothers taking warfarin. Guidelines for the management of

antithrombotic agents during pregnancy are outlined in

Table 39-11.

The use of heparin (UFH and LMWH) during pregnancy

appears to be effective for prophylaxis and treatment of VTE.

In women with mechanical heart valves, heparin is not be as

effective as warfarin for prevention of thromboembolic com-

plications, particularly if the aPTT is only moderately ele-

vated. Choices for anticoagulation in these women include

using warfarin (target INR 3.0), except for weeks 6–12 and

near delivery, when UFH can be substituted, to prevent fetal

embryopathy or bleeding, or to use UFH throughout preg-

nancy. If UFH is used, it is imperative that high doses be used

and that the aPTT (6 hours after subcutaneous injection) is

monitored closely. The addition of low-dose aspirin (81–162

mg/day) may reduce the risk of thrombosis but also increases

the risk of bleeding. Maternal and fetal deaths from throm-

botic complications have been reported when enoxaparin

was used for thromboprophylaxis in pregnant women with

prosthetic heart valves; however, the incidence of this com-

plication is not known. The optimal approach for manage-

ment of anticoagulation for women with mechanical valves

during pregnancy is not clear owing to a lack of sufficient

clinical trials.

Low-dose aspirin appears to be safe when administered in

the second and third trimesters to modestly reduce the risk

of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation in high-

risk women and appears to be safe for both mother and fetus.

Additional studies are required to determine the optimal

selection of patients, timing, and dose of aspirin therapy.

Low-dose aspirin combined with heparin reduces the risk of

miscarriage in women with the antiphospholipid antibody

syndrome and recurrent miscarriage, but it is uncertain

whether this strategy is effective in women with other throm-

bophilic conditions.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

839

Women at high risk for thromboses during pregnancy,

such as those with prior VTE, inherited thrombophilic disor-

ders, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (without

prior thrombosis or miscarriage), should be considered for

prophylactic anticoagulation with UFH or LMWH during

pregnancy and the postpartum period. Determining the

optimal management strategy for these patients is difficult

because there are inadequate data available to support spe-

cific recommendations. A discussion of the potential risks

and benefits, known and uncertain, with each patient must

be undertaken at the onset of pregnancy.

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

Significant thrombotic events in the presence of the

antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLA) pose special

therapeutic challenges. Acute management with heparin may

be complicated by baseline elevation in the aPTT. If baseline

aPTT is prolonged, monitoring should be performed using a

specific heparin assay that depends on factor Xa inhibition

(therapeutic range 0.3–0.7). LMWH can be used without the

need for laboratory monitoring. The optimal intensity and

duration of warfarin therapy (following initial therapy with

UFH or LMWH) for these patients is unclear, but higher-

intensity warfarin (INR at least 3) is probably superior to

lower-intensity warfarin, and longer-duration therapy (2–4

years) offers a lower rate of recurrence than 6 months of

anticoagulation. Low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) should be

added to oral anticoagulation for arterial thrombosis or for

recurrent VTE despite adequate oral anticoagulation.

Heparin therapy (UFH or LMWH) has been advocated by

some for patients with APLA syndrome, but there is no direct

evidence that it is superior if INR is monitored and adjusted

carefully. Some patients also have hypoprothrombinemia,

with baseline prolongation of the PT, which makes monitor-

ing with INR unreliable. Coagulation tests that are insensi-

tive to the lupus anticoagulant may be required in these

patients (eg, prothrombin-proconvertin test or chromogenic

factor X level). Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive

agents may improve coagulation abnormalities, but the ben-

efits are usually short-lived. If patients have multisystem

involvement, corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, and

plasmapheresis may be beneficial; however, ongoing treat-

ment of the thrombotic diathesis with anticoagulation is

advisable. Management of APLA syndrome during preg-

nancy was discussed earlier.

