Roll Forming Handbook / Edited by George T. Halmos

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.12 Marking

Permanent product marking is frequently required. Stationaryorflying dies can be used for permanent

marking.

In thick materials, the marks are most often stamped in. The stamp either remains unchanged (trade

mark, supplier’sname, “Made in USA,”etc.) or is variable for serial numbers or other identifications.

The marking is most frequently embossed in thin materials (see also Section 4.9).

Rotarydie or ink stamping,ink jet, adhesive bonded tag,laser,and other marking methods are also

used by the manufacturers of nonpermanent or permanent marking.

4.13 Swedging (OffSetting)

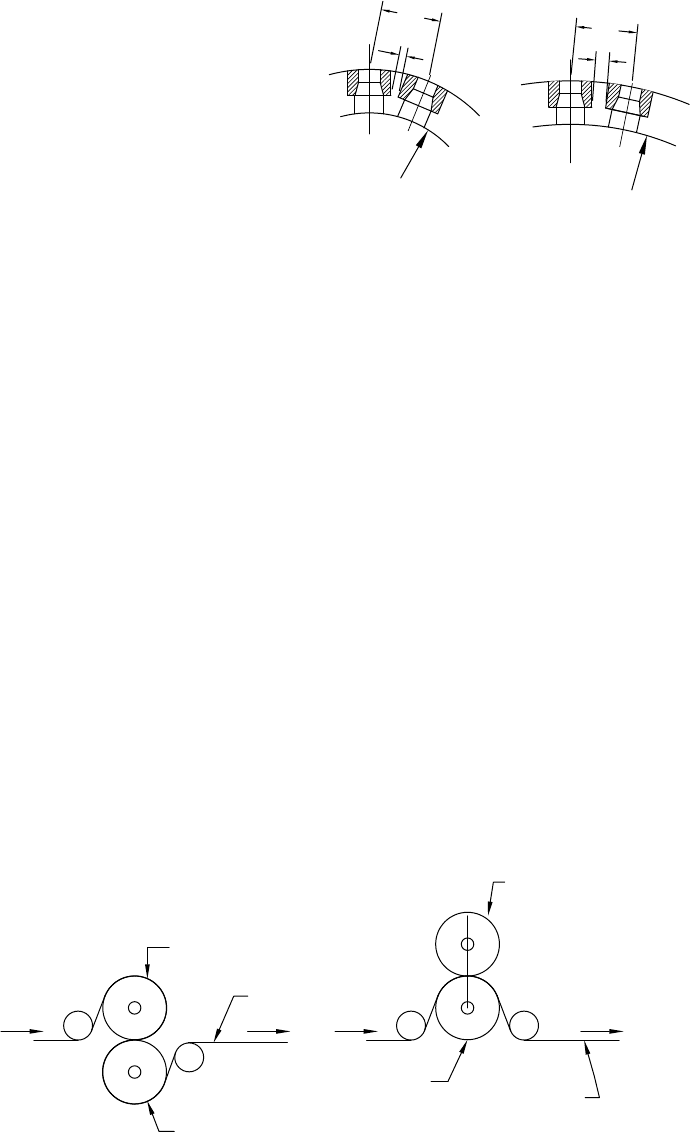

In the swedging operation, the shape of the cross-section is changed (Figure 4.108). Swedging is applied

when product has to be overlapped with the same surfaces remaining at the same height. Swedging is

usually carried out in the cutoffdie and requires considerably higher tonnage than simply shearing the

same product.

