Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

514 5 The Araucanian Sphere

It should be observed that in many other varieties of Mapuche, the sequence *

y

(∼iy)isrealised as i (e.g. kon-i ‘he entered’, kim-i ‘he knows’), a state of affairs which

suggests that the consonantal status of y in those varieties may be less pronounced (see,

for instance, D´ıaz-Fern´andez 1992; Augusta 1903, 1916). On the other hand, Augusta

does register the word we

n

y (written wen·¨ui) for ‘friend’.

The status of w can best be illustrated with verbs containing the reflexive suffix

-(u)w-; they are clearly different in pronunciation from their counterparts without that

suffix.

(7) elu-w-a-n elu-a-n

give-RF-F-1.SG.ID give-F-1.SG.ID

‘I shall give to myself.’ ‘I shall give (to someone).’

(Smeets 1989: 31)

(8) elu-w-ke-n elu-ke-n

give-RF-CU-1.SG.ID give-CU-1.SG.ID

‘I usually give to myself.’ ‘I usually give (to someone).’

10

(Smeets 1989: 31)

The Mapuche consonant inventory is characterised by a rather extensive array of

articulatory positions. Valdivia (1606) already observed the existence of a phonemic

opposition between interdental [

l

ˆ

,

n] and alveolar [l, n] resonants. He used the symbols

<

´

l> and <´n>, respectively, to represent the interdental sounds. However, Valdivia did

not recognise the interdental stop [

t

ˆ

], which is also recorded in Mapuche, reserving his

symbol <

¯

t> for the retroflex stop (see below).

At present, the different local varieties of Mapuche, both on the Chilean and on the

Argentinian side, have either preserved or lost the distinction between interdental and

alveolar consonants. For instance, in Argentina the Ranquelino dialect of northwest-

ern La Pampa lacks the distinction (Fern´andez Garay 1991), whereas the dialect of

Rucachoroy in Neuqu´en (Golbert de Goodbar 1975) preserves it. In Chile, the Huil-

liche (cesu

ŋ

un)variety of San Juan de la Costa (Osorno) no longer preserves the

distinction in the nasal and the stop series, but has developed a distinctive retroflex

l

.

in addition to a plain l and a ‘postdental’ (interdental)

l

ˆ

(Alvarez-Santullano Busch

1992).

11

10

A parallel case with y is leli-e-n ‘you watched me’ versus leli-ye-n ‘I watched many things’

(Smeets 1989: 30).

11

Alvarez-Santullano Busch provides no examples of the ‘postdental’

l

ˆ

. The examples given by

her and by Salas (1992a: 87) suggest a historical correlation between the interdental

l

ˆ

of central

Mapuche and the retroflex l

.

of Huilliche. The matter needs further investigation.

5.1 Araucanian or Mapuche 515

The continued existence of the interdental–alveolar distinction in the Chilean

Mapuche heartland has been the object of conflicting observations. Salas (1992b:

502–3) insists that the distinction is fully in use. He refers to the work of Lenz (1895–7),

Echeverr´ıa Weasson (1964) and Lagos Altamirano (1981), who confirm this, and states

that three different groups of native language planners and educators have considered

it necessary to include the distinction in the orthography.

12

On the other hand, Croese

(1980: 14), in his Mapuche dialect survey, affirms that the distinction is practically lost,

and that he found no awareness among the natives of its possible relevance. This is con-

firmed by Smeets (1989: 34–6). She gave the matter special attention but was forced to

conclude that her consultants, all fluent speakers of the language, did not make the dis-

tinction.

13

As it appears now, the preservation of the interdental–alveolar distinction in

Mapuche must be related to the individual or family level, rather than to geographically

based dialects.

An additional problem concerning the interdental–alveolar distinction in Mapuche is

the inconsistency of the observations. Lexical items, such as

l

ˆ

afke

n

ˆ

‘sea’,

n

ˆ

amu

n

ˆ

‘foot’

and m

t

ˆ

a ‘horn’, are usually among those recorded with interdental consonants, but in

other cases there is no such consistency. For instance, Salas (1992a) writes

t

ˆ

¨ufa ‘this’,

a

n

ˆ

t

ˆ

¨u ‘day’ and k¨ule

n

ˆ

‘tail’, where Augusta (1916) has t

ə

fa, ant¨u and k

ə

len, respectively.

Given the frequency of occurrence of at least the two first items, this is a remarkable

discrepancy.

