Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.3 Stratification and Bedforms

95

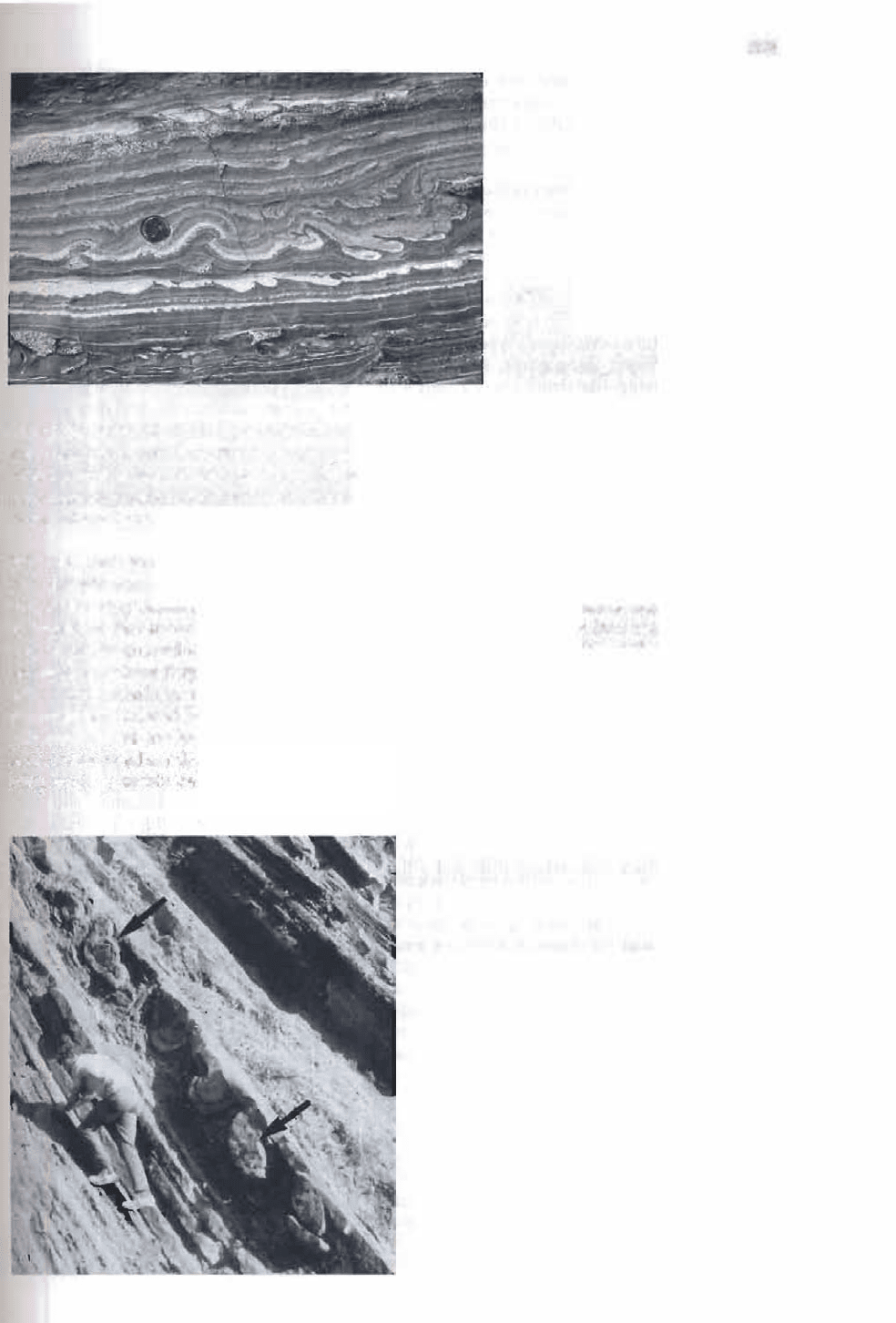

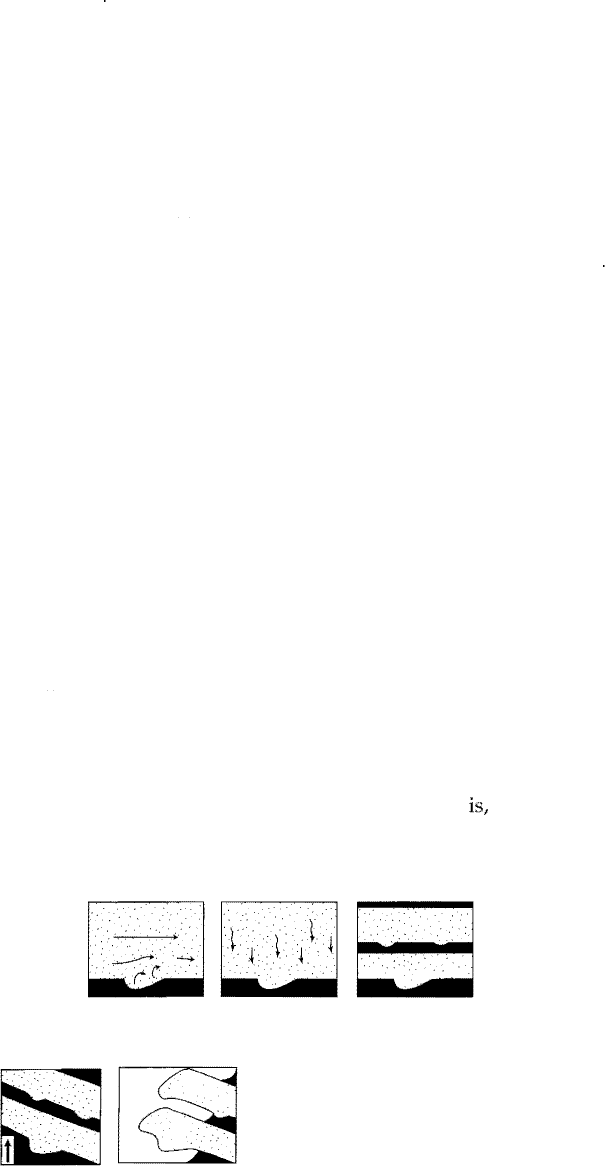

Figure 4.27

Flame structures in a thin-bedded, fine sandstone

shale succession, Elkton Siltstone, southwestern

Oregon. The best developed flames are in the layer

immediately below the coin.

caused by sediment loading. They are probably caused mainly by loading of

water-saturated mud layers which are less dense than overlying sands and are

consequently squeezed upward into the sand layers. The orientation of over

tued crests suggests that loading may be accompanied by some horizontal drag

or movement between the mud and sand bed.

