Webster R., Oliver M.A., Geostatistics for Environmental Scientists

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

common logarithms to stabilize their variances, and an isotropic experimental

variogram was computed. It appears as the plotted points in Figure 5.15. Any

smooth curve through the points will have an intercept, so we include a nugget

variance in the model. By fitting single spherical and exponential functions,

with weights proportional to the numbers of pairs, we obtain the cur ves of best

fit shown in Figure 5.15(a) and (b), respectively. Clearly both fit poorly near the

ordinate. The values of the parameters, the residual sum of squares and

^

A are

listed in Table 5.2, from which it is evident that the exponential function is the

better. If we add another spherical or exponential component we obtain

the more detailed curves in Figure 5.15(c) and (d), respectively. Now the

double spherical is evidently the best, with the smallest mean squared residual.

It also has the smallest

^

A, and so in this instance we choose this more elaborate

model.

This solution is valid for weighted least-squares fitting provided the weights

remain constant, as when they are simply set in proportion to the numbers of

paired comparisons.

Webster and McBratney (1989) discuss the AIC in some detail, show its

equivalence to an F test for nes ted models, and suggest other possible criteria.

Another method for judging the goodness of a model is cross-validation. This

involves comparing kriged estimat es and their variances, and we defer it until

we have described kriging.

Table 5.2 Models fitted to the variogram of log

10

Cu in the Borders Region, estimates

of their parameters, the mean squared residual (MSR), and the variable part of the

Akaike information criterion ð

^

AÞ. The symbols are as defined in the text.

Distance

Sills parameters/km

Model c

0

c

1

c

2

a

1

a

2

r

1

r

2

MSR

^

A

Spherical 0.05027 0.01805 18.0 0.06822 128:3

Exponential 0.04549 0.02403 6.65 0.06046 134:3

Double

spherical 0.02767 0.02585 0.01505 2.7 20.5 0.02994 165:4

Double

exponential 0.00567 0.04566 0.01975 0.59 9.99 0.03616 155:7

Fitting Models 107

6

Reliability of the

Experimental Variogram

and Nested Sampling

We mentioned in Chapters 4 and 5 the importance of estimating the variogram

accurately and of modelling it correctly. This chapter deals with factors that

affect the reliability of the experimental variogram, in particular the statistical

distribution of the data, the effect of sample size on the confidence we can have

in the variogram, and the imp ortance of a suitable separating interval between

sampling points. In addition to our aim to estimate the regional variogram

reliably, we show how to use limited resources wisely to dete rmine suitable and

affordable sampling intervals.

6.1 RELIABILITY OF THE EXPERIMENTAL VARIOGRAM

Apart from the matter of anisotropy, equation (4.40) provides asymptotically

unbiased estimates of gðhÞ for Z in the region of interest, R. However, the

experimental variogram obtained will fluctuate more or less, and so will its

reliability. We now examine factors that affect these.

6.1.1 Statistical distribution

We made the point in Chapter 2 that sample variances of strongly asymmetric

or skewed (typically g

1

1org

1

1) variables are unstable. The estimates

obtained with the usual method-of-moments formula for the variogram,

equation (4.40), are variances and so are sensitive to departures from a normal

distribution. If the distribution of the variable is skewed then the confidence

limits on the variogram are wider than they would be otherwise and as a result

Geostatistics for Environmental Scientists/2nd Edition R. Webster and M.A. Oliver

# 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

the semivariances are less reliable. Skewness can result from a long upper or

lower tail in the underlying process or from the presence of a secondary process

that contaminates the primary process—values from the latter may appe ar as

outliers. Kerry and Oliver (2007a, 2007b) have studied the effects of asym-

metry in the underlying process and outliers on the variogram using simulated

fields. We summarize their results below.

Methods of estimating variograms reliably from skewed data have been

sought, and it is clear that the cause of asymmetry affects what one should

do. If the skewness coefficient exceeds the bounds given above then the

histogram or box-plot should be exam ined to reveal the deta il of the asymmetry.

