Urry D.W. (Ed.) What Sustains Life? : Consilient Mechanisms for Protein-Based Machines and Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

3.2 Determination of Biological Structures and Their Syntheses

85

-150-

-100-

-50-

0-

50-

100-

150-

200-3

250

300-

I. Il-_ll- ill

^TT

Porcine Proinsulin

L..I..I..I.I

|1 TTl

T-l-

Tinrf

l-TIIl

Ult

•••"I

I i I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80

Residue

Residue number

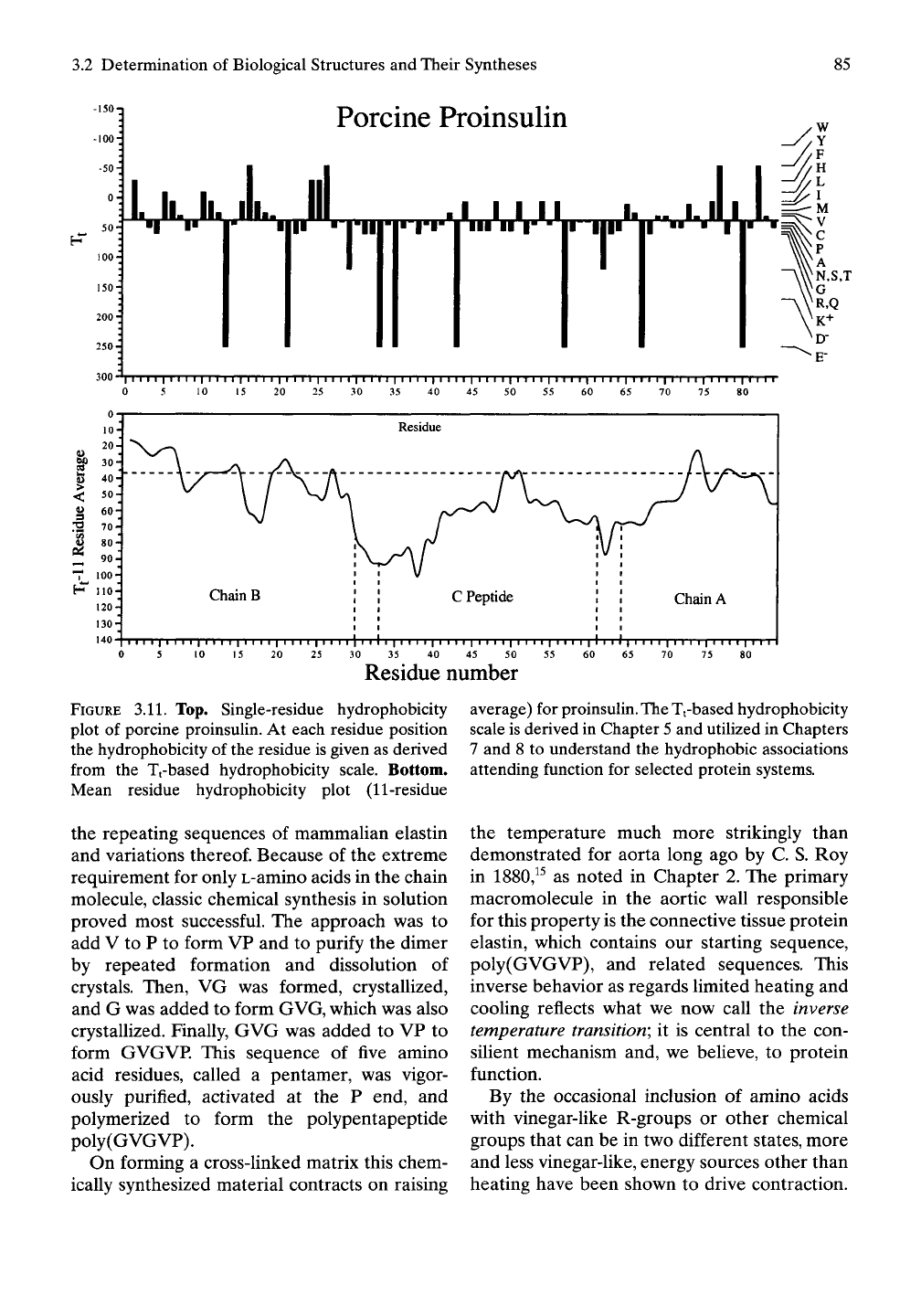

FIGURE 3.11. Top. Single-residue hydrophobicity average) for proinsulin.

The

Tfbased hydrophobicity

plot of porcine proinsuUn. At each residue position scale is derived in Chapter

5

and utilized in Chapters

the hydrophobicity of the residue is given as derived 7 and 8 to understand the hydrophobic associations

from the Tt-based hydrophobicity scale. Bottom, attending function for selected protein systems.

Mean residue hydrophobicity plot (11-residue

the repeating sequences of mammalian elastin

and variations

thereof.

Because of the extreme

requirement for only L-amino acids in the chain

molecule, classic chemical synthesis in solution

proved most successful. The approach was to

add V to P to form VP and to purify the dimer

by repeated formation and dissolution of

crystals. Then, VG was formed, crystallized,

and G was added to form GVG, which was also

crystallized. Finally, GVG was added to VP to

form GVGVP. This sequence of five amino

acid residues, called a pentamer, was vigor-

ously purified, activated at the P end, and

polymerized to form the polypentapeptide

poly(GVGVP).

On forming a cross-linked matrix this chem-

ically synthesized material contracts on raising

the temperature much more strikingly than

demonstrated for aorta long ago by C. S. Roy

in 1880,^^ as noted in Chapter 2. The primary

macromolecule in the aortic wall responsible

for this property is the connective tissue protein

elastin, which contains our starting sequence,

poly (GVGVP), and related sequences. This

inverse behavior as regards limited heating and

cooling reflects what we now call the inverse

temperature transition', it is central to the con-

silient mechanism and, we believe, to protein

function.

By the occasional inclusion of amino acids

with vinegar-like R-groups or other chemical

groups that can be in two different states, more

and less vinegar-like, energy sources other than

heating have been shown to drive contraction.

86

3.

The Pilgrimage

These are detailed in Chapter 5. When these

model proteins were subsequently made by

living organisms, using recombinant DNA

technology as described in the Chapter 2

overview, the biosynthesized model proteins

converted energies just as had the chemically

synthesized model proteins. Again, here dis-

appears the delineation of things biological in

origin from those of nonbiological origin so

prevalent when this pilgrimage began with

the accidental synthesis of urea in 1828 by

Wohler.