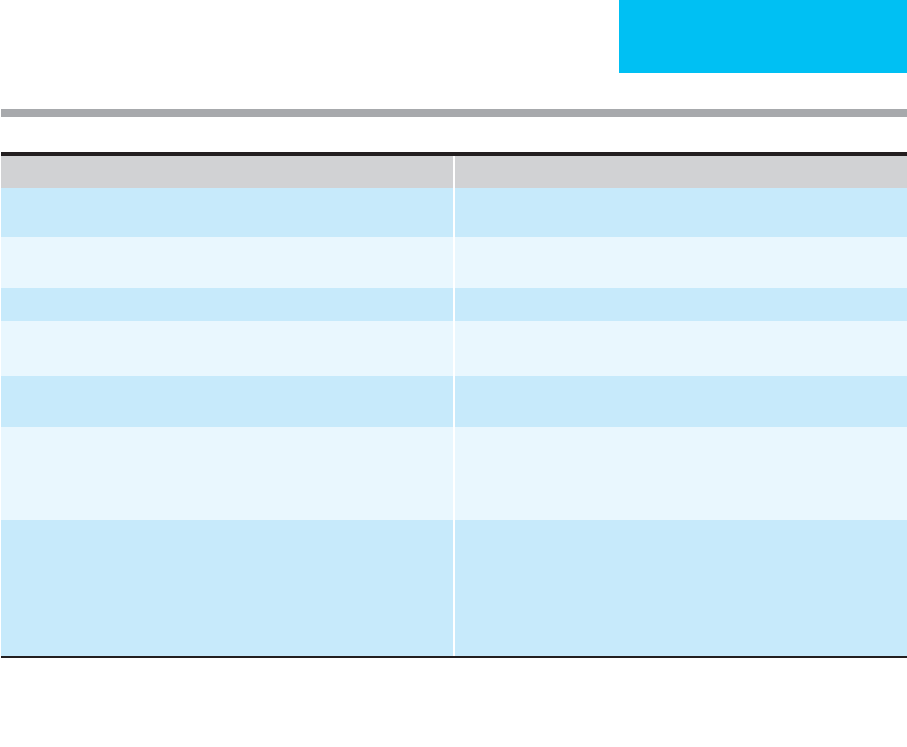

Table 39–11. Antithrombotic therapy during pregnancy.

Clinical Situation Recommendation

Women on long-term anticoagulation who wish to become pregnant Frequent pregnancy tests; convert to LMWH or adjusted-dose UFH once

pregnant

VTE during pregnancy LMWH or adjusted-dose UFH throughout pregnancy and for at least

6 weeks postpartum

Prior VTE with transient risk factors

∗

Close surveillance during pregnancy; postpartum anticoagulation

†

Prior VTE with thrombophilia or family history

∗

Low- to moderate-dose UFH or LMWH throughout pregnancy; postpartum

anticoagulation

Multiple prior VTE

∗

LMWH or adjusted-dose UFH throughout pregnancy; resume long-term

anticoagulation postpartum

Thrombophilia without history of VTE No clinical data to support specific recommendation; consider prophylaxis

for patients with AT deficiency, factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A

heterozygotes, homozygous factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A

mutation

Mechanical heart valve Options:

1. LMWH, monitor anti-Xa activity

2. Adjusted-dose UFH

3. LMWH or adjusted-dose UFH until week 13; warfarin until mid-third

trimester, resume LMWH or UFH until term

4. Consider adding aspirin, 75–162 mg/day for high-risk women

∗

Recommendations should be individualized; very low recurrence of VTE in small study of these patients.

†

All pregnant women with history of VTE should consider use of graduated compression stockings throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

CHAPTER 39

840

Immunologically mediated thrombocytopenia is com-

mon in APLA syndrome but generally is mild and does not

require treatment. When severe thrombocytopenia

(<20,000/μL) is present, increased bleeding during anticoag-

ulation may occur. Treatment as for other immune thrombo-

cytopenias should be given to achieve a reasonable platelet

count (ie, >50,000/μL) to decrease the risk of serious hemor-

rhage with concomitant anticoagulation. Catastrophic APLA

syndrome (eg, multiorgan and bowel thrombosis, gangrene,

livedo reticularis, and stroke) requires aggressive therapy

with anticoagulation, plasmapheresis, and immunosuppres-

sive agents but is associated with a high rate of mortality

despite these measures.

