Barber J.R. Intermediate Mechanics of Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

2.2 Failure theories for isotropic materials 45

U

0

=

¯

U

0

+

ˆ

U

0

, (2.39)

where

¯

U

0

=

3

¯

σ

2

(1 −2

ν

)

2E

=

(

σ

1

+

σ

2

+

σ

3

)

2

(1 −2

ν

)

6E

=

I

2

1

(1 −2

ν

)

6E

(2.40)

is the dilatational strain energy density and

ˆ

U

0

=

(

ˆ

σ

1

−

ˆ

σ

2

)

2

+ (

ˆ

σ

2

−

ˆ

σ

3

)

2

+ (

ˆ

σ

3

−

ˆ

σ

1

)

2

(1 +

ν

)

6E

=

(

σ

1

−

σ

2

)

2

+ (

σ

2

−

σ

3

)

2

+ (

σ

3

−

σ

1

)

2

(1 +

ν

)

6E

(2.41)

=

(I

2

1

−3I

2

)(1 +

ν

)

3E

(2.42)

is the deviatoric strain energy density. Deviatoric strain energy is sometimes referred

to as the strain energy of distortion or shear strain energy.

Von Mises’ theory states that yielding will occur when the deviatoric strain en-

ergy density reaches a critical value for the material — i.e.

ˆ

U

0

≡

(

σ

1

−

σ

2

)

2

+ (

σ

2

−

σ

3

)

2

+ (

σ

3

−

σ

1

)

2

(1 +

ν

)

6E

=

ˆ

U

Y

. (2.43)

The elastic region is then defined by the inequality

ˆ

U

0

<

ˆ

U

Y

.

Notice that using von Mises’ criterion, we don’t have to decide which of the

three stress differences (Mohr’s circle diameters) is the greatest. Instead, we just

square them (thereby ensuring a positive result) and add them. Von Mises’ criterion

is therefore easier to apply than Tresca’s, but it leads to non-linear equations.