3.2.9.2 Structure of Elastic-contractile

Model Proteins

The family of dynamic elastic-contractile model

proteins that form the basis for the assertions

of the central message of this volume do not

lend themselves to the precise spatial descrip-

tions of proteins that form crystals. Nonethe-

less,

important structural description is possible

for the poly(GVGVP) family. Indeed, the

experimental and computational elucidation of

structure will be noted in Chapter 5. Here we

briefly provide the information in the context

of the pilgrimage.

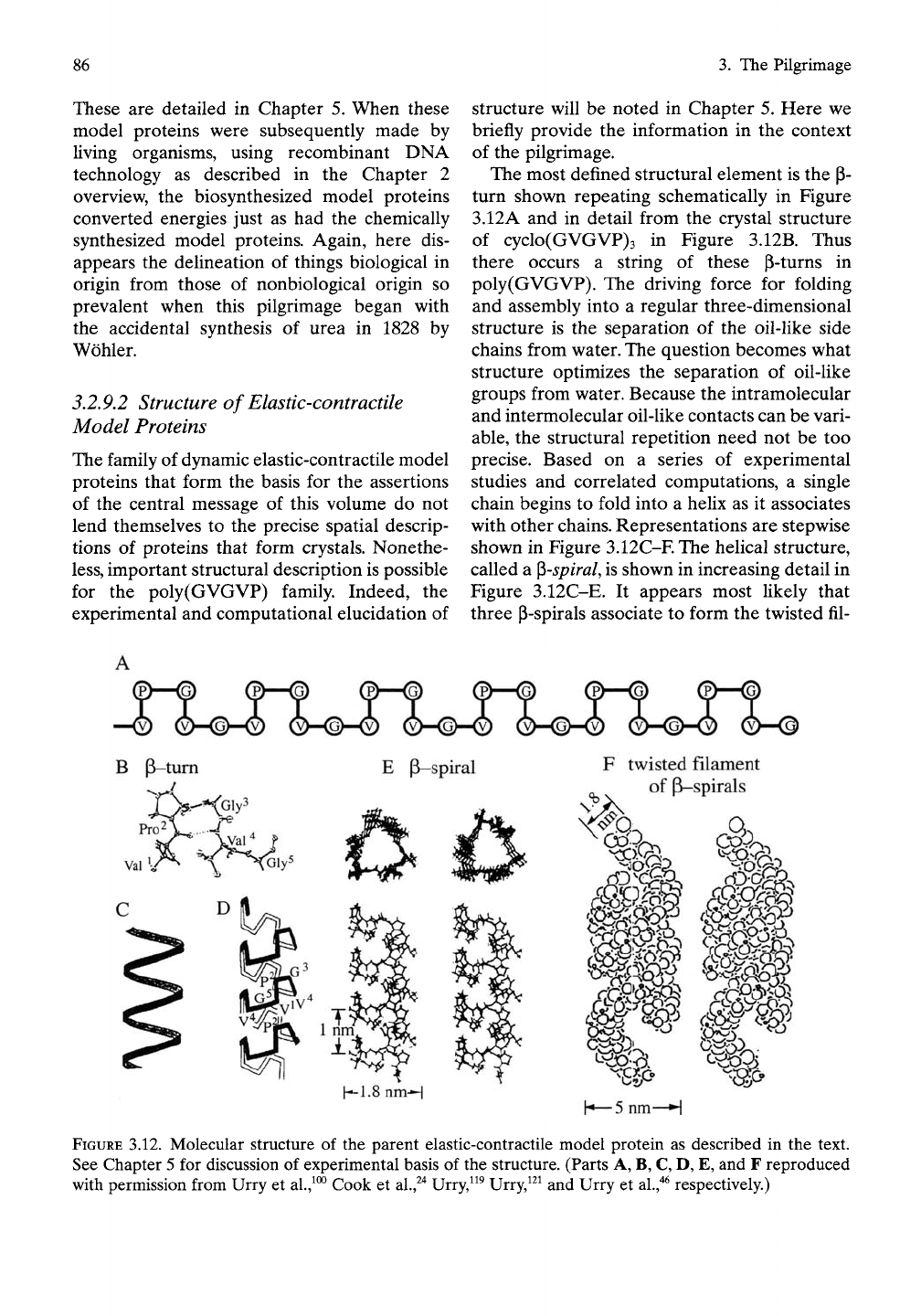

The most defined structural element is the p-

turn shown repeating schematically in Figure

3.12A and in detail from the crystal structure

of cyclo(GVGVP)3 in Figure 3.12B. Thus

there occurs a string of these P-turns in

poly(GVGVP). The driving force for folding

and assembly into a regular three-dimensional

structure is the separation of the oil-like side

chains from water. The question becomes what

structure optimizes the separation of oil-like

groups from water. Because the intramolecular

and intermolecular oil-like contacts can be vari-

able,

the structural repetition need not be too

precise. Based on a series of experimental

studies and correlated computations, a single

chain begins to fold into a helix as it associates

with other chains. Representations are stepwise

shown in Figure 3.12C-F. The helical structure,

called a ^spiral, is shown in increasing detail in

Figure 3.12C-E. It appears most likely that

three P-spirals associate to form the twisted fil-

(p)—<p)

®—^ (p—^ (S—(^ (p—-© ^>—©

—(& ©-^M^ ©-©-® ^-©-(^ ©-©-© ^-©-(^ ®—©

E P-spiral

F twisted filament

of P-spirals

FIGURE 3.12. Molecular structure of the parent elastic-contractile model protein as described in the text.

See Chapter 5 for discussion of experimental basis of the structure. (Parts A, B, C, D, E, and F reproduced

with permission from Urry et

al.,^°^

Cook et

al.,^"^

Urry,^^^ Urry,^^^ and Urry et

al.,"*^

respectively.)

