Sussex R., Cubberley P. The Slavic Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The vowel /a

¨

/ may occur also after velars: CS-Slk kamen

ˇ

‘stone’,

Cen-Slk ka

¨

men

ˇ

.

Final /l/ in l-participles becomes [u9], a feature only colloquial in

the standard: CS-Slk dal ‘gave’ [-al], Cen-Slk [-au9].

3. Eastern

Stress is penultimate, as in Polish, and phonemic quantity is lost,

as in Polish and East Slavic. With the loss of quantity goes the

loss of the Slovak Rhythmic Law.

Vocalic /l

˚

/and/r

˚

/, which can be both short and long in standard

Slovak, are not found in E-Slk, as in Polish and East Slavic. In their

place are ‘vowel þ liquid’ (more rarely ‘liquid þ vowel’) sequences:

(53) CS-Slk vlk [v

˙

lk] ‘wolf’ E-Slk vil’k/vel’k (Pol wilk )

CS-Slk vrch [v

˙

rx] ‘top’ E-Slk verch (Pol wierzch,Ukrverx).

Proto-Slavic e˛, when short, becomes /e/, as in South Slavic:

CS-Slk ma

¨

so ‘meat’, E-Slk meso (Sln meso

´

, B/C/S me

&

so).

The palatal stops /t’/ and /d’/ of the standard become hard dental

affricates /c/, /dz/ as in W-Slk (above), though here we may see a

transition to Belarusian’s affrication (3.2.2.1, 10.3.1). Some areas

have instead post-alveolar /c

ˇ

dzˇ /, closer to Polish (c

´

dz´ ).

/s/ and /z/ are palatalized before front vowels, as in Polish: CS-Slk

seno ‘hay’, E-Slk s

´

eno; CS-Slk zima ‘winter’, E-Slk z

´

ima.

10.4.4.2 Morphology and morphophonology

1. Western

Nouns

Hard nominative singular neuter nouns have -o against CS-Slk

-e: CS-Slk vajce ‘egg’, W-Slk vajco.

Soft nominative singular neuter nouns have -e

´

/-ı

´

against CS-Slk

-ie: CS-Slk zbozˇie ‘corn, grain’, W-Slk zbozˇe

´

/zbozˇı

´

.

Nominative plural masculine animate nouns have -e

´

/-ie/-ie

´

against CS-Slk -ia: CS-Slk l’udia ‘people’, W-Slk lude

´

/lud’ie/

lud’ie

´

.

Genitive singular masculine a-stems have -i against CS-Slk -u:

CS-Slk gazdu ‘farmer’ [GenSg], W-Slk gazdi.

Nominal

The instrumental singular feminine has -u/-u

´

against CS-Slk -ou:

CS-Slk s tou dobrou zˇenou ‘with that good woman’, W-Slk stu

´

dobru

´

zˇenu

´

.

10.4 West Slavic 539

Adjectives

The soft type have ‘hard’ endings, in -e

´

ho etc., against CS-Slk

-ieho etc.: CS-Slk cudzieho ‘foreign’ [GenSg], W-Slk cudze

´

ho.

The locative singular masculine/neuter has -e

´

m against CS-Slk

-om: CS-Slk dobrom ‘good’, W-Slk dobre

´

m.

Verbs

The infinitive has hard -t against CS-Slk -t’. CS-Slk vedet’ ‘to

know’, W-Slk vediet.

The present/infinitive theme has short -e- against CS-Slk -ie:

CS-Slk nesiem ‘I carry’, W-Slk nesem.

‘Not to be’ is neni som, etc. against CS-Slk nie som ...

2. Central

Adjectives

The nominative singular neuter has -uo (o

ˆ

)/-o against CS-Slk -e

´

:

CS-Slk dobre

´

‘good’, W-Slk dobruo/dobro.

Verbs

‘They are’ is sa against CS-Slk su

´

.

3. Eastern

Nouns

Genitive singular masculine a-stems have -i against CS-Slk -u,as

in W-Slk (above).

