Sioshansi F.P. Smart Grid: Integrating Renewable, Distributed & Efficient Energy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

offerings. Conventional financial models may be employed,

but electricity prices do not conform to some of the

assumptions these models require, which means that they may

not produce consistent and therefore reliable results. The level

of hedging premiums therefore remains the subject of

speculation.

Comparing the posted prices of competitive retailer products

with the cost of paying spot prices for that load is one avenue

for establishing risk premiums, albeit a somewhat flawed one.

Such a comparison uses already known spot market prices

and retail prices that were based on the retailer's price

expectations. However, it is at least a rudimentary indicator of

implied risk premiums. Applying that reasoning to

competitive markets in the Northeast yields implied

premiums of 15–40% for a fully hedged service. The

difference among retailers’ rates for equivalent service

reflects their forward market view (each's expectations of

prices), along with other transactional considerations, like the

cost of operating a retail business (acquiring and servicing

customers).

Auctions and RFPs for default service provide another hedge

cost indicator. The results of the auction for default service in

Illinois caused some to conclude that the implied risk

premium was 20–40%. Recent studies of price response by

ISO-NE utilized risk premiums that are graduated in the

degree of risk of the pricing plan; RTP has the lowest (3–5%),

TOU even higher (8%), and the uniform rate had the highest

(15%). Under these risk premiums, the analysis concluded

that the majority of benefits of price response redound to

those that adopt that behavior.

241

Estimating the Hedging Cost Premium in Flat

Electricity Rates

How can the hedging cost premium be quantified? In one

approach, the hedging premium is considered to be

exponentially proportional to the volatility of loads, the

volatility of spot prices, and the correlation between loads and

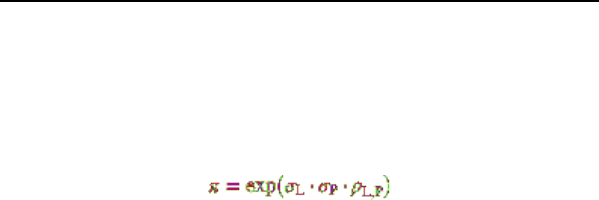

spot prices. This can be represented as follows:

where:

π = Risk Premium

σ

L

= Load Volatility

σ

P

= Spot Price Volatility

ρ

L,P

= Correlation Between Load and Spot Price

For example, if price volatility was assumed to be 0.6, load

volatility was 0.2, and the correlation between load and the

spot price was 0.4, the resulting estimate of the hedging

premium would be 5%. In other words, on average, customers

are paying 5% more than they would if they were simply

exposed to spot prices.

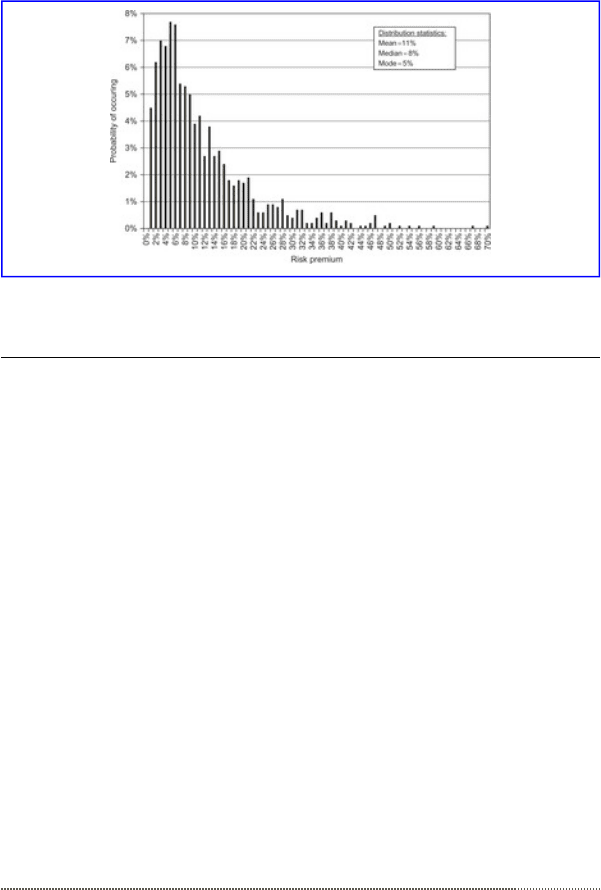

With an assumption about the distribution of these three

variables, a Monte Carlo simulation can be used to

approximate a distribution around this premium. Assuming

that the variables are all triangularly distributed with a

minimum of 0 and a maximum of 1, a Monte Carlo

simulation of 1,000 iterations produces the hedging premium

distribution shown in the following figure.

