Xin Q. Diesel Engine System Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

700 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

compression stroke increases as EGR rate, or essentially the soot amount in

the EGR gas, increases, while the piston friction in the mid of each stroke

reduces at high EGR rate (Urabe et al., 1998). The reason was believed that

the soot deposited in the top ring groove made the piston rings slide on the

soot particles attached to the cylinder bore surface and caused an increase

in the boundary friction coefcient and wear on the components.

Piston ring axial dynamic motions (ring lifting, twisting, and uttering) and

groove design signicantly affect blow-by and oil consumption. They may

also impact ring friction and wear via the changes in inter-ring pressure and

ring tilting. The ring motion is affected by the ring gap. Too large a ring gap

results in excessively large blow-by, power loss, and emissions. Too small a

ring gap leads to ring butting problems at high operating temperatures. The

gap in the second ring can be properly designed to increase the top ring’s

sealing ability by preventing the inter-ring pressure from building up and

lifting the top ring off the bottom of the groove.

Ring thickness signicantly affects oil lm thickness and ring friction.

Furuhama et al. (1981) conducted experiments and theoretical calculations

to nd that the decrease of the ring thickness may not necessarily reduce

friction because it decreases the oil lm thickness at the same time. The

reduced lm thickness can increase the friction force and wear around the

TDC and the BDC. Off-centered barrel shape prole has been found as the

optimum for the top compression ring. The optimum choice of the degree of

curvature of the barrel prole is a trade-off between the mid-stroke and end-

stroke performance. A highly curved prole gives a large oil lm thickness

in mid-stroke due to the strong ‘wedge effect’, resulting in low friction.

However, the oil lm thickness falls rapidly around the TDC and the BDC,

and the ‘squeeze lm effect’ is weak there, resulting in high wear. A atter

ring face prole behaves oppositely.

Piston ring tension is another important parameter for friction. A piston

ring design procedure to dene a free shape producing circumferentially

uniform contact force distribution was provided by Ma et al. (1996). Oil

ring tension is an important design parameter since it determines whether

the oil ring operates in the hydrodynamic or boundary lubrication regime.

It also controls the amount of oil that is available for other rings. Uras and

Patterson (1985) used the instantaneous IMEP experimental method to nd

that the friction of a 70 N high-tension oil ring decreased signicantly after

break-in, but still higher than the friction of a 17.8 N low-tension oil ring.

When the surface roughness increases, the ratio of the piston ring oil lm

thickness to roughness decreases. When the ratio is less than a threshold value,

mixed lubrication occurs. A higher roughness results in a larger proportion

of mixed lubrication and a higher friction power loss.

Oil viscosity is also important for ring friction. Friction modiers in the

oil may reduce boundary lubrication friction, with the degree of friction

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 700 5/5/11 12:00:33 PM

701Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

reduction varying based on the oil formulation. Oil starvation usually

occurs more severely at full load ring than motoring. This contributes to

thinner oil lm thickness and higher friction at full load (Sanda et al., 1997).

Uras and Patterson (1984, 1985) found that the piston assembly friction

force increased when the oil viscosity became either too high or too low.

As viscosity increases, the hydrodynamic lubrication regime is promoted

and the boundary lubrication is depressed. Glidewell and Korcek (1998)

conducted experimental work to nd that oil starvation increased the friction

coefcient, most noticeably in the mid-stroke region. They also found that

the effectiveness of the friction modier signicantly degraded with aged

engine oil. Richardson and Borman (1992) found that the temperature rise

in the oil lm due to viscous heating was negligibly small. They indicated

that the cylinder inner wall temperature should be used to determine the oil

viscosity for modeling.

10.5.2 Piston ring lubrication dynamics

Piston ring pack lubrication modeling was overviewed by Dowson (1993).

The calculations of inter-ring gas pressure and blow-by (Kuo et al., 1989)

provide key input data of gas pressure for ring dynamics and friction

calculations. The gas mass ow rate between the adjacent volumes (at the

ring gap, circumferential gap, and the ring side clearance) is calculated

by using the orice ow equations. Ring motion (e.g., ring radial collapse

and axial uttering) is very sensitive to the inter-ring pressures. There is a

strong coupling between the inter-ring pressure and the ring motion. The

characteristics of inter-ring gas pressures and ring lift motion were researched

by Furuhama et al. (1979), Curtis (1981), Dursunkaya et al. (1993), Chen

and Richardson (2000), and Herbst and Priebsch (2000) using experimental

and numerical investigations.

