Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

307

dead space and achieve improved gas exchange with lower

tidal volume and pressure. As such, it may be an adjunct to

low-tidal-volume methods.

A more radical method of ventilation is partial liquid

ventilation (PLV), in which the lungs are filled with a per-

fluorocarbon, a substance in which oxygen is highly solu-

ble. Conventional volume-preset ventilation is used, but

gas movement through the lungs is almost entirely by dif-

fusion. PLV has the potential advantages of overcoming

loss of surfactant, recruiting lung units without increased

airway pressure, and avoiding further lung injury. Multiple

randomized trials of PLV have failed to show improved

outcome.

D. Supportive Care—Patients with ARDS often require pro-

longed mechanical ventilation and long duration of stay in

the ICU, putting them at risk for complications of ICU mon-

itoring and therapy, infection, and prolonged bed rest.

Attention must be paid to maintaining nutrition, preventing

deep venous thrombosis and GI bleeding, and preventing

other complications. However, recognizing that deaths in

patients with ARDS often result from infection and nonres-

piratory system failure, supportive care focuses especially on

minimizing cardiovascular compromise and preventing

infection.

E. Treatment and Prevention of Infection—Infection is

a major prognostic factor in ARDS, either as the primary

cause of ARDS or secondarily as a cause of death. In one

study, the mortality rate was 78% in patients who developed

ARDS during bacteremia and 60% in those who develop

nosocomial pneumonia. In another study, infection was

absent in two-thirds of survivors but present in two-thirds

of nonsurvivors. The major infection sites were the lungs or

pleura, the abdomen, soft tissues, and other locations, and

about 5% had multiple sites of infection. Gram-negative

bacilli made up 57% of 177 isolates causing infection in

ARDS in one series, whereas gram-positive cocci were found

in 36% and other organisms in 7%. Among pneumonias,

gram-negative organisms were found in 58% and were

related to endotracheal intubation and prolonged need for

ventilatory support. The finding of gram-negative pathogens

in ARDS patients with pneumonia assumes particular

importance because those patients had only a 12% survival

rate despite appropriate in vitro sensitivity of bacteria to

administered antibiotics, whereas patients with ARDS asso-

ciated with gram-negative bacillary abdominal infections

had a 59% survival rate.

Sepsis or severe pneumonia should be suspected as the

cause of ARDS in all patients unless a highly likely alternative

is present. A primary infection site may be easily identified,

but in doubtful cases, occult lung and abdominal sources

must be investigated. Antibiotics should be selected on the

basis of clinical findings and epidemiologic data. Some

important considerations include the likelihood of gram-

negative bacilli, staphylococci, and candidemia in hospitalized

patients; previous antibiotic use; the possibility of infection

with anaerobic organisms; immunologic competence of the

patient; gastric antacid administration; and other host and

local ICU factors. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is a com-

mon complication of ARDS with prolonged mechanical ven-

tilation. The diagnosis is difficult to confirm, but new or

changing infiltrates, fever, purulent sputum, and worsening

gas exchange are usually to make the diagnosis.

F. Pharmacologic Therapy—There are at present no estab-

lished pharmacologic therapies for ARDS. Many studies have

attempted to intervene in the early stages of ALI by interrup-

tion of cytokine pathways (eg, antagonists and receptor

antagonists), inhibition of endotoxin (eg, monoclonal anti-

bodies), reduction of nonspecific inflammation (eg, corti-

costeroids and prostaglandin and leukotriene inhibitors),

and prevention of oxidant damage (eg, antioxidants such as

acetylcysteine, vitamin C, and superoxide dismutase). None

has proved to be successful.

Nitric oxide is a potent endogenous vasodilator. When

given by inhalation in low concentration, it selectively dilates

pulmonary vessels in well-ventilated regions of the lung, and

it is rapidly inactivated before reaching the systemic circula-

tion. Clinical trials have shown improvement in gas exchange

probably because of improved distribution of pulmonary

perfusion. No large study has concluded that nitric oxide

improves clinical outcome.

Diuretics such as furosemide should be given to ARDS

patients who show evidence of volume overload and are judged

to have adequate systemic intravascular volume. Diuretics

should be used judiciously to avoid volume depletion and com-

promise of right and left ventricular filling. ARDS patients

often have increased airway resistance, so inhaled β-adrenergic

agonists may be helpful as bronchodilators. These drugs also

stimulate sodium and water transport by alveolar epithelial

cells, perhaps helping to resolve pulmonary edema.

Corticosteroids have been attractive in ARDS because of

potential roles for cytokine- and inflammation-mediated

lung injury, and these drugs are potent anti-inflammatory

agents. However, a large study found no difference in overall

mortality despite some improvement in gas exchange in

patients with ARDS for at least 7 days given large doses of

corticosteroids. The role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs, antioxidants, and other drugs such as ketoconazole

and pentoxifylline remains unclear despite small studies

showing potential benefit. Synthetic surfactants of different

types and components have been the subject of several stud-

ies in ARDS. In most, gas exchange improves, at least tran-

siently, but survival is not improved.

Prognosis

In the first description of the syndrome of ARDS, 12 patients

were described, of whom 7 died. Despite improvement in

care, the mortality rate has changed only slightly.

Nevertheless, recent studies have been encouraging. In one

CHAPTER 12

308

study from Seattle, mortality was 50–60% in the mid-1980s

but fell to 30–40% in the late 1990s. The large National

Institutes of Health (NIH)–sponsored trial using low tidal

volumes reported mortality of 30–40%.

A. Respiratory Failure and Outcome—Previously,

patients with ARDS often died early in the course of the dis-

ease from intractable hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Hypoxemia could not be corrected adequately by adminis-

tration of high concentrations of oxygen, and survival was

often less than 3 days after onset. Accordingly, treatment

focused on reversing hypoxemia with positive end-

expiratory pressure, changes in ventilator management, and

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Despite signifi-

cantly improved hypoxemia, these measures have had little

or no effect on outcome. One retrospective study found that

unmatched patients who did not receive PEEP had no

higher mortality than those who were given PEEP, although

the PEEP group died later in their course. Other studies

indicate that the severity of respiratory failure at the onset of

ARDS correlates poorly with mortality rate. In another

analysis, the number of neutrophils and lack of acidosis

were associated with survival, whereas the severity of respi-

ratory failure and lung mechanics, response to PEEP, wedge

pressure, blood pressure, and cardiac output were not pre-

dictive. On the other hand, a few studies do find a correla-

tion between outcome and severity of respiratory failure,

but more closely with initial response to therapy. That is,

those patients who have a marked improvement in oxygena-

tion with initial therapy (oxygen and PEEP) at 24 hours do

significantly better than those with a poorer response. More

recently, high dead space:tidal volume ratio has been shown

to correlate with poor outcome in ARDS.

