Xin Q. Diesel Engine System Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

680 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

10.4 Piston-assembly lubrication dynamics

10.4.1 Friction characteristics and piston assembly design

From the perspective of multi-body dynamics modeling, the piston assembly

includes the piston skirt, the rings, the piston pin (SAE J2612, 2002), and

the connecting rod. The discussion in this section focuses on the lubrication

dynamics of the piston body and the skirt. The piston rings will be discussed

in Section 10.5. The piston pin bearing, the connecting rod big-end bearing,

and the crankshaft main bearing are discussed in Section 10.6.

The piston in modern diesel engines needs to have strong thermo-mechanical

strength to withstand the peak cylinder pressure and the temperature. It also

needs to have low friction and wear, low piston slap noise, good control on

skirt distortion, proper cooling and lubrication, and light weight (for high-

speed operation), and match with the combustion chamber shape. Piston rings

seal the in-cylinder gas with little blow-by, transfer heat from the piston to

the cylinder liner, and control the lube oil consumption. Low-friction piston

assembly design is very important for fuel consumption. Both analytical and

experimental methods play critical roles in piston tribological design.

Piston slap has been identied as the main cause of the cylinder liner

cavitation in heavy-duty diesel engines due to the high impact energy of the

slap. Piston slap noise can also be the most prominent mechanical noise during

warm-up. Mechanical noises emitted from the engine surface are caused by

the impact between the components and the resulting vibration. They become

louder as the engine speed increases. In piston tribological design, the piston

skirt friction power, the dynamic minimum lubricating oil lm thickness, and

the cold piston slap kinetic energy (or noise) are the three most important

performance parameters that should be optimized simultaneously.

While undergoing a primary reciprocating motion inside the cylinder, the

piston is pushed laterally by the alternating side thrust force from the thrust

side to the anti-thrust side, and vice versa, several times within the skirt-

to-bore clearance during an engine cycle. The side thrust force is generated

by the reaction force from the connecting rod small end, which is a force

generally not in the piston’s sliding direction, to resist the combined gas and

inertia forces. The lateral (transverse) motion is accompanied by a small

tilting motion around the piston pin due to the moments acting on the piston

from various forces. These secondary motions cause the piston to slap on

the cylinder bore at skirt top and bottom, accompanied by a sliding motion

changing from mixed lubrication at the TDC or the BDC to hydrodynamic

lubrication at the mid-stroke. Piston-assembly dynamics is an area related to

piston skirt secondary motions (lateral and tilting) and their associated piston

slap, friction, and wear. Its research started in the 1960s, evolving from the

single-body dynamics without lubrication to the more complex multi-body

dynamics coupled with elastohydrodynamic lubrication models.

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 680 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

681Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

The piston secondary motions not only affect the piston slap noise (to be

detailed in Chapter 11), but also affect the piston ring operation and wear.

In order to achieve low blow-by and oil consumption, the piston lateral

movement and titling need to be minimized to provide a good platform for

the piston rings to operate (Wacker et al., 1978). Large piston tilting may

cause the rails of the oil control ring to move away from the cylinder wall

so that the ring loses its oil control ability. The piston secondary motions

also affect the diesel cylinder bore polishing which is caused by the top land

carbon deposit (Guertler, 1986). Moreover, the piston secondary motions

affect piston skirt friction, and this topic is detailed below.

Piston skirt lubrication and friction are affected by the skirt-to-bore clearance

and the oil lm thickness distribution on the skirt which is related directly to

the side thrust and the piston secondary motions. The piston-assembly friction

of diesel engines can account for 40–55% of the total engine mechanical

friction (Richardson, 2000), with the piston skirt contributing about 15–20%,

the piston rings 15–20%, and the connecting rod 10–14%.

Piston skirt friction characteristics have been researched extensively. Feuga

and Bury (1984) measured the friction force and power loss of a gasoline

piston–ring–liner assembly at various engine speeds and loads, and with

different lubricant oil grades. They found that the piston-assembly FMEP

(including the rings) increased with engine speed and load. At higher loads the

frictional loss in the expansion stroke was higher than that in other strokes,

and this characteristic was especially prominent at low speeds. Wakabayashi

et al. (2003) found from measurement that the effect of gasoline engine load

on the piston skirt friction during the expansion stroke was small. Nakayama

et al. (1997) measured the piston skirt friction force of a gasoline engine and

found that the piston skirt could operate in the mixed lubrication regime in

the expansion stroke, and the friction force in the rst half of the expansion

stroke could be reduced by changing the piston pin offset from the thrust

side to the anti-thrust side.