3.2 Determination of Biological Structures and Their Syntheses

87

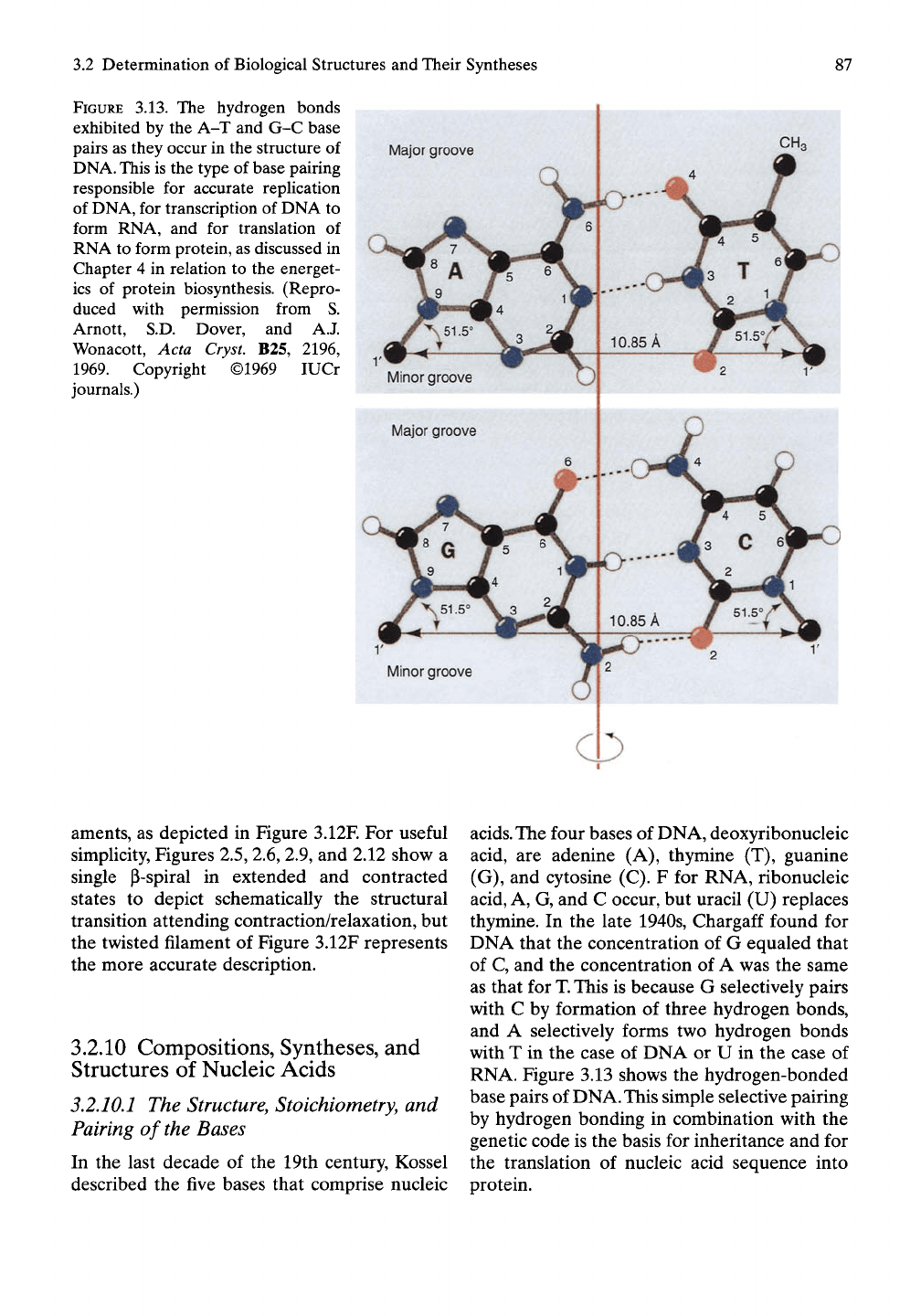

FIGURE 3.13. The hydrogen bonds

exhibited by the A-T and G-C base

pairs as they occur in the structure of

DNA.

This is the type of base pairing

responsible for accurate replication

of DNA, for transcription of DNA to

form RNA, and for translation of

RNA to form protein, as discussed in

Chapter 4 in relation to the energet-

ics of protein biosynthesis. (Repro-

duced with permission from S.

Arnott, S.D. Dover, and A.J.

Wonacott, Acta Cryst. B25, 2196,

1969.

Copyright ©1969 lUCr

journals.)

Major groove

aments, as depicted in Figure 3.12F. For useful

simplicity, Figures 2.5,2.6,2.9, and 2.12 show a

single p-spiral in extended and contracted

states to depict schematically the structural

transition attending contraction/relaxation, but

the twisted filament of Figure 3.12F represents

the more accurate description.