14

In addition to the alveolar and interdental nasals, all Mapuche dialects distinguish

at least three more nasals: bilabial m, palatal n

y

and velar

ŋ

.

15

The interesting feature

of the Mapuche nasals is not their number, which more or less follows the selection

of obstruent articulations, but rather the fact that, within the limitations of Mapuche

word structure, they can occur in almost any position and combination. Nasal clusters

are frequent even within morphemes. The low level of nasal assimilation (none at all

at morpheme boundaries) is remarkable. The following examples illustrate some of the

12

These groups are the committee responsible for the development of the Alfabeto mapuche

unificado (Unified Mapuche Alphabet), the members of an alphabetisation workshop organised

by the Catholic University of Temuco, and the native authors participating in the workshops of

the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

13

The late Luis Quinchavil Su´arez from Nueva Imperial, the principal Mapuche consultant of the

Leiden project underlying Smeets’s dissertation of 1989, was aware of the interdental–alveolar

distinction among elder Mapuche speakers but did not make the distinction himself.

14

When Mapuche speakers abandon the alveolar–interdental distinction, it does not mean that the

interdental articulation as such is lost. The overall make-up of the Mapuche sound system favours

interdental, rather than alveolar pronunciation. This may explain why present-day observers tend

to record more interdentals than those historically attested.

15

The usual transcription of the n

y

and the

ŋ

is ˜n and ng, respectively. For the latter sound, Valdivia

used the symbol <¯g>.

516 5 The Araucanian Sphere

positions that nasals can take.

16

(9) lamŋŋen

‘sister’, ‘brother of a woman’

(10) man

y

ke

‘condor’

(11) man-kuw-l-n

right-hand-T-IF

‘to give one’s right hand to someone’

(12) aku-n

y

ma-n weˇsa θθŋŋu

arrive-DM-1.SG.ID bad word

‘I got some bad news.’

(Augusta 1966: xiii)

(13) wel

y

-w

n-ŋŋe-n

imperfect-mouth-CV-IF

‘to have an imperfect beak (of a parrot)’

(Augusta 1966: 265)

The fricative series of seventeenth-century Araucanian was remarkable not so much

for what it included, but more so for what it lacked. Valdivia (1606) is very explicit in

his statement that the language had no <¸c> [s], no <x> [ˇs], no <j> [h ∼ x] and no <f>

[f], in the way Spaniards would pronounce them. Instead, there was a voiced interdental

fricative <d> [ð], a voiced bilabial or labiodental fricative, written <v> or <b> [v ∼

β], and a voiced retroflex fricative or glide reminiscent of the English ‘r’in‘to worry’,

which was written <r> [ɹ]. This, at least, is the picture that can be reconstructed by

referring to the situation in the different varieties of the language today.

In the modern dialects the voiced pronunciation of the labial and interdental fricatives

has been preserved in Ranquelino and in the northern (Picunche) half of the Arauca-

nian heartland (especially in Arauco, Biob´ıo and Malleco). In the southern half of the

Araucanian heartland and in the Huilliche area the voiceless fricatives [

θ] and [f] are

preferred over voiced [ð], [v], [β].

17

Fern ´andez Garay (1991) notes that the Argentinian

varieties of Neuqu´en and R´ıo Negro show variation with a preference for the voiceless

options.

Most contemporary varieties of Mapuche have introduced a voiceless alveodental

sibilant s,avoiceless alveopalatal sibilant ˇs,orboth. These sounds are found in borrowed

words and, at least in the Temuco area, in forms that are somehow sound-symbolically

16

With the exception of material taken from Valdivia, all examples borrowed from the literature

will henceforth be transposed into the current notation system of this book. Given the controversy

on the interdentals, these will be indicated even when the original source does not distinguish

them from the alveolars.

17

In the word muðay ‘chicha (an alcoholic drink)’ voiced [ð]isfound, even with speakers who

normally use the voiceless realisation ([

θ]).

5.1 Araucanian or Mapuche 517

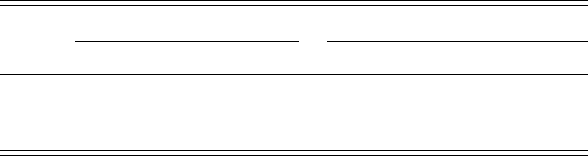

Table 5.1 Mapuche consonant inventory

Labial Interdental Alveolar Retroflex Palatal Velar

Obstruents p

t

ˆ

tˇc

.