The piston ring lubrication dynamics has several levels of complexity,

from low to high as follows:

∑ one-dimensional Reynolds equation for a ring pack with the closed-form

analytical solution with various lubrication cavitation boundary conditions

(e.g., half-Sommerfeld, the mass-conservation Reynolds or JFO condition)

and under fully or partially ooded boundary condition

∑ one-dimensional Reynolds equation with the closed-form analytical

solution including surface asperity and mixed lubrication models

∑ one-dimensional Reynolds equation with numerical solutions

∑ one-dimensional Reynolds equation coupled with ring axial and twist

dynamics

∑ two-dimensional Reynolds equation with numerical solutions

∑ two-dimensional Reynolds equation including surface asperity and

complex mixed lubrication models

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 701 5/5/11 12:00:33 PM

702 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

∑ two-dimensional mixed lubrication coupled with ring axial and twist

dynamics

∑ including the features of elastohydrodynamic lubrication

∑ including some of the models of bore distortion, ring conformability,

ring groove deformation, ring–groove contact pressure distribution, and

lubricant rheological properties

∑ including some of the models of blow-by, oil consumption, ring face–liner

wear, and ring groove wear.

For engine system design to estimate piston ring friction, usually the rst

and second levels of model mentioned above are suf cient. They also offer

a real-time fast computation for an instantaneous crank-angle-resolution

solution. Other higher level models are suitable for component designs.

A simple one-dimensional Reynolds equation for a piston ring can be

written as

d

d

d

d

= –

d

d

+ 12

d

d

y

dyd

h

p

dpd

y

dyd

h

y

dyd

h

t

o

lu

b

o

v

o

3

6

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

mm

mm

d

mm

d

+ 12

mm

+ 12

v

mm

v

y

mm

y

dyd

mm

dyd

vP

mm

vP

v

vP

v

mm

v

vP

v

o

mm

o

10.27

where the instantaneous oil lm thickness h

o

= h

o,min

+ h

profi le

(y), h

o,min

is

the minimum oil lm thickness, y refers to the axial direction of the ring,

h

profi le

(y) is the ring face pro le as a function of the axial distance of the

ring, and p

lub

is the lubricating oil lm pressure. The detailed derivation of

the Reynolds equation was provided by Richardson and Borman (1992).

The lubricating oil lm force per unit length of the ring is given as:

Fp

A

Fp

lu

Fp

Fp

br

Fp

Fp

in

Fp

gl

Fp

gl

Fp

ub

c

inle

t

outle

t

,

Fp

,

Fp

Fp

br

Fp

,

Fp

br

Fp

Fp =Fp

Fp

gl

Fp =Fp

gl

Fp

d

Fp dFp

gl

d

gl

Fp

gl

Fp dFp

gl

Fp

ub

d

ub

Ú

gl

Ú

gl

Fp

gl

Fp

Ú

Fp

gl

Fp

inle

Ú

inle

d

Ú

d

Fp dFp

Ú

Fp dFp

Fp

gl

Fp dFp

gl

Fp

Ú

Fp

gl

Fp dFp

gl

Fp

Ú

gl

Ú

gl

Fp

gl

Fp

Ú

Fp

gl

Fp

d

Ú

d

Fp dFp

Ú

Fp dFp

Fp

gl

Fp dFp

gl

Fp

Ú

Fp

gl

Fp dFp

gl

Fp

10.28

The ring diametrical dynamics is given by a force balance as:

mx

FF

F

ri

mx

ri

mx

ng

mx

ng

mx

ri

ng

gas

FF

gas

FF

tensio

FF

tensio

FF

nl

F

nl

F

ub

ri

ng

=

FF FF

FF

gas

FF FF

gas

FF

FF+ FF

nl

–

nl

,

–

–– –

F

gr

F

gr

F

oov

e

10.29

where x

ring

is the diametrical displacement of the ring at each moment of

time, and F

groove

is the lateral friction force between the ring and the ring

groove per unit length of the ring. With the mass inertia term

mx

ri

mx

ri

mx

ng

mx

ng

mx

ri

ng

included in the dynamic formulation, equations 10.27 and 10.29 generate

a stiff ODE system which requires a higher stiff-order implicit numerical

integration scheme with strong B-stability (for B-stability, see Hairer and

Warner (1996)).