3.2.10 Compositions, Syntheses, and

Structures of Nucleic Acids

3.2.10.1 The Structure, Stoichiometry, and

Pairing of the Bases

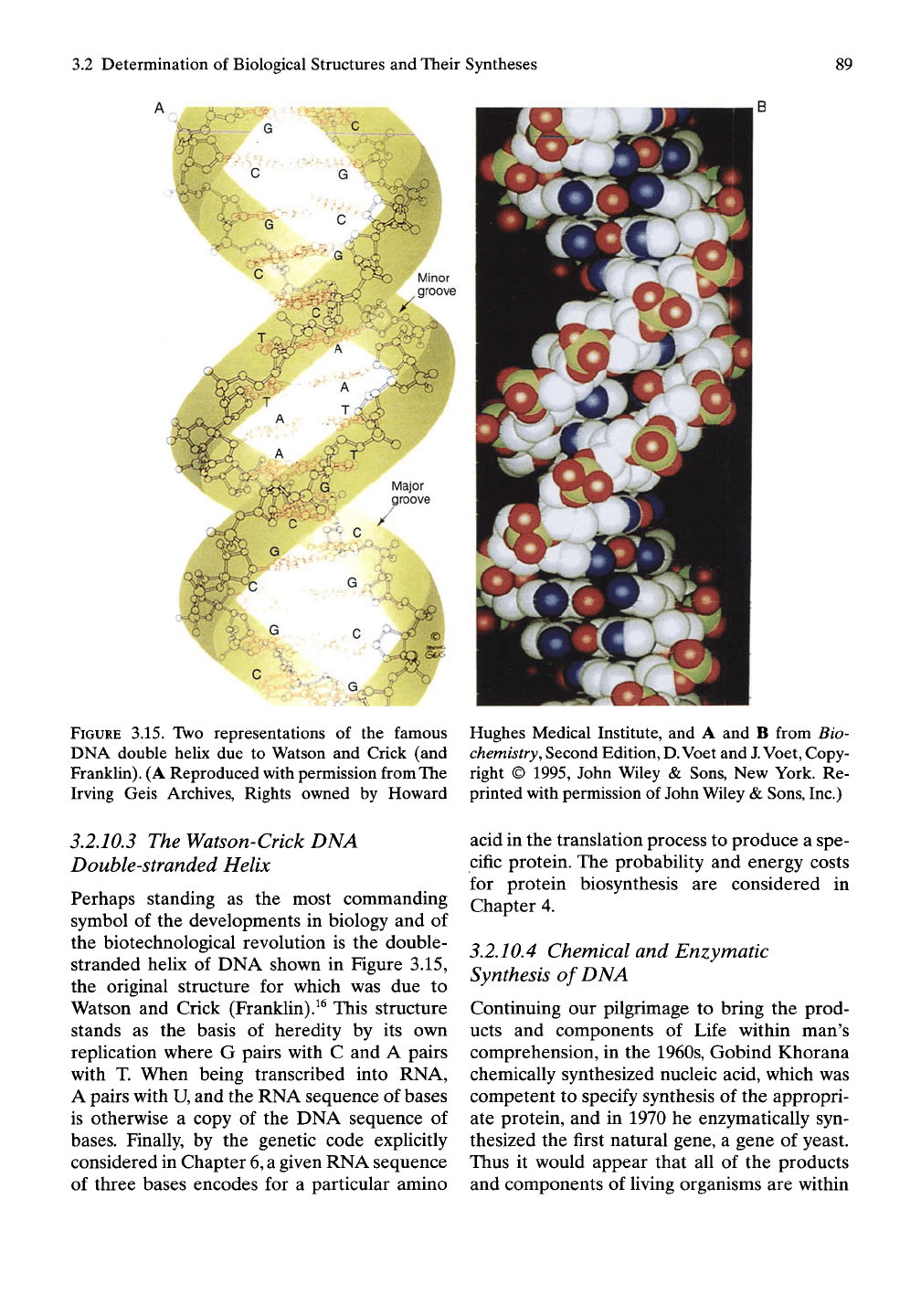

In the last decade of the 19th century, Kossel

described the five bases that comprise nucleic

acids.

The four bases of DNA, deoxyribonucleic

acid, are adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine

(G),

and cytosine (C). F for RNA, ribonucleic

acid. A, G, and C occur, but uracil (U) replaces

thymine. In the late 1940s, Chargaff found for

DNA that the concentration of G equaled that

of C, and the concentration of A was the same

as that for T. This is because G selectively pairs

with C by formation of three hydrogen bonds,

and A selectively forms two hydrogen bonds

with T in the case of DNA or U in the case of

RNA. Figure 3.13 shows the hydrogen-bonded

base pairs of DNA. This simple selective pairing

by hydrogen bonding in combination with the

genetic code is the basis for inheritance and for

the translation of nucleic acid sequence into

protein.

3.

