Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

v. Florida (1961) that gender discrimination in jury selection did not vio-

late constitutional rights and that women had responsibilities in the home

that held precedence over jury duty. In Taylor, the Court pointed to

women’s labor force participation as evidence that women’s lives and re-

sponsibilities were not limited to the home.

At that time in Louisiana, a woman could not be selected for jury

duty unless she had filed a written declaration of her desire to be a juror.

In this case, Billy Taylor had been indicted for kidnapping, but because

there were no women on the jury, he claimed that he would be deprived

of “a fair trial by a jury of a representative segment of the community.”

Although Louisiana’s system did not disqualify women, the Court

wrote: “Louisiana’s special exemption for women operates to exclude

them from petit juries, which in our view is contrary to the commands of

the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.” The decision ended the gender

discrimination in jury selection that women had fought since the Seneca

Falls Convention in 1848 and more consistently attempted to end since

the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment granting women suffrage

rights in 1920.

See also Fourteenth Amendment; Hoyt v. Florida; Juries, Women on;

Nineteenth Amendment; Seneca Falls Convention

References Ginsburg, “Gender in the Supreme Court: The 1973 and 1974

Terms” (1976); Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975).

Temperance Movement, Women in the

Women’s involvement in the temperance movement began in the 1840s,

a time when married women’s legal dependence upon their husbands

made them financially vulnerable. An alcoholic husband could consume

not only his income and financial resources but his wife’s as well, leaving

her and her children destitute. Several temperance organizers also became

women’s rights advocates after concluding that without political power

they had little hope of accomplishing their goals. The temperance move-

ment prompted the founding of the first newspaper edited and published

by a woman in the United States, The Lily: A Ladies Journal Devoted to

Temperance and Literature. Founded in 1849 by Amelia Bloomer in

Seneca Falls, New York, The Lily added women’s rights to the issues it ad-

vocated. Other early temperance leaders who became women’s rights

leaders include Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Eliza-

beth Cady Stanton.

In the 1870s, the temperance movement entered a new phase with

the formation of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

Under the leadership of Frances Willard, WCTU president from 1879 to

1898, the WCTU expanded its agenda to include advocacy for woman

Temperance Movement, Women in the 659

suffrage. Women in the WCTU and other organizations significantly con-

tributed to the passage in 1917 and the ratification in 1919 of the Eigh-

teenth Amendment prohibiting alcohol in the United States.

In 1929, Pauline Sabin of New York called together two dozen

women and formed the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition

Reform (WONPR), dedicated to the repeal of the Eighteenth Amend-

ment. WONPR advocated temperance and argued that Prohibition had

increased alcohol use, crime, and political corruption in addition to con-

tributing to the general disregard for the law. By the 1932 elections, the or-

ganization had more than 1 million members, who through grassroots

networks and state and national organizations pressured political candi-

dates to support repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. WONPR endorsed

candidates, generally Democrats, and campaigned for them. After Con-

gress passed the Twenty-first Amendment repealing the Eighteenth

Amendment, WONPR members helped organize state ratification con-

ventions. The process was completed in less than a year.

See also Anthony, Susan Brownell; Bloomer, Amelia Jenks; Coverture; Mott,

Lucretia Coffin; Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Stone, Lucy

References Flexner and Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights

Movement in the United States, enlarged edition (1996); Kyvig, “Women against

Prohibition” (1976).