Usually, the inertia term and the ring groove force are small and can be

neglected for simplicity. Then, with the load balanced by the lubricant force

in the normal (diametrical) direction, equation 10.29 becomes

F

~

gas

+ F

~

tension

= F

~

lub,ring

10.30

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 702 5/5/11 12:00:34 PM

703Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

which determines the required oil lm thickness and the ‘squeeze lm’

term to satisfy this force balance. The friction force of the piston ring can

be calculated as

FF

F

fr

FF

fr

FF

in

FF

in

FF

gf

FF

gf

FF

ri

ng

hf

F

hf

F

ri

ng

b

,,

fr,,fr

in,,in

gf,,gf

,,

ng,,ng

hf,,hf

,

ng,ng

FF =FF

FF

gf

FF =FF

gf

FF

gf

gf

FF

gf

FF FF

gf

FF

ri

ri

ng

ng

hf

hf

+

hf

+

hf

=

∂

pA

cf

Af

cf

Af

ri

cfricf

ba

pA

ba

pA

sp

pA

sp

pA

erity

pA

erity

pA

A

c

c

Ê

Ë

ˆ

¯

ÚÚ

ÚÚ

v

ÚÚ

v

h

ÚÚ

h

h

ÚÚ

h

v

ÚÚ

v

P

ÚÚ

P

o

ÚÚ

o

o

ÚÚ

o

+

ÚÚ

+

m

ÚÚ

m

2

ÚÚ

2

∂

ÚÚ

∂

ÚÚ

ppp

ÚÚ

ppp

∂p∂p∂p∂

ÚÚ

∂p∂p∂p∂

y

ÚÚ

y

Af

ÚÚ

Af

lu

ÚÚ

lu

b

ÚÚ

b

cf

ÚÚ

cf

Af

cf

Af

ÚÚ

Af

cf

Af

A

ÚÚ

A

∂

ÚÚ

∂

y∂y

ÚÚ

y∂y

Ê

ÚÚ

Ê

Ë

ÚÚ

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

ÚÚ

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

ÚÚ

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

ÚÚ

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ÚÚ

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

ÚÚ

ˆ

¯

ÚÚ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ÚÚ

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

ÚÚ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ÚÚ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ÚÚ

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ÚÚÚÚ

dd

AfddAf

pAddpA

cf

dd

cf

Af

cf

AfddAf

cf

Af

ri

dd

ri

cfricf

dd

cfricf

ba

dd

ba

pA

ba

pAddpA

ba

pA

pA

sp

pAddpA

sp

pA

pA

erity

pAddpA

erity

pA

ÚÚ

dd

ÚÚ

Af

ÚÚ

AfddAf

ÚÚ

Af

Af

cf

Af

ÚÚ

Af

cf

AfddAf

cf

Af

ÚÚ

Af

cf

Af

Af+Af

ÚÚ

Af+AfddAf+Af

ÚÚ

Af+Af

Af

cf

Af+Af

cf

Af

ÚÚ

Af

cf

Af+Af

cf

AfddAf

cf

Af+Af

cf

Af

ÚÚ

Af

cf

Af+Af

cf

Af

,

10.31

where p

asperity

is the asperity contact pressure of the ring. The rst term in

the hydrodynamic friction force is the viscous shear term due to the Couette

ow, and the second term is the hydrodynamic pressure term due to the

Poisseuille ow. The friction power loss due to the translation or squeeze

term in the lubrication is neglected here.

The closed-form analytical solution for the one-dimensional Reynolds

equation 10.27 was provided by Ting and Mayer (1974a, 1974b), Dowson

et al. (1979), Wakuri et al. (1981), Furuhama et al. (1981), Jeng (1992a,

1992b, 1992c), and Sawicki and Yu (2000).