Octahedral shea r stress

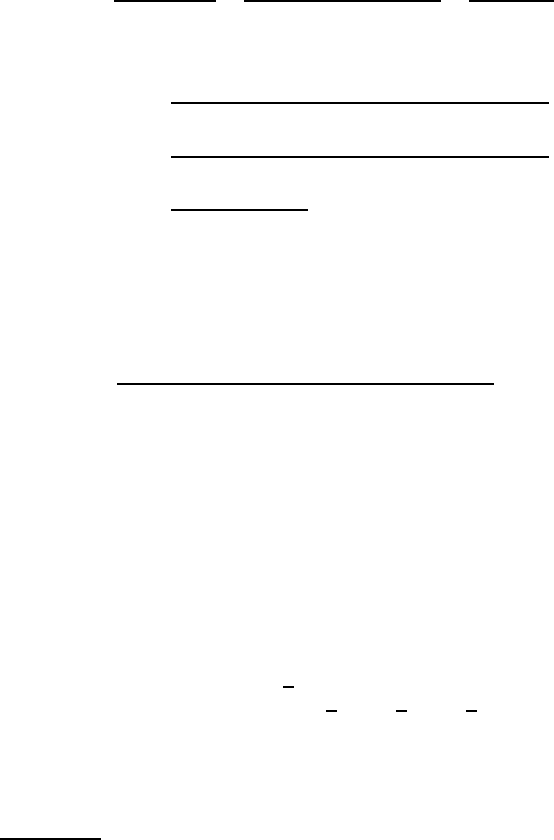

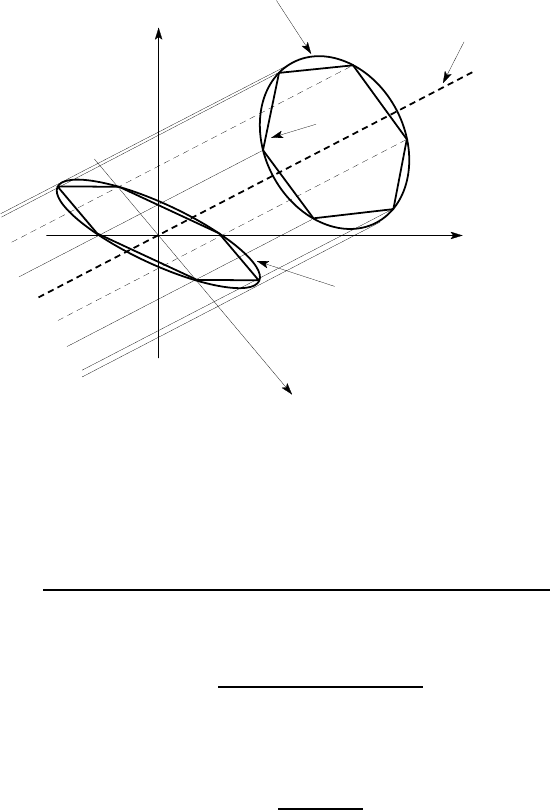

There exist eight octahedral planes which make equal angles with the three princi-

pal directions. If we define the x,y,z axes to coincide with the principal directions,

the three direction cosines of the normals to the octahedral planes must be of equal

magnitude and hence must be 1/

√

3, in view of (2.10). Thus, the octahedral planes

are defined by the set {l,m,n}= {±1/

√

3,±1/

√

3,±1/

√

3}. One of the octahedral

planes is illustrated in Figure 2.10. There are eight such planes in all and they define

a regular octahedron.

The normal stress and resultant shear stress on all these planes can be shown

17

to be given by

non-linear (quadratic) in the stresses. However, the algebra shows that the strain energy

density does in fact decompose in this way, indicating that the processes of dilatation and

distortion are orthogonal to each other. This implies that no work is done by a purely

deviatoric stress field during a change in volume without change in shape and conversely

that no work is done by a hydrostatic stress field during a distortion without dilatation.

17

See for example Boresi et al. (1993), equation (2.22).

46 2 Material Behaviour and Failure

σ

oct

=

¯

σ

=

I

1

3

(2.44)

τ

oct

=

1

3

q

(

σ

1

−

σ

2

)

2

+ (

σ

2

−

σ

3

)

2

+ (

σ

3

−

σ

1

)

2

=

1

3

q

2(I

2

1

−3I

2

) (2.45)

and are known as the octahedral normal stress and octahedral shear stress, respec-

tively.

2

3

(1,0,0)

(0,1,0)

(0,0,1)

1

Figure 2.10: The octahedral plane {l,m,n} = {1/

√

3,1/

√

3,1/

√

3}

Comparing these results with equation (2.43), we see that the von Mises theory

is mathematically equivalent to the statement that yielding will occur when the octa-

hedral shear stress reaches a critical value for the material. The von Mises theory is

therefore also sometimes referred to as the octahedral shear stress theory.

It is instructive to note that two essentially different measures of the severity of

a state of stress can lead to the same expression for the yield envelope. There is no

way that a set of experiments could determine which (if indeed either) of the octahe-

dral shear stress or the deviatoric strain energy density is most influential in causing

yielding.

18

All we can do is to observe the experimental shape of the yield envelope

(which is usually closely approximated by equation (2.43) for an isotropic ductile

material) and conclude that either of the two physical quantities provide plausible

physical ‘explanations’ of this observation. For design purposes, this is also all we

need to do. A mathematical or graphical description of the experimentally deter-

mined yield surface is sufficient to tell us whether a proposed state of stress is safe

or not.

18

The reader might like to ponder whether some different kind of experiment could be de-

vised that would enable the balance to be tilted in favour of one or other of these theories.

For example, would the theories predict the same yield envelope for an anisotropic material

and if not, what would the results of the corresponding test tell us?

2.2 Failure theories for isotropic materials 47

Equivalent tensile stress

The theories of Tresca and von Mises define the shape of the yield surface, so the

result of a single experiment is sufficient to define the surface completely. For exam-

ple, suppose we perform a uniaxial tensile test and determine the uniaxial yield stress

S

Y

for the material. It follows that the point (S

Y

,0,0) must lie on the yield surface

and this is sufficient to determine

τ

Y

=

S

Y

2

(2.46)

from (2.31) or

ˆ

U

Y

=

S

2

Y

(1 +

ν

)

3E

(2.47)

from (2.43).