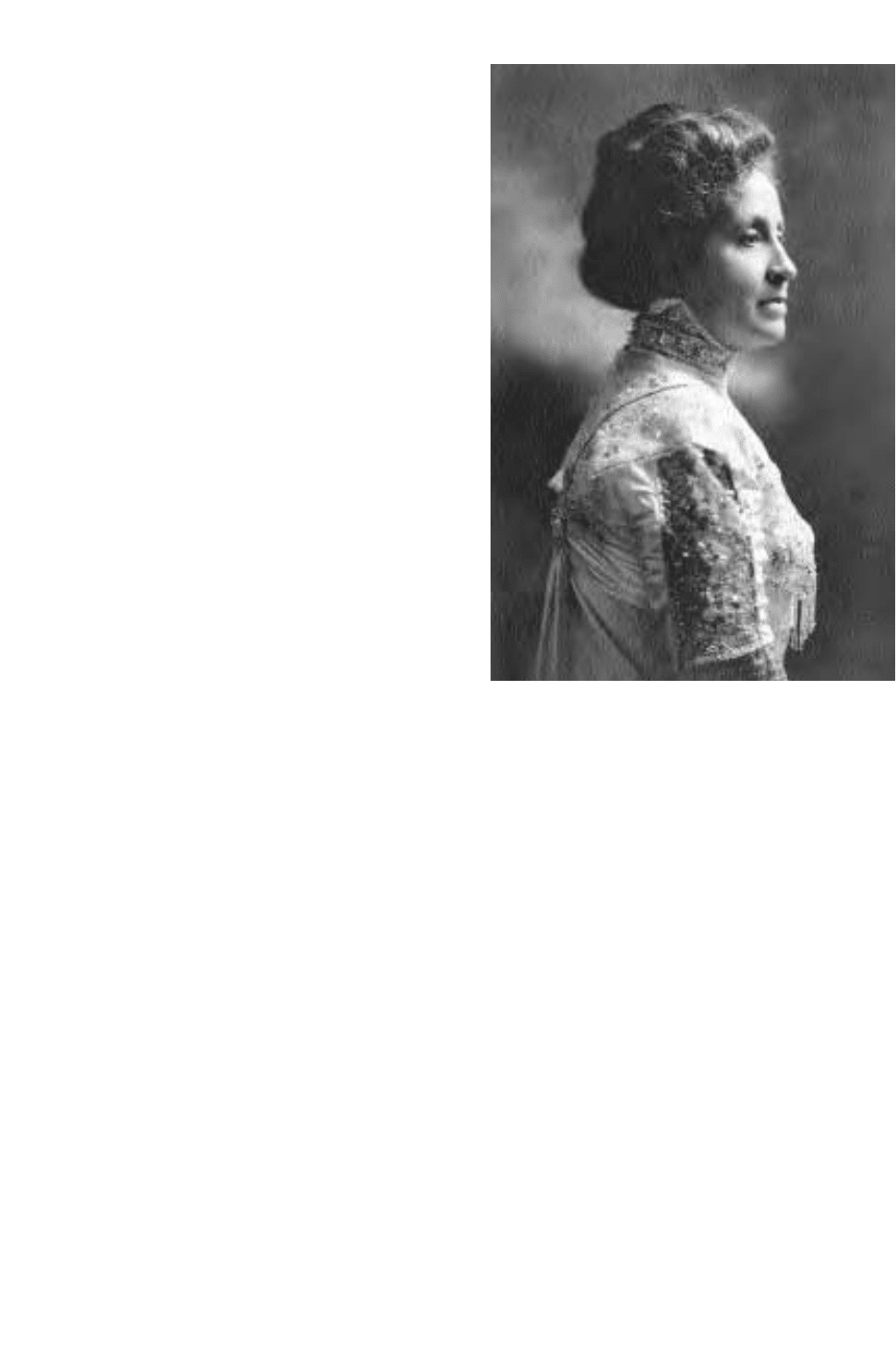

Terrell, Mary Eliza Church (1863–1954)

Lecturer, political activist, and educator Mary Church Terrell committed

herself to improving the lives of African American women. She served as

the first president of the National Association of Colored Women

(NACW) and led the new organization’s development of its programs. In

1909, she helped found the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People. In the 1940s, she provided leadership in a successful ef-

fort to desegregate restaurants in Washington, D.C.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, Mary Church Terrell was born the same

year that President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclama-

tion, freeing African Americans from slavery, including Terrell’s parents.

