Yamaguchi H. Engineering Fluid Mechanics (Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6 Newtonian Flow

0

T

uu

r

for

R

d

r

2

(6.3.68)

which implies

0

w

w

r

\

and 0

w

w

T

\

(6.3.69)

At infinity,

fo

r

TTT

T

T

eeee

ˆˆˆˆ

sincos

rrr

UUUu

(6.3.70)

which implies that

T

\

2

sinUr

r

w

w

and

TT

T

\

cossin

2

Ur

w

w

(6.3.71)

Equation (6.3.71) gives

\

at

for

by the integration of

TT

T

\\

\\

22

sin

2

1

Urddr

r

d

w

w

w

w

³³³

(6.3.72)

Equation (6.3.72) might assume the form of the solution in Eq. (6.3.67) as

T

\

grf

(6.3.73)

In order to seek a solution in Eq. (6.3.67), it may be appropriate to set

TT

2

sin g and substitute Eq. (6.3.73) for Eq. (6.3.64), where

0sin

2

2

2

22

2

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

T

rf

rdr

d

(6.3.74)

In order to satisfy Eq. (6.3.74) for

r

and

T

simultaneously, we must sat-

isfy

0

2

2

22

2

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

rf

rdr

d

(6.3.75)

The solutions of f in Eq. (6.3.75) must satisfy the following differential

equation (equidimentional equation)

0884

24

c

cc

cccc

ffrfrfr

(6.3.76)

Equation (6.3.76) is the so-called Euler’s differential equation, to which the

general solution to this equation is given as

314

6.3 Basic Flows Derived from Navier-Stokes Equation

4

4

2

32

1

rcrcrc

r

c

rf

(6.3.77)

where constants

1

c ,

2

c ,

3

c and

4

c are determined from the boundary con-

ditions in Eqs. (6.3.68) and (6.3.69). The final solution in Eq. (6.3.73) is

given with the aid of the functional form of Eq. (6.3.73) where

T\

2

3

3

2

sin

2

1

2

3

1

2

1

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

r

R

r

R

rU

(6.3.78)

Equation (6.3.78) also gives the velocity components as

T

cos

2

1

2

3

1

3

3

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

r

R

r

R

Uu

r

(6.3.79)

T

T

sin

4

1

4

3

1

3

3

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

r

R

r

R

Uu

(6.3.80)

Knowing the velocity field given in Eqs. (6.3.79) and (6.3.80), we can

obtain the pressure field by substituting Eqs. (6.3.79) and (6.3.80) into Eqs.

(6.3.63) and (6.3.64), and carrying out the integration to yield

T

,rp as

³³³

w

w

w

w

f

2

0

cos

2

3

r

RUpd

p

dr

r

p

dprp

T

KT

T

T

,

(6.3.81)

where

f

p is the pressure at infinity, i.e. fo

r

.

As another point of correspondence, it will now be shown that the drag

force

D

F , which is the net force acting on the sphere in the flow direction

i in Fig. 6.7, may be calculated by obtaining the stress component

x

t

on

the sphere in direction

i . This will be done by knowing the stress vector t

on the sphere as follows

jiji

eeIJeet

TTWTTW

WW

T

TT

cossinsincos

rrr

rrrrrr

p

pp

ˆˆ

I

ˆ

T

ˆ

(6.3.82)

The stress component

x

t is thus

T

W

T

W

T

sincos

rrrx

pt ti

(6.3.83)

where

rr

W

and

T

W

r

are components of the viscous stress tensor of a New-

tonian fluid, and which are given by the following constitutive equations

315

6 Newtonian Flow

r

u

r

rr

w

w

0

2

KW

,

»

¼

º

«

¬

ª

w

w

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

w

w

T

KW

T

T

r

r

u

rr

u

r

r

1

0

(6.3.84)

The velocity components

r

u and

T

u of Eqs. (6.3.79) and (6.3.80) are then

substituted into the relationship in Eq. (6.3.84), and consequently

x

t will

be obtained as

U

R

pt

x

0

2

3

cos

K

T

f

(6.3.85)