It is convenient to define the equivalent tensile stress

σ

E

as that function of the

stress components that is equal to S

Y

on the yield surface. For example, we can

substitute (2.47) into (2.43) to restate von Mises’ criterion as

(

σ

1

−

σ

2

)

2

+ (

σ

2

−

σ

3

)

2

+ (

σ

3

−

σ

1

)

2

(1 +

ν

)

6E

=

(I

2

1

−3I

2

)(1 +

ν

)

3E

=

S

2

Y

(1 +

ν

)

3E

(2.48)

and hence

σ

E

≡

r

(

σ

1

−

σ

2

)

2

+ (

σ

2

−

σ

3

)

2

+ (

σ

3

−

σ

1

)

2

2

=

q

I

2

1

−3I

2

= S

Y

. (2.49)

A similar procedure with equations (2.46, 2.31) gives

σ

E

≡ max(|

σ

1

−

σ

2

|,|

σ

2

−

σ

3

|,|

σ

3

−

σ

1

|) = S

Y

(2.50)

for the Tresca criterion.

The formulations (2.49, 2.50) are very convenient for design purposes, since all

we need to do is to evaluate

σ

E

and compare it with tabulated values of the uniaxial

yield stress S

Y

. The concept of equivalent tensile stress also enables us to define a

safety factor against yield as

SF =

S

Y

σ

E

. (2.51)

If the stress components were increased proportionally, the safety factor is the ratio

by which they would need to be increased for yield to occur.

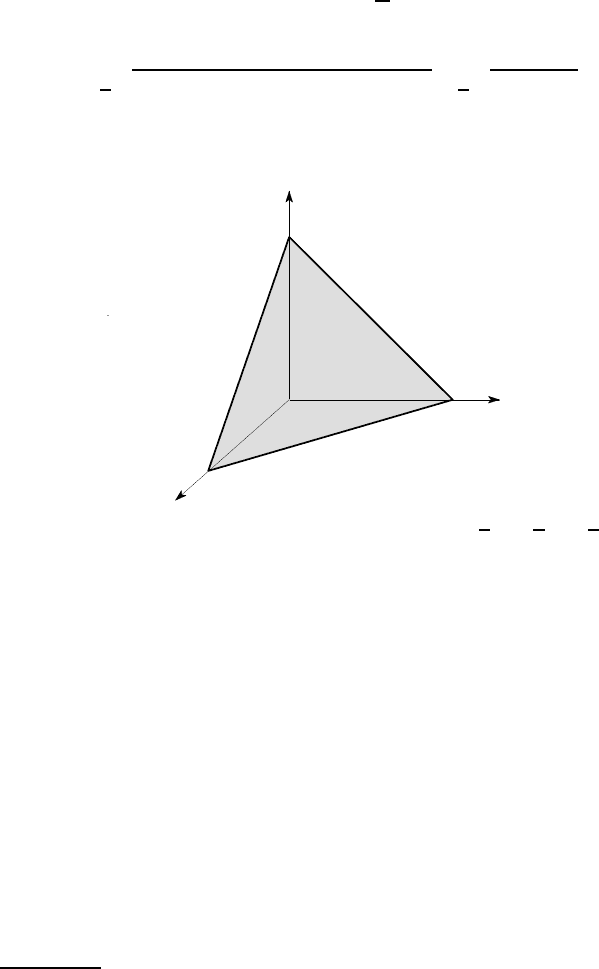

Graphical representation

In the case of plane stress (

σ

3

=0), the Tresca theory (2.50) reduces to

σ

E

≡ max(|

σ

1

−

σ

2

|,|

σ

2

|,|

σ

1

|) = S

Y

(2.52)

48 2 Material Behaviour and Failure

and the von Mises theory (2.49) to

σ

E

≡

q

σ

2

1

+

σ

2

2

−

σ

1

σ

2

= S

Y

. (2.53)

These expressions plot out as the hexagon and ellipse respectively in Figure 2.11.