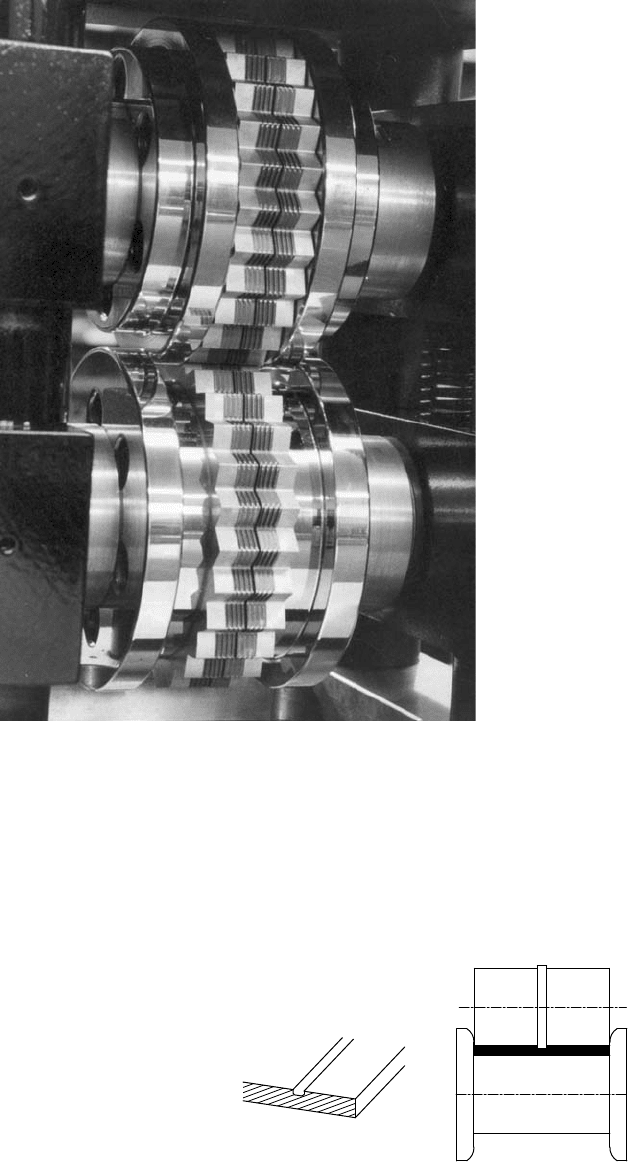

4.14 RotaryDies

4.14.1 RotaryDies and Stands

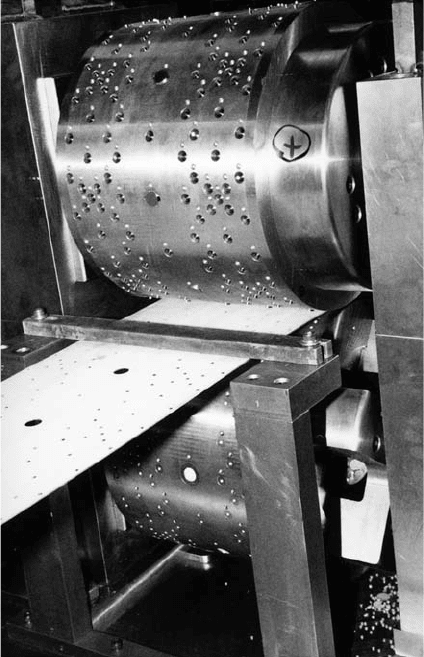

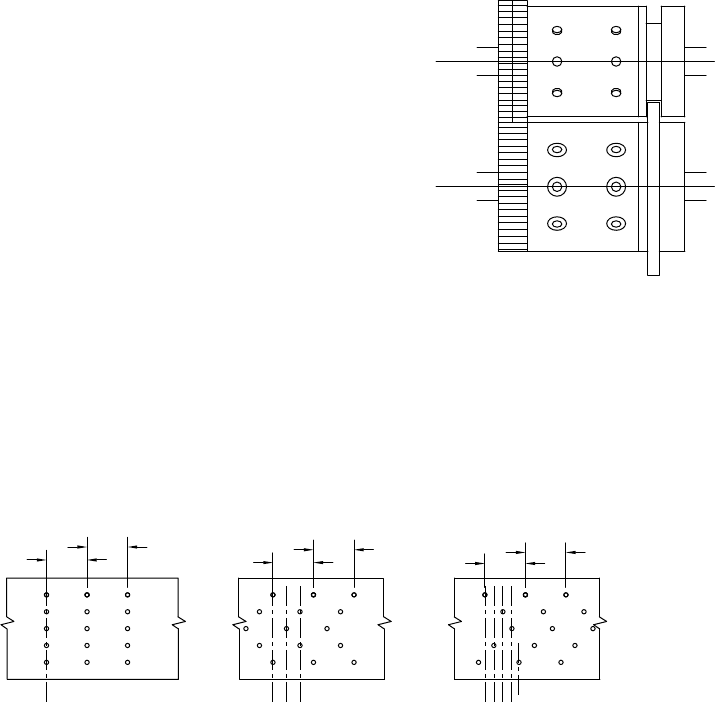

The roll forming industryhas developed a

uniquerotatingdie concept, utilizingthe

continuous travelofthe strip propelled by the

roll forming mill. In the rotarydie, the top and

bottom rollsare geared together (Figure4.109).