Thrombosis in Cancer Patients

The risk of thrombosis in patients with cancer is significant

and is due to several factors, many of which may be present

simultaneously: activation of coagulation by tumors, throm-

bocytosis, tumor angiogenesis, trapping of cancer cells in the

microcirculation of organs, treatment (ie, chemotherapy and

hormonal therapy), indwelling vascular catheters, obstruc-

tion of venous and lymphatic channels, surgical procedures,

and limited mobility. Postoperative VTE is much higher in

patients undergoing cancer surgery, and recurrence of VTE

after completion of anticoagulation is more common in

patients with cancer. Patients undergoing major cancer sur-

gery, especially when associated with prolonged immobility,

should be considered for thromboprophylaxis with LMWH

postoperatively. Extending the duration of prophylaxis from

8–10 days to 4 weeks reduces the risk of VTE from 12–4.8%.

LMWH may be superior to warfarin for the treatment of

established VTE in cancer patients, reducing the rate of treat-

ment failure and improving survival. Studies have shown

conflicting results with LMWH therapy for patients with

advanced malignancy without established VTE. There may

be a small survival advantage for selected patients with bet-

ter initial prognosis, but the risks of bleeding, cost, and

inconvenience to the patient must be considered before initi-

ating therapy. Prevention of catheter-associated thrombosis

has not been studied adequately, but low-dose warfarin ther-

apy may be considered for patients at high risk of clotting.

Patients receiving therapy associated with an increased rate

of thrombosis should be educated about symptoms of VTE

and monitored closely. Prophylactic dose LMWH may be

useful for the prevention of thrombosis associated with thali-

dodmide therapy for multiple myeloma, whereas low-dose

warfarin, although used frequently, has not yet been shown

to be effective.

Future Directions

There are several exciting active areas of research in the

field of antithrombotic therapy. Many new agents are in

various stages of development. Modifications of existing

antithrombotic agents may serve to increase the predictabil-

ity of anticoagulant effect, improve bioavailability and con-

venience, and decrease complications. Combinations of

various antithrombotic agents are under investigation in an

attempt to improve efficacy while maintaining an acceptable

risk for hemorrhage.

Several classes of anticoagulants are under active inves-

tigation: inhibitors of the factor VIIa–tissue factor pathway,

factor Xa inhibitors, and direct thrombin inhibitors. One of

the most promising agents had been an orally active throm-

bin inhibitor, ximelegatran. The development of an orally

active agent with a more predictable anticoagulant response

would be a major advance over warfarin for the outpatient

management of thromboembolic disease. Ximelegatran is

metabolized to melagatran (the active agent), has a pre-

dictable anticoagulant response at a fixed dose, and does

not require monitoring. It had been shown to be effective

and safe for postoperative thromboprophylaxis and treat-

ment of VTE, atrial fibrillation, and acute coronary syn-

dromes (combined with aspirin). Unfortunately, liver

toxicity led to this drug being withdrawn from the market

worldwide in 2006.

In addition to new anticoagulants, attempts to augment

the naturally occurring anticoagulant pathway of protein C

and the fibrinolytic system may prove useful. Recombinant

activated protein C has been tested in patients with sepsis

and has been shown to decrease mortality; however, it may

increase the risk of bleeding. New antiplatelet agents, includ-

ing additional platelet GP IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors, are

also being studied.

While endeavoring to improve the benefit-risk ratio of

antithrombotic therapy, cost-effectiveness holds major

importance in the future of antithrombotic therapy. The

indications for antithrombotic therapy are continuously

expanding, and the cost of many new agents is very high.

It is important that any new antithrombotic drug be com-

pared with older, established therapies, with demonstra-

tion of definite advantage, before changing the standard

of care for patients with or at risk for thromboembolic

disease.

REFERENCES

Di Nisio M, Middeldorp S, Buller HR: Direct thrombin inhibitors.

N Engl J Med 2005;353:1028–40. [PMID: 16148288]

Ginsberg JS et al: Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechan-

ical heart valves. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:694–8. [PMID:

12639202]

Gurewich V: Ximelagatran: Promises and concerns. JAMA

2005;293:736–9. [PMID: 15701916]

Hirsh J et al: The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and

Thrombolytic Therapy: Evidence-based guidelines. Chest

2004;126:163–703S.

