Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

277

with 37% who did not develop nosocomial pneumonia.

Although this difference in mortality rate was not statistically

significant, VAP did increase the time spent in the ICU. The

diagnosis of VAP is very difficult. Presence or absence of

fever, leukocytosis, or purulent sputum are not sensitive

or specific for VAP. The combination of new infiltrates

plus two of fever, leukocytosis, or purulent sputum has a

likelihood ratio of 2.8. The absence of new infiltrates low-

ers the likelihood of VAP (likelihood ratio = 0.35). Some

investigators have recommended that patients undergo

invasive diagnostic testing using fiberoptic bronchoscopy

(eg, protected brush catheters with quantitative bacterial

cultures); others suggest that these data do not improve

diagnostic accuracy. Decreasing the frequency of ventila-

tor circuit changes is associated with fewer episodes of

nosocomial pneumonia. Attention to careful suctioning,

frequent draining of condensate in the ventilator circuit,

judicious use of antibiotics (including shorter courses),

and avoiding prolonged mechanical ventilation decrease

the risk of VAP.

Discontinuation of Mechanical Ventilation

(“Weaning”)

Mechanical ventilation can be discontinued easily and safely

in the majority of patients, that is, those who do not have

severe lung disease or neuromuscular weakness or who are

electively placed on mechanical ventilation for surgery. In

other patients—especially those with lung disease—mechanical

ventilation usually must be discontinued with careful moni-

toring using a variety of techniques. A gradual reduction in

ventilatory support has led to the use of the term weaning

from the mechanical ventilator as the patient resumes spon-

taneous ventilation, but there is growing evidence that many

patients in the ICU do not need slow withdrawal of

mechanical ventilation. Discontinuation of mechanical ven-

tilation should be distinguished from discontinuation of

endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy. Although the

terms intubation and ventilation are often used synony-

mously, there are some patients in whom intubation is

necessary but mechanical ventilation is not (eg, those with

upper airway obstruction).

In may ICUs, discontinuation of mechanical ventilation is

facilitated by protocols directing physicians, nurses, and res-

piratory therapists. These evidence-based protocols have

been successful in decreasing duration of mechanical venti-

lation and maximizing patient understanding and comfort

during the process. However, not all studies demonstrate that

such protocols are necessary.

A. Physiologic Assessment—For mechanical ventilation to

be discontinued, the patient must have a sustained ventila-

tory capacity that equals or exceeds the ventilatory require-

ment. For most patients who fail, the ventilatory requirement

(ie, how much minute ventilation is needed to maintain

Pa

CO

2

) is high relative to ventilatory capacity (how much

minute ventilation the patient is capable of providing

without assistance)(Table 12–11). The ventilatory require-

ment is a function of the metabolic rate (CO

2

production),

the set point for Pa

CO

2

, and the efficiency of lung gas

exchange (dead space:tidal volume ratio). Ventilatory capac-

ity is determined primarily by the interaction of ventilatory

drive, respiratory system mechanics, and inspiratory muscle

strength and endurance.

Disuse of respiratory muscles leads to atrophy, earlier and

easier fatigue, and possibly discoordination. In patients with

increased airway resistance or decreased lung or chest wall

compliance, respiratory muscles must generate relatively

greater pressure for a given tidal volume. Often these patients

have an increased ventilatory requirement and, therefore, an

increased pressure-time product—an index of muscle work

and potential for fatigue. Factors associated with decreased

muscle strength and endurance include electrolyte abnor-

malities (eg, hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia), critical

illness polymyopathy and polyneuropathy, high-dose corti-

costeroid therapy, malnutrition, and recent use of nondepo-

larizing muscle relaxants.

B. Predicting Successful Weaning—The underlying disease

that caused a need for mechanical ventilation must be cor-

rected first. The patient should have adequate gas exchange, as

evidenced by an only moderate supplemental oxygen require-

ment (Pa

O

2

/F

IO

2

>200), PEEP of less than 5–8 cm H

2

O, and

V

D

/V

T

of less than 0.50. The ventilatory requirement is gen-

erally the minute ventilation (

.

V

E

) provided during mechani-

cal ventilation. If gas exchange and the metabolic rate do

not change, the patient will have to provide this amount of

.

V

E

to maintain Pa

CO

2

at the preweaning level. Weaning is

usually unsuccessful when the

.

V

E

requirement is greater

than 10–12 L/min, or about twice the resting

.

V

E

in normal

adults. Adequate ventilatory capacity is encouraged by ensur-

ing normal plasma electrolytes (especially phosphorus,

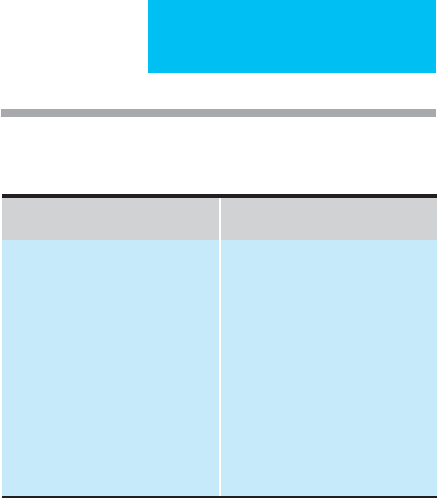

Increased Ventilatory

Requirement

Decreased Sustained

Ventilatory Capacity

Fever

Infection

Increased ventilatory drive

Metabolic acidosis

Excessive hyperalimentation

(especially with carbohydrate?)

Liver disease

Respiratory muscle fatigue

Hypokalemia

Hypophosphatemia

Decreased ventilatory drive

Bronchospasm

Airway secretions

Decreased lung or chest wall

compliance

Neuromuscular weakness

Malnutrition

Small endotracheal tube

Increased resistance of endotra-

cheal tube or ventilator circuit

Table 12–11. Factors contributing to difficult weaning:

Increased ventilatory requirement or decreased

ventilatory capacity.

CHAPTER 12

278

magnesium, and potassium), discontinuing sedatives, and

minimizing abnormal lung mechanics by treatment with

bronchodilators and suitable patient positioning.

Ventilatory capacity is assessed using a variety of weaning

parameters, some of which are shown in Table 12–12. Vital

capacity, negative inspiratory pressure, spontaneous

.

V

E

measured for 1 minute, and maximum voluntary ventilation

measured for 8–10 seconds estimate short-term ventilatory

capacity. These variables have excellent predictive value in

patients recovering from short-term general anesthesia, but

their predictive value is only marginal in patients with acute

or chronic lung diseases. This is largely because these param-

eters assess only ventilatory capacity and do not take into

account the ventilatory requirement and work of breathing.

In one study in which 58% of patients were weaned success-

fully, the following variables were found to be most closely

correlated with success:days of mechanical ventilation before

the weaning trial, respiratory frequency:tidal volume ratio,

maximal inspiratory pressure, maximal expiratory pressure,

and vital capacity. There were important differences between

groups with COPD, neurologic respiratory failure, and other

causes of respiratory failure; positive predictive values for

successful weaning ranged from 74–94%.