In addition to these usual graphical methods, you can identify exceptional

contributions to the semivariances by drawing an h-scattergram for a given

lag, h. As described in Chapter 4, an h-scattergra m is a graph in which the zðxÞ

are plotted against the zðx þ hÞ with which they are compared in computing

^

gðhÞ. In general, the plotted points appear as more or less inflated clusters, as in

the usual kind of scatter graph.

Underlying asymmetry or skewness

Where asymmetry arises from a long tail, especially a long upper tail, in the

distribution ‘standard best practice’ has been to transform the data, as described

in Chapter 2. The variogram is then computed on the transformed data.

Transformation is not essential, however; the variogram computed from the

original data and predictions using it are unbiased, though they are not

necessarily the most precise. Perhaps more surprising is that the characteristic

form of the variogram may be changed little by transformation. So, you should

examine the experimental variograms of both raw and transformed data before

deciding which to work with.

Kerry and Oliver (2007a) explored the effects of varying skewness and sample

size, and of different transformations on random fields created by simulated

annealing (see Chapter 12 for a description of the method). They simulated

values on a square 5-m grid of 1600 points from a spherical function (equation

(5.24)), with a range, a, of 75 m, a total sill variance, c

0

þ c, of 1, and

nugget:sill ratios of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1. They simulated similar fields of

400 points and 100 points with grid intervals of 10 m and 20 m, respectively.

Values in the fields were raised to a power a to create a long upper tail in the

distribution. Five values of a were used to give skewness coefficients, g

1

, of 0.5,

1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 5.0. Here we illustrate what can happen with their results for

a ¼ 75 m, c

0

¼ 0 and c ¼ 1.

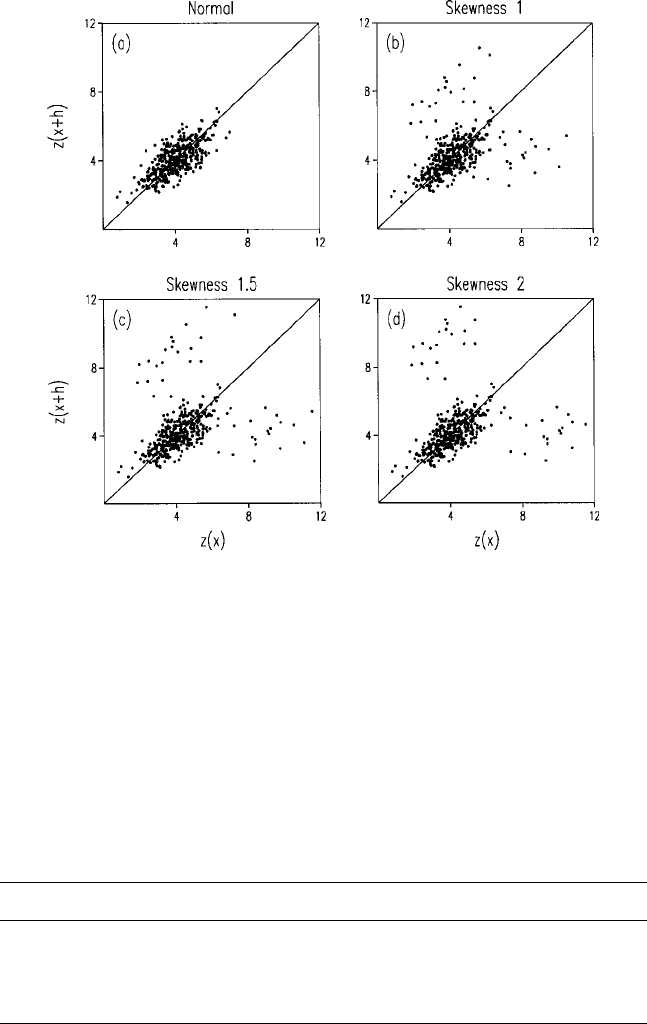

Figure 6.1 shows the h-scattergrams at lag 10 m (lag 1) from four fields

simulated on a 10 m grid. Each field has a unique coefficient of skewness,

g

1

¼ 0; 1:0; 1:5 and 2.0, caused by underlying asymmetry. The scatter of points

for the normal distribution is clustered fairly tightly along the diagonal line in