Ball and Pillow Structures. Ball and pillow structures are present in the lower

part of sandstone beds, and less commonly in limestone beds, that overlie shales

(fig. 4.28). They consist of hemispherical or kidney-shaped masses of sandstone

or

limestone that show internal laminations. some hemispheres, the laminae

may be gently curved or deformed, particularly next to the outside edge of the

hemispheres where they tend to conform to the shape of the edge. The balls and

pillows may remain connected to the overlying bed, as Figure 4.28, or they may

be completely isolated from the bed and enclosed in the underlying mud. Ball and

p

iow structures are believed to form as a result of foundering and breakup of

semiconsolidated sand, or limy sediment, owing to partial liquefaction of under

lying mud, possibly caused by shocking. Liquefaction of the mud causes the

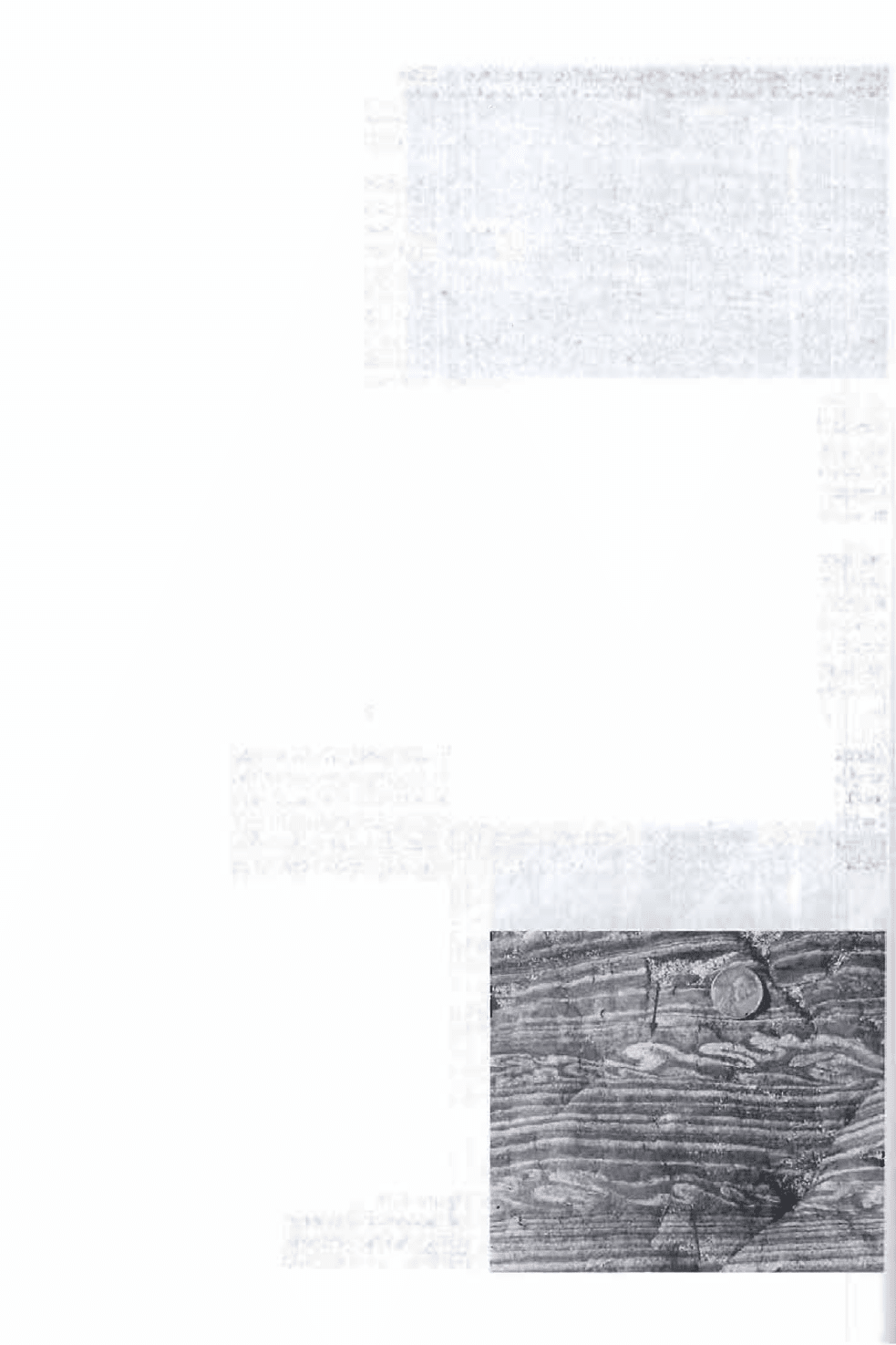

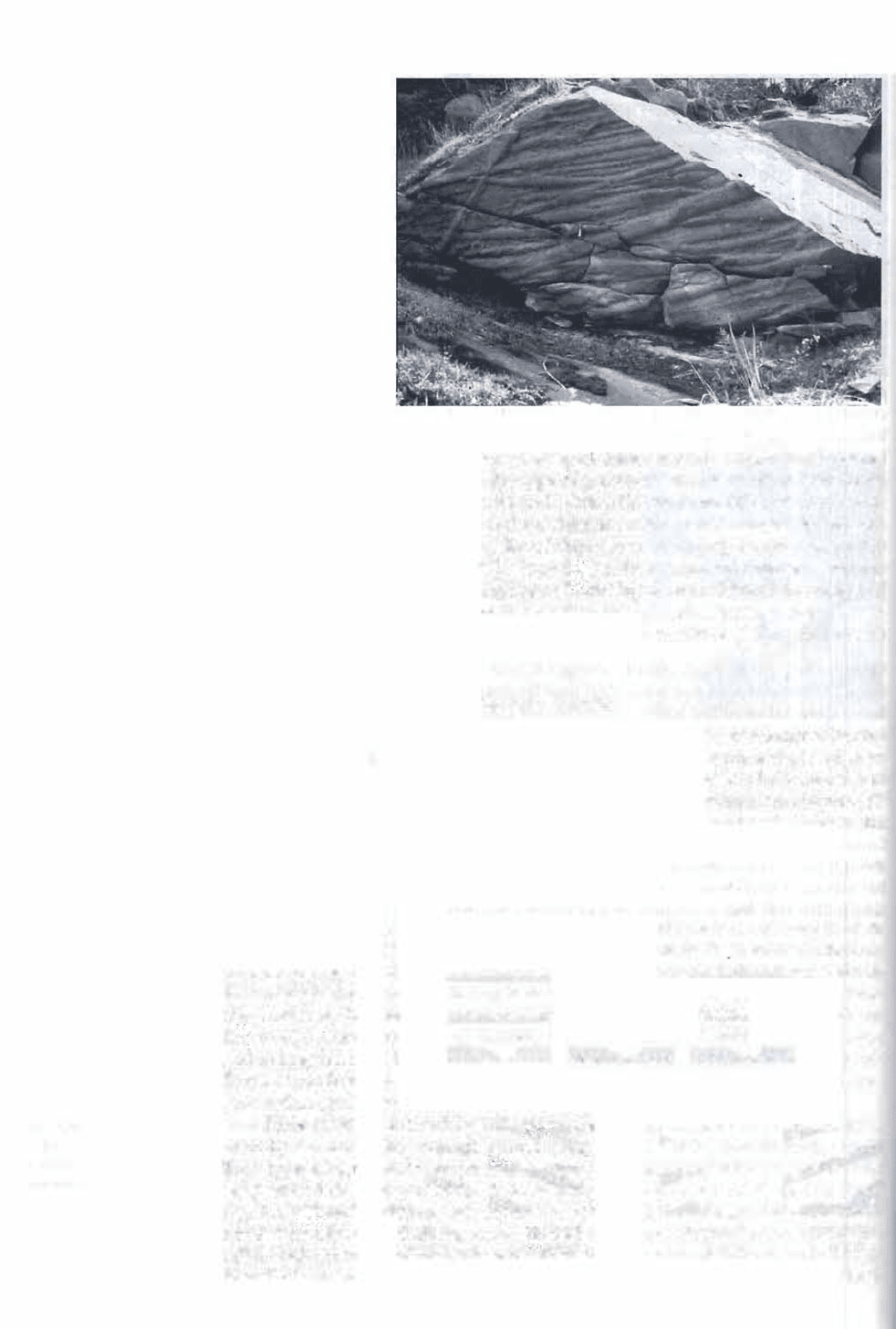

Figure 4.28

Ball and pillow structures (arrows) on the base of a thin,

steeply dipping sandstone bed. Lookingglass Formation

(Eocene), near lllahe, southwestern Oregon.

