Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

544 5 The Araucanian Sphere

pi-ke-yin

y

points at a firm and constant intention; in addition to ‘to say’, pi- also has the

meaning ‘to want’.

18. <fey-eŋŋnkafem-nie-a-y n

y

iwiŋŋka yeŋŋn.

he-3.PL also act.thus-CN-F-3.ID 3P non.Indian 3.PL

<And they will be doing the same to their Huincas.

19. ka fem-ŋŋe-ˇci nie-l-fi-pe malon eŋŋn.

also act.thus-LS-AJ have-BN-3O-3.IM raid 3.PL

And thus may they keep them (those Huincas) under attack.

The suffix -l- is here interpreted as a benefactive, in spite of the rather negative

connotation. Alternatively, it may be an instance of a ‘more involved object’ marker, as

described by Smeets (1989: 377–9).

20. fey mew kin

y

e-w-n nie-a-yin

y

awka-n θθŋŋu>’”.

that OC one-V.RF-IF have-F-1.PL.ID revolt-IF thing

So united we shall have a war at hand.>’”

The reflexive suffix -(u)w- here takes the function of a verbaliser, as it often does. The

expression kin

y

e-w-

n is used adverbially ‘together’, ‘in unity’. For the interpretation of

awka-n

θ

ŋ

u compare malon

θ

ŋ

u in sentence 4.

5.2 The Allentiac language

A reasonable amount of documentation exists on the Huarpean languages Allentiac and

Millcayac. All of it is due to Luis de Valdivia, who also authored the first grammar

of the Araucanian language. Two samples of the original edition of Valdivia’s work

on Allentiac, containing a ‘doctrina’, a catechism with instructions for confession, a

grammar and a Spanish–Allentiac word list (1607) were preserved until the twentieth

century, one in Lima (subsequently lost) and one in the National Library at Madrid.

The work was re-edited by Medina in 1894 and discussed in Mitre (1909–1910, volume

I). Mitre expanded the vocabulary with an Allentiac–Spanish word list and altered the

original spelling in several respects, substituting the symbol j for Valdivia’s <x> on

the (unmotivated) assumption that the latter represented a velar fricative, rather than a

palatal sibilant.

42

Valdivia’s work on Millcayac grammar remained lost for a long time,

leading to doubt as to whether it had ever been published, until in 1938 a copy of it

was discovered in the University Library of Cuzco by M´arquez Miranda. He had it

photographed by the Cuzco photographer Chambi and published its contents (M´arquez

Miranda 1943). We will give an impression here of Allentiac.

42

The alternative use of the forms acasllahue and acaxllahue for ‘virgin’ in Valdivia’s Allentiac

catechism speaks in favour of a (palatal) sibilant interpretation for <x>. The alternation of x

and ch in the verbal morphophonemics points in the same direction.

5.2 The Allentiac language 545

The absence of explanation concerning the pronunciation of Valdivia’s symbols makes

it a hazardous task to reconstruct the Allentiac sound system. On the morphological and

syntactic level a fuller picture of the language may eventually be obtained by a thorough

analysis of the religious texts that accompany the grammar (a first attempt is Bixio

1993). The Allentiac language apparently had a six-vowel system, similar to that in

Araucanian. Valdivia uses the symbol <`u> or <´u> for the sixth vowel, which may

have been an unrounded high back or central vowel, as in chal`u [ˇcal]

43

‘arrow’. It is

possible that Valdivia did not always write the sixth vowel, which could explain the

presence of occasional word-initial consonant clusters, e.g. in pxota [p()ˇsota] ‘girl’ and

qleu [k()lew] ‘on top of’. In one case both spellings are found: qtec and q`utec [k()tek]

‘fire’. To be noticed is the frequent occurrence of what was apparently a syllabic lateral,

as in lpu`u [l

˚

pu] ‘finger’. The language had a series of sibilants or assibilated affricates,

of which the exact value can only be guessed on the basis of the information given by

Valdivia. They are written <s>, <x>, <z> and <zh>, respectively. The symbol <s>

is limited in its distribution. It is found at the end of a syllable, usually before another

consonant (e.g. in taytayes-nen ‘I vanquish’), and in the word huss´u [hus] ‘ostrich’.