ˇck

Fricatives f

θ (s) r [ɹ](ˇs)

Laterals

l

ˆ

ll

y

Nasals m

n

ˆ

nn

y

ŋ

Glides w y (γ )

related to words containing r or

θ

, e.g. kure ‘wife’, kuˇse, kuse ‘old woman’, ku

θ

e ‘old

woman (despective)’; cf. Smeets (1989: 38). In several old loan words the Spanish plural

marker -s has been replaced by Mapuche -r (e.g. awar ‘beans’ from Spanish habas), a

fact which illustrates the difficulty that seventeenth century Araucanian speakers must

have experienced when trying to pronounce the Spanish s. The velar voiceless fricative

is still absent from the present-day Mapuche varieties. Its Spanish representative has

been replaced by a stop k in some loan words (e.g. keka-w- ‘to complain’ from Spanish

quejarse; Smeets 1989: 69).

In Huilliche, the modern reflex of the r sound is a retroflex sibilant, as in kuˇs

.

am ‘egg’,

Mapuche kuram.Aglottal or velar voiceless fricative [h ∼ x] is optionally found as a

variant of f,asinkohke ‘bread’, Mapuche kofke; and xoˇs

.

u ‘bone’, Mapuche foro (Salas

1992a: 87–8).

The stops and affricates of Mapuche have the characteristic in common that they can

only occur syllable-initially. The labial and velar stops p and k appear in non-productive

morphophonologically related verb-pairs such as af- ‘to end’ (intransitive), ap-

m- ‘to

end’ (transitive), and naγ- ‘to descend’ (intransitive), nak-

m- ‘to take down’ (transitive),

which indicate an extinct process of fricativisation in root-final position. There are two

affricates, palatal ˇc and retroflex ˇc

.

(traditionally written ch and tr, respectively). The

retroflex varies between an affricate and a stop. Valdivia’s representation of this sound

by means of the symbol <

¯

t> indicates that the stop realisation may have been the only

one possible in the seventeenth-century Santiago dialect.

In summary, the original Mapuche consonant inventory is represented in table 5.1.

Borrowed sounds and sounds of debatable phonemic status are given between brackets.

The obsolescent character of the interdentals is not taken into account. The classification

of the resonant r as a fricative is motivated by its interrelations with the other fricatives.

5.1.3 Grammar

The overall structure of the Mapuche language resembles that of the central Andean

languages Aymara and Quechua as far as the complexity and the transparency of the

morphology, as well as the dependency on suffixes, are concerned. Nevertheless, there

518 5 The Araucanian Sphere

are some notable differences. Whereas the verbal morphology is exceptionally rich,

including, for example, a productive system of noun incorporation, nominal morphology

is weakly developed.

Although noun incorporation is a frequent phenomenon in the New World, it is

relatively rare in the Andean area. Araucanian noun incorporation drew the attention of

Valdivia (1606), who recorded some very illustrative examples of object incorporation

in the seventeenth-century language, permitting us to observe the difference between an

incorporated and a non-incorporated construction. (The examples are given here in the

original spelling and their phonetic interpretation between square brackets.)

(14) qui ˜ne huinca mo are-tu-bi-n ta ˜ni huayqui

[kin

y

ewiŋka mo are-tu-βi-n ta n

y

iwayki]

one foreigner OC lend-LS-3O-1.SG.ID FO 1P.SG lance

‘I lent my lance to a Spaniard.’

(Valdivia 1606: 40)

(15) are-huayqui-bi-n ta qui˜ne huinca

[are-wayki-βi-n ta kin

y

ewiŋka]

lend-lance-3O-1.SG.ID FO one foreigner

‘I lent my lance to a Spaniard.’

(Valdivia 1606: 40)

Although the two sentences are translated in the same way, Valdivia points out the

syntactic consequences of using either construction. In (14) the noun phrase referring

to the recipient contains the postposition mo (also mu or mew in modern Mapuche),

which indicates an oblique case. The third-person object marker -ßi- corefers to ‘my

lance’, which is the direct object. In (15) the noun referring to the lance is incorporated

in the verb form. The object marker -ßi- corefers to the next object available, which is

the recipient in this case. Valdivia describes the incorporated variant as ‘an elegant way

of speaking’ (elegante modo de hablar).