The Pilgrimage

32.10,2 Sugar-Phosphate Backbone of

the Nucleic Acids

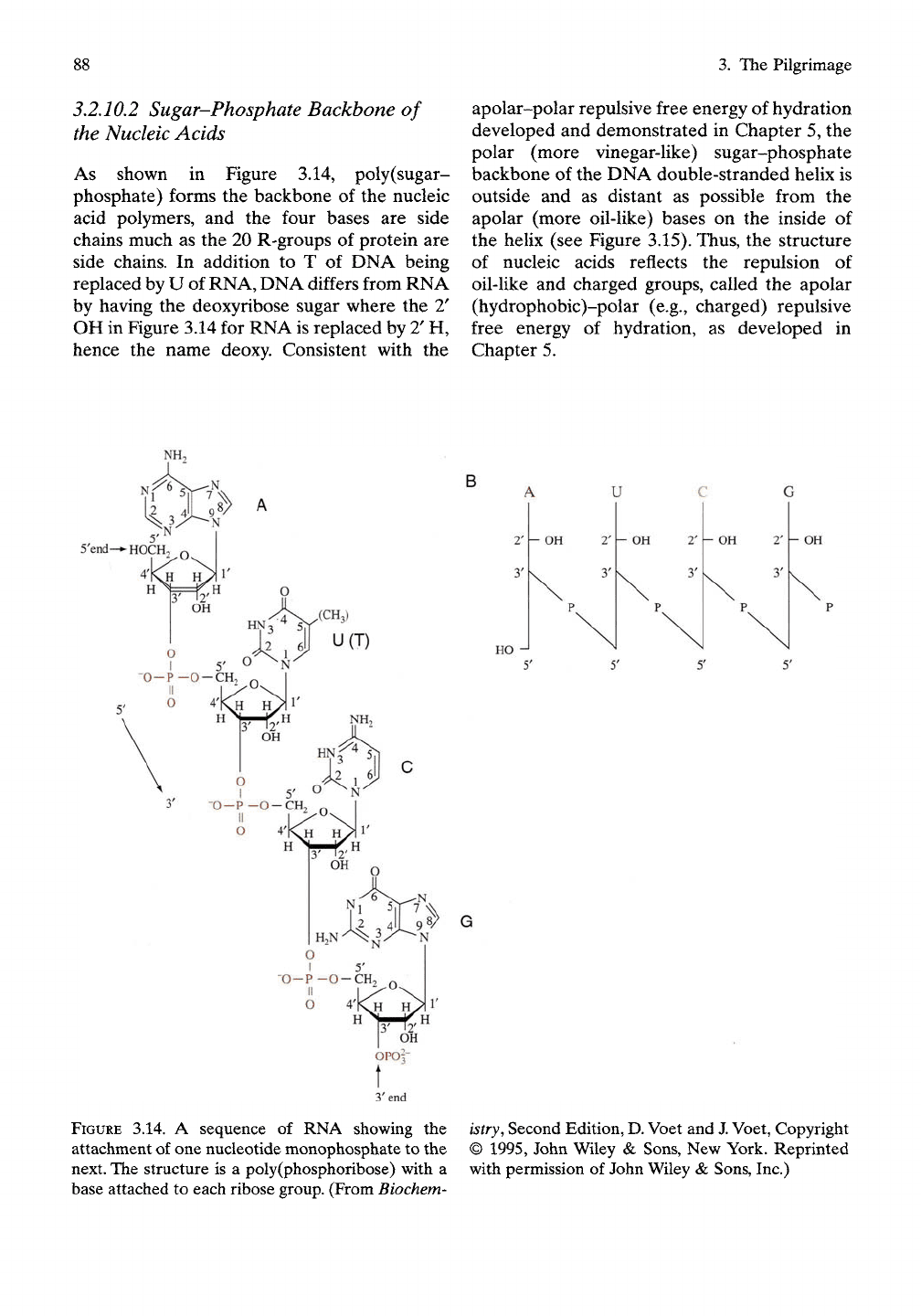

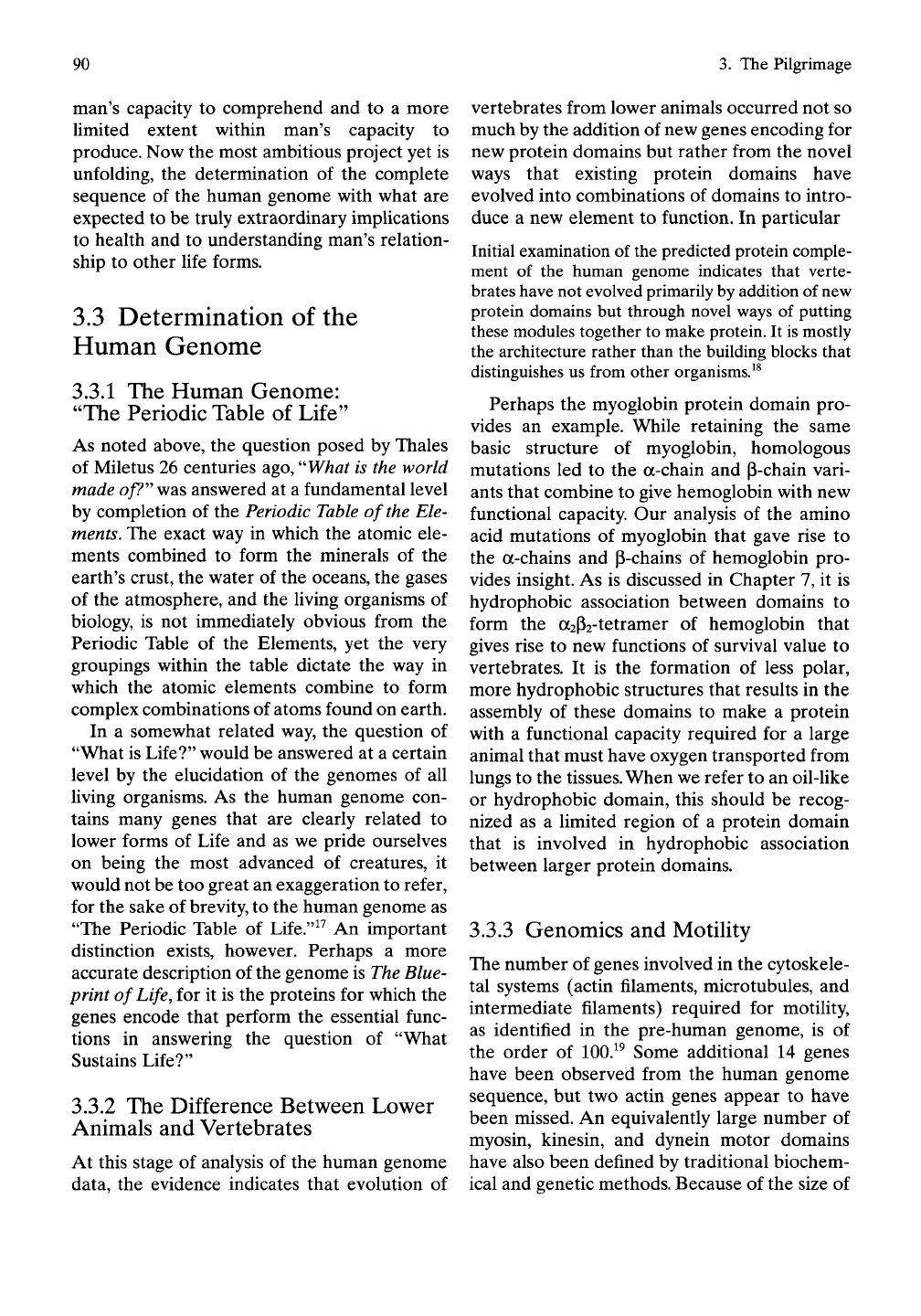

As shown in Figure 3.14, poly(sugar-

phosphate) forms the backbone of the nucleic

acid polymers, and the four bases are side

chains much as the 20 R-groups of protein are

side chains. In addition to T of DNA being

replaced by U of RNA, DNA differs from RNA

by having the deoxyribose sugar where the 2'

OH in Figure 3.14 for RNA is replaced by T H,

hence the name deoxy. Consistent with the

apolar-polar repulsive free energy of hydration

developed and demonstrated in Chapter 5, the

polar (more vinegar-like) sugar-phosphate

backbone of the DNA double-stranded helix is

outside and as distant as possible from the

apolar (more oil-like) bases on the inside of

the helix (see Figure 3.15). Thus, the structure

of nucleic acids reflects the repulsion of

oil-like and charged groups, called the apolar

(hydrophobic)-polar (e.g., charged) repulsive

free energy of hydration, as developed in

Chapter 5.

5'end-

,(CH3)

U(T)

3'end

FIGURE

3.14. A sequence of RNA showing the

attachment of one nucleotide monophosphate to the

next. The structure is a poly(phosphoribose) with a

base attached to each ribose group. (From Biochem-

U

C

2'

y

HO -

OH OH hOH OH

G

istry.

Second Edition,

D.

Voet and

J.

