Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ETHICAL, LEGAL, & PALLIATIVE/END-OF-LIFE CARE CONSIDERATIONS

217

Although rarely necessary, a legal decision can be sought

from the courts, such as in situations in which (1) the state

of the patient’s decision-making capacity is in doubt, or

(2) the surrogate decision maker cannot make or refuses to

make the decision, or (3) the health care team feels that the

surrogate’s decision is not in the patient’s best interests, or

(4) the surrogate’s decision is contrary to the patient’s

advance directive.

Shared Decision Making

Decision making in the ICU should be a shared responsibil-

ity between the physician and the patient or surrogate deci-

sion maker. The physician should avoid making

independent paternalistic medical decisions for the patient

involving life support measures even though doing so might

seem to be in the patient’s best interests. The physician is

singularly qualified to determine the medical futility of a

specific treatment, but only the patient or surrogate decision

maker can decide quality-of-life issues, that is, whether pro-

longation of life would be meaningful and valuable to the

patient. The physician should seek input from other mem-

bers of the patient’s health care team, including nurses and

other care providers.

Advance Care Planning

In an attempt to support the fundamental ethical principle of

patient autonomy, legislation has been enacted to facilitate

the process by which the patient’s wishes may be carried out

when he or she is no longer able to make decisions. That is, a

legal declaration by the patient gives the physician and health

care team advance notice of what he or she wants to be done

or not done under various future circumstances. Federal leg-

islation requires hospitals and skilled nursing facilities that

receive Medicare or Medicaid funding to inform all patients

of their right to complete such an advance directive. These

documents exist in most states, but the legal requirements

and implications vary in different jurisdictions.

The living will is the most common document by which

the patient may request or refuse life-sustaining treatment if

he or she becomes terminally ill and no longer able to make

medical decisions or becomes permanently unconscious.

Such documents are not legally binding in all states but

serve as guides for the physician and surrogate decision

maker. A legally binding natural advance death declaration

health care directive can include the decision to forego basic

life support measures of artificially administered nutrition

and hydration.

The advance health care directive appoints a health care

agent (“attorney-in-fact”) to act in the patient’s best interests

when the patient can no longer do so. Such an advance direc-

tive is most helpful when the patient has expressed his or her

wishes in writing in some detail rather than merely using

general terms such as “no heroic measures.” Ideally, individ-

uals executing these directives should discuss their intentions,

beliefs, and value systems with their health care agent, family,

and physician, in addition to completing the advance direc-

tive document. It is also important that these wishes and the

directive be reviewed on a regular basis, particularly each

time the patient is hospitalized.

Medicolegal Aspects of Decision Making

Critical care practices have been influenced by court actions

that were pursued to resolve ethical conflicts regarding

individual patients. While the actions are not legally bind-

ing outside those jurisdictions, they are used as legal prece-

dents to guide behavior and to aid in arriving at future

court decisions.

A number of cases have strengthened the ethical principle

of patient autonomy and have helped to clarify the role of the

surrogate decision maker in exercising the process of “substi-

tuted judgment” when acting for the patient. For example, in

1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court allowed the family of

Karen Quinlan to withdraw her from mechanical ventilation

because it agreed with her parents that this treatment would

not allow her to return to a cognitive and sapient life but

would merely keep her in a persistent vegetative state.

Similarly, legal decisions surrounding the care of Nancy

Cruzan in Missouri in 1990 ultimately acknowledged that

her parents as surrogate decision makers, based on past com-

ments the patient had made, could refuse life-sustaining

treatment, including nutrition and hydration.

Patient autonomy was further strengthened by the legal

determination in 1991 concerning the care of Helga Wanglie,

who was in a persistent vegetative state on a ventilator in

Minneapolis. The hospital had requested permission from

her husband to discontinue life support treatment based on

the medical decision that Ms Wanglie had no chance for

recovery, that is, that the treatment was futile. Her husband

refused, deciding that based on her religious beliefs,

Ms Wanglie would have wished to continue living. The court

affirmed Mr. Wanglie’s decision and refused to appoint an

independent conservator to replace him as decision maker.

More recently, the decision to withdraw nutrition and

hydration from Terri Schiavo, a woman in a persistent vege-

tative state following a cardiac arrest, was marked by pro-

tracted conflict between the patient’s husband and her

parents that went on for 15 years. The decision to withdraw

treatment was contested in the local, state, and federal judi-

cial systems, and even by Congress, before the treatment was

finally withdrawn, allowing the patient to die according to

her wishes shared in the past with her husband. This case

illustrates the value of advance care planning for everyone

and making one’s wishes in end-of-life care known to the

family rather than debating them later in the courts.

These precedents reaffirm the principle of patient auton-

omy, but ethical conflicts nonetheless remain, particularly

for individuals who stress the principle of justice and the fair

allocation of medical resources.

CHAPTER 10

218

Withholding & Withdrawing Life Support

Based on the ethical principles discussed in the preceding

paragraphs, the patient or the surrogate decision maker can

request that life support treatments be withheld or with-

drawn. Current judgment does not distinguish an ethical or

legal difference between the act of withholding and the act of

withdrawing life support measures. Nevertheless, the patient,

the family, and the health care team may find it more diffi-

cult to withdraw life support than to withhold it. In addition,

Orthodox Jewish tradition does not permit the withdrawing

of life support measures, including nutrition or hydration,

feeling that this would be equivalent to suicide. There is usu-

ally less concern about the more passive act of withholding

treatment.

Decisions to withhold or withdraw treatment are best

made in advance of a life-threatening situation, allowing the

patient and family to consider the potential outcome of life

support measures. This is particularly important in patients

who are terminally ill or who have an illness that is severe

and irreversible.

