Sioshansi F.P. Smart Grid: Integrating Renewable, Distributed & Efficient Energy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

$30,000 to $39,999 13.6 12.2% 11,431 $1,143 3.3%

$40,000 to $49,999 11.0 9.9% 11,658 $1,166 2.6%

$50,000 to $74,999 19.8 17.8% 12,440 $1,244 2.0%

$75,000 to $99,999 10.6 9.5% 13,559 $1,356 1.5%

$100,000 or More 14.2 12.8% 15,382 $1,538 1.5%

Total 111.1 100%

Source: 2005 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, Energy Information

Agency

This chapter begins by describing and characterizing smart

grid, an elusive term that perhaps defies precise definition.

Some have approached this definitional challenge not by

describing the technologies that smart grid encompasses, but

by describing the desired attributes, as Hauser and Crandall

do in Chapter 1 of this volume. If smart grid means a

generation, transmission, and distribution system that is more

intelligent than today's because it takes advantage of the

leapfrog improvements in informational and computational

technologies, it is a useful term. If the term is used to set up a

false choice between “smart” and “dumb,” rather than to be

informative, it is pejorative and brings discussion to a halt.

Next, important questions related to smart grid underscore

that smart grid technologies and policies raise serious and

legitimate concerns. Some have argued that dynamic pricing,

which smart meters could enable, is more equitable than

current flat rates because low-income customers would have

lower electricity bills (e.g., as argued by Faruqui in Chapter

3). Others question whether residential ratepayers would

benefit from advance metering infrastructure [4], [5] and [6].

To what extent, if at all, equity analysis of dynamic pricing

bears on smart grid more generally is open for discussion.

There is nothing close to a majority view, let alone a near

consensus, that these technologies should be adopted. As one

251

report concluded: “The mindset of state regulators regarding

what constitutes prudent and value-adding smart grid

investments is currently in flux”[7]. Even EPRI [1, p. 4–1]

acknowledges that estimates of the benefits of smart grid are

questionable:

There have been a number of studies

which have estimated some of the benefits

of a Smartz Grid. Each varies somewhat

in their approach and the attributes of the

Smart Grid they include. None provides a

comprehensive and rigorous analysis of

the possible benefits of a fully functional

Smart Grid. EPRI intends to conduct such

a study, but it is outside the scope of the

effort presented in this report.

Note that EPRI's report, which does not contain a

“comprehensive and rigorous analysis” of smart grid, is a

report on the costs and benefits of smart grid. The claim that

smart grid would provide a net positive value to society is far

from certain, and society needs to honestly assess these costs

and benefits and not be “wowed” by the prospects of smart

grid [6]. Even if correct, this claim does not mean smart grid

would be equitable under any definitions of equity.

The chapter then turns to discussing different conceptions of

equity in the context of smart grid investments and policies.

There are multiple definitions of equity, and no one definition

is acceptable to all. A complete analysis of smart-grid-related

equity concerns, therefore, requires analyzing different equity

definitions and considerations. Understanding the conditions

under which multiple definitions may lead to the same

252

conclusion is extremely useful because it provides an opening

to move forward [2]. The chapter concludes with a discussion

of what types of questions and analyses regulators should ask

and require in order to evaluate the many issues that smart

grid raises, particularly those with equity implications.

Smart Grid Is Not Consistently Defined, Which

Leads to a Mismatch of Its Costs and Benefits

The most revealing quip about smart grid is this: “Smart grid

is the best thing ever, although we do not know what it is.”

Others have noted, perhaps wryly, that smart grid is

“variously defined”[8]. It seems as if every report has its own

definition. Beginning with the more specific and moving to

the more general, here are a few:

1. “The smart grid is a digital network that unites electrical

providers, power-delivery systems and customers, and

allows two-way communication between the utility and its

customers”[9].

2. “A smart grid is the electricity delivery system (from

point of generation to point of consumption) integrated

with communications and information technology for

enhanced grid operations, customer services, and

environmental benefits” (U.S. Department of Energy,

undated).

3. “Smart grids are electricity networks that can

intelligently integrate the behavior and actions of all users

connected to it—generators, consumers, and those that do

both—in order to efficiently deliver sustainable, economic

and secure electricity supplies”[10].

253

4. “Smart grid is an enhanced electric transmission or

distribution network that extensively utilizes internet-like

communications network technology, distributed

computing and associated sensors and software (including

equipment installed on the premises of an electric

customer) to provide

i. smart metering;

ii. demand response;

iii. distributed generation management;

iv. electrical storage management;

v. thermal storage management;

vi. transmission management;

vii. power outage and restoration detection;

viii. power quality management;

ix. preventive maintenance improves the reliability,

security and efficiency of the distribution grid;

x. distribution automation; or

xi. other facilities, equipment, or systems that operate in

conjunction with such communications network, or that

directly interface with the electric utility transmission or

distribution network, to provide the capabilities

described in clauses (i) through (x) in paragraph

(A)”[11].

