Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

• Senate president pro tempore: Democrat Louise Holland Coe,

New Mexico, 1931

• Senate president: Republican Consuelo Northrop Bailey,

Vermont, 1955

Between 1895 and 1921, the number of women serving in state leg-

islatures was uneven, declining to no women in 1905 and 1907, until 1923,

when small increases became a weak pattern. In the years from 1923 to

1971, growth was steady but again slow. It was not until 1971 that women

made up 4.5 percent of all legislatures. Significant growth in the number

of women in state legislatures appeared in the mid-1970s, suggesting that

the modern feminist movement influenced the number of women run-

ning for and winning seats.

Even with the growth, however, only 22.3 percent of all state legisla-

tors (1,652 female state legislators out of 7,424 total state legislators) were

women in 1999, more than seventy-five years after women gained suffrage

rights. In 1999, the state of Washington had the highest percentage of

women (40.8 percent) in its legislature, followed by Nevada with 36.5 per-

cent and Arizona with 35.6 percent. Alabama had the lowest percentage of

women, with 7.9 percent; Oklahoma had the next lowest percentage, with

10.1 percent; and Kentucky had 11.6 percent. In 1999, Arkansas’s state

Senate was the only legislative body that had no women serving in it. Of

the women serving in state legislatures in 1999, African American women

held 166 seats, Asian American/Pacific Islander women held seventeen

seats, Latinas held forty-eight, and Native American women held eleven.

The significance of women serving in state legislatures rests in the

additional perspectives that women bring to decisionmaking and the dif-

ferences in priorities between women and men, regardless of party affili-

ation. For example, women’s top-priority bills more frequently deal with

health and welfare issues than men’s top-priority bills. Women tend to de-

velop expertise in the areas of health and welfare, whereas men tend to de-

velop expertise in fiscal matters. In addition, the higher the proportion of

women legislators, the more likely that women’s priority bills will deal

with women, children, and families and the more likely that they will win

passage. Women legislators have worked for and won changes in rape leg-

islation and social welfare, child care, family violence, divorce, and educa-

tion policies. Women have also offered and advocated changes in other ar-

eas, including tax policy, the environment, economic development,

transportation, and agriculture. By adding to the pool of ideas and knowl-

edge, women alter the legislative agenda and expand the options for solv-

ing identified problems and for initiating legislative action.

In addition, state legislatures often provide the base from which both

State Legislatures, Women in 639

female and male candidates for higher office begin their political careers.

For example, of the fifty-six women serving in the 106th Congress

(1999–2001), twenty-nine had first served in state legislatures.

See also Bosone, Reva Zilpha Beck; Fauset, Crystal Dreda Bird; Mink, Patsy

Matsu Takemoto

References Center for the American Woman and Politics, National Information

Bank on Women in Public Office, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers

University; Cox, Women State and Territorial Legislators, 1895–1995 (1996);

Thomas, How Women Legislate (1994).

