Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRITICAL CARE ISSUES IN PREGNANCY

817

Investigations have shown, however, that the average blood

loss after vaginal delivery is near 500 mL, whereas that fol-

lowing cesarean section is in excess of 1 L. The working

definition of postpartum hemorrhage therefore is relative.

Most would acknowledge the presence of postpartum hem-

orrhage when blood loss exceeds 1 L, when there is a 10%

change in the hematocrit between admission and postpar-

tum determinations, or when transfusion is necessary.

The most common causes of early postpartum hemorrhage

(<24 hours after delivery) are uterine atony, lower genital tract

lacerations, and retained products of conception. Less common

causes include placenta accreta, uterine rupture, inversion of

the uterus, and coagulopathies. Uterine atony is by far the most

common and may be associated with the antepartum use of

oxytocin or with uterine overdistention from multiple gesta-

tion or polyhydramnios. Other factors thought to be associated

with uterine atony include high parity, prolonged labor,

cesarean section, precipitous labor, chorioamnionitis, and the

use of tocolytic agents (especially magnesium sulfate).

Lower genital tract lacerations occur frequently and usu-

ally present with vaginal bleeding immediately after delivery.

Uterine lacerations can bleed into the peritoneal cavity or

retroperitoneal space and therefore do not always present

with vaginal hemorrhage. Factors associated with lower gen-

ital tract lacerations are forceps or vacuum delivery, fetal

macrosomia or malpresentation, and precipitate delivery.

Failure of the placenta to completely separate is a risk fac-

tor for the development of both uterine atony and postpar-

tum hemorrhage presumably owing to the placental

fragments interfering with the normal contraction of the

uterus that is necessary for hemostasis. Retention of a suc-

centuriate lobe (accessory lobe of the placenta) may present

with postpartum hemorrhage in the early postpartum

period. Placenta accreta also may cause life-threatening hem-

orrhage owing to the inability of the placenta to completely

separate from the uterine wall. Risk factors for placenta acc-

reta include previous puerperal curettage or previous uterine

surgery, including cesarean section, and placenta previa.

Uterine rupture is an uncommon but catastrophic cause

of postpartum hemorrhage. Because uterine artery blood

flow is between 500 and 600 mL/min, hemorrhage from this

cause can result in rapid maternal exsanguination. Conditions

thought to predispose to uterine rupture include previous

uterine surgery, breech extraction, obstructed labor, abnor-

mal fetal position, and high parity.

Uterine inversion is also a rare complication of delivery,

although it may recur in a patient’s subsequent pregnancies.

Uterine inversion is most remarkable for the development of

shock out of proportion to the amount of blood lost.

Coagulopathies frequently are associated with postpar-

tum hemorrhage. They often occur in association with other

complications of pregnancy such as abruptio placentae,

retained dead fetus, and amniotic fluid embolism. In addi-

tion, preexisting chronic coagulation disorders are signifi-

cant contributors to postpartum hemorrhage.

Delayed postpartum hemorrhage occurring between

24 hours and 6 weeks after delivery may require admission to

the ICU for resuscitation, observation, and perioperative

care. Common causes include infection, placental site subin-

volution, and retained products of conception, as well as

underlying coagulopathy.

Clinical Features

Although the initial management of postpartum hemorrhage

will be accomplished in the delivery room, the ICU physician

should be familiar with the basic principles of diagnosis and

early management. The first priority is to establish the cause.

The relationship between the onset of hemorrhage and the

time of delivery is critical in establishing the diagnosis.

Bleeding prior to delivery of the placenta often indicates a

genital tract laceration, a coagulopathy, or a partial separation

of the placenta. When bleeding begins after the placenta is

delivered, uterine atony, uterine inversion, retained fragments

of the placenta, or placenta accreta may be responsible. The

placenta should be inspected to ensure that torn vessels are

not present, which might indicate the presence of an acces-

sory lobe; that appropriate contour is observed; and that por-

tions are not missing (suggesting placenta accreta).

Uterine atony requires fundal massage and the adminis-

tration of ecbolic drugs (see next). Lacerations should be

sutured in a manner that allows closure of the wound and

compression of the underlying vessels. Hematomas may

form as the result of lacerations. Hematomas below the

pelvic diaphragm usually are accompanied by severe pain

and a palpable mass. Sudden onset of shock without signifi-

cant apparent blood loss suggests that the bleeding point is

above the pelvic diaphragm.

A coagulopathy is suggested by the presence of bleeding

from remote locations such as intravenous insertion sites.

The diagnosis of coagulopathy may be made rapidly by

observing a tube of the patient’s blood for clot formation. If

a firm clot forms within 5 minutes, it is unlikely that clini-

cally significant hypofibrinogenemia is present.

Treatment

A. General Measures—Postpartum hemorrhage represents

a special cause of hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock. A sta-

ble airway and adequate intravenous access must be ensured.

Initial resuscitation should be with balanced salt solutions,

although blood replacement will be required early if hemor-

rhage cannot be arrested. Packed red blood cells are usually

used. In the event of severe hemorrhage, replacement of clot-

ting factors also may be needed via the use of fresh-frozen

plasma. Fresh-frozen plasma should be given only if labora-

tory testing shows that the patient has developed a coagu-

lopathy. Blood should be warmed to prevent hypothermia.

Arterial blood gas and hemoglobin determinations should

be performed regularly during resuscitation and after control

of bleeding. Measurements of blood pressure, pulse rate, and

CHAPTER 38

818

urine output will help to assess volume status. Pulmonary

artery catheters are seldom required, although a central

venous catheter may be helpful in actively bleeding patients

who require ongoing resuscitation and transfusion.

B. Ecbolic Agents—Hemorrhage from uterine atony should

be managed with fundal massage plus an intravenous infusion

of oxytocin (10–40 units/L of normal saline). If oxytocin does

not arrest the hemorrhage, treatment with either methyler-

gonovine (0.2 mg intramuscularly) or carboprost

tromethamine (15-methylprostaglandin F

2α

), 0.25 mg intra-

muscularly, may be used. Misoprostol (800 mg per vagina or

rectum) also may be effective. Methylergonovine may be asso-

ciated with an increase in maternal blood pressure and should

not be used in the patient with hypertension. Prostaglandin

agents may provoke bronchospasm and should be not be

used in patients with significant asthma.

C. Surgery—When postpartum hemorrhage cannot be con-

trolled by massage and ecbolic agents, emergent surgery usu-

ally is required. In many cases, these procedures will have

been performed before the patient is transferred to the ICU.

Occasionally, however, a previously stable patient will require

exploration for hemorrhage after it has been controlled.

Common surgical procedures include evacuation of

hematomas caused by lacerations (combined with suturing

of the injury and control of the bleeding vessel), ligation of

pelvic arterial vessels, packing, and hysterectomy. Recent

reviews of cesarean hysterectomy reveal that the average

blood loss for this procedure when done emergently was

3000 mL, and the most common antecedent complications

were uterine rupture, placenta accreta and uterine atony.