Many design parameters affect piston-assembly dynamics. For example, the

secondary movement can be reduced or diminished by using smaller clearance,

piston pin offset or optimized skirt prole. An early comprehensive summary of

the design guidelines was given by Winship (1967). He pointed out that a thin

thickness of the major thrust side of the upper skirt was especially important

for noise control, and a shorter skirt length (measured from the piston pin

centerline) affected piston tilting, blow-by, and oil consumption. Oetting et al.

(1984) illustrated that a reduced reciprocating mass and a long connecting rod

(i.e., reduced crank–conrod ratio) reduced the piston side thrust and achieved

low piston slap noise. Uras and Patterson (1987) measured piston friction and

found that friction did not increase with increased piston weight.

Mansouri and Wong (2004) used numerical simulation for a natural gas

engine to nd that the piston skirt friction power was inversely proportional

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 681 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

682 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

to the oil lm thickness and approximately directly proportional to the surface

waviness. The ‘waviness’ refers to the circumferential machining tracks of

saw-tooth shape for oil retention on the surface to prevent scufng. It is two

orders of magnitude higher than the surface ‘roughness’. They also found

that a atter skirt prole and a less rigid skirt could reduce the proportion of

the boundary lubrication relative to the hydrodynamic lubrication friction. It

should be noted that signicant boundary lubrication scraping may occur during

the expansion stroke, especially for the skirts having large waviness.

Crankshaft offset is another important parameter extensively investigated by

many researchers (Haddad and Tjan, 1995; Nakayama et al., 2000; Wakabayashi

et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2004). Crankshaft offset may reduce the piston side

thrust and skirt tilting; and it may reduce piston friction during the expansion

stroke if the friction occurs in the boundary or mixed lubrication regime. In

fact, as long as the piston skirt is designed to stay within the hydrodynamic

lubrication regime, any side thrust change basically would not affect the skirt

friction appreciably. Crankshaft offset has a strong interaction with piston pin

offset and piston pin vertical position. Crankshaft offset may either promote

or destroy the hydrodynamic lubrication on the skirt, resulting in different

conclusions on piston skirt friction accordingly.

Piston skirt prole design was addressed using an experimental method

by Yagi and Yamagata (1982). They used a composite material (epoxy resin)

to cover the piston skirt surface and run the engine to naturally wear off the

material at highly stressed areas. Finally the smoothly curved, barrel-shape

piston skirt prole dened by the composite material remaining after the

marking test was adopted as the nal optimized cold prole. With this method,

different proles to minimize wear and scufng at the thrust and anti-thrust

sides can come out of a real engine test. It should be noted that the prole

produced by such a marking method minimizes the wear and scufng only for

a given piston design (e.g., with a given pin offset). Different piston designs

may produce different resulting proles. This method cannot identify which

design gives the desirable minimum piston tilting. Piston dynamics simulation

is able to complement that aspect and is an important tool in piston design.

Teraguchi et al. (2001) conducted experimental work on a small diesel

engine and found that a forced oil supply remarkably reduced the skirt friction

force by 20% in the expansion stroke on the thrust side and the latter half of

the exhaust stroke, without a signicant penalty on oil consumption. They

found that the effectiveness was equivalent to the friction reduction achieved

by using a MoS

2

coated skirt.

10.4.2 History of piston-assembly lubrication dynamics

Although piston slap can be modeled effectively with multi-body dynamics

to calculate the side thrust and the titling moment without using a skirt

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 682 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

683Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

lubrication model, such a model cannot be used to predict skirt friction

accurately because in reality the skirt operates mainly in the hydrodynamic

lubrication regime and hence the oil lm thickness simulation becomes critical.

Dry contact modeling with Coulomb friction yields unrealistically high skirt

friction force compared to the normal engine operation with lubrication.

Piston-assembly dynamics modeling without lubrication will be discussed

in more detail in Chapter 11 for the topic of piston slap noise.