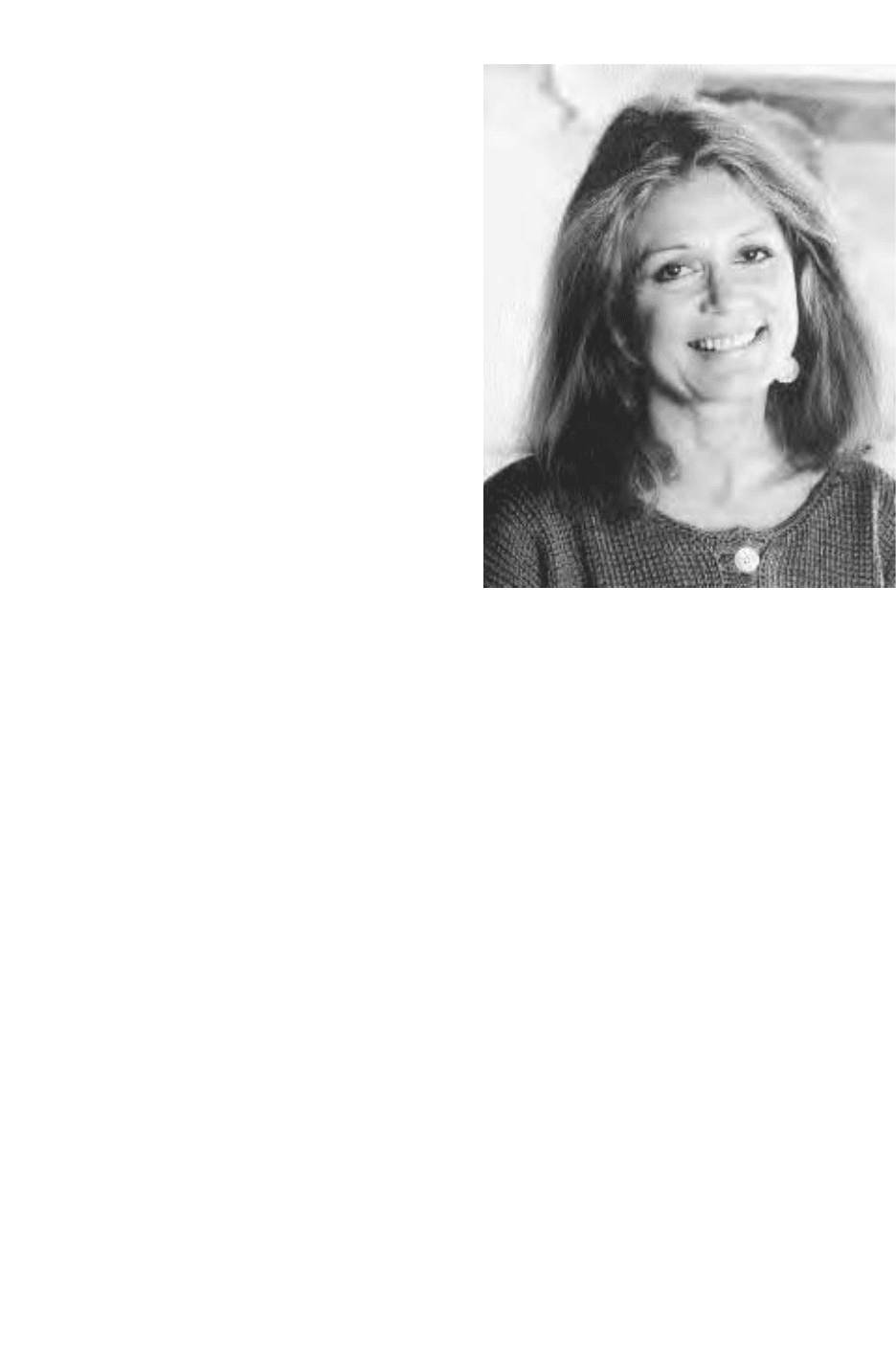

Steinem, Gloria Marie (b. 1934)

Feminist, journalist, author, and founder of Ms. magazine Gloria

Steinem’s involvement in feminist activities began in the early 1960s. A dy-

namic speaker, Steinem quickly emerged as a media celebrity and a lead-

ing publicist for feminism. She has argued that sexism and racism are re-

lated caste systems and that heterosexism is a form of patriarchy, and she

has sought unity with African Americans and lesbians.

One of the ironies of Steinem’s ascendancy as a feminist leader in-

volves her physical attractiveness. At a time when women were demand-

ing to be judged on their abilities, intelligence, and skills and not on their

physical appearance, Steinem’s physical appeal provided reassurance to

some women that feminists can be attractive and enjoy the company of

men, in addition to having power. This combination of power and sexu-

ality threatened some men while giving her access to other male decision-

makers. A late arrival to the feminist movement, Steinem became an in-

stant celebrity within it and in the media.

Born in Toledo, Ohio, Gloria Steinem graduated from Smith College

in 1956 after spending her junior year in Geneva, Switzerland, and a sum-

mer at Oxford University in England. She went to India on a fellowship

for almost two years beginning in 1957. While there, she traveled through-

out the country, wrote travel pamphlets and other material, and studied

Mahatma Gandhi’s strategies of nonviolence. Gandhi’s teachings influ-

enced the rest of Steinem’s life, including her later involvement with Do-

lores Huerta’s, Cesar Chavez’s, and the United Farm Workers’ organiza-

tional campaigns. She returned to the United States in 1958 and began

looking for work in New York but was unsuccessful.

Steinem moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1959 to direct a

nonprofit educational foundation that encouraged American youth to at-

tend International Communist Youth Festivals in an attempt to counter

Communist influence. Steinem did not know that the foundation was

partially funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, but in the 1970s the

connection was the basis for an attack on Steinem by radical feminists.

640 Steinem, Gloria Marie

In the early 1960s, Steinem was a

freelance journalist, writing for Esquire,

Glamour, Vogue, Ladies’ Home Journal,

New York Times Magazine, and other pub-

lications. In 1963, she went underground

and applied for a job as a Playboy bunny.

She held the job long enough to write an

article about the experience. Published in

Show magazine, the article made her an

instant celebrity. In it she exposed the

poor working conditions and low wages

paid women at the Playboy Club. In 1968,

she was a founding editor of New York

magazine and became one of the coun-

try’s first female political commentators.