D. Angiographic Embolization—When bleeding continues

from an identifiable localized area, embolization via a radi-

ographically placed catheter may be extremely helpful. Some

authors have described the placement of embolization

catheters prophylactically in patients at highest risk of post-

partum hemorrhage.

E. Delayed Postpartum Hemorrhage—Fewer than 1% of

patients with postpartum hemorrhage present more than 24

hours after delivery. Infection and retained products of concep-

tion are the most common causes, with subinvolution of the

placental site also being a consideration. Uterine curettage

should be performed only when retained products of concep-

tion are suspected because of the risk of intrauterine adhesions.

Pelvic and uterine ultrasonography may be helpful in determin-

ing whether retained products are present, although all postpar-

tum uteri contain some clot and debris. Even when there is not

retained placental tissue, evacuation of intrauterine clots allows

more efficient uterine contraction and often results in hemosta-

sis. Estrogens may be used to improve endometrial regrowth

after curettage and to avoid intrauterine adhesions. Ecbolic

agents and antibiotics may be given if retained products of con-

ception are not present. If hemorrhage persists more than 12–24

hours, the patient should undergo curettage for presumed

retained products, even in the absence of a definite diagnosis.

Jansen AJ et al: Postpartum hemorrhage and transfusion of blood

and blood components. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2005;60:663–71.

[PMID: 16186783]

Oyelese Y, Smulian JC: Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa

previa. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:927–41. [PMID: 16582134]

Tamizian O, Arulkumaran S: The surgical management of post-

partum haemorrhage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2002;16:81–98. [PMID: 11866499]

Trauma During Pregnancy

Accidental injury occurs in approximately 1 in 12 pregnancies.

While many of these incidents are minor, one should bear in

mind that two patients are at risk. Serious injuries during preg-

nancy do not result in a higher maternal mortality rate than do

similar injuries in a nongravid patient. Fetal death, however, is

common, with fetal loss rates of up to 61% reported in studies

of severe trauma. Eighty-five percent of all maternal deaths

from trauma are due to closed head injuries and hemorrhagic

shock, whereas fetal deaths result from abruptio placentae as

well as maternal death and fetal hypoxia. Because of this com-

bined risk, and because of the risk of preterm labor, pregnant

patients often require inpatient observation.

The physiologic changes of pregnancy make the patient

both more and less susceptible to the effects of trauma. The

increased plasma volume and decreased hematocrit further

the potential for diminished oxygen delivery following

blood loss. Fluid resuscitation requirements after hemor-

rhage are greater because of the 50% increase in maternal

intravascular volume. Conversely, the increased blood vol-

ume makes the mother more tolerant of blood loss without

change in her vital signs. The increase in maternal heart rate

(15–20 beats/min) and the decrease in both systolic and

diastolic blood pressures (10–15 mm Hg) may confound

attempts to evaluate volume replacement. Furthermore, an

elevation of coagulation factors during pregnancy increases

the risk for thrombogenesis with surgery or prolonged

immobilization.

As pregnancy progresses into the second trimester, fetal

growth distends the uterus upward into the abdomen, where

it becomes more susceptible to direct injury. The bladder also

becomes more prone to injury, especially after the twelfth

week of gestation. Because blood flow to the uterus is abun-

dant (as much as 600 mL/min), direct injury to the uterus

may cause rapid exsanguination. Uterine blood vessels lack

autoregulation, so maternal shock causes a substantial

decrease in fetal oxygen delivery. Uterine blood flow may fall

before maternal shock becomes manifest and may result in

fetal hypoxia in the face of normal maternal vital signs. Fetal

responses to decreased perfusion and hypoxia include alter-

ations in heart rate (bradycardia or tachycardia), loss of heart

rate variability, and repetitive late decelerations.

Motor vehicle accidents are the principal cause of acci-

dental injuries during pregnancy and account for about 50%

of all cases of blunt abdominal trauma, but 82% of injuries

CRITICAL CARE ISSUES IN PREGNANCY

819

resulting in fetal death. Three-point-restraint seat belts are

preferable for pregnant passengers because the incidence of

body flexion and uterine compression is less than that

induced by lap belts alone. Placental abruption is the most

common cause of fetal demise after blunt abdominal trauma.

Abruption is caused by deformation of the elastic uterus

around the inelastic placenta. The shearing force thus pro-

duced tears the decidua basalis. Current evidence indicates

that the position of the placenta does not influence the devel-

opment of abruption. Uterine rupture is uncommon and

probably occurs in less than 0.6% of all traumatic injuries

during pregnancy. It carries a maternal death rate of less than

10%, but a fetal death rate of nearly 100%. Maternal pelvic

fractures occur frequently but do not necessarily preclude

subsequent vaginal delivery. Such fractures are of concern

when they are comminuted and badly displaced because they

carry the potential to injure the uterus and fetus. Placental

abruption and pelvic fractures are highly correlated.

Gunshot wounds are the most common type of penetrat-

ing injury sustained by pregnant patients. Regrettably, inci-

dents occur in which there was clear intent to harm the fetus.

When compared with nonpregnant victims, pregnant

patients actually have a lower mortality rate after abdominal

gunshot wounds, perhaps because the enlarged uterus and its

contents protect the patient by absorbing and dissipating the

missile’s kinetic energy. Upper abdominal gunshot and stab

wounds, however, cause a higher incidence of intestinal

injury because of cephalad displacement of the viscera by the

uterus. Direct injury of the fetus by a bullet occurs in 70% of

cases, with a 65% intrauterine fetal death rate. Maternal

death is much less common.

Burns, electrocution, and suicide attempts are less com-

mon causes of injury. Unless a burn covers more than 30% of

the patient’s body surface area, it generally will not affect the

pregnancy. Fetal outcome is probably related to gestational age

at the time of the burn. The highest mortality rate is recorded

during the first trimester. Topical iodine solutions should be

avoided because large amounts may be absorbed through

the burn wound. House current electrical injuries occur

uncommonly but may be associated with a high fetal mor-

tality rate because of the path of the current through the

patient’s body. Pregnant victims of electrocution may report

a reduction in fetal movements immediately after the incident.

Fetal demise or intrauterine growth retardation may follow.

Oligohydramnios has been reported at the time of delivery.

Management

A. General Principles—Pregnant patients who require ICU

admission following injury commonly will be resuscitated

and stabilized in the emergency department. Initial treat-

ment in the ICU may be advisable, however, because of the

availability of invasive monitoring.

On arrival, initial concern must be directed toward the

mother, with attention paid to establishment of an adequate

airway, breathing, and circulation. The patient should lie in

the left lateral position, if possible, to prevent compression of

the vena cava by the gravid uterus. Both maternal hypoten-

sion and fetal hypoxia may result from caval compression. If

concern about the cervical spine precludes the decubitus

position, an assistant should displace the uterus by hand to

the left in an attempt to decompress the vena cava.