Unlike the piston ring lubrication which can be reasonably simplied as

a one-dimensional problem of lubricating oil lm pressure distribution only

along the axial direction because the ring can be regarded circumferentially

uniform, the piston skirt lubrication must be modeled as a two-dimensional

problem for oil lm pressure distribution. The lubrication modeling for

the piston skirt with the rigid-body assumption and the numerical solution

of the two-dimensional Reynolds equation was conducted by Knoll and

Peeken (1982), Li and Ezzat (1983), Zhu et al. (1992), Chittenden and

Priest (1993), Nakada et al. (1997), and Livanos and Kyrtatos (2006). Oil

starvation and cavitation modeling is important for predicting the piston

secondary motions. Keribar and Dursunkaya (1992a) showed in simulation

that the piston secondary motions under fully ooded and partially ooded

skirt lubrication were signicantly different.

Piston thermal deformation was simulated with a nite element model by

Li (1982). Piston skirt elastic deformation was simulated by Kimura et al.

(1999). The piston skirt experiences signicant deformations caused by thermal

expansion, mechanical loading, and lubricating oil lm pressure, especially

for the thinner, more exible light-duty or articulated piston skirts. Typical

skirt deformations are of the same order of magnitude as, or larger than,

the skirt-to-bore clearances. Elastohydrodynamic lubrication for the piston

skirt has been modeled by Oh et al. (1987), Blair et al. (1990), Goenka and

Meernik (1992), Keribar and Dursunkaya (1992a, 1992b), Dursunkaya and

Keribar (1992), Keribar et al. (1993), Zhu et al. (1993), Dursunkaya et al.

(1993, 1994), Wong et al. (1994), Knoll et al. (1996), Scholz and Bargende

(2000), Offner et al. (2001), and Shah et al. (2007).

Goenka and Meernik (1992) compared three lubrication models with

experimental data. The three models are: (1) a simple model considering only

the ‘squeeze effect’ and the lateral motion by ignoring the ‘wedge effect’

and the tilting motion; (2) a rigid-body hydrodynamic lubrication model

by ignoring the thermal expansion and the compliance; and (3) a mixed-

elastohydrodynamic lubrication (DEHD) model. They concluded that both the

rigid-body and DEHD models could predict piston skirt friction reasonably

well, while the simple model was only acceptable for trend predictions.

The DEHD model was recommended for more accurate analysis used in

component design. Dursunkaya et al. (1993) pointed out that, compared to

the elastohydrodynamic lubrication simulation, the rigid skirt hydrodynamic

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 683 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

684 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

lubrication model could yield large discrepancies in the boundary friction.

Knoll et al. (1996) used a nite element method to present small differences

in piston secondary motions between the rigid and the elastic skirt simulation

results for a diesel engine. Carden et al. (2006) concluded that a relatively

simple model could be used to provide credible predictions of piston assembly

friction loss even if the model did not have the advanced features such as

elastohydrodynamic lubrication, nite element, and bore distortion.

Sophisticated piston skirt lubrication dynamics modeling can be conducted

with commercial software packages, such as Ricardo’s PISDYN (Keribar

et al., 1993; Carden et al., 2006) and AVL’s GLIDE. The simulation of

deformable-piston dynamics coupled with elastohydrodynamic lubrication

can also be conducted with commercial nite-element software packages, as

performed by several authors mentioned above (Knoll et al., 1996; Scholz

and Bargende, 2000; Offner et al., 2001).