During the late 1960s, Steinem also began

her career as a political activist when she

became involved with Democratic Party

politics and worked with Dolores Huerta

and Cesar Chavez for United Farm Workers and their table grape boycott.

While covering a 1969 abortion hearing organized by Redstockings

leader Kathie Sarachild in New York, Steinem became aware of her femi-

nist beliefs, describing the event as “the great blinding light bulb” that led

to her identifying herself as a feminist. Speaking on behalf of feminism

became her next goal, but she was terrified of public speaking and re-

cruited a partner. In 1970, Steinem and African American activist Dorothy

Pitman Hughes began addressing groups on the topics of women’s rights

and civil rights. Later, one of the people with whom Steinem spoke and

traveled was Florynce Kennedy. During a cab ride, the two women were

discussing abortion, when the driver said: “Honey, if men could get preg-

nant, abortion would be a sacrament,” a quote that Steinem and Kennedy

often used and one that became part of the movement’s most effective

consciousness-raising tools.

In 1971, Steinem joined several veteran feminists to found the Na-

tional Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC), one of her earlier cooperative ef-

forts with some of the established leaders of the feminist movement.

Steinem’s response to Congresswoman Bella Abzug, another NWPC found-

ing member, provides an indication of Steinem’s development as a feminist

at the time. She found Abzug’s style too loud and too brash, until Steinem

came to realize that she was using a patriarchal definition of appropriate be-

havior for women. As Steinem’s feminism matured, she admired Abzug for

her courage and strength and worked on her subsequent campaigns.

Steinem, Gloria Marie 641

Gloria Steinem,

founder of Ms.

magazine, whose

name became syn-

onymous with the

“second wave” of

feminism (Courtesy:

Ms. magazine)

In 1971, Steinem and Brenda Feigen founded the Women’s Action

Alliance to help women overcome the barriers they encountered at the lo-

cal level, including marital abuse and desertion, sexist textbooks, and lack

of job opportunities. Enthusiasm for the alliance led to the idea of a

newsletter, which Feigen argued should be in a magazine format. Ms.

magazine evolved from these discussions.

A sample issue of Ms. appeared in the 1971 year-end edition of New

Yo rk magazine, and a preview issue was published in the spring of 1972,

selling out in eight days despite the skepticism of publishing industry ex-

perts. The first regular issue appeared in mid-1972. Steinem brought to-

gether a talented staff, including publisher Pat Carbine. Carbine and

Steinem attempted to avoid creating a hierarchy in the magazine’s orga-

nization, but Steinem was and remained the publication’s dominant fig-

ure, even though she was regularly absent lecturing and raising money to

keep it going. Steinem planned to shepherd Ms. for a few years and then

move to other projects, but its ongoing financial instability kept Steinem

at its head for fifteen years.

With high hopes for the magazine’s success, Steinem created the Ms.

Foundation for Women in 1972 to be the beneficiary of its profits.

Steinem believed the foundation would fill a philanthropic gap because at

the time there were no foundations that gave money to women as a group

or a category. The magazine did not enjoy the financial success that

Steinem had hoped for, but the foundation developed its own resources

and by the late 1990s had an annual budget of $6.2 million and an en-

dowment fund of $10 million.

After the Equal Rights Amendment passed Congress in 1972 and

went to the states for ratification, Steinem joined other feminists in trav-

eling the country to develop support for it. Also that year, at the Demo-

cratic National Convention, the NWPC chose Steinem for its spokes-

woman. Steinem gained further attention at the convention when she and

Fannie Lou Hamer nominated Frances “Sissy” Farenthold for vice presi-

dent of the United States, but Farenthold did not succeed.

Through her work and Ms. magazine, Steinem developed a loyal

constituency of feminists, but others criticized her. Feminist author Betty

Friedan, who had helped launch the modern feminist movement with the

publication of The Feminine Mystique in 1963, viewed Steinem as a com-

petitor for the leadership of the movement and worked to undermine and

discredit her. The two women disagreed on the issues, particularly the

movement’s responsibility to lesbians. Friedan regarded lesbians as a men-

ace, but Steinem believed that lesbians were an important part of the fem-

inist movement. In 1975, the Redstockings, a radical feminist group, ac-

cused Steinem of having a ten-year-long association with the Central

642 Steinem, Gloria Marie

Intelligence Agency, referring to her foundation work in the late 1950s.

The Redstockings questioned her loyalty to feminism and implied that she

might be an informant. The group also questioned the motives of the

Women’s Action Alliance and asserted that Ms. magazine hurt the femi-

nist movement because it was inadequately radical. The allegations did

not have merit, but they did reveal some of the fragmentation within the

feminist movement.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed Steinem to the National

Commission on the Observation of the International Women’s Year, 1975.

