Schmitt C.B. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Translation, terminology and style

87

Greek

lexical

and syntactic forms (particles, word order, certain participles,

various negative constructions) not present in classical Latin, medieval

translators developed codes which enabled them to map Greek originals on

to Latin versions with such precision

that

modern scholars can sometimes

reconstruct the Greek from the Latin.

27

What such versions can have meant

to contemporary readers who knew neither the translator's code nor the

Greek

that

it represented remains a puzzle, though the inclination of most

medieval

commentators to

treat

the Latia text as primary, not

intermediary, betrays the philological poverty of their philosophy. But it

was

tradition, not ignorance of Greek,

that

shaped the decisions

of

the best

medieval

translators. Jerome, who agreed with

Cicero

and Horace

that

sensus

was the criterion for secular translation, had as a student of the early

rabbis and a reader

of

the Septuagint insisted on rendering the

Bible

verbum

e

verbo since even its word order was an act

of

God.

Given

the celebrity

of

the

Vulgate

and its centrality for Christian philosophy, it was natural

that

Boethius

and

John

Scotus Eriugena should imitate Jerome in their

philosophical

translations and

that

later scholars should

follow

them.

28

While

the choice of meaning over word begins to distinguish Renaissance

philosophical

translation from

that

of this earlier age, it does not complete

the distinction nor do justice to the complexity of translation theory in the

fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Besides meaning and word, four other

choices

for the locus of correspondence in translation emerged in the early

modern period: language (lingua), structure (ratio), content (res) and style

(eloquentia, elegantia, venustas etc.).

Faced

directly or indirectly with questions about the need for new

versions

of texts already available in medieval translation, Renaissance

scholars routinely replied by echoing Chrysoloras' denunciation of the

verbal

method. Yet the response of the most famous of the Renaissance

theorists, Leonardo Bruni, was more modulated: 'First I preserve all the

meanings (sententias). . .; then,

if

it can be rendered word for word without

any awkwardness or absurdity, I do so gladly;

if

not,... I depart a bit from

the words to avoid absurdity.'

29

He and other Renaissance translators also

27.

Troilo

1931-2,

pp. 276-7; Pelzer 1964, pp. 159-60; Minio-Paluello

1972,

pp. 203-4,

2

5

f"

2

, 259-60;

Dictionary of Scientific Biography 1970-80, ix, p. 436 ('William of

Moerbeke');

Goldbrunner 1968,

p.

208.

28. Troilo

1931-2;

Bruni 1928, p. 96; Schwarz 1944; Kloepfer 1967, p.

19;

Stinger

1977,

pp.

19-20,101-

2,

107.

29.

Bruni

1741,1,

p. 17: 'Primo igitur sententias omnes ita conservo ut ne vel minimum quidem ab illis

discedam. Deinde si verbum verbo sine ulla inconcinnitate aut absurditate reddi potest, libentissime

omnium id ago; sin autem non potest, . . . paulisper a verbis recedo ut declinem absurditatem';

Medioevo e Rinascimento 1955, 1, p. 363 (Garin).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

88

Translation, terminology and style

explained why a consistent ad

verbum

method was unworkable. One great

obstacle was idiom: because a phrase like gero tibi

morem

('I humour you')

was

not the sum of its

lexical

parts

('I do' 4- 'to you' + 'conduct'), making

each word a unit of translation was literally senseless. Another was the

necessity for translating a

given

Greek word, such as Xoyos, by a variety of

Latin words (verbum, sententia, dispositio,

ratio)

in the same text, or the desire

to render a single Greek word, such as alo&rjrd, periphrastically in Latin (ea

quae sensibuspercipiuntur) .

30

Such technical considerations, reinforced by the

Ciceronian

conviction

that

the aesthetic and semantic properties of

language were inseparable and, perhaps, by the ambiguity of the word

sententia ('meaning'/'sentence'), convinced most

of

Bruni's successors to opt

for

meaning over word. But in the sixteenth century, some translators who

specialised

in philosophy, like Simone Simoni, praised the verbal method

for

its precision and for its terminological continuity with the medieval

textual tradition. Even in Bruni's century, George of Trebizond, whose

work

as a translator was broader

than

Simoni's, explicitly preferred to

render philosophical texts 'word for word as far as Latinity permits', a

decision

which seems to have governed Ficino's translating as

well.