10.4.3 Formulation of piston-assembly lubrication

dynamics

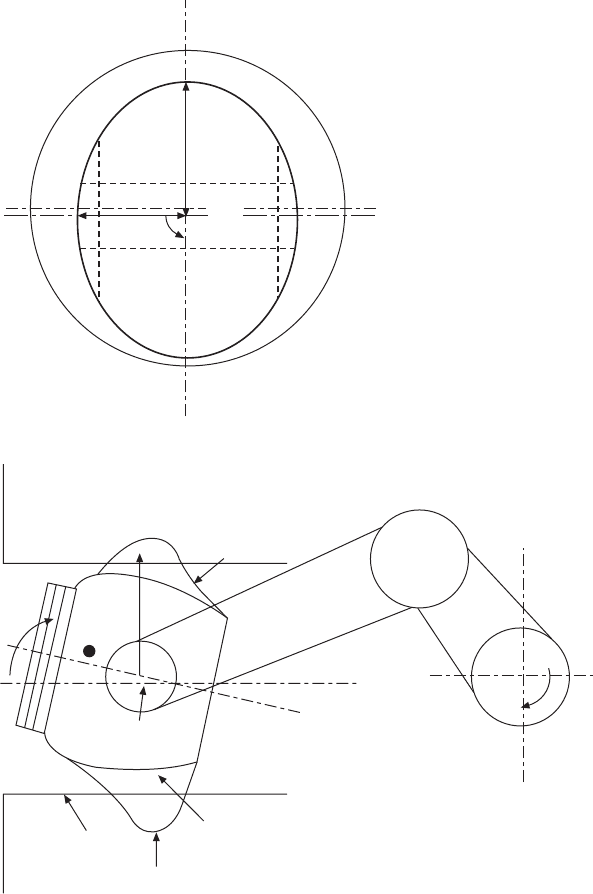

An analytical model of piston lubrication dynamics is shown in Fig. 10.6.

The following design and operating parameters affect the piston dynamics:

(1) piston mass (including the piston pin); (2) connecting rod mass; (3) piston

tilting moment of inertia; (4) connecting rod rotating moment of inertia; (5)

piston skirt-to-bore clearance; (6) piston center of gravity positions (lateral

and vertical); (7) piston pin positions (lateral and vertical); (8) piston skirt

length; (9) piston skirt lubrication wetted arc angle; (10) piston skirt axial

prole and ovality; (11) lubricant oil viscosity; and (12) engine speed and

load. The outputs of the model include the piston primary motion (i.e., the

reciprocating sliding motion) and the piston skirt secondary motions (i.e., the

lateral and tilting motions within the skirt-to-bore clearance), the lubricating

oil lm thickness and the pressure distribution on the piston skirt, the friction

forces in the hydrodynamic lubrication regime and the metal-to-metal contact

scraping regime.

The analytical model includes piston assembly multi-phase multi-body

dynamics coupled with piston skirt lubrication. The side thrust (the lateral

force acting on the piston pin) results from the cylinder gas pressure and the

inertia forces, and induces the piston lateral motion. Piston tilting is caused

by the moments acting on the piston skirt from various forces (i.e., the side

thrust, the vertical force acting on the piston pin, the cylinder pressure,

the lubricating oil lm forces (also called lubricant forces), the friction

forces between the skirt and the rings, and the piston pin friction force).

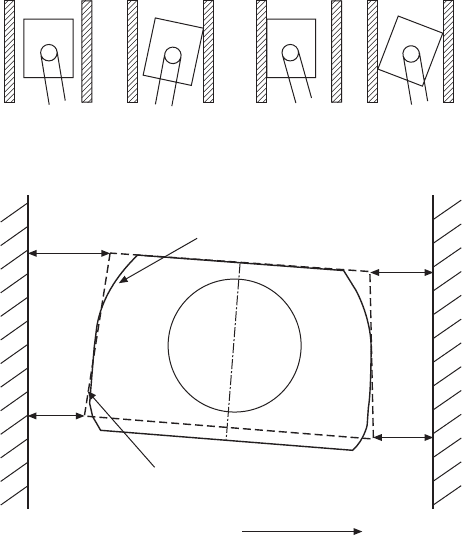

The multi-phase used in the dynamic modeling includes a normal phase

without scraping, a single-corner or single-location scraping phase, and a

two-corner or multi-location scraping phase (Fig. 10.7). The scraping refers

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 684 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

10.6 Illustration of piston-assembly lubrication dynamics model.

Thrust side

Piston

Oil film

pressure

Crank pin

Cylinder bore

Oval piston in cylindrical

bore (top view)

Crankshaft

Connecting rod

Bore centerline

Piston

centerline

C.G.