The next year, she was a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at the Smithsonian In-

stitution. In 1979, Steinem was a founder of Voters for Choice, an inde-

pendent political committee organized to support prochoice congres-

sional candidates.

Steinem continued her work with Ms. magazine, writing for it and

raising money to keep it in business. The readership was stable, but costs

had escalated, and the advertising revenue had been a constant disap-

pointment. After she discovered that she had breast cancer in 1986,

Steinem felt the need to have fewer responsibilities and wanted the free-

dom to write. When the opportunity to sell Ms. appeared in 1987, she

took it and sold the magazine to an Australian communications con-

glomerate. Steinem remained as a consultant for five years.

Steinem has written Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983);

Marilyn, a biography of Marilyn Monroe (1986); Revolution from Within:

A Book of Self-Esteem (1992); and Moving beyond Words (1994).

See also Abzug, Bella Savitzky; Equal Rights Amendment; The Feminine

Mystique; Feminist Movement; Friedan, Betty Naomi Goldstein; Huerta,

Dolores; Kennedy, Florynce Rae; Ms. Foundation for Women; Ms. Magazine;

National Women’s Political Caucus; Redstockings

References H. W. Wilson, ed., Current Biography Yearbook, 1988 (1988); Heil-

brun, The Education of a Woman (1996).

Stewart, Maria W. (1803–1879)

The first woman in the United States to stand on a lecture platform and

raise a political issue before an audience of women and men, African

American Maria Stewart spoke against a plan to repatriate black Ameri-

cans to Africa during her lecture on 21 September 1832 in Boston, Mas-

sachusetts. An abolitionist and women’s rights champion, Stewart urged

blacks to demand their human rights from their oppressors and called on

women to develop their intellects and participate in the community. Ac-

cording to Stewart, a religious conversion experience had made her a

“warrior” obedient to God’s will, leading her to protest tyranny, victim-

ization, injustice, and political and economic injustice. In four years, from

Stewart, Maria W. 643

1831 to 1835, she wrote the first political manifesto by a black woman,

wrote a collection of religious meditations, delivered four public lectures,

and compiled her work into a volume of collected works.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Stewart was a household servant

during her young adolescence and a domestic servant from the time she

was fifteen until she married in 1826. Widowed in 1829, she underwent a

religious experience that led to her brief public life. She moved to New

York in 1834 and taught school there as well as in Baltimore and the Dis-

trict of Columbia. After the Civil War, Stewart was matron of the Freed-

men’s Hospital.

See also Abolitionist Movement, Women in the; Public Speaking

References Richardson, ed., Maria W. Stewart, America’s First Black Woman

Political Writer: Essays and Speeches (1987).