Also like W-Slk, hard nominative singular neuter nouns have

-o against CS-Slk -e (above).

The instrumental singular masculine/neuter has -om against

CS-Slk -em: CS- Slk bratem ‘brother’ [InstrSg], E-Slk bratom.

The genitive/locative plural of all genders has -och against CS-Slk

-ov/-ø, -och/a

´

ch:

(54) ‘brother’, ‘town’ [Gen/LocPl]:

CS-Slk bratov [GenPl], bratoch [LocPl]

E-Slk bratoch [Gen=LocPl]

CS-Slk miest [GenPl], mesta

´

ch [LocPl]

E-Slk mestoch [Gen=LocPl]

The dative plural of all genders has -om against CS-Slk Masc

only:

(55) ‘woman’, ‘town’ [DatPl]:

CS-Slk zˇena

´

m, mesta

´

m E-Slk zˇenom, mestom

540 10. Dialects

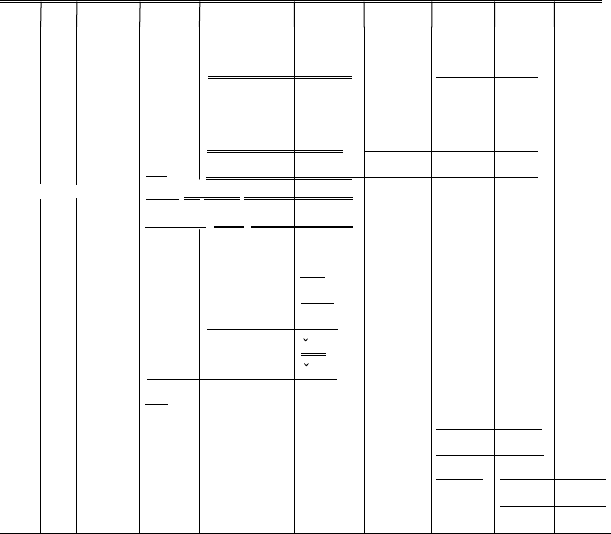

Table 10.11. Dialects of Slovak

CS-Slk Cen-Slk W-Slk E-Slk

Phonology

Vowels

PSl jers e, a, o ¼ CS e e

PSl e˛ a

¨

,a,ia ¼ CS a e

vocalic liquids þ¼CS ¼ CS –

diphthongs ie, uo ¼ CS ı

´

/e

´

,u´ /o

´

i, u

PSl o

&

rC-, o

&

lC- raC-, laC- ¼ CS roC-, loC- roC-, loC-

Consonants

PSl tl dl tl, dl l ¼ CS ¼ CS

/t’ d’/ t’, d’ ¼ CS ¼ CS c, dz

/s z/ before front V s, z ¼ CS ¼ CS s

´

,z´

PSl stj etc. s

ˇ

t’ ¼ CS s

ˇ

c

ˇ

s

ˇ

c

ˇ

/l/ and /l’/ þ¼CS – ¼ CS

final /v/ u

˘

¼ CS f f

gemination – ¼ CS þ¼CS

Suprasegmentals

stress initial ¼ CS ¼ CS penult

phonemic quantity þ¼CS ¼ CS –

Rhythmic Law þ¼CS – –

Morphology

Nouns

NomSg Neut e ¼ CS o o

NomSg Neut -j ie ¼ CS e

´

/ı

´

e

NomPl MascAnim ia ¼ CS e

´

/ie/ie

´

i/e/ove

GenSg Masc a-stems u ¼ CS i i

InstrSg Masc/Neut em ¼ CS ¼ CS om

GenPl all M ov, N ø ¼ CS ¼ CS och

LocPl all M och, N a

´

ch ¼ CS ¼ CS och

DatPl all M om, N a

´

m ¼ CS ¼ CS om

Adjectives

Soft type ie-ho e

´

/ie/i-ho e

´

-ho e-ho

NomSg Neut e

´

o/o

´

/uo e

´

e

NomPl Poss Anim i, Inan e ¼ CS ¼ CS o

LocSg Masc/Neut om ¼ CS e

´

mim

Nouns, adjectives and pronouns

InstrSgFem ou ¼ CS u/u´ u

Verbs

Inf t’ ¼ CS t ¼ CS

1Pl Pres m ¼ CS ¼ CS me

Pres/Inf theme ie ¼ CS e e

‘be’ l-participle bol- ¼ CS ¼ CS bul-

‘they are’ su

´

sa ¼ CS sa/su