Indices that combine estimates of ventilatory require-

ment, work of breathing, and ventilatory capacity may be

useful. For example, a spontaneous respiratory rate:tidal vol-

ume ratio (f/V

T

) of less than 100/min/L may predict success-

ful weaning because it is an index of requirement and

capacity. This ratio, termed the rapid shallow breathing index,

proved to have greater sensitivity and specificity than other

variables for prediction of weaning. However, a report of

52 patients undergoing weaning from mechanical ventilation

indicated that 12 of 13 patients with a f/V

T

of more than

105/min/L were weaned successfully, whereas only one

patient who failed extubation had a ratio that high. One

interpretation is that very low f/V

T

ratios have a high positive

predictive value for successful weaning, whereas very high

ratios predict unsuccessful weaning well. On the other hand,

ratios of between 70 and 110/min/L are less useful.

Nevertheless, current predictors and clinical judgment of

successful weaning are poor. Because of this, a clinical trial of

patients who have marginal or low likelihoods of successful

weaning may be indicated. In an important study, all patients

using mechanical ventilation had a daily spontaneous

breathing trial unless contraindicated (eg, apnea, hypopnea,

severe hypoxemia, or high oxygen or minute ventilation

requirements). Surprisingly, a number of patients were dis-

continued successfully from mechanical ventilation who

would not have been predicted to do so by their clinicians. In

fact, patients who tolerate a spontaneous breathing trial of

30–120 minutes should be considered for immediate extuba-

tion in the absence of contraindications.

C. Weaning Methods—Patients who are easily weaned from

mechanical ventilation are easily weaned regardless of the

specific method used. Those who are difficult to wean for any

reason are difficult no matter which method is used. An

explanation of the weaning procedure, including descriptions

of possible discomfort and an assurance of close monitoring,

should be provided to the patient before weaning is started.

Once mechanical ventilatory support is being withdrawn,

slowly or rapidly, signs that should lead to restarting

mechanical ventilation or slowing the process include

tachypnea, tachycardia (HR >120 beats/min), hypotension,

severe anxiety, hypoxemia, respiratory acidosis (pH <7.30),

arrhythmias, chest pain, or other signs of hemodynamic

compromise. A study of a small number of patients showed

that a fall in gastric intramural pH, suggesting tissue

ischemia, was found in patients who failed weaning, whereas

those who were successful had no change in gastric intramu-

ral pH. In any patient who has difficulty being weaned from

mechanical ventilation, reassessment of ventilatory require-

ments and ventilatory capacity is indicated.

There are no conclusive studies demonstrating superior-

ity of any weaning method for patients with difficulty having

mechanical ventilation discontinued. Recent studies, how-

ever, suggest that spontaneous breathing trials followed by

extubation in suitable patients reduces length of ICU stay

and duration of mechanical ventilation. Although attractive,

noninvasive PPV in those with postextubated respiratory

distress has not been shown to benefit these patients.

Evidence that intermittent mandatory ventilation helps in

difficult patients is lacking.

1. T tube—The ventilator circuit is disconnected from the

endotracheal tube, and humidified oxygen is supplied by a

tube connected across the endotracheal tube connection

(T tube) while the patient breathes spontaneously. The

patient is observed carefully for signs of respiratory failure,

discomfort, severe dyspnea, or other intolerance.

If the T tube is used for a spontaneous breathing trial and

the patient tolerates the procedure for 30–120 minutes, then

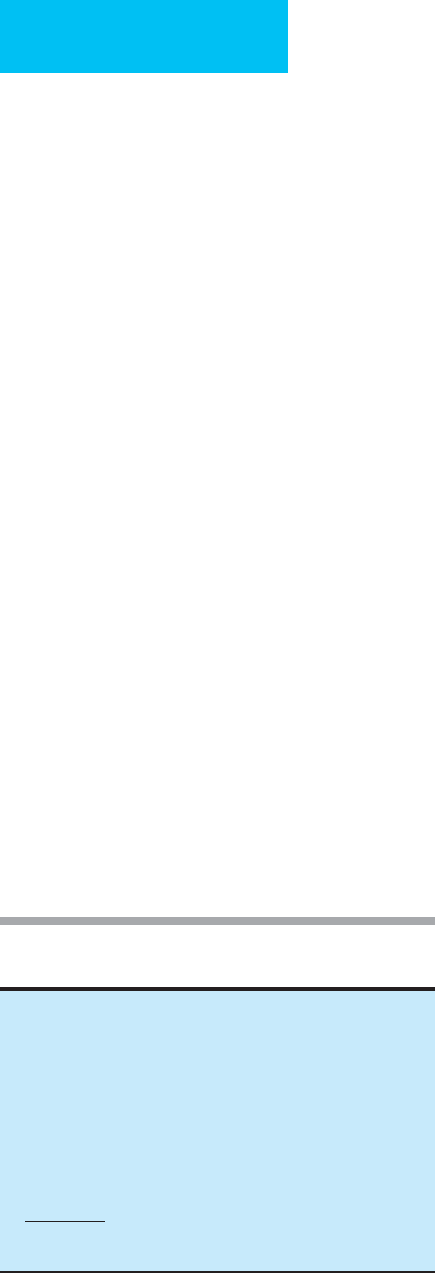

Table 12–12. Some variables used to predict success

during weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Ventilatory capacity

.

V

E

(on ventilator) <10 L/min and

.

V

E

(spontaneous) =

.

V

E

(on ventilator)

V

T

>5 mL/kg; VC >10–15 mL/kg

Spontaneous f <25/min

Maximum negative inspiratory pressure <–25 cm H

2

O

Maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV) >2 x

.

V

E

(ventilator)

Ventilatory requirement

Pa

O

2

>60 mm Hg with F

IO

2

<0.50

V

D

/V

T

<0.50

Combined indices

<100 breaths/min/L

Successful 30-minute spontaneous breathing trial

f breaths/min

V

T

(L)

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

279

the patient can be extubated. Otherwise, the duration of T-

tube sessions is increased depending on the patient’s

response. In between sessions, the patient is reconnected to

the mechanical ventilator in the assist-control mode. In some

patients, a T-tube session may be as short as 5–10 minutes at

first, with very gradual lengthening. The sessions may be

repeated two to four times daily depending on patient toler-

ance. It is important to strike a balance between excessive res-

piratory muscle fatigue during the sessions and adequate time

for the patient to assume some of the work of breathing.

A variation of the T-tube weaning method uses the venti-

lator circuit and ventilator to provide the air-oxygen mixture

during spontaneous breathing rather than a separate T tube.

This method allows for monitoring and warning of low

spontaneous tidal volume. However, some ventilator circuits

during spontaneous ventilation require much more patient

effort than the conventional T tube. Some mechanical venti-

lators provide gas mixtures to spontaneously breathing

patients with minimal work and effort by using continuous

flow or bypass circuits.

2. Intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV)—This

mode was described earlier. The number of mechanical ven-

tilator breaths each minute is decreased gradually over hours

or days while the patient provides a progressively increasing

share of the breaths taken each minute. The IMV mode in

some mechanical ventilators requires that the patient do

excessive work during the spontaneous breaths, and for this

reason, patients may tire easily. Despite encouraging data

when IMV was first used in the 1970s, there is no evidence

that IMV facilitates weaning in patients with lung disease or

in those who are difficult to wean. IMV has the advantage of

providing good monitoring of the patient during weaning,

with breath-by-breath spontaneous tidal volume and rate

displayed by most ventilators.