Figure 6.1(a). As the coefficient of skewness increases, the scatter becomes more

110 Reliability of the Experimental Variogram and Nested Sampling

dispersed for the larger values in the tail of the distribution reflecting the

positive skew, Figure 6.1(b)–(d). Table 6.1 lists the values of

^

rðhÞ and

^

gðhÞ for

the comparisons from these fields. The correlation coefficients decrease some-

what with inc reasing skewness, and the semivariances increase correspond-

ingly. The effects of underlying asymmetry at the first lag interval are evident,

but they are not remarkable.

Figure 6.1 The h-scattergrams for simulated fields of 400 points with underlying

asymmetry resulting in coefficients of skewness of (a) 0, (b) 1.0, (c) 1.5, (d) 2.0.

Table 6.1 Autocorrelation coefficients and semivariances for lag distance 10 m (lag 1)

computed from data simulated on a 10-m grid with four degrees of underlying skewness.

Skewness coefficient Autocorrelation coefficient Semivariance

0 0.7188 0.2700

1.0 0.6990 0.2863

1.5 0.6860 0.2984

2.0 0.6739 0.3093

Reliability of the Experimental Variogram 111

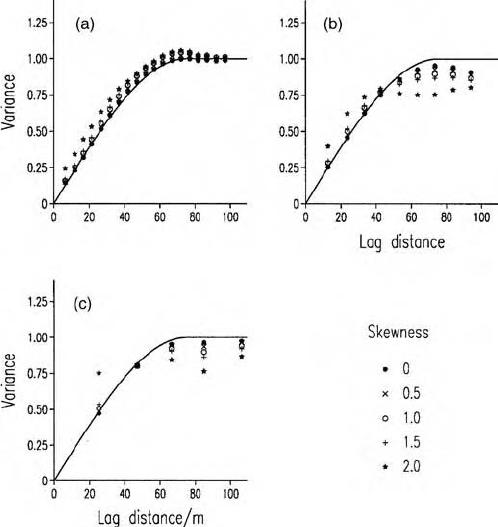

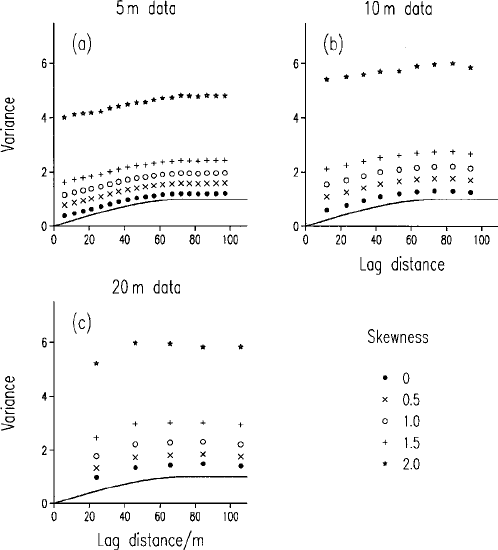

Omnidirectional variograms c omputed from the simulated fields by the

method of moments are displayed in Figure 6.2. Figure 6.2(a) shows that as

asymmetry increases the change in shape of the variogram is small for the field

on a 5 m grid. This was true even for g

1

¼ 5:0 (not shown). For the sample size

of 400 (10 m grid) the change in the shapes of the variograms is not

large, Fig ure 6. 2( b), e xc ept f or g

1

¼ 2:0. For the smaller coefficients the

semivariances are close to the generating function for the first five lags, but

beyond these they depart progessively from the sill of the generating

model. For the sample size of 100 (20-m grid), shown in Figure 6.2(c), the

semivariances at the first two lags are similar to the generating model for

g

1

¼ 0:5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0, but beyond this they depart progressively more

from t he sill varian ce of 1. T he variog ram compu te d from data with g

1

¼ 5:0

appeared as pure nugget. Evidently the effect of asymmetry decreases as the

sample size increases; it is greatest for the sample of 100 points and least for

that with 1600.