‘not to be’ nie som ... ¼ CS neni som ... n

ˇ

e som ...

10.4 West Slavic 541

Adjectives

The locative singular masculine/neuter has -im against CS-Slk

-om (and W-Slk -e

´

m, above): CS-Slk dobrom ‘good’, E-Slk

dobrim.

The nominative plural of possessive pronouns and adjectives of

all genders has -o against CS-Slk -i/-e: CS-Slk vas

ˇ

i deti ‘your

children’, E-Slk vas

ˇ

o dzeci.

Verbs

The 1 Person plural present has -me against CS-Slk -m: CS-Slk

nesiem ‘we carry’, E-Slk n

ˇ

es

´

eme.

NW NE

(Est) C-Rus

(Lith) (Lith) (Lith) (Latv) C-Rus C-Rus

Polab P-New Maz SW-Bel

SW-Bel

C-Bel

C-Bel

NE Bel S-Rus

S-Rus

S-Rus

S-Rus

S-Rus

S-Rus

C-Rus

(Germ) P-New S-Kash Maz

LSorb P-New Maz SW-Bel C-Bel

USorb P-New N-Ukr N-Ukr

(Germ) P-New SW-Ukr SE-Ukr

W-/Cen-/E-Slk

W-/Cen-/E-Slk

SW-Ukr

SW-Ukr

SE-Ukr

Boh C-Mor E-Mor SE-Ukr S-Rus

(Germ) (Austr) (Austr/Hung) (Hung)

(Austr: Koroš) Štaj Pan (Hung)

(Ital) Prim Štaj Kajk E-Herc Šum-V (Rom)

(Rom)

(Ital) Prim Dol Kajk E-Herc Šum-V

Notr Dol Cak E-Herc Šum-V

Notr

Notr

Notr

Kajk/Cak

E-Herc Kos-R

Ik

Ik E-Herc Kos-Res Torlak W-Blg

W-Blg

W-Blg

W-Blg

E-Blg

E-Blg

E-Blg

Zeta Kos-Res

(Alb) Torlak

(Alb) W-Mac SE-Blg

SE-Blg

C-Mac E-Mac

E-Mac

W-Blg

(Gr) (Gr) (Gr)

SW SE

N-Rus

N-Kash(G)

(G)

(G)

Sil

Sil

Lach

(Austr)

(Rom)

Wielk

Gor

Rovt

Cz-New Boh/Cz-new

Mal

∼

Mal

∼

Figure 10.1 Slavic dialects: contacts in diagrammatic form Geographical layout:

Columns ¼ north to south; Rows ¼ west to east N ¼ north; S ¼ south; E ¼ east; W ¼ west;

C ¼ central; others as in text or Appendix A. ‘New’ ¼ areas of new mixed dialects since 1945;

brackets ¼ adjacent countries (G ¼ Germ). Single underline: transitions across languages

within major groups (vertically or horizontally). Double underline: transitions across major

groups ('')

542 10. Dialects

‘Not to be’ is n

ˇ

e som ... against CS-Slk nie som ... (/e/ for /ie/).

‘They are’ is both sa and su against CS-Slk su

´

.

The ‘be’ l-participle has the stem bul- against CS-Slk bol-

(cf. Ukr bul-).

