Schulz M. Control Theory in Physics and Other Fields of Science: Concepts, Tools, and Applications

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

2.4 General Optimum Control Problem 45

As in the calculus of variations, we can encounter most diverse situations

which occur during the solution of control problems with the aid of Pon-

tryagin’s maximum principle. Such problems are the lack of solutions, the

necessary smoothness of solutions, or the existence of a set of admissible tra-

jectories which satisfy the maximum principle and are not optimal. Because

a large class of optimal control problems concerns bounded sets of admissible

controls one often get the impression that such problems are always soluble.

But this is not correct. A typical counter example are sliding processes which

cannot solved straightforwardly by the application of Pontryagin’s maximum

principle; see below.

2.4.4 Applications of the Maximum Principle

In the following chapter we present some simple, but instructive examples

of the application of Pontryagin’s maximum principle. Of course, these ex-

amples have more or less an academic character, but they should show the

large variety of optimum control problems, which can be solved by using

the Hamilton approach together with the maximum principle. More applica-

tions and also realistic examples can be found in the comprehensive literature

[21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26].

Linear Control Problems

All terms of a linear control problem contain the control functions up to the

first-order. Such problems are very popular in several problems of natural

sciences. Important standard problems are additive and multiplicative con-

trolled processes. Let us illustrate the typical problems related to these types

of optimal control by some simple examples.

Sliding Regimes

We first study two simple processes with additive control. The first example

is a so-called 1d-sliding process,

T

0

dtX

2

→ inf

˙

X = u |u| = αX(0) = 0 X(T )=θ.

The corresponding Hamiltonian of this problem is H = Pu − X

2

and

we obtain the preoptimal control u

(∗)

= α for P>0andu

(∗)

= −α for

P<0. The preoptimized Hamiltonian is simply H

(∗)

= α |P |−X

2

.Thus,

we obtain the canonical equations

˙

P

∗

=2X

∗

and

˙

X

∗

= α for P

∗

> 0and

˙

X

∗

= −α for P

∗

< 0. Furthermore, we introduce the initial condition P

∗

(0) =

P

0

. This relation may be justified by the transversality conditions (2.73).

Considering all initial conditions, we find X

∗

(t)=αt and P

∗

(t)=P

0

+ αt

2

if

P

0

> 0andX

∗

(t)=−αt and P

∗

(t)=P

0

− αt

2

for P

0

< 0, i.e., an initially

positive (negative) momentum remains positive (negative) over the whole time

46 2 Deterministic Control Theory

interval. The behavior for P

0

= 0 is undefined within the framework of the

maximum principle. The final condition requires αT = |θ|, i.e., we find a

unique and optimal solution only for α = |θ|/T . In this case, we have the

optimal control u

∗

(t)=|θ|/T sign θ and the optimal trajectory X

∗

(t)=θt/T.

No admissible control exists for αT = |θ|.

On the other hand, it is easy to see that a positive value of the functional

results from any admissible trajectory. The set of admissible trajectories is

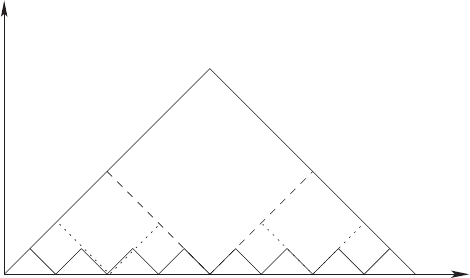

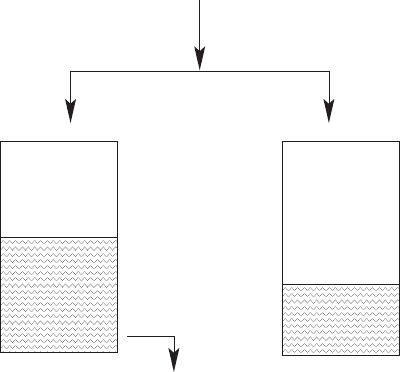

empty only for αT < |θ|. For example, Fig. 2.5 shows a set of admissible

trajectories X

k

(t)forθ = 0. The corresponding value of the functional tends

to zero on the sequence X

1

(t), X

2

(t), . . . . Furthermore, it is easy to show

that the trajectories X

k

(t) converge uniformly to X

∞

(t) = 0. In contrast, the

sequence of controls converges to anything.