“Do Not (Attempt) Resuscitate (Resuscitation)”

(DNR/DNAR) Orders

In the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest in a hospitalized

patient, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is initiated

automatically. In some cases, it may be desired to forgo CPR,

in which case a “do not resuscitate” order is written. This

decision is made jointly by the patient (or surrogate) and the

physician, but either party may initiate discussion about the

decision. In general, physicians should initiate discussions

about CPR and DNR/DNAR—ideally, before the patient

becomes critically ill and before the disease progresses to a

life-threatening stage despite optimal therapy. Some writers

have advocated use of the term “allow natural death” (AND)

as more descriptive of the intent of this order.

The physician should choose an appropriate setting for

this discussion with the patient and family, allowing ample

time for discussion. The DNR/DNAR order should be pre-

sented in a positive light, emphasizing the continuation of

supportive treatment, relief of physical suffering such as pain

and dyspnea, and support for emotional suffering. It should

be made clear that such a decision does not mean that the

health care team is “giving up” but that the focus of therapy

is altered, emphasizing comfort while avoiding futile or

unnecessary treatment.

When the outcome is bleak, the discussion should focus

not only on whether CPR should be initiated but also on

whether life support measures should be withheld or with-

drawn. The “do not resuscitate” decision does not, by itself,

imply any decisions about other medical treatment, includ-

ing ICU admission, surgery, or other treatment. Thus, if the

patient’s outcome is likely to be poor, offering CPR may give

the patient and family false hope about the likelihood of a

good outcome. A better approach is to discuss whether to

withhold or withdraw life support measures when a crisis

develops if such measures are judged to be futile. The treat-

ment plan thus should be presented in an atmosphere that

will allow the patient, family, and health care team to “hope

for the best, but prepare for the worst.”

There may be situations in which a physician recom-

mends that a DNR order be written, but the patient or fam-

ily disagrees and wishes CPR to be initiated at the time of

cardiac or respiratory arrest. In this situation, several steps

can be taken. First, the physician and patient (or surrogate)

should continue the discussion, with clarification about the

reasons for each person’s decision, misconceptions about

CPR, and the continuation or discontinuation of other med-

ical care. Second, the American Medical Association (AMA)

Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs has decided that a

physician who determines that CPR may be futile may initi-

ate a DNR order against the patient’s wishes. In this situa-

tion, the patient must be informed of the decision and its

reasons. Third, in the event of disagreement, the patient

should be transferred to the care of another physician able to

reconcile the wishes of the patient with his or her own med-

ical judgment.

Once the decision for a DNR order is made by the patient

or physician, institutional policies and procedures should

govern how such an order should be written in order to avoid

miscommunication. Major points of the discussion with the

patient and family should be documented in the medical

record, including who participated, the decision-making

capacity of the patient, the medical diagnosis and prognosis,

and the reasons for the DNR decision.

Withholding or Withdrawing Treatment

A. A Stepwise Approach—Decisions to withhold or with-

draw life support treatment must not be made hastily.

Several steps are recommended: (1) The physician should

have a clear understanding of the patient’s diagnosis, physio-

logic and functional status, and any coexisting morbid states.

(2) The physician should seek unanimity among the health

care team for the decision to withhold or withdraw life sup-

port measures. (3) The next step is to seek informed consent

from a legally competent patient. If the patient is not legally

competent, the surrogate decision maker must be contacted.

It is wise to include the family and the patient’s referring or

primary care physician in the process, although the patient

or the surrogate decision maker holds responsibility for the

ultimate decision. (4) If a decision cannot be made in a

timely fashion and life support measures are imminently

required, the physician might consider recommending a lim-

ited trial of the life support measure—for example, ventila-

tory support for the next 72 hours, with reassessment at that

time. In the absence of a firm decision, life support measures

should be initiated or continued.

Physicians and other health care workers may fear that

their actions in withholding or withdrawing life support may

subject them to litigation or even criminal prosecution.

ETHICAL, LEGAL, & PALLIATIVE/END-OF-LIFE CARE CONSIDERATIONS

219

While no one is immune from criticism or challenge, health

care workers who act thoughtfully and rationally, with con-

cern for the patient and in the open company of their peers,

should not fear legal retribution.

B. Establish a Treatment Plan—Once a decision has been

made to withhold life support measures, a specific treatment

plan should be formulated with emphasis on providing com-

fort and support and continually adjusting the plan to meet

the changing needs of the patient. A DNR order should not

automatically preclude care for a patient in the ICU. All

efforts should be made to avoid giving the patient and fam-

ily a feeling of abandonment. Forgoing treatment does not

mean forgoing care. It may be helpful to involve the services

of a medical social worker or chaplain to make certain that

the patient and family receive appropriate emotional and

spiritual support and attention to their physical comfort.

C. Withdraw Life Support—When a decision to withdraw

life support measures has been made, the order should be

executed in a timely manner, paying close attention to the

emotional needs of the patient and family.

After the life support measure is discontinued—for

example, disconnecting the patient from mechanical

ventilation—the family should be allowed access to the

patient to the extent possible, and attention should be given

to their emotional and physical needs. If the dying process is

prolonged, the patient may be transferred to a separate room

for more privacy. Medications appropriate to control pain,

dyspnea, and other symptoms should be administered liber-

ally. Nursing care and physician attention should be as dili-

gent as before the decision was made. The primary training

and practice of critical care clinicians are to prevent and treat

life-threatening medical crises, but they also must be pre-

pared to provide palliative care, administering to the dying

patient and his or her family. A large body of educational

resources is available to assist the health care team in provid-

ing palliative care in the critical care setting.

Organ Donation

Organ transplantation has progressed rapidly in recent years

and now offers hope to patients who otherwise would die

because of failure of a vital organ. One of the limiting factors,

however, is the short supply of donor organs from individu-

als who have suffered irreversible cessation of brain stem

function.