10.4.4.3 Lexical

‘What?’ is co (the common West Slavic form) in E-Slk, against CS-Slk, Cen-Slk and

W-Slk c

ˇo

(cf. C

ˇ

ak c

ˇa

).

In summary, key features of the dialects are shown in table 10.11.

10.5 Dialects: summary

The interconnections and transitions between the languages and dialects are shown

diagrammatically in figure 10.1.

10.5 Summary 543

11

Sociolinguistic issues

11.1 The sociolinguistics of the Slavic languages

With the exception of language standardization and regional variants (chapter 10),

the sociolinguistics of the Slavic languages has been under-researched. Much remains

to be done in the area of sociolects, for instance, except in so far as they overlap with

questions of the national language, language planning, language in education, corpus

planning and what the Russians call kul

0

tu

´

ra re

´

c

ˇ

i – the ‘culture of (good) speech’.

Raskin (1978) regarded this deficiency under Communism as mainly ideological:

a classless society is difficult to reconcile with sociolectal variation, and attempts

to work out a genuinely Marxist–Leninist philosophy of language have so far failed

to solve this question – though investigations like the Soviet Russian Russkij jazyk i

sovetskoe obs

ˇ

c

ˇ

estvo (Panov, 1968; Krysin, 1974; 11.3.1) provided a strong empirical

platform for socially correlated studies of language variation. The after-effects of

these problems of ideology and scholarship help to explain the uneven state of socio-

linguistics in the modern Slavic languages (Brang, Zu

¨

llig and Brang, 1981). Since the

decline of Communism this field has become a major growth area of research

(Cooper, 1989) in fields like colloquial language (Patton, 1988), political correctness

(Short, 1996), culture-marginal slangs (Skachinsky, 1972), graffiti (Bushnell, 1990)

and gay language (Kozlovskij, 1986), which were areas of scholarship not encouraged

at the official level under Communism. It is still too early to evaluate how lasting is the

linguistic effect of Communism, but we can begin to appreciate how the modern

languages are reinventing themselves in their new globalized context.

11.2 Language definition and autonomy

11.2.1 Status and criteria

A variety of socio-cultural criteria complement the diachronic analysis of the

emergence of the Slavic national languages (chapter 2, especially 2.5). Picchio

544

(1984) identifies two central factors in determining language-hood: dignitas and

norma. These criteria correspond approximately to ‘‘status’’ and ‘‘standardiza-

tion’’. A language needs to be valued, especially by its speakers but also by out-

siders. It needs a description which defines it as distinct from others (Kloss’s

abstand), and to capture its internal consistency (Garvin, 1959; Issatschenko, 1975).

It should also cover the required social and functional roles (Kloss’s ausbau [1952]),

and should be stable enough to constitute a defined and constant core around

which its identity is defined and maintained. But, at the same time, it should exhibit

‘‘flexible stability’’ (Cz pr

˚

uzˇna

´

stabilita), a concept developed by linguists of the

Prague School (Havra

´

nek and Weingart, 1932; Havra

´

nek, 1936, 1963; Mathesius,

1947), allowing it to adapt to changing circumstances, social needs and commu-

nicative demands. We can augment the criteria presented in Stewart (1968) to

arrive at the following characteristics.

1. Standardization. A standardized language is formally unified, and

culturally unifying. The lack of a standardized variant has prevented

Kashubian from qualifying as a separate language. Standardization

needs to be exemplified in grammars, dictionaries, style and usage

guides, and orthoepy, and it needs to be realized in written and spoken

usage, and in policy, the media and education.

2. Autonomy (abstand). Languages need to assert their formal autonomy

(distinctiveness) and cultural autonomy (independence). The auto-

nomy of two modern Slavic languages is under some threat: Belarusian

(2.3.3), which feels the cultural pressure of Russian; and, to a lesser

degree, Macedonian (2.2.3), though here internal loyalty to the lan-

guage counterbalances the Bulgarian perception that Macedonian is a

western dialect of Bulgarian. Of the rest, Bosnian (2.2.4.3) is still estab-

lishing and defining its autonomy; Croatian (2.2.4.2) is distancing itself

from Serbian; and Ukrainian (2.3.2), about which there were some fears

under Russian-dominated practices in the USSR, is looking increasingly

secure, though not necessarily stable or homogeneous (Pugh and Press,

1999: introduction).