Wanting a good education for their daughter, her parents sent her from

Memphis, Tennessee, with its segregated schools, to an elementary school

associated with Antioch College in Ohio. She attended Oberlin Academy

during her high school years and earned her bachelor of arts degree in

1884 and her master of arts degree in 1888, both from Oberlin College.

She also taught from 1885 to 1888. Traveling in Europe with her father in

the late 1880s, Terrell studied languages, learning French and German.

She married Robert H. Terrell in 1891 and became a homemaker be-

cause married women could not teach in public schools, although she did

660 Terrell, Mary Eliza Church

teach in the Colored Women’s League’s

night school. In 1895, Terrell received an

appointment to the District of Columbia

Board of Education, making her one of the

first African American women on a U.S.

school board. She later served again on the

board from 1906 to 1911.

Terrell began her long association

with women’s clubs in 1891, joining the

Colored Women’s League of Washington,

D.C. (CWL), which sought to improve

black women’s lives. In 1896, the CWL and

the National Federation of Afro-American

Women, an association of local black

women’s clubs, merged into the National

Association of Colored Women (NACW)

and elected Terrell president. NACW was

the first national network of communica-

tion among black women, providing them

with information about events across the

country.

African American women had begun

forming women’s clubs at about the same time as white women, but

African American women had to form their own associations because of

the racial prejudice of white women who did not permit them to partici-

pate in their clubs. The extent of the prejudice is apparent from an event

in 1900. When the General Federation of Women’s Clubs held its conven-

tion, Terrell was denied the opportunity to offer them greetings on behalf

of NACW because of the objections of southern white women.

As president of NACW, Terrell established the organization’s

monthly newsletter, National Notes, organized biennial conventions with

art and literature exhibits, and trained women in leadership. She encour-

aged local clubs to create kindergartens and day nurseries, and she raised

the money to hire a kindergarten adviser to motivate and help clubs open

them. More than a dozen facilities had opened by 1901. She also led the

formation of Mother’s Clubs, which taught housekeeping and child-rear-

ing skills. Several clubs also opened homes for girls. Terrell stepped down

in 1901 because the NACW constitution prohibited anyone from serving

more than two consecutive terms.

By the mid-1890s, Terrell had become a professional lecturer, speak-

ing at Chautauquas, forums, and universities across the nation. In the

course of her travels she encountered the South’s segregation laws and the

Terrell, Mary Eliza Church 661

Mary Church Terrell,

first president of the

National Association

of Colored Women,

fought against

segregation and

lynching, ca. 1890

(Library of Congress)

inhumanity of them. Those experiences led to her commitment to inter-

racial understanding and her conviction about the importance of com-

munication between the races. She wrote articles about the accomplish-

ments of African Americans, criticized the white press for its stereotypical

articles about blacks, and attempted to educate whites about blacks and

their lives. She decried lynching and exposed the lies behind the myth that

black men were lynched in retaliation for raping white women, and she

described the inhumanity of the convict lease system.

During World War I, Terrell helped support the war effort by work-

ing at the War Risk Insurance Bureau but was dismissed because of her

race. She then went to work at the Census Bureau, but the humiliation of

the federal government’s segregation policies led her to resign the position.

Terrell was also active in other political movements. She had met suf-

frage leader Susan B. Anthony in 1898, and the two women had become

friends. Even though she was aware of the racism within the suffrage move-

ment, she lectured on the topic and worked for passage of the woman suf-

frage amendment. After ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, she

worked for the National Republican Committee as the director of black

women in the eastern division. From 1929 to 1930, Terrell organized black

women for Ruth Hanna McCormick’s campaign for the U.S. Senate.

After World War II, Terrell changed the emphasis of her work from

racial understanding to a more militant approach. In 1946, she applied to

the District of Columbia chapter of the American Association of Univer-

sity Women (AAUW), was rejected on the basis of race, and appealed to

the organization’s national board, which decided in Terrell’s favor. In

1948, AAUW approved a new national bylaw that prohibited discrimina-

tion on the basis of race, religion, or politics. Terrell and two other African

American women joined the District of Columbia chapter in 1949.