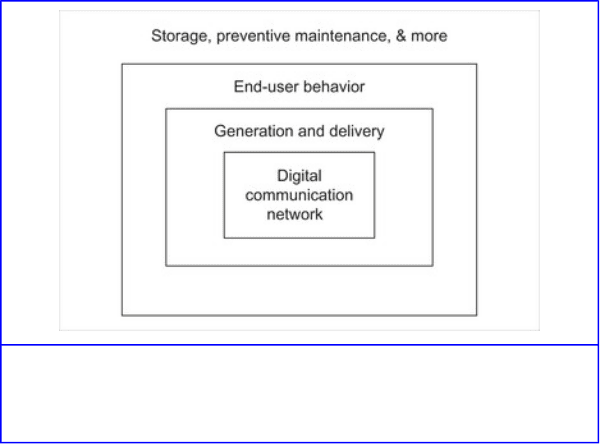

The first definition above includes only the digital

communication network; the second adds in the electric

delivery network including generation; the third adds user

behaviors; and the fourth includes everything but the

254

proverbial kitchen sink. Figure 4.1 illustrates these

ever-expanding definitions.

Figure 4.1

Diagram of ever-broadening definitions of smart grid.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to resolve the smart grid

definitional problem, and there are many more variations of

its definition not provided. The point here is that if one is not

extremely careful about what smart grid does and does not

include, it is impossible to assess its benefits, costs, and

equity implications. The real danger is that broader

definitions are used when discussing benefits, and narrower

ones are used when discussing costs. For instance, much is

made of smart grid's environmental and sustainability benefits

(see Chapter 5, Chapter 9, Chapter 10 and Chapter 18 in this

text), but much of the costs of achieving those benefits are not

included in smart grid cost-benefit analyses [1]. But at best,

smart grid enables, and in reality may only facilitate, the use

of renewable energy resources. Assuming that smart grid is an

255

enabler, the costs of renewable resources, electric vehicles,

and thermal and electric storage, which are very expensive,

must be considered in the cost-benefit analysis of smart grid.

If advocates of smart grid are going to claim the benefits of

smart grid from these additional technologies, they must

explicitly include their additional costs, which as noted, as

noted above, is not always done.

At worst, smart grid may not be necessary to increase the

penetration of cleaner energy technologies. For instance,

large-scale wind farms and large numbers of solar facilities

exist today without smart grid. A major expansion of nuclear

power or carbon capture and sequestration facilities does not

require smart grid at all. If this is the case, an analysis is

needed to determine the extent to which smart grid facilitates

cleaner energy technologies. This could be accomplished by

comparing the deployment of renewable resources, electric

vehicles, and grid storage with and without compulsory smart

grid so that the incremental benefits and costs of smart grid

technologies can be isolated.

This “but for” analysis must also incorporate the fact that

smart grid technologies will be naturally adopted by utilities

over time as existing equipment wears out and the costs of

smart grid technologies decline. For instance, the compulsory

purchase of smart meters by customers should be compared to

what would happen if smart meters were not made

compulsory. At some point in the future, smart meters would

be installed as replacement meters for existing meters that fail

or as new meters for new customers, and if and when the cost

savings to utilities of smart meters outweigh their installed

cost. In presenting the cost-benefit analysis of smart grid,

multiple deployment options must be considered, from

256

naturally occurring smart grid to accelerated deployment in

order to obtain a critical mass. EPRI raises the latter issue but

does not provide a comparison of costs and benefits under

multiple deployment scenarios [1, pp. 2–6]. In fact, it

acknowledges that the role of critical mass, tipping point, and

penetration of implementation in affecting smart grid costs

and benefits is unclear [1, pp. 2–6]. Assuming, which has yet

to be demonstrated, that a rapid and compulsory deployment

is preferable from a cost-benefit perspective to a naturally

occurring one, it is not clear that the additional savings of the

former should outweigh the non-compulsory advantages of

the latter. In fact, several authors have noted the importance

of obtaining customer buy-in, particularly with smart meters,

if smart grid is to be successful [6] and [30]. Rushing

deployment may undercut public support.

Furthermore, policy changes may also be required to achieve

many of the benefits of smart grid investments. For instance,

if regulators do not permit or restrict dynamic pricing or

customers do not respond as anticipated to dynamic pricing,

then many of the benefits of smart meters will not materialize

[12]. Some regulators are reluctant to approve dynamic

pricing because of equity concerns based upon positions taken

by consumer advocates [4] and [6]. If transmission expansion

to support large-scale wind does not occur, either due to

problems with siting or determination of how costs are to

allocated “both perennial problems in the United States” then

many of the renewable energy benefits that smart grid is

supposed to enable may not occur.