Thus, as a result, the drag force

D

F is calculated to integrate

x

t over the

spherical surface

S

dU

RU

ddRtdStF

x

S

xD

0

0

2

00

2

3

6

sin

SK

SK

ITT

SS

³³³

(6.3.86)

It is noted that

T

cos

f

p does not contribute the drag

D

F due to its

symmetry, as previously described, indicating that the potential flow,

which has only a contribution of

T

cos

f

p , does not influence the drag,

but only that the viscous contribution found in Eq. (6.3.85) does in the case

of viscous flow. If the drag coefficient

D

c is defined such that

s

D

D

AU

F

c

2

21

U

(6.3.87)

where

s

A is the frontal area of the sphere. Then we can reduce Eq. (6.3.86)

to give the drag coefficient in terms of the Reynolds number

RedU

F

c

D

D

24

421

22

SU

(6.3.88)

If 10

.Re , which implies a small sphere in a high viscous fluid, the

Stokes’ law is valid and for a sphere at the terminal velocity

U

, the buoy-

ant force

b

F plus the drag force

D

F become equal to the gravity force

g

F ,

that is

Equation (6.3.86) states that at the creep flow limit the drag force is line-

arly proportional to the speed of flow passing a small sphere (or a descend-

ing sphere with a constant speed). This is called Stokes’ law.

316

6.3 Basic Flows Derived from Navier-Stokes Equation

gg

s

dUdd

U

S

SKU

S

3

0

3

6

3

6

(6.3.89)

An important application of Eq. (6.3.89) is to measure the viscosity

0

K

by

measuring the terminal velocity

U for a falling sphere in a transparent cyl-

inder, containing the viscous fluid to be tested. According to Eq. (6.3.89)

0

K

can be obtained where

U

d

s

18

2

0

g

UU

K

(6.3.90)

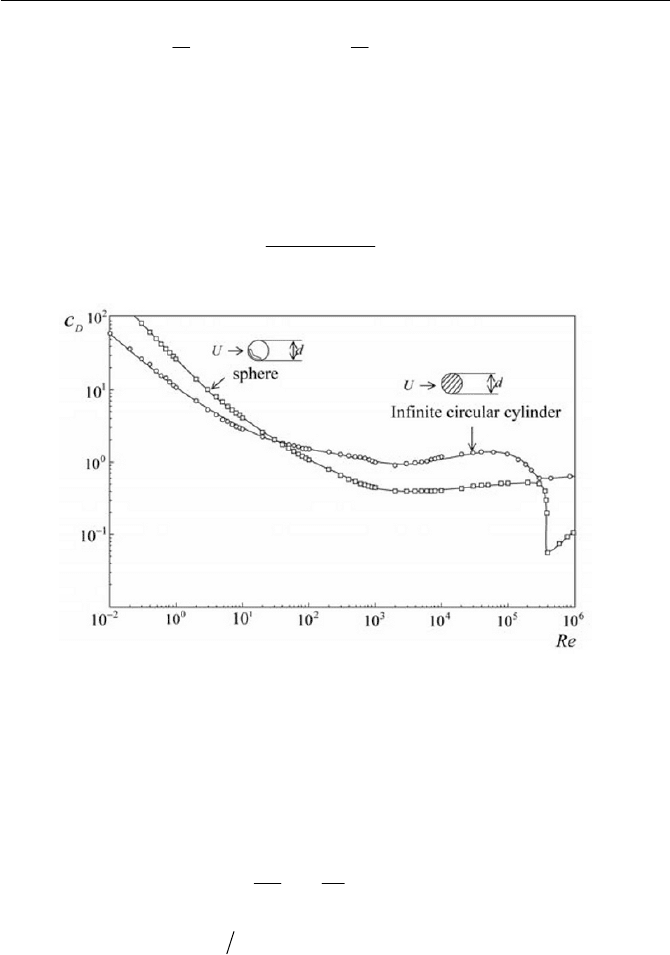

Fig. 6.8

D

Drag coefficient of a sphere and an infinite cylinder

sources, and data for

4

10tRe

is

replotted after Achenback, 1971

and 1972)