31

Although

early modern scholars rejected the word as a unit

of

translation

in their ideological statements, in practice important translators like Ficino,

George

of Trebizond and Bruni continued to strive for some measure of

verbal correspondence when rendering philosophical texts. They had two

practical reasons for doing so. First, since the whole terminological

structure of western philosophy after

Cicero

rested on direct or indirect

Latinisation of Greek texts,

there

was a premium on preserving an

intellectual edifice erected at such cost. Lorenzo

Valla

was apparently

willing

to dispense with terminological continuity in order to advance his

own

powerful but idiosyncratic philosophy of language, as Perion and

others were ready to sacrifice it on the altar of Ciceronianism. But not all

Renaissance translators were so radical; their caution is evident in the fact

that

much

of

their work lies along a continuum between original translation

and simple revision.

32

Here was a second motive for modifying

rather

than

discarding the verbal method: revising, which for an acquired language is

30. Medioevo e Rinascimento 1955, 1, p. 344 (Garin); Bruni 1928, p. 84; Platon et Aristote 1976, p. 384

(Stegmann); Schmitt 1983a, p. 75.

31.

George of Trebizond 1984, p- i9

J

: 'conatus sum, ut in Physico etiam

feci

auditu, verbum verbo

prout Latinitas

patitur

reddere'; Minio-Paluello 1972, p. 265;

Harth

1968, p. 56; Schmitt 1983a, p.

81;

Hankins 1983, pp.

150—1.

32.

Garin

1951,

pp. 61,66-7,70,74,78;

Seigel

1968, pp.

116-19;

Schmitt 1983a, pp. 65-6; Hankins 1983,

pp. 154, 209-10.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Translation, terminology

and

style

8

9

quicker

and

safer

than

translating de

novo,

inclines one

to

consider

and

often

to preserve

a

predecessor's choice

of

words.

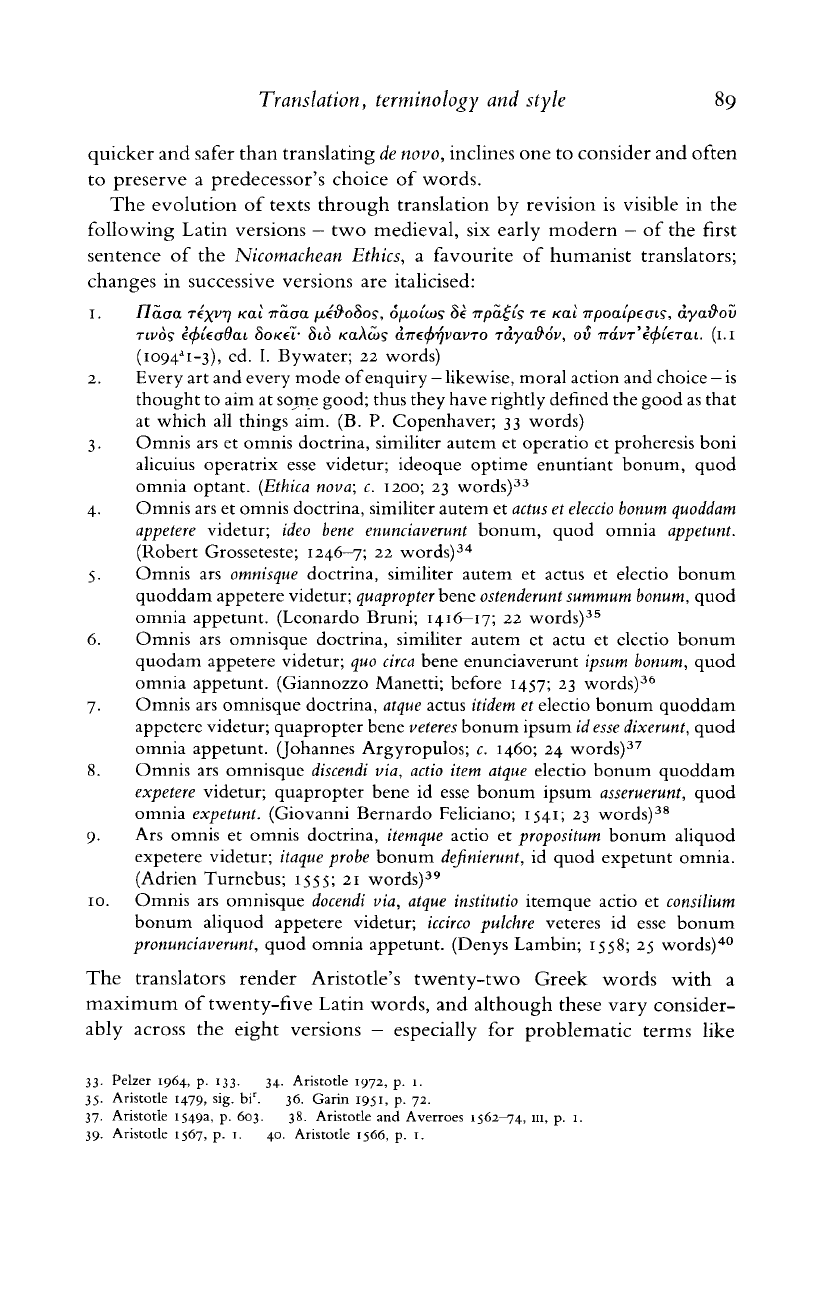

The

evolution

of

texts through translation

by

revision

is

visible

in the

following

Latin versions

—

two

medieval,

six

early modern

—

of

the

first

sentence

of the

Nicomachean Ethics,

a

favourite

of

humanist translators;