B. Nonrespiratory Organ Failure and Outcome—In one

study, death associated with ARDS was due to irreversible

respiratory failure in only 16%, and most of these died in

the first 3 days. In contrast, of the deaths in this series, most

were due to sepsis, with others resulting from cardiac, CNS,

and hepatic failure. In another study, multiple-organ-

system dysfunction was found in almost all patients with

sepsis and ARDS but much less frequently in those with

ARDS who showed no evidence of infection. The kidneys

were the most commonly affected nonpulmonary organ in

ARDS, with renal failure developing and contributing to

morbidity and mortality data in 30–50%. In a European

multicenter report, the overall ARDS mortality rate was

59%, but death occurred in 38% of cases of ARDS follow-

ing trauma and 68% of those with intraabdominal sepsis.

Probably because of decreased organ-system reserve,

patients over age 70 in this report had a mortality rate of

82%. A study of the importance of multiple-organ-system

failure in ARDS found that nonsurvivors had more severe

thrombocytopenia than survivors, as well as lower blood

pH, more liver dysfunction, and higher plasma creatinine

concentrations.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

A. Fluid Management—Whether intravascular volume

should be reduced in ARDS remains a controversial issue.

Because of increased lung permeability, pulmonary edema is

maintained at pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressures

that are normal or low. It is argued that resolution of pul-

monary edema would be facilitated by lowering microvascu-

lar hydrostatic pressure with diuretics and fluid restriction.

On the other hand, there is concern about oxygen delivery to

the tissues in the face of intravascular volume depletion.

Positive-pressure ventilation and PEEP reduce cardiac out-

put and oxygen delivery, and cardiac output is maintained

by ensuring adequate intravascular fluid volume. Sepsis and

shock, major factors in ARDS, often require massive fluid

administration because of hypotension and decreased tissue

perfusion. These factors suggest that volume expansion may

be needed and that diuretics and negative fluid balance

should be avoided.

Retrospective evidence indicates that net negative fluid

balance is desirable in ARDS. Reduction of pulmonary

microvascular pressure decreases lung water despite severe

lung injury, and cumulative net negative fluid balance and

weight loss are significantly higher in survivors compared

with nonsurvivors of ARDS. These trials have the problem

of self-selecting patients with better prognoses, but they

nonetheless suggest that fluid balance may be an important

determinant of outcome. In one study, better survival in

ARDS was found in those who had at least a 25% reduction

in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure compared with those

who did not. Survivors of ARDS had lower wedge pressures

and body weights compared with nonsurvivors, and the mean

number of days of mechanical ventilation and days of ICU

care were less in those who gained less than 1 L of fluid over

the first 36 hours. There was no detrimental effect on nonpul-

monary organ system function despite low fluid intake.

Two prospective studies shed light on this problem. In

one, a more “conservative” strategy of fluid replacement was

compared with a more liberal one. Using central venous

pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP)

for guidance, as well as urine output and mean arterial pres-

sure, ALI patients were managed according to protocols.

Over the first 7 days, there was a very small negative cumula-

tive fluid balance for the conservative protocol; the liberal

protocol resulted in a mean positive fluid balance of nearly

7000 mL. There was no difference in 60-day mortality, but

the conservative strategy resulted in shorter duration of

mechanical ventilation and duration of ICU stay. There were

no additional complications.

In the other study, randomization of ALI patients to

insertion and use of a pulmonary artery catheter or central

venous catheter showed no difference in 60-day survival or

organ dysfunction. There were more arrhythmias seen with

the pulmonary artery catheter, but no differences in incidence

of renal failure or use of vasopressors, diuretics, or dialysis.

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

309

B. Periodic Lung Recruitment—The PV curve of the

lungs, both in normal individuals and in those with ARDS,

shows hysteresis, or a different curve during inflation and

deflation. Because the inflation limb requires higher pres-

sures at the same lung volume than the deflation limb, a

relatively high transpulmonary pressure may be needed

initially to “open” lung units. For subsequent breaths, the

pressure needed for inflation is considerably smaller. This

finding has led to the recommendation for periodic

“recruitment maneuvers” superimposed on conventional

ventilatory techniques.

One kind of recruitment maneuver consists of increasing

airway pressure to 30–45 cm H

2

O and holding pressure con-

stant for 30 seconds or more while ventilator cycling is inhib-

ited. This can be done by using the continuous positive

airway pressure (CPAP) mode, with the patient heavily

sedated or paralyzed. Successful recruitment is marked by a

subsequent increase in lung compliance (lower inspiratory

plateau pressure at the same tidal volume) and lower oxygen

requirements. The frequency, magnitude, safety, and clinical

benefit of aggressive lung recruitment are not established.

These maneuvers might be considered in patients with

refractory hypoxemia, but routine use is not supported by

current evidence.

C. Prone Positioning—A number of investigators have

advocated placing the ARDS patient into the prone position.

Several studies have demonstrated improvement in Pa

O

2

in

50–75% of patients turned from supine to prone, with some

patients having prolonged benefit. The mechanism of prone

positioning appears to be the smaller volume of lung that is

compressed by the abdominal contents and heart in the

prone position and by more uniform lung ventilation.

Hypoxemia is more likely to improve during early-stage

ARDS with pulmonary edema than after significant fibrosis

develops. Because the prone position may allow adequate gas

exchange with lower values of PEEP, tidal volume, and F

IO

2

,

this technique also might be considered a lung-protective

strategy.

Recent studies vary the daily duration of prone position-

ing, use changes in Pa

CO

2

to predict benefit, and compare

prone position with PEEP and recruitment maneuvers.

While there is general agreement that Pa

O

2

increases, current

evidence does not support a survival benefit.