3. Pressure-support ventilation—The theoretic advan-

tages of PSV were outlined earlier. During weaning by this

technique, the pressure-support pressure is chosen initially

to achieve a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg and a respiratory rate

less than about 20 breaths/min. Pressure-support pressure

then is decreased gradually until the patient’s own tidal vol-

ume without pressure support is adequate. Mechanical ven-

tilation usually can be discontinued when the pressure

support is less than 7–10 cm H

2

O.

When it is desired to rest the inspiratory muscles tem-

porarily, either pressure-support pressure can be increased

until tidal volume reaches the desired level with little or no

patient effort or using conventional mechanical ventilation.

A few studies comparing PSV to T-tube weaning and IMV

have been completed, and T-tube weaning and PSV are sim-

ilarly more successful than IMV weaning. It is likely that PSV

and T-tube weaning will both be useful depending on patient

selection and clinician preference.

4. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation—

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation has potential benefits

in the weaning process after the patient is extubated. Some

studies have suggested that patients who are marginal wean-

ing candidates (eg, those with COPD with high ventilatory

requirements or low ventilatory capacity) may be extubated

successfully with the assistance of face-mask noninvasive

positive-pressure ventilation. The advantages might be

decreased duration of intubation, fewer complications, and

shorter hospital stays. Other studies have found that patients

who have failed weaning or extubation might be temporarily

supported using noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation

rather than reintubation. Recent studies have not shown par-

ticular benefit in selected and unselected patients. Further

studies are necessary to determine the precise role and out-

come of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in wean-

ing. If used, however, candidates should be selected carefully

and monitored closely.

5. Other methods—Facilities that specialize in manage-

ment and weaning of long-term ventilator-dependent

patients may be a less costly alternative than the ICU in

selected patients. A number of specialized centers have

reported considerable success in weaning patients after very

prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Anzueto A et al: Incidence, risk factors and outcome of baro-

trauma in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med

2004;30:612–9. [PMID: 14991090]

Boles JM et al: Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J

2007;29:1033–56. [PMID: 17470624]

Branson R: Understanding and implementing advances in ventila-

tor capabilities. Curr Opin Crit Care 2004;10:23–32. [PMID:

15166846]

Conti G et al: A prospective, blinded evaluation of indexes pro-

posed to predict weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Intensive Care Med 2004;30:830–6. [PMID: 15127195]

Esteban A et al: Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for

respiratory failure after extubation. N Engl J Med 2004;350:

2452–60. [PMID: 15190137]

Girou E et al: Association of noninvasive ventilation with nosoco-

mial infections and survival in critically ill patients. JAMA

2000;284:2361–7. [PMID: 11066187]

Haitsma JJ: Physiology of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Clin

2007;2:117–34. [PMID: 17368160]

Jonson B: Elastic pressure-volume curves in acute lung injury and

acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med

2005;31:205–12. [PMID: 15605228]

Kallet RH, Branson RD: Do the NIH ARDS Clinical Trials Network

PEEP/F

IO

2

tables provide the best evidence-based guide to bal-

ancing PEEP and F

IO

2

settings in adults? Respir Care

2007;52:461–75. [PMID: 17417980]

Klompas M: Does this patient have ventilator-associated pneumo-

nia? JAMA 2007;297:1583–93. [PMID: 17426278]

MacIntyre NR et al: Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and

discontinuing ventilatory support: A collective task force facili-

tated by the American College of Chest Physicians, the

American Association for Respiratory Care, and the American

College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 2001;120:375–95S.

[PMID: 11742959]

CHAPTER 12

280

Myers TR, MacIntyre NR: Does airway pressure release ventilation

offer important new advantages in mechanical ventilator sup-

port? Respir Care 2007;52:452–8. [PMID: 17417979]

Ni Chonghaile M, Higgins B, Laffey JG: Permissive hypercapnia:

Role in protective lung ventilatory strategies. Curr Opin Crit

Care 2005;11:56–62. [PMID: 15659946]

Peigang Y, Marini JJ: Ventilation of patients with asthma and

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Crit Care

2002;8:70-6. [PMID: 12205409]

Rothaar RC, Epstein SK: Extubation failure: Magnitude of the

problem, impact on outcomes, and prevention. Curr Opin Crit

Care 2003;9:59–66. [PMID: 12548031]

Vitacca M et al: Assessment of physiologic variables and subjective

comfort under different levels of pressure support ventilation.

Chest 2004;126:851–9. [PMID: 15364766]

ACUTE RESPIRATORY FAILURE FROM SPECIFIC

DISORDERS

Neuromuscular Disorders

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

May present with decreased ventilation owing to respi-

ratory muscle weakness (usually high respiratory rate

with low tidal volume) or decreased ventilatory drive

(low respiratory rate and tidal volume).

PaCo

2

>50 mm Hg.

VC <55% of predicted or less than 1500 mL may be

associated with hypercapnia.

Neuromuscular disorders often lead to atelectasis, aspi-

ration, pneumonia, hypoxemia, and poor cough reflex.

Suspect respiratory muscle weakness in all patients

with neuromuscular weakness; general muscle strength

does not always correlate with respiratory function.

General Considerations

Respiratory failure from neuromuscular diseases results from

respiratory muscle weakness or abnormal control of ventila-

tion. Muscle weakness or paralysis can result from disease in

any part of the nervous system involved with motor activity.

Problems with control of ventilation are seen in diseases that

affect the O

2

and CO

2

chemoreceptors, their connections to

the CNS, or the integrative and autonomic parts of the brain

stem, primarily the medulla.

In addition to respiratory failure, neuromuscular disease

can be associated with a number of other respiratory mani-

festations (Table 12–13). For critically ill patients, complica-

tions of nonneurologic diseases and treatment may include

neuromuscular weakness (eg, electrolyte abnormalities, cor-

ticosteroid myopathy, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neu-

ropathy) and depressed ventilatory drive (eg, sedatives and

opioid analgesics).

Pathophysiology

Respiratory failure in neuromuscular disease is due to weak-

ness of the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm. However,

other factors contribute to abnormal gas exchange

(Table 12–14). Acute weakness of inspiratory and expiratory

muscles results in a rapidly progressive decrease in vital

capacity and alveolar hypoventilation with hypoxemia. In

most cases, the mechanical properties of the chest wall are

altered, but the lungs are normal unless complications occur.

On the other hand, chronic neuromuscular disease may alter

the lungs and chest wall. Other factors that contribute to dif-

ferences in the presentation of respiratory failure include the

age of the patient at onset of disease, the distribution of mus-

cle weakness, a chronic or relapsing course, and the presence

of underlying lung or heart disease.