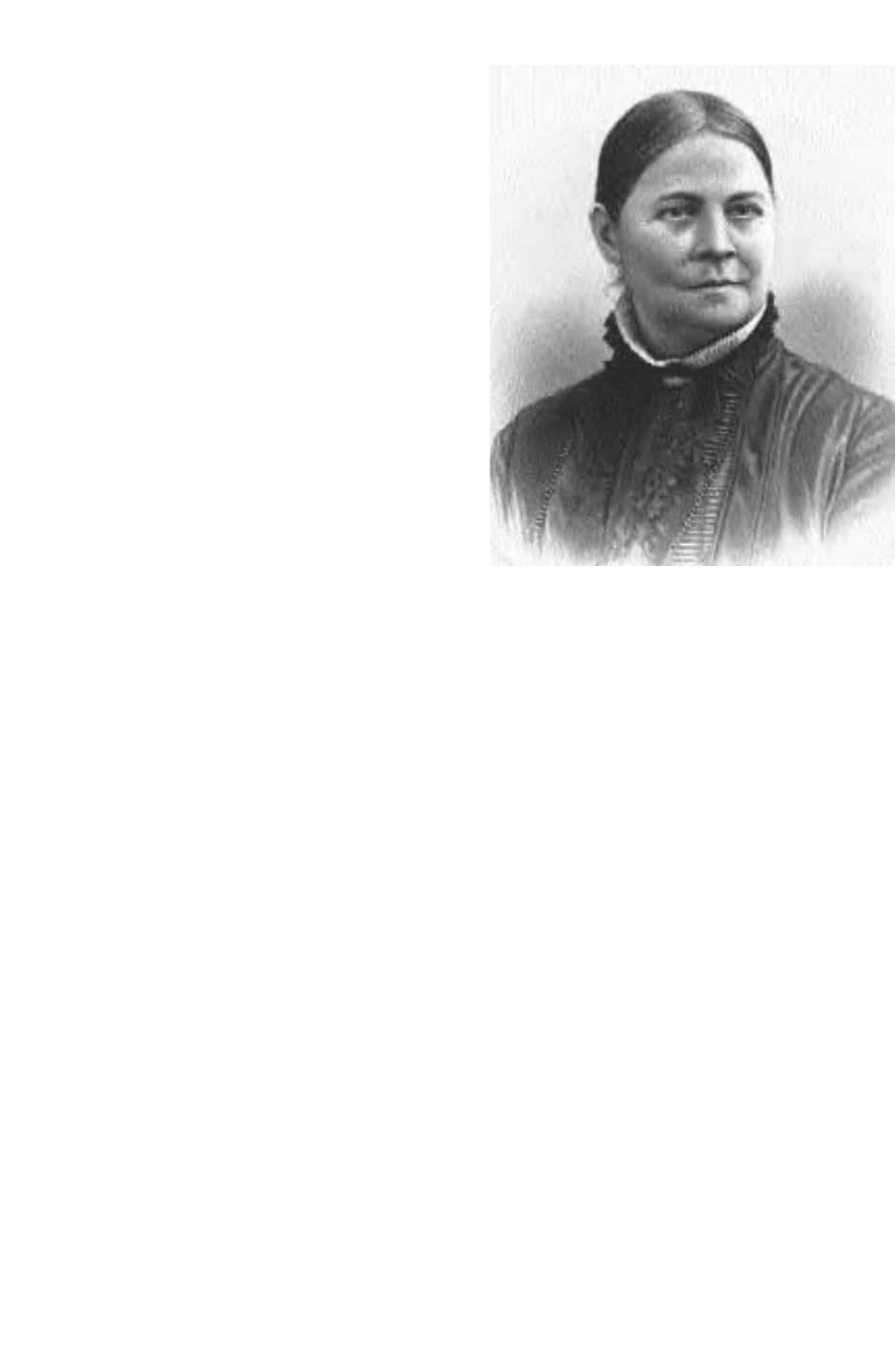

Stone, Lucy (1818–1893)

Abolitionist lecturer and suffrage leader Lucy Stone and her husband

Henry Blackwell founded the American Woman Suffrage Association

(AWSA) in 1869. Stone gained notoriety for retaining her family name af-

ter her marriage, and other women who did the same became known as

Lucy Stoners.

Born near Brookfield, Massachusetts, Stone yearned for a formal ed-

ucation, for which her father refused her financial assistance. She began

teaching when she was sixteen years old, saving her earnings to attend

academies and seminaries that would prepare her for a college education.

When she entered Oberlin College in 1843, Stone believed that women

should vote and run for office, study the professions, and become public

speakers for reform causes, philosophies that Oberlin College did not

share. Chosen to prepare a graduation essay during her senior year, Stone

objected to the college’s traditions that permitted male students to read

their essays in public but prohibited women from reading theirs, instead

having professors present the women’s essays. Stone refused to have a pro-

fessor read her work, and it was not presented. She received her bachelor

of arts degree from Oberlin College in 1847, the same year she made her

first public speech on women’s rights.

After graduating, Stone became an agent for the American Anti-Slav-

ery Society and an independent women’s rights lecturer. An accomplished

orator, she attracted audiences as large as 3,000 people. Her public

speeches also created controversy because it was considered scandalous

for a woman to speak before audiences of men and women. The hostility

she evoked appeared when people tore down posters announcing her

speeches, burned pepper in the audience while she spoke, and threw

644 Stone, Lucy

prayer books and other items at her. At

other times, angry mobs prevented her

from speaking.

In 1850, Stone and other suffragists

called a national convention on women’s

rights in Worcester, Massachusetts, which

more than 1,000 people attended. In her

speeches on women’s rights, Stone dis-

carded the notion of “separate spheres”

and called for women to define their

spheres of work and influence. With equal

educational opportunities, she argued,

women would find their appropriate

sphere. Stone criticized the church, which

she believed was committed to the contin-

ued subjugation of women, and her out-

spokenness contributed to her being ex-

pelled from the Congregational Church.

Stone also attacked the concept of women losing their personhood in

marriage under the laws of coverture. In her lectures, she condemned

marriage as little better than chattel slavery for women, but she reserved

her greatest criticism for the economic relationship between a woman and

a man that marriage laws defined. With other activists of the time, she

worked for revisions in married women’s property laws that would give

women power over their property and earnings. Stone also believed that

women should be able to control the number and spacing of their chil-

dren through male restraint and that women should be able to refuse sex

with their husbands. In cases of drunkenness or loveless marriages, she

believed that divorce needed to be an option.