In order to establish the diagnosis of death by neurologic

criteria, that is,“brain death,” a physician who has no conflict

of interest must verify by appropriate clinical evaluation that

the patient has suffered irreversible cessation of all brain

function. Such a diagnosis must be made in the absence of

hypothermia, drug effect, or metabolic intoxication that can

temporarily suppress the CNS. It also must be made with

caution in patients in shock because reduced brain perfusion

may make the examination unreliable. Guidelines have been

published by the American Academy of Neurology.

Because of the possibility that some patients may become

candidates for organ donation, physicians and health care

professionals in the ICU should be aware of the processes by

which donations can be made. Some patients already may

have disclosed in an advance directive that they wish to

donate body organs or tissues under these circumstances.

Otherwise, authorization for such organ donation must be

obtained from the surrogate decision maker or appropriate

family member unless the religious beliefs of the patient pre-

clude such donation (eg, Christian Science, Orthodox

Judaism, or Jehovah’s Witnesses).

Organ donation is a sensitive issue that health care

providers are often reluctant to raise, particularly at a time

when the potential donor patient’s family is suffering the

impending loss of their loved one. It is therefore necessary to

discuss these issues in a sensitive and timely manner once the

family has accepted the irreversibility of the brain damage.

Legislation in some states requires that such a discussion take

place. In the absence of any known family members or other

appropriate surrogate decision maker, the institution may be

permitted to arrange a donation in accordance with statutory

guidelines. It is important that all health care personnel be

familiar with the policies and procedures for organ donation

in order to identify potential transplant donors.

Role of the Health Care Professional

Education

All health care professionals who work in the critical care set-

ting should be intimately familiar with the ethical and legal

principles that influence their medical decision making. A

number of professional bodies have published position state-

ments on the ethical implications of critical care, and some

of these resources are listed in the references at the end of this

chapter and in the appendix of Web sites. Copies of these

statements should be readily available to critical care person-

nel. Skilled legal resources also should be available.

Discussions with patients concerning life support meas-

ures are potentially within the purview of all health care

workers, so this education should be offered to the entire

medical staff and all hospital medical personnel. The

patient’s primary physician ideally should initiate discussion

about advance directives and decisions concerning treatment

long before a crisis occurs. Such discussions can be encour-

aged through public education and by taking advantage of

opportunities to document decisions such as when preparing

wills and other estate planning instruments.

Communication Skills

In addition to possessing knowledge about the ethics of crit-

ical care medicine, health care workers should be skilled in

communicating these principles and their conflicts to

patients and families as well as among the health care team.

The physician traditionally assumes the role of the leader of

CHAPTER 10

220

that team, but critical care nurses and respiratory care prac-

titioners often develop close relationships with patients and

their families as well and can aid in the process.

Communication is aided by allowing ample time for dis-

cussing these issues in an appropriate setting—ideally, long

before a critical decision must be made. This would allow

general discussion of such sensitive issues as whether to ini-

tiate or withhold CPR or other life support measures and

other decisions about which the patient may wish to express

a preference.

Medical institutions should establish mechanisms by

which ethical conflicts can be resolved satisfactorily. This

might include the availability of ethics and/or palliative care

consultations, patient care conferences, and resources such as

patient advocates, medical social workers, and the hospital’s

retained legal advisers or others who are knowledgeable

about critical care and ethical issues.

Compassion Fatigue

Critical care professionals, by the nature of their work, are

subject to significant emotional distress in the care of criti-

cally ill and/or dying patients. This can result in compassion

fatigue, by which the emotional strain on the professional

caregivers begins to affect their decision making, care deliv-

ery, and sometimes their personal lives. Signs and symptoms

of compassion fatigue can include feelings of anger toward

the patient and family resulting in avoiding them and thus

stifling communication and empathy. This is best addressed

and/or avoided by providing an open and collegial atmos-

phere within the health care team, allowing members to dis-

cuss their feelings about caring for the patient and family.

Development of Institutional Policies

Institutional policies and procedures should be drafted to aid

the health care worker in responding to ethical issues in the

critical care arena and other areas of the hospital. A number

of such policies are listed in Table 10–2. They are designed as

much to prevent ethical conflicts as to aid in resolving them.

Guidelines for formulating these policies may be found in

the references listed below. Some state hospital associations

are also a resource for such policies.

REFERENCES

AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Medical futility in end-

of-life care. JAMA 1999;281:937–41. [PMID: 10078492]

AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: Ethical considerations in

the allocation of organs and other scarce medical resources among

patients. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:29–40. [PMID: 7802518]

Berger JT: Ethical challenges of partial do-not-resuscitate (DNR)

orders: Placing DNR orders in the context of a life-threatening

conditions care plan. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2270–75.

[PMID: 14581244]

Curtis JR et al: Missed opportunities during family conferences

about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 2005;171:844–9. [PMID: 15640361]

Meisel A, Snyder L, Quill T and the ACP-ASIM End-of-life Care

Consensus Panel: Seven legal barriers to end-of-life care. JAMA

2000;284:2495–2501. [PMID: 11074780]

Moreno R, Afonso S: Ethical, legal and organizational issues in the

ICU: Prediction of outcome. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006;12:

619–23. [PMID: 17077698]

Morrison RS, Meier D: Palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:

2582–90. [PMID: 15201415]

Perkins HS: Controlling death: The false promise of advance direc-

tives. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:51–7. [PMID: 17606961]

Rubenfeld GD: Principles and practice of withdrawing life-

sustaining treatments. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:435–51. [PMID:

15183212]

Schneiderman LJ et al: Effect of ethics consultations on nonbenefi-

cial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A ran-

domized, controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1166–72. [PMID:

12952998]

Snyder L, Leffler C, Ethics and Human Rights Committee, American

College of Physicians: Ethics Manual, 5th ed. Ann Intern Med

2005;142:560–82. [PMID: 15809467]

Szalados JE: Discontinuation of mechanical ventilation at end-of-

life: The ethical and legal boundaries of physician conduct in ter-

mination of life support. Crit Care Clin 2007;23:317–37, xi.