Cylinder bore

P

lub,max

oil film

pressure

Barrel skirt

profile

Piston

pin

Lateral eccentricity

from bore centerline

(positive direction)

Piston

pin

Piston

skirt

b

a

The degree of ovality = 2(a-b)

h

o

j

0

0

Anti-thrust side

Tilting angle (positive direction)

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 685 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

686 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

to the boundary lubrication. In each phase, the dynamics equations can be

formulated for each component of the piston assembly (i.e., the piston skirt

and the connecting rod) and the crankshaft based on the force balance using

Newton’s second law F = ma for the lateral and vertical motions and the

moment balance for the rotation. More details about the dynamic equations

in piston-assembly dynamics modeling are provided in Shiao and Moskwa

(1993) and Xin (1999).

The multi-body dynamics modeling approach is much more accurate than

the commonly used ‘point mass’ simplication of the connecting rod for

piston side thrust calculations. The ‘point mass’ method treats the connecting

rod as two point masses concentrated at the small end and the big end,

respectively, rather than as a rigid body. An example of the importance of

accurate formulation of the piston skirt side thrust calculation is given in Fig.

10.8. It shows that the error due to the simplied ‘point mass’ approximation

can be as great as 20%.

The transition between different phases of the motion is handled by rigid-

body impact dynamics based on the impulse and momentum balances. For

Normal phase Scraping phase 1 Scraping phase 2

Illustration of three phases of piston motion in the thrust plane

Corner 4

Corner 1

h4

h3

Real cold skirt profile

h1

h2

Piston skirt

Piston pin

Corner 3

Cylinder bore

Corner velocity positive direction

Corner 2

Simplified conic skirt shape for cold piston

slap simulation without effective lubrication

10.7 Multi-phase dynamics model of the piston and definition of

piston skirt corners.

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 686 5/5/11 12:00:28 PM

687Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

example, when the oil lm thickness becomes lower than a certain threshold

value, piston-to-liner impact is assumed to occur with a non-zero piston

lateral impact velocity. Rebound occurs after each impact, and a coef cient

of restitution is assumed for calculating the piston lateral velocity after the

rebound. When the piston impact velocity becomes suf ciently small after

a series of impact and rebound events and if there is still a non-zero normal

force pushing the piston against the bore, a scraping motion is assumed to

occur with boundary lubrication. When the normal force vanishes as the

piston side thrust changes, the piston may leave the scraping phase and

switch to a normal phase. Such a sophisticated high- delity model may not

only predict the friction during the scraping phases, but also simulate the

transient piston slap behavior before the scraping occurs.

The lubrication model is based on the viscous uid Reynolds equation.

The equation can be solved with the nite-difference numerical method for

the lubricating oil lm pressure distribution after the piston skirt secondary

motions are computed at each time step. The three-dimensional oil pressure

distribution is then integrated over the skirt surface to obtain the lubricant

force and moment, which are used in the piston dynamics model at each

time step. The Reynolds equation governing the lubricating oil lm pressure

on the piston skirt is given as (Xin, 1999):

∂

∂

∂

∂

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

∂

∂

∂

∂

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

y

∂y∂

h

p

∂p∂

y

∂y∂

r

h

p

∂p∂

o

lu

b

P

r

P

r

o

lu

b

3

2

3

1

+

∂

∂

¯

¯

¯

˜

¯

¯

˜

¯

Ë

Ë

∂

∂

Ë

Á

Ë

Ë

Á

Ë

h h

o

o

2

2

=

jj

∂

jj

∂

Ë

jj

Ë

Ë

Á

Ë

jj

Ë

Á

Ë

o

jj

o

–

61

+61 +

2

mm

61

mm

61

61

mm

61

+61 +

mm

+61 +

2

mm

2

mm

vP

mm

61

mm

61

vP

61

mm

61

o

61

o

61

61

mm

61

o

61

mm

61

v

o

61

mm

61v61

mm

61

mm

vP

mm

v

mm

vP

mm

61

mm

61

vP

61

mm

61v61

mm

61

vP

61

mm

61

h

61

h

61

y

mm

y

mm

h

t

∂

61

∂

61

∂

mm

∂

mm

61

mm

61

∂

61

mm

61

y∂y

mm

y

mm

∂

mm

y

mm

∂

∂

10.24

where y represents the axial direction of the piston skirt, j represents the

circumferential direction of the skirt, r

P

is the piston radius, h

o

is the oil

lm thickness, p

lub

is the lubricating oil lm pressure, m

v

is the dynamic

oil viscosity, v

P

is the piston sliding velocity, and t is time. Equation 10.24

shows that the oil lm pressure, the gradient of the oil lm pressure and

hence the viscous shear friction force all increase linearly with piston sliding

velocity and oil viscosity.