Alternatively, the entire bed or support board can be tilted.

Supplemental oxygen should be given to increase oxygen

delivery to the fetus. Upper extremity intravenous catheters

should be placed to ensure adequate intravenous access. A

nasogastric tube should be inserted during the early stages of

resuscitation to allow gastric decompression and prevent

aspiration. In the presence of a viable fetus, continuous fetal

heart rate monitoring should be instituted as soon as possible.

Blood is preferred as the initial fluid for resuscitation of

hypotensive trauma patients. Particular attention must be

paid to Rh compatibility. If Rh-incompatible blood is inad-

vertently given to an Rh-negative woman, anti-D antibody

should be given in a dose of 300 mg for every 30 mL of whole

blood or 15 mL of packed red blood cells transfused.

Pregnant patients require more volume replacement than do

nonpregnant patients because of their physiologically

expanded intravascular space.

A bladder catheter should be placed as soon as possible

both to measure the urine output and to help establish the

integrity of the urethra and bladder. Urine so obtained

should be inspected for gross blood and tested for micro-

scopic hematuria.

Normal physical signs of abdominal injury such as pain

and loss of bowel sounds may be masked by the pregnant

uterus. Conversely, all these findings may be produced by the

pregnancy itself. Vaginal bleeding generally is considered an

ominous sign because it may signal placental abruption or

severe pelvic injury.

B. Laboratory Studies—Studies should include hemoglo-

bin serum electrolytes, coagulation profile, amylase, and

blood crossmatch. Routine arterial blood gases are advisable.

When placental separation is suspected because of a pelvic

fracture, fetal distress, uterine tetany, or vaginal bleeding,

measurements of blood fibrinogen concentration, fibrin

degradation products, and platelet count are of particular

importance. Additionally, a tube of blood should be obtained

and observed for clot formation. Noncoagulable blood indi-

cates probable placental abruption and mandates immediate

replacement of fibrinogen with fresh-frozen plasma or cryo-

precipitate, followed by evacuation of the uterus. The possi-

bility of fetomaternal hemorrhage should be evaluated with

a Kleihauer-Betke study. Fetomaternal hemorrhage is most

common when the placenta is located anteriorly, when pelvic

tenderness is present, and following motor vehicle accidents.

If severe, it can result in fetal anemia or fetal death.

C. Imaging Studies—Critical radiographic studies should

not be withheld in an attempt to avoid fetal x-ray exposure.

The fetal risks from various doses of x-ray and the expected

CHAPTER 38

820

doses from various procedures were discussed previously.

The need for chest and abdominal x-rays should be guided

by the nature and severity of the injury. Free air under the

diaphragm on an upright chest x-ray is an indication for

immediate laparotomy. Traumatic separation of the pubic

symphysis in or after the second trimester is difficult to

detect on x-ray because of the normal ligamentous laxity that

accompanies pregnancy. Maternal and fetal complications

are more common after pelvic fractures, and their presence

must be identified.

Obstetric ultrasound should be performed in all cases of

trauma during pregnancy. It is helpful in diagnosing a retro-

placental clot, although absence of a visible clot on ultra-

sound cannot rule out placental abruption. Additionally,

ultrasound can aid in estimating gestational age when a his-

tory cannot be obtained.

D. Peritoneal Lavage—Open peritoneal lavage through a

supraumbilical incision is an excellent technique for diag-

nosing abdominal injuries. Approximately 1 L of lavage fluid

is instilled through the small incision and allowed to return

passively to the container. Criteria that constitute a positive

lavage include (1) a red blood cell count of more than

100,000/μL, (2) a white blood cell count of more than

500/μL, (3) the presence of GI contents, bile, or bacteria, and

(4) increased amylase.

E. Fetal Monitoring—Immediately on patient arrival in the

ICU, fetal heart monitoring should be instituted. Such mon-

itoring provides information about both the fetus and the

mother. The fetus may be compromised by hypoxia before

the mother becomes hypotensive. Bradycardia, tachycardia,

and loss of beat-to-beat variability are ominous signs.

Monitoring in gestations beyond 18–20 weeks may be able to

predict abruptio placentae. Although intermittent ausculta-

tion is possible, it should not substitute for electronic surveil-

lance. The gestational age at which monitoring is mandatory

is controversial, but all authorities would monitor potentially

viable fetuses (>22–23 weeks). Monitoring necessitates the

presence in the ICU of personnel experienced in the inter-

pretation of fetal heart rate patterns.

F. Tocodynamometry (Uterine Contraction Monitoring)—

Tocodynamometry is of significant importance in predicting

early placental abruption. The incidence of abruption

increases with frequent uterine activity (more than eight

uterine contractions per hour), and about 25% of trauma

patients with at least three uterine contractions in a 20-

minute period suffered either abruptio placentae or preterm

labor. Another study found that these complications did not

occur in patients who were without contractions for the first

4 hours. Monitoring during the first 4–6 hours after admis-

sion therefore has been proposed, with additional monitor-

ing only in patients with contractions on initial monitoring

or with a change in maternal condition.

G. Surgery

1. Trauma—Certain kinds of trauma must be managed

operatively. Bowel injuries must be repaired, fractures

reduced, and wounds closed. Pregnancy should not delay or

contraindicate surgical exploration.

2. Abruptio placentae—Evacuation of the uterus is indi-

cated for placental abruption. If gestation has continued for

more than 30 weeks, immediate cesarean section may save

both the fetus and the mother. In cases of intrauterine fetal

demise, labor and spontaneous vaginal delivery may occur.

Caution must be exercised to detect DIC, which is more

common after extensive abruption. If both the platelet count

and the fibrinogen concentration decline, fresh-frozen

plasma or cryoprecipitate should be given and a hysterotomy

performed if delivery is not imminent. The coagulopathy

usually ceases when the placenta is removed.

3. Uterine rupture—Shock, severe abdominal pain, and

lack of fetal heart tones suggest uterine rupture. It may be

difficult to localize the fundus of the uterus, and fetal parts

may be easily palpable through the abdominal wall. An

abdominal x-ray usually shows that the fetal skeleton is in an

unusually high location in the abdomen. Peritoneal lavage is

always positive for blood and returns more fluid than was

instilled (amniotic fluid). At surgery, massive bleeding may

have to be controlled with bilateral internal iliac artery liga-

tion. Supracervical hysterectomy may be required.

4. Cesarean section—Adequate exposure of abdominal

injuries usually can be achieved with careful mobilization of

the uterus. Cesarean section may be required, however, when

the gravid uterus prevents access to deep pelvic injuries.

Patients with undisplaced pelvic fractures usually do not

require cesarean section.

Premature separation of the placenta and fetal head

injuries both may be consequences of maternal trauma dur-

ing pregnancy. Placental separation coexisting with a living

fetus often mandates an emergent cesarean section. In the

case of a live fetus undergoing labor after maternal trauma,

consideration should be given to fetal ultrasound for evi-

dence of fetal head injury. If such evidence exists, this fetus

also may benefit from cesarean delivery.