D. Routine Use of PV Curves—PV curves have been recom-

mended for determining optimal PEEP and tidal volume lev-

els to avoid ventilator-associated lung injury. There is no

doubt that careful PV curve analysis has been instrumental in

enhancing our understanding of lung and chest wall mechan-

ics in ARDS, but routine use is not practical for a combina-

tion of technical and clinical reasons. Of interest, some

investigators have shown that current recommendations for

minimal PEEP, optimal tidal volume, and target plateau pres-

sure match very well with data derived from PV curves.

Adhikari N, Burns K, Meade M: Pharmacologic therapies for

adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syn-

drome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;4:CD004477. [PMID:

15495113]

Brower RG et al and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

ARDS Clinical Trials Network: Higher versus lower positive

end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory

distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2004;351:327–36. [PMID:

10793162]

Brower RG et al: Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pres-

sures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome.

N Engl J Med 2004;351:327–36. [PMID: 15269312]

Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, Esteban A: Epidemiology of acute

lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin

Respir Crit Care Med 2006;27:327–36. [PMID: 16909367]

Gattinoni L et al: Lung recruitment in patients with the acute res-

piratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1775–86.

[PMID: 16641394]

Gattinoni L et al: Lung recruitment in patients with the acute res-

piratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1775–86.

[PMID: 16641394]

Girard TD, Bernard GR: Mechanical ventilation in ARDS: A state-

of-the-art review. Chest 2007;131:921–9. [PMID: 17356115]

Lee-Chiong T Jr, Matthay RA: Drug-induced pulmonary edema

and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med

2004;25:95–104. [PMID: 15062601]

MacIntyre N: Ventilatory management of ALI/ARDS. Semin

Respir Crit Care Med 2006;27:396–403. [PMID: 16909373]

Marini JJ: Advances in the understanding of acute respiratory dis-

tress syndrome: Summarizing a decade of progress. Curr Opin

Crit Care 2004;10:265–71. [PMID: 15258498]

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory

Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network: Efficacy

and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory dis-

tress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1671–84.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory

Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network:

Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung

injury. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2564–75. [PMID: 16714767]

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory

Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network:

Pulmonary-artery versus central venous catheter to tuide treat-

ment of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2213–24.

[PMID: 16714768]

Nuckton TJ et al: Dead-space fraction as a risk factor for death in

the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med

2002;346:1281–6. [PMID: 11973365]

Silliman CC: The two-event model of transfusion-related acute

lung injury. Crit Care Med 2006;34:S124–31. [PMID: 16617256]

Steinberg KP, Kacmarek RM: Should tidal volume be 6 mL/kg

predicted body weight in virtually all patients with acute

respiratory failure? Respir Care 2007;52:556–67. [PMID:

17484788]

Terragni PP et al: Tidal hyperinflation during low tidal volume

ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med 2007;175:160–6. [PMID: 17038660]

Wheeler AP, Bernard GR: Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory

distress syndrome: A clinical review. Lancet 2007;369:1553–64.

[PMID: 17482987]

CHAPTER 12

310

Obstructive Sleep Apnea &

Obesity-Hypoventilation Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Excessive daytime somnolence with evidence of upper

airway obstruction during sleep (obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome).

Impaired ventilatory response to CO

2

and hypoxemia

(obesity-hypoventilation syndrome).

May have right-sided heart failure with cor pulmonale,

hypertension, and left ventricular dysfunction.

General Considerations

The obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome is a com-

mon condition affecting 5% of adult men and approximately

half that number of women. This syndrome is closely associ-

ated with snoring and is characterized by repeated episodes

of upper airway collapse during sleep with resulting acute

hypercapnia, hypoxemia, sleep disruption, hemodynamic

alterations, and impairment of daytime functioning. Severely

affected individuals may develop respiratory failure and be

admitted to the ICU with marked hypercapnia, poly-

cythemia, altered mental status, and pulmonary hyperten-

sion with cor pulmonale. Alternatively, obstructive sleep

apnea may be observed in ICU patients admitted for other

indications (eg, unstable angina pectoris or cardiogenic pul-

monary edema); in such cases, the recognition and treatment

of the sleep-disordered breathing may be a critical compo-

nent of the overall ICU therapy. It should be noted, however,

that most patients with obstructive sleep apnea do not have

daytime hypoventilation and therefore do not have respira-

tory failure in the usual sense.

A. Normal Breathing during Sleep—For the purpose of

this chapter, sleep may be separated into two main types,

rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non–rapid eye move-

ment (NREM) sleep, which differ considerably in their

effects on breathing and on upper airway resistance.

Although REM and NREM sleep stages alternate throughout

the night, the majority of REM sleep is normally concen-

trated during the latter half of the sleep period.

In normal awake individuals, the control of breathing is

influenced not only by chemical and mechanical stimuli but

also by inputs from higher cortical centers. With the transi-

tion to sleep (usually light NREM sleep), volitional influ-

ences are lost, and in addition, the responsiveness of the

central respiratory center to increasing Pa

CO

2

is blunted rel-

ative to the awake state. Upper airway caliber is also reduced

owing to both gravitational effects related to the supine posi-

tion and a decrease in the tonic activity of upper airway dila-

tor muscles, which, during wakefulness, prevent inspiratory

narrowing owing to negative intraairway pressures. The net

effects of these changes in ventilatory drive and airway cal-

iber are a slight increase in inspiratory upper airway resist-

ance and mild hypoventilation (Pa

CO

2

= 42–44 mm Hg at sea

level) relative to the awake state.

During REM sleep, respirations are irregular, and ventila-

tion appears to be, in part, under the control of behavioral

processes activated during this dreaming state. Ventilatory

responsiveness to chemical stimuli is markedly reduced, and

there is a profound suppression of skeletal muscle tone,

including the intercostal muscles and other accessory mus-

cles of respiration, but excluding the diaphragm and extraoc-

ular muscles. Although brief central apneas and hypopneas

can result in transient mild arterial oxygen desaturations,

these are clinically unimportant in normal individuals.

B. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome—In contrast to

mild narrowing of the upper airway found in normal persons,

an exaggerated response is seen in obstructive sleep apnea

syndrome, with episodic partial (hypopnea) or complete

(apnea) obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. These

events may last from 10–90 seconds and are terminated by an

arousal from sleep, resulting in sleep fragmentation. The site

of obstruction can occur at any point along the airway above

the level of the glottis, and often more than one site is

involved. A strong association of obstructive sleep apnea with

obesity in men suggests that small upper airway caliber is an

important predisposing factor, although obstructive sleep

apnea is found in nonobese individuals as well. Other poten-

tial factors include adenotonsillar hypertrophy or other

anatomic abnormalities, increased collapsibility of the upper

airway, inflammation or edema of these structures, and

abnormal neural reflexes. The degree of respiratory drive

plays a role, as does the amount of nasal airway resistance;

both these factors tend to increase the amount of intralumi-

nal negative pressure and, thereby, the tendency to collapse

the pharyngeal airway during inspiration.

Patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome tend to

experience most of their problems during the wake-to-sleep

transition (when ventilatory control is relatively unstable) and

during REM sleep (when respiratory muscle hypotonia and

chemical insensitivity combine to produce frequent and pro-

longed apneas). Because the threshold for arousal is relatively

low during lighter NREM sleep (stages 1 and 2), patients with

obstructive sleep apnea may alternate between these sleep

stages and wakefulness throughout the entire night and never

reach the more restorative deeper NREM stages 3 or 4. For

similar reasons, REM sleep is also typically fragmented and

reduced in quantity. While the severity of daytime sleepiness

generally correlates with the frequency of obstructive breath-

ing events, some patients may have minimal sleepiness despite

severe disruption of breathing during sleep (defined as more

than 30 apneas or hypopneas per hour).

Hemodynamic abnormalities during sleep are common

in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Hypoxemia and

high levels of circulating catecholamines contribute to both

increased systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance. Blood

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

311

pressure peaks immediately after an arousal occurs after an

obstructive event, when a sudden increase in cardiac output

meets these high vascular resistances. The markedly negative

intrathoracic pressures during obstructed inspiratory efforts

raise the transmural myocardial pressure, further increasing

both right and left ventricular afterload. In addition to

apnea-related fluctuations in blood pressure, obstructive

sleep apnea increases the risk of daytime hypertension. This

effect has been shown to be independent of obesity, age, and

gender and is thought to be related to a “resetting” of the

carotid baroreceptors as a result of repeated hypoxemia and

repetitive bursts of catecholamines with each obstructive

event that remodels vascular tone. Left ventricular hyper-

trophy is common in patients with obstructive sleep apnea,

and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (more often than

systolic abnormalities) may result in cardiogenic pul-

monary edema in these patients. Increased myocardial oxy-

gen requirements combined with apnea-related hypoxemia

can precipitate myocardial ischemia and present as noctur-

nal angina in patients with underlying coronary artery dis-

ease. Cardiac arrhythmias, including bradycardias and

pauses up to 13 seconds during apneas and ventricular

ectopy associated with severe desaturation, may be seen in

the most severe cases.

Obstructive sleep apnea also has been strongly associated

with coronary artery disease and stroke, although a direct

causal relationship has yet to be definitively demonstrated.

Suggested pathophysiologic mechanisms include the hemo-

dynamic abnormalities described earlier, as well as increases

in platelet activation and plasma fibrinogen that have been

reported in patients with untreated obstructive sleep apnea.

C. Obesity-Hypoventilation Syndrome—Obesity-

hypoventilation syndrome is an uncommon condition in

which usually morbidly obese individuals develop hypercapnic

respiratory failure from a combination of depressed response

to CO

2

and hypoxia, increased work of breathing, and possibly

abnormal heart and lung function. Obesity-hypoventilation

syndrome has a variable relationship to obstructive sleep apnea

perhaps because of the association of each with obesity, but

most obesity-hypoventilation syndrome patients have some

degree of obstructive sleep apnea. Obesity-hypoventilation

patients have daytime hypercapnia and decreased responsive-

ness to hypercapnia, in contrast to the majority of obstructive

sleep apnea patients, who, while awake, maintain normal Pa

CO

2

and have a normal ventilatory response to CO

2

. Patients with

obesity-hypoventilation syndrome often have pulmonary

hypertension leading to cor pulmonale.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with obstructive sleep

apnea may complain of daytime hypersomnolence, a history

of heavy snoring, awaking gasping for breath, and unrefresh-

ing sleep. Bed partners, if available, often provide more reli-

able information and will describe repeated periods of apnea

terminated by loud snorts and gasping. Systemic hypertension

is common. These patients may be seen occasionally in the

ICU for severe nocturnal hypoxemia, arrhythmias, cardiac

ischemia, heart failure, or altered mental status. Patients with

obesity-hypoventilation syndrome often have severe right-

and left-sided heart failure with dyspnea and pulmonary and

peripheral edema.

On examination of the obstructive sleep apnea patient,

periodic breathing may be noted during sleep. Unlike the

Cheyne-Stokes breathing pattern seen in severe heart failure,

however, the patient with obstructive sleep apnea will have

little or no airflow despite the increasing respiratory efforts.

After a time varying from seconds to minutes, the patient

arouses, may awaken briefly, and opens the airway to the

accompaniment of snoring and upper respiratory noises.

During the apnea, the patient may demonstrate use of acces-

sory muscles, intercostal retractions and paradoxical inspira-

tory chest wall movements, and movement of the neck

toward the thoracic inlet during inspiratory maneuvers.

These findings are characteristic of obstruction of the upper

airway while respiratory efforts are being made. Pulsus para-

doxus is not uncommon during apneic events.

Those with respiratory failure associated with obstructive

sleep apnea or those with obesity-hypoventilation syndrome

may have acute respiratory acidosis, which may be severe

enough to cause lethargy or coma. Other patients may seek

medical attention primarily for severe peripheral edema and

massive weight gain because of right ventricular failure from

pulmonary hypertension. Dyspnea or wheezing suggests a

component of obstructive lung disease or pulmonary edema.

Most, but not all, patients with severe sleep apnea will show

evidence of daytime hypersomnolence.

B. Laboratory Findings—Most patients with obstructive sleep

apnea have few abnormal laboratory findings when awake.

Erythrocytosis is unusual in obstructive sleep apnea alone and

suggests superimposed obesity-hypoventilation or other causes

of sustained hypoxemia. In patients seen in the ICU who pres-

ent with respiratory failure, hypercapnia and hypoxemia are

seen. Chronic CO

2

retention leads to a compensatory elevation

of plasma bicarbonate. Electrocardiography may show evi-

dence of left-sided or biventricular hypertrophy, tachycardia

or bradycardia in association with apneic events, and, rarely,

ventricular ectopy. The chest x-ray may confirm cardiomegaly,

pulmonary edema from left ventricular failure, or enlarged

pulmonary arteries in patients with pulmonary hypertension.