changes

in

successive versions

are

italicised:

1.

Паса

т€.ууг)

ка1

ттаоа

pe&oSos,

opoicos

be irpa^is те ка1

TTpoaipeais,

ayad'ov

TWOS

i<f)L€o6aL 8OK€L-

816

каХа>д

аттеф^уауто

rayad'ov, ov

TTOLVT'e^tVrcu.

(I.I

(i094

a

i-3),

ed.

I.

Bywater;

22

words)

2.

Every

art

and every mode

of

enquiry

-

likewise,

moral action and choice

-

is

thought

to

aim

at

some good;

thus

they have rightly defined the good as

that

at which

all

things aim. (B.

P.

Copenhaver;

33

words)

3.

Omnis

ars

et

omnis doctrina, similiter autem

et

operatio

et

proheresis boni

alicuius

operatrix esse videtur; ideoque optime enuntiant bonum, quod

omnia optant.

(Ethica nova;

c.

1200;

23

words)

33

4.

Omnis ars

et

omnis doctrina, similiter autem

et

actus

et

eleccio

bonum quoddam

appetere

videtur;

ideo bene enunciaverunt

bonum, quod omnia

appetunt.

(Robert Grosseteste;

1246-7;

22

words)

34

5.

Omnis

ars

omnisque

doctrina, similiter autem

et

actus

et

electio bonum

quoddam appetere videtur;

quapropter

bene

ostenderunt

summum

bonum,

quod

omnia appetunt. (Leonardo Bruni;

1416—17;

22

words)

35

6. Omnis

ars

omnisque doctrina, similiter autem

et

actu

et

electio bonum

quodam appetere videtur; quo

circa

bene enunciaverunt

ipsum bonum,

quod

omnia appetunt. (Giannozzo Manetti; before 1457;

23

words)

36

7.

Omnis

ars

omnisque doctrina,

atque

actus

itidem

et electio bonum quoddam

appetere videtur; quapropter bene

veteres

bonum ipsum

id esse dixerunt,

quod

omnia appetunt. (Johannes Argyropulos;

c.

1460;

24

words)

37

8. Omnis

ars

omnisque

discendi

via,

actio item atque

electio bonum quoddam

expetere

videtur; quapropter bene

id

esse bonum ipsum

asseruerunt,

quod

omnia

expetunt.

(Giovanni Bernardo Feliciano;

1541;

23

words)

38

9.

Ars

omnis

et

omnis doctrina,

itemque

actio

et

propositum

bonum aliquod

expetere videtur;

itaque probe

bonum

dejinierunt,

id

quod expetunt omnia.

(Adrien

Turnebus; 1555;

21

words)

39

10.

Omnis

ars

omnisque

docendi

via,

atque institutio

itemque actio

et

consilium

bonum aliquod appetere videtur;

iccirco

pulchre

veteres

id

esse bonum

pronunciaverunt,

quod omnia appetunt. (Denys Lambin; 1558;

25

words)

40

The

translators render Aristotle's twenty-two Greek words with

a

maximum

of

twenty-five Latin words,

and

although these vary consider-

ably

across

the

eight versions — especially

for

problematic terms like

33.

Pelzer 1964,

p.

133.

34.

Aristotle 1972,

p. 1.

35.

Aristotle 1479,

sig.

bi

r

. 36.

Garin 1951,

p. 72.

37.

Aristotle 1549a,

p.

603.

38.

Aristotle

and

Averroes 1562-74,

in, p. 1.

39. Aristotle 1567,

p. 1. 40.

Aristotle 1566,

p. 1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

90

Translation, terminology

and

style

fxe&oSos,

7Tpoaipeois,

Taya&ov

and

aTre^iqvavTO

—

the

continuity from

revision

to

revision

is

clear.

On

average, about three-quarters

of the

text

remains stable, reckoning stability

as the

tendency

to

preserve features

of

earlier versions

and

counting even stylistic

and

minor changes;

in

fact,

though this single case cannot necessarily

be

taken

as

representative,

it

suggests

greater distance between Grosseteste

and the

older medieval

version

than

between Grosseteste

and

Bruni

or

Lambin. Medieval

translations

ad

verbum

influenced even

the

humanist productions meant

to

replace them.