[PMID: 17368174]

Thompson BT et al, American Thoracic Society, European

Respiratory Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine,

Society of Critical Care Medicine, Societede Reanimation de

Langue Francaise: Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU:

Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in

Critical Care, Brussels, Belgium, April 2003, Executive summary.

Crit Care Med 2004;32:1781–4. [PMID: 15286559]

Tonelle MR: Waking the dying: Must we always attempt to involve

critically ill patients in end-of-life decisions? Chest

2005;127:637–42. [PMID: 15706007]

White DB et al: Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for criti-

cally ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and sur-

rogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2053–9. [PMID:

16763515]

Manno EM, Wijdicks EF: The declaration of death and the with-

drawal of care in the neurologic patient. Neurol Clin

2006;24:159–69. [PMID: 16443137]

Table 10–2. Institutional policies to help prevent or

resolve ethical conflicts in critical care.

Intensive care unit admission and discharge criteria

Methods for resolving ethical conflicts

Do not resuscitate orders

Guidelines for withholding and withdrawing life support

Care of the dying patient

Definition of and procedure for determining brain death

Requesting organ or tissue donation

Organizational ethics

ETHICAL, LEGAL, & PALLIATIVE/END-OF-LIFE CARE CONSIDERATIONS

221

APPENDIX 10A

Web Sites for Health Care Ethics

Information & Policies

These Web sites were operational as of April 7, 2008:

American Medical Association: www.ama-assn.org

The Hastings Center for Bioethics: www.thehastingscenter

.org

Medical College of Wisconsin Center for the Study of Ethics:

www.mcw.edu/bioethics

University of Pennsylvania Center for Bioethics, American

Journal of Bioethics Online: www.ajobonline.com

University of Pittsburgh Consortium Ethics Program:

www.pitt.edu/~cep

University of Toronto Joint Center for Bioethics: www.

utoronto.ca/jcb

University of Washington School of Medicine Ethics in

Medicine: http://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/toc.html

Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC): www.capc.org

Center for Ethics in Health Care: www.ohsu.edu/ethics

StopPain.org: www.stoppain.org

The EPEC Project: www.epec.net

End-of-Life Physician Education Resource Center:

www.eperc.mcw.edu

Five Wishes (advance care planning): www.agingwithdignity

.com

Southern California Cancer Pain Initiative: http://

sccpi.coh.org

222

00

The diagnosis and management of shock are among the

most common challenges the intensivist must deal with.

Shock may be broadly grouped into three pathophysiologic

categories: (1) hypovolemic, (2) distributive, and (3) car-

diac. Failure of end-organ cellular metabolism is a feature

of all three. Hemodynamic patterns vary greatly and consti-

tute the diagnostic features of the three types of shock.

HYPOVOLEMIC SHOCK

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Tachycardia and hypotension.

Cool and frequently cyanotic extremities.

Collapsed neck veins.

Oliguria or anuria.

Rapid correction of signs with volume infusion.

General Considerations

Hypovolemic shock occurs as a result of decreased circulat-

ing blood volume. The most common cause is trauma result-

ing in either external hemorrhage or concealed hemorrhage

from blunt or penetrating injury. Hypovolemic shock also

may occur as a result of sequestration of fluid within the

abdominal viscera or peritoneal cavity.

The severity of hypovolemic shock depends not only on

the volume deficit but also on the age and premorbid status

of the patient. The rate at which the volume was lost is a crit-

ical factor in the compensatory response. Volume loss over

extended periods, even in older, more severely compromised

patients, is better tolerated than rapid loss. Clinically, hypov-

olemic shock is classified as mild, moderate, or severe

depending on the blood volume lost (Table 11–1). While

these classifications are useful generalizations, the severity of

preexisting disease may create a critical situation in a patient

with only minimal hypovolemia.

Hypovolemic shock produces compensatory responses in

virtually all organ systems.

A. Cardiovascular Effects—The cardiovascular system

responds to volume loss through homeostatic mechanisms

for maintenance of cardiac output and blood pressure. The

two primary responses are increased heart rate and periph-

eral vasoconstriction, both mediated by the sympathetic

nervous system. The neuroendocrine response, which pro-

duces high levels of angiotensin and vasopressin, enhances

the sympathetic effects. Adrenergic discharge results in

constriction of large capacitance venules and small veins,

which reduces the capacitance of the venous circuit.

Because up to 60% of the circulating blood volume resides

in the venous reservoir, this action displaces blood toward

the heart to increase diastolic filling and stroke volume. It

is probable that venular constriction is the single most

important circulatory compensatory mechanism in hypo-

volemic shock.

Precapillary sphincter and arteriolar vasoconstriction

results in redirection of blood flow. The greatest decrease

occurs in the visceral and splanchnic circuits. Flow to bowel

and liver decreases early in experimental shock. Intestinal

perfusion is depressed out of proportion to reductions in

cardiac output. Reduction in flow to the kidneys accounts for

the decline in glomerular filtration and urine output,

whereas decreased skin flow is responsible for the cutaneous

coolness associated with hypovolemia. The cutaneous vaso-

constrictive response diverts flow to critical organs and has

the further effect of reducing heat loss through the skin. The

reduced diameter of the small, high-resistance vessels

increases the velocity of flow and decreases the viscosity of

blood as it reaches the ischemic vascular beds, thus permit-

ting more efficient microcirculatory flow.

Increased flow velocity in the microcirculation may

have the additional benefit of improving oxygen delivery

11

Shock & Resuscitation

Frederic S. Bongard, MD

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

SHOCK & RESUSCITATION

223

while reducing tissue acidosis. A countercurrent exchange

mechanism has been postulated in which oxygen diffuses

from arterioles into adjacent venules. Normally, the

amount of arterial oxygen lost by this mechanism is

small. However, as flow decreases through dilated arteri-

oles, more oxygen can leave the slowly flowing arterial

blood and diffuse to the venous circuit. Arteriolar con-

striction increases flow velocity and decreases blood resi-

dence time. This effectively reduces the peripheral oxygen

shunt. In a similar fashion, CO

2

diffuses from the post-

capillary venules into the arterioles. In the absence of

arteriolar vasoconstriction, such diffusion could increase

the volume of CO

2

reaching the tissues and result in

worsening of tissue acidosis.