44

Examples of <x>, <z> and <zh> are xapi [ˇsapi] ‘death’, hueze [weze] ‘leg’ and zhuc˜na

[ˇzukn

y

a] ‘frog’. The interpretation of the symbols <z> and <zh> as voiced fricatives

([z], [ˇz]) is tentative and, in the case of <z>, partly based on the fact that there seems

to have been an opposition between <z> and <ss> in intervocalic position. In other

positions <z> may have had the value [s].

Allentiac is presented by Valdivia as an agglutinating, dominantly suffixing language.

It differs from Araucanian in having a well-developed set of case markers and post-

positions (e.g. -ta locative; -tati causal; -tayag beneficiary; -ye dative; -yen instrumental;

-ymen comitative). Person of possessor is indicated by adding the genitive case marker

-(e)ch or -(i)ch to the personal pronouns cu ‘I’, ca ‘you’ and ep ‘he/she/it’, viz. cu-ch ‘my’,

ca-ch ‘your’, ep-ech ‘his’. The same holds for the corresponding plural forms, which are

obtained by adding -cha to the personal pronouns, e.g. ep-cha ‘they’, ep-cha-ch ‘their’.

However, in pronouns associated with forms of the verbal paradigm the plural marker is

noted as -chu, rather than -cha (cu-chu, ca-chu, ep-chu). No inclusive–exclusive plural

43

Self-evidently, the phonetic transcriptions proposed in this paragraph are merely suggestive.

The combination gu can be interpreted as [w] before a, o, u; before i and e, the combination

hu serves that purpose. The symbol g alone and the combination gu before e and i may have

referred to a voiced velar stop, but more likely to a voiced velar fricative. The voiceless velar

stop [k] is written qu before e and i, q before silent `u or ´u, and c elsewhere. The symbols ch, ll

and ˜n were almost certainly as in Spanish.

44

The form huss´u (with final ´u)isexplicitly mentioned in Mitre (1909, I: 374), whereas Medina’s

edition has hussu.Weassume that in this case Mitre’s observation is correct because of his

having had direct access to the original edition, notwithstanding the fact that the word list in

Medina’s edition is a lot more trustworthy than Mitre’s.

546 5 The Araucanian Sphere

Table 5.4 Unmarked verbal paradigm in Allentiac

quillet- ‘to love’

1 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-nen ‘I love, want.’

plur. quillet-c-a-c-nen ‘We love, want.’

2 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-npen ‘You (sing.) love, want.’

plur. quillet-c-a-m-ne-c-pen ‘You (plur.) love, want.’

3 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-na ‘He/she loves, wants.’

plur. quillet-c-a-m-na ‘They love, want.’

distinction has been recorded. Plural of substantives is indicated by means of the element

guiam, e.g. in pia guiam ‘fathers’.

The verbal morphology of the Allentiac verb appears to be quite rich. Valdivia of-

fers an overview of the endings referring to person-of-subject, tense, mood, voice,

interrogation, nominalisation and subordination. There is also evidence of some deriva-

tional morphology which is not described systematically. The root of Valdivia’s model

verb quillet- ‘to love’, ‘to want’ is followed by a lexical extension -(e)c- in all of

its paradigms except for the future tense and its derivates. This extension is found

with a number of other verbs as well. Its function remains unexplained. The per-

sonal endings are preceded by a thematic vowel -a-,which can be left out as a re-

sult of morphophonemic adaptations (see below). In the endings the pluralising el-

ements -c- (for first and second person) and -m- (for second and third person) can

be recognised. The unmarked paradigm (present or preterit) of quillet-isshown in

table 5.4.