A. Normal Respiratory Muscles—Respiratory muscles

include the diaphragm, the intercostal muscles, muscles in the

neck that can generate additional respiratory effort, and mus-

cles of the abdominal wall. Other muscles play a key part in

ventilation, including muscles in the upper airway and the

smooth muscles of the lower airways. Respiratory muscles can

be divided into inspiratory and expiratory muscles, although

some are used during both parts of the respiratory cycle. The

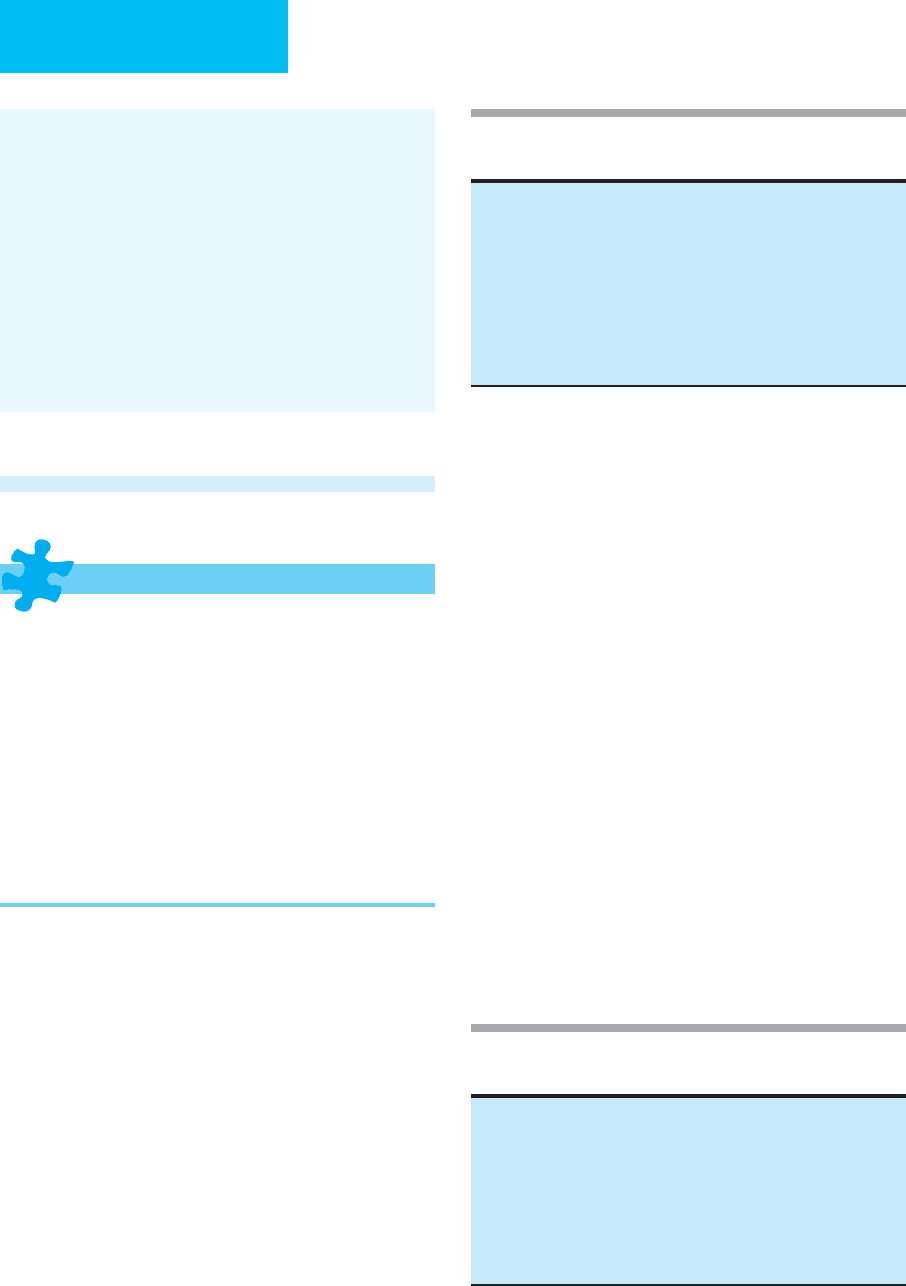

Table 12–13. Respiratory complications of neuromuscular

disease.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure

Hypoxemia

Pneumonia

Aspiration of gastric contents

Pulmonary edema

Abnormal ventilatory pattern

Upper airway obstruction

Atelectasis

Respiratory alkalosis

Pulmonary embolism

Table 12–14. Physiologic consequences of neuromuscu-

lar disease.

Decreased lung volumes

Alveolar hypoventilation

Decreased lung compliance

Increased chest wall compliance (acute weakness)

Decreased chest wall compliance (chronic spastic paralysis)

Abnormal abdominal wall mechanics

Ventilation-perfusion maldistribution

Atelectasis

Impaired cough effectiveness

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

281

diaphragm generates negative intrathoracic pressure during

contraction by pulling downward toward the abdomen.

However, if abdominal wall muscles contract simultaneously

with the diaphragm, the net effect is rather to pull the lower

margins of the rib cage upward and outward, thereby expand-

ing the thoracic volume. Muscles in the neck assist inspiratory

efforts, especially when the work of breathing is increased,

high ventilation is needed, the lungs are hyperinflated, or the

diaphragm becomes fatigued. These accessory muscles include

the sternocleidomastoids and scalenes.

Exhalation is usually passive, but normal subjects can

increase expiratory flow by contracting expiratory muscles

and generating higher positive intrathoracic pressures. Even

passive exhalation depends on respiratory muscles, however,

because passive expiratory flow is proportionate primarily to

airway caliber and lung elastic recoil; both these factors are

maximized at high lung volume, which requires good inspi-

ratory muscle strength to achieve.

B. Lung Volumes in Neuromuscular Disorders—Vital

capacity (VC) and inspiratory capacity (IC) are diminished

because of decreased ability to expand the lungs and chest wall

against passive inward recoil of those structures. While

decreased IC contributes to decreased total lung capacity

(TLC), the other component of TLC is the functional residual

capacity (FRC), often considered to be determined by the pas-

sive balance between inward recoil of the lung and outward

recoil of the chest wall at end expiration. But FRC does change

with the onset of neuromuscular weakness. For example, nor-

mal volunteers given submaximal doses of muscle relaxants

had about a 10% decrease in VC and TLC, but FRC decreased

about 20% as a result of decreased stiffness of the chest wall.

In patients with myasthenia gravis given pyridostigmine, an

increase in FRC correlating with an increase in respiratory

muscle strength was found. A study of stable patients with

moderate respiratory muscle weakness found that VC aver-

aged about 50% of predicted from height and age, TLC about

67% of predicted, and FRC about 79% of predicted.

In chronic neuromuscular disease, both altered chest wall

compliance and reduced lung compliance contribute further

to decreased FRC. Chest wall compliance in patients with

spinal cord injury and spastic paralysis of chest wall muscles

may be only 70% of normal. Small tidal volumes reduce lung

compliance, adversely affecting surfactant distribution and

perhaps stiffening and shortening lung fibrous and elastic

tissues from chronically reduced lung expansion.

C. Inadequate Cough—Inadequate cough, with retention of

secretions and increased tendency to pneumonia and atelec-

tasis, is the most common and important problem seen in

patients with neuromuscular weakness. Coughs are most

effective in removing secretions from airways if large shear

forces are generated by high-velocity gas movement in the

airways. In normal individuals, coughs are initiated at high

lung volumes, depend on vigorous contraction of expiratory

muscles to compress airways and generate high positive

intrathoracic pressures, and are released explosively. The

patient with neuromuscular weakness cannot produce effec-

tive cough if these three components are compromised.