Despite her strong views against marriage, Stone married Henry

Blackwell in 1855, after years of persistence on Blackwell’s part. An aboli-

tionist and feminist, Blackwell shared Stone’s views, including her refusal

to take his name. During their wedding ceremony, they publicly declared

their distaste for the unjust marriage laws of the period, including their

objections to laws giving a husband control of his wife’s person, of their

children, and of her property and earnings and the loss of the wife’s legal

existence.

Stone continued to lecture until the birth of their daughter in 1857,

when she found it difficult to maintain her career and raise a child. After

the Civil War, she returned to suffrage work, especially focusing on ef-

forts to remove the word male from the proposed Fourteenth Amend-

ment, but she was unsuccessful. In 1867, Stone and Blackwell went to

Stone, Lucy 645

Lucy Stone, well-

known abolitionist

and suffragist,

founded the

American Woman

Suffrage Association

in 1869 (Library of

Congress)

Kansas to campaign for the state’s proposed amendments to grant

African Americans and women suffrage rights. Upon her return to New

York, she learned that Susan B. Anthony, who was also campaigning in

Kansas, had used Stone’s name in connection with lectures that Anthony

and George Train were giving. Stone and many other abolitionists

viewed Train, a racist Democrat, with disdain and saw him as a threat to

their work because although he supported woman suffrage, he opposed

suffrage for African Americans. When both amendments failed, Stone

held Train accountable for the losses. She also publicly distanced herself

from Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had also aligned herself

with Train.

The schism in the woman suffrage movement was formalized in

1869 when Anthony and Stanton formed the National Woman Suffrage

Association (NWSA), and in response Stone organized the AWSA. The

next year, Stone and Blackwell began publishing The Woman’s Journal,

which existed for forty-seven years. In the mid-1870s, with the suffrage

movement needing new energy, Stone organized local suffrage clubs,

which supported both federal and state constitutional amendments.

In 1887, Stone presented a resolution to the AWSA convention to ne-

gotiate a merger with the NWSA, and in 1890, the first National American

Woman Suffrage Association meeting was held. Stone, too ill to attend,

was elected chair of the executive committee. She died three years later.

See also American Woman Suffrage Association; Anthony, Susan Brownell;

Coverture; Fourteenth Amendment; Married Women’s Property Acts; National

American Woman Suffrage Association; National Woman Suffrage Association;

Separate Spheres; Stanton, Elizabeth Cady; Suffrage

References Kerr, Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality (1992); Matthews,

Women’s Struggle for Equality (1997); Ravitch, ed., The American Reader

(1990); Spender, Feminist Theorists (1983).

Stop ERA

Founded by Phyllis Schlafly in 1972, Stop ERA worked to defeat state and

federal Equal Rights Amendments. During the campaign for ratification

of the federal Equal Rights Amendment, members effectively lobbied state

legislators to vote against ratification. Through its strong grassroots net-

work, members used the media in innovative ways; for example, they gave

legislators loaves of bread with notes saying: “I was bred to be a lady and

like it that way.” Following defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1982,

Stop ERA disbanded.