Patients with obesity-hypoventilation syndrome have abnor-

mally low ventilatory response to CO

2

and hypoxia.

C. Confirmatory Testing—Traditionally, confirmation of

obstructive sleep apnea has been made by polysomnography.

Measurements made during sleep demonstrate episodic

upper airway obstruction by showing periods of absence of

airflow despite evidence of inspiratory effort. Arterial

hypoxemia or O

2

desaturation proves that obstruction is

causing significant gas-exchange abnormalities. In the

sleep laboratory, the number, nature, severity, and duration of

sleep-disordered breathing events (ie, apneas and hypopneas)

CHAPTER 12

312

are carefully measured and counted. Other measurements

include electroencephalography and electrocardiography.

Portable cardiorespiratory recorders (four to six channels

including, at a minimum, airflow, respiratory effort, satura-

tion, and heart rate) are better suited for use in the ICU and

generally provide the information needed to guide treat-

ment. In some critically ill patients, diagnostic testing may

not be feasible, and a presumptive diagnosis of obstructive

sleep apnea may have to be made prior to confirmatory test-

ing. In these patients, direct observation of the sleeping

patient and pulse oximetry trends demonstrating an episodic

(sawtooth) pattern of desaturations in the ICU can be used

to initiate and titrate therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome may coexist with other lung

diseases. Both obstructive sleep apnea and COPD are common

in men, and these diseases complicate each other. Severe car-

diomyopathy and CNS disease may present with periodic

breathing, dyspnea, and hypersomnolence. Obesity is associ-

ated with hypoxemia from atelectasis. Weight gain, edema,

heart failure, and hypoventilation may be seen with hypothy-

roidism. Thyroid function should be determined in all patients

considered to have obesity-hypoventilation syndrome.

Treatment

A. Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea—Patients with mild

obstructive sleep apnea are unlikely to be seen in the ICU for

this problem alone, but this syndrome is common and may

be seen in those admitted with other diseases. In these

patients, apneic episodes occur relatively infrequently during

sleep onset and REM sleep, and daytime hypercapnia is not a

problem. Treatment is directed at weight reduction, absti-

nence from alcohol and cigarette use, treatment of nasal dis-

ease (if present), and avoidance of a supine body position

during sleep. Nocturnal nasal CPAP can be used if necessary.

Additional treatment options include mouthpieces that dis-

place the mandible anteriorly during sleep (thereby pulling

the tongue away from the posterior pharyngeal wall), and

rarely, pharyngeal surgery. Successful management should

result in reduced daytime somnolence and improvement of

such neuropsychiatric symptoms.

B. Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea—Severe obstructive

sleep apnea may require aggressive relief of nocturnal upper

airway obstruction. Tracheostomy is very effective because of

unequivocal reversal of upper airway obstruction, but this is

very rarely required.

1. Nasal CPAP—Nasal continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP) has become the treatment of choice for this disorder.

By providing positive pressure to the collapsible portion of

the upper airway during sleep, nasal CPAP effectively pre-

vents airway obstruction during inspiration.

Nasal CPAP is generally provided by a blower attached to

flexible tubing leading to a small mask placed over the nose or

small soft nasal prongs. A sufficient continuous flow of air is

blown into the system, and via a controllable vent, continuous

positive pressure of up to 20 cm H

2

O can be maintained. The

appropriate level of nasal CPAP is best determined during

polysomnography; however, rough approximations may be

made in the ICU by direct observation of the patient during

sleep, with upward titration of pressure until apneas, snoring,

and desaturations are eliminated. Newer “autotitrating”

devices that adjust pressure based on the shape of the inspira-

tory flow profile also can help to identify optimal pressures.

Most patients in whom it is tried, at least for the short term,

tolerate nasal CPAP, but not all patients can be managed suc-

cessfully in this way. For those unable to tolerate the required

continuous pressures, bilevel nasal ventilation may be more

comfortable and effective while allowing a high inspiratory

and a lower expiratory pressure level.

Nasal CPAP has a variable role in patients with obstructive

sleep apnea who present with respiratory failure to the ICU. In

many, nasal CPAP is sufficient to restore and maintain upper

airway patency and normalize gas exchange during sleep.

These patients probably have only mild respiratory center

depression from hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Some patients

are improved by the combination of nasal CPAP and oxygen.

On the other hand, some obstructive sleep apnea patients with

respiratory failure have little immediate response to nasal

CPAP, which suggests that upper airway obstruction is no

longer the only factor. In these patients, nasal CPAP can be

tried, but if satisfactory results are not obtained quickly, more

definitive efforts at restoring ventilation and oxygenation must

be made using mechanical ventilation.

Effective treatment with nasal CPAP is often accompa-

nied by a “rebound” of sleep, which gradually returns to

more normal quantities over several days. A spontaneous

diuresis is also seen commonly and is the result of a reduc-

tion in hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction and a

lowering of left ventricular afterload. Hypertension may

improve or even resolve with effective nasal CPAP therapy.

2. Oxygen—Oxygen, alone or given in combination with

noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, is given to correct

hypoxemia in the setting of respiratory failure with obstruc-

tive sleep apnea. Hypoxemia is a serious complication of this

syndrome, with potential for arrhythmias, altered mental

status, and further deterioration of ventilatory drive.

However, oxygen therapy alone typically prolongs apnea

duration, resulting in worsening hypercapnia and respiratory

acidosis.

In patients with acute respiratory failure, however, hypox-

emia is often very severe and may cause hypoxic inhibition of

central respiratory neural output and marked hypoxia of the

brain, heart, and other organs. The goal is to raise Pa

O

2

to at least

60 mm Hg for at least several days. Oxygen should be given with

careful monitoring of mental status, vital signs, respiratory rate,

and arterial blood gases. Increased hypercapnia indicating

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

313

worsening of respiratory failure with oxygen administration

should suggest the need for initiating or increasing ventilatory

support rather than discontinuing oxygen.