The combination of low lung volume, impaired cough,

and accumulation of secretions leads to atelectasis. At low

lung volumes, alveoli are strongly influenced by surface forces

generated at the interface between the alveolar gas and the

wetted surface of the alveoli. This surface tension increases

the tendency of the alveoli to collapse. Airway secretions also

contribute to atelectasis by obstructing inward airflow and

allowing alveolar gas to be absorbed into the blood.

D. Abnormal Control of Ventilation—As described earlier,

alveolar ventilation in normal individuals is adjusted to regu-

late Pa

CO

2

. Hypoxemia also stimulates respiration but does not

play an active role in normal individuals at sea level. Neurologic

disorders that affect the central or peripheral chemoreceptors,

the integrative centers in the brain stem, or the primary outputs

to the respiratory muscles (phrenic nerves) may lead to inap-

propriate ventilation for the metabolic requirements of the

patient. Both hypoventilation and hyperventilation may be

seen depending on the site of the neurologic problem.

Clinical Features

Symptoms, signs, and laboratory findings depend on the

type of neuromuscular disorder leading to respiratory failure

(Table 12–15). Common to all forms of respiratory failure in

neuromuscular diseases are hypoxemia, hypercapnia, atelec-

tasis, poor cough, and risk of development of pneumonia

and other complications. Deep venous thrombosis and pul-

monary embolism are common in immobilized patients.

Occasionally, patients who have difficulty in weaning from

mechanical ventilation are found to have an unsuspected pri-

mary or secondary neuromuscular disorder.

A. Disorders of Ventilatory Control—Impaired ventilatory

control owing to a primary neurologic disorder is a relatively

unusual cause of respiratory failure. Patients present with low

respiratory rate and tidal volume, fluctuating uncoordinated

breathing patterns, or markedly periodic breathing. Diseases

that affect the medullary centers, including poliomyelitis and

cerebrovascular disease, as well as depression by CNS drugs or

hypothyroidism, can suppress the respiratory rhythm and out-

put from the autonomic nervous system. In patients with

impaired ventilatory control, clinical findings are related pri-

marily to the effects of respiratory failure on gas exchange in

addition to the consequences of the underlying disease. If CNS

depression from opioid or sedative drugs is present, patients

often will be lethargic or comatose. Other manifestations of

autonomic dysfunction such as hypertension or hypotension

and bradycardia or tachycardia can be seen in medullary

infarction. Furthermore, infarction or ischemia of the medulla

often results in characteristic effects on other neurologic path-

ways, including motor and sensory long tracts. A largely

reversible disorder of ventilatory control may be seen in

patients who have intermittent and transient hypoxemia, such

as seen in those with severe sleep-disordered breathing or

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

CHAPTER 12

282

B. Neuromuscular Weakness—Respiratory failure from

neuromuscular diseases that leave ventilatory control mech-

anisms intact usually presents with low tidal volume and,

because of the response to hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and lung

and chest wall mechanoreceptors, increased respiratory fre-

quency. There are some differences between the clinical pic-

tures depending on the particular disorder.

1. Muscle disease—Primary muscle diseases can be con-

genital or acquired. All can result in respiratory failure

when severe, including the congenital muscular dystro-

phies, inflammatory muscle disorders such as polymyositis

and dermatomyositis, drug-induced muscle weakness from

such agents as corticosteroids, and muscle weakness caused

by electrolyte and metabolic disturbances, including

hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypothyroidism, hyper-

thyroidism, and chronic renal failure. Muscle weakness may

not affect all muscle groups equally. Proximal muscles may

be more severely affected in some muscular dystrophies, and

even when respiratory failure is developing, there may be

poor correlation between the strength of the extremity mus-

cles and that of the respiratory muscles. Myotonic dystrophy,

a rare disorder presenting with weakness and myotonic phe-

nomena including impaired muscular relaxation, imposes

the additional burden of a stiff chest wall and increased work

of breathing.

The myopathic effects of corticosteroids can exacerbate

the effects of the underlying disease for which the drug is

administered, and corticosteroid-induced weakness in

patients with asthma or interstitial pneumonitis can con-

tribute substantially to respiratory impairment. A syndrome

associated with use of neuromuscular junction blocking

agents and corticosteroids can cause weakness and failure to

wean from mechanical ventilation. In some of these patients,

both evidence of myopathic changes on muscle biopsy and

neuropathic changes evidenced by nerve conduction studies

have been found. Hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia also

may precipitate respiratory failure in ICU patients.

Myxedema is associated with muscle weakness and elevated

plasma creatine kinase. Muscle weakness seen in thyroid dis-

ease is generally correlated with the severity of thyroid dis-

ease and corrects with treatment.

Patients with a variety of critical illnesses can develop a

syndrome called critical illness myopathy. This disorder has

been associated with critical illness polyneuropathy but may

occur alone. Clinically, these patients develop muscle weak-

ness during treatment for serious illness, although no specific

cause of muscle injury can be identified. Histopathologic

changes may include variation in muscle fiber size, fiber atro-

phy, angulated fibers, fatty degeneration, fibrosis, and single-

fiber necrosis, but there are no inflammatory changes. There

are structural differences between patients who receive corti-

costeroids and those whose muscles are affected by some

combination of cytokines and myotoxic substances.

Common predisposing conditions include ARDS, pneumo-

nia, liver and lung transplantation (possibly related to corti-

costeroids), liver failure, and acidosis. Because of common

predisposing conditions, critical illness polyneuropathy

should be distinguished from this syndrome. Both are asso-

ciated with difficulty in weaning from mechanical ventilation

and sometimes are not suspected until this stage of respira-

tory failure.

Primary muscle disorders often can be distinguished

from peripheral neuropathy by the absence of sensory find-

ings and by electromyography.

2. Peripheral neuropathies—Peripheral nervous system

disorders can be divided into those that affect the neuromus-

cular junction and those that affect the peripheral nerves.

Peripheral neuropathies, although seen in many disorders

such as vasculitis, diabetes mellitus, vitamin deficiencies,

Table 12–15. Neuromuscular diseases associated with

respiratory failure.

Medullary center injury or depression

Poliomyelitis

Cerebral vascular disease

Hypothyroidism

Narcotic and sedative drug overdosage

Primary muscle diseases

Muscular dystrophy

Myotonic dystrophy

Polymyositis, dermatomyositis

Drugs: corticosteroids

Hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia

Critical illness myopathy

Peripheral nerve diseases

Peripheral neuropathies

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Vasculitis

Diabetes

Vitamin deficiency

Toxin exposure

Infection

Infiltrative diseases

Critical illness polyneuropathy

Neuromuscular junction diseases

Myasthenia gravis and cholinergic crisis

Botulism

Tick paralysis

Drugs: paralyzing agents, aminoglycosides

Spinal cord injury and disease

Trauma

Poliomyelitis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Malignancy

Paraspinous or parameningeal abscess

Diaphragmatic paralysis

Cerebral cortical diseases

Stroke

Extrapyramidal disorders

Neurogenic pulmonary edema

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

283

toxin exposure (eg, lead), infections, and infiltrative diseases,

cause respiratory failure only rarely. For ICU patients, the

most important disorders are acute polyradiculoneuritis

(Guillain-Barré syndrome) and critical illness polyneuropa-

thy. Guillain-Barré syndrome is a demyelinating disease that

is seen most often several weeks after nonspecific viral or

other infectious illnesses, although the primary illness may

be asymptomatic or difficult to pinpoint. Some variants have

a strong association with prior Campylobacter jejuni infec-

tion. Clinical findings include ascending paralysis and sen-

sory involvement initially of the lower extremities. In

patients whose disease progresses over the course of about

2–4 weeks, involvement of the respiratory muscles, upper

extremities, and trunk may contribute to respiratory failure.