The balance of fluid shifts between the intravascular and

extravascular spaces is governed by Starling’s law, which

relates net transvascular flux to differences in hydrostatic and

osmotic pressure:

.

Q = K[(P

c

− P

i

) − σ(Π

c

−Π

i

)]

where Q is fluid flux, (P

c

– P

i

) is the hydrostatic pressure gra-

dient, (Π

c

– Π

i

) is the osmotic pressure gradient, K is the per-

meability coefficient, and σ is the reflection coefficient.

Under normal circumstances, intravascular hydrostatic

pressure (P

c

) is greater than interstitial hydrostatic pres-

sure (P

i

), and fluid tends to move from the capillaries into

the interstitium. Interstitial osmotic pressure (Π

i

) is usu-

ally less than the intravascular osmotic pressure (Π

c

),

favoring the movement of fluid back into the capillary.

This results in a small net movement of water, Na

+

, and K

+

out of the capillaries. When hypovolemia occurs, intravas-

cular pressure falls, facilitating the movement of fluid and

electrolytes from the interstitium back into the vascular

space. The degree of this translocation is limited because as

fluid moves back into the capillaries, the albumin remain-

ing in the interstitium exerts an increased extravascular

osmotic pressure. Compensatory vasoconstriction facili-

tates this process because fluid can be recovered more

easily if the vascular space is collapsed than if it is dilated.

The degree of such translocation is probably limited to a

total of 1–2 L. This vascular refill accounts not only for

the decrease in intravascular osmotic pressure, but it is also

primarily responsible for the decline in hematocrit

observed in hypovolemic patients before resuscitation is

started.

Increased heart rate and contractility are important

homeostatic responses to hypovolemia. Both the direct

adrenergic response and the epinephrine secreted by the

adrenal medulla are responsible for these reflexes. Cardiac

output is the product of heart rate and stroke volume. It is

supported both by tachycardia and by translocated fluid.

Because blood pressure is the product of systemic vascular

resistance and cardiac output, peripheral vasoconstriction is

an essential factor in supporting blood pressure.

B. Metabolic Effects—Tissue metabolic pathways require

ATP as an energy source. Normally, ATP is produced

through the Krebs cycle via the aerobic metabolism of

glucose. Six molecules of oxygen are consumed when six

molecules of glucose are used to convert six molecules of

ADP into six molecules of ATP, CO

2

, and water. When

oxygen is not available, ATP is generated through anaero-

bic glycolysis, which not only yields smaller quantities of

ATP for the amount of glucose consumed but also pro-

duces lactic acid. This latter product is largely responsible

for the acidosis of ischemia. The point at which tissues

change from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism is defined

as the anaerobic threshold. This theoretic point varies

between tissues and clinical situations. .The most impor-

tant factor influencing the conversion to anaerobic gly-

colysis is oxygen availability.

The delivery of oxygen depends on the quantity of oxygen

present in the blood and the cardiac output. The former,

defined as the oxygen content, is calculated as follows:

Ca

O

2

= 1.34 × Hb × Sa

O

2

+ (0.0031 × Pa

O

2

)

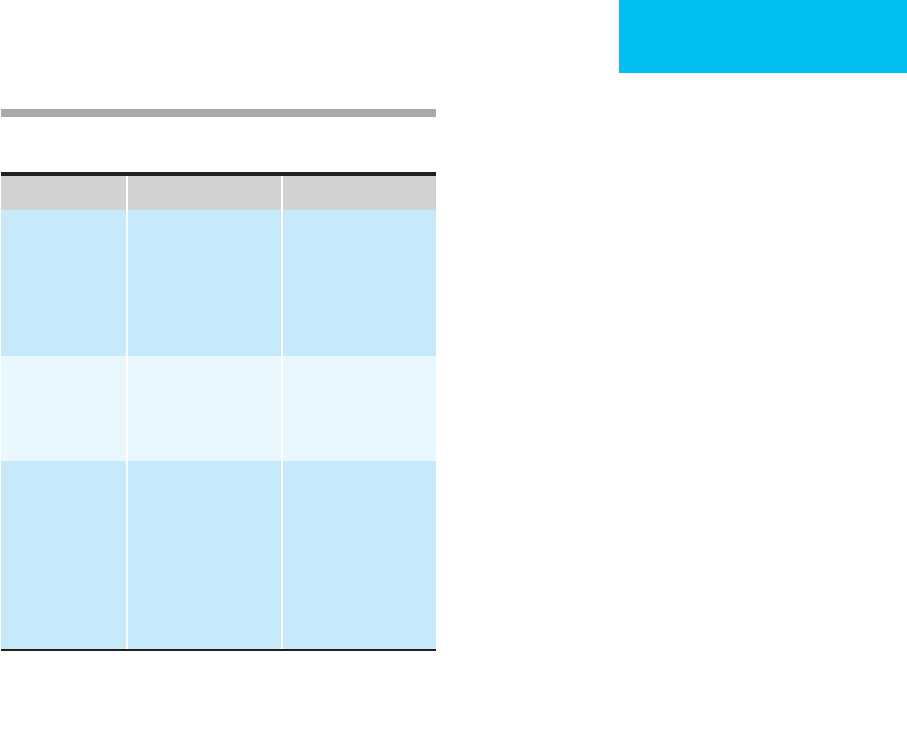

Pathophysiology Clinical Features

Mild (<20% of

blood volume)

Decreased perfusion of

organs that are able to

tolerate ischemia (skin,

fat, skeletal muscle,

bone). Redistribution of

blood flow to critical

organs.