3. Other treatment—Endotracheal intubation or tra-

cheostomy is highly effective. In patients with localized

obstruction owing to adenotonsillar hypertrophy or nasal

polyps, surgical excision may be curative but should not be

done until the patient has been stabilized medically. Other

surgical treatments (including uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

and mandibular osteotomy with hyoid suspension) have

even less of a role in the actual setting because these proce-

dures tend only to reduce the severity of the obstruction, and

the results are difficult to predict. Diuretic administration

may be helpful if elimination of obstructive breathing events

and desaturations is insufficient to induce a spontaneous

diuresis. Pulmonary edema is often the result of left ventric-

ular diastolic dysfunction, and β-blockers may be more effec-

tive than afterload-reducing medications. There is no role for

respiratory stimulants or carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in

the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. The use

of sedative-hypnotic agents is contraindicated in these

patients because they suppress the arousal response and

therefore tend to lengthen apneas and cause more severe O

2

desaturations.

C. Obesity-Hypoventilation Syndrome—These patients

often benefit from diuresis in response to oxygen and diuret-

ics. Because of coexisting obstructive sleep apnea, mainte-

nance of upper airway patency is essential. Mechanical

ventilation may be necessary. Left ventricular failure is

treated with diuretics with β-blockers or afterload reduction

added as indicated clinically based on estimates or objective

measures of left ventricular function.

Mechanical ventilation should not be withheld until gas

exchange becomes severely abnormal. More often, mechani-

cal ventilation is required as a temporizing measure while

oxygen and other treatment correct the acute physiologic

derangement. Mechanical ventilation is sometimes necessary

so that oxygen can be given safely in patients who have

decreased ventilatory drive. After a few days of improved

Pa

O

2

, many patients will have improved ventilatory drive and

marked attenuation of hypercapnia. Patients often will

regain significant ventilatory responsiveness to CO

2

.

Some patients can be ventilated successfully using nonin-

vasive nasal ventilation with bilevel positive-pressure

ventilation. This procedure requires careful monitoring and

observation because minute ventilation and airway patency

cannot be guaranteed as with conventional mechanical ven-

tilation using an endotracheal tube. Bilevel positive-pressure

ventilation is much like inspiratory pressure-support ventila-

tion, with increased pressure maintained at a preset level

throughout inspiration. Although backup rates can be added

(similar to pressure-controlled IMV), they generally add lit-

tle to spontaneous ventilation in these patients owing to the

limited ability of inspiratory pressure applied noninvasively

to counteract forces produced by the weight of the chest and

abdomen.

Medroxyprogesterone acetate may have a beneficial effect

in patients with chronic obesity-hypoventilation syndrome,

but its usefulness in acute respiratory failure is unclear. In the

long term, weight loss is of substantial benefit because stud-

ies have shown that even a 10% reduction in weight can

improve gas-exchange derangements.

Arzt M et al: Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous

positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart

failure: A post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive

Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and

Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP). Circulation 2007;115:3173–80.

[PMID: 17562959]

BaHammam A, Syed S, Al-Mughairy A: Sleep-related breathing

disorders in obese patients presenting with acute respiratory

failure. Respir Med 2005;99:718–25. [PMID: 15878488]

Bradley TD et al: Continuous positive airway pressure for central

sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2025–33.

[PMID: 16282177]

Caples SM, Kara T, Somers VK: Cardiopulmonary consequences of

obstructive sleep apnea. Semin Respir Crit Care Med

2005;26:25–32. [PMID: 16052415]

Dincer HE, O’Neill W: Deleterious effects of sleep-disordered

breathing on the heart and vascular system. Respiration

2006;73:124–30. [PMID: 16293956]

Giles TL et al: Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive

sleep apnea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2006;3:CD001106. [PMID: 16855960]

Kushida CA et al: Practice parameters for the use of continuous

and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult

patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep

2006;29:375–80. [PMID: 16553024]

Yaggi HK et al: Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke

and death. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2034–41. [PMID:

16282178]

314

00

Acute Renal Failure

Acute renal failure can be defined as a precipitous impair-

ment of kidney function without regard to etiology or mech-

anism. It can occur as a result of many causes, but clinical

findings, complications, and some forms of treatment are the

same in all cases. The causes can be divided into three main

groups: prerenal, resulting from rapidly reversible renal

hypoperfusion; postrenal, owing to obstruction to urine flow;

and intrinsic, owing to lesions directly involving the renal

parenchyma. In most patients, intrinsic renal failure can be

considered a diagnosis of exclusion once pre- and postrenal

causes are eliminated.