Figure 6.2 Experimental variograms (shown by point symbols) computed from

simulated fields of various sizes: (a) 1600 points (5-m grid), (b) 400 points (10-m

grid), (c) 100 points (20-m grid), with skewness caused by underlying asymmetry. The

solid lines represent the spherical generating function.

112 Reliability of the Experimental Variogram and Nested Sampling

Kerry and Oliver (2007a) found that transformation conferred little advan-

tage for large sets of data. Therefore, you should assess the desirability of any

transformation by com paring the variograms of raw and transformed data

visually before deciding whether to transform. In general, if there are no

marked differences between the shapes of the experimental variograms then

work on the raw data. This advice applies in particular if your aim is prediction,

for then the predicted values will be on the original scale of measurement,

which is what most practitioners want, and no back-transformation is needed

(see Chapter 8).

Outliers

The variogram is sensitive to outliers and to extreme values in general.

Histograms and box-plots, as described in Chapter 2, will usually reveal outliers

in the marginal distributions if they are present. All outliers must be regarded

with suspicion and investigated. Erroneous values should be corrected or

excised, and values that remain suspect are best removed, too. If by removing

one or a very few values you can reduce the skewness then it is reasonable to do

so to avoid the need for transformation or the use of robust variogram

estimators. For contaminated sites it is the exceptionally large values that are

often of interest. In this situation the variogram can be computed without the

outliers to ensure its stability, and then the values can be reinstated for

estimation and other analyses. Some practitioners remove the 98th or even

the 95th percentiles. This is too prescriptive in our view, and only values that

are obvious outliers should be removed.

It will be evident from equation (4.40) that each observed zðxÞ can contribute

to several estimates of gðhÞ. So one exceptionally large or small zðxÞ will tend to

swell

^

gðhÞ wherever it is compared with other values. The result is to inflate the

average. The effect is not uniform, how ever. If an extreme is near the edge of

the regi on it will contribute to fewer comparisons than if it is near the centre.

The end point on a regular transect, for example, contributes to the average just

once for each lag, whereas points near the mid dle contribute many times. If

data are unevenly scattered then the relative contributions of extreme values

are even less predictable. The result is that the experimental variogram is not

inflated equally over its range, and this can add to its erratic appearance.

Kerry and Oliver (2007b) examined the effect of outliers on the variogram for

skewness coefficients 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0, and for randomly located

and grouped outliers. They created normally distributed data by simulated

annealing as above for the same sizes of field. These primary fields were then

contaminated by randomly located and spatially aggregated out liers from a

secondary process.

Figure 6.3 shows four h-scattergrams at lag 10 m (lag 1), from four fields

simulated on a 10-m grid with random ly located outliers to give coefficients of

skewness g

1

¼ 0, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0. The scatter of points becomes more

Reliability of the Experimental Variogram 113

pronounced as the skewness increases from a normal distribution. For a

coefficient of skewness of 1.0, Figure 6.3(b), there is already a wide scatter of

points around a central core that represents the primary Gaussian population.

For g

1

¼ 2:0 there are now two distinct groups of points, separated from the

main group, that reflect the contaminating population. Table 6.2 supports these

Figure 6.3 The h-scattergrams for a simulated primary Gaussian field of 400 points

contaminated by outliers to give coefficients of skewness (a) 0, (b) 1.0, (c) 1.5, (d) 2.0.