18

In the present-day language noun incorporation is still fully in use (cf. Harmelink

1992). In addition to object incorporation, theme subjects can be incorporated as well,

as in kuˇc

.

an-lo

ŋ

ko- ‘to have a headache’, from kuˇc

.

an- ‘to be ill’, ‘to be in pain’ and lo

ŋ

ko

‘head’. The incorporated noun always follows the verb root. In fact, Mapuche noun

incorporation must be analysed as part of a general tendency of the language towards

compounding, which again is more salient in the verb than in the noun (cf. Smeets 1989:

416–20). The possibilities of Mapuche verbal compounding are illustrated in example

(16), which contains a compound of two verb roots and an incorporated object associated

with the second verb root. The incorporated object iyal ‘food’ (from i- ‘to eat’, -a- ‘future

18

In modern Mapuche the form are-tu-(which includes a lexicalised suffix -tu-) means ‘to borrow’,

rather than ‘to lend’, for which the causative are-l-isnow preferred. The root are-nolonger

occurs by itself. We can only conclude that in seventeenth-century Santiago Araucanian are-tu-

was used in the meaning ‘to lend’, whereas the root are-was reserved for incorporation.

5.1 Araucanian or Mapuche 519

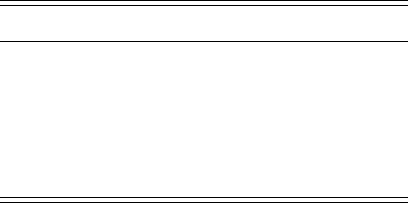

Table 5.2 Personal and possessive pronouns in Mapuche

Independent personal pronouns Possessive personal modifiers

Singular Dual Plural Singular Dual Plural

1 pers. in

y

ˇce

*

in

y

ˇciu in

y

ˇcin

y

n

y

iyu yin

y

2 pers. eymi eymu eym

nmi mu m

n

3 pers. fey fey-e

ŋ

ufey-e

ŋ

nn

y

in

y

i ...e

ŋ

un

y

i ...e

ŋ

n

*

In Mapuche studies, the nasal in the first-person pronouns is usually marked as palatal, but

the palatal element is, in fact, a case of assimilation of the nasal with the following affricate

(Smeets 1989: 129). The sources are not consistent in their treatment of this cluster; Augusta,

for instance, records i˜nche ‘I’ (1966: 73), but minche ‘below’ (1966: 150).

tense’, and -(e)l ‘non-subject nominaliser’) is itself a nominalised verb form containing

a tense marker.

(16) kim-

θθewma-iyal-la-y

19

know-make.ready-food-NE-3.ID

‘He does not know how to cook.’

The image of Araucanian as a language entirely depending on suffixation is nuanced

by the fact that it has a unique set of possessive modifiers, which play a crucial role

in the grammar. These possessive modifiers have no independent referential meaning

and can only occur before nouns and nominalised verbs. They must not be treated

as prefixes, however, because there is no phonetic coalescence, and because they can

be separated from the noun by another modifier, such as an adjective. The possessive

modifiers are formally related to the independent personal pronouns. The grammatical

distinctions expressed in the pronominal system are person (first, second, third) and

number (singular, dual, plural). Number of a third person is expressed by postposed clitic-

like elements (dual e

ŋ

u, plural e

ŋ

n), which can but need not merge with the preceding

noun or pronoun. Table 5.2 contains the inventory of personal pronouns and possessive

modifiers in Mapuche.

In a possessive construction the presence of a possessive personal modifier is oblig-

atory. When the possessive modifier is not preceded by a pronoun or another modifier,

an element ta- can be prefixed to it without a notable change in meaning, e.g. ta-n

y

i,

ta-mi, etc. The possessive personal modifier can be preceded by an independent personal

pronoun for emphasis or disambiguation (in the case of n

y

i,which is used both for first

person singular and for third person). The pronoun and the possessive modifier must

19

Sequences of vowel-final and vowel-initial stems in compounds may be separated by a pause or

a phonetic glottal stop, as is the case in (16).

520 5 The Araucanian Sphere

agree in person and, if not third person, also in number.

(17) mi ruka eymi mi ruka

2P.SG house you.SG 2P.SG house

‘your house’ ‘your house’

Number of third person is marked only once, either directly on the pronoun, or by

e

ŋ

u/e

ŋ

n following the head (Smeets 1989: 130).