Voet, Copyright

© 1995, John Wiley & Sons, New York. Reprinted

with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

3.2 Determination of Biological Structures and Their Syntheses

A

89

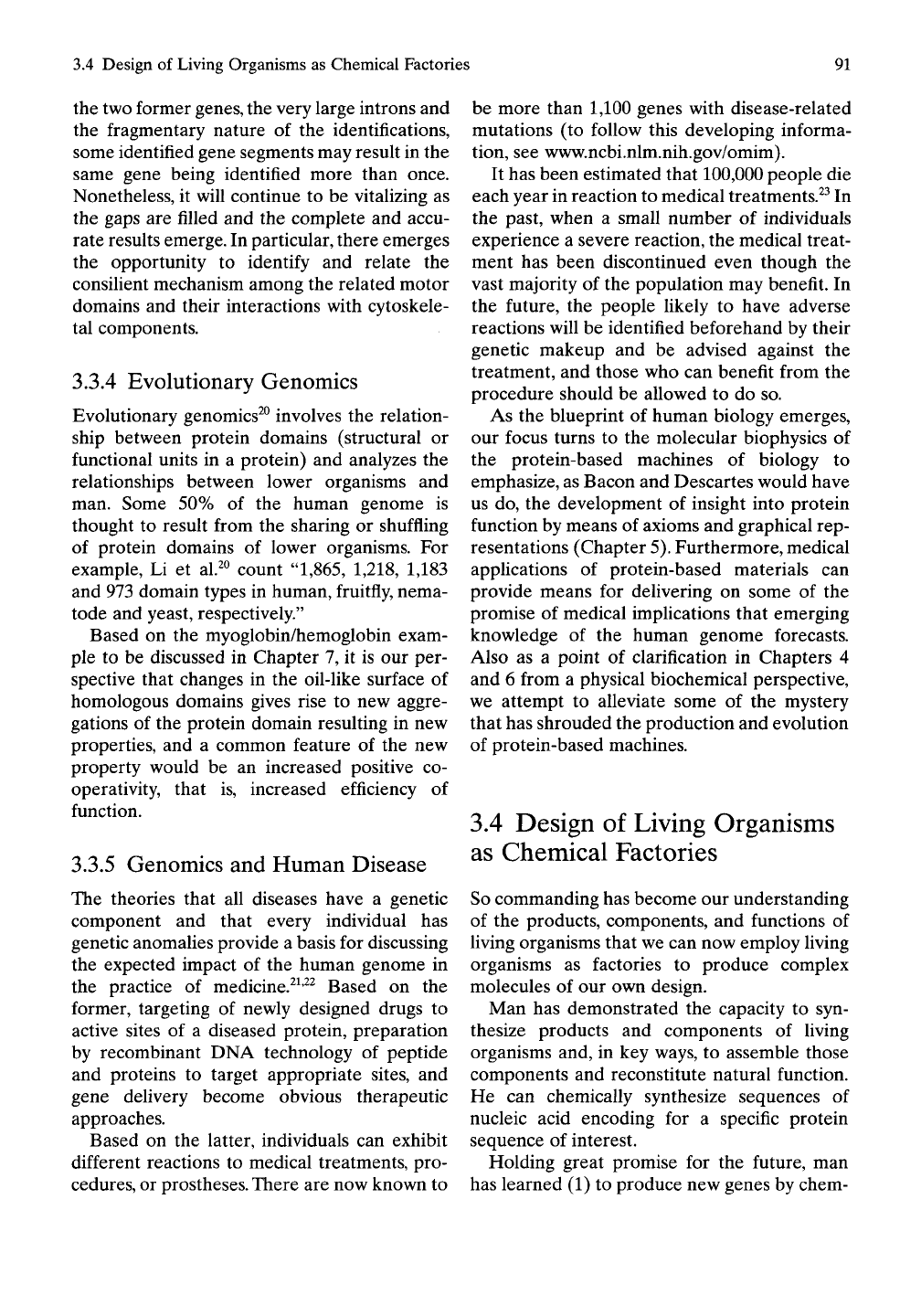

FIGURE

3.15. Two representations of the famous

DNA double helix due to Watson and Crick (and

Franklin). (A Reproduced with permission from The

Irving Geis Archives, Rights owned by Howard

Hughes Medical Institute, and A and B from Bio-

chemistry,

Second Edition,

D.

Voet and

J.

Voet,

Copy-

right © 1995, John Wiley & Sons, New York. Re-

printed with permission of John Wiley &

Sons,

Inc.)

3.2.10J The Watson-Crick DNA

Double-stranded Helix

Perhaps standing as the most commanding

symbol of the developments in biology and of

the biotechnological revolution is the double-

stranded helix of DNA shown in Figure 3.15,

the original structure for which was due to

Watson and Crick (Franklin).^^ This structure

stands as the basis of heredity by its own

replication where G pairs with C and A pairs

with T. When being transcribed into RNA,

A pairs with U, and the RNA sequence of bases

is otherwise a copy of the DNA sequence of

bases.

Finally, by the genetic code explicitly

considered in Chapter 6, a given RNA sequence

of three bases encodes for a particular amino

acid in the translation process to produce a spe-

cific protein. The probability and energy costs

for protein biosynthesis are considered in

Chapter 4.

3.2.10.4 Chemical and Enzymatic

Synthesis of DNA

Continuing our pilgrimage to bring the prod-

ucts and components of Life within man's

comprehension, in the 1960s, Gobind Khorana

chemically synthesized nucleic acid, which was

competent to specify synthesis of the appropri-

ate protein, and in 1970 he enzymatically syn-

thesized the first natural gene, a gene of yeast.

Thus it would appear that all of the products

and components of living organisms are within

90

3.

The Pilgrimage

man's capacity to comprehend and to a more

Umited extent within man's capacity to

produce. Now the most ambitious project yet is

unfolding, the determination of the complete

sequence of the human genome with what are

expected to be truly extraordinary implications

to health and to understanding man's relation-

ship to other life forms.

3.3 Determination of the

Human Genome

3.3.1 The Human Genome:

"The Periodic Table of Life"

As noted above, the question posed by Thales

of Miletus 26 centuries ago, "What is the world

made of?'' was answered at a fundamental level

by completion of the Periodic Table of the Ele-

ments. The exact way in which the atomic ele-

ments combined to form the minerals of the

earth's crust, the water of the oceans, the gases

of the atmosphere, and the living organisms of

biology, is not immediately obvious from the

Periodic Table of the Elements, yet the very

groupings within the table dictate the way in

which the atomic elements combine to form

complex combinations of atoms found on earth.

In a somewhat related way, the question of

"What is Life?" would be answered at a certain

level by the elucidation of the genomes of all

living organisms. As the human genome con-

tains many genes that are clearly related to

lower forms of Life and as we pride ourselves

on being the most advanced of creatures, it

would not be too great an exaggeration to refer,

for the sake of brevity, to the human genome as

"The Periodic Table of Life."^^ An important

distinction exists, however. Perhaps a more

accurate description of the genome is The Blue-

print of Life, for it is the proteins for which the

genes encode that perform the essential func-

tions in answering the question of "What

Sustains Life?"

3.3.2 The Difference Between Lower

Animals and Vertebrates

At this stage of analysis of the human genome

data, the evidence indicates that evolution of

vertebrates from lower animals occurred not so

much by the addition of new genes encoding for

new protein domains but rather from the novel

ways that existing protein domains have

evolved into combinations of domains to intro-

duce a new element to function. In particular

Initial examination of the predicted protein comple-

ment of the human genome indicates that verte-

brates have not evolved primarily by addition of new

protein domains but through novel ways of putting

these modules together to make protein. It is mostly

the architecture rather than the building blocks that

distinguishes us from other organisms. ^^

Perhaps the myoglobin protein domain pro-

vides an example. While retaining the same

basic structure of myoglobin, homologous

mutations led to the a-chain and (3-chain vari-

ants that combine to give hemoglobin with new

functional capacity. Our analysis of the amino

acid mutations of myoglobin that gave rise to

the a-chains and P-chains of hemoglobin pro-

vides insight. As is discussed in Chapter 7, it is

hydrophobic association between domains to

form the a2P2-tetramer of hemoglobin that

gives rise to new functions of survival value to

vertebrates. It is the formation of less polar,

more hydrophobic structures that results in the

assembly of these domains to make a protein

with a functional capacity required for a large

animal that must have oxygen transported from

lungs to the

tissues.