See also Eagle Forum; Equal Rights Amendment; Schlafly, Phyllis Stewart

646 Stop ERA

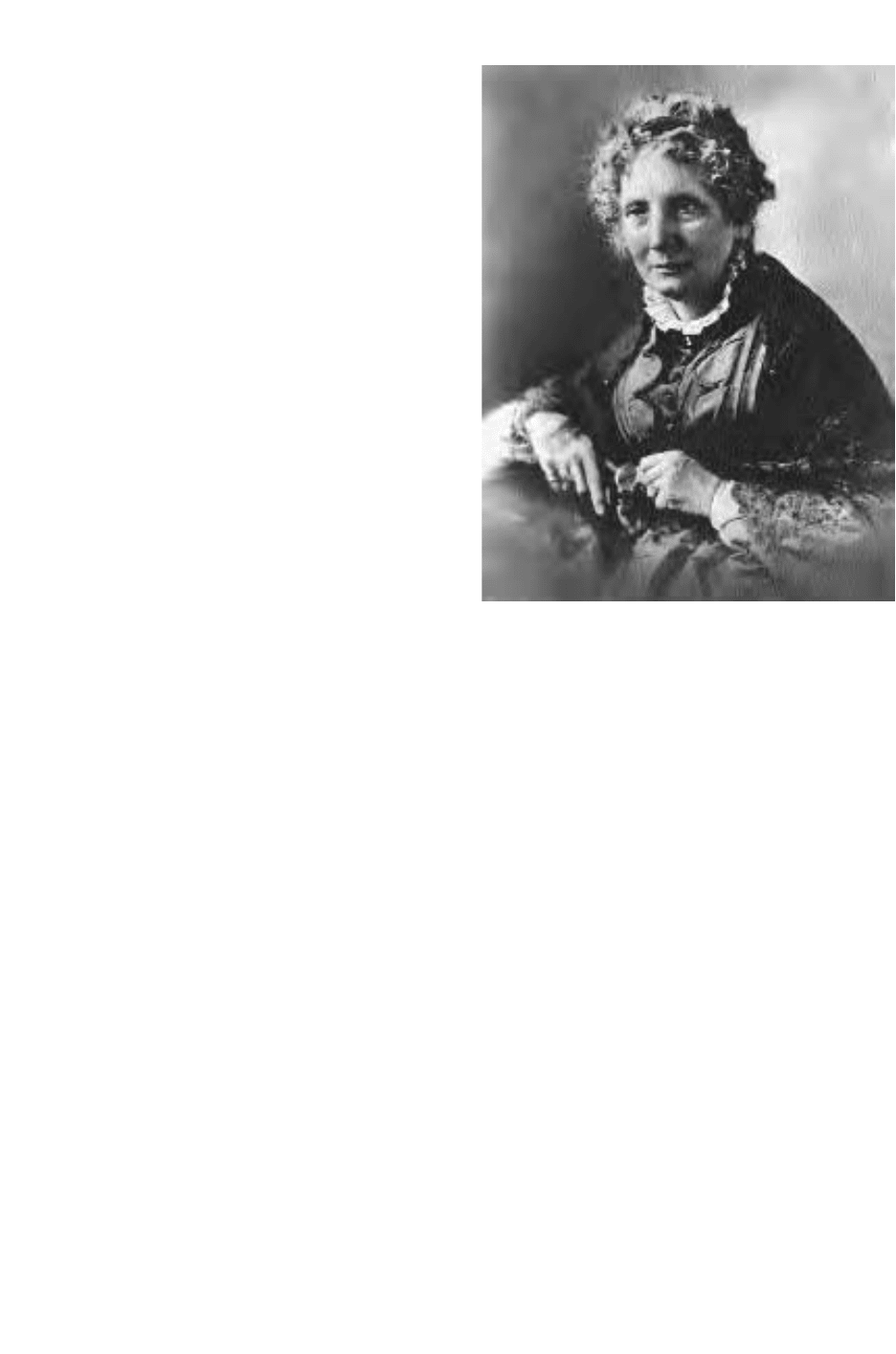

Stowe, Harriet Elizabeth Beecher

(1811–1896)

Considered a profoundly political writer,

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the 1852

novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which deepened

antislavery sentiment in the North. Serial-

ized in a magazine beginning in June 1851

and continuing through March 1852, Un-

cle Tom’s Cabin exposed tens of thousands

of Americans to the human horror of

slavery. The characters Stowe created res-

onated with readers who appreciated a

story and who did not read the political

tracts and other antislavery material of

the time.

Passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act

prompted Beecher to write a series of

sketches about slavery, and they evolved

into Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By writing a polit-

ical and dramatic piece, Beecher moved beyond the kind of novel women

generally wrote in the mid–nineteenth century. When she met President

Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, he reportedly said, “So this is the

woman who started the big war.”

Born in Litchfield, Connecticut, Stowe was the daughter of Presby-

terian minister Lyman Beecher and the sister of Congregational clergy-

man Henry Ward Beecher and educator Catharine Beecher. She attended

Connecticut Female Seminary in 1824.

See also Abolitionist Movement, Women in the

References Scott, Woman against Slavery: The Story of Harriet Beecher Stowe

(1978).

Suffrage

U.S. women gained the vote in 1920 with the passage of the Nineteenth

Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The woman suffrage movement

had its origins at the 1848 Seneca Falls, New York, convention for women’s

rights. For the next seventy-two years, women organized, petitioned,

marched, and passed state referenda measures in their efforts to become

fully enfranchised voters.

For a brief time, New Jersey did not have restrictions against women

voting after 1776. If a person owned at least 50 pounds worth of property,

had been a resident for at least one year, and was over twenty-one years of

Suffrage 647

Harriet Beecher

Stowe garnered

sympathy for the

abolitionist cause

with her novel Uncle

Tom’s Cabin, which

was far more political

than women’s litera-

ture of the day

(Library of Congress)

age, the person was qualified to vote, whether male or female. Because the

U.S. Constitution stipulated that anyone who could vote for the most nu-

merous branch of state government could also vote in federal elections, it

meant that women could also vote for members of Congress and the pres-

ident. In 1806, New Jersey changed its constitution, and no woman in the

United States could vote because New Jersey women had been the only

female voters in the country. The New Jersey experience was an anomaly

and did not precipitate the suffrage movement.

The suffrage movement emerged from the abolitionist movement, in

which women found their actions limited and their efforts constrained.