96

C11apter 4 I Sedimenta Structures

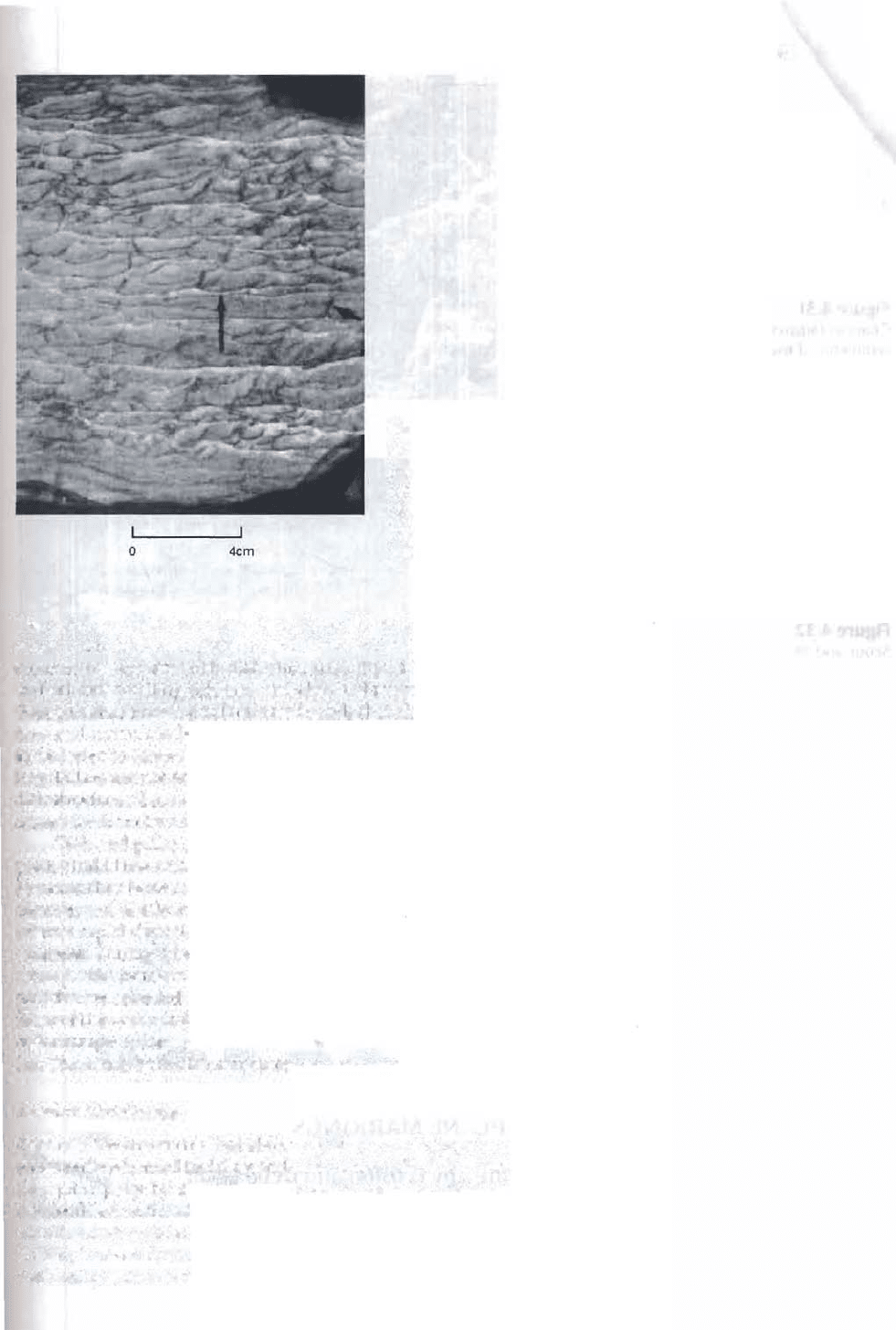

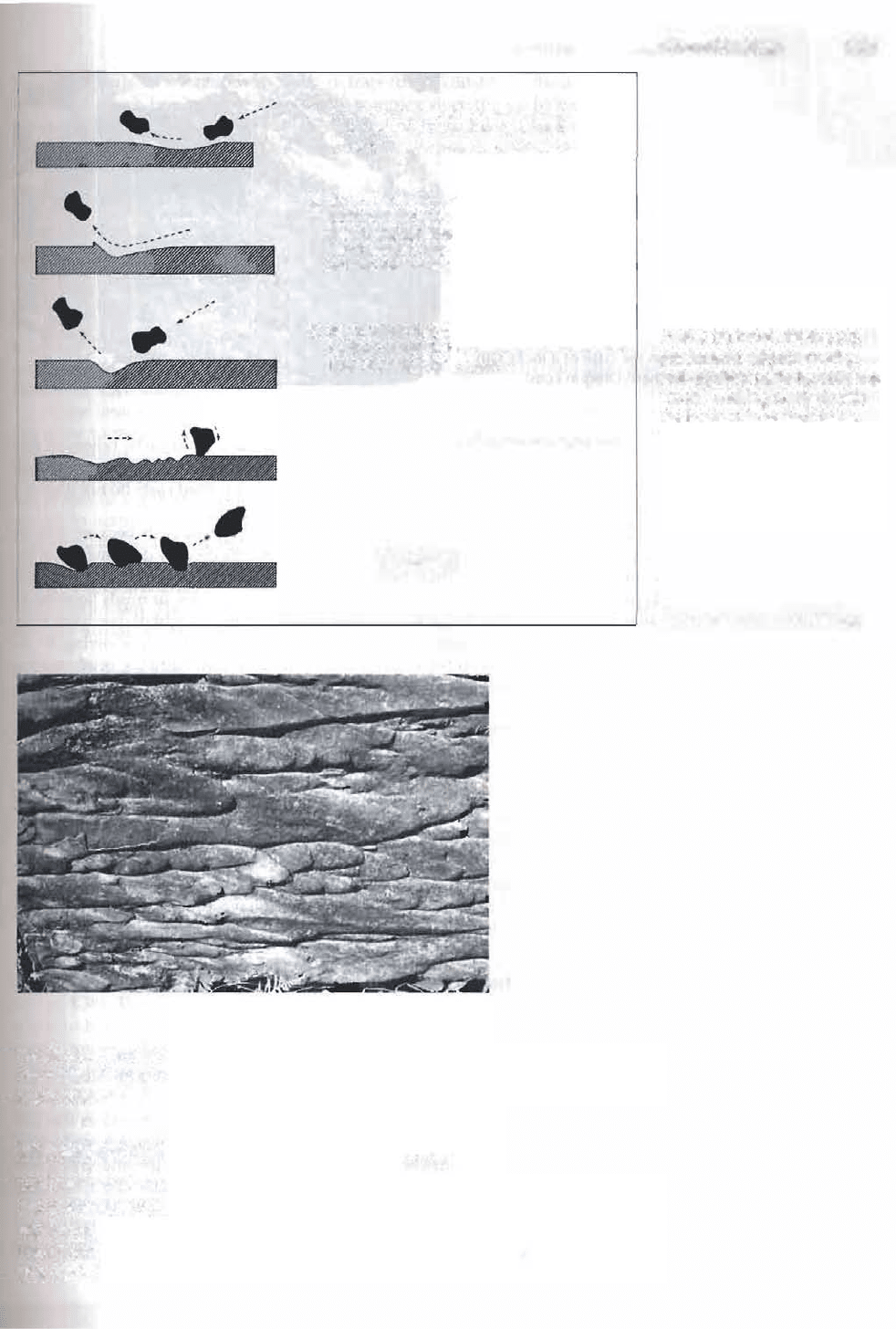

Figure 4.29

overlying sand beds or limy sediment to deform into hemispherical masses that

may subsequently break apart from the bed and sink into the mud. Kuenen (1958)

e

xperimentally produced

structmes that closely resemble natural ball and pillow

structures by applying a shock to a layer of sand deposited over thixotropic clay.

Synsedimentary Folds and Faults. The general term slump structures has been ap

plied to structures produced

by penecontemporaneous deformation resulting

from movement and displacement of unconsolidated or semiconsolidated sedi

ment, mainly under the inuence of gravity. Potter and Pettijolu1 (1977) describe

slump structures as being the products of either (1) pervasive movement involv

ing the interior of the transported mass, producing a chaotic mixture of dferent

types of sediments, such as broken mud layers embedded in sandy sediment, or

(2) a decollement type of movement in which the lateral displacement is concen

trated along a sole, thus producing beds that are tightly folded and piled into

nappelike structures (e.g., Fig. 4.29).

Slump structures may involve many sedimentation wuts, and they are com

monly faulted. Thicknesses of slump units have been reported to range from less

than 1 m to more than SO m. Slump units may be bounded above and below by

strata that show no evidence of deformation. It may be difficult in some strati