One roll holds the punches, the other one holds

the dies. The rotarydie is usually driven by the

strip through friction or by punch engagement.

If aslug is generated, then the bottom rotary

die usually has acavity, with one or both ends

open for slug disposal.

Rota ry dies canbeusedfor punching,

notching,par tial punching,dimpling,piercing,

embossing,limited flanging,louvering, miter-

ing,slitting,coining,marking, serrating,knurl

ing,shearing to length, curving,and other

operations.

B

A

C

R

1

FE

D

AB

R

0

CD EF

t

r

t

o

t

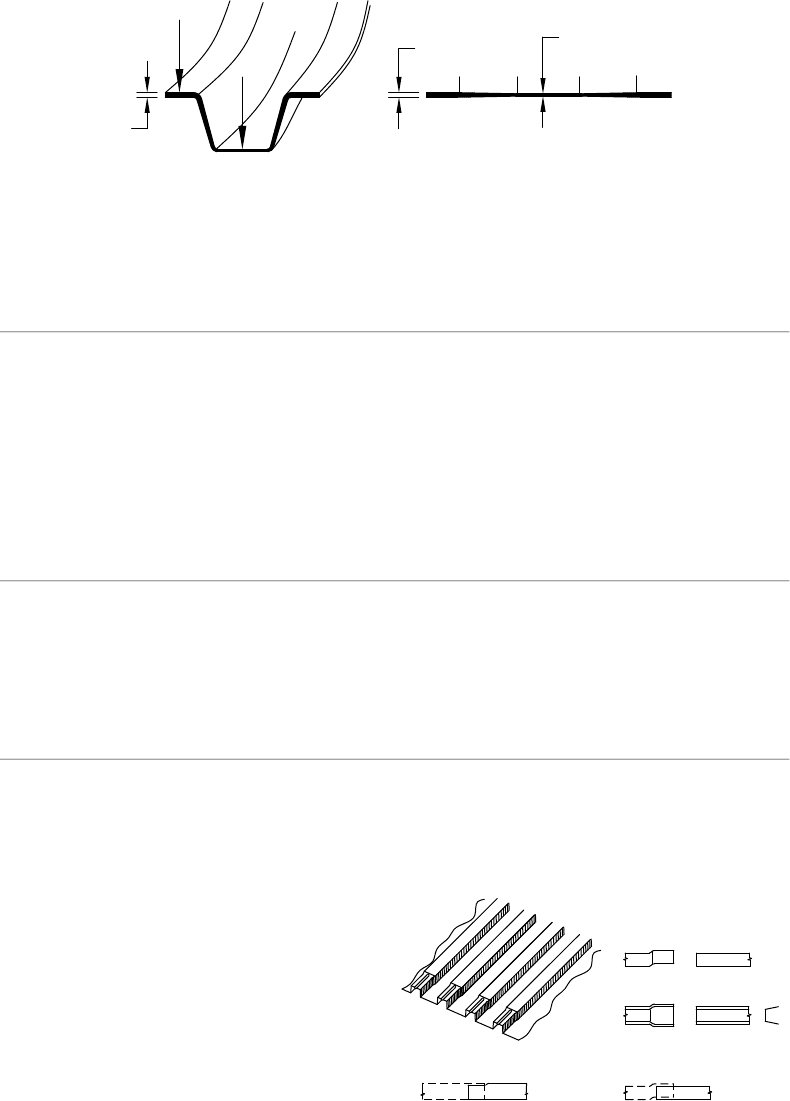

FIGURE 4.107 Curving can be achieved by reducing the thickness of the outer fibers.

(a) same plane (b) not in the same plane

FIGURE 4.108 Cutends are swaged when overlapping

product surfaces must remain in the same plane.

Roll Forming Handbook4 -46

The advantages of the rotary dies are:

*

Less expensivethan press and dies.

*

No feeder (or die accelerator) is required.

*

Usually no driveisrequired.

*

Speed is not limited (can run at 1000 ft/min [300 m/min]).

*

Provide uniform repeated pattern.

The disadvantages are:

*

Less flexible than the conventional press method.

*

The pattern is uniform, but it is difficult to makeadjustments.

*

Material thickness for punching is usually limited to 0.070 in. (1.8 mm). However,with special

arrangements, thicker materials (e.g., 0.200 in. [5 mm]), can be processed.

*

Burr may be heavier than those generated by conventional punching,but frequently the burr is

flattened by the rolls used for forming.