σ

1

σ

2

S

Y

(0, )

S

Y

(0, )

S

Y

( , )

S

Y

S

Y

( ,0)

S

Y

( ,0)

S

Y

S

Y

( , )

O

Tresca

von Mises

Figure 2.11: Tresca and von Mises yield envelopes for plane stress

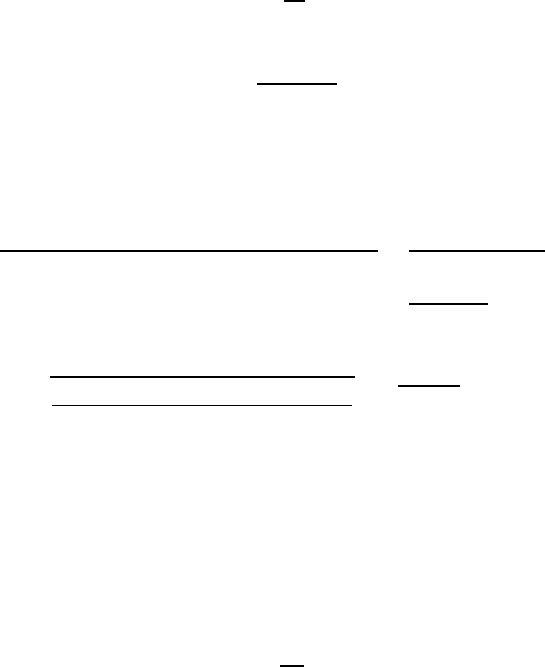

The corresponding three-dimensional yield envelope is a regular hexagonal

cylinder for the Tresca criterion and a circumscribed circular cylinder for von Mises’

theory, the axis in each case being the inclined line

σ

1

=

σ

2

=

σ

3

(which we know is

always in the safe region. These envelopes are illustrated in Figure 2.12.

The plane stress results of Figure 2.11 are simply the intersection of these reg-

ular three-dimensional surfaces with the plane

σ

3

= 0. Notice that in the three-

dimensional case, the von Mises criterion has the very simple graphical interpre-

tation that yielding occurs when the shortest distance in principal stress space to the

hydrostatic line

σ

1

=

σ

2

=

σ

3

exceeds a critical value. This value (the radius of the

cylinder in Figure 2.12) can be shown to be

p

2/3S

Y

.

Careful experiments for ductile materials such as metals tend to favour von

Mises’ theory over Tresca’s, but the difference is comparatively small and mostly lies

within the range of variability of material between one sample and another. Thus, in

practice, we use whichever theory is more convenient for design calculations. As we

explained above, Tresca’s criterion has the advantage of leading to linear equations

and hence to a simpler formulation in problems involving plasticity.

19

However, if

we simply wish to calculate a safety factor in design using equation (2.51), the von

Mises theory is more convenient since it involves the computation of a single alge-

braic expression.

19

See Chapters 5,9.

2.2 Failure theories for isotropic materials 49

σ

2

σ

1

Tresca

von Mises

the plane

σ = 0

3

σ

3

1

2

hydrostatic line

σ = σ = σ = 0

3

Figure 2.12: Tresca and von Mises yield envelopes for three-dimensional states of

stress

An additional advantage is that the von Mises equivalent tensile stress is stated

in terms of the stress invariants I

1

,I

2

and hence can be evaluated directly from the

stress components in a general coordinate system, without first finding the principal

stresses. Substituting for I

1

,I

2

from (2.17, 2.18) into (2.49) and simplifying, we find

σ

E

=

q

σ

2

xx

+

σ

2

yy

+

σ

2

zz

−

σ

xx

σ

yy

−

σ

yy

σ

zz

−

σ

zz

σ

xx

+ 3

σ

2

xy

+ 3

σ

2

yz

+ 3

σ

2

zx

. (2.54)

For the special case of plane stress (

σ

zx

=

σ

zy

=

σ

zz

=0), this reduces to

σ

E

=

q

σ

2

xx

+

σ

2

yy

−

σ

xx

σ

yy

+ 3

σ

2

xy

. (2.55)

Finally, if

σ

yy

is also zero — i.e. there is only one tensile stress

σ

xx

and one shear

stress

σ

xy

acting on the same plane — we have the simple expression

σ

E

=

q

σ

2

xx

+ 3

σ

2

xy

. (2.56)

This situation occurs quite frequently — for example, when we have a bar sub-

jected to combined bending and torsion. Design handbooks (and many experienced

designers) tend to quote and use equation (2.56) without mentioning that it is a spe-

cial case of (2.54).