Table 6.2. Autocorrelation coefficients and semivariances for lag distance 10 m (lag 1)

computed from data simulated on a 10-m grid with skewness caused by outliers.

Skewness coefficient Autocorrelation coefficient Semivariance

0 0.7188 0.270

1.0 0.3938 1.013

1.5 0.3122 1.429

2.0 0.2476 1.942

114 Reliability of the Experimental Variogram and Nested Sampling

graphical observations; the corr elation coefficients diminish markedly as skew-

ness caused by outliers increases, and also the sem ivariances increase drama-

tically.

The results in Figures 6.1 and 6.3 show how different the effects are from

different causes of asymmetry. They add strength to the statement above that

different solutions are likely to be required.

Kerry and Oliver (2007b) computed variograms as before by Matheron’s

method of momen ts and also by three robust variogram estimators proposed by

Cressie and Hawkins (1980), Dowd (1984) and Genton (1998). The estimator

of Cressie and Hawkins (1980),

^

g

CH

ðhÞ, essentially damps the effect of outliers

from the secondary process. It is based on the fourth root of the squared

differences and is given by

2

^

g

CH

ðhÞ¼

1

mðhÞ

P

mðhÞ

i¼1

jzðx

i

Þzðx

i

þ hÞj

1

2

4

0:457 þ

0:494

mðhÞ

þ

0:045

m

2

ðhÞ

: ð6:1Þ

The denominator in equation (6.1) is a correction based on the assumption that

the underlying process to be estimated has normally distributed differences over

all lags.

Dowd’s (1984) estimator,

^

g

D

ðhÞ, and Genton’s (1998 ),

^

g

G

ðhÞ, estimate the

variogram for a dominant intrins ic process in the presence of outliers. Dowd’s

estimator is given by

2

^

g

D

ðhÞ¼2:198fmedianjy

i

ðhÞjg

2

; ð6: 2Þ

where y

i

ðhÞ¼zðx

i

Þzðx

i

þ hÞ; i ¼ 1; 2; ...; mðhÞ. The term within the braces

of equation (6.2) is the median absolute pair difference (MAPD) for lag h,

which is a scale estimator only for variables where the expectation of the

differences is zero. The constant in the equation is a correction for consistency

that scales the MAPD to the standard deviation of a normally distributed

population.

Genton’s (1998) estimator is based on the scale estimator, Q

N

, of Rousseeuw

and Croux (1992, 1993), where in the general case N is the number of data.

The qua ntity Q

N

is given by

Q

N

¼ 2:219fjX

i

X

j

j; i < jg

ð

H

2

Þ

; ð6:3Þ

where the constant 2.219 is a correction for consistency with the

standard deviation of the normal distribution, and H is the integral part of

Reliability of the Experimental Variogram 115

ðN=2 Þþ1. Genton’s estimator uses equation (6.3) as an estimator of scale

applied to the differences at each lag; it is given by

2

^

g

G

ðhÞ¼ 2:219fjy

i

ðhÞy

j

ðhÞj; i < jg

ð

H

2

Þ

2

; ð6:4Þ

but now with H being the integral part of fm ðhÞ=2gþ1.

The und erlying assumption of robust variogram estimators is that the data

have a con taminated normal distribution. Lark (2000) showed that these

estimators should be used for such dist ributions and not for those where the

primary process has a simple underlying asymmetry.

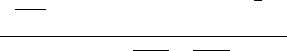

Figure 6.4 shows the experimental variograms for the three sizes of field with

randomly located outliers and for several coefficients of skewness. As the

Figure 6.4 Experimental variograms (shown by point symbols) computed from

simulated fields of various sizes: (a) 1600 points (5-m grid); (b) 400 points (10-m

grid); (c) 100 points (20-m grid), with skewness caused by randomly located outliers. The

solid lines represent the spherical generating function.

116 Reliability of the Experimental Variogram and Nested Sampling