t

T

X

X

X

X

4

3

2

X

1

Fig. 2.5. The first four trajectories X

1

,...,X

4

of a set of admissible trajectories for

θ = 0 converging to the limit trajectory X(t) = 0 for all t ∈ [0,T]

As a second example we consider a particle of mass m = 1 moving on a

straight line under the effect of a unique force u and a Newtonian friction −µ ˙x

from the position x(0) = 0 to x(T )=x

e

. The initial and final velocities should

vanish, ˙x(0) = ˙x(T ) = 0. Then we have a two-dimensional state X =(x, p),

where p =˙x is the momentum. The equations of motion are given by ˙x = p

and ˙p = −µp + u. The total amount of work injected into to system is simply

given by

R =

T

0

dtpu . (2.106)

A possible control problem is now to minimize the total work, R → inf, where

u is restricted to the interval −u

0

≤ u ≤ u

0

. To this aim we introduce the

generalized momentum P =(q, r) and construct the Hamiltonian

2.4 General Optimum Control Problem 47

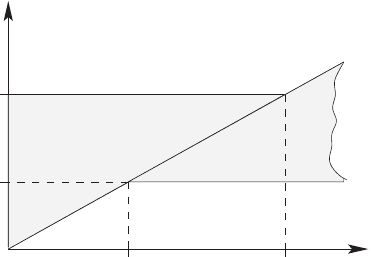

p

T

t

sliding

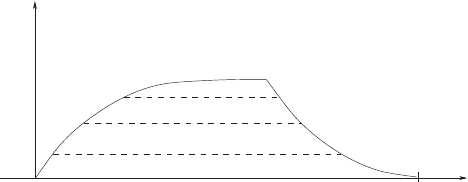

Fig. 2.6. Optimum momentum as function of time for different distances x

e

≤ x

crit

.

An initial acceleration regime followed by the braking regime exists for x

e

= x

crit

.

Shorter distances show an intermediate sliding regime with a constant velocity. The

sliding velocity decreases with decreasing x

e

H = qp + r(u − µp) − up . (2.107)

The preoptimal control function is u

(∗)

= u

0

sign (r −p), and the preoptimized

Hamiltonian is now H

(∗)

= qp + u

0

|r − p|−µpr. Thus we get the canonical

equations ˙x = p,˙q =0, ˙r = −q+µr+u

0

sign (r−p), and ˙p = −µp+u

0

sign (r−

p). There exists a unique solution only for x

e

= x

crit

with

(2 ln(1 + e

µT

) − 2ln2− µT )u

0

= µ

2

x

crit

, (2.108)

which corresponds to an acceleration regime with u

∗

= u

0

for 0 ≤ t<

µ

−1

ln

(1 + e

µT

)/2

and a subsequent braking regime with u

∗

= −u

0

for

µ

−1

ln

(1 + e

µT

)/2

<t≤ T . The largest velocity, p

max

= µ

−1

u

0

tanh µT/2,

is reached for the crossover between both regimes. No solution exists for

x

crit

<x

e

, while a sliding regime occurs for x

crit

>x

e

. Here, we also have

an initial acceleration up to the velocity p

0

<p

max

with u

∗

= u

0

, followed by

the sliding regime, defined by a constant velocity p(t)=p

0

= µ

−1

u

∗

and a

final braking from p

0

to p(T ) = 0 with u

∗

= −u

0

.

The crossover between the three regimes and the value of p

0

are determined

by unique solutions of algebraic equations which concern the total time T as

the sum of the duration of the three regimes and the total length x

e

of the

path from the initial point to the end point as sum of the three subpaths.

We remark that the velocity is a continuous function also for both crossover

points.