Oil starvation of the piston ring means the oil does not cover the entire

ring face. Oil starvation modeling at the leading edge (i.e., inlet) of the

ring can be as simple as assuming an effective ring thickness as input (e.g.,

assuming 50% of the ring face covered by oil), or can be as complex as

predicting the oil starvation boundary with oil transport and ow continuity

models. Oil starvation happens often on piston rings. Modeling the

starvation is important for the prediction of oil lm thickness and friction

loss. The oil supplied to each ring is dependent upon the amount of the

oil left on the cylinder wall by the preceding ring. In the downstroke the

leading ring can be assumed fully ooded. Usually, fully ooded inlet

condition can be assumed for the second rail of the oil control ring during

the downstroke. Starved lubrication should be assumed for all other rings

during the downstroke. Partially ooded lubrication should be assumed for

all the rings during the upstroke. The compression rings have more severe

oil starvation conditions during ring than motoring. During ring in the

upward strokes, the inlet of the two compression rings and the upper rail

of the oil control ring have oil starvation. In the downward strokes, the

inlet of the two compression rings has oil starvation. Ma and Smith (1996)

suggested that the bottom ring in a ring pack can be treated as fully ooded

on the downstroke in the model. Oil starvation with the one-dimensional

Reynolds equation in mixed lubrication was modeled by Sanda et al. (1997).

They found the predicted oil lm regions with starvation were as small as

half of the total thickness of the compression rings, and the predicted oil

lm thickness with starvation was less than half of the oil lm thickness

predicted by the fully ooded condition for the compression rings, resulting

in much greater friction force. They also found that the starved lubrication

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 703 5/5/11 12:00:35 PM

704 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

simulation for the oil control ring matched the measured data much better

than the fully ooded simulation, and the starved simulation gave about

35% higher friction force than the fully ooded simulation data.

Cavitation and separation modeling at the trailing edge of the piston ring

is important for the oil pressure distribution. The assumption of the cavitation

boundary condition at the trailing edge of the ring in the modeling signicantly

affects the calculated hydrodynamic lubrication pressure distribution prole,

load capacity, oil lm thickness, and friction force of the ring. When negative

pressures in the lubricating oil lm occur, gas bubbles are formed as cavities

from the dissolved gases or ventilation to the surroundings. The oil lm ruptures

to lose any hydrodynamic lubrication pressure. The cavitated oil lm has the

atmospheric pressure. The viscous shear force in a cavitated/ruptured oil lm,

although not as high as in a non-cavitated oil lm, cannot be neglected. The

full-Sommerfeld boundary condition unrealistically requires the lubricating oil

lm to continuously sustain large negative pressures. The half-Sommerfeld

condition simply discards the negative pressures hence violates ow continuity

and mass conservation. The Reynolds (Swift–Stieber) cavitation condition

obeys mass conservation by requiring the pressure gradient equal to zero

at the cavitation boundary. The Reynolds condition is the most commonly

used condition for piston rings although other cavitation assumptions have

been proposed in tribology (e.g., the ow separation boundary condition,

the Floberg condition, the Coyne and Elrod separation condition, and the

JFO boundary condition).

Unlike the piston skirt, a large gas pressure may exist at the outlet of the

lubricated region for piston rings. This results in the oil lm reforming after

the cavitation by generating a hydrodynamic pressure gradually rising to the

outlet gas pressure at the trailing edge of the ring. This cavitation–reformation

sequence forms a cavitated ‘pocket’ within the oil lm near the outlet.

Pressure reformation may have strong effects on the peak oil lm pressure

in the full-lm region and on the cavitation location (Yang and Keith, 1995).

Some authors believe that when a negative pressure happens the oil lm

completely separates from the ring face and does not reform at the outlet.

As a result, the outlet gas pressure is applied in the entire original negative

pressure region all the way back to the separation boundary. Richardson and

Borman (1992) reported that there was no indication of oil lm reforming

at the rear of the ring in their measurement. This indicated that separation

occurred rather than ventilation cavitation. It seems that the JFO or Elrod

cavitation model used in the journal bearings cannot be used in the piston

ring and skirt. Ma and Smith (1996) proposed that it is more reasonable to

assume an ‘open cavitation’ without oil lm reformation. Piston ring lubrication

cavitation modeling with different boundary conditions was reviewed by

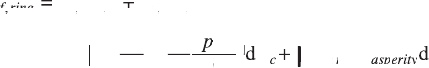

Priest et al. (1996, Fig. 10.18). They showed that the most commonly used

Reynolds cavitation and reformation boundary condition produced thinner

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 704 5/5/11 12:00:35 PM

705Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

oil lm thickness and higher shear friction force than the modied Reynolds

reformation condition of separation without reformation. They showed that

the Reynolds condition gave 34% higher FMEP than the modied one.