The same endings are found in the imperfect or habitual past, where an element -yalt-

is inserted after -(e)c-: quillet-ec-yalt-a-nen ‘I used to love, want’. Future is indicated by

the element -ep-(-ep-m- for the plain future), with elimination of the -(e)c- extension:

quillet-ep-m-a-nen ‘I shall love, want’. Verb roots which do not have the -(e)c- extension

in their paradigms may be subject to morphophonemic adaptations, such as the loss of the

thematic vowel a and other modifications, e.g. pacax-nen ‘I remove’, but pacach-a-npen

‘you remove’.

The endings of the imperative and interrogative paradigms differ considerably from

their affirmative counterparts. An example of the unmarked tense of the interrogative is

given in table 5.5.

Negation is indicated by means of a free element naha,

45

as in naha quillet-c-a-nen

‘I don’t want’, but for the imperative there are special negative markers, as can be seen

45

The negative marker naha is sometimes found as a prefix or proclitic na-, for instance, in

na-cu-ymen ‘without me’ (cu ‘I’, -ymen ‘with’).

5.2 The Allentiac language 547

Table 5.5 Interrogative verbal paradigm in Allentiac

quillet-

1 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-lte ‘Do I love, want?’

plur. quillet-c-a-c-lte ‘Do we love, want?’

2 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-n ‘Do you (sing.) love, want?’

plur. quillet-c-a-m-ne ‘Do you (plur.) love, want?’

3 pers. sing. quillet-c-a-nte ‘Does he/she love, want?’

plur. quillet-c-a-m-te ‘Do they love, want?’

in (107) and (108):

(107) quillet-ec-gua, quillet-ec-xec

love-VE-2S.IM

‘Love!’

(108) quillet-ec uche

love-VE 2S.IM.NE

‘Don’t love!’

In some parts of the verbal paradigm only number, not person, is morphologically

distinguished, as in the subordinative form called gerundio de ablativo by Valdivia

(109):

(109) quillet-ec-ma-ntista

love-VE-SU-SU

‘When I/you/he/she wants ...’

quillet-ec-ma-m-nista

love-VE-SU-PL-SU

‘When we/you (plural)/they want ...’

Active participles are formed by adding the elements yag ‘this’ or an-tichan to the

verb stem, passive participles by adding el-tichan. According to Valdivia, the el-tichan

nominalisation can serve as the basis for a passive construction in combination with the

verb m(a)- ‘to be’, but he also mentions an alternative construction consisting of the

active form preceded by the element quemmec.

(110) quillet-ec el-tichan m-a-npen

love-VE PS-N be-TV-2S

‘You are loved.’

548 5 The Araucanian Sphere

(111) quemmec quillet-c-a-npen

PS love-VE-TV-2S

‘You are loved.’

The verbal transitions (object marking) are indicated by means of special pronominal

elements which precede the verb root and which are inserted between the pronominal

subject (if any) and the verb root itself. The first-person singular object marker is either

cu-ye (pronoun ‘I’ + dative case), or in a contracted form que; its plural counterpart

is either quex, xque,orcuchanen. The second-person-singular object marker is ca-ye

(pronoun ‘you’ + dative case); its plural counterpart is either cax, xca or xcaummi. The

third-person object marker is pu or p`u for the singular, and either pux or p`ux,orxpu or

xp`u for the plural. In the transition 1S-2O the object marker can either precede the verb,

or be infixed, so that we have the following alternatives:

(112) cu ca-ye quillet-c-a-nen

Iyou-DA love-VE-TV-1S

‘I love you (singular).’

(113) quillet-ec-ca-nen

love-VE-2O-1S

‘I love you (singular).’

The transition 2S-1O can be expressed in two ways, either as described above, or by

special endings:

(114) ca-chu que quillet-c-a-m-ne-c-pen

you-PL 1.SG.DA love-VE-TV-PL-2S-PL-2S

‘You (plural) love me.’

(115) ca-chu quillet-ec-quete

you-PL love-VE-2S.PL.1O.SG

‘You (plural) love me.’

Reflexivity is indicated by means of the root ychacat [iˇcakat] ‘self’, which can be

used with a pronoun, as in cu ychacat ‘I myself’. Alternatively, it can be infixed in the

verb (before the extension, if any).