Hirsh J, O’Donnell M, Weitz JI: New anticoagulants. Blood

2005;105:453–464. [PMID: 15191946]

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

841

Kearon C et al: Comparison of low-intensity warfarin therapy with

conventional-intensity warfarin therapy for long-term prevention

of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med

2003;349:631–9. [PMID: 12917299]

Lee AY et al: Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for

the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in

patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:146–53. [PMID:

12853587]

Lee AY et al: Randomized comparison of low molecular weight

heparin and coumarin derivatives on the survival of patients with

cancer and venous thromboembolism. J Clin Oncol

2005;23:2123–9. [PMID: 15699480]

Lemoine NR: Antithrombotic therapy in cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:

2119–20. [PMID: 15699474]

McIntosh BA: Developing an algorithm for treating heparin-induced

thrombocytopenia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2004;2:216–22.

[PMID: 16163184]

Otzurk MA et al: Current debates in antiphospholipid syndrome:

The acquired antibody-mediated thrombophilia. Clin Appl

Thromb Hemost 2004;10:89–126. [PMID: 15094931]

Selleng K, Warkentin TE, Greinacher A: Heparin-induced thrombo-

cytopenia in intensive care patients. Crit Care Med

2007;35:1165–76.[PMID: 17334253]

Seshadri N et al: The clinical challenge of bridging anticoagulation

with low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with mechanical

prosthetic heart valves: An evidence-based comparative review

focusing on anticoagulation options in pregnant and nonpreg-

nant patients. Am Heart J 2005;150:27–34. [PMID: 16084147]

This page intentionally left blank

Index

A

Abacavir, 315t

Abciximab, 825

Abdominal trauma, 132–133

Abortion, septic, 813

Abruptio placentae, 820

Abscess

brain, 678

hepatic, 372t

intraabdominal, 177–179, 178f, 372t, 405

lung, 147–148, 148f

pancreatic, 179, 180, 350, 372t

periannular, 368

perinephric, 366

renal, 366, 368

soft tissue, 407, 408t

splenic, 368

Absence seizures, 663, 663t. See also Seizures

ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors

adverse effects, 497

after acute myocardial infarction, 509

for heart failure, 468, 471, 472, 510

nephrotoxicity, 316t

Acetaminophen poisoning/overdose, 771–773, 772f

Acetate, 123t

Acetazolamide, 66, 295

Acetylcysteine

for acetaminophen overdose, 772–773

for acute respiratory failure, 264

for inhalation injury, 746

Acetylprocainamide, 92t

Acid-base homeostasis

in acute renal failure, 331

buffering systems, 56–57

disorders, 58–59, 58t, 59f, 59t. See also Metabolic acidosis; Metabolic

alkalosis; Respiratory acidosis; Respiratory alkalosis

renal functions in, 57–58

respiratory function in, 58

Acinetobacter baumanii, 376t, 391

Acitretin, 624

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). See Human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease

Acticoat, 736

Activated charcoal, for poisonings, 756, 756t

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), 409, 411t

Activated protein C. See Drotrecogin alfa

Acute abdomen

clinical features, 697–698, 697t

controversies and unresolved issues

activated protein C and corticosteroids in sepsis, 701

bacterial translocation and enteral feedings, 701

laparoscopy, 702

monoclonal antibodies, 702

endoscopy, 699

imaging studies, 698–699

pathophysiology, 696

peritoneal lavage, 699

physiologic considerations, 696

postoperative, 699

specific pathologic entities

abdominal compartment syndrome, 701

cholecystitis. See Cholecystitis

colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome), 172,

355–356, 701

enteric fistula. See Gastrointestinal tract, fistulas

intraabdominal abscess. See Intraabdominal infections/abscess

small bowel obstruction. See Small bowel obstruction

treatment, 700

Acute arterial insufficiency

clinical features, 634–635, 634t, 635t

controversies and unresolved issues, 639

differential diagnosis, 636

general considerations, 632

imaging studies, 635

pathophysiology, 632–634, 633t

prognosis, 639

treatment

anticoagulation, 636

platelet-active agents, 636

rheologic agents, 636

supportive care, 638–639

surgery, 638

thrombin inhibitors, 636–637, 637t

thrombolytic agents, 637–638, 638t

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy, 809–810

Acute limb ischemia. See Acute arterial insufficiency

Acute lung injury (ALI), 296–297. See also Acute respiratory

dist

r

ess syndrome

Acute mesenteric ischemia

clinical features, 174, 649

differential diagnosis, 650

essentials of diagnosis, 648

general considerations, 648

imaging studies, 174–175, 175f, 649–650

pathophysiology, 174, 648–649

postoperative, 655

prognosis, 650–651

treatment, 650

Acute myocardial infarction

hypomagnesemia and, 49

non-ST-segment-elevation (non-STEMI)

clinical features, 503

essentials of diagnosis, 502

evaluation of stabilized patient, 503

general considerations, 502–503

treatment, 503–504, 505t

ST-segment elevation (STEMI)

clinical features, 506

complications, 509–512. See also Cardiogenic shock

differential diagnosis, 507

Page numbers followed by f or t indicate figures or tables, respectively.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