The

humanists' desire

to

make language (lingua)

an

additional locus

of

correspondence

for

translation

is a

stronger clue

to

their philological

intentions

than

criticism

of

the verbal method. Bruni formulated this point

most clearly

and

repeated

it

several times:'A translation is entirely correct if

it corresponds

to the

Greek;

if

not,

it is

corrupt. Thus,

all

argument about

translation moves from

one

language (lingua)

to

another.'

41

His conception

of

translation

as the

transference

of an

author's text from lingua Graeca

to

lingua Latina meant

that

both version

and

original, along with their

linguistic

contexts, were human objects, ephemeral

but

philologically

accessible,

conditioned

by

time

but

knowable through history.

The

very

different ideas

of

Bruni's most forceful critic,

Alonso

de

Cartegena,

highlight

the

diachronic character

of

Bruni's philological scheme

of

translation. Where Bruni insisted

on

fidelity

to the

historically contingent

language

of the

original,

Alonso

required fidelity

to a

privileged

metachronic structure (ratio) discoverable

in the

text

but

unconstrained

by

history

and

expressible

in any

language. 'Reason (ratio)

is

common

to

every

people',

he

argued, 'though

it

is expressed

in

various idioms. So let

us

discuss

whether

the

Latin language supports

[a

translation],

. . .

whether

it

agrees

with

reality

(res

ipsae),

not

whether

it

accords with

the

Greek.' Alonso's

views

were compatible with

the

philosophical grammar

of

the later Middle

Ages

which, despite

its

unconscious commitments

to

Latin

as the

learned

lingua franca, attempted

to

expose timeless structures belonging

to

language-in-general

and

deriving somehow from reality.

His

thoughts also

foreshadowed

the

witty question

that

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola asked

later

in the

century

in his

debate with Ermolao Barbaro:

'Can

people

live

without hearts

if

they

are all

tongue (lingua),

are

they

not

then

. . .

simply

dead dictionaries (glosaria)V Pico meant

that

a

language, whose phonetic

41.

Birkenmajer 1922,

p.

189: 'interpretatio autem omnis recta,

si

Graeco respondet, vitiosa

si non

respondet. Itaque omnis interpretationis contentio unius linguae

ad

alteram est'; ibid.,

pp.

194,

204;

Bruni 1928,

p. 83;

Troilo

1931-2,

p. 383;

Harth

1968,

p. 46.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Translation, terminology and style

9i

properties make it a material entity, can

fall

short

of

the deeper, immaterial

thoughts it tries to express, which, so he argued, is why Pythagoras would

have

preferred to explain his philosophy through silence

rather

than

speech.

42

Pico

also wrote

that

Cicero

advised 'settling the thought

(mens) rather

than

the expression (dictio), taking care to guide the reason (ratio), not the

speech

(oratio)', but Bruni and most other humanists took the opposite

lesson

from

Cicero

and Quintilian

—

the primacy of oratio over ratio as the

distinctly human activity. Bruni consequently saw translation as a

transformatio

orationis, where oratio represented an indissoluble amalgam of

semantic and aesthetic values.

43

This implied

that

style (eloquentia, elegantia)

was

also a locus of correspondence between text and version, and it

stimulated the translator's own artistic ambitions. Bruni knew

that

Cicero

in his translations had rejected the duties of a mere go-between (interpres),

insisting on the orator's creative role.

Likewise,

Poggio

Bracciolini claimed

the rights of an author (scriptor) for himself as translator.

Valla

and Dolet

urged the translator not to reproduce but to improve upon the formal

qualities of the original, and Bruni compared his work to

that

of the poet,

sculptor or painter,

thus

attributing to the translator the artist's autonomy.

Introducing a revision of his Physics translation, Argyropulos advised

'transferring the author's sententiae but using a greater number

of

words

to

extend their meaning', and in his De anima Perion called himself 'an

interpreter and evaluator of words . . . not of content (res)'.

44

The

Ciceronian

Perion carried the oratorical ideal in translation to its extreme

by

confining

himself

to the philological dimension

of

the text and ignoring

its philosophical content, but most Renaissance translators regarded content

(res) as another locus

of

correspondence. Even

Argyropulos,

often dismissed

as a paraphraser, admitted

that

'both issues are rightly of concern to us . . .

42.

