Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

12.6 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Communications

Communications worked quite well in this project, which was pioneering a new type of accessible

mass transit. The TAG won the European Community Helios award for best transport achievements

in 1989. The cities of Strasbourg and Bordeaux followed the example of Grenoble, and the Grenoble

accessible tram model was then chosen abroad by the cities of Turin, Italy, and Brussels, Belgium.

Education

The accessible tram has increased the presence of persons with disabilities in the city, enabling

greater access to both education and employment.

Signage and Signals

Recognizing accessibility signs does not seem to be a problem for users. Easily identifiable direc-

tions are indicated at both ends of each tram. The button to be pushed for the retractable doorstep

opening is highly visible and accessible. Voice announcements are made at each station on the tram-

way and bus lines, and tactile signs are installed for users who are blind.

12.4 THE GRANDE GALÉRIE IN THE MUSÉUM D’HISTORIE

NATURELLE, PARIS, 1989–1994

The building that houses the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle was built in 1889. It is located in the

Jardin des Plantes, between the Austerlitz Station and the Latin Quarter. Closed to the public in 1965,

the Galérie engaged in information gathering and research, but remained rather secretive.

Refurbishment Project

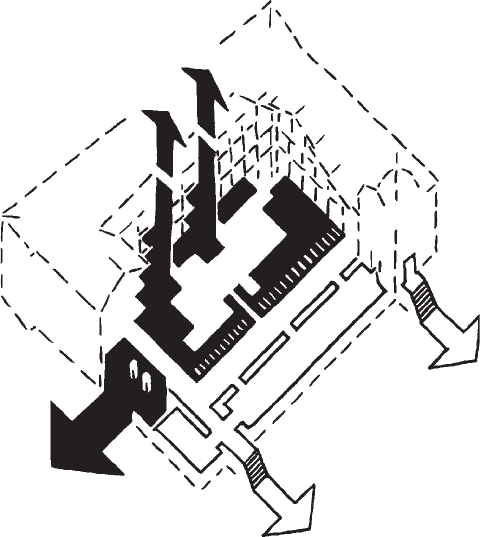

An architectural competition organized in 1989 was won by Paul Chemetov and Borja Huidobro.

Of all the building’s functions (i.e., research and collection storage), only the exhibition function

survived. But the architects had a double goal—to create a contemporary museum, to be visited by

the general public, and to restore a nineteenth-century building. The public entrance was originally

located on the facade that overlooks the garden, up an inaccessible monumental staircase (Figs. 12.4

and 12.5).

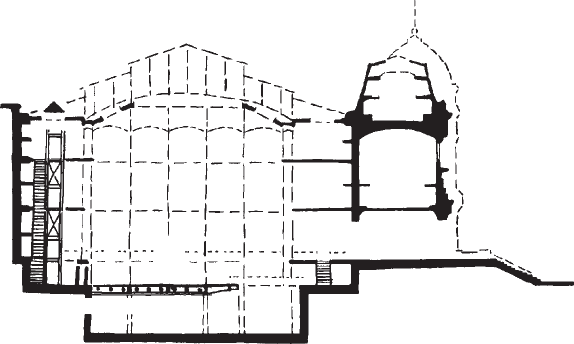

The architects decided to move the entrance to the side of the building, at street level, thus allow-

ing easy access to the surrounding area. Panoramic glass elevators made the three gallery levels

surrounding the central space accessible. As the space was not large enough to comply with the

plan as envisaged, the basement was converted into exhibition space. This project actually involved

redesigning a building, which was done by identifying the old and the new parts and by integrating

accessibility into the new parts from the start.

Language

As defined by the consultants, Amplitude, the goal was to achieve complete accessibility. This

was to “include reduced mobility and sensitivity in the definition of the criteria used to establish

the conditions in which visitors might experience disability for themselves” (Amplitude, 1990). In

addition, the public was “to be able to move through the gallery’s entire exhibition space without

having to be segregated through any specific route,” because “comfort and social interaction have to

THE EVOLUTION OF DESIGN FOR ALL IN PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND TRANSPORTATION IN FRANCE 12.7

No entrance at grade

Old entrance stairs

FIGURE 12.4 Grande Galérie du Muséum (Chemetov and Huidobro, archi-

tects): new accessible entrance after renovation. The old entrance was inaccessible

because of staircases. (Drawing by the author.)