Among the means of maintaining, safeguarding and promoting

autonomy are Lencek’s (1982) criteria of ‘ ‘Slavization’’ and ‘‘vernacul-

arization’ ’ (9.2.4). Lexical purification is one of the most obvious signs

of this policy, particularly since it lends itself to direct management more

than other aspects of language planning and policy.

3. Historicity. Historicity is concerned with early linguistic monuments

and continuous cultural development. Authentic historicity is an

11.2 Language definition and autonomy 545

advantage to a language-culture, for instance in the Classical lan-

guages. Languages lacking historicity may try to establish claims to

historicity in order to avoid the appearance of an upstart culture-

come-lately. Competing claims for historicity can cause tension:

between Bulgarian and Macedonian over Old Church Slavonic cul-

ture; and between Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian for old East

Slavic culture. Lencek’s (1982) criterion of ‘‘archaization’’, the con-

scious and directed evocation of historical models, is an expression of

historicity. It is seen in the revival of the Czech, Sorbian and Slovenian

literary languages during the Romantic era. It also describes, in a

rather different way, the strong continuing presence of Church

Slavonic elements in modern Russian. A recent re-analysis of the

history of Slovak (Lifanov, 2001) aims to establish a deeper historicity

vis-a

`

-vis Czech than has hitherto been accepted.

4. Ausbau is the way in which a language develops to fulfil society’s

functional, cultural and social roles. Languages which lack a full

range of communicative roles are thereby restricted. A common restric-

tion is liturgical, a role filled by Latin or Church Slavonic for most of the

history of the Slavic literary languages. Another was political: in the

former Czechoslovakia, for instance, German occupied many public

roles until 1918. Belarusian is currently constrained by the parallel use

of Russian in some public roles, including administration and intellec-

tual life. Kashubian has little presence at the intellectual, journalistic or

administrative level, and so is functioning more as a language of local

solidarity, folklore and literature. The establishment of a full range of

styles in Macedonian after 1944 replaced functions which had been

fulfilled by Bulgarian, Serbian or Serbo-Croatian. A similar task now

faces Bosnian vis-a

`

-vis Croatian and Serbian.

5. Vitality. A vital language has sufficient numbers of speakers to defend

itself against cultural invasion or dilution. A vital language is used in all

contexts and walks of life, and has first claim for all relevant language

roles. Sorbian shows a genuine lack of vitality, since its numbers are

declining and the dominating German culture fulfils many language

roles, especially in non-spoken contexts. And Belarusian has long been

lacking in vitality in its interaction with the Russian language.

6. Prestige. Prestige may be based on an awareness of a standardized

norm, autonomy, historicity or vitality. It may also involve loyalty

and pride, and a cultural self-awareness. Prestige is of fundamental

importance to the survival of languages in e

´

migre

´

communities. It has

546 11. Sociolinguistics

also played a vital part in the survival of the less populous Slavic

languages – especially Sorbian, Macedonian and Slovenian – and in

the maintenance of larger languages like Bulgarian, Polish, Czech and

Ukrainian through periods of foreign invasion and domination.

Prestige can also be enhanced by status planning and institutionaliza-

tion, the use of the language in public life (including administrative

functions, for instance in the chancery language of the East Slavs).

7. Monocentricity vs pluricentricity. Most Slavic languages are typically

monocentric, with a single, well-defined monolithic standard. But

languages like English, French and German (Clyne, 1991a,b;

Clyne ed., 1991) have multiple standards, depending on their geogra-

phical dispersion. Within Slavic, B/C/S (Brozovic

´

, 1991) is a stereo-

typical case of a pluricentric language, and moreover one established

by political agreement (2.2.4.1). A contrasting example is that of

Macedonian (Tomic

´

, 1991), where the failure to establish a pluricentric

language in collaboration with Bulgarian contributed to the abstand

formation of a new Macedonian literary language. A similar set of

circumstances contributed to the emergence of Slovak vis-a

`

-vis Czech.