Birkenmajer 1922, p. 166: 'Ratio enim omni nationi communis est, licet diversis idiomatibus

exprimatur. An ergo Latina lingua toleret proprieque scriptum sit et rebus ipsis concordet, non an

Graeco

consonet, discutiemus'; Prosatori latini 1952, p. 820: 'qui, excordes, toti

sunt

lingua, nonne

sunt

mera, ut Cato ait, mortua glosaria?

Vivere

. . . sine corde nullo modo possumus'; ibid., pp. 810,

813-14;

Harth

1968, pp. 44-8; Ashworth

1974a,

pp. 26-7;

Apel

1963, p. 162.

43.

Prosatori latini 1952, p. 814: 'Tullius . . . sciebat

tarn

prudens quam eruditus homo, nostrum esse

componere mentem potius quam dictionem, curare ne quid aberret ratio, non oratio'; Chomarat

1981,1,

pp. 62-7;

Seigel

1968, p.

159;

Apel

1963, p.

171;

Kelley

1970a, pp. 28-9;

Harth

1968, pp. 43,

53-

44.

Garin 1951, p. 84: 'recte quidem sententias referentes auctoris, latius autem eas explicandas

pluribusque verbis'; Aristotle

1553a,

p. 100: 'Verborum enim in iis sum, non rerum, explanator

atque aestimator'; Platon etAristote

1976,

p. 363 (Cranz); Minio-Paluello

1972,

p. 268; Schwarz 1944,

p.

74; Cuendet 1933, p. 382; De Petris

1975,

p. 18; Gravelle

1972,

p. 281; Bruni 1928, pp. 83-6, 127;

Apel

1963, pp.

181-2;

Critical Prefaces 1950, p. 81.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

92

Translation, terminology and style

understanding of content . . . and elegance of language'. However, the

distinction between res and ratio as bases of translation remains unclear in

Renaissance theorists, and the meaning of terms as broad as these was

predictably slippery. To

Alonso

de Cartagena res could mean 'the reality

represented' by a text, while for Salutati it seems to have meant something

like

'style' as

well

as 'content'.

45

ORATORY

AND

STYLE

IN

PHILOSOPHICAL

DISCOURSE

Salutati's student Roberto Rossi prefaced his version of the Posterior

Analytics with an apologetic defence of style: 'How would it harm the

work',

he asked, 'if it were more pleasant?' By the end of the century,

eloquence

was better established as a value in philosophical translation. It

was

the

chief

motivation, for example, of Ermolao Barbaro's unfulfilled

plan for a complete Latin Aristotle, in which he would 'render all the works

and enhance them with as much clarity, taste and elegance as possible'.

46

Despite

elements of continuity between their work and

that

of their

medieval

predecessors, Renaissance translators constructed their sense of

style

in terms of historical polemic, against the backdrop of the regretted

decline

of antiquity into barbarity and the contemporary campaign to

recover

ancient culture. The obligation to translate philosophy was

given

in

the humanist programme, yet it was important

that

duty should not be

drudgery,

that

it should be an ennobling service to high culture. This is what

made Bruni's slogan of

transformatio

orationis so meaningful in its time. If

translation was akin to oratory, then it was fit work for the intellectual hero,

the orator, as

Cicero

and Quintilian had described him. But oratorical

translation also implied commitment to classical rhetoric, an approach to

language

which since the age

of

the sophists had possessed its own technical

baggage

as

well

as certain anti-philosophical impulses. Thus, when Bruni

obliged

the translator of Plato or Aristotle to render figures of speech

(jigurae dicendi) and embellishments (exornationes) as

well

as meaning, he had

in mind something

that

was profounder

than

prettification but also unlike

poetry.

47

45.

Argyropulos to Cardinal Delia Rovere in his second version of the De anima, cited by Minio-

Paluello

1972, p. 268: 'Utrumque curae non iniuria nobis est . . . rerum inquam notitia . . . et

elegantia linguae . . .';

Seigel

1968, pp.

116—17.

46.

Roberto Rossi's dedication

of

his version

of

the Posterior Analytics, c. 1406, cited in Garin

1951,

p. 60:

'Quod

si suavior etiam ilia fuisset, quid tamen in hoc opere detrimenti?'; ibid., p. 88: 'omnes

Aristotelis

libros converto, et quanta possum luce, proprietate, cultu exorno'; ibid., pp. 89-90.

47.

Seigel

1968, pp. 6-19,

31-62,

103; Bruni 1928, pp. 86-90,

133-4;

Harth

1968, pp. 53, 56, 58; De

Petris 1975, pp. 24-5.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Translation, terminology and style

93

But

since Boethius had set out to make a Latin Aristotle,

there

existed

another, anti-rhetorical strain of philosophical translation which feared a

view

like Bruni's as a

threat

to meaning.