242

Simulated Distribution of Hedging Cost Premium

The mean, median, and mode of the premium are 11%, 8%,

and 5%, respectively. The standard deviation is 10%.

References

[2] http://documents.dps.state.ny.us/public/Common/

ViewDoc.aspx?DocRefId={4FA9C260-CE37-4FA983CA1D7904409

[3] Of course, benefits over multiple years would be much

higher. In a full cost-benefit analysis, all relevant costs

would also need to be factored in.

[4] Faruqui, A.; Hledik, R.; Tsoukalis, J., The power of

dynamic pricing, The Electricity Journal (April 2009).

[5] Its applicability to residential customers is prevented by

state legislation that has frozen portions of residential

rates in order to recover the costs of the energy crisis of

2000–2001 from the unfrozen portions.

[6] FERC Staff, A National Assessment of Demand Response

Potential, Washington, DC, June 2009.

243

[7] Faruqui, A.; Hledik, R.; Newell, S.; Pfeifenberger, J., The

power of five percent, Electr. J. Vol. 20 (October 2007).

[8] Revenue neutrality means that the revenue collected from

the class to which the new rate is being applied would

not change from the revenue collected under the old

rates. In the case of dynamic pricing, this means that the

customer who has a load factor equal to the class average

would see no change in her or his bill. Load factor is the

ratio of a customer's average demand to her or his peak

demand.

[9] Several of the test results are discussed in A. Faruqui, R.

Hledik, S. Sergici, “Rethinking pricing: The changing

architecture of demand response,” Public Utilities

Fortnightly, January 2010.

[10] http://news.smh.com.au/breaking-news-national/

vic-govt-to-review-smart-meters-20100203-nd88.html.

[11] Vickrey, W., Responsive pricing of public utility

services, Bell J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2 (1971) 337–346.

[12] Schweppe, F.C.; Caramanis, M.C.; Tabors, R.D.; Bohn,

R.E., Spot Pricing of Electricity. (1987) Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

[13] Hirst, E., Price-responsive demand in wholesale markets:

Why is so little happening?Norwell, MA. Electr. J. (May

2001); ISBN: 0-89838-260-2.

[14] Bolton, D.J., Costs and Tariffs in Electricity Supply.

(1938) Chapman & Hall, London.

[15] B. Alexander, “Dynamic pricing? not so fast! a

residential consumer perspective,” Electr. J., Vol. 23,

39–49. July 2010 and S. Brand, “Dynamic pricing for

residential electric customers: A ratepayer Advocate's

Perspective.” Electr. J., Vol. 23, 50–55. July 2010.

244

[16] http://www.mtc.ca.gov/news/info/toll_increase.htm.

[17] Cross, Robert G., Revenue Management. (1998)

Broadway Books, New York, NY.

[18] J. Upton, “Giants make a dynamic move: Team to

implement pricing strategy for nonseason tickets.” The

Examiner, February 9, 2010.

[19] http://sabres.nhl.com/club/page.htm?id=39501.

[20] See the appendix at the end of this chapter for a

discussion of the hedging premium.

[21] F.A., Wolak, An Experimental Comparison of Critical

Peak and Hourly Pricing: The PowerCentsDC program,

In: Prepared for The 15th Annual Power Conference,

The Haas School of BusinessU.C. Berkeley, March 13.

(2010).

[22] Additional details are available in Ahmad Faruqui and

Ryan Hledik, “Transition to Dynamic Pricing.” The

Public Utilities Fortnightly, March 2009.

[23] Chao, H., Price-responsive demand management for a

smart grid world, Electr. J. Vol. 23 (February 2010).

245

246

Chapter 4. The Equity Implications of Smart

Grid

Questioning the Size and Distribution of Smart Grid

Costs and Benefits

Frank Felder

Chapter Outline

Introduction 85

Smart Grid Is Not Consistently Defined, Which Leads

to a Mismatch of Its Costs and Benefits 88

The Compulsory Nature of Smart Grid Raises

Fundamental Equity Concerns 93

Smart Grid Raises Other Equity Concerns Besides

Compulsion 95

Conclusions 98

References 99

Important equity questions remain unanswered with respect to smart grid and center on both the size

and distribution of its costs and benefits Smart grid is an ambiguous term with multiple meanings It

captures the general notion that the electric power system could be upgraded with new measurement,

data, and computational technologies to provide consumers, system operators, and transmission and

distribution utilities with additional functionalities that are purported to deliver significant benefits to

utilities, ratepayers, and society in the form of lower costs, improved reliability, and lower

environmental impacts Unfortunately, by using this term, some advocates of smart grids may be