(116) Pedro quillet-ychacat-c-a-na

Pedro love-RF-VE-TV-3S

‘Pedro loves himself.’

Valdivia’s Allentiac lexicon contains very few terms referring to nature and envi-

ronment. Mitre (1909, I: 349) attributes this to the fact that Valdivia’s consultants were

emigrated Huarpeans who had preferred the relative security of Spanish rule in Chile

5.2 The Allentiac language 549

to their original habitat, surrounded as it was by warlike neighbours. The language has

a decimal system of numerals: lcaa ‘one’, yemen ‘two’, ltun ‘three’, tut ‘four’, horoc

‘five’, zhillca ‘six’, tucum ‘ten’; the numbers for ‘seven’, ‘eight’ and ‘nine’ are com-

pounds, respectively, yemen-qlu, ltun-qleu, tut-qleu. The word for ‘hundred’ is pataka,

a loan from Aymara or Mapuche. Interesting is the shape of colour terms; they all con-

sist of a reduplicated element followed by the ending -niag: hom=hom-niag ‘black’,

zas=zas-niag ‘red’.

Valdivia’s Allentiac lexicon contains a few loan words, such as, y˜naca ‘princess’

(Aymara in

y

aqa ‘young lady’), mita ‘time’, ‘turn’ (Quechua mit’a), mucha-pia-nen ‘I

kiss’ (Quechua muˇc’a- ‘to kiss’) and quillca-tau-nen ‘I write’ (Quechua qil

y

qa- ‘to

write’). The functions of the elements -pia- and -tau-inthe last two examples are not

known; they may reflect either cases of derivation, or compounds containing the roots

pia ‘father’ (or another element yet to be identified) and tau- ‘to put’. Interesting cases

are the word for ‘house’ ut(u), reminiscent of Aymaran uta, and the word for ‘bread’

kupi. Mitre (1909, I: 382) affirms that this is an arbitrary, transcultural translation of

Valdivia, because kupi referred to a staple food of the Huarpeans, the dried roots of

reed-plants from the lakes. The resemblance with Mapuche kofke ‘bread’ is noteworthy.

6

The languages of Tierra del Fuego

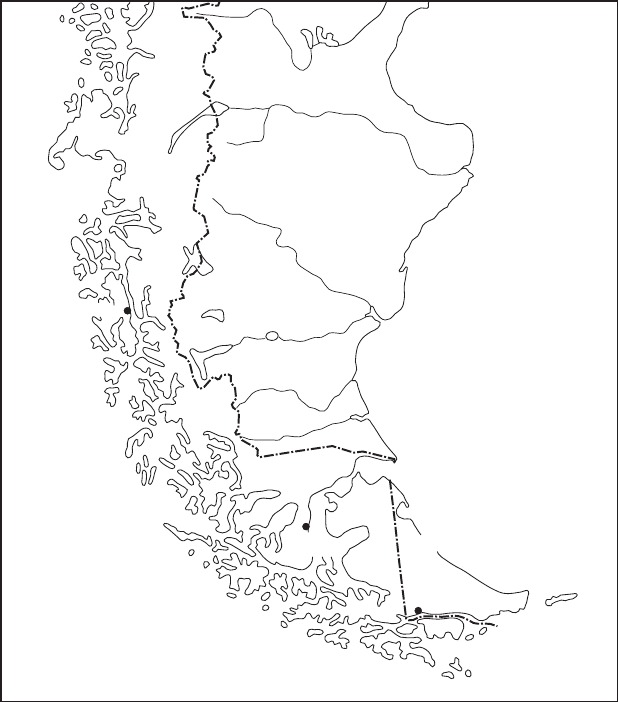

On Tierra del Fuego, the archipelagos surrounding it and the neighbouring mainland,

Patagonia, nine indigenous languages were spoken, of which only a few have survived

to the present day. With respect to the peoples of Tierra del Fuego, a distinction is made

traditionally between the canoe nomads, including the Chono, the Kawesqar and the

Yahgan, and the foot nomads, including the Haush and the Selk

nam. In the latter group

the G¨un¨una K¨une, the Tehuelche and the Tehues or Teushen are also included (Clairis

1985).