Subjective complaints

of feeling cold. Postural

changes in blood pres-

sure and pulse. Pale,

cool, clammy skin. Flat

neck veins.

Concentrated urine.

Moderate (deficit =

20–40% of blood

volume)

Decreased perfusion of

organs that withstand

ischemia poorly (pan-

creas, spleen, kidneys).

Subjective complaint of

thirst. Blood pressure is

lower than normal in

the supine position.

Oliguria.

Severe (deficit >

40% of blood

volume)

Decreased perfusion of

brain and heart.

Patient is restless, agi-

tated, confused, and

often obtunded. Low

blood pressure with a

weak and often thready

pulse. Tachypnea may

be present. If allowed

to progress, cardiac

arrest results.

From Holcroft JW, Wisner DH: Shock and acute pulmonary failure

in surgical patients. In: Current Surgical Diagnosis and

Treatment, 9th ed. Way LW (editor). Originally published by

Appleton & Lange. Copyright © 1991 by the McGraw-Hill

Companies, Inc.

Table 11–1. Pathophysiology and clinical features of

hypovolemia.

CHAPTER 11

224

where Ca

O

2

is arterial oxygen content (in milliliters per

deciliter), Hb is hemoglobin concentration (in grams per

deciliter), Sa

O

2

is hemoglobin saturation of arterial blood (in

percent), and Pa

O

2

is partial pressure of dissolved oxygen in

arterial blood (in millimeters of mercury).

The principal determinants of oxygen content are the

concentration of hemoglobin and its saturation. Although

Pa

O

2

is the most commonly used indicator of oxygenation,

the dissolved oxygen component contributes only minimally

to oxygen content in patients with normal hemoglobin con-

centration and saturation. When anemia is profound, the rel-

ative contribution of dissolved oxygen increases. Systemic

oxygen delivery is defined as follows:

D

O

2

= Ca

O

2

× CO × 10

where D

O

2

is systemic oxygen delivery (in milliliters per

minute), Ca

O

2

is arterial oxygen content (in milliliters per

deciliter), and CO is cardiac output (in liters per minute).

Normally, D

O

2

is in excess of 1000 mL/min. When cardiac

output falls with hypovolemic shock, D

O

2

declines as well.

The extent depends not only on the cardiac output but also

on the fall in hemoglobin concentration. As oxygen delivery

declines, most organs increase their extraction of oxygen

from the blood they receive and return relatively desaturated

blood to the venous circuit. Systemic oxygen consumption is

calculated by rearranging Fick’s equation:

.

V

O

2

= (a − v)D

O

2

× CO × 10

Systemic oxygen consumption is typically 200–260 mL O

2

per minute for a 70-kg patient under baseline conditions. The

arteriovenous oxygen content difference—(a – v)D

O

2

—is

approximately 5 ± 1 mL/dL under these conditions. With

hypovolemia, oxygen consumption remains remarkably con-

stant, although peripheral oxygen extraction increases, result-

ing in an increase in (a – v)D

O

2

to values typically greater than

7 mL/dL. The oxygen extraction ratio (O

2

ER), which is defined

as

.

V

O

2

/D

O

2

, is also augmented. Increased (a – v)D

O

2

and O

2

ER

are metabolic hallmarks of hypovolemic shock.

Tissues vary greatly in their ability to increase oxygen

extraction. The normal extraction ratio is near 0.3 and may

increase to as much as 0.8 in conditioned athletes. The heart

and brain maximally extract oxygen under normal circum-

stances, making them extremely flow-dependent. Peripheral

oxygen consumption (

.

V

O

2

) remains essentially constant dur-

ing hypovolemia until a critical threshold is reached, at

which point increased extraction can no longer keep pace

with delivery. There is conflicting evidence about whether

oxygen consumption decreases in the face of reduced oxygen

delivery in humans. This so-called pathologic supply

dependence may, however, occur in patients with distributive

shock and with acute respiratory distress stndrome (ARDS).

When circulating blood volume falls sufficiently, oxygen

delivery declines, and death occurs below a critical D

O

2

of

less than 8–10 mL O

2

per minute.

Compensated shock occurs when system oxygen delivery

falls below D

O

2,crit

, and anaerobic metabolism becomes more

prevalent. Cell function is maintained as long as the combina-

tion of aerobic and anaerobic metabolism provides adequate

ATP. Tissues vary greatly in their resistance to hypoxia. While

the brain may tolerate only brief intervals, skeletal histiocytes

may withstand up to 2.5 hours of ischemia. Significantly, the

gut appears to be very sensitive to decreased perfusion.

Uncompensated shock, which results in tissue damage, occurs

when combined aerobic and anaerobic metabolism is not

adequate to sustain cellular function. Loss of cellular mem-

brane integrity results in cell swelling and ultimate cell death.

C. Neuroendocrine Effects—Adrenergic discharge and the

secretion of vasopressin and angiotensin are neuroendocrine

compensatory mechanisms that together produce vasocon-

striction, translocation of fluid from the interstitium into the

vascular space, and maintenance of cardiac output.

1. Secretion of aldosterone and vasopressin—

Together these hormones increase renal retention of salt and

water to assist in maintaining circulating blood volume.

2. Secretion of epinephrine, cortisol, and glucagon—

These hormones increase the extracellular concentration of

glucose and make energy stores available for cellular metab-

olism. Fat mobilization is increased. Serum insulin levels are

decreased.

3. Endorphins—Although their exact role is unclear, these

endogenously occurring opioids are known to decrease pain.

They promote deep breathing, which might increase venous

return by decreasing intrathoracic vascular resistance.

Endorphins have a vasodilatory effect and actually may

counteract the sympathetic influence.

D. Cellular and Immunologic Effects—Although sepa-

ration of shock and resuscitation into cellular and

immunologic effects is somewhat artificial, the distinction

provides a useful framework for the subsequent discus-

sion of resuscitation.