Autonomic instability may further complicate diagnosis and

management. Variants of Guillain-Barré syndrome may have

different patterns of involvement, making diagnosis more

difficult. About 5% of Guillain-Barré syndrome patients ini-

tially have ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and aflexia with less

striking extremity weakness (Miller-Fisher variant). Other

variants have purely motor or sensory involvement only.

Critical illness polyneuropathy is associated with sepsis

and multiple-organ failure. Manifestations include muscle

weakness and wasting and findings suggestive of peripheral

neuropathy. Patients have flaccid weakness and loss of deep

tendon reflexes. There is no evidence that metabolic or nutri-

tional factors or inflammation play a major role. The histo-

logic appearance of primary axonal degeneration and

denervation is consistent with widespread primary nerve

injury. It has been speculated that the association with failure

of other organ systems indicates that peripheral neuropathy is

another marker of severe systemic illness. Critical illness

polyneuropathy is associated with respiratory failure and dif-

ficulty in weaning from mechanical ventilation. As many as

70% of patients with sepsis and multiple-organ failure have

primary axonal degeneration of motor and sensory fibers,

and 30% have difficulty in weaning from mechanical ventila-

tion, limb muscle weakness, or diminished muscle reflexes.

Electrophysiologic studies show reduction or absence of mus-

cle and sensory action potentials, but slowing of nerve con-

duction or nerve conduction blocks is absent. Clinically,

patients with critical illness polyneuropathy should be evalu-

ated for botulism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, prolonged effects

of muscle relaxants, and critical illness myopathy. Some inves-

tigators do not make a distinction between critical illness

polyneuropathy and myopathy; the disorders are part of a

continuum of associated complications of critical illness.

3. Neuromuscular junction disorders—Neuromuscular

junction disorders include myasthenia gravis, an immuno-

logic disease caused by antibodies to acetylcholine receptors;

botulism, in which a specific neurotoxin produced by

Clostridium botulinum is ingested; and drug-induced disor-

ders, including pharmacologic blockade of the neuromus-

cular junction by paralyzing agents or inadvertent blockade

by aminoglycosides and other drugs. Myasthenia gravis

occasionally has gone unrecognized until it was severe

enough to present with respiratory failure. Botulism should

be suspected if there is descending paralysis and an appropri-

ate clinical history. On occasion, botulism results from toxin

produced by organisms infecting a wound, often in associa-

tion with parenteral drug abuse. Weakness or difficulty in

weaning in ICU patients should prompt a review of medica-

tions that can affect the neuromuscular junction. Rarely,

these include calcium channel blockers, quinidine, pro-

cainamide, and lithium.

4. Spinal cord disorders—Acute cervical spinal cord

injury resulting in quadriplegia may cause near-total respira-

tory muscle paralysis if above the C3 level, but some function

of neck muscles still may be present. If injury is below C3–4,

diaphragmatic activity may be preserved, but respiratory

failure may develop. In this setting, rib cage movement may

be paradoxical, with inspiratory effort causing the chest wall

to move inward because of flaccid paralysis of intercostal

muscles. The mechanical efficiency of the diaphragm is also

diminished as a result of flaccid paralysis of abdominal wall

muscles, and cough effectiveness is greatly reduced. With

time, the chest wall and abdominal wall become less compli-

ant as muscles become spastic. In some patients, these

changes may allow spontaneous efforts to become sufficient

to maintain ventilation.

Other spinal cord diseases presenting with respiratory

failure include poliomyelitis and amyotrophic lateral sclero-

sis. Poliomyelitis has a variable prognosis, with both weak-

ness and inability to protect the upper airway contributing

to potential respiratory failure. Amyotrophic lateral sclero-

sis is progressive, and respiratory failure is inevitable and

irreversible.

5. Diaphragmatic paralysis—Diaphragmatic paralysis

from bilateral phrenic nerve injury or disease is rare. Vital

capacity is usually less than 50% of predicted and worsens

when supine. The abdominal wall moves paradoxically

inward during inspiration, increasing the work of breathing

and making ventilation particularly inefficient for the other

muscles of inspiration. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is

often well tolerated unless there is underlying lung disease or

a requirement for increased work of breathing or minute

ventilation during illness.

C. Diseases of the Cerebral Cortex—Patients with strokes

have upper motor neuron paralysis but rarely present with

primary respiratory failure. However, respiratory problems

are the most common complications of stroke, including

aspiration and lung infection owing to generalized weakness,

immobility, and aspiration. More recently, the respiratory

complications of extrapyramidal disorders such as

Parkinson’s disease have become appreciated. The increased

stiffness of the chest wall increases the work of breathing,

and there are increased respiratory complications from

immobilization. Isolated closed head injury of any kind

requiring mechanical ventilation is commonly associated

CHAPTER 12

284

with pneumonia. In one study, 41% of these patients devel-

oped pneumonia and had a longer ICU stay compared with

those without pneumonia.

A rare complication of cerebral injury is neurogenic pul-

monary edema, seen in association with head injury, stroke,

status epilepticus, and cerebral hypoxia. Although it can be

indistinguishable from other forms of pulmonary edema,

neurogenic pulmonary edema may appear and disappear

rapidly despite causing severe gas-exchange disturbances.

The mechanism of neurogenic pulmonary edema is

unknown but may be related to extreme changes in pul-

monary vascular tone in response to autonomic stimuli.

Both increased lung epithelial permeability and increased

regional lung hydrostatic pressures cause pulmonary edema.

Among critically ill patients, abnormal neurologic status

is a major factor leading to prolonged mechanical ventila-

tion, with reduced level of consciousness the most common

cause. However, the underlying neurologic problem is more

likely a systemic illness (eg, drug toxicity or metabolic

encephalopathy) rather than a primary CNS disease.

D. Laboratory Findings—Hypoxemia is common, and a

Pa

O

2

of less than 70 mm Hg on room air is likely. Hypercapnia

with acute respiratory acidosis is the key marker of respira-

tory failure owing to neuromuscular weakness or decreased

ventilatory drive. Other laboratory findings are not particu-

larly useful, but abnormal plasma electrolytes, including

decreased potassium, magnesium, calcium, and phosphorus,

may contribute to muscle dysfunction. In patients with unex-

plained neuromuscular weakness, elevated plasma creatine

kinase suggests myopathy or myositis. Thyroid function tests

may be useful even if the patient lacks the usual signs of

hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Diagnosis of specific

neuromuscular disorders may be helped by electromyogra-

phy, nerve conduction studies, or nerve biopsy.