graphic successions, hO\'I'ever, to differentiate between slump units and incompe

tent beds such as shale that were deformed between competent sandstone or

limestone beds during tectonic folding .

Slump structures typically occur mudstones and sandy shales and less

commonly in sandstones, limestones, and evaporites. They are generally found in

w1its that were deposited rapidly, and they have been reported from a variety of

en

vironments where rapid sedimentation and oversteepened slopes lead to insta

bility. They occur glacial sediments, varved silts and clays of lacustrine origin,

eolian dune sands, turbidites, delta and reef-front sediments, subaqueous dune

sediments, and in sediments from the heads of submarine canyons, continental

shelves, and the walls of deep-sea trenches.

Dish and Pillar Structures. Dish structures are thin, dark-colored, subhorizontal,

flat to concave-upward, clayey laminations (Fig. 4.30) that occur principally

sandstone

and siltstone units (Lovve and LoPiccolo, 1974; Rautman and Do�,

1977). The laminations are commonly only a few millimeters thick, but individual

dishes may range from 1 em to more than 50 em wide. They typically occur

thick beds where dish and pillar structures may be the only structures visible.

Small-scale decollement-type synsedimentary folds (arrows) in

thin, fine-grained sandstone layers interbedded with shale, Elk-

ton Siltstone (Eocene), southwestern Oregon.