Frustrated with the social and political restraints placed upon them, some

women leaders in the abolitionist movement came to believe that unless

they had full citizenship rights, their ability to effectively work for the end

of slavery would remain marginal.

The 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London highlighted the

limits of women’s effectiveness for two women in particular. Lucretia

Mott, a U.S. delegate to the convention, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who

had recently married and had accompanied her husband to the conven-

tion, found themselves and other women banished from the meeting floor

and relegated to a balcony. While in their forced seclusion, Mott and Stan-

ton resolved to hold a convention on women’s rights, but it took eight

years for them to act on their decision. The meeting finally took place in

648 Suffrage

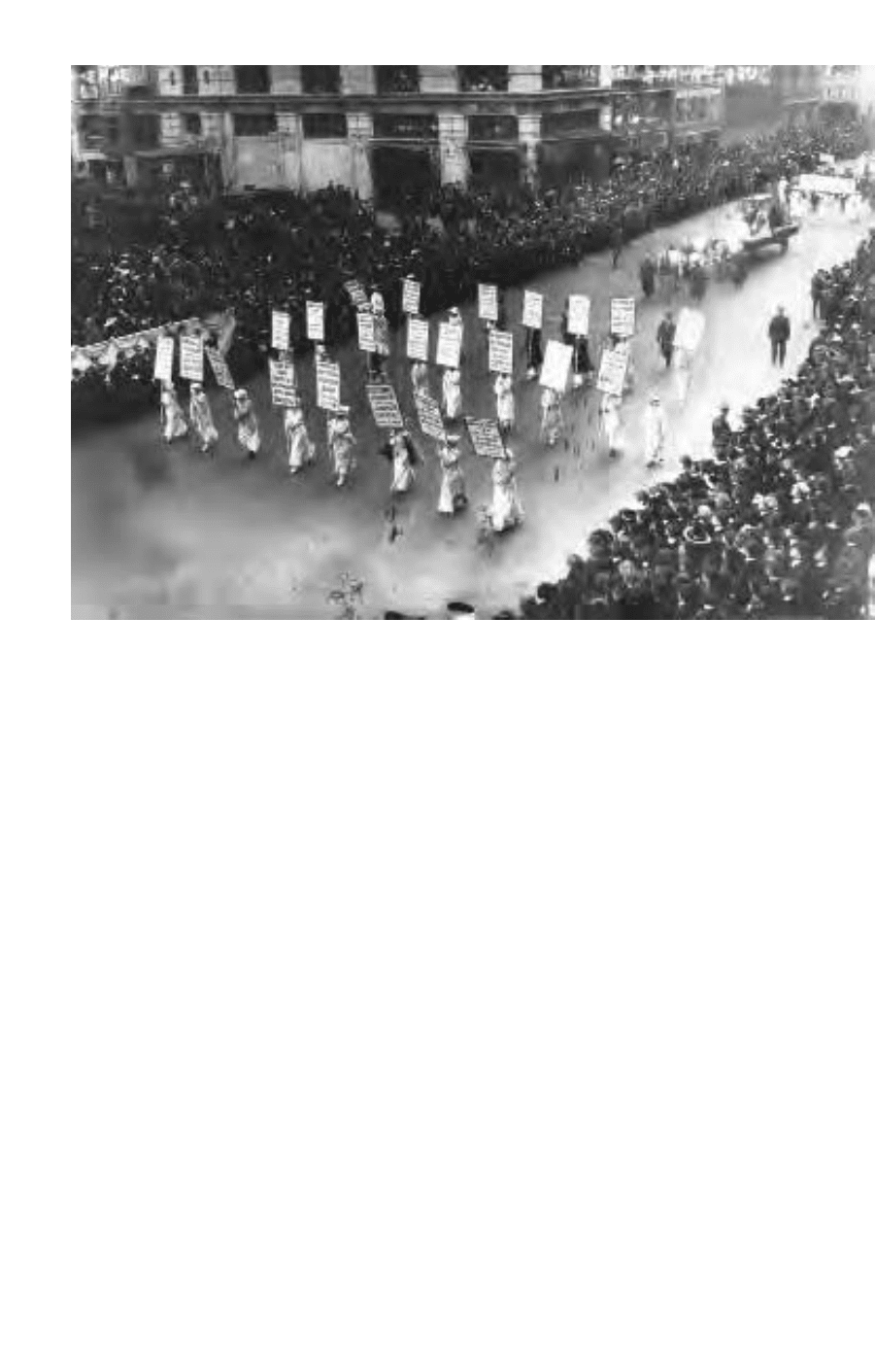

Suffrage parades like

this one in New York

City advanced the

progress of the vote

for women, 1913

(Library of Congress)