As Guyot (1968) notes, the area of Tierra del Fuego had already been visited by eighty-

one exploratory expeditions by the time the HMS Beagle, carrying Charles Darwin,

passed through the area. Different visitors projected different images onto the nomadic

groups they encountered. Thus Darwin writes: ‘The language of these people, according

to our notions, scarcely deserves to be called articulate’ ([1906] 1983: 195). The Fuegians

could be seen as a decidedly lower step in human development, in his perception.

It was against this view that Thomas Bridges, a missionary in the area from 1869

to 1887 on behalf of the South American Missionary Society, argued with his mas-

sive 30,000-word Yahgan–English dictionary. On the basis of it he is quoted by Guyot

(1968) as having written in an Argentinian newspaper that ‘Incredible though it may

seem, the language of one of the poorest tribes, without literature, nor poetry, nor

songs, nor science, has nonetheless, owing to its structure and its functions, a list of

words which surpasses that of tribes much more evolved with respect to their art and

the satisfaction of their needs’ (translated from French in Guyot 1968: 8). The large

speculative and impressionistic literature on these groups has not automatically led to

very thorough descriptions and profound analyses, however. Here we try to give a sketch

of some of the linguistic properties of the languages involved, building on the recent

careful historical, descriptive and comparative work of scholars such as Casamiquela,

Clairis, Fern´andez Garay and Najlis, and on the monumental earlier studies of Bridges,

Cooper and Gusinde, among others.

Cooper (1946a) tries to give a general description of the traditional cultures of Tierra

del Fuego, partly on the basis of accounts of travellers who came into contact with

6 The languages of Tierra del Fuego 551

SELK'NAM(†)

HAUSH(†)

TEHUELCHE

Punta

Arenas

Ushuaia

ARGENTINA

TEUSHEN(†)

Puerto Edén

C

h

i

c

o

R

.

C

H

I

L

E

TEHUELCHE

YAHGAN

K

A

W

E

S

Q

A

R

C

H

O

N

O

(

†

)

Map 13 The languages of Tierra del Fuego

these generally nomadic groups. The people living at this end-point of the world had

gathering economies; cultivated plants were only found in the north, at the margins of the

Araucanian Sphere. Their only domestic animals were the dog and – for some groups –

the horse. Dogs were for some groups only adopted in the colonial period, and horses

came in during the eighteenth century. They had moveable shelters, and no raised beds

or hammocks. Their weapons were made of stone, wood or bone. Metal weapons and

tools were introduced after contacts with Europeans. The canoe nomads lived mainly

on seals, fish and shellfish; the pedestrian nomads hunted land animals such as the

guanaco (a relative of the llama) and the rhea (an ostrich-like creature). On the Atlantic

552 6 The languages of Tierra del Fuego

side the emphasis was on land hunting, while on the Pacific side the early inhabitants

lived from fishing and sea hunting, supplemented by shellfish gathering and hunting of

sea birds (Rivera 1999: 754). The area shows 6,000 years of continuous occupation,

made possible by low population density and enormous maritime resources (Rivera

1999: 756).

The people lived in well-organised families and monogamy was prevalent. Social

organisation was in terms of bands, without clearly distinct chiefs, corresponding perhaps

to extended families. Land-tenure was organised along the lines of the family hunting-

ground system. When food was becoming scarce in one place, the family or band would

move on to a different area and settle temporarily. There is no evidence of cannibalism,

and people held theistic or shamanistic beliefs.

We will now turn to a brief description of the distribution of the different language

groups in the area.

6.1 The languages and their distribution

A schematic representation of the traditional areas of the Fuegian languages is given on

the map at the beginning of this chapter. Turning counter-clockwise along the coast of

Chile, the northernmost group is the Chono or Aksan´as (the Kawesqar word for ‘man’),

now extinct, who lived in the area from the Corcovado Gulf, south of Chilo´e, to the

Gulf of Pe˜nas. Cooper (1917) has carefully summarised all that can be gathered from

accounts of the Chono, from Jesuit missionaries in 1612 to an English ship captain in

1875. Canoe nomads, they had adopted a few Araucanian elements (Cooper 1946b):

sporadic gardening (e.g. potatoes) and herding, the polished stone ax and the plank

boat (dalca). Below we will briefly present the available data about possible numbers of

Chono speakers.