The drag coefficient

D

c

given by Stoke’s law, i.e. Eq. (6.3.88), is fur-

ther extended to validate in higher Reynolds numbers by Oseen (1910)

n

D

Re

Re

c

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

16

3

1

24

(6.3.91)

where 1

Re for sm1 u . If n is chosen at 0.5, Eq. (6.3.91) is extended

to

100|Re . Typical changes of

D

c versus Re are displayed in Fig. 6.8 for

a sphere and an infinite cylinder for the sake of comparison. It is seen in

both cases at approximately

55

105103 uu| ~Re , there is a sudden drop

(From various

317

6 Newtonian Flow

in the value of

D

c . This is due to phenomena caused by a transition of

laminar flow to turbulence. The boundary layer, which is described in

more detail in later sections, is the cause of this phenomenon.

Problems

6.3-1 Describe how the resultant flow between the concentric rotating cyl-

inders can be used as a means of measuring the viscosities of fluids.

Give comments on the feasibility of the method of measuring vis-

cosity.

6.3-2 A slipper-pad bearing is running with a speed of

sm2

1

U

. The rep-

resentative dimensions are such that,

m1080

4

0

u .h

,

m1040

4

u .

l

h

and m30. l . The viscosity of the lubricant oil is

sPa102

5

0

u

K

at a constant operating temperature. Find the total

load-bearing capacity to maintain the gap. Also calculate the drag-

lift ratio.

Ans.

»

»

¼

º

«

«

¬

ª

u

5

max

106550

N354

.

.

FF

F

D

6.3-3 Design an appropriate experimental apparatus for examining a poten-

tial flow around an infinite cylinder.

6.3-4 A small sphere of diameter

d and density

s

U

is dropped from a rest

position in a viscous fluid with density

U

. Write the equation of mo-

tion of this sphere and find the terminal velocity. The viscosity of the

fluid is

0

K

. Assume that the Stokes’ law is in effect to the motion of

the sphere.

Ans.

»

»

»

»

¼

º

«

«

«

«

¬

ª

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

0for

18

6

3

66

0

3

0

33

dt

dU

U

dUdd

dt

dU

d

s

ss

K

UU

U

S

SKU

S

U

S

2

gd

g-g

6.3-5 Find the time elapsed to the fall distance m010

. l for a sphere of

m101

5

u d and

33

mkg105u

s

U

released from a position of

rest in a viscous fluid of viscosity

sPa101

1

0

u

K

and the density

33

mkg102u

U

.

Ans.

>@

s. 9001 Appox.