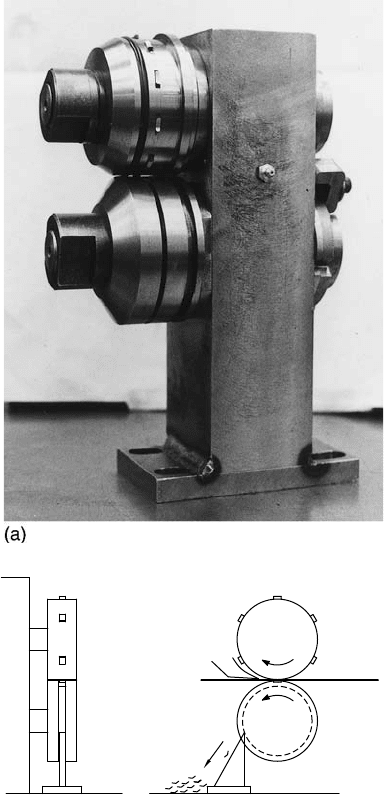

In most cases, rotary punches, notching tools, and dies require precise locating; hence, backlash gears are

used on both rolls. However,ifaseries of less critical holes are required in the longitudinal direction, such

as nail holes for sidings, then the rotary operation can be simplified. The upper die has the punches and

the lower roll has only aslot (Figure4.110a). The punches cut through the material and push the slugs into

FIGURE 4.109 Rotarypunching unit. (Courtesy of Delta Engineering Inc.)

Secondary Operations in the Roll Forming Line 4 -47

the slot. Close to the bottom, afinger reaches

into the slot, prying the slugs out from the slot

(Figure4.110b). This small, relatively low-cost

arrangement does not require backlash gearing

between the top and bottom rolls. The burr will be

larger after punching,but the rolls in the mill will

flatten the burr down.

Rotaryoperations are frequently similar to the

press operations. The forces generated by the

operations are larger then the ones required for

forming.Therefore, rotaryoperations usually

require larger shaft diameters, larger capacity

bearings, better top shaft adjustment, sturdier

stands, and very accurate shoulder alignment.

If the distanceofthe holes, notches, emboss-

ment, and louvers from the strip edge is critical,

then thestrip ca nbetrappedinthe rolls

(Figure4.111). In other cases, such as decorative

embossment, the rollsare wider than the strip and

the use of strip entryguides are usually sufficient.

During therotar yoperations,the tool is

engaged in the material. As aresult, thereisno

material slippage during engagement and no

compensation for strip speed differential between

therotar yand roll formingoperation.The

simplest solution to avoid problems is not to

drive the rotary tools.

The material must be engaged into several

passes to havesufficient friction to pull through

the rotary dies. It is feasible to open up the gap

between the rotary dies, engage the strip into the

mill and then close the gap again. This is atime-

consuming process and the lead end of each coil

would be wasted. Therefore, in the case of small

forces (thin material, single hole, or emboss-

ment), the operator side of one shaft can havea

square end to facilitate ahand crank (Figure

4.112). The strip is moved through and punched

(embossed) betweenthe rollsbyhanduntil

sufficient length is generated to be caught and

pulled by the forming rolls.

Manual threading is neither practical nor feasible when the torque requirement is too high(thick,

high-strength material, multiple operations at the same time, etc.). In these cases, amotorized, slow die

rotation is used with an overriding clutch. The strip passes through the rotary dies slowly,and once the

forming rolls grab it, probably at the third or fifth pass, it is pulled throughbythe mill at aspeed higher

than the speed of the rotary tool roll.Then, the overriding clutch lets the strip turn the rotary unit. An

alternative solution is to weld the coil ends together.

If the rotary operation was not considered at the time of designing the line, and the mill does not have

sufficient horsepowermotor to pull the material through the rotary dies, then aseparate rotary punch

drive mayberequired. Because it is very difficult to synchronize the speed of the mill and the rotary

operation, aloop with aloop control is recommended between the rotary unit and the mill.

FIGURE 4.110 Rotarypunching unit utilizing punches

in the upper roll and aslot in the bottom roll (a); slugs are

removed with afinger reaching into the slot (b).

slugs

(b)

stripper

Roll Forming Handbook4 -48

4.14.2 RotaryPunching

In rotary punching,the conventional up and

down movement of the press ram is replaced by

rotating tools and dies. One of the rolls, usually

the upper one, contains the punches and the

other one the dies. The tworolls are rotating with

thesamesurface speed as thestrip travels

betweenthem. Thepunch enters into the

material at an angle (Figure 4.113), punches it

through,and then gradually retracts from the

hole as the rolls rotate and the strip moves. The

angle between the punch and the strip changes

constantly during this process.