Cusick SS, Tibbles CD. Trauma in pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin

North Am 2007;25:861–72, xi. [PMID: 17826221]

El-Kady D et al: Trauma during pregnancy: An analysis of mater-

nal and fetal outcomes in a large population. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2004;190:1661–8. [PMID: 15284764]

Mattox KL, Goetzl L: Trauma in pregnancy. Crit Care Med

2005;33:S385–9. [PMID: 16215362]

Muench MV, Canterino JC. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol

Clin North Am 2007;34:555–83, xiii. [PMID: 17921015]

Weiss HB, Songer TJ, Fabio A: Fetal deaths related to maternal

injury. JAMA 2001;286:1863–8. [PMID: 11597288]

821

0039

Antithrombotic Therapy

Elizabeth D. Simmons, MD

Pathologic blood clot formation within blood vessels

(thrombosis) and embolization of clots to distant sites result

from complex interactions among platelets and coagulation

proteins, the fibrinolytic system, and the blood vessel itself.

Thrombi are composed of red blood cells, platelets, and fib-

rin in varying proportions depending on the conditions

present at the site of thrombus formation. Very diverse clini-

cal conditions are associated with increased risks of such

pathologic thrombosis and embolization (Table 39–1).

Thromboembolic disease is a major cause of morbidity and

mortality; 30–40% of all deaths in the United States are

attributed to thrombotic events, and nonfatal events occur in

hundreds of thousands of people each year.

Antithrombotic therapy consists of strategies (both phar-

macologic and physical) to prevent pathologic blood clot

formation or to treat established thromboses in order to

limit the clinical consequences of such clots. The decision to

use antithrombotic therapy in clinical practice is often com-

plicated because of the diversity of the clinical conditions

affecting patients, difficulties in establishing accurate diag-

noses of thromboembolism, and our still incomplete under-

standing of the risks and benefits of antithrombotic therapy

in the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disease.

Numerous new pharmacologic agents have been developed

or are under development, and various combinations of

antithrombotic agents are being used in diverse settings.

Physical Measures

Venous stasis and damage to blood vessels are the two most

important risk factors for the development of venous throm-

boembolism (VTE). Physical measures to decrease venous

stasis are quite important in preventing venous clots, particu-

larly in hospitalized patients. Limiting bed rest as much as

possible for most medical patients and early mobilization

after surgery can decrease the period of risk for venous throm-

bosis. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices (IPCs) and

the venous foot pump (VFP) reduce venous stasis, increase

venous flow, and reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis

(DVT) in lower-risk patients but have not been demonstrated

to reduce the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE). These devices

are used primarily in patients with high bleeding risk or in

combination with pharmacologic agents for prevention of

VTE. IPCs should not be used in the presence of established

thrombosis, severe peripheral vascular disease, skin ulcers, or

after leg trauma if there is compromised tissue viability.

Graduated compression stockings may help to control leg

edema but are not highly effective for the prevention of VTE.

They are not recommended as an isolated measure for preven-

tion of VTE in patients at moderate to high risk.

Interruption of the inferior vena cava using a fluoroscop-

ically placed filter is indicated for treatment of patients with

lower extremity venous thrombosis who have a major con-

traindication to anticoagulant therapy or for patients with

recurrent thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagula-

tion. Inferior vena cava filter placement reduces the risk of PE

but does not prevent recurrence or extension of lower

extremity thromboses. Therefore, unless contraindicated, ini-

tiation of anticoagulation as soon as possible after filter place-

ment is advised.

Surgical or transvenous embolectomy is performed occa-

sionally in selected patients with life-threatening thromboem-

bolic disease, particularly in patients with contraindications to

anticoagulation or thrombolysis.

Antiplatelet Agents

Antiplatelet therapy (alone or in combination with anticoag-

ulants) is most beneficial in prevention or treatment of arte-

rial thrombosis. Arterial thrombi usually develop in

abnormal blood vessels and are associated with activation of

both blood coagulation and platelets; however, arterial

thrombi are composed primarily of platelets held together by

fibrin strands. Antiplatelet agents inhibit platelet function

through several biochemical pathways or by exerting effects

on the platelet membrane.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 39

822

Antiplatelet agents are useful in the management of

patients with unstable angina; suspected acute myocardial

infarction; a history of myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke,

transient ischemic attacks, or peripheral vascular disease; and

those undergoing vascular procedures. Antiplatelet agents are

not as useful as other measures for prevention of VTE, such as

anticoagulation, particularly in high-risk surgical patients or

for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenase (Aspirin,

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents)

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is a key enzyme in the prostaglandin

pathway within platelets and endothelial cells. The final prod-

uct of this pathway differs in platelets and endothelial cells.

Thromboxane A

2

(TXA 2), a potent inducer of platelet aggre-

gation, is produced in platelets, whereas prostacyclin, an

inhibitor of platelet aggregation, is produced in endothelial

cells. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX (COX-1 more so than

COX-2), which cannot be resynthesized by platelets because

they have no nucleus. Vascular prostacyclin production is

affected to a much lesser extent by aspirin because endothelial

cells can resynthesize cyclooxygenase, and because prostacy-

clin is also COX-2–derived, which is much less sensitive to

inhibition by aspirin. Thus aspirin is an ideal pharmacologic

agent for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolic

disease. Several of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs) also inhibit platelet COX, but inhibition is

reversible. NSAIDs may cause clinical bleeding in patients

with underlying hemostatic defects or after invasive proce-

dures, but they are generally not used therapeutically for treat-

ment or prevention of thromboembolic disorders. COX-2

inhibitors do not inhibit production of platelet TXA 2 and do

not have antithrombotic properties; these agents actually may

increase the risk of thromboembolism.

Three reversible COX inhibitors (ie, indobufen, flur-

biprofen, and triflusal) that may have beneficial effects simi-

lar to those of aspirin have been investigated as alternatives

to aspirin; none are currently approved for use in the United

States, and it is unclear whether they will prove to have any

advantage over currently available treatments.

Aspirin is rapidly and completely absorbed from the GI

tract, metabolized to salicylate, and circulates as salicylate

bound primarily to albumin. Salicylate is metabolized in the

liver and excreted in the urine. The serum half-life of salicy-

late is 15–20 minutes. The effect of aspirin on platelet func-

tion begins within 1 hour of ingestion (3–4 hours for

enteric-coated preparations) and lasts the life of the platelet

(8–10 days). Enteric-coated tablets should be chewed if rapid

antiplatelet effect is necessary. Gastric irritation may be

reduced with enteric-coated and timed-release forms of

aspirin, but absorption may be reduced or delayed.