·

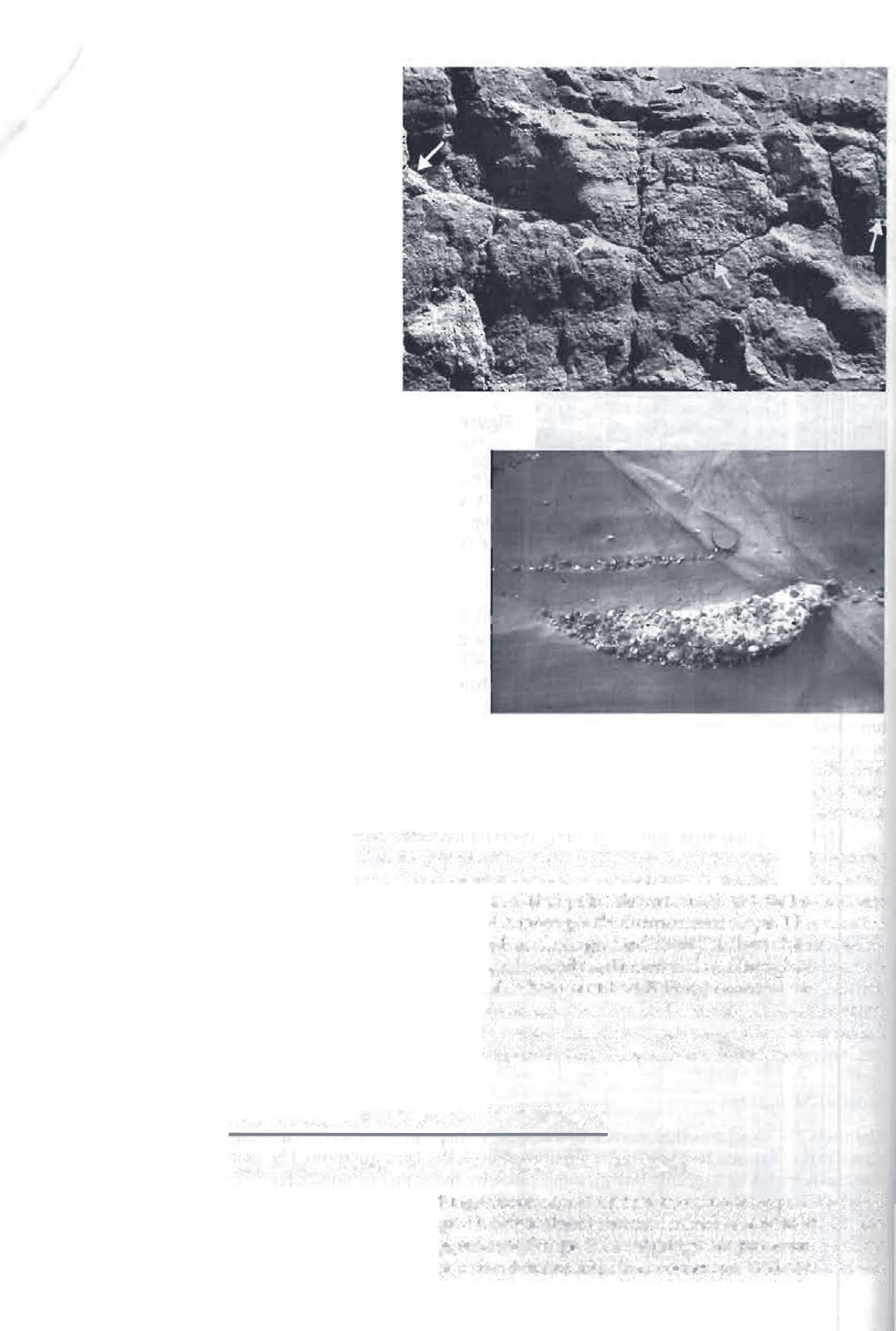

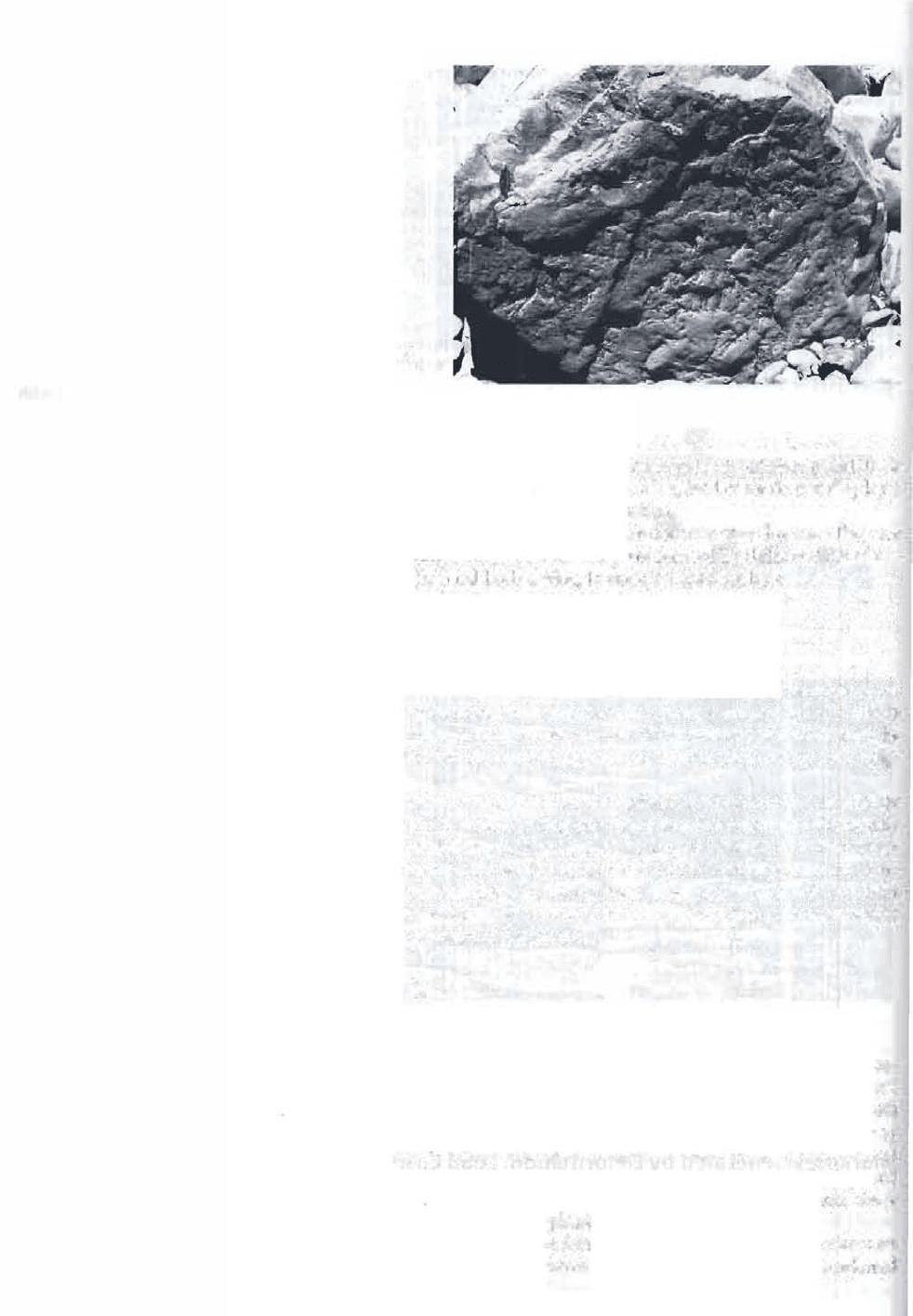

Figure 4.30

4.3 Stratification and Bedforms 97

Strongly curved to nearly flat dish structures (large arrow) and pillars

(small arrows) formed by dewatering of siliciclastic sediment, jack

fork Group (Pennsylvanian), southeast Oklahoma. [From lowe, D. R.,

1975, Water escape structures in coarse-grained sediment: Sedimen

tology, v. 22, Fig. 8, p. 175, reprinted by permission of Elsevier Sci

ence Publishers, Amsterdam.]