Multiplicative Coupled Control

Typical multiplicative controlled processes are chemical reactions of the type

A + C → 2C and C + B → 0 where the concentrations of A and C are

external changeable quantities which may be used to control the chemical

creation or annihilation of molecules of type B. The kinetics of the mentioned

reactions can be described by the balance equation for the concentration X

of the component C,

˙

X(t)=u(t)X(t), where the control function u(t)=

48 2 Deterministic Control Theory

k

1

c

A

(t) − k

2

c

B

(t) depends on the external changeable concentrations c

A

(t)

and c

B

(t) of the components A and B. The kinetic coefficients k

1

and k

2

of

both reactions are assumed to be constant. The control function is constrained

by the maximum concentrations of the A and B components. For the sake of

simplicity we assume −1 ≤ u ≤ 1. A possible control aim is the minimization

of the final concentration X(T ). Hence, we have to solve the problem

R =

T

0

dt

˙

X(t)=X(T ) − X

0

=

T

0

dtu(t)X(t) → inf . (2.109)

The problem has the Hamiltonian H =(P (t) − 1)u(t)X(t) and the pre-

optimized control is simply u

∗

(t) = sign ((P (t) − 1) X(t)). Thus, we get

H = |(P (t) − 1) X(t)| and therefore

˙

X(t)=X(t)u

∗

(t)and

˙

P (t)=(1− P (t))u

∗

(t) . (2.110)

The free boundary condition for t = T requires P (T ) = 0 due to the transver-

sality condition (2.73). The evolution equations (2.110) prevent that neither

X nor 1 − P can be 0. Thus, the trajectory is defined by the solution of the

equation

dX

dP

=

X

1 − P

. (2.111)

We get the solution (1 − P ) X =const. and therefore u

∗

(t)=u

0

=const.

From here, it immediately follows from (2.110) that X(t)=X

0

exp(u

0

t)

and P (t)=1− exp(u

0

(T − t)). Finally, we obtain the optimum control law

u

∗

(t)=−sign X

0

.

Although realistic applications of the maximum principle on additive or

multiplicative controlled problems are much complicated as the simple exam-

ples suggest, the typical feature is a linear dependence of the Hamiltonian on

the control function. Thus, an unlimited range of the control, −∞ <u<∞,

leads usually to an undefined preoptimized Hamiltonian and therefore to a

lack of solutions.

Time Optimal Control

A large class of problems are minimum time problems. Basically, an optimum

time problem consists in steering the system in the shortest time from a suit-

able initial point of the phase space to an allowed final state. The functional

to be minimized is in this case simply

R = T =

T

0

dt (2.112)

and the Hamiltonian (2.94) reduces to

H (t, X, P, u)=PF (X, u, t) − 1 . (2.113)

2.4 General Optimum Control Problem 49

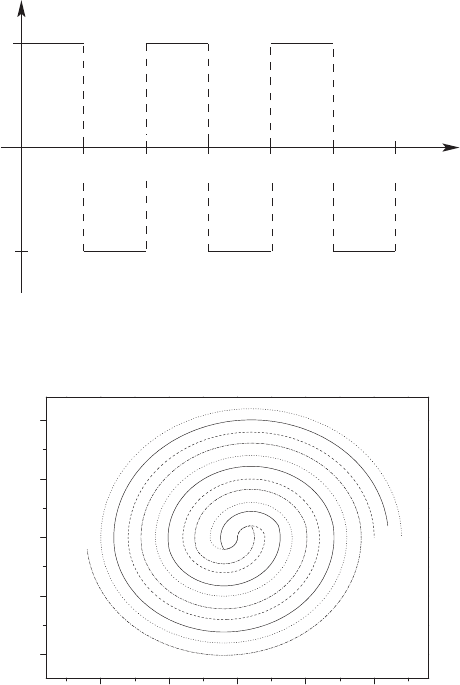

π2π3π4π5π6πωt

u

+1

−1

Fig. 2.7. Optimal control function for u

0

=1

-10 -5 0 5 10

-10

-5

0

5

10

1

3

2

4

v

x

Fig. 2.8. Several trajectories of the optimum oscillator problem in the position–

velocity diagram with the initial condition x

0

= v

0

= 0. The phase ϕ

0

of the control

function is π (for curve 1), π/2(2),0(3)and−π/2(4)

As an example we consider a harmonic oscillator, ˙x = p,˙p = −ω

2

x + u, with

the state vector X =(x, p). The external force u is restricted by −u

0

<u<u

0

and may be used for the control of the system. The corresponding Hamiltonian

reads H = qp+r(u−ω

2

x)−1 and the preoptimized control is u

(∗)

= u

0

sign r.