Example 2. 3

A cylindrical steel shaft of diameter 30 mm is subjected to a compressive axial force

F =10 kN, a bending moment M = 170 Nm and a torque T = 220 Nm. Estimate the

50 2 Material Behaviour and Failure

factor of safety against yielding using von Mises’ theory, if the steel has a yield stress

S

Y

=300 MPa.

The area A, second moment of area I, and polar moment of area J for the shaft

are

A =

π

×30

2

4

= 707 mm

2

; I =

π

×30

4

64

= 39.8 ×10

3

mm

4

;

J =

π

×30

4

32

= 79.5 ×10

3

mm

4

.

The axial force produces a normal stress

σ

zz

= −

F

A

= −

10 ×10

3

707

= −14.1 N/mm

2

(MPa) ,

the bending moment produces a maximum normal stress

σ

zz

=

Mc

I

= ±

170 ×10

3

×15

39.8 ×10

3

= ±64.1 MPa ,

where c is the maximum distance from the neutral axis, and the torque produces a

maximum shear stress

σ

z

θ

=

T R

J

=

220 ×10

3

×15

79.5 ×10

3

= 41.5 MPa ,

where R is the radius of the shaft.

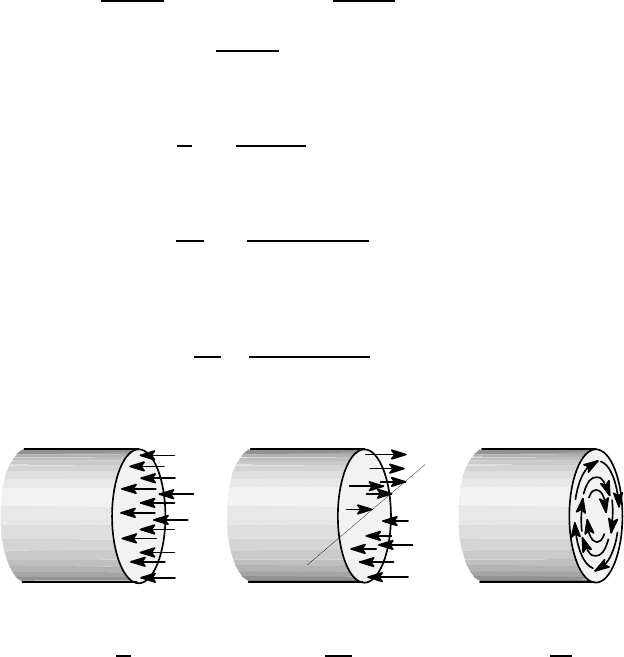

A

B

A

B

A

B

σ

zz

= −

F

A

σ

zz

=

My

I

σ

z

θ

=

Tr

J

(a) (b) (c)

Figure 2.13: Stress distributions due to (a) axial force, (b) bending and (c) torsion

The complete stress distributions due to axial force, bending moment and torque

are illustrated in Figure 2.13 (a,b,c) respectively. The most likely points for yielding

to occur are A and B, where the maximum bending stress and the maximum shear

stress due to torsion coincide. At A we have

σ

zz

= −14.1 + 64.1 = 50 MPa ;

σ

z

θ

= 41.5 MPa ,

whereas at B

2.2 Failure theories for isotropic materials 51

σ

zz

= −14.1 −64.1 = −78.2 MPa ;

σ

z

θ

= 41.5 MPa .

The equivalent tensile stress

σ

E

by von Mises’ theory is given by the polar coor-

dinate version of equation (2.54), which here reduces to

σ

E

=

q

σ

zz

2

+ 3

σ

2

z

θ

.

Clearly the maximum value will occur at B and is

σ

E

=

p

78.2

2

+ 3 ×41.5

2

= 106 MPa ,

so the safety factor against yield is

SF =

S

Y

σ

E

=

300

106

= 2.83 .

2.2.4 Brittle fa ilure

We now turn our attention to the failure of brittle materials by catastrophic frac-

ture. Look around you at some common objects. Those that can be caused to change

their shape permanently by the application of a sufficiently large load are ductile,

whereas those that will always return to their original shape on unloading until the

load reaches a value sufficient for catastrophic failure are brittle. Typical brittle mate-

rials are ceramics, glass and most kinds of rock. Metals are usually ductile, but some

can be made relatively brittle by appropriate heat treatment and most become brittle

at extremely low temperatures.