0 180 360 540 720

Multi-body dynamics

‘Point mass’ approximation

Crank angle (degree)

Side load on piston (N)

4000

2000

0

–2000

–4000

–6000

–8000

10.8 Piston side thrust calculated with different methods (1800 rpm,

70% load).

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 687 5/5/11 12:00:29 PM

688 Diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

The viscous shear friction force is calculated by integrating the viscous

shear stress over the lubricated area on the piston skirt. The viscous friction

force increases with the skirt length and the piston diameter, and decreases

when the skirt-to-bore clearance increases. The hydrodynamic friction

force can be calculated as the summation of the viscous shear term and the

hydrodynamic pressure term, ignoring the translation or squeeze term. The

total piston skirt friction force is equal to the sum of the hydrodynamic

friction force and the boundary lubrication friction force if any, given as:

FF

F

v

h

h

fs

FF

fs

FF

kirt

FF

kirt

FF

fs

FF

fs

FF

kirt

hf

F

hf

F

skir

tb

v

P

o

o

,,

fs,,fs

kirt,,kirt

fs,,fs

hf,,hf

FF =FF

FF FF

fs

fs

FF

fs

FF FF

fs

FF

kirt

kirt

hf

hf

+

hf

+

hf

=

+

,,,,,,

fs,,fs,,fs,,fs

kirt,,kirt,,kirt,,kirt

,

tb,tb

m

222

∂

∂

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Á

Ë

Ê

Ë

Ê

Á

Ê

Ë

Ê

ˆ

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

˜

¯

ˆ

¯

ˆ

˜

ˆ

¯

ˆ

ÚÚ

Ú

p

∂p∂

y

∂y∂

Af

Ú

Af

Ú

pA

lu

b

cf

Ú

cf

Ú

Af

cf

Af

Ú

Af

Ú

cf

Ú

Af

Ú

ri

cfricf

ba

pA

ba

pA

sp

pA

sp

pA

erity

pA

erity

pA

A

Ú

A

Ú

c

c

d+

Afd+Af

Af

cf

Afd+Af

cf

Af

d

pAdpA

,

ri,ri

10.25

where p

asperity

is the asperity contact pressure used in the load-carrying asperity

models of the mixed lubrication. For more comprehensive coverage about

the squeeze term in the friction power of bearings, the reader is referred to

Martin (1985) and Taylor (1993a). Note that on the cavitation side of the skirt,

although the friction is usually reduced by a certain extent due to the air/

vapor pockets in the ruptured lubricant lm streams, the viscous shear friction

force is still signi cant and cannot be completely neglected. The piston skirt

friction power is equal to the friction force multiplied by the piston sliding

velocity. The calculation of the friction torques at the piston pin bearing and

the conrod big-end bearing can often be simpli ed by multiplying the resultant

force with an assumed friction coef cient and the bearing radius.