The canonical equations of the control problem are simply given by the above-

introduced mechanical equations of motion, ˙x = p,˙p = −ω

2

x + u

0

sign r,

and the adjoint set of differential equations, ˙q = ω

2

r,˙r = −q. We obtain

¨r + ω

2

r = 0 with the unique solution r = r

0

cos(ωt + ϕ

0

). Thus, the optimal

50 2 Deterministic Control Theory

control function u

∗

is a periodic step function with the step length τ = π/ω

and amplitude ±u

0

(Fig. 2.7). Finally, the solution of ¨x + ω

2

x = u

∗

(t) yields

the optimum trajectory. In principle, the optimum solution x

∗

(t)hasfour

free parameters, namely the initial position, x

0

= x(0), the initial velocity,

v

0

= v(0), the phase ϕ

0

of the control function and finally the time T . This

allows us to determine the minimum time for a transition from any initial state

(x

0

,p

0

) to any final state (x

e

,p

e

). The trajectories starting from a given initial

point can be parametrized by the phase ϕ

0

of the control function. Obviously,

the set of all trajectories covers the whole phase space, see Fig. 2.8.

Complex Boundary Conditions

Problems with the initial state and final state, respectively, constrained to

belong to a set X

0

and X

e

, respectively, become important, if the preparation

or the output of processes or experiments allows some fluctuations. We refer

here to a class of problems with partially free final states. A very simple

example [27] is the control of a free Newtonian particle under a control force u,

−u

0

<u<u

0

. The initial state is given, while the final state should be in the

target region −ξ

e

≤ x

e

≤ ξ

e

and −η

e

≤ p

e

≤−η

e

. We ask for the shortest time

to bring the particle from its initial state to one of the allowed final states. The

equations of motion, ˙x = p,˙p = u, require the Hamiltonian, H = qp + ru −1.

Thus, the preoptimized control is u

(∗)

= u

0

sign r. The canonical equations

of the control problem are given by the equations of motion, ˙x = p,˙p = u

0

sign r, and the adjoint equations, ˙q =0, ˙r = −q. Thus, we obtain ¨r =0

with the general solution r = r

0

+ Rt and q = −R. The linearity of r(t)

with respect to the time suggests that u

(∗)

switches at most once during the

flight of the particle from the initial point to the target region. First, we

consider all trajectories which reach an allowed final state without switch.

These trajectories are given by x(t)=x

e

+ p

e

t ± u

0

t

2

/2andp(t)=p

e

± u

0

t,

and therefore, x∓p

2

/2u

0

= x

e

∓p

2

e

/2u

0

. Hence, the primary basin of attraction

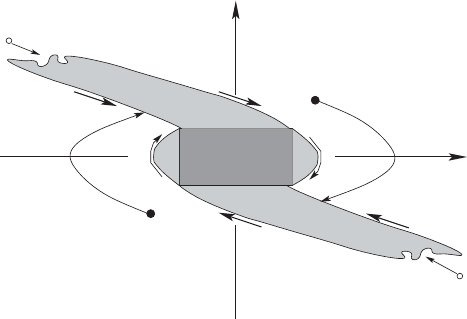

with respect to the target is the gray-marked region in Fig. 2.9. All particles

with initial conditions inside this region move under the correct control but

without any switch of the control directly to the target. All other particles

are initially in the secondary basin of attraction. They move along parabolic

trajectories through the phase space into the primary basin of attraction. If

the border of this basin was reached, the control switches as the particle moves

now along the border into the target region.

Complex Constraints

In the most cases discussed above, the constraints were evolution equations

of type (2.53). But there are several other possible constraints. One of these

possibilities is isoperimetric constraints where some functions of the state and

the control variables are subject to integral constraints; see Sect. 2.4.1. Other

2.4 General Optimum Control Problem 51

x

p

Fig. 2.9. The structure of the primary and secondary basins of attraction. The

particles move in the direction of the arrows

cases are constraints where some functions of the state and the control func-

tions must satisfy instantaneous constraints over the whole control interval

0 ≤ t ≤ T

g(t, X(t),u(t)) = 0 or G[t, X(t),u(t)] ≤ 0 . (2.114)

The first class of these constraints can be used to eliminate some state vari-

ables or control functions from the optimum control problem before the opti-

mization procedure is carried out.