INDEX

844

Acute myocardial infarction, ST-segment elevation (STEMI) (Cont.):

essentials of diagnosis, 505

general considerations, 506

imaging studies, 506–507

treatment, 507–509

thyroid function in, 577–578

Acute radiation syndrome, 800–801

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

in acute pancreatitis, 348

acute renal failure in, 327t

barotrauma in, 163f, 166–167

clinical features, 299–301, 299t

controversies and unresolved issues

fluid management, 308

periodic lung recruitment, 309

prone positioning, 309

routine use of PV curves, 309

definition, 296, 296t

in diabetic ketoacidosis, 592–593

differential diagnosis, 301, 301t

essentials of diagnosis, 295

general considerations, 5t, 295–296

imaging studies, 160–161, 161f, 162f, 163f, 164f, 301

multiple organ system failure in, 299–300

pathophysiology, 296–298

physiologic manifestations

altered lung mechanics, 298–299, 299f

increased airway resistance, 299

refractory hypoxemia, 298, 298f

prognosis, 307–308

treatment

infection treatment and prevention, 307

mechanical ventilation

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, 306–307

inverse-ratio ventilation, 306

lower tidal volume strategy, 304–306, 304t, 305f

partial liquid ventilation, 307

pressure-controlled ventilation, 306

ventilator strategies and tactics, 274t

volume-present ventilation, 306

oxygen therapy, 302

pharmacologic therapy, 307

positive end-expiratory pressure, 302–304, 303f

reminders, 5t

supportive care, 307

Acute respiratory failure

in acute pancreatitis, 348

in ARDS. See Acute respiratory distress syndrome

in asthma. See Status asthmaticus

in COPD. See Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

hypercapnic

clinical features, 249, 249t

pathophysiology, 248–249, 249f

treatment considerations, 253–254

hypoxemic

clinical features, 249t, 252

pathophysiology, 250–252, 250t

treatment considerations, 254

in neuromuscular disorders. See Neuromuscular disorders

in obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, 311, 313

in obstructive sleep apnea. See Obstructive sleep apnea

oxygen delivery and tissue hypoxia in, 252–253

temperature and blood gases in, 253

in thoracic wall disorders. See Thoracic wall disorders

treatment. See also specific disorders

airway management

endotracheal intubation. See Endotracheal intubation

natural vs. artificial, 254

obstruction, 254

bronchodilators

anticholinergics, 261–262

beta-adrenergic agonists, 260–261

magnesium sulfate, 262–263

mechanisms of action, 260

theophylline, 262

chest physiotherapy, 264–265

corticosteroids, 263

expectorants, 264

leukotriene antagonists and inhibitors, 264

mechanical ventilation. See Mechanical ventilation

oxygen therapy

complications, 259–260

delivery devices, 258–259, 259t

inspired oxygen concentration, 257–258, 258f

oxygen saturation and oxygen content, 257, 257f

Pa

O

2

and P(

A

-a)

O

2

, 257

respiratory stimulants, 264

sedatives and muscle relaxants, 264

Acute tubular necrosis. See also Renal failure, acute

causes, 94t, 322t, 325

clinical features, 325

treatment, 325–326

Acyclovir, 315t, 627

Adenosine, 486

ADH (antidiuretic hormone), 23, 24–25

Adhesions, abdominal, 352

Adrenal insufficiency, acute

clinical features, 573–574

controversies and unresolved issues, 576

essentials of diagnosis, 572

general considerations, 572

pathophysiology, 572–573

treatment, 574–576, 575t

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH),

464, 574

Advance health care directive, 217

Adynamic ileus. See Ileus

AICD (automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator)