E. Imaging Studies—Complications of neuromuscular dis-

eases may be seen on chest x-ray. Atelectasis is a common

finding—either as macroatelectasis, with focal linear,

rounded, or other opacities visible on chest x-ray or evidence

of segmental, lobar, or other collapse, or in some cases with no

chest x-ray findings but only hypoxemia and an increased

P(

A

–a)

O

2

. In one study, 95% of patients with neuromuscular

disease requiring mechanical ventilation had atelectasis at some

time, most often as lobar atelectasis in the dependent lungs.

Aspiration pneumonia is another common respiratory compli-

cation of neuromuscular diseases. Although dependent areas of

the lungs are involved most often, new alveolar or interstitial

infiltrates anywhere in the lungs suggest pneumonia.

When assessing neurologic disorders associated with res-

piratory failure, CT scanning is not often useful in evaluating

the brain stem and has variable usefulness for spinal cord

abnormalities. MRI is highly effective for imaging these

areas, but patients cannot undergo MRI while being sup-

ported with mechanical ventilation.

F. Assessing Respiratory Muscle Strength—Prediction of

respiratory failure in these disorders involves assessment of

respiratory muscle strength. Adequate respiratory muscle

function requires both inspiratory and expiratory strength,

but neither maximum inspiratory pressure nor expiratory

pressure strongly correlates with general muscle strength. In

patients with polymyositis or other proximal muscle

myopathies presenting with generalized weakness, mean

maximum inspiratory and expiratory airway pressures aver-

aged about 50% of normal in one study, whereas at the same

time the average of maximum inspiratory and maximum

expiratory pressures were less than 70% of predicted in

about two-thirds of patients. Pa

CO

2

was inversely correlated

with both respiratory muscle strength and VC expressed as a

percentage of predicted. Hypercapnia was especially likely

when VC was less than 55% of predicted. In a study of

patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome, one-half of patients

developed respiratory failure. These had a mean VC when

intubation was required of about 15 mL/kg compared with

more than 40 mL/kg for nonintubated patients.

In patients with progressive neuromuscular weakness

who are at risk of respiratory failure, a reasonable approach

is to follow VC daily or more often if necessary. If VC falls

below about 20 mL/kg, is less than 55% of predicted, or

decreases below 1500 mL in an adult, respiratory failure

should be anticipated and arterial blood gases measured.

Intubation and mechanical ventilation (or noninvasive ven-

tilation if rapid reversal is expected) may be necessary if there

is progressive hypercapnia. Although some investigators rec-

ommend using the mean or sum of maximum inspiratory

and expiratory pressures rather than VC measurements, VC

is usually obtained more easily in the ICU.

Treatment

In most cases, treatment of respiratory failure owing to neu-

romuscular disease is supportive, including airway protec-

tion and mechanical ventilation. The exceptions are the few

diseases for which specific treatment is available, including

electrolyte abnormalities, myasthenia gravis, botulism, thy-

roid disease, and corticosteroid myopathy. It is essential to

prevent respiratory complications when possible and to rec-

ognize and treat them promptly when they occur.

A. General Care—Patients with neuromuscular disorders

should have attention to airway protection, including exami-

nation of the swallowing mechanism and gag reflex, alteration

of diet if necessary, careful feeding, and attention to body posi-

tioning. Feeding by mouth or by enteral feeding tubes should

be monitored closely, especially because some neuromuscular

diseases can affect gastric emptying and intestinal motility. In

all neuromuscular disorders—even when stable—respiratory

failure can be precipitated by stress from conditions such as

pulmonary or other infections, concurrent illness such as

heart failure, major surgery, medications, or electrolyte distur-

bances. General measures such as prophylaxis for gastritis and

prevention of deep venous thrombosis should be instituted.

Prevention of atelectasis by mechanical means is contro-

versial. Incentive spirometry is not as helpful in patients with

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

285

neuromuscular weakness as in those with normal strength.

Intermittent positive-pressure breathing (IPPB) seems

attractive as a way of overcoming low lung volume during

tidal breathing. However, results of studies have been mixed.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel

noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation also have been

tried without clear success. Some studies have shown that

rotational therapy using special beds is helpful in decreasing

atelectasis and pneumonia in immobile patients.

B. Treatment of Respiratory Failure—Treatment of respi-

ratory failure in patients with neuromuscular disease

includes airway maintenance, oxygen, bronchodilators if

necessary, and use of incentive spirometry to avoid atelecta-

sis. Respiratory failure is usually of the hypercapnic variety

unless there is atelectasis or consolidation from pneumonia.

Mechanical ventilation is often necessary to perform the

work of breathing in the patient with muscle weakness who

develops hypercapnia.

If respiratory drive is inadequate, the assist-control mode is

used with volume-preset ventilation. There is little rationale

for IMV or pressure-control ventilation, and pressure-support

ventilation cannot be used unless the patient can initiate and

sustain inspiratory efforts. Lung compliance and resistance are

normal in the absence of secondary pulmonary complications.

Unless and until ventilation-perfusion maldistribution devel-

ops, high concentrations of supplemental oxygen are not

needed. As in patients with obstructive or interstitial lung dis-

ease, tidal volumes should be limited to 6–8 mL/kg of ideal

body weight. PEEP may be quite helpful in decreasing atelec-

tasis and for reducing the sense of dyspnea in some patients.

Patients with specific neuromuscular diseases may pres-

ent with different needs. If respiratory muscle weakness is the

primary problem but ventilatory control is intact, pressure-

support ventilation may be suitable. In some disorders, it

may be desirable to rest the respiratory muscles entirely. The

assist mode does not “rest” inspiratory muscles as much as

the control mode—that is, if the patient initiates the breath,

the inspiratory muscles continue to contract throughout

inspiration, whereas if the ventilator initiates the breath,

inspiration is completely passive on the patient’s part.

Pressure-support ventilation, although the inspiratory mus-

cles are not completely rested, may have potential advantages

of allowing some work to be done but with less effort.

In some patients, positive-pressure ventilation is needed

only for some part of the day eg, (at night), and the patient can

breathe well for long periods of time. Tracheostomy may be

necessary to attach the ventilator at night, or noninvasive ven-

tilation may be tried for intermittent use.

Bednarik J, Lukas Z, Vondracek P: Critical illness polyneuromy-

opathy: the electrophysiological components of a complex

entity. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1505–14. [PMID: 12879242]

De Jonghe B et al: Critical illness neuromuscular syndromes. Crit

Care Clin 2007;23:55–69. [PMID: 17307116]

Laghi F, Tobin MJ: Disorders of the respiratory muscles. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:10–48. [PMID: 12826594]

MacDuff A, Grant IS: Critical care management of neuromuscular

disease, including long-term ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care

2003;9:106–12. [PMID: 12657972]

Mellies U, Dohna-Schwake C, Voit T: Respiratory function assess-

ment and intervention in neuromuscular disorders. Curr Opin

Neurol 2005;18:543–7. [PMID: 16155437]

Polkey MI, Moxham J: Clinical aspects of respiratory muscle dys-

function in the critically ill. Chest 2001;119:926–39. [PMID:

11243977]

Rabinstein AA, Wijdicks EF: Warning signs of imminent respira-

tory failure in neurological patients. Semin Neurol

2003;23:97–104. [PMID: 12870111]

Simonds AK: Recent advances in respiratory care for neuromuscu-

lar disease. Chest 2006;130:1879–86. [PMID: 17167012]

Thoracic Wall Disorders

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Chest wall anatomic deformity, chest wall stiffness, or

severe obesity.