When we refer to an oil-like

or hydrophobic domain, this should be recog-

nized as a limited region of a protein domain

that is involved in hydrophobic association

between larger protein domains.

3.3.3 Genomics and Motility

The number of genes involved in the cytoskele-

tal systems (actin filaments, microtubules, and

intermediate filaments) required for motility,

as identified in the pre-human genome, is of

the order of 100.^^ Some additional 14 genes

have been observed from the human genome

sequence, but two actin genes appear to have

been missed. An equivalently large number of

myosin, kinesin, and dynein motor domains

have also been defined by traditional biochem-

ical and genetic methods. Because of the size of

3.4 Design of Living Organisms as Chemical Factories

91

the two former

genes,

the very large introns and

the fragmentary nature of the identifications,

some identified gene segments may result in the

same gene being identified more than once.

Nonetheless, it will continue to be vitalizing as

the gaps are filled and the complete and accu-

rate results emerge. In particular, there emerges

the opportunity to identify and relate the

consilient mechanism among the related motor

domains and their interactions with cytoskele-

tal components.

3.3.4 Evolutionary Genomics

Evolutionary genomics^^ involves the relation-

ship between protein domains (structural or

functional units in a protein) and analyzes the

relationships between lower organisms and

man. Some 50% of the human genome is

thought to result from the sharing or shuffling

of protein domains of lower organisms. For

example, Li et al.^^ count "1,865,

1,218,

1,183

and 973 domain types in human, fruitfly, nema-

tode and yeast, respectively."

Based on the myoglobin/hemoglobin exam-

ple to be discussed in Chapter 7, it is our per-

spective that changes in the oil-like surface of

homologous domains gives rise to new aggre-

gations of the protein domain resulting in new

properties, and a common feature of the new

property would be an increased positive co-

operativity, that is, increased efficiency of

function.

3.3.5 Genomics and Human Disease

The theories that all diseases have a genetic

component and that every individual has

genetic anomalies provide a basis for discussing

the expected impact of the human genome in

the practice of medicine.^^'^^ Based on the

former, targeting of newly designed drugs to

active sites of a diseased protein, preparation

by recombinant DNA technology of peptide

and proteins to target appropriate sites, and

gene delivery become obvious therapeutic

approaches.

Based on the latter, individuals can exhibit

different reactions to medical treatments, pro-

cedures, or

prostheses.

There are now known to

be more than 1,100 genes with disease-related

mutations (to follow this developing informa-

tion, see www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim).

It has been estimated that 100,000 people die

each year in reaction to medical treatments.^^ In

the past, when a small number of individuals

experience a severe reaction, the medical treat-

ment has been discontinued even though the

vast majority of the population may benefit. In

the future, the people likely to have adverse

reactions will be identified beforehand by their

genetic makeup and be advised against the

treatment, and those who can benefit from the

procedure should be allowed to do so.

As the blueprint of human biology emerges,

our focus turns to the molecular biophysics of

the protein-based machines of biology to

emphasize, as Bacon and Descartes would have

us do, the development of insight into protein

function by means of axioms and graphical rep-

resentations (Chapter

5).

Furthermore, medical

applications of protein-based materials can

provide means for delivering on some of the

promise of medical implications that emerging

knowledge of the human genome forecasts.

Also as a point of clarification in Chapters 4

and 6 from a physical biochemical perspective,

we attempt to alleviate some of the mystery

that has shrouded the production and evolution

of protein-based machines.

3.4 Design of Living Organisms

as Chemical Factories

So commanding has become our understanding

of the products, components, and functions of

living organisms that we can now employ living

organisms as factories to produce complex

molecules of our own design.

Man has demonstrated the capacity to syn-

thesize products and components of living

organisms and, in key ways, to assemble those

components and reconstitute natural function.

He can chemically synthesize sequences of

nucleic acid encoding for a specific protein

sequence of interest.

Holding great promise for the future, man

has learned (1) to produce new genes by chem-

92

3.

The Pilgrimage

ical synthesis of nucleic acids with base pairing

overlaps, (2) to use the renowned enzymatic

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to extend

and form double-stranded DNA, and (3) to use

the ligase enzyme to splice together large

synthetic gene segments. The synthetic genes

can be introduced into organisms in such a way

as to induce the organism to produce the spec-

ified protein. Man can genetically engineer

living organisms to produce not only proteins

natural to other organisms but also new pro-

teins of man's own design for functions that

evolution never called upon living organisms to

perform.

A few examples are discussed in Chapter 9

wherein the future will see the biosynthesis of

biodegradable protein-based thermoplastics,

materials to prevent postsurgical adhesions,

temporary functional scaffoldings to direct

tissue reconstruction, and drug delivery devices

for new drug release regimens.

Indeed, the period from Wohler's accidental

synthesis of urea in 1828 to the Biotechnologi-

cal Revolution of today presents a remarkable

pilgrimage with the potential for dramatic and

constructive consequences for individual health

and societal development.

References

1.

Our pilgrimage revisits highlights in the devel-

oping understanding of products and compo-

nents of living organisms and thereby provides

historical backdrop for the development of bio-

molecular machines and materials.

2.

D.J. Boorstin, The Seekers: The Story of Man's

Continuing Quest to Understand His

World.

Random House, New York,

1998,

p.

22.

3.

T.R. Malthus, An Essay on the

Principle

of

Pop-

ulation, London, 1798; rev. ed., 1803. Quotation

excerpted from "Darwin'' A Norton Critical

Edition, Third Edition, Selected and Edited by

Philip Appleman,

W.W.

Norton, New

York,

2001,

p.

39.

4.

J. Bronowski,

The

Ascent of

Man.

Little, Brown

and Company, Boston/Toronto, 1973.

5.

So attacked was Vesalius for departing from the

Galenist doctrine that he gave up his research on

anatomy for the practice of medicine only to

attempt

a

return in the year of

his

death at age 50.

6. Harvey counted Kings (James I and Charles I)

and distinguished contemporaries such as Sir

Francis Bacon among his patients. As a result of

publishing his unorthodox views of the circula-

tion of the blood, his prestigious practice is

reported to have suffered.

7.

Ionic ammonium cyanate, NH/»«»OCN~, con-

tains the four most common elements of living

matter, carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O),

and nitrogen (N). On heating, there is simply a

rearrangement of the atoms to result in urea,

H2NCONH2. This finding played a significant

role in the debate between mechanists and vital-

ist, a philosophical issue that little interested

Wohler.