making the assumption rather than the case that these technologies work, that their benefits to society

will exceed their costs, and that these technologies are equitable Regulators asked to approve smart

grid investments must explicitly consider multiple definitions of equity, require utilities to provide

more choices to consumers, and probe the cost-benefit analyses that are used to justify large smart grid

investments

247

Cost effectiveness of smart grid, cost allocation, equity

Introduction

The many and various combinations of technologies

encompassed by the term smart grid are large and uncertain

investments. A major recent report, but by no means the only

one, places the cost of smart grid for the United States alone

between $338 and $476 billion over a twenty-year period

with net benefits estimated in the range of $1,294 to $2,028

billion as shown in Table 4.1[1]. Stated differently, the cost

estimates vary by almost 41% and benefit estimates vary by

almost 57%. There is no guarantee that the potential net

societal benefits will occur, either for society as a whole or

for particular segments of society, particularly low-income

families. The above cited study, for example, excludes the

costs of generation and transmission expansion needed to

support additional renewable resources, which would provide

much of the environmental benefit associated with smart grid

and also excludes the customer costs for smart-grid-ready

appliances needed to capture fully the benefits of smart grid

for consumers [1]. Chapter 7 of this text provides rather rough

“guesstimates” of the benefits of smart grid, on a global scale

and suggest that EPRI may be under-estimating the benefits.

Table 4.1

Summary of Estimated Costs and Benefits of the Smart Grid

20-Year Total ($ billion)

Net Investment Required (Cost) 338–476

Net Benefit 1,294–2028

Benefit-to-Cost Ratio 2.8–6.0

Source: EPRI [1].

Besides questions of the relative size of costs and benefits, a

host of equity questions surround smart grid. For the most

248

part, because these smart grid investments would be

recovered through mandatory charges assessed in utility rates,

they thus raise substantial equity issues that must be

considered and analyzed. Whether future utility bills would

decrease or not increase as much without smart grid is much

less certain. Smart grid advocates are making an analogy with

smart phones, computers, and other electronic devices that

have taken off over the last twenty years but fail to

acknowledge the fundamental difference between smart grid

and consumer electronic devices. With smart grid, consumers

are being asked to guarantee much if not most of these

investments. There is little discussion of the issue and

importance of choice. Instead, arguments are made, for

example in the case of advanced meters, that one size must fit

all. The meter purchase and selection are not left up to the

consumer but to the utility and the regulators who must

approve the investments. The power of the technological

revolution in computers, communications, and electronic

devices is that it gives consumers a wide range of choices,

including the choice not to purchase a particular device or use

a service.

The compulsory nature of cost recovery is critical to any such

equity analysis. Even if an individual consumer would be

better off as a result of contributing to the recovery of smart

grid investments, the requirement to do so may be considered

inequitable. There are also other fundamental and critical

questions regarding the different equity concerns with smart

grid and the conditions under which smart grid would result

in equitable outcomes. That being said, the fact that equity

issues can be raised should not be a reason to halt debate.

Instead, equity considerations must be defined precisely,

articulated clearly, and analyzed thoroughly as applied to

249

smart grid. A lot more analysis and discussion are needed to

answer key questions, both related to the equity of smart grid

investments and to their costs and benefits, before regulators

should proceed.

In addition to the compulsory nature of cost recovery is the

fact that lower income consumers spend a greater percentage

of their income on energy, including electricity, than higher

income consumers: the lowest income category in the United

States spends about 15% of its income on electricity, whereas

the highest income bracket spends approximately 1.5%, ten

times less on a percentage basis [2]. Thus, raising the cost of

electricity is regressive: it harms lower income consumers

more than higher income ones (see Table 4.2). Given how

vital electricity is to the health and safety of families, it is not

considered to be a commodity but a merit good [3] and [4].

This means, if one accepts this definition, that its availability

and pricing should be based upon need for some, not ability to

pay. These three factors—compulsory recovery of costs,

energy costs disproportionately affecting the poor, and the

fact that electricity is a merit good—combine to raise

important equity issues with respect to smart grid.

Table 4.2

U.S. 2005 Electricity Consumption and Costs by Household Income

U.S. Households Annual Electricity

Household Income Number (million) % kWh Cost % of Income

Less than $10,000 9.9 8.9% 7,854 $785 15.7%

$10,000 to $14,999 8.5 7.7% 8,710 $871 7.0%

$15,000 to $19,999 8.4 7.6% 9,506 $951 5.4%

$20,000 to $29,999 15.1 13.6% 10,040 $1,004 4.0%

Source: 2005 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, Energy Information

Agency

250