They also occur in beds less than about 0.5 m thick, where they commonly cut

ac ross primary flat laminations and other laminations. Pillar structures generally

c ur in association wth dish structures (Fig. 4.30). Pillars are vertical to near

vertical, cross-cutting cols and sheets of structureless or swirled sand that cut

thugh either massive or laminated sands that also commonly contain dish struc

tus and convolute laminations. They range in size from tubes a few millimeters

in diameter to large struch1res greater than 1 m in diameter and several meters

long. Pillars are not actually stratification structures. They are discussed here with

dish structures because of their close association with these structures and be

cause they form by a similar mechanism, discussed below.

Dish and pillar structures were first observed in sediment gravity-flow de

posits (turbidites and liquefied flows) and are most abundant in such deposits;

however, they have now also been reported in sediments from deltaic, alluvial, la

custrine, and shallow marine deposits, as well as from volcanic ash layers. They

indicate rapid depostion and form by escape of water during consolidation of

siment Dming gradual compaction and dewatering, semipermeable laminae

act as partial barriers to upward-moving water carrying fine sediment. The fine

particles are retarded by the laminae and are added to them, forming the dishes.

me of the water is forced horizontally beneath the laminations until it finds an

sier esape route upward. This forceful upward escape of water forms the pil

lars.llherefore, both dish structures and pillars are dewatering structures.

Erosion Structures

Channels are structure that show a U-shape or V-shape in cross section and cut

acrs earlier-formed bedding and lamination (Fig. 4.31). They are formed by ero

sion, principally by urrents but in some cases by mass movements. Channels

may be filled with sediment that is texturally different from the beds they trun

ca. Channels visible in outcrop range in width and depth from a few centimeters

to many meters. Even larger channels may be definable by mapping or drilling. It

seldom possible to trace their length in outcrop, but they can presumably extend

98 Chapter 4 I Sedimentary Structures

Figure 4.31

Channel (arrows) incised into fluvial, volcaniclastic

sediments of the Colestin Formation (Eocene),

Oregon-California border. Width of the channel is

-4 -Sm.

Figure 4.32

Scour-and-fill structures in Miocene sandstone, Blacklock Point,

southern Oregon coast. A small depression was scoured into

underlying sand by currents, then filled with gravel and sand.

Lens cap for scale.

for distances many times their width. Channels are very common fluvial and

tidal sediments. They also occur in turbidite sediments, where the long dimen

sions of the channels tend to be oriented parallel to current direction as shown by

other directional structures.

Scour-and-fill structures are similar to channels but are commonly smaller

(Fig. 4.32). They consist of smalL filled asymmetrical troughs a few centimeters to

a few meters in size, with long axes hat point downcurrent and that commonly

have a steep upcurrent slope and a more gentle downcurrent slope. They may

filled with either coarser grained or finer grained material than the substrate.

These structures are most common in sandy sediment and are thought to form as

a

result of scour by currents and subsequent backfilling as current velocity de

creases. contrast to channels, several scoUI-and-fill structures may occur to

gether closely spaced in a row. They are primarily structures of fluvial origin that

can occur river, alluvial-fan, or glacial outwash-plain environments.

4.4 BEDDING-PLANE MARKINGS

Markings Generated by Erosion and Deposition

Many bedding-plane markings o'cr on the underside of beds as positive-relief

casts and irregular markings. Owing to their location on the bases or sotes of beds,

they are often referred to ?S sole markings. Sole markings are preserved particu

larly well on the undersides of sandstones and other coarse grained sedimentary

4.4 Bedding-Plane Markings

99

cks that overlie shale beds. Many sole markings show directional features that

make them very useful for inteting e ow directions of ancient currents.

These so-called erosional sole markings are actually formed by a two-stage

pcess that involves both erosion and deposition. First, a cohesive, fine-sediment

bottom is eroded by some mechanism to produce grooves or depressions. Because

of

e cohesiveness of the sediment, the depressions may be preserved long

enough to be filled in and buried during subsequent deposition, typically by

coarser-grained sediment than the bottom mud. This coarser sediment is probably

deposited very shortly after erosion produced the depression, possibly in some

cases by the same current that formed the depression. After burial and lithifica

on, a positive relief feature is left attached to the base of the overlying bed. If the

bed subsequently undergoes tectonic uplift, these structures may be exposed by

weaering and subaerial erosion (Fig. 4.33). The initial erosional event that cre

ates the depressions in a mud bottom can take e form of current scour, or the de

pression can result from the action of objects called tools at are carried by the

cuent and intermittently or continuously make contact with the bottom. These

tools can be pieces of wood, the shells of organisms, or any similar object that can

be rolled or dragged along the bottom. Erosional structures may thus be classified

genetically as either current-formed structures or tool-formed structures.

Erosional sole markings are most common on the soles of turbidite sand

stones, but they are also present in sedimentary rocks deposited in other environ

ments. They can form in any environments where the requite conditions of an

erosive event followed reasonably quickly by a depositional event are met. They

have been reported in both fluvial and shelf deposits in addition to turbidites.

Groove Casts

Groove casts are elongate, nearly straight ridges that result from infilling of ero

sional relief produced as a result of a pebble, shell, piece of wood, or oer object

ing dragged or rolled across the surface of cohesive sediment (Fig. 4.34). They

ically range in width from a few millimeters to tens of centimeters and have a

lief of a few millimeters to a centimeter or two; however, much larger groove

casts also occur. Groove casts are greatly elongated in comparison to their width.

They are directional features that are oriented parallel to the flow direction of the

ancient currents that produced them; thus, they have paleocurrent significance.

Groove casts on the same bed commonly have the same general orientation, al

ough they may diverge at slight angles and even cross. Most groove casts do not

have features that show the unique flow diction; that we cannot tell from them

which direction was down current and which upcurrent. Chevrons are a variety of

Tectonic

tilting

Erosion of bed

�

.

r

l

�

·

·•

·

··•

·

>

.

·•

·

··.

·

•

·

.

.

.

t

Lt.·

·

... · ..

.

.

.

.

<

.

·

.

·

·

.

·

·

.

..

·. .

.

.

.

.

.

·

.'

.

.

.

·

. .

.

.

.

.

·

Deposition

Burial and

lithification

�

·

.

.

·

.

·

.

·

.

·

.

.

.

·

.

.

·

.

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

.

·

·

.

·

�

·

.

.

.

..

.

.

·

·

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

· ..•...

.

·

.

·.