318

6.4 Flow Through Pipe

6.4 Flow Through Pipe

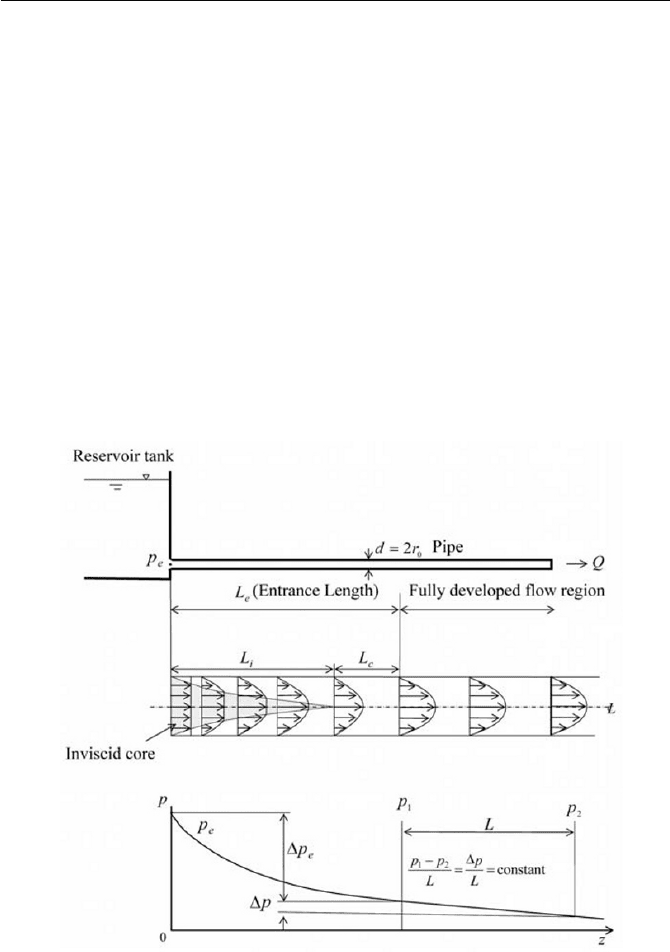

The circular pipe flow is probably the most celebrated viscous flow in the

development of fluid dynamics, in view of the fundamental importance of,

as well as, basic fluid engineering applications. We shall start to consider a

straight circulation pipe connected to a reservoir tank, as illustrated in Fig.

6.9. In many practical engineering applications, a pipe is usually connected

to a reservoir tank or a source, and the flow in the pipe starts to move for-

ward, downstream. Note that the entrance is supposed to be a bell mouth

shape to avoid boundary layer separation. There will be an “entrance ef-

fect”, where a shear layer (boundary layer; details of which will be studied

in later section) on the pipe wall and an inviscid core (uniform constant ve-

locity region along axis of the pipe) that develops toward the downstream

of flow near the entering region of the pipe.

Fig. 6.9 Circular pipe flow though entrance

319

6 Newtonian Flow

As indicated in Fig. 6.9, the shear layer grows and meets at the axis as the

inviscid core disappears within the length

i

L

termed as the inviscid core

length, at which the viscous stress dominates the entire cross section. The

profile then continues to change due to the viscous effect until a developed

flow is achieved, where the length is often termed as the profile develop-

ment region

c

L . The total length

ci

LL is called the entrance length

e

L ,

and after which the flow is fully developed, where the velocity profile

across the cross section does not change toward the downstream.

6.4.1 Entrance Flow

The entrance length for a laminar flow can be correlated in the forms

Re

d

L

e

0650. (Boussinesq, 1891 and Nikuradse, 1933)

(6.4.1)

h

h

e

Re

d

L

05050 .. (Shah and London, 1978)

(6.4.2)

where Reynolds number

Re is based on the average velocity U through a

cross section area and the diameter

d , i.e.

X

dURe . Note that the

Shah-London correlation is valid for an arbitrary pipe shape in a cross sec-

tion, where

h

d is the hydraulic diameter (four times hydraulic radius

h

r ),

which is defined by

h

p

h

r

l

A

d 44

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

(6.4.3)

where

A is the cross-section area and

p

l is the wetted perimeter, that pe-

rimeter where the fluid is in contact with the solid boundary. The limit of

the Reynolds number is approximately 2300 for engineering applications,

whereas with carefully controlled conditions the Reynolds number may go

up to higher values in excess of 40,000.

For a turbulent flow, the situation is somewhat different from the lami-

nar case. In order to observe the entrance length

e

L

of the fully developed

turbulent flow, an extra length may be needed for the detailed structure of

the turbulent flow to develop in addition to the profile development region.

For the high turbulent strength flow at the inlet of the pipe, the entrance

length

e

L is given by the following correlation at the Reynolds numbers

normally encountered

320

6

1

44 Re

d

L

e

.

4025 ~ (Nikuradse, 1933)

(6.4.4)

The pressure variation along the pipe length from the inlet is sketched

in Fig. 6.9, where the inlet pressure is

e

p . The pressure loss at the entrance

length occurs due to an acceleration of flow, i.e. the kinetic energy loss,

and the viscous friction loss. The pressure loss

e

p solely due to the ki-

netic energy loss can be estimated in consideration of the energy flux at a

representative cross sectional area as follows

Ur

EE

p

ef

e

2

0

S

(6.4.5)

where

f

E

and

e

E are the kinetic energy through a cross section of pipe at

the entrance length

e

L and the inlet respectively. They are, therefore,

given by the following formula

³

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

0

0

2

2

2

1

r

eandf

rdruuE

SU

(6.4.6)