Arcoumanis et al. (1995) and Sawicki and Yu (2000) compared different

cavitation conditions for piston ring lubrication. Although the calculation

results from these authors are very sensitive to the choice of cavitation

boundary condition, there is neither consensus nor solid experimental evidence

on which condition is more appropriate. The half-Sommerfeld condition

predicts thinner oil lm thickness than the Reynolds condition does. It seems

the Reynolds cavitation and reformation boundary condition is still the most

effective to date for piston ring lubrication. Moreover, it should be noted

that the difference in the friction force caused by the different cavitation

boundary conditions is usually much smaller for the piston skirt than the

piston rings. This is partly because the two sides (thrust and anti-thrust) of

the skirt tend to offset or balance each other on the overall oil lm thickness

and shear friction around the piston when one side produces thinner lm

thickness than the other side.

U

p

p

x

x

U

p

1

p

1

p

2

p

2

x

1

x

1

x

2

x

2

x

3

x

4

Cavitated region

Crank angle (degree)

(a) Hydrodynamic pressure profile and

film shape with Reynolds cavitation and

reformation boundary conditions

(b) Hydrodynamic pressure profile and

film shape with modified Reynolds

separation boundary conditions

F (N)

100

50

0

–50

–100

0 180 360 540 720

Reynolds cavitation and reformation

Modified Reynolds separation

(c) Predicted cyclic variation of friction force

10.18 Piston ring lubrication dynamics, cavitation, and friction

modeling (from Priest et al., 1996).

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 705 5/5/11 12:00:35 PM

706 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

Surface topography plays a dominant role in mixed lubrication. Both

surface roughness pattern (oriented in the transverse, isotropic, or longitudinal

direction) and roughness magnitude have signicant inuence on piston

ring oil lm thickness, friction and wear. A rougher surface increases the

proportion of boundary friction, in the mixed lubrication. The piston ring

surface topography effect in the mixed lubrication was modeled by Sui and

Ariga (1993) and Michail and Barber (1995). Sui and Ariga (1993) concluded

that the friction of the oil ring and the second compression ring is the most

sensitive to surface roughness variations, while the top compression ring is

less affected by surface roughness. Tian et al. (1996b) studied the effect of

surface roughness on oil transport in the top liner region. Arcoumanis et al.

(1997) developed mixed lubrication models for Newtonian and non-Newtonian

shear thinning uids on rough surfaces. Gulwadi (2000) introduced a model

to calculate the ring–liner wear.

The forces and moments due to gas pressures, axial inertia, hydrodynamic

normal and shear forces and the reaction and friction forces at the ring–groove

pivot positions cause the ring to move axially and twist in the groove. Ruddy

et al. (1979), Keribar et al. (1991), Tian et al. (1996a, 1997, 1998), and

Gulwadi (2000) extended the axisymmetrical one-dimensional Reynolds

equation lubrication analysis by including the ring dynamics of the radial,

axial, and twist motions within the groove so that blow-by, oil consumption

and ring–groove wear can be analyzed in addition to a more accurate prediction

of ring friction. Tian et al. (1996a) also introduced a lubrication and asperity

contact model for the oil lm pressure between the ring and its groove.

Piston ring hydrodynamic lubrication and friction are signicantly affected

by the dynamic twist of the ring and the inter-ring gas pressure loading that

is inuenced by the ring axial motion. The inuences of particles on the

tribological performance of piston ring packs were numerically studied by

Meng et al. (2007b, 2010). Piston ring dynamics modeling can be conducted

with commercial software packages such as Ricardo’s RINGPAK (Keribar

et al., 1991; Gulwadi, 2000) and AVL’s EXCITE Piston&Rings and GLIDE

(Herbst and Priebsch, 2000).