Alonso

represented this other

tradition when he complained

that

one 'who think[s] to subjugate moral

meaning to eloquence, ... to subordinate the most involved arguments of

the sciences to the rules

of

eloquence,

does not understand

that

the rigour of

science

abhors the adding and subtracting of words

that

belongs to

charming persuasion'. Giovanni

Pico,

George of Trebizond, Johannes

Dullaert and others also represented it when they said

that

eloquence was

unnecessary or indeed undesirable in philosophical discourse.

48

There were

concomitant objections to pleasure as a goal of philosophical translation,

even

though in making their work enjoyable and easy to read the basic

motive

of

the humanist translators was pedagogic. In general, since oratory

was

meant to result in action, the persuasion

that

Alonso

distrusted was the

primary object of eloquence: translation must charm if it hopes to teach.

Moreover,

translation as

transformatio

orationis required an oratorical

education in language, letters and history. Bruni considered this humanist

curriculum an antidote to the barbarism of the schools, but a university

philosopher like Agostino

Nifo

worried

that

it would disqualify the young

for

the study

of

philosophy.

Bruni called the orator 'the agent

of

truth',

but

Pico

wished to exclude his rhetorical

arts

from philosophy because they

were

deceptive and beguiling.

49

These anxieties were justified.

Valla,

who

spoke

of'the great sacrament

of

Latin

speech' and referred to 'the eloquent

.

. . [as] pillars of the church', taught

that

'petty reasonings of dialec-

ticians . . . metaphysical obscurities and . . . modes of signification should

not be mixed up in sacred enquiries . . . since [the Fathers] did not lay the

foundations of their arguments on philosophy'. He and Erasmus and

Juan

Luis

Vives

gave authoritative

voice

to the anti-philosophical impulse in

oratorical humanism, which was muted by an older conviction, present

48. Birkenmajer 1922, p. 175: 'errorem illorum . . . qui

putant

sententiam moralem eloquentiae

subiugandam . . . qui scientiarum districtissimas conclusiones eloquentiae regulis subdere vult, non

sapit, cum verba addere ac detrahere ad persuasionis dulcedinem pertinet, quod scientiae rigor

abhorret'; Grabmann

1926—56,1,

pp. 443-4; Fubini

1966,

p. 339; Schwarz 1944, p. 76; Gravelle 1972,

p.

276; Schmitt 1984, § vm, p.

133;

Vives

1979a,

pp.

20—1;

Hubert

1949,

p. 229; George

of

Trebizond

1984,

p. 303. It should be noted (cf. Gray 1963, pp. 507—10)

that

in Pico's debate on eloquence with

Barbaro, elements of irony, satire and rhetorical convention make a consistently literal

interpretation of his remarks problematic.

49.

Bruni 1928, pp.

133-4:

'poetae quidem multa conceduntur, quo in re ficta delectet . . .; oratori

autem, qui est veritatis actor, haec superflua verborum adjunctio . . . fidem rebus . . . minueret

.

. .'; Prosatori latini

1952,

p. 808; Medioevo e Rinascimento

1955,1,

p. 362 (Garin); Hubert 1949, p. 216;

DePetris

1975,

pp.

16-17;

W. F. Edwards

1969,

p. 85o;Harth 1968, p. 43; Heath

1971,

pp. 31,40,63-

4;

Ashworth

1974a,

p. 22, 1976, p. 358;

Vives

1979a,

pp. 20-1.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

94

Translation, terminology and style

from Petrarch to Bruni and beyond,

that

rhetoric could join with

philosophy in a practical, persuasive wisdom.

50

The

source of this belief, of course, was

Cicero,

whose philosophical

authority seemed as compelling to the humanists as

that

of Plato or

Aristotle.

They were aware of Cicero's achievements in translating Greek

philosophy and in creating a Latin philosophical terminology; his success

proved to them

that

his Latin was an adequate vehicle for philosophy.

Eventually,

however, the doctrinaire Ciceronianism

that

Erasmus ridiculed

and the dissatisfaction of professional philosophers with Ciceronian

versions more elegant

than

clear (Perion's De

anima

required a glossary in

more familiar Latin) betrayed the shortcomings of the oratorical style.

51

Censuring

Cicero

for confusing Aristotle's ivreXex^ta ('actuality') with

ivSeAexeLCL

('continuity'), Argyropulos went so far as to challenge the

competence

of

the master himself. Yet it was Cicero's professed admiration

for

Aristotle's eloquence

that

stimulated humanist translation

of

his works.