The inequality constraints can be transformed into an equality constraint

by addition of a new control variable u(t)

G[t, X(t),u(t)] + u(t) = 0 with u(t) ≥ 0 . (2.115)

Then we may proceed as in the case of an equality constraint. Thus, the new

control variable enters the original optimum control problem and we can apply

Pontryagin’s maximum principle as discussed above. In the same way, we may

consider evolution inequalities

˙

X(t) ≤ F (X, u,t) . (2.116)

Relations of this type are very popular in nonequilibrium thermodynamics

[28, 29, 30]. Another important class of constraints, as in several branches of

natural sciences, are problems where the state variables must satisfy equality

(or inequality) constraints at M isolated subsequent time points, i.e., con-

straints of the form

g

i

(t

i

,X(t

i

),u(t

i

)) = 0 for 0 <t

1

<t

2

< ···<t

M

<T . (2.117)

Typical examples are rendezvous problems where particles collide at a certain

time, or where space shuttles and space stations meet at a certain time. We

remark that when these constraints are present, the control functions, the

52 2 Deterministic Control Theory

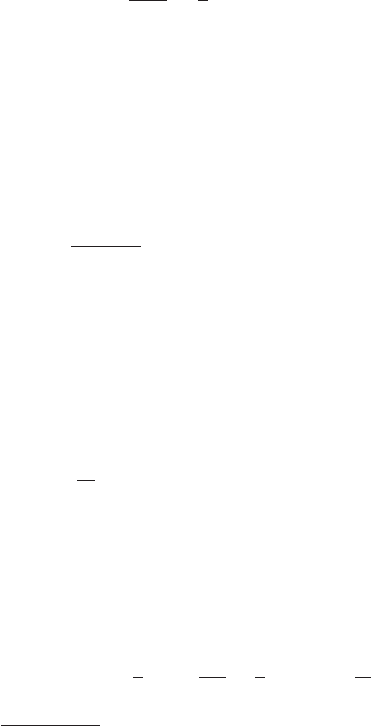

v

III

u

Fig. 2.10. Two tanks with common input

generalized momenta as well as the Hamiltonian may be discontinuous at the

isolated time points t

i

.

We finish this chapter with a simple example [27] related to a control

under global instantaneous equality constraints. To this aim we consider a

system of two tanks; see Fig. 2.10. The outgoing flow of tank I is proportional

to the volume of the liquid, while tank II is closed. The two tanks are fed

through a constant input flow, which can be divided in any way, u+v =const.

where u and v are the both subflows. Obviously, the evolution equations of

this system are given by ˙x = −x + u and ˙y = v, where x and y are the

heights of the liquid in tank I and tank II, respectively. The problem is to

drive the system in the shortest time from the initial state (x

0

,y

0

)tothe

final state (x

e

,y

e

). The Hamiltonian of this problem is H = q(u − x)+pv −

1. Considering the equality constraint, we obtain the reduced Hamiltonian

H = q(u −x)+p(1 −u) − 1 with the control u ∈ [0, 1] and the adjoint states

(q, p). Thus, we find the preoptimal control u

(∗)

= (sign (q − p)+1)/2and

therefore H = |q − p|/2+q(1/2 −x)+p/2 −1. The corresponding canonical

equations are ˙x = −x + (sign (q − p)+1)/2, ˙y =(1− sign (q − p)) /2, and

˙q = q,˙p = 0. Thus we obtain the solution p = p

0

and q = q

0

exp t. Hence,

q − p changes the sign at most one. Therefore, we have four scenarios:

1. u

(∗)

=0fort ∈ [0,T]: This regime requires y = y

0

+t and x = x

0

exp {−t}.

In other words, the final conditions require y

e

− y

0

=lnx

0

/x

e

and the

final time is simply T = y

e

− y

0

.

2. u

(∗)

=1fort ∈ [0,T]: Here, we get y = y

0

= y

e

and x =1+(x

0

−

1) exp {−t}. A unique solution exists only for 1 <x

e

<x

0

,or1>x

e

>

x

0

, and the minimum time is T =ln(x

0

− 1)/(x

e

− 1). Obviously, this

2.4 General Optimum Control Problem 53

scenario is included in the first and the both subsequent cases as the

special realization for y

0

= y

e

.