imaging studies, 143

presence in ICU patients, 491

for ventricular arrhythmias, 491

AIDS. See Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease

Air embolism, 141, 195, 199

Air plethysmography, 635

Aircraft, for critical care transport, 210

Airway management

artificial airways for, 101

endotracheal intubation for. See Endotracheal intubation

during interfacility transport, 211–212

intermediate airways for, 102

laryngeal mask airway for, 102

mechanical maneuvers, 101

INDEX

845

in prolonged mechanical ventilation, 103

surgical, 103

Airway resistance

anesthesia and, 99

in ARDS, 299

in mechanical ventilation, 268

Albendazole, for cysticercosis, 677

Albumin. See also Serum albumin

for hypovolemic shock, 229

for nephrotic syndrome, 76t

for nutrition support, 135

synthesis, 119

Albuterol

for acute respiratory failure, 260, 261

for hyperkalemia in renal failure, 42

for status asthmaticus, 537

Alcohol intoxication, 226

Alcoholic hepatitis, 131

Alcoholic ketoacidosis, 61t, 62

Aldosterone, in hypovolemic shock, 224

Aldosterone deficiency, 40

Alfentanil, 111t, 113

ALI (acute lung injury), 296–297. See also Acute respiratory

distress syndrome

Allergic reactions, transfusion-related, 83t

Alloimmunization, red blood cells, 80

Allopurinol, 316t

Alpha-adrenergic agents, 237, 241

Alpha

1

-antitrypsin concentrate, 76t

Alpha

2

-antiplasmin, 410t

Alteplase, 836t. See also Thrombolytic therapy

for acute arterial insufficiency, 637, 638t

for deep venous thrombosis, 646

for pulmonary embolism, 558

for stroke, 676, 676t

Altered mental status, in diabetic ketoacidosis, 584, 584f

Alveolar hypoventilation, 248

Ambulance transport, 209–210, 209t

Amebic meningoencephalitis, 677

American Burn Association, burn center referral guidelines, 724t

American Hospital Association, patient’s bill of rights, 215, 216t

Amikacin, 92t

Aminocaproic acid, 76t, 417, 524, 688

Aminoglycosides

nephrotoxicity, 315t

nutrient deficiencies caused by, 124t

once-daily dosing, 399

resistance to, 376t

Amiodarone

in acute myocardial infarction, 508

adverse effects, 496

for atrial fibrillation, 488

therapeutic ranges, 92t

for ventricular tachycardia, 491

Amlodipine, 501

Ammonium chloride, 124t

Amniotic fluid embolism, 811

Amphotericin B

for cryptococcal pneumonia, 604

electrolyte abnormalities and, 95

for hematogenously disseminated candidiasis, 389

hypokalemia and, 36

lipid formulations, 377–378

nephrotoxicity, 315t

protein binding, 89t

Ampicillin, 339t, 376t

Amplitude ratio, 191f, 192f

Amrinone, 244

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, 283

Anabolic steroids, 135

Anaerobic threshold, 223

Anaphylactic shock, 238–240, 239t

Anaphylactoid reactions, 239, 239t

Anaphylaxis, 562–564

Ancrod, 832

Anemia

chronic, 71–72

hemolytic, 73

sickle cell, 73

Anesthesia

airway effects, 97

cardiovascular effects, 97–98

hypothermia and, 100–101

inhaled, 97–100

intravenous agents, 114

regional, 98, 100

respiratory effects, 98–100

Aneurysms

great vessels

clinical features, 516

differential diagnosis, 516–517

essentials of diagnosis, 514

general considerations, 514–515, 515f

imaging studies, 516

treatment, 517

intracranial, rupture of. See Subarachnoid

hemorrhage

mycotic, 368

Angina pectoris

stable. See Myocardial ischemia

unstable. See Unstable angina pectoris

Angiodysplasia, 711

Angioedema, 564–565

Angiography

in acute arterial insufficiency, 635

in acute mesenteric ischemia, 175, 649

in aortic dissection, 516

cerebral, 684–685, 687

in lower gastrointestinal bleeding, 712

pulmonary. See Pulmonary angiography

Angiotensin receptor blockers, 316t

Anidulafungin, 378

Anion gap, 60. See also Metabolic acidosis

Anisindione, 835–836

Ankle-brachial index (ABI), 635

Ankylosing spondylitis, 286

Antacids, 124t

Anterior cord syndrome, 691, 693

Anti-D immune globulin, 76t

Antibiotics

for A. baumanii, 391

for burn wound infection, 737

INDEX

846

Antibiotics (Cont.):