The lateral dynamic friction force between the piston ring and the ring groove

is believed to be signicant, and this partly contributes to a circumferential

variation of the oil lm thickness of the ring. Non-axisymmetrical oil lm

distribution is also caused by other factors such as circumferentially non-

uniform ring elastic pressure (e.g., caused by improper design of the ring

free shape), bore distortion, the circumferential variation of the ring face

prole, dynamic ring twist, the non-uniform static twist caused by ring

groove deformation, circumferential ring gap position, and the different/

asymmetrical inter-ring gas pressures at the thrust and anti-thrust sides due

to the piston secondary motions. The modeling work by Das (1976) was

one of the earliest efforts to solve the two-dimensional Reynolds equation

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 706 5/5/11 12:00:35 PM

707Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

for piston rings. Two-dimensional piston ring lubrication was modeled in

detail by Hu et al. (1994), Yang and Keith (1996a, 1996b), and in a series

of research conducted by Ma and Smith (1996) and Ma et al. (1995a, 1995b,

1997), particularly modeling the effects of bore out-of-roundness and ring

eccentricity on ring friction and oil transport. The non-axisymmetrical

modeling gives circumferentially non-uniform hydrodynamic lubricating

oil lm pressure distribution and uneven oil lm thickness. Yang and Keith

(1996b) found that the circumferential ow lowers the load-carrying capacity

of the ring, hence the minimum oil lm thickness in the non-axisymmetrical

modeling is smaller than that in the axisymmetrical modeling. Ma et al.

(1995b) found that better overall ring performance can be achieved when

the ring face barrel prole has a small offset (i.e., asymmetric barrel).

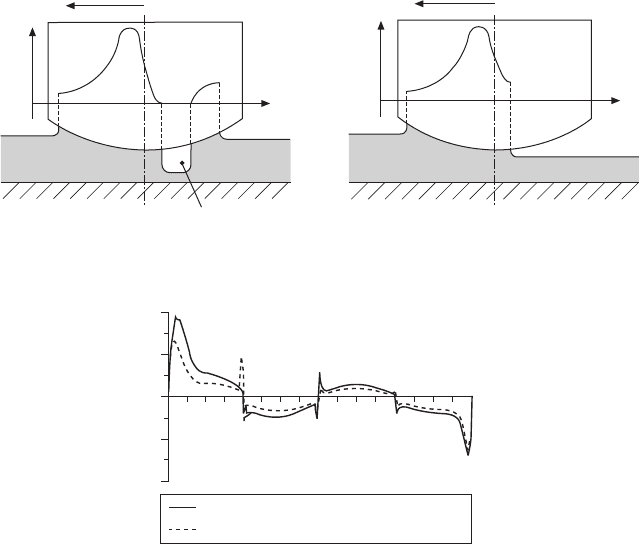

Piston ring elastohydrodynamic lubrication was modeled by Yang and

Keith (1995, 1996b) with one- and two-dimensional Reynolds equations,

respectively, by considering the pressure–viscosity relation and ring elastic

deection and deformation. They found that the elastohydrodynamic effect

is a strong factor in piston ring lubrication because their calculated minimum

oil lm thickness around the TDC is thicker than that in the rigid ring

case (Fig. 10.19). They also found that under high cylinder pressures the

elastohydrodynamic oil lm thickness tends to be uniform circumferentially

because the elastic deformation of the ring tends to reduce the gap caused

by the noncircular bore.

Two-dimensional elastic ring

Two-dimensional rigid ring

One-dimensional EHL

–360 –180 0 180 360

Crank angle (degree)

Minimum film thickness (mm)

3.5 ¥ 10

–3

3 ¥ 10

–3

2.5 ¥ 10

–3

2 ¥ 10

–3

1.5 ¥ 10

–3

1 ¥ 10

–3

5 ¥ 10

–4

0

10.19 Comparisons of predicted oil film thickness of a piston ring

(from Yang and Keith, 1996b).

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 707 5/5/11 12:00:35 PM

708 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

10.6 Engine bearing lubrication dynamics

Engine bearing tribology has been extensively researched and there is a large

body of literature available. A broad discussion in this highly specialized eld

is outside the scope of this book. Excellent reviews have been provided by

Campbell et al. (1967), Martin (1983, 1985), Goenka and Paranjpe (1992),

Taylor (1993a), and Tanaka (1999). The following discussion focuses on the

key characteristics of engine bearing lubrication dynamics, general analysis

methods, and bearing friction calculation.

10.6.1 Characteristics of engine bearing lubrication

dynamics

The engine bearings are dynamically loaded bearings, including the crankshaft

main bearings, the connecting rod bearings, the piston pin bearings, the

camshaft bearings, and the balancer shaft bearings. The analytical solutions

of the Reynolds equation for bearing lubrication were usually based on the

‘short bearing’ approximation. Booker’s mobility method (Booker, 1965)

to calculate the journal trajectory and the oil lm thickness of dynamically

loaded bearings was very popular and is still being used in many commercial

software packages for the calculations of oil lm thickness and friction. The

mobility method determines the journal eccentricity and the attitude angle

for a given dynamic force.