There are other fundamental questions related to smart grid

that must be addressed. The U.S. Department of Energy, for

example, has issued three requests for information listing

257

dozens of fundamental questions about smart grid for

stakeholders to address [13]. These questions cover

substantive and major issues such as whether it is preferable

to wait before adopting major smart grid investments to learn

more about the technologies and costs, how to calculate costs

and benefits, how to determine who pays what, what should

be done if there are cost overruns or benefits do not

materialize, how data privacy and cyber security will be

ensured (see [14]), and the list goes on. The point here is not

to answer these questions, but to suggest that regulators

should not consider the compulsory adoption of smart grid

paid for by ratepayers until these questions have been

coherently addressed.

Take the case of smart meters, a maturing technology, but

perhaps one of the most misunderstood in the suite of smart

grid technologies. With both costs and need uncertain, and

with the prospect of further cost reductions and technological

improvements, a compulsory approach to the adoption of

smart meters becomes questionable. Only about 6% of

electric meters are smart, so our experience is still limited. As

with most relatively new technologies, further cost reductions

are expected [7]. Before mandating the compulsory purchase

of smart meters by ratepayers, regulators should require

utilities to evaluate when, if at all, in the future would the

utility would be willing to pay for meter replacement because

smart meters save more money for the utility than they cost.

Recall that many of the benefits of smart meters—for

example, reduced maintenance, billing, and customer service

costs—benefit the utility. Compulsion has an equity cost.

Granted, while hard to quanify it is nonetheless a cost; but it

is assumed to be zero when analyzing smart meter and other

smart grid deployments. With approximately 60 million smart

258

meters planning to be installed in the United States [15],

regulators need to start addressing these questions before it is

too late.

But there is even a more fundamental question: some analysts

question whether the smart meter should be the gateway to

the home for smart grid technologies [7] and [13]. Perhaps the

meter can be directly bypassed and communication with the

grid can be done directly with smart appliances. Perhaps a

component can be added to existing meters to make them

functionally smart. If so, why (subject to obvious safety

issues) should that component be owned by the utility? Also,

why must a customer use a utility-owned communication

network versus the internet?

The above analysis also applies more generally to smart grid

investments. Assume that the above definitional and

uncertainty issues can be worked through—along with data

privacy and security issues, no small challenges—but

advocates of smart grid are misapplying cost-benefit analysis.

The decision rule employed by advocates of compulsory

smart grid investments is that so long as the benefit-cost ratio

is greater than 1, or the net present value is greater than zero,

then compulsory investments should proceed. This is

incorrect because it implicitly assumes that the status quo is

static and smart grid would not occur on its own in the future.

It may be the case that the natural penetration of smart grid

technologies, albeit at a slow pace, has a smaller benefit-cost

ratio than a compulsory and accelerated approach. Unless this

comparison is made, regulators will not be completely

informed. But even if the compulsory approach yields a

greater benefit-cost ratio than the naturally occurring

approach by saving on rollout costs, regulators may

259

reasonably conclude that the additional expected benefits of

the compulsory approach do not outweigh the equity costs of

compulsion, which are not incorporated into a benefit-cost

analysis. Or regulators may want to consider policies that

protect consumers, particularly low-income families, when

authorizing smart grid investments. Where exactly to draw

that line is not clear, but that should not mean that utilities

and regulators ignore the issue.

But there is still another major issue: even if a cost-benefit

analysis is performed and used correctly, it may still be

factually wrong, that is, in reality the investment may not turn

out as expected. At this point, some history is in order. The

U.S. electric utility industry does not have a perfect track

record with respect to cost effectiveness and completion of

long-term investments. Two examples come immediately to

mind: nuclear power and long-term power contracts under the

Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA). In

both cases, ratepayers ended up being stuck paying for much,

if not most, of the cost overruns and out-of-market or

stranded costs. Estimates of stranded costs vary, but most

range from $100 to $200 billion, in late 1990s dollars [16].

Of course, just because past investments did not always work

out does not automatically mean smart grid investments will

not do so. But the replacement of existing, working meters

with smart meters raises questions about stranded costs. In

fact, one utility concedes that its plan to install meters will

result in $42 million of stranded costs if 600,000 smart meters

are deployed [17]. It is also interesting to compare the cost

estimates of smart grid over time. In 2004, EPRI estimated

the cost of smart grid at $165 billion (pp. 1–2); seven years

later, the cost is between $338 to $476 billion [1, p. 1–4].

260