Brittle failure typically occurs by the propagation of cracks in the material. Most

materials contain a random array of microscopic defects such as cracks, voids, inclu-

sions of foreign materials, grain boundaries etc. and these serve as stress concentra-

tions when loads are applied to the body. When the material is ductile, the result is

some local plastic deformation that establishes a more favourable local microstruc-

ture and relieves the stress. Plastic deformation also causes some of the work done

by the applied loads to be dissipated as heat. By contrast, if the material is brittle, all

the work done is stored as elastic strain energy and is recoverable on unloading. In

many cases, crack growth is unstable once it starts because more energy is released

than is needed to sustain crack propagation, and the component fractures catastroph-

ically. The excess of strain energy converts to kinetic energy of the particles of the

body, so the body is left in a state of vibration, which is why fracture is noisy. Try (i)

bending a thin metal rod until it deforms plastically and (ii) breaking a similar glass

rod in bending and notice that the first process is silent, whereas the second is not.

Of course, you know this will be the case before you perform the experiment. It is

part of your experiential knowledge that we are trying to unlock.

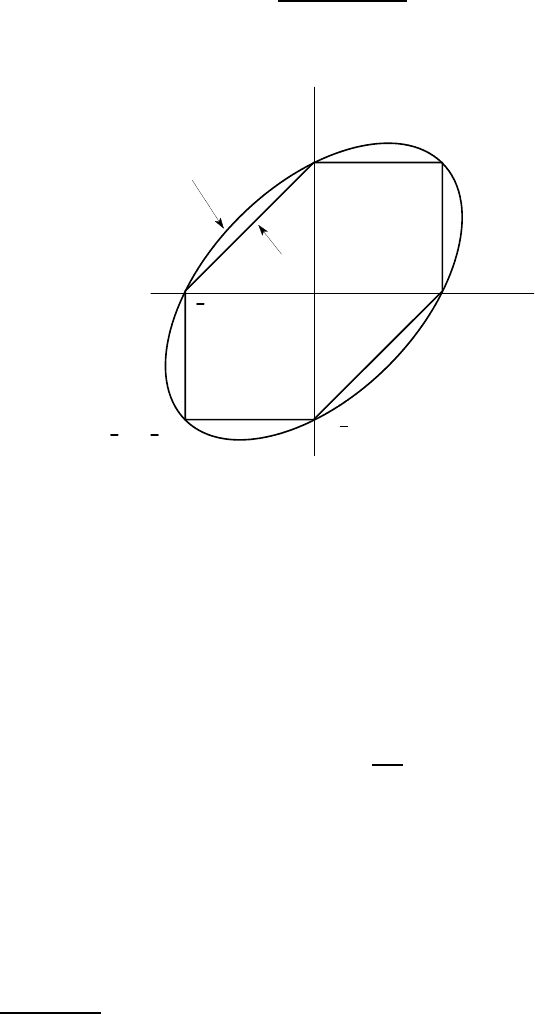

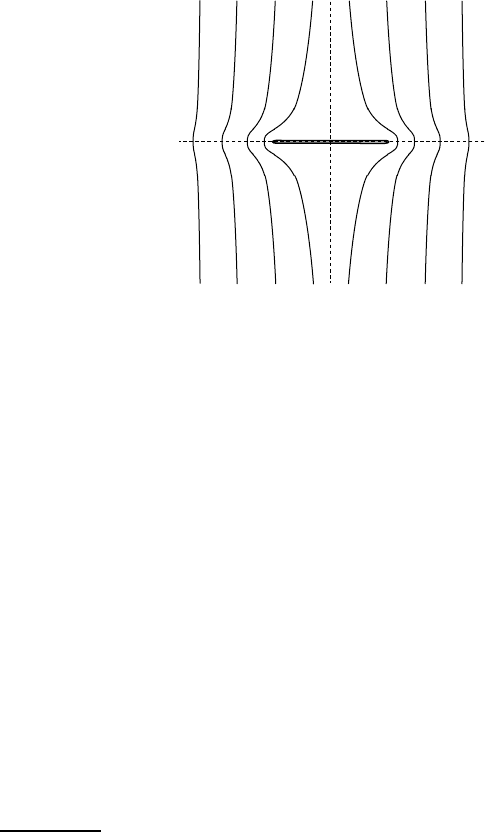

Stress intensity factor

The stress concentration due to a crack is caused by the fact that the crack is unable to

transmit tensile tractions, so the load has to be transmitted around the the crack tips,