(18) fey-eŋŋun

y

i ruka n

y

i ruka eŋŋu

he/she/it-D 3P house 3P house 3.D

‘the house of the two of them’ ‘the house of the two of them’

The genitive construction in Mapuche patterns in the same way as the possessive con-

structions containing a personal pronoun illustrated in (17) and (18), with the restriction

that the possessive modifier must be third person.

(19) tfa-ˇci wenˇc

.

un

y

i ruka

this-AJ man 3P house

‘this man’s house’

Whereas in possessive constructions the modifier precedes the modified, this may be

the other way round if the genitive relationship is not explicitly marked. Such construc-

tions usually have a part-of-whole interpretation, e.g. me yene ‘amber’, literally, ‘whale’s

dung’, from me ‘dung’ and yene ‘whale’ (Augusta 1966: 143). By contrast, noun phrases

in which the modifier precedes the modified, e.g. p

ron f

w ‘knotted thread’, ‘quipu’ (cf.

chapter 3), or awkan

θ

u

ŋ

u ‘war matter’ (see the text in section 5.1.5), are more common.

Real compounds, such as mapu-ˇce also have the latter order of constituents.

Mapuche has only one true case marker, the postposition mew (also mo, mu), which

indicates oblique or circumstantial case. Its uses are so manifold that it is difficult to

reduce them to a single semantic definition. It can refer to any non-specific location

(‘at’, ‘to’, ‘from’), time (‘since’, ‘after’, ‘during’), instrument or means (‘with’, ‘by’),

cause (‘because of’), circumstance (‘in’), as well as the standard of a comparison (cf.

Harmelink 1987; Smeets 1989: 76–83). It can also indicate an indirect object; see (14).

More specific spatial relations can be expressed either by means of adverbs indicating

the position of a referent (20), or by means of verbs which encode such relations in their

lexical meaning (21).

(20) inal-tu

l

ˆ

afke

n

shore-AV sea

‘at the seashore’

(Augusta 1991: 266)

5.1 Araucanian or Mapuche 521

(21) inal-kle-y

l

ˆ

ewf mew

be.at.the.edge-ST-3.ID river OC

‘It is at the banks of the river.’

(Augusta 1966: 72)

The Mapuche construction that expresses the concept of comitative does not involve

any case marker. Instead, the distinctions of person and number (dual and plural) per-

taining to the personal reference system are exploited. There is a special set of markers

exclusively for use in the comitative construction, in which those referring to first person

dual and plural are identical to the corresponding personal pronouns (in

y

ˇciu, in

y

ˇcin

y

); the

markers for second person dual and plural are emu and em

n, respectively, and those for

third person, e

ŋ

u and e

ŋ

n.

20

The comitative marker specifies the grammatical person of

the group of referents following a 1 > 2 > 3 hierarchy and the total number of referents

(Smeets 1989: 177–9; Salas 1992a: 99–100).

(22) in

y

ˇce amu-a-n temuko n

y

ipukarukatu

21

in

y

ˇcin

y

I go-F-1.SG.ID Temuco 1P.SG PL neighbour C.1.PL

‘I shall go to Temuco with my neighbours.’

(lit.: ‘I shall go to Temuco my neighbours all of us.’)

(Salas 1992a: 99)

Characteristic of this construction is that there are always at least two referents in-

volved, but that only one of them needs to be overtly expressed. In that case the addressee

has to derive person and number of the referent not mentioned by subtracting the per-

son and number features of the overt participant from the person and number features

conveyed by the comitative marker (Augusta 1990: 125–7). For instance, in (23) the

unexpressed referent is the child’s mother.

(23) ta-mi pn

y

en

y

emu

DC-2P.SG child (of woman) C.2.D

‘you and your child (addressing a woman)’

(lit.: ‘your child, the two of you’)

(Augusta 1990: 126)

When a verb is part of the construction, it may follow the comitative marker and agree

with it in person and in number (24).

(24) eymnin

y

ˇcin

y

amu-a-yin

y

you.PL C.1.PL go-F-1.PL

‘You people will go with me.’

(lit.: ‘You (plural), we (plural), all of us will go.’)

(Augusta 1990: 125)

20

Salas (1992a: 99) calls these markers grupalizadores ‘group makers’.

21

The word karukatu ‘neighbour’ has been derived from the expression ka ruka ‘the next house’

(from ka ‘other’ and ruka ‘house’).

522 5 The Araucanian Sphere

A prefix-like element that serves the purpose of indicating a location is pu.Itis

used with nouns referring to places, as in pu ruka ‘at home’, pu wariya ‘in town’.