She began another desegregation campaign in 1949. The district had

passed laws in the 1870s requiring service in public accommodations re-

gardless of color, but when the district’s legal code was written in the

1890s, the laws were disregarded and segregation became the norm. Re-

search showed that the laws had not been repealed, and Terrell formed a

committee to enforce the district’s antidiscrimination laws. As chair of

the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of District of Colum-

bia Anti-Discrimination Laws in 1949, she recruited the support of labor,

religious, women’s, and civic organizations. In 1950, an interracial party

of four requested service at Thompson’s Restaurant, but the three black

people in the group were not permitted to purchase food. They filed a

complaint that the municipal court dismissed. The next year, Terrell led a

sit-in at Kresge’s lunch counter, and after six weeks, the management

changed its policy and began serving African Americans. The same year,

662 Terrell, Mary Eliza Church

Terrell led a boycott and a picket line at Hecht Company, a department

store that had segregated lunch counters. After four months, the manage-

ment capitulated. Terrell was ninety years old when she led these and

other demonstrations in the District of Columbia. In 1953, the U.S.

Supreme Court decided in District of Columbia v. John Thompson, the

owner of the first restaurant that had refused Terrell and her party ser-

vice, that the laws from the 1870s were in force, and the district began to

be desegregated.

Ter rel l wrote The Progress of Colored Women: An Address Delivered

before the National American Woman Suffrage Association (1898), Harriet

Beecher Stowe: An Appreciation (1911), Colored Women and World Peace

(1932), and A Colored Woman in a White World (1940).

See also American Association of University Women; Anthony, Susan Brownell;

Civil Rights Movement, Women in the; National Association of Colored

Women; Suffrage

References Jones, Quest for Equality: The Life and Writings of Mary Eliza Church

Terrell, 1863–1954 (1990).

Thomas, Lera Millard (1900–1993)

Democrat Lera Thomas of Texas served in the U.S. House of Representa-

tives from 26 March 1966 to 3 January 1967. When her husband died in

office, Lera Thomas won the special election to fill the vacancy. During

her brief tenure in Congress, Thomas sought appropriations for a labora-

tory in Houston and for the Houston Ship Channel, both projects that her

husband had advocated. She did not run for another term.

Born in Nacogdoches, Texas, Lera Thomas attended Brenau College

and the University of Alabama. In 1968, Thomas was special liaison for

the Houston Chronicle to members of the armed forces in Vietnam.

See also Congress, Women in

References Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, Women in

Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

Thompson, Ruth (1887–1970)

Republican Ruth Thompson of Michigan served in the U.S. House of Rep-

resentatives from 3 January 1951 to 3 January 1957. Congresswoman

Thompson worked for public library services in rural areas, programs to

stimulate the growth of low-cost electric power from a variety of sources,

and the establishment of a Department of Peace. Her other interests in-

cluded flood control and drainage projects. Thompson was defeated in

the 1956 primary election.

Born in Whitehall, Michigan, Ruth Thompson graduated from

Thompson, Ruth 663

Muskegon Business College in 1905. From 1918 to 1924, she worked in a

law office and studied law at night.

Elected probate judge in Muskegon County, she served from 1925 to

1937. After serving in the Michigan House of Representatives from 1939

to 1941, she worked in the civilian personnel section of the adjutant gen-

eral’s office from 1942 to 1945 and served in the adjutant general’s bureau

at Headquarters Command in Frankfurt, Germany, and Copenhagen,

Denmark, in 1945 and 1946. She returned to private law practice in 1946.

See also Congress, Women in; State Legislatures, Women in

References Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, Women in

Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

Thornburgh v. American College of

Obstetrics and Gynecology (1986)

In Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the U.S.