52 2 Material Behaviour and Failure

as shown in Figure 2.14. Stresses are highest near the crack tips, where the load lines

are closest together. If the crack has zero thickness — i.e. the two faces just touch

when the body is unloaded — it can be shown that the theoretical elastic solution of

the problem involves stresses that tend to infinity with the inverse square root of the

distance from the crack tip.

20

Figure 2.14: Transmission of load around a crack

The simplest and most prevalent theory of brittle fracture — that due to Griffith

— states in essence that crack propagation will occur when the scalar multiplier on

this singular stress field exceeds a certain critical value. More precisely, Griffith pro-

posed the thesis that a crack would propagate when propagation caused a reduction

in the total energy of the system. Crack propagation causes a reduction in strain en-

ergy in the body, but also generates new surfaces which have surface energy. Surface

energy is related to the force known as surface tension in fluids and follows from

the fact that to cleave a solid body along a plane involves doing work against the

interatomic forces across the plane. When this criterion is applied to the stress field

in particular cases, it turns out that for a small change in crack length, propagation is

predicted when the multiplier on the singular term, known as the stress intensity fac-

tor, exceeds a certain critical value, which is a constant for the material known as the

fracture toughness. This is the central thesis of Linear Elastic Fracture Mechanics

(LEFM).

Stress intensity factors are conveniently defined in terms of the stress components

on the crack plane. If the crack is taken to occupy the region x< 0 on the plane y=0,

as shown in Figure 2.15, there are three possible stress components on the rest of

the plane (x > 0,y = 0), comprising a tensile stress

σ

yy

, an in-plane shear stress

σ

yx

and an out-of-plane (or antiplane) shear stress

σ

yz

. Unless they are zero, they will all

tend to infinity with x

−1/2

and we can define

21

stress intensity factors K

I

,K

II

,K

III

as

20

See, for example, J.R. Barber (2010), Elasticity, Springer, Dordrecht, 3rd edn., §11.2.3.

21

Notice that the factor (2

π

) in these definitions is conventional, but essentially arbitrary.

In applying fracture mechanics arguments, it is important to make sure that the results

used for the stress intensity factors (a theoretical or numerical calculation) and the fracture

toughness (from experimental data) are based on the same definition of K.

2.2 Failure theories for isotropic materials 53

O

x

y

Figure 2.15 Coordinate system for the semi-infinite crack

K

I

= lim

x→0

(2

π

x)

1

2

σ

yy

; K

II

= lim

x→0

(2

π

x)

1

2

σ

yx

; K

III

= lim

x→0

(2

π

x)

1

2

σ

yz

. (2.57)

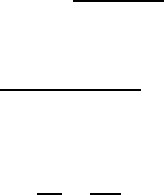

These are referred to as Mode I, II and III stress intensity factors respectively.