For the laminar flow, the velocity profile in the fully developed flow is

given by well known Hagen-Poiseuille flow, which will be explained in

the subsequent section (with reference to Eq. (6.4.33)), as follows

2

0

12

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

r

r

Uru

(6.4.7)

where, at the inlet of the pipe, the velocity profile can be assumed to be

constant where

Uru

(6.4.8)

Substituting Eqs. (6.4.7) and (6.4.8) into Eq. (6.4.6) and calculating

e

p

from Eq. (6.4.5), we can obtain

2

2

Up

e

U

(6.4.9)

If the pressure loss coefficient

]

based on a loss of head is defined by

'

'

'

'

6.4 Flow Through Pipe 321

6 Newtonian Flow

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

gg 2

2

Up

e

]

U

(6.4.10)

]

is obtained for the laminar flow as

1

]

(6.4.11)

In the case of the turbulent flow,

]

is given by 71 power law (Eq.

6.4.53)

090

.

]

(6.4.12)

The actual pressure loss (defining

0

]

]

as the total pressure loss co-

efficient) at the entrance length is usually higher than that of the kinetic

energy loss due to the viscous friction loss, and they are found by using the

Hagen’s experiments

71

0

.

]

for laminar flow

(6.4.13)

40

0

.

]

without bell mouth entrance for turbulent flow

(6.4.14)

In the flow beyond the entrance length the pressure variation tends to

decrease linearly along the axial distance

z and the pressure gradient

L

p

L

pp

z

p

w

w

21

(6.4.15)

is kept constant for both the laminar and turbulent flows.

For

e

Lz ! , the velocity becomes a solely axial and only with the lateral

coordinates in the fully developed flow in a circular pipe, as sketched in

Fig. 6.9, where the flow is non-accelerating and is driven by the pressure

gradient (when the gravitational body force is ignored for a horizontal

straight pipe or, if at all, it can be incorporated in the pressure term as the

potential energy function). In general terms, such a (nearly) non-

accelerating flow of an incompressible Newtonian fluid in a steady state of

motion is treated as the so-called Stokes’ equation, which is written with

the continuity equation as follows

0 u

(6.4.16)

'

'

6.4.2 Fully Developed Flow in Pipe

322

and

0

2

0

u

K

p

(6.4.17)

It should be noted that the Stokes’ equation (6.4.17) is reduced from the

Navier-Stokes equation Eq. (6.1.7), by setting the inertia term zero, and is

valid for not so large Reynolds number where the flow tends to become

turbulent. The flow field derived from Eq. (6.4.17) is independent of the

density, and the flows followed in Eq. (6.4.17) are so-called creeping flows,

even though the Reynolds number need not be small (and in fact the Rey-

nolds number is not even a required parameter).

It is now desired to consider the fully developed, pressure-driven lami-

nar flow in a circular pipe where the flow is assumed to be steady, axi-

symmetric and rectilinear. This flow is termed as the Hagen-Poiseuille

flow, which implies that in the flow field there is only an axial velocity

component

z

u , while the radial

r

u and circumferential

T

u velocity com-

ponents are, respectively, 0

r

u and 0

T

u . In the cylindrical coordi-

nates system

z

u may be the function of

zr ,,

T

, i.e.

zruu

zz

,,

T

. How-

ever with the condition of axisymmetry, i.e.

0

w

w

T

z

u

(6.4.18)

and from the mass continuity

0

w

w

z

u

z

(6.4.19)

z

u is only the function of

r

, i.e.

ruu

zz

. In the fully developed recti-

linear flows, the pressure gradient in the axial direction is kept constant as

is referred to in Eq. (6.4.15), i.e.

c

z

p

w

w

const.

(6.4.20)

It will prove useful to consider the nondimensionalization of the

Stokes’ equation in Eq. (6.4.17), which can be carried out by taking the

pipe radius

0

r

as follows

0

r

r

r

*

,

zpr

u

u

z

ww

2

0

0

K

*

(6.4.21)

Resultantly we have

6.4 Flow Through Pipe 323