It is well known that geared teeth profiles have

an involute curve shape. This shape enables

smooth entryand exit of the teeth.

The rotating punches and the dies cannot have

involute shape; therefore, there is always adegree

of interference and deviation from ideal con-

ditions. The smaller the rolldiameter is in

relation to the material thickness, the bigger the

interference and the problems created by this

interference.

To minimize the problems created by this

deviation from the ideal conditions, the ratio of

the rolldiameter to the material thickness must

be keptrelativelylarge.Practical experience

indicatesthatthe roll diameter should be

at least 250 to 270 or even 300 times the mild

steel thickness ð D ¼ 250 to 270 t). In the case

of slotted bottom die, the ratio can be smaller

ð D ¼ 170 to 180 t).

The exact roll diameter is afunction of the distancebetween the holes in the finished product. For

example, if the material thickness is 0.024 in. (0.61 mm), then the approximate diameter of the rolls should

be about 250 £ 0.024 ¼ 6in. (152.4 mm). If the hole distanceinthe finished product is 3in. (76.2 mm),

inboard

stand

outboard

stand

rotary

die

strip

guides

punch

guide

gap

strip

rotary

punch

FIGURE 4.111 Strip trapped between rolls during rotary

punching.

forhand

crank

FIGURE 4.112 The entryend of thin strips can be hand-

cranked through the rotarypunches.

slug

α

α

FIGURE 4.113 The angle between the punch and the strip continuously changes during the punching process.

Secondary Operations in the Roll Forming Line 4 -49

then the perimeter of the rolls should be 18 in. (457.2 mm) for six punches and dies. The approximate roll

diameter,therefore, will be 18 (

p

¼ 5.73 in. (145.5 mm) for six punches and dies, or 6.68 in. (169.8 mm)

for seven punches and dies around the perimeter.

Figure4.114 shows that if the incoming strip is wrapped around the die roll, then the punch enters into

the material somewhat later than in the case of astraight entry. This approach provides slightly better

accuracy than in the tangential approach. With reasonably good accuracy,the rolldiameter plus two times

the material thickness can be used to calculate the driving perimeter (Figure 4.115). Because of the angular

motion, even this approach requires some correction. Rotarydie manufacturers are using their own

equation to calculate the proper rolldiameters.

In everycase, however,itisimportant to keep the punches as shortaspossible. No extra length

should be allowedfor regrinding.When regrinding is required, ashim, equivalent to the amount of

grinding,has to be placed underneath each punch. For example, if the punch length is reduced

by 0.003 in. (0.076 mm), then a0.003-in. (0.076-mm) shim should be placed underneath of each

punch.

b

a

β

α

curvedstrip

contact points

straight strip

FIGURE 4.114 The punch enters at asmaller angle ð b Þ when the strip is wrapped aroundthe die roll (b), compared

with the usual tangential entry(aand a ).

D t

D r

t

FIGURE 4.115 The actual driving diameter is close to D

t

:

Roll Forming Handbook4 -50

To prevent the slugs from falling onto the strip,

the upper roll contains the punches and the

bottom roll contains the dies. The slugs fall into a

cavityinthe bottom die. It is advisable that the

cavityistapered to ensure that the slugs will fall

out unaided from the rotating roll. The strength

of the bottom roll wall should be sufficient to

withstand the punching pressureaswell as to

provide enoughdistancebetween adjacent dies

(Figure4.116). If the distancebetween dies is too

small, then increasing the roll diameter some-

times helps.

In special cases, instead of falling through the

die opening,the slugs are knocked out with a

special device.Similarly,the punch can be moved out of the home position with acam at the last moment

and then pulled back (stripped) to avoid the problems related to the angular entr yand exit of rigid

punches.

Because the punch normally exits from the hole at an angle, the stripping is morecritical. The most

common stripper is asmaller rollclose to the roll containing the punches. An alternative is to havefingers

reaching as close as possible to the contact point between the rolls. Proper tension on the strip and a

well-placedstripper will provide asmooth, punched strip surface.

Rotarypunching will create moreburrs than ordinarypunching; however, in most cases, the burr is

flattened back by the pressureofthe rollsinthe roll forming mill. If burr cannot be eliminated in this way

and has to faceupwards, then different threading of the material can place the burr on the upper surface

(Figure4.117).