1. Cellular effects—Injured cells die by either apoptosis

or necrosis. Apoptosis requires energy and is a more con-

trolled than simple necrosis. Although apoptosis is required

for homeostasis, an increase in apoptosis may indicate cellu-

lar injury and organ dysfunction. Recent research has shown

that the type of resuscitation fluid used may have a signifi-

cant effect on the extent of apoptosis. Additionally, the extent

of apoptosis varies between cell types and may be particu-

larly significant in the CNS and brain.

Recent research has shown that the fluid used for resus-

citation also has an effect on cellular function. Some of the

factors thought to exert an influence include (1) the elec-

trolyte composition of the fluid used, (2) tonicity, (3) duration

of resuscitation, (4) type of cells exposed, (5) concurrent

inflammation or infection, (6) presence of additional

periods of shock or infection/contamination (“second hit”),

and (7) timing of resuscitation.

SHOCK & RESUSCITATION

225

2. Immunologic effects—Hypovolemic shock initiates a

series of inflammatory responses that may have deleterious

effects. Stimulation of circulating and fixed macrophages

induces the production and release of tumor necrosis factor

(TNF), which, in turn, leads to production of neutrophils,

inflammation, and activation of the clotting cascade.

Neutrophils are known to release free oxygen radicals, lyso-

somal enzymes, and leukotrienes C

4

and D

4

. These mediators

may disrupt the integrity of the vascular endothelium and

result in vascular leaks into the interstitial space. Activated

complement and products of the arachidonic acid pathway

serve to augment these responses.

Adhesion molecules are glycoproteins that cause leuko-

cyte recruitment and migration after hemorrhagic shock.

The most frequently involved cell adhesion molecules are the

selectins, integrins, and immunoglobulins. Although the

roles of the adhesion molecules are still under investigation,

some authorities have reported a correlation between the

severity of injury and the release of soluble cell adhesion

molecules (SCAMs). Others also have noted a relationship

between the development of multiple-organ failure and the

expression of SCAMs. The feasibility of using monoclonal

antibodies to SCAMs—as well as pathway blockade—is

under study. Isotonic crystalloid resuscitation fluids, as well

as some artificial colloids, have been demonstrated to pro-

duce an oxidative burst and the expression of adhesion mol-

ecules on neutrophils in a dose-dependent manner. Natural

colloids, such as albumin, did not create such a burst, and the

use of hypertonic saline has been shown to suppress some

neutrophil functions.

Oxygen metabolites, including superoxide anions, hydro-

gen peroxide, and hydroxyl-free radicals, are produced when

oxygen is incompletely reduced to water. These radical inter-

mediates are extremely toxic because of their effects on lipid

bilayers, intracellular enzymes, structural proteins, nucleic

acids, and carbohydrates. Phagocytes normally generate oxy-

gen radicals to assist in killing ingested material.

Antioxidants protect surrounding tissue if these compounds

leak from the phagocytes. Ischemia, followed by reperfusion,

has been shown to accelerate the production of toxic oxygen

metabolites independently of the activity of inflammatory

cells. This ischemia-reperfusion syndrome may lead to exten-

sive destruction of surrounding tissue and may play a signif-

icant role in determining the ultimate outcome of an episode

of hypovolemic shock.

Animal experiments have identified a number of other

potentially important immunologic responses to hypov-

olemia, including failure of antigen presentation by Kupffer

cells in the liver and translocation of bacteria from the gut

into the systemic circulation. This latter mechanism may

explain the occurrence of sepsis after hypotension without

other sources of infection.

E. Renal Effects—Blood flow to the kidneys decreases

quickly with hypovolemic shock. The decline in afferent flow

causes glomerular filtration pressure to fall below the critical

level required for filtration into Bowman’s capsule. The kid-

ney has a high metabolic rate and requires substantial blood

flow to maintain its metabolism. Therefore, sustained

hypotension may result in tubular necrosis.

F. Hematologic and Thrombotic Effects—When hypov-

olemia is due to loss of fluid volume without loss of red

blood cells, which occurs with emesis, diarrhea, or burns, the

intravascular space becomes concentrated, with increased

viscosity. This sludging may lead to microvascular thrombo-

sis with ischemia of the distal bed.

G. Neurologic Effects—Sympathetic stimulation does not

cause significant vasoconstriction of the cerebral vessels.

Autoregulation of the brain’s blood supply keeps flow con-

stant as long as arterial pressure does not decrease to less

than 70 mm Hg. Below this level, consciousness may be lost

rapidly, followed by decline in autonomic function.

H. Gastrointestinal Effects—Hypotension causes a decrease

in splanchnic blood flow. Animal models have shown a rapid

decrease in gut tissue oxygen tension, which may lead to the

ischemia-reperfusion syndrome or to translocation of intes-

tinal bacteria. Increased concentrations of xanthine oxidase

occur within the mucosa and also may be responsible for

bacterial translocation. Pentoxifylline has aroused recent

interest as a potential agent for increasing intestinal

microvascular blood flow after periods of ischemia.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—The findings associated with

hypovolemic shock vary with the age of the patient, the pre-

morbid condition, the extent of volume loss, and the time

period over which such losses occur. The physical findings

associated with different degrees of volume loss are summa-

rized in Table 11–1. Heart rate and blood pressure measure-

ments are not always reliable indicators of the extent of

hypovolemia. Younger patients can easily compensate for

moderate volume loss by vasoconstriction and only minimal

increases in heart rate. Furthermore, severe hypovolemia can

result in bradycardia as a preterminal event. Orthostatic

blood pressure testing is often helpful. Normally, transition

from the supine to the sitting position will decrease blood

pressure by less than 10 mm Hg in a healthy person. When

hypovolemia is present, the decline is greater than 10 mm Hg,

and the pressure does not return to normal within several

minutes. Older patients who present with apparently normal

blood pressures while supine often become hypotensive

when brought to an upright position. Such testing must be

used with caution in patients who have sustained multiple

injuries because potentially unstable vertebral injuries may

be present.