Ingestion of aspirin in doses commonly used in clinical

practice prolongs the bleeding time in normal subjects some-

what variably, typically by 1–3 minutes, and out of the normal

range only in about half of subjects. Aspirin inhibits platelet

aggregation in vitro, but these laboratory effects do not corre-

late well with in vivo hemostasis. In patients with underlying

hemostatic defects (eg, hemophilia, von Willebrand disease,

uremia, mild preexisting disorders of platelet function, and

thrombocytopenia), aspirin may markedly prolong the bleed-

ing time and cause serious bleeding.

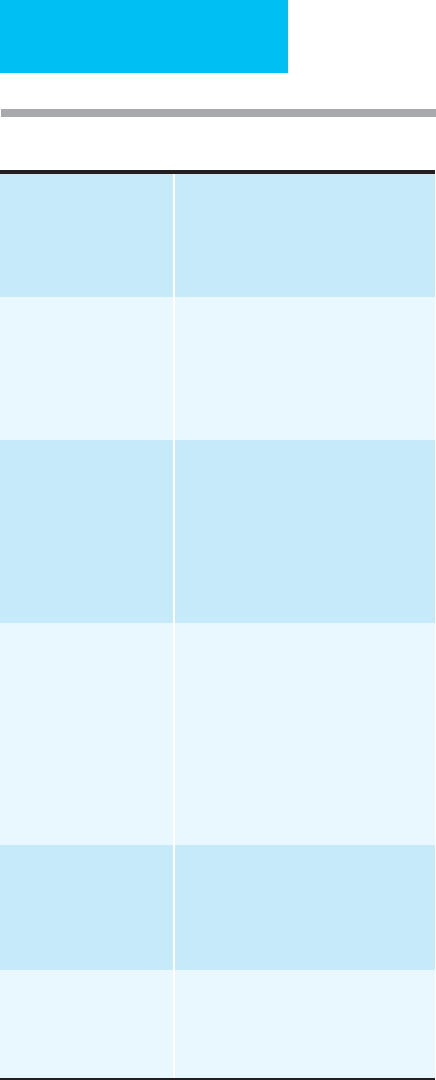

Stasis Immobilization

Congestive heart failure

Surgery

Advanced age

Obesity

Atrial fibrillation

Blood vessel abnormalities Trauma, coronary artery disease, peripheral

vascular disease, varicosities, vasculitis,

artificial surfaces (vascular grafts, heart

valves, indwelling catheters), diabetes

mellitus

Homozygous homocystinuria

Previous thrombosis

Abnormalities of

physiologic

antithrombotic

mechanisms

Antithrombin deficiency

Protein C or S deficiency

Hereditary resistance to activated protein C

(factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene

mutation G20210A)

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

(MTHFR) gene mutation C677T

Defective or deficient plasminogen

Plasminogen activator deficiency

Abnormalities of

coagulation and

fibrinolysis

Malignancy

Pregnancy

Oral contraceptives

Hormone replacement therapy

Tamoxifen

Nephrotic syndrome

Lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid

antibody syndrome

Prothrombin complex concentrate solution

Dysfibrinogenemia

Factor VIII >150%

Abnormalities of platelets Myeloproliferative disorders

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Hyperlipidemia

Diabetes mellitus

Heparin-associated thrombocytopenia

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Hyperviscosity Polycythemia

Leukemia

Sickle cell disease

Leukoagglutinin

Hypergammaglobulinemia

Table 39–1. Conditions associated with pathologic

thromboembolism.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

823

The clinical benefits of aspirin have been established by

large trials of patients with various thromboembolic phenom-

ena, with endpoints including development of thrombosis,

death from thrombosis, and bleeding complications.

Laboratory tests of platelet function are not useful for monitor-

ing such patients in clinical practice. The measurable

antiplatelet effects of aspirin are equivalent over a wide range of

daily aspirin dosage (300–3600 mg/day), and the therapeutic

benefits have been demonstrated with as little as 75 mg/day (or,

in one study, 30 mg/day). The minimum effective dose varies for

different disorders, but for most situations, a daily dose between

50 and 100 mg is effective and minimizes toxicity with long-

term use. In acute myocardial infarction and acute ischemic

stroke, a dose of 160 mg/day reduces early mortality and recur-

rent events. Higher-dose aspirin (eg, 650–1500 mg/day) does

not improve outcome and actually may be detrimental.

Currently available data support the use of aspirin in car-

diovascular disease prevention, stable and unstable angina,

acute myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attacks and

incomplete stroke, severe carotid stenosis, stroke following

carotid artery surgery, and in patients with prosthetic heart

valves (in combination with oral anticoagulation). The ben-

efits of aspirin following vascular or valve surgery, arterial

procedures, or creation of fistulas or shunts are less certain

but appear to include a reduction in risk of arterial occlusion

compared with no therapy. Aspirin, although more effective

than placebo, is less effective than anticoagulation in pre-

venting recurrent stroke associated with nonvalvular atrial

fibrillation. Aspirin has not been shown to be effective for

treatment of established VTE and is inferior to other meas-

ures for prevention of VTE, especially in high-risk patients.

Although one large trial showed a benefit of aspirin—alone

or in combination with anticoagulation—for patients under-

going hip surgery, it is less effective than anticoagulation.

The safety and efficacy of aspirin in combination with

anticoagulants have not been clearly established.

Aspirin resistance resulting in treatment failure has been

observed in some patients receiving aspirin for the treatment of

ischemic vascular disease. The mechanisms underlying resist-

ance are not known, and there is currently no reliable platelet

function test to predict which patients are unlikely to benefit

from aspirin. Concomitant therapy with other NSAIDs can

reduce the antiplatelet effect of aspirin because of competition

for binding sites in the platelet and may be one important

mechanism of aspirin treatment failure because of widespread

use of these over-the-counter medications. Patients who

develop recurrent ischemic events despite aspirin are candi-

dates for alternative antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation.

Adverse effects of aspirin include dose-dependent GI irrita-

tion (eg, dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting, occult blood loss, and

gastric ulceration), hypersensitivity reactions, abnormal liver

function tests (rare), nephrotoxicity (rare), and at high doses,

tinnitus and hearing loss. Enteric-coated aspirin does not

reduce the risk of GI bleeding compared with regular aspirin.

Concomitant use of NSAIDs may increase the risk of GI bleed-

ing. Omeprazole is effective at treating and preventing GI ulceration

and bleeding associated with NSAIDs and may permit chronic

use of aspirin in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events

who have had this complication. Overdosage of aspirin (salicy-

late intoxication) may be life-threatening and is manifest by

metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis, dehydration, fevers,

sweating, vomiting, and severe neurologic symptoms. Reye’s

syndrome in infants and children appears to be associated with

aspirin usage. In patients at risk for major bleeding, the

antithrombotic effects of aspirin may result in serious bleeding.

High doses of aspirin may result in interference with prothrom-

bin synthesis, prolongation of the prothrombin time, and signif-

icant hemorrhagic sequelae. Subarachnoid hemorrhage may

occur with the use of more than 15 aspirin per week, particu-

larly in older or hypertensive women.