Long description: The axonometric drawing shows the old entrance with two

inaccessible monumental staircases on the facade that overlooks the garden, an

element of a nineteenth-century building preserved, and a new entrance created by

the architects on the side of the building at street level that is easily accessible.

be sought” (Amplitude, 1990). Designed in the 1990s, this project illustrates how the vocabulary has

evolved significantly as a consequence of the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie de Paris experience

(Grosbois and Araneda, 1982).

Legal Requirements

The Grande Galérie was opened in 1994, the very year when the regulations became stricter. The

project proved that regulations were only a minimum requirement that could be broadened by the

architect, Paul Chemetov, who argued that “cities today attribute a dominant role to information and

reception” and “locating the entrance on the side, i.e., the accessible facade, was thus a key option.”

Architecture critics perceive the concept of the free visitor flow as part of the concept of accessibil-

ity: “Nothing has changed but everything is different. A direct entrance at street level leads to the

museum, since now the street and the side aisle are connected and are on the same…level” (Lamarre,

1994). This case shows that the concept of the free visitor flow went beyond the literal application

of legal requirements.

12.8 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Advocacy

As part of the refurbishment project of the Grande Galérie, consulting accessibility for disabled

people was commissioned by a design office. In this case, there was no advisory committee of

associations.

Planning

The Laboratoire de Sociologie de l’Éducation had been developing a research program with the

Québec University CREST (Évolution 93, 1993) since 1989, whose purpose was to study the Jardin

des Plantes and the general public attending exhibitions in the museum. This program contained

three parts: a sociodemographic survey, a survey of knowledge and competency, and a survey of

visitors’ needs and behaviors. Accessibility studies were subsequently integrated into the specifica-

tions to take the variety of the public’s motor and sensory abilities into account. Several teams of

contributors shared the work based on their professional skills: the team of architects worked on

refurbishing the building, filmmaker René Allio designed visual and sound spaces, and the A.D. Sign

Agency designed the exhibition spaces.

Technical Traditions

The A.D. Sign Agency was created by architects involved in the museum project, as an independent

organization in charge of the museum spaces and the development of displays. The beautiful nine-

teenth-century industrial display cabinets were kept, but adapted to contemporary museum graphics

requirements. The 3-meter- (10-foot-) high display cabinets provided all visitors, including children

and wheelchair users, with excellent visual access.

New entrance at grade level

Old entrance stairs

Lift slazed car

FIGURE 12.5 Grande Galérie du Muséum (Chemetov and Huidobro, architects): another view of the

new accessible entrance. After renovation, the new entrance and the three gallery levels are accessible.

(Drawing by the author.)

Long description: The section drawing of the building shows the old entrance inaccessible with monu-

mental staircases and the new entrance accessible at the opposite part of the building at street level.

This project redesigns the building, identifying the old and the new parts, and integrates accessibility

into the new part from the street.

THE EVOLUTION OF DESIGN FOR ALL IN PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND TRANSPORTATION IN FRANCE 12.9

This case shows that it is possible to combine traditions with technical evolution to preserve a

building’s identity. René Allio’s (1994) stage-set approach combines sound and light, and he says

that animals “will prompt visitors to complete the images they see with their feelings and sensitivity,

so strong is the animals’ evocative power.” As the animals are set on the floor, persons with visual

impairments can make tactile explorations. According to d’Eggis and Girault (1997), “the associa-

tion of visual, sound and tactile possibilities provided by the scenography explains a great deal of

the Grande Galérie’s success.”

Accessibility Follow-Through

One important factor was the education of museum staff regarding visitors’ varying needs. Guided

visits for the deaf are accompanied by deaf lecturers and actresses, who adapt their tours to the needs

of their audiences. Workshops have been created to complete training for the blind, so that they can

sense the exhibits better by touching them, e.g., forms, textures, animal furs, skeletons, and dimen-

sions. This accessibility follow-up policy is essential to “attract an audience that does not always fit

in cultural places” (d’Eggis and Girault, 1997).

Communications

The magazine Musées et Collections Publiques de France published an issue entitled “How to

Receive People with Disabilities,” showing that communications about all these new accessible

places are developing (“Recevoir les handicapés,” 1997). In addition, various associations were

strongly involved in the development of a communications network.

12.5 CONCLUSIONS

The French examples of design for all reveal issues of compromise based on cultural, technical, and

economic factors. This illustrates how accessibility may be developed by each country via social

and technical considerations. This is a universal goal that deserves everyone’s respect, and one that

respects everyone’s right to be part of social life through the use of buildings and transportation. It

must not be confused with a policy of compromise to be defined according to each culture.