·

·

·

···

·

·

·

·

·

·

•

.

...

.

.

•..

.

•

.

.

.

• .

.

·

.

·

·

.

.

·.

·

.··

·

·

.

.

••.•

.

•

.

...

·

·

.

.

.

.

...

.

.

.

.

.

··

·

·

.

.

.

·.

Subaerial

erosion

Tectonic

overturning

Subaerial

erosion

Figure 4.33

Postulated stages of development of sole

markings owing to erosion of a mud bottom

followed by deposition of coarser sediment.

The diagram also illustrates how the sole

markings appear as positive-relief features on

the base of the infilling bed after tectonic up

lift and subaerial weathering; it suggests how

sole markings can be used to tell top and

bottom of overturned beds. [From Collinson,

J. D., and D. B. Thompson, 1982, Sedimenta

structures, Fig. 4.1, p. 37, reprinted by

permission of George Allen & Unwin, Lon

don. Aer Ricci Lucchi, , 1970, Sedimen

tografia: Zanchelli, Bologna, Italy.]

1 00 Chapter 4 I Sedimentary Structures

Figure4.34

Large intersecting groove casts on th e base of a

turbidite sandstone bed, Fluornoy Formation

(Eocene), Oregon Coast Range.

groove casts made up of continuous V-shaped crenulations in which the V points

in a downstream direction; thus, this type of groove cast can be used to determine

the true direction of flow. Dzulyrtski and Walon (1965) suggest that chevrons are

formed by tools moving just above the sedimeul surface but not touching the sur

face, causing rucking-up of the ides of e groove. Groove casts are especially

common on the soles of turbidite beds owing to shell fragments, pieces of wood,

or other tools that are carried in th� base of turbidity current flows being dragged

across a mud bottom. They occur also on the soles of beds deposited in shallow

water environments such as tidal flats and flood plains where floating tools may

touch bottom and leave grooves.

Bounce, Brush, Prod, Roll, and Skip Marks

Small gouge marks are produced by tools that make intermittent contact with the

bottom, creating small marks. Brush and prod marks are asymmetrical in cross

sectional shape, and the deeper, broad part of the mark is orieflted downcurrent.

Bounce marks are roughly symmetrical. Roll and skip marks are formed hy a tool

bouncing up and down or rolling over the surface to produce a continuous track.

The genesis of these structures is illustrated in Figure 4.35.

Flute Casts

Flute casts are elongated welts or ridges that have a bulbous nose at one end that

flares out in the other direction and merges gradually with the surface of the bed

(Fig. 4.36). They occur singly or in swarms in which all of the flutes are oriented in

the same general direction. On a given sole, the flutes tend to be about the same

s�ze; however, ute casts on different beds can range in width hom a centimeter or

two to 20 em or more, in height (relief) from a few centimeters to 10 em or more,

and in length from a few centimeters to a meter or more. The plan-view shape of

flutes varies from nearly streamline, bilaterally symmetrical forms to more elon

gate and irregular forms, some of which are highly twisted.

flute casts are formed by filling

.

of a depression scoured cohesive sedi

ment by current eddes created behind some obstacle, or by chance eddy scour.

This type of curren scour produces asymmetrical depressions in which the

steepest and deepest part of the depression is oriented upstream or upslope (see

Fig. 4.33). Therefore, when such depressions are filled, the filling forms a positive

relief struetUJe with a bulbous nose oriented upstream. Flute casts thus make ex

ceUent paleocurrent 1dicators because they show the unique direction of current

flow. Flutes are particularly prevalent on the soles of turbidite sequences, but they

4.4 Bedding-Plane Markings

101

A

Bounce marks. The tool approaches the

sediment suace at a lo

w

angle and

immediately bounces back into the current.

B Brush marks. The tool approaches the

sediment surface at a very lo

w

angle,

w

ith the

axis ol the tool inclined upcurrent, and is then

lifted a

w

ay by the current, producing a ridge

of mud do

w

ncurrent of the mark.

C Pr marks. The tool reaches the sediment

suace at a fairl ligh angle and is then lifted

up and a

w

ay by the current.

D Roll marks. The tool rolls over the sediment

suace, producing a continuous roll mark.

E Skip marks. The tool travels do

w

ncurrent

w

ith

a sal tating movement, hitting the se diment

surface at nearly regular intervals.

Figure 4.36

Figure 4.35

Development in a cohesive

mud bottom of (A) bounce

marks, (B} bru marks, (C)

pr marks, (D) mil marks,

and (E) skip marks by action of

" tools" making contact with

the bott in various ways.

These tool-formed depressions

are subsequently filled with

coarser sediment to produce

positive-relief casts. [After Rei

neck, H. E., and I. B. Singh,

1 980, Depositional sedimenta

ry environments, 2nd ed., Fig.

127, 129, 125, 132,

p. 82, 83,

reprinted by permission of

Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.]

Flute casts on the base of a turbidite sandstone,

Fluornoy Formation (Eocene), Oregon Coast

Range. The bulbuous terminations of the flute

casts indicate that paleocurrent flow was from right

to left. [Photograph courtesy of Ewart Baldwin.]

a also present in sediments deposited in shallow marine and nomnarine envi

nmen

ts. They have been reported on

the soles of limestone beds as well as sand

stone beds.

Markings

Generated by Deformation: Load Casts

ad c a described by Potter and Pettijohn (1977) as "swellings ranging from

slight

bulges, deep or shallow rounded sacks, knobby excrescences, or highly ir

gular protuberance." They commonly occur on the soles of sandstone beds that

overlie mudstones or shales, and they tend to cover the entire bedding surface

(g. 4.37). They range in diameter and relief from a few centimeters to a few tens

1 02

Chapter 4 I Sedimentary Structures

Figure 4.37

Irregularly shaped load casts on the base of a loose slab

of Cretaceous sandstone, southern Oregon coast.

of centimeters. Load casts may superficially resemble flute casts; however, they

can be distinguished from flutes by their greater irregularity f shape and their

lack of definite upcurrent and downcurrent ends. Also, load casts do not dispfay a

preferred orientation with respect to current direction.

Although they are called casts, load casts are not true casts because they are

not fillings of a preexisting cavity or mold. They are formed by deformation of un

compacted, hydroplastic mud eds owing to unequal loading by overlying sand

layers. Uncompacted muds with excess fluid pore pressures, or muds liquefied by

an externally generated shock, can be deformed by the weight of overlying sand,

which may sink unequally into the incompetent mud. Loading owing to un

equal weight of the sand forces protrusions of sand down into the mud, creating

positive-relief features on the base of the sandstone beds that may resemble some

erosional structures, as mentioned. Load casts are closely related genetically to

ball and pillow structures and flame structures. Flute and groove casts may

modified by loading, wch tends to exaggerate their relief and destroy their orig

inal shapes.