Inhibitors of ADP-Mediated Platelet Aggregation

(Ticlopidine, Clopidogrel)

Ticlopidine and clopidogrel are structurally related

thienopyridines that inhibit platelet function. Repeated daily

dosing results in cumulative inhibition of ADP-induced

platelet aggregation and slow recovery of platelet function

after stopping the drug. The major properties of ticlopidine

and clopidogrel are compared in Table 39–2.

Ticlopidine is well absorbed (80–90%) from the GI tract.

It is rapidly metabolized with one active metabolite. Steady

state levels are achieved with 250 mg twice daily after 14 days.

The onset of antiplatelet effect is delayed (up to 2 weeks), so

ticlopidine should not be used when a rapid antiplatelet

effect is needed. Ticlopidine was introduced as a potential

alternative to aspirin, but its high cost, toxicity, and only

marginally better efficacy have limited its use in current

practice. Ticlopidine is approved for stroke prevention when

aspirin has failed or in patients who cannot tolerate aspirin.

Ticlopidine may cause neutropenia (2.4%), thrombocy-

topenia, or pancytopenia (0.04–0.08%), particularly in the

first 3 months of therapy, so monitoring of blood counts

must be done during that time. Thrombotic thrombocy-

topenic purpura (TTP) has been reported with ticlopidine

therapy (0.02–0.04%), but ticlopidine also has been used

successfully in management of TTP. Other adverse effects

include diarrhea (20%), skin rash (2–15%), increase in total

cholesterol levels (mean increase of 9%), and reversible liver

function test abnormalities (rare).

Clopidogrel is rapidly absorbed and metabolized to active

metabolites (the main one being SR 26334, a carboxylic acid

derivative). The onset of inhibition of platelet aggregation is

dose-dependent, occurring 2 hours after a single dose

(400 mg) but after 2–7 days with lower daily dosing (50–100

mg daily). Platelet function returns to normal 7 days after

stopping the drug, consistent with irreversible inhibition of

platelet function. A loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg

daily will result in a rapid and sustained antiplatelet effect; a

loading dose of 600 mg is used in patients undergoing percu-

taneous coronary intervention, but the optimal loading dose

has not been determined. Clopidogrel appears to have

CHAPTER 39

824

approximately the same antiplatelet effects as ticlopidine, but

because of its better safety profile, it has replaced ticlopidine

for most clinical situations. Its therapeutic efficacy appears to

be equivalent to aspirin in most settings except for sympto-

matic peripheral artery disease, in which it may be superior.

It is currently approved for use in patients with recent stroke

or myocardial infarction and in those who have peripheral

arterial vascular disease. Clopidogrel combined with aspirin

decreases the rate of cardiovascular events following acute

coronary syndromes compared with aspirin monotherapy

and is the standard regimen following placement of coronary

stents (for at least 1 month; longer duration may be better).

Combination therapy is associated with more bleeding than

with aspirin alone, but only with higher doses of aspirin

(>100 mg/day). The most common side effects of clopido-

grel are rash and diarrhea. GI bleeding occurs less often than

with aspirin (2%); however, in one study in patients who had

bleeding ulcers while taking aspirin, clopidogrel was associ-

ated with a higher rate of recurrent bleeding than aspirin

when each was combined with a proton-pump inhibitor.

Neutropenia has been reported less often than with ticlopi-

dine (0.8%), as has TTP (reported occurrence 1:250,000 per-

sons, about the same as the general population), usually

occurs within the first 2 weeks of treatment.

Integrin αIIbβ3 (Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa)

Receptor Inhibitors

Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) inhibitors block

the binding of fibrinogen to its receptor on the platelet

membrane, preventing platelet aggregation. There are three

GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors currently approved for use in the

United States: abciximab (recombinant humanized mono-

clonal antibody), eptifibatide (synthetic heptapeptide similar

to that found in snake venom from Sistrurus m barbouri), and

tirofiban (a nonpeptide mimetic), all of which are given intra-

venously. Prolongation of bleeding time and decreased

platelet aggregation in vitro are seen with all these agents, but

in contrast to aspirin, ticlopidine, and clopidogrel, these

effects are rapidly reversible after discontinuation of the drug.

Results of six large studies have shown that these agents, in

combination with aspirin and heparin, are effective for pre-

venting ischemic complications associated with percutaneous

coronary artery interventions. The benefits of these agents are

less certain for management of patients with acute coronary

syndromes who are not undergoing percutaneous interven-

tion; studies have yielded conflicting results in terms of bene-

fits, whereas in all studies there is a higher risk of bleeding

compared with standard therapy. Only diabetes have consis-

tently benefited from addition of one of these agents to stan-

dard therapy. Although coronary flow and reinfarction rates

are improved by adding GP IIb/IIIa blockade to throm-

bolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction, there does not

appear to be any mortality benefit for combined therapy, and

bleeding is increased by the combination. Four orally active

agents have been tested and are not more effective when

combined with aspirin or when given in place of aspirin for

patients with acute coronary syndromes and may increase

mortality. The observed increase in mortality may be due to

increased bleeding and a possible paradoxical prothrombotic

Ticlopidine Clopidogrel

Absorption (oral) 90% Rapid

Half-life 24–36 hours (single dose); 96 hours (after 14 days

or therapy)

Active metabolite SR 26334: 8 hours

Active metabolities Yes Requires metabolism to active inhibitor: SR 26334

Onset of antithrombotic action Delayed up to 2 weeks 2 hours (single 400 mg dose); 1 day (50–100 daily dose)

Recovery of platelet function after

discontinuing drug

7 days 7 days

Recommended dose 250 mg orally twice daily 300 mg loading dose; 75 mg orally daily

Clinical use Cerebral ischemia with aspirin failure or intolerance Peripheral vascular disease, prevention of recurrent

stroke, myocardial infarction. Combined with aspirin

after coronary artery stent placement.

Side effects Neutropenia (2.4%), thrombocytopenia, TTP

(0.2%–0.04%), aplastic anemia, rash, diarrhea

Rash, diarrhea, TTP (1/1,000,000), neutropenia

(0.8%), gastrointestinal bleeding (2%)

Expense About $2–3/pill About $3/pill

TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Table 39–2. Comparison of ticlopidine and clopidogrel.

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY

825

effect owing to activation of platelets. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors

can cause bleeding similar to that seen with fibrinolytic ther-

apy. They are contraindicated in patients with platelet counts

of less than 100,000/μL.

Abciximab binds rapidly to the platelet receptors, fol-

lowed by dose-dependent inhibition of platelet aggregation,

accompanied by prolongation of the bleeding time. Bleeding

time returns gradually to normal by 12 hours after a bolus

injection, and platelet aggregation normalizes within 48 hours.

A bolus dose of 0.25 mg/kg followed by a 10 μg/min contin-

uous infusion results in sustaining of the antiplatelet effect.

This regimen has been used to prevent ischemic events in

patients undergoing percutaneous transthoracic coronary

angioplasty (PTCA). Major bleeding, especially in combi-

nation with full-dose heparin, can occur with abciximab.