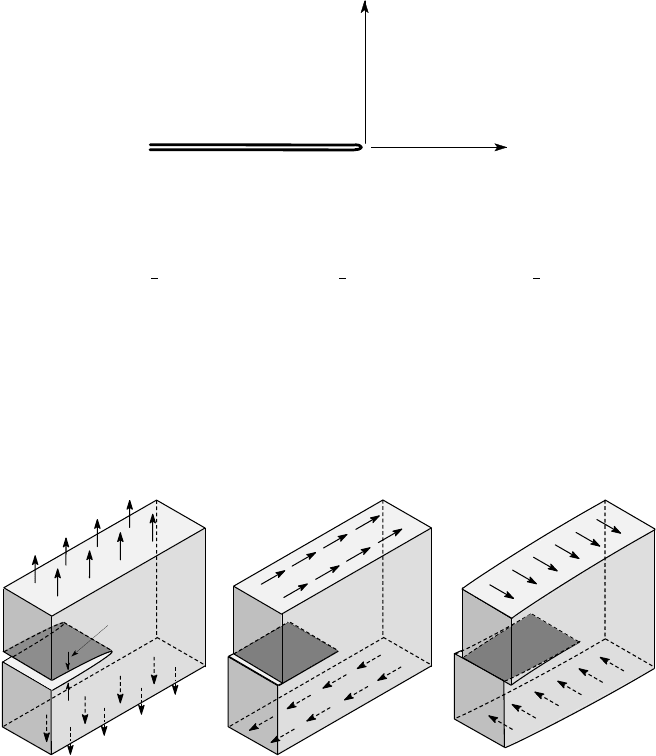

The deformations associated with the three modes are illustrated in Figure 2.16.

Notice how in mode I (opening mode) the crack faces are pulled apart giving rise to

a finite gap known as the crack opening displacement (COD). By contrast, the other

two modes involve tangential relative displacements at the crack faces, but there is

no crack opening displacement.

C.O.D.

Mode I Mode II Mode III

Figure 2.16: Loading of a cracked body in modes I,II,III

Reasons for the success of LEFM

It may seem paradoxical to found a theory of real material behaviour on properties

of a singular elastic field, which clearly cannot accurately represent conditions in the

precise region where the failure is actually to occur. After all, the theory of elasticity

is based on the assumption that the strains are small and this will clearly be violated

at sufficiently small distances r from the crack tip. Also, at very small r, we would

need to recognize that the material is not really a continuum, but has atomic struc-

ture and the crack cannot really be a geometric line with zero thickness, since if it

54 2 Material Behaviour and Failure

were, the interatomic forces would act across it and it would cease to be a crack.

However, if the material is brittle, the region in which the elastic solution is inappli-

cable may be restricted to a relatively small process zone surrounding the crack tip.

Furthermore, the certainly very complicated conditions in this process zone can only

be influenced by the surrounding elastic material and hence the conditions for failure

must be expressible in terms of the characteristics of the much simpler surrounding

elastic field. As long as the process zone is small compared with the other linear

dimensions of the body (notably the crack length), it will have only a very localized

effect on the surrounding elastic field, which will therefore be adequately character-

ized by the dominant singular term in the linear elastic solution, whose multiplier

(the stress intensity factor) then determines the conditions for crack propagation.

It is notable that this argument requires no assumption about or knowledge of

the actual mechanism of failure in the process zone and, by the same token, the

success of linear elastic fracture mechanics as a predictor of the strength of brittle

components provides no evidence for or against any particular failure theory.

22

Design based on fracture mechanics

Fracture mechanics methods enable us to predict the load at which a crack in a com-

ponent will start to propagate. The procedure is to calculate the stress intensity factor

at the crack tip and compare it with measured and tabulated values of fracture tough-

ness for the material. In most cases, fracture is dominated by tensile loading and

hence by the mode I stress intensity factor K

I

. The fracture toughness is therefore

defined as the value of K

I

at which fracture occurs and it is usually denoted by K

Ic

.

Fracture toughness is measured by loading a plane edge crack in a configuration

locally similar to that shown in Figure 2.15 (Mode I) above. The results obtained are

independent of the thickness of the specimen if this is sufficiently large, but tests on

thin specimens generally give larger values for fracture toughness because the free

surfaces of the specimen have a stress relieving effect. Standardized test specimens

are therefore used to ensure consistency of the results.

23

The use of tabulated K

Ic

val-

ues in design will give good predictions for cracks in plates as long as the thickness

of the plate t satisfies the condition

t ≥ 2.5

K

Ic

S

Y

2

.

For thinner plates, the condition K

I

<K

Ic

is conservative and a more efficient design

may be possible using more advanced concepts from elastic-plastic fracture mechan-

ics.

24

22

Indeed, experimental values of fracture toughness are not compatible with theoretical pre-

dictions based on Griffith’s theory and estimates of surface energy. For more details of the

extensive development of the field of fracture mechanics, the reader is referred to the many

excellent texts on the subject, such as Kanninen and Popelar (1985), Leibowitz (1971).

23

See, for example, Boresi et al. (1993), Figure 15.2.

24

See, for example, S.T. Rolfe and J.M. Barsom (1977), Fracture and Fatigue Control in

Structures, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Chapter 19.