Its homophone pu is used mainly with nouns referring to human beings to indicate

plural (25).

(25) n

y

ipuwe

ny aku-a-y

1P.SG PL friend arrive-F-3.ID

‘My friends will arrive.’

(Smeets 1989: 91)

Other nominal plural markers are -ke and -wen. The former is used with modi-

fiers, in particular, adjectives. It is a distributive suffix translatable as ‘each’ (26).

22

Valdivia (1606: 10) considers its use a characteristic of the southern Beliche Indians. The

suffix -wen indicates pairs that generically belong together; the stem refers to one of the

members of the pair (27).

(26) fˇca-ke ˇce

old-DB human

‘old people’

(27) fo

t

ˆ

m-wen

son (of man)-GP

‘father and son’

(Augusta 1966: 53)

As in Quechua and Aymara, the verb in Mapuche typically consists of a root fol-

lowed by one or more optional derivational affixes and an inflectional block. The latter

comprises negation, mood, tense, personal reference and nominalisation. The personal

reference markers in Mapuche are of considerable interest. As in the case of the pronouns

and possessive modifiers, there is a three-way distinction both in person (first, second,

third) and in number (singular, dual, plural). In the case of first and second person,

number marking is compulsory; with third person it is optional. Person and number of

subject are generally expressed in the verb; if there is an object, person and number of

the object can also be expressed in the verb. The combined codifications of subject and

object are traditionally referred to as ‘transitions’ (transiciones), a concept which goes

back to a sixteenth-century Quechua grammar (cf. section 3.2.6), and which was further

developed by Valdivia (1606).

23

22

The parallelism with the way the affix -kama is used in Quechua is remarkable.

23

The concept of ‘transition’ as used by Peter S. DuPonceau (1760–1844) and other founding

fathers of the North American descriptive tradition in linguistics may have been borrowed from

one of the Araucanian grammars (Mackert 1999).

5.1 Araucanian or Mapuche 523

Table 5.3 Mapuche subject endings

Indicative Conditional Imperative

1 pers. sing. -(

)n -l-i -ˇci

1 pers. dual -yu -l-iu -yu

1 pers. plur. -yin

y

-l-iin

y

-yin

y

2 pers. sing. -(

)y-mi -(

)l-mi -

ŋ

e

2 pers. dual -(

)y-mu -(

)l-mu -mu

2 pers. plur. -(

)y-m

n-(

)l-m

n-m

n

3 pers. -(

)y -l-e -pe

A feature of Mapuche distinct from Aymara and Quechua is that a third-person object

can also be codified within the verb form. When both the subject and the object are third

person, there are two possibilities. These are illustrated in (28) and (29).

(28)

l

ˆ

aŋŋm-fi-y

24

kill-3O-3.ID

‘He killed him.’

(We are talking about X; X killed Y.)

(29)

l

ˆ

aŋŋm-e-y-ew

kill-I-3.ID-3.OV

‘He killed him.’

(We are talking about X; Y killed X.)

The third-person object indicated by -fi-in(28) refers to an entity or person which plays

a less dominant role in the discourse than the referent of the subject. The latter is in focus

at the moment of speaking. In (29) it is the other way round: the referent of a third person

which is in focus is the patient of an action effectuated by a third-person actor who is not

yetinfocus at the moment of speaking.

25

The two third-person categories emerging from

this opposition have been interpreted in terms of a proximate–obviative distinction as

known from the grammatical tradition of the Algonquian languages (Arnold 1996). The

third person in focus is the proximate, whereas the one not in focus is termed obviative.

The endings which indicate grammatical person and number of a subject exhibit many

formal similarities with the personal pronouns and possessive modifiers. They vary

according to moods, three in number, with which they can be combined: the indicative

mood (marker -y-or-∅-), the conditional mood (‘if’; marker -l-), and the imperative–

hortative mood (no specific marker). Table 5.3 shows the subject endings that correspond

to each mood.

As can be seen from table 5.3, the indicative marker -y-isonly clearly present in the

second-person endings; in the first person non-singular and in the third person a fusion

24

After -fi- the pronunciation of the suffix -y is optional (cf. Smeets 1989: 65).

25

One may be tempted to interpret these forms as passives. However, Mapuche also has a true

passive (suffix -

ŋ

e-), which can only be used when the actor is unexpressed.