The notion of pluricentricity also offers possibilities for the study of

other Slavic literary languages, particularly those where there have

been competing centres and standards during the emergence and

establishment of the national language. Here we find the Kiev

Moscow, and later Moscow St. Petersburg dichotomy in Russian;

western eastern tensions in Ukrainian; the Great Poland and Little

Poland elements in Polish, as well as the Kashubian Polish dichot-

omy; Upper and Lower Carniolan variants in Slovenian; and western

eastern tensions in Bulgarian recensions of Church Slavonic and in the

dialectal input between Ta

˘

rnovo and Sofia in the emergence of

Contemporary Standard Bulgarian. The dichotomy between Upper

and Lower Sorbian also lends itself to pluricentric interpretation.

Whereas Lower Sorbian may have enough typological properties to

warrant status as a separate language, the sociolinguistics of its current

position allow us to interpret Upper and Lower Sorbian as the two foci

of a single pluricentric language.

11.2.2 Standardization

In contrast to Schleicher’s view of languages as organic organisms (organische

Naturk

¨

orper) (Robins, 1967: 196, n. 73), which should be left to develop according

11.2 Language definition and autonomy 547

to their own dynamics, the Slavs overtly manage their languages through legisla-

tion and standardization. Without such language engineering the contemporary

languages would look very different. Arguably, some might not have survived to

modern times.

In the Slavic countries education and the media are highly centralized, and there

are Language Institutes of the Academies of Science in each country, one for each

language, with printing houses and journals whose specific concern is the culture,

promotion and defence of the native tongue. Even before the political disintegra-

tions of 1991–1992, there were two such academies in Czechoslovakia: one in

Prague for Czech; and one in Bratislava for Slovak. In Yugoslavia there were

four: in Ljubljana for Slovenian; in Zagreb for the Croatian variant of Serbo-

Croatian; in Belgrade for the Serbian variant; and in Skopje for Macedonian. In the

German Democratic Republic, in spite of the numerical domination of German,

the Academy in Berlin included an ‘Institut fu

¨

r sorbische Volksforschung’, and a

new Sorbian Institute (‘Serbski Institut’) opened in Bautzen in 1992. These lan-

guage institutes continue in the new autonomous states. They make policy, and

publicize, implement and monitor decisions about the national language. In this

way they can bring about a degree of uniformity and top-down direction which is

impossible for contemporary English. Historically speaking, the convention of

language legislation in orthography, grammar and lexis (through either church,

or state, or both) influenced the formation and standardization of all the Slavic

literary languages. In some cases, it was precisely the official legislating institutions,

together with institutions devoted to the promotion of the national language and

culture, which were among the most effective influences in promoting the new

literary languages, for instance the various nineteenth-century Matice (language

and culture institutes, often with strong nationalist missions grounded in ethnology

and folklore (Herrity, 1973) ).

The acceptance of a language as part of a constitution or national language

policy is a powerful way of reinforcing its standing, defending it against the

language of military or cultural invaders, and providing it with a de iure basis in

the legal and educational structures of a country. Serbo-Croatian could never have

been established as a national language without both legislation and agreement

(2.2.4). And Slovak in Czechoslovakia was recognized as a separate language only

after the Second World War, and officially established as such in one of the few

solid results of the Prague Spring of 1968 (D

ˇ

urovic

ˇ

, 1980).

It is also true that centralized control allows language to become an instrument

of political power. The rhetoric of Communism, for instance as it is illustrated

in Soviet journalistic style, was powerfully reinforced by the ability of a central

body to legislate on the language. The definition of the language itself was subject

548 11. Sociolinguistics