Supreme Court rejected four provisions of the Pennsylvania Abortion

Control Act of 1982 on the basis that they subordinated a woman’s privacy

interests and concerns in an effort to dissuade her from having an abor-

tion. The invalidated provisions called for a physician to tell a woman

seeking an abortion that the father had a financial responsibility for the

support of a child and that medical assistance could be available if she

chose to continue the pregnancy. The physician was also required to in-

form the woman of any physical, medical, or psychological risks involved

in the abortion. Another rejected provision required the physician to re-

port the identity of the physicians involved in the procedure and infor-

mation that would permit the ready identification of the woman who had

the abortion. The last provision required, in postviability abortions, that

two physicians be in attendance; in addition, the physicians had to use the

abortion technique most likely to preserve the life of the fetus, even if it

placed the woman at risk, and there was no exception for emergency abor-

tions, which also placed the woman’s life at risk.

The Court overturned part of Thornburgh when it decided Planned

Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) and permitted

states to require informed consent.

See also Abortion; Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health; Bellotti v.

Baird; Bray v. Alexandria Clinic; Colautti v. Franklin; Doe v. Bolton; Harris v.

McRae; Hodgson v. Minnesota; Ohio v. Akron Center; Planned Parenthood

Association of Kansas City, Mo. v. Ashcroft; Planned Parenthood of Central

Missouri v. Danforth; Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v.

Casey; Poelker v. Doe

References Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 476

U.S. 747 (1986).

664 Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Thurman, Karen L. (b. 1951)

Democrat Karen Thurman of Florida entered the U.S. House of Repre-

sentatives on 3 January 1993. Congresswoman Thurman has worked to

apply the concepts of risk assessment and cost benefit analysis to govern-

ment decisions and to lift the burden of unfunded federal mandates from

state and local governments. She has advocated changes in the Medicaid

funding formula to better reflect a state’s needs and has sought to reim-

burse Florida for the costs associated with its immigrant population.

Thurman supports reproductive rights and reduction of the budget

deficit by cutting outmoded military projects and increasing taxes on for-

eign corporations. She opposed the North American Free Trade Agree-

ment (NAFTA) because the citrus and peanut crops grown in her area

compete with Mexican products, and thus NAFTA created an economic

threat to farmers in her district.

Thurman served on the Dunnellson City Council from 1975 to 1983

and was mayor from 1979 to 1981. She served in the Florida Senate from

1983 to 1993, where she worked on environmental issues. She called for

greater use of solar energy and worked to clean up leaky underground pe-

troleum tanks, and she sought to protect Florida’s drinking water and pre-

serve wetlands. She also worked on consumer protection and education.

Born in Rapid City, South Dakota, Thurman earned her associate’s

degree from Santa Fe Community College in 1971 and her bachelor of

arts degree from the University of Florida in 1973.

See also Congress, Women in; Reproductive Rights; State Legislatures, Women

in

References Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America 1994 (1993);

www.house.gov/thurman/about.htm.

Triangle Shirtwaist Company Fire

On 25 March 1911, the muffled sound from an explosion in New York

City’s Asch Building was the first indication of the fire in which 145

women employees of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company died. After the ex-

plosion, smoke billowed from windows on the eighth floor, and flames

soon followed. People on the street watched in horror as the only fire es-

cape collapsed with women climbing down it. The fire moved so quickly

that some women died at their sewing machines, and other women died

trying to escape through an exit door that was locked. Still other women

died from jumping out of the building.

The building owners and the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Com-

pany had been alerted to the many fire hazards that existed at their prop-

erty. Flammable materials were scattered on the floor, doors opened in-

ward, the stairwells were narrow and drafty, and the building had no

Triangle Shirtwaist Company Fire 665

sprinklers. The company owners were tried for manslaughter and were

found not guilty.

One of those who witnessed the fire was Frances Perkins, who served

as a chief investigator for the Factory Investigation Commission that was

formed after the fire. The commission’s recommendations included pass-

ing a fifty-four-hour workweek and a new industrial code, both of which

New York enacted.

See also Perkins, Frances (Fanny) Corlie

References Wertheimer, We Were There: The Story of Working Women in

America (1977).