3. u

(∗)

=1for0<t<τ and u

(∗)

=0forτ<t<T: In this case, we get the

final conditions x

e

=exp{−T + τ }+(x

0

−1) exp {−T } and y

e

= y

0

+T −τ.

Thus, τ =ln(x

0

− 1) − ln (x

e

exp {y

e

− y

0

}−1) and T = τ + y

e

− y

0

.A

positive τ exists for (i) y

e

−y

0

< ln x

0

/x

e

, x

e

exp {y

e

− y

0

} > 1andx

0

> 1

and for (ii) y

e

− y

0

> ln x

0

/x

e

, x

e

exp {y

e

− y

0

} < 1andx

0

< 1, but the

final time T of case (ii) is larger than T of the subsequent control regime.

Thus, there remains only case (i).

4. u

(∗)

=0for0<t<τ and u

(∗)

=1forτ<t<T: In this case we obtain

the final conditions y

e

= y

0

+ τ and x

e

=1+(x

0

− exp τ )exp{−T }.

That means we have τ = y

e

− y

0

and T =ln(x

0

− exp τ ) − ln (x

e

− 1).

The relation τ<Trequires (i) y

e

− y

0

> ln x

0

/x

e

, x

e

< 1andx

0

<

exp {y

e

− y

0

} or (ii) y

e

− y

0

< ln x

0

/x

e

, x

e

> 1andx

0

> exp {y

e

− y

0

},

but the elapsed time T of case (ii) is larger than T of the previous control

regime.

Figure 2.11 shows an illustration of the obtained regimes.

e

1

−∆

e

∆

1

x

x

e

0

(3)

(4)

(1)

Fig. 2.11. The regions of existing optimal solutions with ∆ = y

e

− y

0

. The first

regime corresponds to the straight line separating regime 3 from regime 4

2.4.5 Controlled Molecular Dynamic Simulations

A large class of numerical studies of molecular systems are so-called molecular

dynamic simulations. In principle, these techniques numerically solve the set

of Newtonian equations of motion corresponding to the system in mind. Such

a solution leads to a microcanonical description of the system which is char-

acterized by the conservation of the total energy of the system. In general,

54 2 Deterministic Control Theory

molecular dynamic methods are always related to an appropriate set of de-

terministic evolution equations. The introduction of the temperature requires

the consideration of a thermodynamic bath which can be interpreted as the

source of stochastic forces driving the system. The corresponding evolution

equations now become a stochastic character and they are no longer an object

of molecular dynamics methods.

However, sometimes it is reasonable to simulate the bath by deterministic

equations. This can be done by two standard methods, namely a combination

of molecular dynamics equations with additional constraints, or the formal

extension of the original system. The first case [31, 32] considers additional

constraints, for example, the conservation of the kinetic energy

E

kin

=

M

i=1

m ˙x

2

i

2

=

3

2

MT (2.118)

with M the number of particles and T the desired temperature. The cor-

responding equations of motion follow from the above-discussed variational

principle

¨x

i

= F

i

− λ ˙x

i

with i =1,...,M (2.119)

with F

i

the current force

7

acting on particle i and the Lagrange multiplier

λ =

M

i=1

˙x

i

F

i

m

M

i=1

˙x

2

i

. (2.120)

In principle, this result may be classified as a control problem with one addi-

tional algebraic constraint.

The second type of generalized molecular dynamic simulations belongs to

an extension of the equations of motion [33, 34, 35]. These equations may be

interpreted as a typical result of the control theory. Here, we present a very

simple version. Let us assume that we have the canonical equations of motion

˙x

i

=

p

i

m

and ˙p

i

= F

i

− up

i

, (2.121)

where we have introduced an additional ‘friction’ term up

i

with the scalar

control function u. The implementation of u is a violation of the originally

conservative structure of the equations of motion. This contribution should

simulate the existence of the thermodynamical bath. Furthermore, we intro-

duce the performance

R =

T

0

dt

1

2

M

i=1

p

2

i

2m

−

3

2

MT

2

+

C

2

u

2

, (2.122)

7

This force is, of course, generated by the interaction of particle i with all other

particles.