Massive ascites, late-stage pregnancy, recent abdomi-

nal or thoracic surgery, thoracic and abdominal trauma,

and large abdominal or pelvic masses sometimes may

present with respiratory failure.

Paco

2

>50 mm Hg, usually with hypoxemia.

Low tidal volume; usually increased respiratory frequency.

Primary lung disease absent but secondary complications

frequent.

General Considerations

Thoracic wall abnormalities other than those owing to neu-

romuscular disease are relatively rare causes of respiratory

failure. However, acquired and congenital abnormalities may

result in distortion of the chest wall, mechanical disadvan-

tage of the respiratory muscles, increased work of breathing,

or limitation of chest wall expansion. Patients usually have

chronic respiratory failure with hypoxemia, hypercapnia,

and cor pulmonale but also may present with acute deterio-

ration or exacerbations. The most common chronic disor-

ders leading to respiratory failure are severe obesity of the

chest wall and abdomen, kyphoscoliosis and scoliosis, and

ankylosing spondylitis. Massive ascites, late-stage pregnancy,

recent abdominal or thoracic surgery and trauma, and

myotonic dystrophy may cause respiratory failure in a simi-

lar manner.

Pathophysiology

Thoracic cage abnormalities restrict lung expansion. Vital

capacity and total lung capacity are decreased. Functional

residual capacity (FRC) is usually decreased except in most

patients with spondylitis. Because of overall reduction in

lung volumes, FEV

1

is also usually low, but the ratio of FEV

1

CHAPTER 12

286

to VC is normal in the absence of obstructive lung disease.

Respiratory failure results from a combination of increased

work of breathing and ventilation-perfusion maldistribution

owing to restriction of expansion of the lungs and chest wall.

The mechanics of the chest wall and the diaphragm are

altered in ways unique to the type of disorder and the loca-

tion of the abnormalities.

A. Chest Wall Deformity—Scoliosis and kyphosis may be

idiopathic or due to poliomyelitis, tuberculosis, or other iden-

tifiable causes. Patients with scoliosis have an inverse relation-

ship between the severity of scoliotic deformity and the

compliance of the thoracic cage. Those who develop respira-

tory failure have the most severe thoracic deformity and low-

est chest wall compliance. Patients with scoliosis breathe at low

tidal volumes, presumably to minimize the work of breathing.

Kyphosis alone rarely is associated with respiratory failure, but

when seen together with scoliosis, it may contribute to

increased work of breathing and other abnormalities.

Ankylosing spondylitis limits rib cage expansion, and

patients tend to breathe primarily by diaphragmatic move-

ment as the thoracic cage becomes increasingly immobile.

The contribution of thoracic cage expansion to tidal breath-

ing falls as minute ventilation increases. The position of the

thoracic cage at end expiration often becomes fixed at a vol-

ume larger than in normal subjects. The chest wall therefore

exerts a greater than normal outward pull on the lungs, result-

ing in a normal or increased FRC despite low VC and TLC.

A flail chest results from severe blunt trauma outside the

hospital but occasionally from cardiopulmonary resuscita-

tion. The flail is the paradoxical inward movement of the

chest wall during inspiration, making ventilation inefficient

and worsening respiratory mechanics. Chest pain and

underlying lung contusions contribute to respiratory failure.

B. Obesity

1. Severe obesity—Severe obesity—in particular, predomi-

nantly central or truncal obesity—puts a heavy mechanical

burden on the chest wall and the diaphragm during inspira-

tion. Increased weight causes the end-expiratory position of

the chest wall and diaphragm to be more inward than nor-

mal. Thus the amount of gas that can be further expired from

the end-expiratory position (expiratory reserve volume

[ERV]) is reduced. On the other hand, the inspiratory

capacity—the maximal amount of gas that can be inspired

from the resting end-expiratory point—is normal or

increased, at least in young obese adults with no underlying

diseases. The work of breathing is increased, especially when

minute ventilation increases. The larger mass of the chest

wall and abdominal wall must be accelerated at each breath,

and additional energy is expended to move them during tidal

breathing. Small tidal volumes are usually selected by these

patients, and the ability to increase minute ventilation can be

limited and associated with severe dyspnea. It is likely that

obesity associated with more peripheral distribution of

added adipose tissue (eg, buttocks and extremities) has less

effect on respiratory function, but this has not been studied.

Obese patients are more prone to develop obstructive

sleep apnea because of a greater redundant soft tissue in the

upper airway, potentiating airway obstruction during sleep-

associated relaxation of upper airway muscles. A syndrome

of obesity-hypoventilation has been described. The mecha-

nism of this central hypoventilation is unclear but is proba-

bly associated with increased work of breathing, decreased

responsiveness of the respiratory center, and chronic hypox-

emia. These patients have daytime hypercapnia from

depressed chemoresponsiveness, increased work of breath-

ing, and abnormal pulmonary function. Patients with

obesity-hypertension syndrome often have pulmonary

hypertension and cor pulmonale.

C. Limitation of Diaphragmatic Excursion—Patients with

massive ascites, late stage of pregnancy, recent abdominal or

thoracic surgery or trauma, severe hepatomegaly, or large

pelvic or abdominal tumors may present occasionally with

respiratory problems. Most often they have basilar atelecta-

sis, low tidal volumes, and mild hypoxemia. If diaphragmatic

excursion is severely limited, these patients may develop

hypercapnia. The underlying condition may contribute to

additional problems. For example, patients with liver disease,

ascites, or tumors also may have pleural effusions, further

compromising lung function. Those with recent surgery or

trauma may be unable or unwilling to take deep inspirations

because of pain.

D. Gas Exchange and Pulmonary Hypertension—

Patients with all types of chest wall abnormalities may have

ventilation-perfusion maldistribution contributing to

hypoxemia and hypercapnia. In obesity and limited

diaphragmatic excursion, this finding has been attributed

primarily to atelectasis at the bases of the lungs because of

elevation of the diaphragm and low FRC. This is supported

by observations that obese subjects have better gas exchange

when standing than when supine and improvement in

hypoxemia and reduced P(

A

–a)

O

2

during exercise. Patients

with ascites and abdominal tumors would be expected to be

similar. In scoliosis and spondylitis, regional differences in

ventilation can be explained by differences in expansion

owing to local chest wall stiffness in spondylitis or asymmet-

ric deformity in scoliosis.

The combination of chronic hypoxemia and respiratory

acidosis along with anatomic deformity of pulmonary vessels

explains the pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale

seen in some patients with severe chest wall abnormalities.

For reasons that are not clear, cor pulmonale is seen more

often in chronic respiratory failure from scoliosis, sometimes

in the absence of severe gas-exchange abnormalities; it may

be related to anatomic deformity or arrested development of

pulmonary vessels.

Clinical Features

Some patients with thoracic wall abnormalities have chronic

respiratory failure with chronic hypoxemia and hypercapnia.