A more accurate solution of the journal trajectory and friction loss requires

a numerical algorithm such as nite difference or nite element to solve the

two-dimensional Reynolds equation. The mass inertia effect of the journal

within the bearing clearance may become important for some bearings. It may

impact the journal trajectory, for example in the crankshaft main bearings

near the ywheel. The journal bearing dynamics including the mass inertia

or the moment of inertia term (or the acceleration term) coupled with the

Reynolds equation possesses a fundamental characteristic of stiff ODE. Stiff

ODE requires a time-marching implicit numerical integration algorithm with

superior numerical stability in order to avoid (1) the round-off error going out

of control in any explicit integration algorithm, or (2) an arti cial oscillation

of the lubricant force with respect to time caused by a less stable implicit

integration algorithm. The stiffer the ODE system, the more dif cult the

numerical integration. A more detailed discussion of the stiff ODE feature

is summarized in Section 10.4.4. One important indicator of the stiffness

of the ODE system is the largest eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix of the

ODE, which is related to the lubrication and dynamic parameters of journal

bearings as follows (Xin, 1999):

l

m

ODE

l

ODE

l

,m

ODE,mODE

ax

vB

m

vB

m

B

JB

rL

vB

rL

vB

mc

JB

mc

JB

µ

3

rL

3

rL

3

10.32

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 708 5/5/11 12:00:36 PM

709Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

where m

v

is the lubricant dynamic viscosity, r

B

is the bearing radius, L

B

is

the bearing length, m

J

is the journal mass, c

B

is the bearing radial clearance.

Equation 10.32 is derived using the short-bearing assumption. A larger

l

ODE,max

means higher stiffness of the ODE. Equation 10.32 shows the major

parameters affecting the stiffness. For example, a large value of oil viscosity,

a very light journal mass or a very small bearing clearance can all increase

the severity of the numerical instability in the time-marching integration,

especially when an explicit integrator is used.

Stiff ODE is one of the most important fundamental characteristics of any

lubrication dynamics problem when the mass inertia or moment of inertia

term is included in the dynamics equation of the motion coupled with the

Reynolds equation. Correctly handling stiff ODE is critical for the robustness

and the computational efciency of the model. Fortunately, in many practical

applications of lubrication dynamics, the mass inertia effect is small hence

the inertia term may be neglected for simplicity. However, the inertia term

should be included if a rigorous dynamic formulation is adopted. In this case

the stiff ODE feature is inevitable.

The complexity of the bearing models can vary from a simple level of

the rigid isothermal two-dimensional hydrodynamic lubrication with the

half-Sommerfeld (non-mass-conserving) cavitation boundary condition

to a sophisticated level of thermo-elastohydrodynamic three-dimensional

lubrication including the effects of journal tilting, surface topography, and

non-Newtonian uid with the JFO mass-conserving cavitation boundary

condition, and the Elrod algorithm to solve the boundary condition. Although

a true mass-conserving cavitation boundary condition has a secondary effect

on the calculations of oil lm thickness, oil lm pressure, and friction loss,

it is important for the oil ow and temperature predictions (Goenka and

Paranjpe, 1992). The half-Sommerfeld and Reynolds cavitation conditions

do not satisfy the condition that the oil inow should equal the outow,

whereas the JFO condition does. For engine system design calculations,

usually a simplied short-bearing approximation is sufcient to estimate

the bearing friction. Paranjpe et al. (2000) provided a comparison between

the theoretical calculations and the oil lm thickness measurements for the

engine crankshaft main bearings and the connecting rod big-end bearings.

The relationship between the typical instantaneous bearing load and the oil

lm thickness behavior of those bearings was illustrated. An example of the

instantaneous bearing friction torque simulation with a mixed lubrication model

for dynamically loaded journal bearings was provided by Ai et al. (1998).

Bearing oil operating temperature and operating viscosity have a large

impact on the accuracy of friction calculations. The friction generated inside

the bearing in turn heats the oil as it ows through the bearing. Therefore,

the estimation of the bearing oil temperature and viscosity needs to account

for the viscous heating due to the uid shear friction. The rate of the viscous

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 709 5/5/11 12:00:36 PM