Clinical Features

Investigations useful in determining the cause and severity of

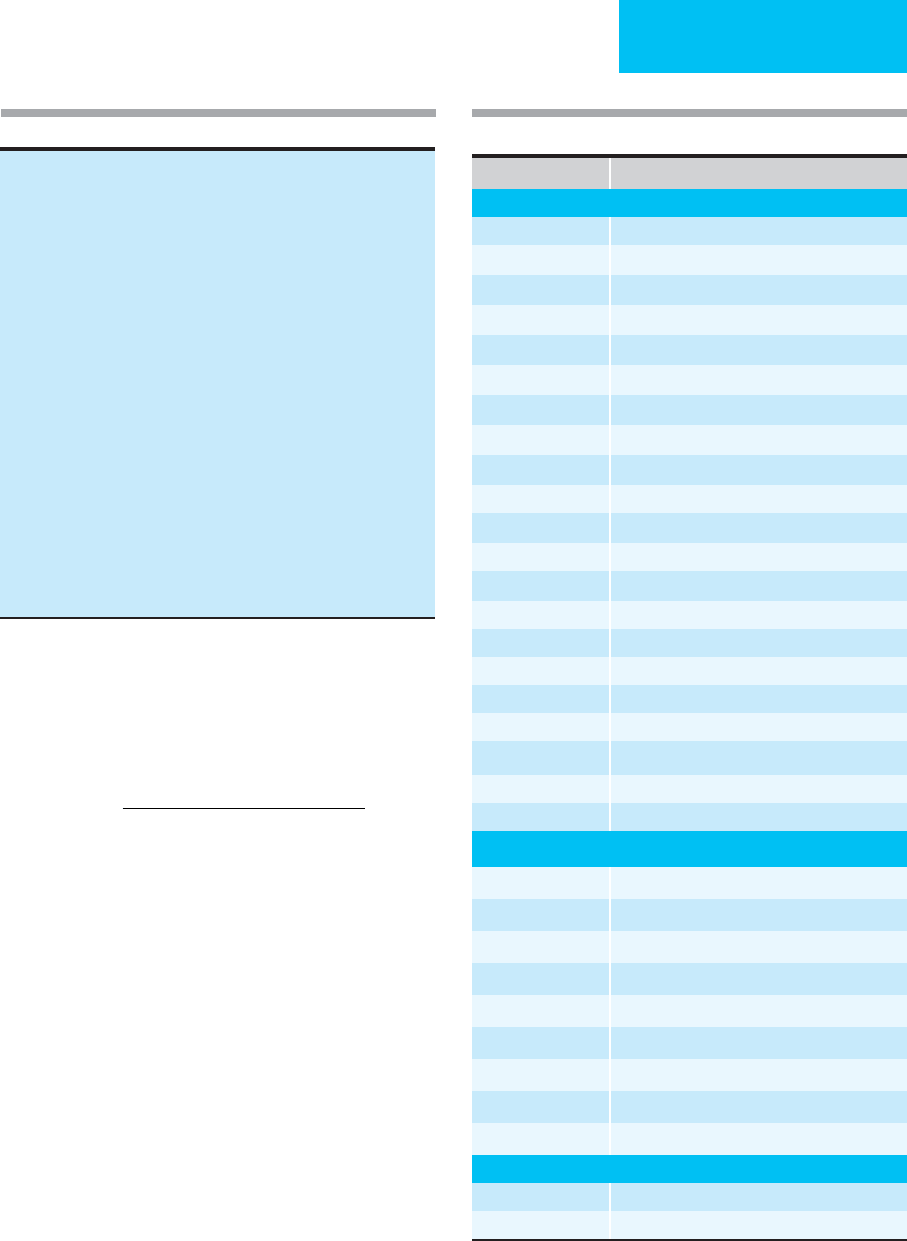

acute renal failure are listed in Table 13–1.

A. History—Noting the time of onset of renal problems

helps to differentiate between acute renal failure and the nat-

ural progression of chronic renal disease. The most com-

mon causes of chronic renal failure are diabetes,

hypertension, chronic glomerulonephritis, and polycystic

kidney disease. The patient’s drug history should seek to

identify medications known to cause renal dysfunction,

including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and

antibiotics (Table 13–2). Exposure to hydrocarbons (car-

bon tetrachloride), ethylene glycol (antifreeze), or radio-

logic contrast agents also can cause acute renal failure.

B. Symptoms and Signs—Acute renal failure is rarely asso-

ciated with flank pain or dysuria, exceptions being condi-

tions characterized by severe renal inflammation,

crystalluria, acute obstruction, intrarenal hemorrhage, and

arterial embolization. Most of the symptoms associated with

acute renal failure are the result of renal dysfunction. Salt and

water overload, resulting in edema, hypertension, and pul-

monary congestion, is most often the result of inadequate

diuresis. Manifestations associated with acute retention of

uremic toxins include anorexia, nausea, hiccupping, vomit-

ing, hematemesis, impaired hemostasis, neuromuscular irri-

tability, asterixis, lethargy, coma, and seizures. Conditions

seen more often after prolonged uremia include pruritus,

pericarditis, and anemia. Spontaneous bone fractures owing

to secondary hyperparathyroidism and altered vitamin D

metabolism are not associated with acute renal failure, and

their presence argues strongly for chronic uremia as the

cause. Hyperkalemia owing to impaired renal excretion can

cause cardiac arrhythmias. Uremic acidosis may elicit

Kussmaul respirations.

Evaluation of intravascular volume status and degree of

hydration should include measurement of orthostatic blood

pressure and heart rate, assessment of mucosal hydration

and skin turgor, and inspection for the presence or absence

of edema (peripheral and sacral), jugular venous distention,

pulsus paradoxus, cardiac rubs or gallops, pulmonary rales,

or effusions and ascites. Equally informative are signs of

associated morbidity, including those of congestive heart

failure, cirrhosis, or systemic vasculitis.

C. Laboratory Findings—

1. Serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate—

Creatinine is made in the muscle and released into the circu-

lation at a rate of 15–25 mg/kg per day for a middle-aged

man and 10–20 mg/kg per day for a middle-aged woman.

Under conditions of severe muscle damage (rhabdomyoly-

sis), leakage of creatinine into the serum can exceed the pre-

ceding estimates. Creatinine is excreted primarily by

glomerular filtration, with only a small percentage (10%)

secreted by the tubules and virtually none reabsorbed. The

normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR) must be reduced by

about half before there is a substantial increase in serum cre-

atinine levels (>1 mg/dL). As a result, serum creatinine is not

a reliable guide to modest decreases in renal function. In con-

trast, preexisting increases in serum creatinine support the

diagnosis of chronic renal disease.

13

Renal Failure

Andre A. Kaplan, MD

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

RENAL FAILURE

315

When creatinine levels are relatively stable over several

days, a crude estimate of the prevailing GFR can be made

using the following formula:

The result (in mL/min) is multiplied by 0.85 for a female.

This calculation is useful in providing a quick estimate of

renal function but is potentially misleading if there are sub-

sequent changes in the serum creatinine level. In order to val-

idate the calculation, a 24-hour urine collection for

creatinine is required.

During bouts of severe renal failure, serum creatinine

increases by 1–2 mg/dL per day. More rapid increases in

serum creatinine suggest rhabdomyolysis. Spurious increases

in serum creatinine can occur without declines in GFR when

certain cephalosporins or ketones (acetoacetate) interfere

with the colorimetric reaction used for its identification.

Likewise, cimetidine and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

can compete for tubular secretion and result in increases in

serum creatinine unrelated to decreased GFR.

2. Urea—Urea is the major nitrogen-containing metabolite

of protein catabolism and is excreted primarily by the kid-

neys. Normally, 35–50% of filtered urea is reabsorbed by the

tubules. Under conditions of decreased renal blood flow,

GFR

age][wt (kg)]

Serum creatinine (

=

−

×

[140

72

mmg/dL)

Table 13–1. Renal assessment.