Unaware

that

Cicero

had found his 'golden stream of eloquence' in

Aristotle's

lost exoteric writings, Bruni and many others concluded from

his approval of Aristotle

that

the Stagirite's works had been ruined by the

barbarians and

that

his eloquence must be restored. Petrarch and George of

Trebizond, however, were ambivalent about the excellence of Aristotle's

style

or the best way to

translate

it, and others simply denied

that

he was

eloquent.

Valla

found his terminology in need

of

reform.

Vives

accused him

of

obscurantism. On the beauty

of

Plato's language consensus was stronger,

though George of Trebizond, warning

that

'too much . . . verbal

embellishment and ostentatious writing destroy all solemnity', noted

that

the Parmenides was denser and more concise

than

other dialogues.

52

50. Prosatori latini 1952, p. 596: 'Magnum ergo latini sermonis sacramentum . . . magnum profecto

numen . . . sancte ac religiose per tot saecula custoditur . . .'; p. 620: 'qui ignarus eloquentiae est,

hunc

indignum

prorsus

qui de theologia loquatur existimo. Et certe soli eloquentes. . . columnae

ecclesiae

sunt

. . .'; Renaissance Philosophy: New Translations, pp. 23-4 (L.

Valla,

'In praise of St

Thomas Aquinas'); Erasmus 1965, p. 190; Gray 1965, pp. 39-40, 45;

Apel

1963, pp.

184-5;

Chomarat

1981,1,

pp. 166, 188, 446-9, 602, 680-1,

11,

pp. 799,

1123-8;

Harth

1968, p. 63;

Seigel

1968,

pp. 6—19,

31-62,

103.

51.

Bruni 1928, p.

116;

Medioevo e Rinascimento

1955,1,

pp. 343, 355 (Garin);

Seigel

1968, pp. 4,

101-3;

L.

Jardine

1977, p. 149; Schmitt 1983a, p. 74; Birkenmajer 1922, p. 174; Platon et Aristote 1976, pp.

364-5 (Cranz) and pp. 383-4 (Stegmann); Erasmus 1965, pp.

xxxii-xlix;

Ebel 1969, p. 599.

52.

George of Trebizond 1984, p. 303: 'Verborum enim

ornatus

et compositionis pompa, si latius

confluat. . . omnem gravitatem suam infringit'; Medioevo e Rinascimento

1955,1,

pp. 349, 353, 363,

373 (Garin); Bruni

1741,1,

pp.

15-17;

Cicero,

Tusculan Disputations 1.10.22 and Academica

11.38.119;

Bruni 1928, pp. 45-8, 74; Cammelli

1941-54,11,

pp. 176-80; Birkenmajer 1922, p. 158; Garin 1951,

pp. 57-8; Prosatori latini 1952, p. 58; Minio-Paluello

1972,

p. 265; Breen 1968, pp. 30-1;

Seigel

1968,

pp.

31-62,

no,

121-2,

i35;Gravelle

1972,

pp. 275, 283-5;

Vives

1979»,

pp. 37-9; Camporeale 1972,

p.

229; Chomarat

1981,1,

p. 233; Platon et Aristote 1976, pp. 378, 388 (Stegmann); Schmitt 1983a,

p.

80; Hankins 1983, p. 102.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Translation, terminology and style

95

In general, the

effect

of the recovery and publication of Greek

philosophical texts was to encourage translations of them

that

were more

sensitive to classical Latin style

than

the efforts of medieval scholars. This

new emphasis on style was as much a result of

attitudes

towards the Greek

language as of progress in Latin philology.

Like

the ancient Romans they

admired, even those humanists who considered Latin the equal

of

Greek

or

its superior described the rival tongue in

terms

that

hinted admiration for its

powers.

If Greek was prolix, it was also rich in words; if it was abstract, it

was

also a good tool for formal analysis. All this loose comparison, however

misguided or narrowly motivated, focused the

translator's

attention

on the

formal properties of Greek and on means for achieving comparable or

compensating stylistic effects in Latin translation.

Valla,

who passionately

preferred Latin to Greek, maintained

that

it was a

better

medium for

philosophy because it was concrete and

that

many perplexities in

logic

could

be traced to the absence of this quality in Greek. The Byzantine

George

of

Trebizond was equally

ardent

for the pre-eminence

of

his native

tongue, and even Pier Candido Decembrio, an Italian, conceded

that

Aristotle

'explains weighty issues with words of such brevity

that

Latin

words can scarcely do justice to his Greek terms, which carry more

meaning'. Greek became inevitable in the humanist curriculum, and some

claimed

that

it was indispensable for philosophy. Writing in 1520, by which

time humanists had Latinised the whole Aristotelian corpus, Thomas More

told Martin Dorp

that

'Aristotle himself . . . could not be completely

known to you without a command of Greek letters . . . for nothing

of

his

has been so aptly translated

that

it would not

better

penetrate

the mind

if

it

were heard in his own words.'