8. The term

organic

as used here indicates "of bio-

logical origin." More currently the term organic

chemistry

has come to mean the chemistry of the

carbon atom.

9. The chemical structure of tartaric acid is

HOOC-HCOH-HOCH-COOH, which has two

carbon atoms with four different substituents,

that is, two centers of asymmetry. The natural

tartaric acid is dextrorotatory.

10.

A familiar use of the capacity to distinguish

plane-polarized light is found in the effective-

ness of Polaroid sunglasses. Sunlight scattered

from a road's surface, for example, is polarized

horizontally, and Polaroid sunglasses are

designed such that only vertically polarized light

passes through them and therefore the bright

light scattered from the road's surface does not

enter the eyes. If a dextro-rotatory solution of

tartaric acid or of sugar is placed in a tube and

the tube is placed in front of the polaroid glasses,

the scattered light from the surface of the road

that passes through the tube will also pass

through the sun glasses unless the sun glasses are

rotated clockwise. At the correct amount of

clockwise rotation, the tube becomes dark, and

more of the scattered light from the surface of

the road passes through the portion of the

sunglasses that surround the tube.

11.

L. Pasteur, "On the Molecular Asymmetry of

Natural Organic Products." In Lecons de Chimie

professees en 1860. Chemical Society of Paris,

Paris,

1861. George Stewart and Co., printers,

Edinburgh and London.

12.

Because of his extraordinary knowledge of

chemistry, Fischer was placed in charge of orga-

nizing chemical production in Germany during

the First World War. Among the many mis-

fortunes of that war were the combat deaths of

his two sons. So distraught was Fischer by his

circumstances that he ended his own life shortly

thereafter—in 1919.

References 93

13.

D. Voet and J. Voet, "Electron Transport and

Oxidative Phosphorylation." In Biochemistry,

Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York,

1995.

14.

In the usual manner the Katsoyannis publication

of their work (/. Am. Chem. Soc,

85,

2863,1963)

acknowledged at the end of the publication the

support of the U. S. Public Health Service,

National Institute of Arthritis and MetaboHc

Dis-

eases.

Interestingly,

Niu

and coworkers gave their

acknowledgments in the Introductory Remarks

with the statements "by holding aloft the great

red banner of Mao Tse-tungs's thinking" and

The total chemical synthesis of insulin is a piece

of work which stems directly from the big leap

forward movement. In 1958, when the move-

ment had attained the stage of unbounded

enthusiasm for achievements,

we

took upon our-

selves the task of making synthetic insulin as the

first protein ever to be synthesized, an achieve-

ment which we hope to accomplish in a short

time to serve as a contribution to the scientific

progress of our mother country and also as an

expression of revolutionary initiative. (Kexue

Tongbao,

17,

241,1966)

15.

C.S. Roy, "The Elastic Properties of the Arterial

Wall."

/. Physiol., 3,125-159,1880.

16.

ID. Watson and EH.C. Crick, "Molecular

Structure of Nucleic Acids." Nature, 111, 131-

738,1953.

17.

S. Paabo, "The Human Genome and Our View

of Ourselves."

Science,

291 (February 16), 1219-

1220,2001.

18.

Editorial Comments, Science, 291, 1218,

2001.

19.

T.D. Pollard, "Genomics, the Cytoskeleton and

MotiUty." Nature, 409, 843-845, 2001.

20.

W-H. Li, Z. Gu, H. Wang, and A. Nekutenko,

"Evolutionary Analysis of the Human Genome."

Nature,

409, 847-849,

2001.

21.

L. Peltonen and V.A. McKusick, "Dissecting

Human Disease in the Postgenomic Era."

Science,

291,1224-1229,2001.

22.

G. Jimenez-Sanchez, B. Childs, and D. Valle,

"Human Disease Genes." Nature, 409, 853-855,

2001.

23.

D.

Drell and

A.

Adamson, "Fast Forward to 2020:

What to Expect in Molecular Medicine." In The

Human Genome Project Information: Medicine.

June,

13, 2002 (from online magazine TNTY

Futures).

Likelihood of Life's Protein Machines:

Extravagant in Construction Yet

Efficient in Function

4.1 Introduction

A protein with its specified sequence, where

each position is filled by but 1 of 20 different

amino acid residues, represents an extremely

improbable construct. Perhaps in part because

of this improbability, searches for under-

standing have reasonably considered far-

from-equilibrium conditions and addressed cir-

cumstances whereby order may appear out

of chaos. On the other hand, biochemists with

painstaking commitment have worked their

way down to the component processes of DNA

replication, of transcription of DNA into RNA,

and of translation of RNA into protein

sequence. They dissected each constituent

process into its scores of energy-requiring reac-

tions,

assembled these reactions to provide a

compelling description of each component, and

emerged with a stunning tale of heredity and

protein biosynthesis. Biology's story of protein

biosynthesis is one of such elegant detail that,

no matter how brilliant the mind, it could not

have been derived otherwise. Accordingly, there

is now little mystery in how a protein of speci-

fied sequence can come into being; it simply

requires adequate energy. In fact, the details of

protein biosynthesis reveal an extravagant

process requiring extraordinary amounts of

energy.

We must yet, of course, admit mystery in

how all of those integrated and interdependent

molecular machines came into being in forma-

tion of the first cell with the capacity to synthe-

size protein of specified sequence.

In this chapter we briefly note the improba-

bility of a protein comprised of 20 different

amino acids in specified sequence. Then we step

through the details whereby a protein of spec-

ified sequence comes into being, and, like the

accountant, sum up the cost in terms of the

biological energy currency, adenosine triphos-

phate (ATP), that is, in terms of the number of

ATP molecules consumed in the production of

a protein of unique sequence. Such an essen-

tially ordinary exercise requires inclusion in

this book in order to remove unnecessary

mystery of protein production, to provide an

example whereby molecular machines utilize

energy to produce biological structure, and to

place in perspective the ease with which new

protein-based machines evolve when function-

ing by the consilient mechanism.

4.2 Improbability of a Unique

Protein Sequence

4.2.1 Consideration of a Small 100

Residue Protein

Twenty different amino acid residues become

incorporated into protein. The question may be

stated as, what is the probability of occurrence

of even a small protein of 100 amino acid

residues of specified sequence? The calculation

can be quite simple. For equal availability of all

20 amino acids, the probability of any 1 of the

20 amino acid residues occurring in a single

position is (1/20). The probability for a com-

94