Reversible thrombocytopenia may occur (1–2%) as soon as

2 hours after starting therapy. Antibodies develop in about

6%. The antiplatelet effects of abciximab may be responsi-

ble for its therapeutic benefits, but it also inhibits throm-

bin formation, which may contribute to its antithrombotic

properties.

Eptifibatide may cause less bleeding time prolongation

than other GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors while causing equivalent

inhibition of platelet aggregation, although this effect may

have been related to methods of measurement. Like abcix-

imab, eptifibatide can inhibit thrombin generation. Several

dosing regimens have been used for eptifibatide, ranging

from a 90–180 μg/kg bolus followed by continuous infusion

rates between 0.5 and 2 μg/kg per minute for 18–24 hours.

Bleeding time returns to normal 1 hour after stopping the

infusion, whereas inhibition of platelet aggregation may last

4 hours or more. Eptifibatide does not appear to increase the

overall rate of thrombocytopenia, but it may cause severe

thrombocytopenia in a small number of patients.

Tirofiban is a nonpeptide inhibitor of the GP IIb/IIIa

receptor that increases bleeding time and inhibits platelet

aggregation. Its effects are augmented by simultaneous

administration of aspirin. Onset of platelet inhibition is

rapid (5 minutes) and returns to normal within 1.5–4 hours

after discontinuation. Reported studies use bolus doses of

5–15 μg/kg followed by infusions of 0.05–0.15 μg/kg per

minute. Severe reversible thrombocytopenia may complicate

treatment with tirofiban.

Dextran

Dextran (available in high- and low-molecular-weight formu-

lations) interferes with platelet function and fibrin polymer-

ization and enhances plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis. Although

dextran is a volume expander, hemodilution induced by dex-

tran does not appear to influence its antithrombotic effects.

Dextran is less effective than other agents for prevention of

VTE. Dextran has been used primarily during carotid

endarterectomy and microvascular procedures, but because

there are few data from controlled clinical trials, firm recom-

mendations about its role cannot be made. Dextran is not

effective in the treatment of active thromboembolic disease.

Because of its volume-expanding properties, dextran should

be avoided in patients at risk for volume overload. Dextran

occasionally may cause hypersensitivity reactions.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

Dipyridamole is the only phosphodiesterase inhibitor cur-

rently in use in the United States. Dipyridamole does not affect

platelet aggregation but prolongs platelet survival time in

patients with arterial thrombosis or prosthetic heart valves.

Dipyridamole does not appear to be a particularly effective

antithrombotic agent on its own, in part, owing to limited

bioavailability. A new preparation with improved bioavailabil-

ity combined with aspirin is available (200 mg dipyri-

damole/25 mg aspirin) and has demonstrated a significant

reduction in recurrent stroke or death in patients with prior

strokes or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). The most com-

mon side effect of dipyridamole is headache; it does not

appear to increase the risk of bleeding compared with placebo.

Anticoagulants

The commonly used anticoagulants interfere with blood clot

formation and extension by inhibiting coagulation factors

(eg, unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin) or

blocking the synthesis of biologically active coagulation fac-

tors (eg, vitamin K antagonists). These anticoagulants have

demonstrated efficacy in a wide range of thromboembolic

conditions, both venous and arterial. Indications for use of

anticoagulants are expanding. The development of several

new anticoagulants, including several direct thrombin

inhibitors (DTIs), with different mechanisms of action and

more favorable therapeutic indices has expanded the use of

anticoagulant therapy and increased the therapeutic options

for patients with complicated medical conditions.

Unfractionated Heparin (UFH)

UFH is derived from porcine intestine or bovine lung and is

a mixture of molecules of heterogeneous size (MW

3000–33,000). Heparin binds to antithrombin (AT; also

known as antithrombin III) and accelerates antithrombin’s

inhibition of activated thrombin and other coagulation fac-

tors (particularly activated factor X). Only about a third of

administered UFH contains the specific pentasaccharide

sequence that is necessary for binding to AT, and only those

molecules have anticoagulant activity. An additional

sequence of 13 saccharides is required for the AT-heparin

complex to bind with thrombin; however, only the pentasac-

charide sequence is required for inactivation of activated fac-

tor X. This heparin-AT interaction is the major mechanism

for heparin’s anticoagulant effect. At high concentrations,

heparin also can bind directly to heparin cofactor II and

inactivate thrombin. Heparin, particularly the high-

molecular-weight fractions, also inhibits platelet function. In

addition to its anticoagulant properties, heparin can increase

CHAPTER 39

826

vascular permeability, inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell

proliferation, and interfere with normal bone homeostasis.

Heparin is not well absorbed from the GI tract, so it must

be administered parenterally (subcutaneously or intra-

venously). Subcutaneous UFH has lower bioavailability and

should be accompanied by an intravenous bolus injection if

immediate anticoagulation is required and a higher initial

dose (about 10% greater than for IV administration).

The pharmacology of heparin is complex. It circulates

bound to plasma proteins, binds to endothelial cells, where it

is neutralized by platelet factor 4, and is taken up by

macrophages and desulfated. There is a nonlinear dose-

response relation and a dose-dependent biologic half-life.

The route of elimination of heparin is not certain; plasma

clearance is accelerated by the presence of acute thromboem-

bolism. The rate of clearance of heparin depends on the size

of the molecules; larger molecules are cleared more rapidly

than low-molecular-weight molecules.

Although there is a relationship between the dose of

UFH and its efficacy (as well as safety), the variability of

response to UFH requires monitoring and adjustment of

dose. Monitoring of UFH activity is based on its biologic

effect on in vitro coagulation. UFH prolongs three impor-

tant in vitro coagulation parameters: the thrombin time

(TT), the prothrombin time (PT), and the activated partial

thromboplastin time (aPTT). The TT is the most sensitive

indicator of heparin’s effect and may be used to detect even

small amounts of heparin. The TT is useful to differentiate

heparin’s effect from that of circulating inhibitors of coag-

ulation, which are phospholipid-dependent and therefore

will result in a prolonged aPTT but normal TT. The PT is

the least sensitive measure of heparin’s effect and is usu-

ally normal unless the patient is also receiving oral antico-

agulant treatment or is overanticoagulated. The aPTT is

intermediate in sensitivity and is the most commonly used

test for monitoring UFH. However, recent clinical studies

have found that the aPTT does not always reliably predict

response to therapy. In addition, commercial reagents

used in the aPTT assay have variable sensitivity to

heparin, which makes monitoring UFH therapy of uncer-

tain accuracy. Nevertheless, the aPTT is still the most

commonly used method for monitoring response to UFH.