Load casts can form in any environment where water-saturated muds are

quickly

buried by sand before

dewatering can take place. They do not indicate an}'

particular environment, although they tend to be most common in turbidite

quences. Their presence on the bases of some beds and not on others seems to re

flect the hydroplastic state of the nnderlying mud. They apparently will not form

on the bases of sand beds deposited on muds that have already been compacted or

de,atered prior to deposition of the sand.

Biogenic Structures

T ce Fossils

The burrowing, boring, feeding, and locomotion activities of organisms can pro

duce a variety of trails, depressions, and open burrows and borings in mud or senti

consolidated sediment bottoms. Filling of these depressions and burrows with

sediment of a different type or with different packing creates structures that may

be either positive-relief features, such as trails on the bases of overlying

beds, or

features that shmv up as burrow or bore fillings on the tops of the underlying mud

bed. Bu rrows and borings commonly extend down into beds; therefore, the

structures are not exclusively bedding-plane structures.

Tr acks, trails, burrows, borings, and other structures made by organisms on

bedding surfaces or within beds known collectively as trace fossils, also referred

4.4 Bedding-Plane Markings

103

as ichnofosss, or lebensspuren. Study of trace fossils constitutes the discipline of

ichnology, which has become increasingly complex since the mid-1950s and has

spawned a massive body of literature. Several of these books are listed under

"Further Reading" at the end of this chapter.

nds ace Fossils. Trace fossils are not true bodily preserved fossils; that is,

ey

do not form by conversion of a skeleton into a body fossil. They are simply

structures that originated through the activities of organisms. Interpreted broadly,

biogenic structures can be considered to clude the following: (1) bioturbation

stctures (burrows, tracks, trails, root penetration structures), (2) biostratification

suctures (algal stromatolites, graded bedding of biogenic origin), (3) bioero

sion structures (borings, scrapings, bitings), and (4) excrement (coprolites, such as

fe cal pellets or fecal castings). Not all geologists regard biostratification structures

as ace fossils, and these structures are not commonly included in published dis

ssions of trace fossils.

Trace fossils are classified into ichnogenera on the basis of characteristics

at relate to major behavioral traits of organisms and are given generic names

as Ophiomorpha. Distinctive but less important characteristics are used to

identify ichnospecies, e.g., Ophiomorpha nodosa. Trace fossils are produced by a

host of mine organisms such as crabs, flatfish, clams, molluscs, worms, shrimp,

d eel. nonmarine environments, organisms such as insects, spiders, worms,

llipedes, snails, and lizards can produce a variety of burrows and tunnels; ver

brate organisms leave tracks; and plants leave root traces. The organisms that

puce traces are rarely preserved with the traces; thus, the trace maker is com

monly

not known. Therefore, the names applied to ichnogenera and ichnospecies

geray do not refer to the trace makers themselves.

ace Fossil Assemblages. From a sedimentological standpoint, study of trace-fossil

assemblages has commonly proven to be more useful than study of individual

icogenera or ichnospecies. A trace-fossil assemblage is a basic collective term

at embraces all of the trace fossils present within a single unit of rock Although

vaous kinds of trace-fossil assemblages are recognized, groupg of trace fossils

to ichnofacies has particular significance in paleoenvironmental studies.

Seilacher (1964, 1967) introduced the concept of ichnofacies to describe associa

of trace fossils that are recurrent in time and space and that reect environ

mental conditions such as water depth (bathymetry), salinity, and the nature of

e substrate in or on which they formed (e.g., mud vs. sand bottom). Fundamen

tly, ichnofacies are sedimentary facies defined on the basis of trace fossils, and

each inofacies may include several ichnogenera.

Seilacher (1967) established six ichnofacies, which he named after character

istic inogenera. Four of these (Skolithos, Cruziana, Zoophycos, and Nereites) were

based

on e marine water depth at which they were interpreted to occur (Table

4.3; Fig. 4.38). The Glossungites ichnofacies was established for traces that occur

to hard marine surfaces, and the Scoyenia ichnofacies characterized non

marine environments. Subsequently, Frey and Seilacher (1980) established the

Tpanites ichnofacies for hardgrounds and rockgrounds; Bromley, Pemberton,

d Rahmani (1984) proposed the Te redolites ichnofacies for borgs in wood

(woodgrou

nds); and Frey and Pemberton (1987) established the Psilonichus ichno

cies for softgrounds in the marine to nonmarine environment. Several addition

icofacies have also been proposed (e.g., Bromley, 1996, p. 241); however, the

ne inofacies shown in Ta ble 4.3 are most commonly used. Sedimentologists

parcularly interested in the Skolithos, Cruziana, Nereites, and Zoophycos ichno

facies, which have the greatest potential for interpreting ancient marine environ

mtal conditions.

.

g

b 4.3

Pp icfacies

-

Ichnofacies Substrate

Environment

Teredolites

Wood ground

Estuarine, nearshore

marine

Trypa nites

Rockground

Rocky coasts, reefs,

hard-grounds

Scoyenia

Firmground

Freshwater,

terrestrial

Clossi-

Firmground

Marine to nonmarine

fu ngites

Psilonic/m us

Softground

Marine to nonmarine

sand, mud

Skolithos

Softground Marine

sand

Cruziana

Softground

Marine

sand, mud

Zoophycos

Soft ground

Marine

mud

Nereites

Softground Marine

sand, mud

Water

depth

Various

Beach

Water

energy

Various

High

Medium

shelf

to low

Slope-abyssal Low

Slope-

Turbidity

abyssal

crent

event

Distinguishing characteristics

Club-shaped, stumpy to elongate, subcylindrical to subparallel borings

Cylindrical, tear-, or U-shaped, vertical to branching borings

Horizontal to curved or tortuous burrows; sinuous crawling traces; vertical

cylindrical to branching shafts; tracks and trails

Ve rtical, cylindrical, U- or tear-shaped borings and/ or densely branching

burrows

J-, Y-, or U-shaped burrows; vertical shafts and horizontal tunnels; tracks,

t

rails, root traces

Ve rtical, cylindrical, or U-shaped

very few horizontal burrows; low

Mixed association of vertical, inclined, and horizontal structures;

diversity of traces

Simple to moderately complex grazing and feeding structures; horizontal to

slightly inclined feeding or dwelling structures arranged in delicate sheets,

ribbons, lobes, or spirals

Complex horizontal, crawling, and grazing traces and patterned feeding/

dwelling traces; low diversity

Data from: Bromle

y

d al., 1984; Frey and Seilachr, 1980; Frty and P(• mbcrton, 1987; Pemrton ct a!., 12; Se ilacher, 1967.