Decreased capillary refilling, coolness of the skin, pallor,

and collapse of cutaneous veins are all associated with

decreased perfusion. The extent of each depends on the

severity of the underlying shock. These findings are not spe-

cific to hypovolemic shock and may occur with cardiac shock

CHAPTER 11

226

or shock from pericardial tamponade or tension pneumoth-

orax. Collapsed jugular veins are commonly found in hypo-

volemic shock, although they also may occur with cardiac

compression in a patient who is not adequately fluid-

resuscitated. Examination of the jugular veins is best per-

formed with the patient’s head elevated to 30 degrees. A

normal right atrial pressure will distend the neck veins

approximately 4 cm above the manubrium.

Urine output is usually markedly decreased in patients

with hypovolemic shock. Oliguria in adults is defined as

urine output of less than 0.5 mL/kg per hour. If oliguria is

not present in the face of clinical shock, the urine should be

examined for the presence of osmotically active substances

such as glucose and radiographic dyes.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory studies may be useful

in determining the cause of hypotension. However, resuscita-

tion of a patient in shock should never be withheld pending

the results of laboratory determinations.

The hematocrit of a patient in hypovolemic shock may be

low, normal, or high depending on the cause and duration of

shock. When blood loss has occurred, evaluation prior to

capillary refill by interstitial fluid will yield a normal hemat-

ocrit. On the other hand, if the patient has bled slowly, if

recognition is delayed, or if fluid resuscitation has been insti-

tuted, the hematocrit will be low. When hypovolemia results

from loss of nonsanguineous fluid (eg, emesis, diarrhea, or

fistulas), the hematocrit is usually high. A crude way to esti-

mate the extent of blood loss is to assume that the intravas-

cular space is a single compartment and that the change in

hemoglobin concentration is proportional to the extent of

blood loss and fluid replacement with nonsanguineous flu-

ids. Where H

i

is the (presumed) initial hematocrit, H

f

is the

final hematocrit, and EBV is the approximate circulating

blood volume (approximately 70% of the body weight in an

adult), the estimated blood loss (EBL) may be calculated as

EBL = EBV

× ln(H

i

/H

f

).

Lactic acid accumulates in patients with shock that is

severe enough to cause anaerobic metabolism. Both the extent

of elevation of arterial lactic acid and the rate at which it is

cleared with volume resuscitation and control of bleeding are

useful markers of the presence of ischemia and its resolution.

Failure to clear elevated arterial lactic acid is an indication of

inadequate resuscitation. If arterial lactic acid concentration

remains elevated despite seemingly appropriate fluid resusci-

tation, other causes of hypoperfusion should be sought.

Other nonspecific findings include decreased serum

bicarbonate and a minimally increased white blood cell

count. Base excess, calculated from an arterial blood gas

determination, indicates that portion on an acidosis that is

metabolic in nature. Some laboratories use the term base

deficit, which is simply the negative absolute value of the base

excess. Like lactic acid, base deficit should resolve with ade-

quate resuscitation.

C. Hemodynamic Monitoring—Assessment of central

venous pressure is seldom required to make the diagnosis of

hypovolemic shock. Because the decreased volume allows

venous collapse, insertion of central venous monitoring

catheters can be particularly hazardous. If the patient’s blood

pressure and mental status do not respond to fluid adminis-

tration, a continued source of bleeding should be suspected.

Central venous pressure monitoring may be useful in older

patients with a known or suspected history of congestive

heart failure because excessive fluid administration may rap-

idly result in pulmonary edema. In extreme cases, a pul-

monary artery flotation catheter may be required to optimize

fluid status.

Capnographic monitoring will reflect a decrease in end-

tidal CO

2

. This is produced by a decrease in blood flow to the

lungs. When compared with arterial blood gases, a widening

of the arterial–end-tidal CO

2

gradient is apparent. If pul-

monary function is normal, only minimal changes in arterial

hemoglobin saturation will be present. Hence pulse oximetry

indicates normal saturation. The introduction of noninvasive

transcutaneous tissue oxygen probes, which use near-infrared

spectroscopy to measure subcutaneous tissue oxygen tension

(St

O

2

), holds promise as a simple bedside method for deter-

mining the adequacy of resuscitation. A pilot study showed

that trauma patients who maintained St

O

2

above 75% within

the first hour of ED arrival had an 88% chance of surviving

without multiple-organ dysfunction.

Differential Diagnosis

Shock owing to hypovolemia may be confused with shock

from other causes (Table 11–2). Cardiac shock produces

signs similar to those found with hypovolemia, with the

exception that neck veins are usually distended. Absence of

such distention may be due to inadequate fluid resuscitation.

Central venous pressure monitoring will help to make the

differentiation. Following trauma, peripheral vasodilation

owing to spinal cord injury may produce shock that is rela-

tively resistant to fluid administration. Hypovolemia is the

primary cause of shock in trauma victims, and it should

never be assumed that other causes are responsible until fluid

in adequate amounts has been administered.

Alcoholic intoxication may make the diagnosis of hypov-

olemia difficult. Serum ethanol elevation causes the skin to be

warm, flushed, and dry. The patient usually makes dilute

urine. These patients may be hypotensive when supine, with

exaggerated postural blood pressure changes. Hypoglycemic

shock owing to excessive insulin administration is not uncom-

mon in the ICU. The patients are cold, clammy, oliguric, and

tachycardiac.A history of recent insulin administration should

arouse suspicion of hypoglycemic shock. After samples have

been taken for blood glucose determinations, intravenous

administration of 50 mL 50% glucose should improve the

situation.

Treatment

A. General Principles—Unlike acute posttraumatic situa-

tions, resuscitation of patients with hypovolemic shock in