Cooper (1917) concludes from a survey of the ways the language of the Chono is

described in the sources, including accounts of interpreting etc., that Chono was cer-

tainly distinct from Mapuche and Tehuelche, and more probably than not also from

Kawesqar. An independent Chono group figured already in Chamberlain’s classification

of 1913. Clairis (1985) bristles at the idea of speaking of a language that we know al-

most nothing about, except for some ethnohistorical accounts. Here we will be more

audacious and try to sift through the information there is, particularly the eighteenth-

century catechism found in Rome archives and published by Bausani (1975), with a

tentative interpretation. A similar attempt has been undertaken by Viegas Barros (to

appear a). In table 6.1 we give the correspondences between lexical elements tenta-

tively identified by Bausani and their equivalents in the data presented by Skottsberg

(1913) and Clairis (1985). Skottsberg claimed to have discovered a group of ‘West

Patagonian Canoe Indians’ distinct from the Kawesqar and presumably identical to

the Chono. The word lists presented suggest that this is not the case, however. On

6.1 The languages and their distribution 553

Table 6.1 The relation between putative Chono words identified by Bausani (1975) and

their possible equivalents in the Alacalufan materials of Skottsberg (1913) and Clairis

(1987) (supplemented by Viegas Barros 1990)

Bausani

*

Skottsberg Clairis

sky acha arrx

h

acaqsta ‘warm, good weather’

ac’ayes ‘sun’

father sap ˇc´ıˇca:r cecar

man yema ´akˇseˇs aqsenes, aqsanas yema ‘white man,

Chilean’

three tas t´aw-kl(k) tow, taw ‘other’, wokst´ow

uklk-at-tawɹlk ‘three’ (Aguilera 1978)

good lam l´a:yip layep, layeq

yes jo ´aylo ayaw

believe [credere] jo-cau kstiˇs

y

‘speak’ afsaq

h

as ‘speak’

son cot ´ık

y

awt ‘baby’ eyx

y

ol ‘son’

one ¨ue˜nec t´akso taqso

d´akuduk

no yamchiu t´axli, k

y

ip q

y

ep, q

y

eloq

*

The Bausani spellings are the original ones.

the whole the words given by Skottsberg correspond to those presented by Clairis.

Only rarely do the words given by Bausani correspond directly with those provided by

Clairis and Skottsberg, although Viegas Barros (to appear a) argues that 45 per cent

of the Chono lexical and grammatical elements resemble those of Kawesqar and/or

Yahgan.

The Kawesqar (also referred to as Qawasqar) or Alacaluf traditionally occupied the

territory from the Gulf of Pe˜nas to the islands west of Tierra del Fuego, and lived

mostly from fishing, like the Chono. Bird (1946) estimates that there may have been

maximally a few thousand Kawesqar at the time of first contact; according to Clairis

(1985) there were forty-seven Kawesqar left in 1972, living on the bay of Puerto Eden

on the east coast of Wellington Island. The 1984 census gives twenty-eight speak-

ers. There was some original confusion about this language. Clairis (1985) criticised

Loukotka for distinguishing two linguistic isolates among the sea nomads who in-

habited the southern Chilean archipelago between Chilo´e and Tierra del Fuego. Fol-

lowing Hammerly Dupuy (1947), Loukotka recognised a separate group, Aksan´as or

Kaueskar, that would have been different from Alacaluf. Clairis observes that Qawasqar

(Kaueskar) is the autodenomination of the Alacaluf, whereas Aksan´as means ‘man

(male)’ in their language. It appears from the listing of languages included in Loukotka’s

Aksan´as group that he attributed some of the ethnonyms referring to the Alacaluf to the