for community-acquired pneumonia, 364–365, 365t

for COPD exacerbations, 292–293

for dialysis-related peritonitis, 339t

duration of treatment, 399

for extended-spectrum β-lactamases, 390–391

for group 1 β-lactamases, 391

guidelines for use, 376–378, 391–392

for infections in neutropenic patients, 374

for infective endocarditis, 368–369

for intraabdominal infections, 372t, 373

for methicillin-resistant S. aureus, 390

for necrotizing fasciitis, 371

nephrotoxicity, 315t

for nosocomial pneumonia, 381

prophylactic

for surgical infections, 397

in upper gastrointestinal bleeding, 709

resistance to, 376, 376t, 389–391

routes of administration, 399, 402

for sepsis, 362

for urinary catheter–associated infections, 383

for urinary tract infection, 367

for vancomycin-insensitive S. aureus, 390

for vancomycin-resistant enterococci, 389

for vancomycin-resistant S. aureus, 390

Anticholinergics

for acute respiratory failure, 261–262, 291–292

poisoning/overdose, 753t

for status asthmaticus, 537

Anticholinesterases, 110

Anticoagulants, in hemostasis, 410t

Anticoagulation therapy. See Antithrombotic therapy

Anticonvulsants, 665–666, 665t

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), 23, 24–25

Antifibrinolytic agents, 76t, 417, 524, 688

Antihistamines, 563, 565

Antihypertensives

after acute myocardial infarction, 509

after vascular surgery, 653–654

for hypertensive crisis, 481–482

nephrotoxicity, 316t

poisoning/overdose, 767–768

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, 839–840

Antiplatelet agents, 821–822

aspirin. See Aspirin

clopidogrel. See Clopidogrel

cyclooxygenase inhibitors, 822

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors. See Glycoprotein

IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors

nephrotoxicity, 316t

for stroke, 674

ticlopidine, 316t, 823–824, 824t

Antipsychotics

atypical, for delirium, 435

Antithrombin, 410t

Antithrombin II concentrate, 76t

Antithrombotic therapy

for acute arterial insufficiency, 636

anisindione, 835–836

anticoagulants

defibrinating agents, 832

direct thrombin inhibitors, 831

indirect thrombin inhibitors, 831–832

low-molecular-weight heparin. See Low-molecular-weight

heparin

unfractionated heparin. See Unfractionated heparin

warfarin. See Warfarin

in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, 839–840

antiplatelet agents, 821–822

aspirin. See Aspirin

clopidogrel. See Clopidogrel

cyclooxygenase inhibitors, 822

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors. See Glycoprotein

IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors

nephrotoxicity, 316t

ticlopidine, 316t, 823–824, 824t

in canc

er patients,

840

in continuous renal replacement therapy, 341–342

for deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

prophylaxis, 644–645

treatment, 554–557, 645, 646t

defibrinating agents, 832

dextrans. See Dextrans

future directions, 840

in hemodialysis, 337

phosphodiesterase III inhibitors, 532, 825

physical measures, 558, 561, 647, 821

in pregnancy, 827t, 838–839, 839t

in stroke, 674

for unstable angina or non-STEMI, 504, 505t

Antithyroid drugs, 568, 568t

Antituberculosis drugs, 603

Antivenin, 796

Anxiety and fear, 433, 438–440, 439t

Aortic dissection

classification, 515–516

clinical features, 483–484, 516

DeBakcy classification, 515

differential diagnosis, 516–517

essentials of diagnosis, 483

etiology, 515

general considerations, 483

imaging studies, 484–485, 484f, 485f, 516

Stanford classification, 515

treatment, 485, 517

Aortic regurgitation, 198, 475

Aortic stenosis, 475

Aortic surgery, 655, 656

Aortic transection, 515

APACHE (Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation)

score, 12

Apnea threshold, 99

Aprotinin, 424

aPTT (activated partial thromboplastin time), 409, 411t

Arachidonic acid, 231, 231f, 232t

ARDS. See Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Argatroban

for acute arterial insufficiency, 636–637, 637t

for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, 645, 829t

mechanisms of action, 831

Arginine vasopressin (AVP). See Antidiuretic hormone