53

More's ideal was not realised. While a

university philosopher

like

Jacopo Zabarella might have a good command

of

Greek,

among his colleagues it was not a universal

attainment.

In Oxford

John

Case found Hellenists to consult, but he apologised for his own Greek

in trying to find stylistic grounds for calling the second book of the

Oeconomics

spurious. Philosophers commonly taught from Greek texts by

the middle of the sixteenth century, but they also continued to buy

Greekless

Thomistic commentaries. Some reasons for the slow penetration

53.

Hankins 1983, p.

130,11.

84: 'Ceterum res ponderosas adeo brevissimis verbis explicatPhilosophusut

vix

verba latina satisfaciant graeca quae significantiora

sunt';

ibid., pp. 96, 103;

Vives

1979a,

p. 192:

'Ad

Aristotelem ipsum venio . . . Hie ergo ipse non poterit

totus

tibi sine Graecarum peritia

litterarum

innotescere . . . quod nihil eius

tarn

commode versum est ut non idem ipsum suis ipsius

verbis acceptum in pectus influat potentius'; Bruni 1928, pp. 102-4; Baron 1966, pp. 284-5; Garin

1951,

p. 70; Camporeale 1972, pp. 173,

176-7;

Gravelle 1972, pp. 269-74, 281-4; Breen 1968, p. 10;

George

of Trebizond 1984, pp. 143, 160,

191-2.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

9

6

Translation, terminology and style

of

Greek

into the general world

of

philosophical discourse are evident. The

first group of Byzantines who brought Greek to the Italians might have

been regarded as incompetent Latinists even if they had succeeded in

mastering the language. Such prejudice reinforced a facile

distrust

of

Greek

that

went back to Petrarch and to Cato and was sustained by the absence of

adequate

lexical

and grammatical material through the fifteenth century.

Substitutes as poor as the

Graecismus

of Eberhard de Bethune or the

Derivationes

of Uguccione da Pisa could only deepen the unease of Italian

scholars whose Latinity began to grown refined in the fourteenth

century.

54

TERMINOLOGY,

TRANSLITERATION

AND

NEOLOGISM

When preparing Chrysoloras'

trip

to Florence, Salutati had urged a protege

studying with Manuel in Constantinople to 'bring as many

lexical

writers

(yocabulorum

auctores)

as can be obtained', but systematic help came

slowly.

Working

without the reference tools

that

modern scholars take for granted,

Traversari nearly despaired of his translation of Diogenes Laertius: 'One

stumbles into such a forest of terminology, . . .

that

I am almost without

hope

of

finding Latin words

that

translate

the Greek and are fit for the ears of

a learned reader.'

55

George of Trebizond encountered similar difficulties

with

Aristotle, but Bruni, whose experience as a

translator

was certainly

extensive,

struck a different pose:

I do not see how Latin letters are surpassed by Greek . .

.

Even

if

the Greek are richer

than

ours, how does this prevent us from saying elegantly in Latin just what was said

in Greek if, instead

of

chasing words like boys in a game, we

follow

the meanings of

what is said

(sententiae

dictorum)?

If

they can express anything in more

ways

than

we

can, this is actually a kind of superfluity and profusion, but our Latinity . . .

certainly has its tools and equipment, not profuse, to be sure, but powerful and

abundantly sufficient to every need.

Brum's dispute with

Alonso

de Cartagena, wherein he spent pages on the

proper rendering

of

raya&ov

(see above, pp. 89—90), testifies to his sensitivity

to philosophical diction, but his use above of the game metaphor, which

implies

that

words are secondary tokens in the

Sprachspiel,

reveals a contrary

and eirenic inclination to forget mere verbal differences as philosophically

54.

W. F. Edwards 1969, p. 844; Schmitt 1983b, p. 178; Stinger 1977, p. 103; B. Bischoffi96i, pp. 215-

16;

Chomarat 1981, pp.

209-11;

see below, p. 107.

55.

Salutati to Jacopo d'Angelo della Scarperia, cited in Cammelli

1941-54,

1, p. 33: 'Platonica velim

cuncta tecum portes et vocabulorum auctores quot haberi possunt . . .'; Traversari 1759, p. 310:

'Tanta illic offenditur vocabulorum silva, ac praecipue in explicandis disciplinis, ut fere desperem

Latina repeririposse, quae Graecis reddita erudito lectoriaures impleant'; Ullman 1963, pp.

118-24;

De

Petris 1975, p. 20; Stinger 1977, p. 72.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008