If punches are constantly engaged, then there is little chancefor the strip to slip between the rolls.

However,ifthe punches are far apart(e.g., only one or twopunches are in the rotary die), then slippage

may occur.Achange in material thickness (from coil to coil, or within one coil) can also create slippage if

the gap is set by screws. Slippage problem in these cases can be minimized by:

1. Using urethane, rubber,orother elastic material rings with an outside diameter slightly larger

that the roll diameter of the rotary die.

2. Applying hydraulic or spring pressure instead of fixed position screw pressure.

3. Threading the strip around both rolls(Figure 4.117b) instead of contacting them at one line.

The arrangement on the left side (Figure 4.117a) is used if the burr must face upward.

m

Rsmall

Rbig

a

n

a

FIGURE 4.116 The die roll wall must havesufficient

strength. If “n”istoo weak, increasing the roll diameter

sometimes helps (“m” is sufficient).

die roll

(a) (b)

burr up

punch roll

punch roll

die roll

burr down

FIGURE 4.117 Threading the strip as shown in (a) reverses the burr direction; threading as shown in (b) reduces

slippage.

Secondary Operations in the Roll Forming Line 4 -51

Accurate alignment of the punches and the dies is

very critical in rotary dies because of the rotary

motion.Tokeep thepunchesand thedies

angularly aligned, no-backlash gears are attached

to the rotarydie rolls (instead of just keyed to the

shaft). In the direction of the shaft axis, the

punches and the dies can be aligned with the

male die reaching into agroove(Figure 4.118).

The gap between the male and the female die

should be only 0.001 to 0.002 in. (0.025 to

0.050 mm), and they should not touch each

other.The gap is strictly for setup purposes;

therefore, theshoulderalignment andshaft

straightness are critical.

The biggest forces on the rotary die and

the biggest resistanceagainst pulling are during

punching engagement. To minimize the shock,

the sudden increase in pressure and the resistance to rotation, it is recommended to stagger the holes in

the longitudinal direction wherever possible. An 80% reduction in the sudden increase of resistance could

be achieved with afive-punch arrangement shown in Figure4.119.A66% reduction was achieved by

staggering dimpling punches and dies shown in Figure4.120.

Owing to the bending forces on the punches during entering and exiting,rotary punching is not

recommended for small-diameter holes or narrowslots going across the strip.However,narrow slots in

the longitudinal direction might be considered (Figure4.121).

The surfaces of the punches are either flat (Figure4.122a) or havearadius concentric to the roll

(Figure4.122b). Some punches are ground to differentshapes to minimize pressure or to help slug disposal

(Figure4.122c). However,increasing the punch length may create other problems as mentioned before.

Rotarypunches usually haveasurprisingly long life. Occasionally,punches maybreak, usually as a

result of misalignment. Therefore, aquick-punch-replacement design is essential. Removing the rotary

unit, taking it apart, and putting it back together again would be aslowprocess. Punch removal is also

required when shims are placed underneath the punches for regrinding.Proper fastening must prevent

the slipping of punches and dies out of the rolls.

To ensurethat the punches enter in the dies perpendicularly,itisrecommended to tie the top shaft

adjusting screws on the operator side and the driveside together.This will ensure parallel movements of

the shafts, rolls, and punches.

As with other punching operations, lubrication can be acritical factor for tool life. The lubricant used

for rollforming is not necessarily the best lubricant for punching.

FIGURE 4.118 Punches and dies are aligned by no-

blacklash gears and guide rolls.

betternot recommended

(a) (b) (c)

recommended

5holes /"a" distance

a

a

a

a

a

a

FIGURE 4.119 Staggered punches reduce sudden loads by 80%.

Roll Forming Handbook4 -52

Owing to the hig h-speed operation, averylarge number of slugs is generated. Mechanized removal of

slugs (chute or belt) is recommended instead of frequent stopping of the line to removethe slugs manually.