In most clinical situations, the desired aPTT while receiv-

ing UFH is one and one-half to two times the control

time. Suggested adjustment of UFH dose based on aPTT

results is outlined in Table 39–3 and ideally should be

based on calibration of the aPTT reagent to correspond to

therapeutic heparin levels (0.3–0.7 IU/mL). Dose modifi-

cations should be made when UFH is used in combination

with thrombolytic therapy or platelet GP IIb/IIIa antago-

nists. When UFH is given subcutaneously, peak plasma

levels are reached after 3 hours.

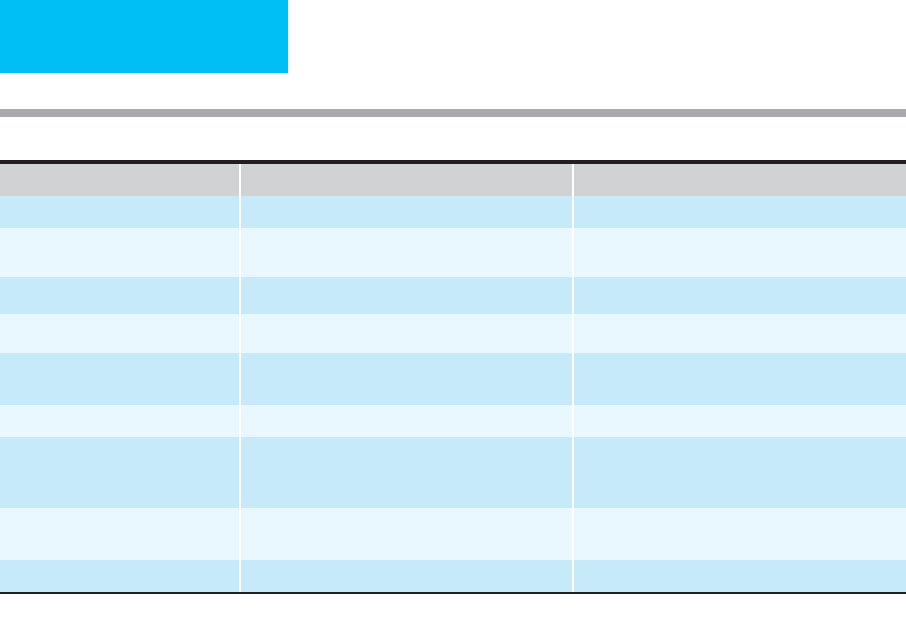

A. Initial Dose

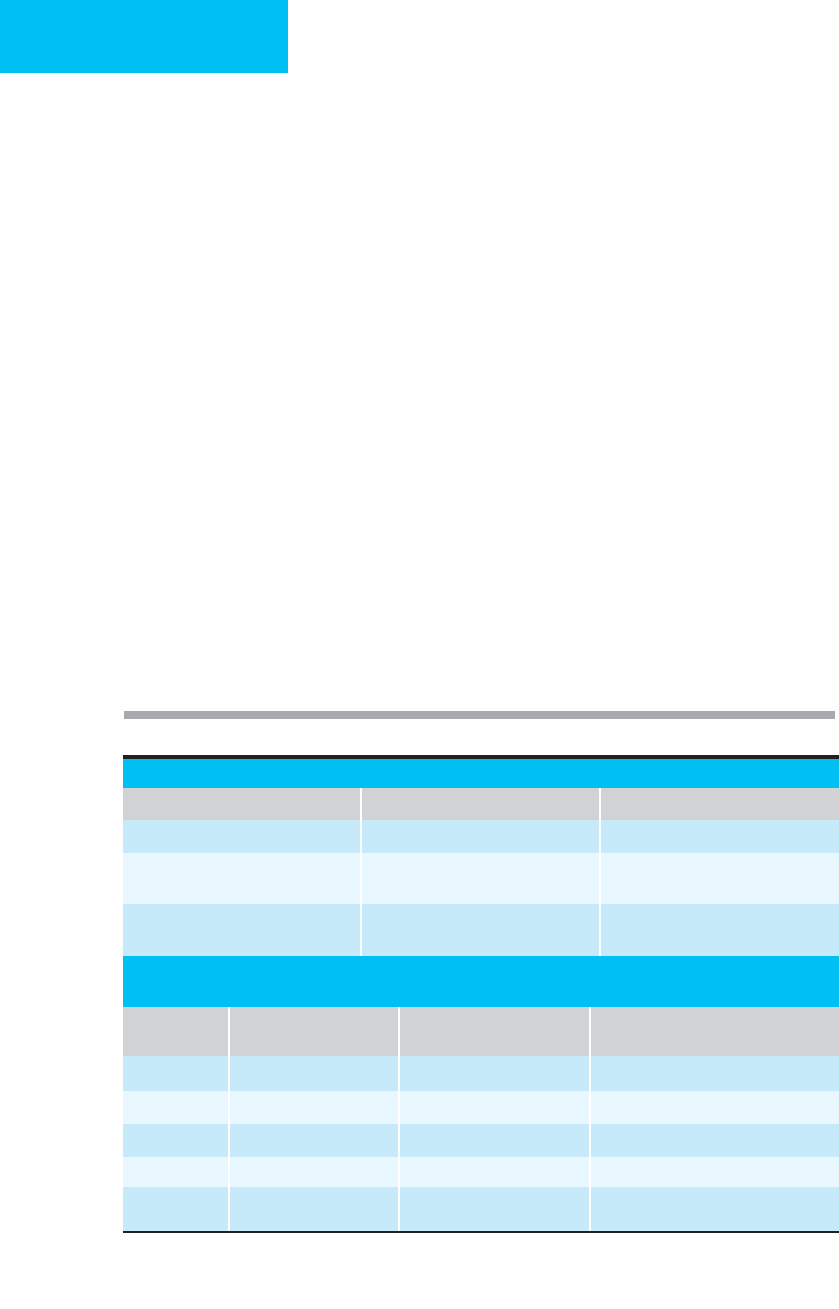

Indication Loading Dose by IV Bolus Initial Maintenance Infusion

∗

Venous thromboembolism 80 units/kg 18 units/kg/h

Unstable angina or acute myocardial

infarction

60–70 units/kg to maximum of

5000 units

12–15 units/kg/h (maximum

1000 units/h)

Concomitant alteplase for acute STEMI 60 units/kg to maximum of

4000 units

12 units/kg/h (maximum

1000 units/h)

Table 39–3. Unfractionated heparin, dosing and adjustment.

B. Subsequent Dose Adjustments Based on aPTT (First aPTT Obtained 6 hours after Starting

Unfractionated Heparin)

aPTT (s)

Rate Change

(units/kg/h)

Additional Action Obtain Next aPTT

<35 +4 Rebolus 80 units/kg 6 h

35–45 +2 Rebolus 40 units/kg 6 h

46–70

†

0 None Following morning

71–90 –2 None 6 h

>90 –3 Hold infusion 60 min 6 h

∗

Unfractionated heparin, 25,000 units in 250 mL D

5

W (100 units/mL).

†

The therapeutic range for aPTT should be standardize to correspond to therapeutic anti–factor Xa levels

(0.3–0.7 IU/mL).