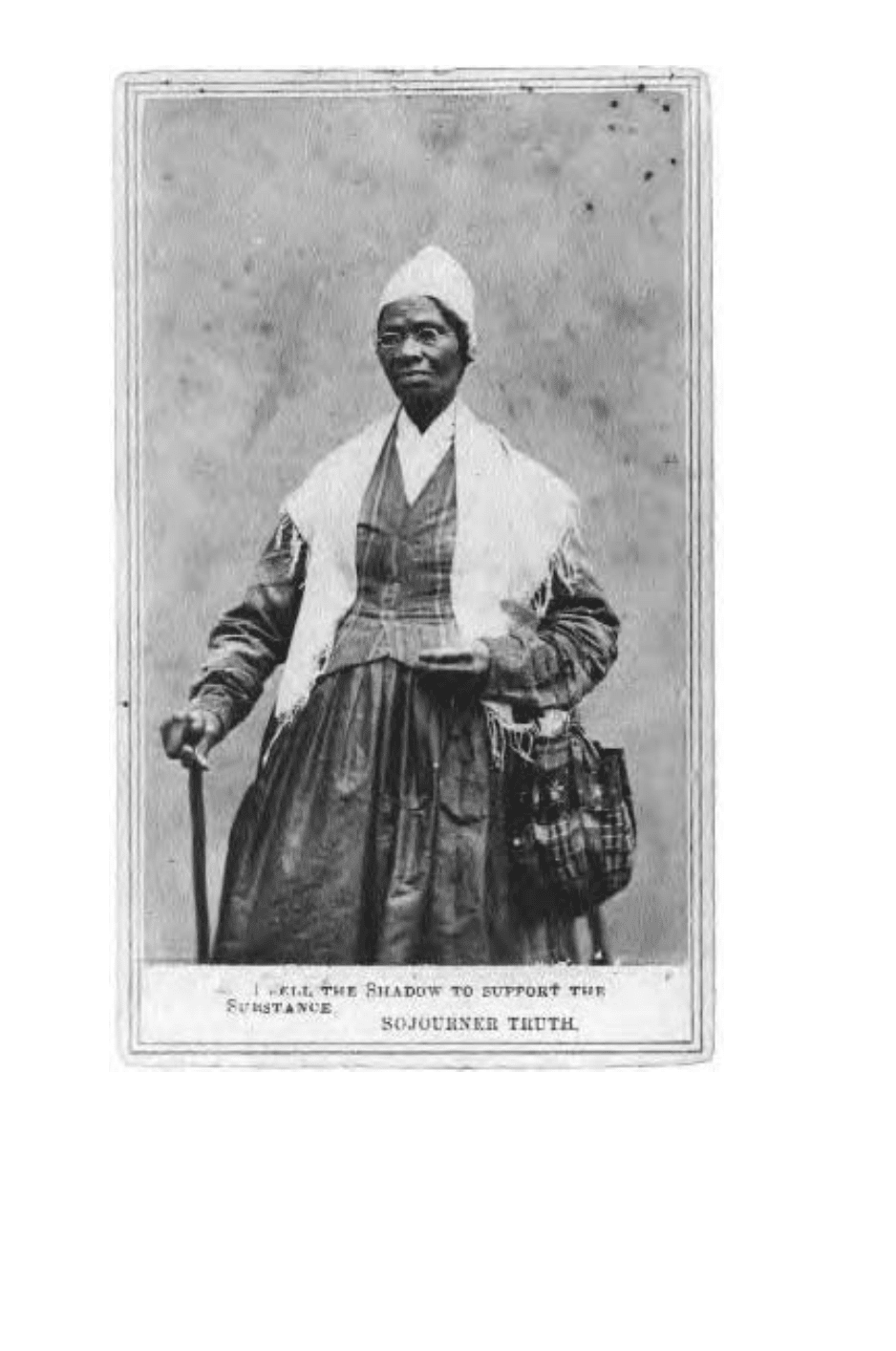

Truth, Sojourner (ca. 1797–1883)

African American Sojourner Truth made herself a force in nineteenth-

century reform movements, denouncing slavery and slavers and advocat-

ing freedom, women’s rights, woman suffrage, and temperance. An illiter-

ate itinerant preacher, she helped propel the reform movements on which

she centered her life.