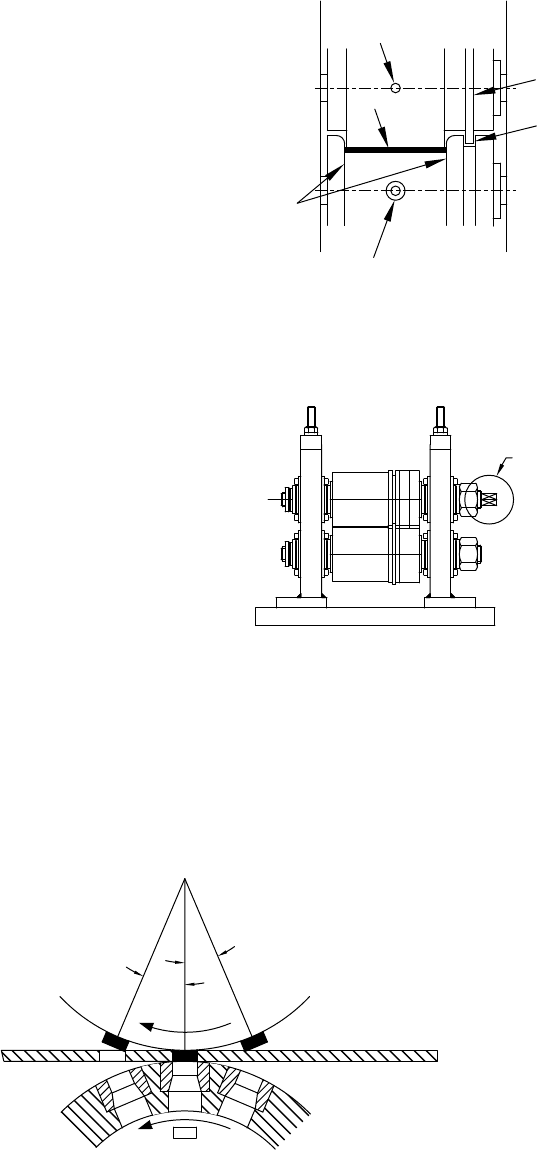

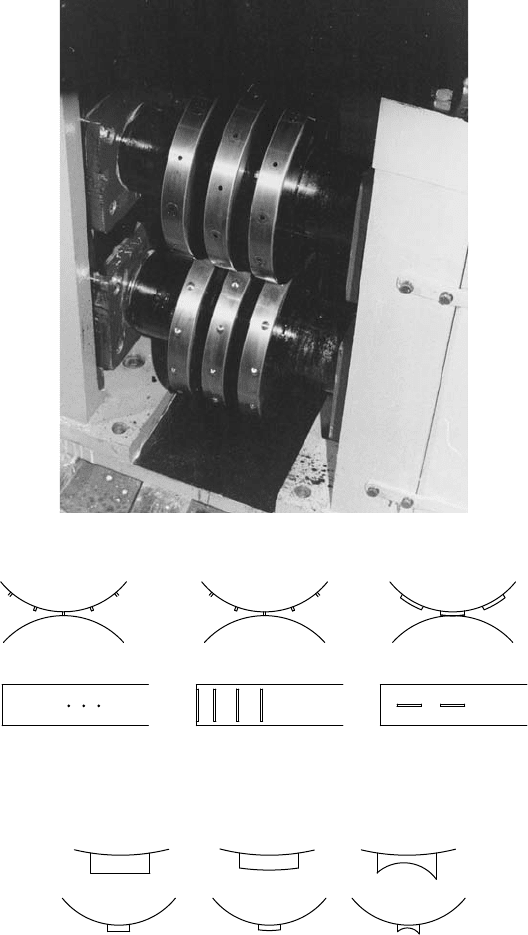

4.14.3 Embossing

Rotaryembossing punches and dies are similar to the ones used in the conventional embossing

operations. The maximum depth of embossment is afunction of factors described in Section 4.9.1.

FIGURE 4.120 Staggered dimpling punches and dies reduce the load by 66%.

not recommendednot recommended better

FIGURE 4.121 Small, slender punches can brake easily.

(a) (c)(b)

FIGURE 4.122 Punch surfaces can be different to reduce load or burr.

Secondary Operations in the Roll Forming Line 4 -53

Because of the relatively large forces created by embossing,the rotary punches and dies are installed into a

separate, usually undriven stand (Figure4.123).

Usually,the shape and radii of the dies will eliminate the entering and exiting problems frequently

experiencedduring rotary punching.However,inconventional dies, the material is kept flat by the die,

while in rotary embossing,the contact is only at one line. This maycreate bigger distortion in the strip

because the close, relatively deep embossments generate internal stresses in the material. Internal stresses

may result in substantial bow. However,the longitudinal bow, occasionally accompanied with twist, can

usually be disregarded because, in most cases, the product will be straightened by the stripper located at

the exit side of the embossing rolls, by the bend lines, or by astraightener at the end of the line.