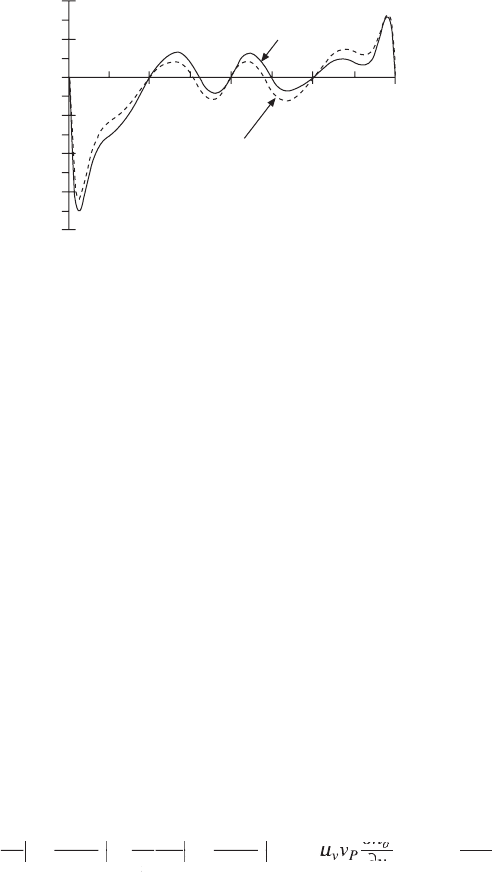

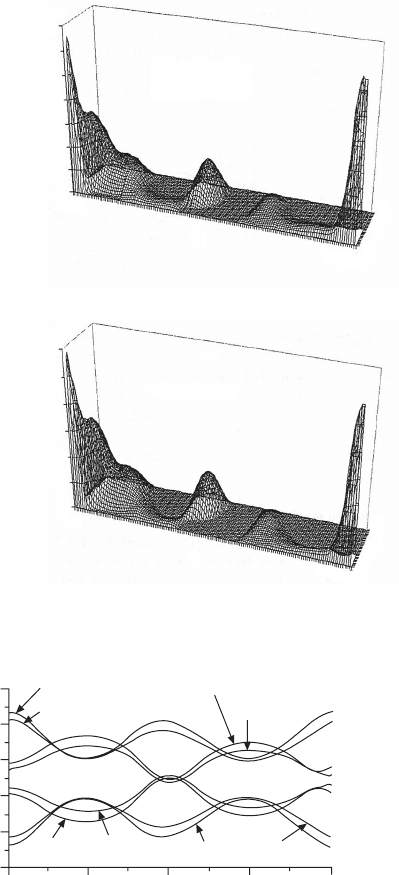

Lubrication boundary conditions are important for the prediction of the

lubricating oil lm thickness and the pressure distribution on the piston

skirt. The boundary conditions include fully ooded or partially ooded on

the skirt surface, and also include a lubricant cavitation condition once a

negative lubricating oil lm pressure is calculated. The cavitation conditions

usually include the non-mass-conserving half-Sommerfeld boundary condition

and the mass-conservation Reynolds or Jakobsson–Floberg–Olsson (JFO)

boundary condition. The comparison between different cavitation boundary

conditions for the piston skirt lubrication is provided in Fig. 10.9. It shows

that the half-Sommerfeld condition generally gives more conservative results

in the minimum oil lm thickness, i.e., smaller oil lm thickness than that

given by the Reynolds condition. However, it seems the Reynolds cavitation

boundary condition is still the most appropriate cavitation condition for

piston skirt lubrication. More sophisticated lubrication modeling such as the

elastohydrodynamic lubrication, including the effects of bore distortion and

skirt deformation as well as the more complex models of lubricant viscosity,

may be used but the computing time will increase exponentially.

The piston skirt lubrication model can simulate both a cylindrical skirt

and a non-cylindrical skirt, e.g., a barrel shape in the axial direction with

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 688 5/5/11 12:00:29 PM

689Friction and lubrication in diesel engine system design

© Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011

Lubricating oil film

pressure (Pa)

Lubricating oil film

pressure (Pa)

2,100,000

1,800,000

1,500,000

1,200,000

900,000

600,000

300,000

0

1,800,000

1,500,000

1,200,000

900,000

600,000

300,000

0

Thrust side

0°

0°

q

q

720°

720°

Pressure-time map on the thrust line (j = 90°)

with the Reynolds cavitation condition

Pressure-time map on the thrust line

(j = 90°) with the half-Sommerfeld condition

Thrust side

Skirt-to-bore clearance (mm)

0.1

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

0 180 360 540 720

Crank angle (degree)

h1 (S)

h1 (R)

h3 (S)

h3 (R)

h2 (S)

h2 (R)

h4 (S)

h4 (R)

Trajectories of piston secondary motions (the

half-Sommerfeld condition and the Reynolds

condition)

10.9 Comparison between half-Sommerfeld and Reynolds boundary

conditions of cavitation for piston skirt lubrication dynamics

(2000 rpm 70% load).

R = Reynolds condition

S = half-Sommerfield

condition

Crank angle (degree)

Crank angle (degree)

Skirt bottom

Skirt bottom

Skirt top

Skirt top

Diesel-Xin-10.indd 689 5/5/11 12:00:30 PM