History

Physical examination

Serum chemistries

Urea, creatinine, electrolytes, abnormal serologic tests (see text)

Urine chemistries

Na, FE

Na

, urea, FE

urea

, creatinine

24-hour clearance: creatinine, urea, protein

Urinalysis

Dipstick determinations

Microscopy

Sulfosalicylic acid

Urine culture/Gram stain

Hemodynamic monitoring

Ultrasound imaging

Radiography

KUB, IVP, tomography, CT scan, MRI

Invasive radiography

Renal arteriography (selective, digital subtraction)

Retrograde pyelography

Percutaneous antegrade pyelography

Nuclear scanning

Split function studies and renal flow (DTPA, MAG-3)

Gallium scan

Renal biopsy

Drug Mechanism of Nephrotoxicity

Antimicrobial Agents

Abacavir AIN

Acyclovir Crystalluria

Aminoglycosides ATN; electrolyte-wasting

Amphotericin B ATN; electrolyte-wasting, renal tubular acidosis

Cephalosporins AIN, spurious increased creatinine

Cidofovir ARF

Ciprofloxacin AIN

Dapsone ATN

Foscarnet ATN, electrolyte-wasting, hypocalcemia

Ganciclovir ARF

Indinavir Nephrolithiasis, crystalluria, pyuria, obstruction

Meropenem ARF

Penicillins AIN

Pentamidine ATN

Polymyxin B ATN (may occur when given orally)

Quinolones AIN?

Rifampin AIN

Sulfadiazine ARF, crystalluria

Sulfamethoxazole AIN, crystals, decreased creatinine secretion

Sulfisoxazole Crystalluria

Valacyclovir ARF

Immunosuppressive Agents

Cisplatin ATN, HUS, Glomerular capillary thrombosis

Cyclosporine Intrarenal vasoconstriction

Daclizumab ATN, renal dysfunction?

Ifosfamide ARF

Interferon Prerenal azotemia? ATN?

Interleukin-2 Shock-like syndrome, prerenal azotemia

Methotrexate Crystalluria (high-dose IV)

Mitomycin HUS

Tacrolimus Intrarenal vasoconstriction

Diuretics

All Prerenal azotemia

Mannitol Osmotic nephrosis

Table 13–2. Drugs associated with acute renal failure.

(

continued

)

CHAPTER 13

316

tubular reabsorption of urea can increase to 90% or more.

Since creatinine is not reabsorbed, serum urea increases

more rapidly than serum creatinine under these conditions,

as seen in prerenal renal failure. In general, when measured

as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in milligrams per deciliter, the

normal ratio of BUN to serum creatinine is 10:1. If it rises to

levels of 20:1 or more, one should suspect prerenal azotemia.

In addition to variations in renal handling, blood urea con-

centrations are also subject to the state of protein catabolism.

Thus 6 g of protein yields approximately 1 g of urea nitrogen.

Under most clinical conditions, there is a direct relationship

between the amount of protein ingested and urea nitrogen

production. Under conditions of stress, inadequate caloric

intake, or corticosteroid administration, endogenous protein

catabolism results in enhanced urea production. GI hemor-

rhage and the resulting absorption of blood proteins—

approximately 200 g of protein in 1 L of whole blood—also

can increase urea production.

3. Plasma electrolytes—Abnormalities of plasma

sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, calcium, magnesium, and

phosphate are common in acute renal failure, and their

determination and monitoring are an integral part of the

diagnosis and management of acute renal failure.

4. Serologic markers—A search for abnormal serologic

markers, such as various autoantibodies, is part of the basic

workup of immunologically mediated renal disease, includ-

ing glomerulonephritis.

5. Urine electrolytes—Evaluation of random urine sam-

ples provides quick information about the current state of

renal function. The fractional excretion of sodium (FE

Na

) is

the best means of differentiating between prerenal azotemia

and acute tubular necrosis and can be calculated as follows:

In the context of oliguria (urine output <500 mL/day), a

FE

Na

of less than 1% is most commonly associated with pre-

renal azotemia, but it also may be seen with acute glomeru-

lonephritis. Under similar oliguric conditions, a FE

Na

of

greater than 1% is probably related to acute tubular necrosis.

Unfortunately, the potential usefulness of this test is often

lost if diuretics are given prior to collection of the urine sam-

ple.

The fractional excretion of urea (FE

urea

) also can be use-

ful and is similarly calculated as follows:

Normal values in well-hydrated individuals are between

50% and 65%. Values below 35% are most compatible with

renal hypoperfusion and are not affected by loop diuretics

FE

urine Ur (mg/dL)

urine Cr (mg/dL)

ser

urea

=×

uum Cr (mg/dL)

serum Ur (mg/dL)

FE

urine Na (meq/L)

urine Cr (mg/dL)

serum

Na

=×

Cr (mg/dL)

serum Na (meq/L)

Drug Mechanism of Nephrotoxicity

Antihypertensives

ACE inhibitors Hemodynamic compromise (most common

with bilateral renal artery stenosis), AIN

Angiotensin receptor

blockers

Hemodynamic compromise (most common

with bilateral renal artery stenosis)

Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Celecoxib AIN

Diclofenac AIN

Fenoprofen AIN, nephrotic syndrome

Ibuprofen AIN

Indomethacin AIN, nephrotic syndrome

Ketorolac AIN

Nabumetone AIN

Naproxen AIN, nephrotic syndrome

NSAIDs (all) Prerenal azotemia (especially in CHF, cirrho-

sis, nephrosis, chronic renal failure, volume

depletion), ATN

Rofecoxib AIN

Sulindac AIN, nephrotic syndrome

Tolmetin AIN

Antiplatelet Agents

Clopidogrel HUS

Ticlopidine Nephrotic syndrome, HUS

MIscellaneous Agents

Allopurinol AIN

Cimetidine AIN, decreased creatinine secretion

Disopyramide Obstructive uropathy

Intravenous immune

globulin

Prerenal azotemia with filtration failure due

to hyperoncotic plasma

Lithium AIN

Omeprazole AIN

Phenindione AIN

Phenytoin AIN

Ranitidine AIN

Radiocontrast Agents

All ATN (especially with volume depletion or

advanced diabetic nephropathy)

Key: ACE = angiotension-converting enzyme, AIN = allergic intersti-

tial nephritis, ATN = acute tubular necrosis, CHF = congestive heart

failure, HUS = hemolytic uremic syndrome, NSAID = nonsteriodal

anti-inflammatory drug. (See Table 13–6.)

Table 13–2. Drugs associated with acute renal failure.

(continued)