Sojourner Truth’s names reveal much about her. Born a slave in Hur-

ley, New York, and given the name Isabella, she took the name of the Van

Wagener family who bought her freedom when she was an adult, as well

as her youngest child’s freedom. The last shackles of slavery ended when

New York abolished it on 4 July 1827. Religious experiences beginning in

1827 endowed her with the power of the Holy Spirit and transformed her

into a powerful and moving preacher. In 1843, on the day of Pentecost, she

changed her name to Sojourner Truth, which means “itinerant preacher.”

While living at a religious commune in Massachusetts, Sojourner

Truth met Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and other reform

leaders and became part of a network of antislavery activists. She made

her first antislavery speech in 1844 and appeared at her first large women’s

rights meeting in 1850. She helped support herself by selling copies of her

autobiography, Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave Emanci-

pated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York, in 1828.

Sojourner Truth’s speech at the 1851 Ohio Women’s Rights Conven-

tion, commonly known as her “Ain’t I a Woman” speech, contributed to

her growing national celebrity and her stature as a symbol of strength and

leadership. Some circumstances on the day of the speech and her words

may have been enhanced by the desire to make her an even more dramatic

figure than she was in reality. The traditionally accepted version of the

speech and its circumstances was written twelve years after the event. It

places her in a hostile crowd, has her speaking in dialect, and includes the

refrain “and ain’t I a woman?” But she may not have used the phrase. An

article published in the Salem Anti-Slavery Bugle on 21 June 1851 offered

666 Truth, Sojourner

a different account, which was written by the convention secretary and is

the one that Sojourner Truth’s most recent biographer regards as the more

accurate. Although she may have spoken in dialect, the story does not re-

flect that. In addition, the audience was not hostile, and the article does

not include any references to “and ain’t I a woman?” In part, the Anti-Slav-

ery Bugle report reads:

Truth, Sojourner 667

Sojourner Truth,

preacher and aboli-

tionist, participated

in many suffragist

conventions and be-

came famous for her

“Ain’t I a Woman”

speech, ca. 1850s

(Library of Congress)

I have as much muscle as any man, and can so as much works

as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped

and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard

much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any

man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as

man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say, is a woman have

a pint and man a quart—why cant she have her little pint full?

You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take

too much,—for we cant take more than our pint’ll hold. The

poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to

do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and

you will feel better.

The reporter concluded with “The power and wit of this remarkable

woman convulsed the audience with laughter.”

After the Civil War, a rancorous debate developed over the wording

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It included the

word male, which white feminists wanted removed. The debate continued

when the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing suffrage to former slaves

was introduced and did not extend the right to women. Most male and

black abolitionists, saying it was the “Negro’s hour,” did not want to im-

peril black men’s suffrage by adding references to woman suffrage. Truth

joined white feminists, arguing that if black men could vote, but black

women could not, “colored men will be masters over the women, and it

will be just as bad as it was before.” When the women’s rights movement

split into two camps, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA)

and the National Woman Suffrage Association, however, Truth aligned

herself with the more conservative AWSA, which supported the Four-

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Until her death, Sojourner Truth remained active in public affairs,

primarily serving as an advocate for new arrivals in Washington, D.C.,

who had been slaves. She worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau and with

private relief agencies. She also developed a plan to help freed people

move to Kansas but was unable to convince Congress to support it. In

1879, however, the state became the destination for many African Ameri-

cans from the Deep South.

See also Abolitionist Movement, Women in the; Fifteenth Amendment; Four-

teenth Amendment

References Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol (1996).

Tubman, Harriet (ca. 1820–1913)

Harriet Tubman escaped slavery and made at least nineteen trips from the

North into the southern slave states to conduct more than 300 slaves into

668 Tubman, Harriet