Toomanydeep embossments will reduce the length of the embossed section of the product. If the

embossment is in the wide center partofaflat section with formed edges, then the products maytwist or

distorttosuch adegreethat flattener cannot correct the problem.

If longitudinal embossments are at an angle to the direction of forming,then the rotary action may

generate unwanted forces, thus pushing the strip sideways (Figure4.124a). To minimize the problem and

to reduce the camber and twist created by unevenstretching of the material to one side, symmetrically

opposite embossment is recommended (Figure 4.124b).

Shallowembossments are used for identifica-

tion (stamping) or for decorative purposes.

Decorative panels areembossedbetween special

engraved rolls, whichgeneratelarge forces andare

usuallyinstalled on aseparatestand withtheir own

drive, with aloopbeforeand oneafter theunit.

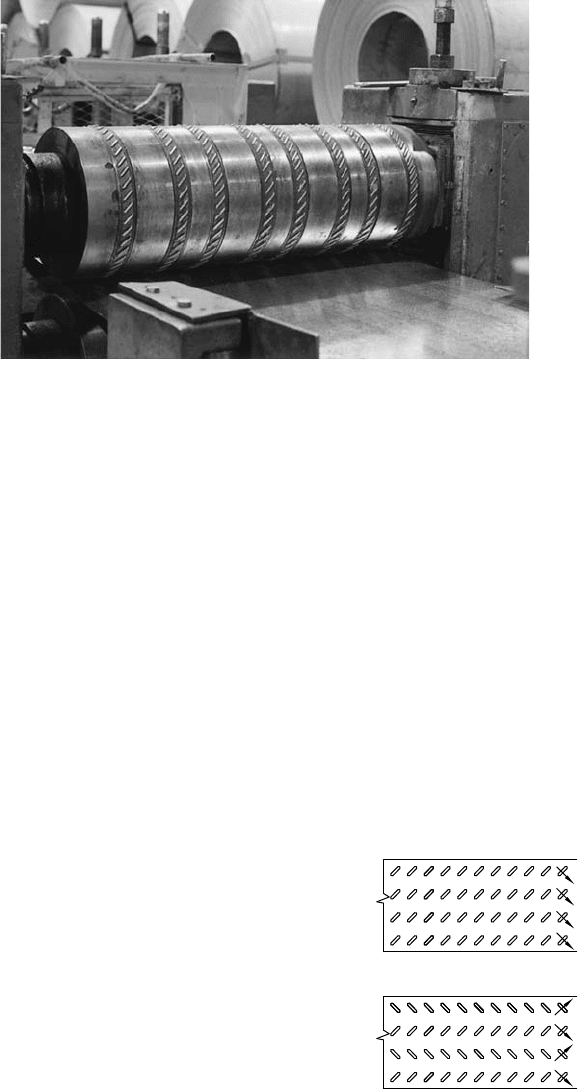

4.14.4 Louvering and Lancing

During louvering,lancing,and similar oper-

ations (Figure4.43 and Figure 4.44 ), an opening

is cut, adjacent to the embossed and or bent

material, without creating slugs. Rotarylouver-

ing usually requires aconsiderably higher ratio of

roll diameter to die penetration than rotary

punching.Rotarylouvering is successfully used

FIGURE 4.123 Rotaryembosser for composite decks.

recommended (balanced)

not recommended(a)

(b)

FIGURE 4.124 Modified embossing pattern (b) can

eliminate the side pressure caused by embossments in one

angular direction (a).

Roll Forming Handbook4 -54

in manyapplications. Forexample, in the case of heat exchangers, 0.002 to 0.003-in. (0.05 to 0.075-mm)

thick aluminum strips are rotary louvered at over 1000 ft/min (300 m/min) speed (Figure4.125).

4.14.5 Grooving, Coining, and Knurling

In the process of grooving (Figure4.126)and

coining (Figure 4.127), the material thickness is

locally reduced. In most cases, the roller opposite

to the grooving and coining rolls havesmooth

surface.

In the case of knurling,both rollshavepatterns.

Given the proximity of peaks and the geometryof

the pattern, this operation is acombination of

embossing and coining.Ifthe knurling pattern is

not symmetrical, then one edge of the strip may

become shorter than the other one. This can result

in excessive camber,waviness, twist, and bow.

FIGURE 4.125 Rotarylouvered heat exchanger strip.(Courtesy of Livernois Engineering Company, Heat Exchange

Division.)

FIGURE 4.126 Rotarygrooving.

Secondary Operations in the Roll Forming Line 4 -55