It now appears clear that law is only a tool, but political determination and democratic referenda

set the various objectives and pursue their implementation. This reflects the evolution of the users’

demands and the evolution of technical solutions. In Grenoble, this entailed the demand for acces-

sibility and the definition of new transportation equipment, meaning an automatic metro and new,

comfortable, safe, and elegant tramways. In public buildings, it entailed accessibility for all users,

after their diverse abilities were defined. Humankind has to be considered as the focus, with technol-

ogy playing the supporting role. Professional roles prove to be symbolic rather technical obstacles.

The notion of the diversity of individuals is obvious, and the recommendation to designers is clear:

Public spaces need to be designed for the public and all the diversity therein.

12.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allio, R., “Sons et lumières, vision de cinéaste,” Revue d’architecture créée 259, 1994.

Amplitude, Accueil des publics handicapés, Paris: Direction des musées de France, 1990.

Comité de lutte des handicapés, “Abrogation complète et immédiate,” Habitat et vie sociale, no. 22:36–37,

1978.

Document transport de l’Agglomération de Grenoble (TAG), 1987.

12.10 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

d’Eggis, S., and Y. Girault, “Politique d’accueil des personnes handicapées visuelles et audititives,” Musées et

Collections publiques de France, no. 214:41–42, 1997.

Évolution 93, Lettre d’information de la cellule de préfiguration de la Grande Galérie, 11, Paris: Muséum

National d’Histoire Naturelle du Jardin des Plantes, 1993.

Grosbois, L. P., Handicap et construction, 8th ed., Paris: Le Moniteur, 2008.

——— and A. Araneda, Critères d’accessibilités aux présentations, Paris: Musée National des Sciences et de

l’Industrie, 1982.

———, I. Joseph, and P. Sautet, Habiter une ville accessible, Paris: Ministère de l’Equipement et du Logement,

1992.

Musées et Collections publiques de France, “Recevoir les handicapés,” Paris, 1997.

Norman, D. A., “Grandeur et misère de la technologie,” La recherche, 285:22–25, 1996.

Vitruvius, Les dix livres d’architecture, Paris: Les Libraires Associés, translated in 1965.

12.7 RESOURCES

Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, www.mnhn.fr

Transport de l’Agglomération de Grenoble (TAG), www.semitag.com

CHAPTER 13

MANIFESTATIONS OF

UNIVERSAL DESIGN

IN GERMANY

Ingrid Krauss

13.1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of universal design (UD) is increasingly gaining a foothold in Germany, in architecture,

planning, and design, as well as in politics and business, where it is seen as a possible answer to the

challenges of demographic change. After a brief outline of the economic and social relevance of the

concept, this chapter describes various initiatives and developments in this area.

13.2 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RELEVANCE OF UNIVERSAL

DESIGN IN GERMANY

Like most other industrialized countries, Germany is faced with the consequences of an increasingly

aging and simultaneously declining population. Whereas the proportion of those aged over 60 was

only 5 percent in 1900, today this figure has risen to 25 percent and will reach almost 40 percent

by 2050. Demographic change can have severe consequences on society and the economy. It affects

planning and construction of buildings and infrastructures, product design, information and com-

munication systems, and the design of services as well.

The 1970s already saw approaches similar to UD in the German-speaking region, such as “social

design” for which the Institute for Social Design (ISD), founded in Vienna in 1975, among others,

remains an advocate. The ISD’s mission is the “improvement of people’s living conditions through

concrete changes in all areas of planning and design of products, objects, living and work spaces.” At

the heart of its efforts is “the person, who is entitled to expect that his/her wishes, needs and potential

are taken into consideration.” The ISD is predominantly involved in two areas: barrier-free design

and the design of workplaces and equipment. Since 1975, numerous projects have been realized in

these areas. The concept of social design was being implemented in Germany at the same time and

was also represented in the 1970s at the International Design Center Berlin.

Due to the increasing aging of industrial societies, the social approach is accompanied by an eco-

nomic one. Meanwhile, knowing the needs of older consumers and taking them into consideration in

the development and design of products and services have become an important issue. In view of the

size and purchasing power of this target group, it promises competitive advantages and market suc-

cess. In addition, studies and tests, such as those carried out by the London-based Research Institute

13.1

13.2 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

for Consumer Affairs, prove that products that have been developed with an eye to the needs of the

older generation actually have cross-generational appeal. This is so because of their greater user-

friendliness and better handling, and thus, they are appreciated by all age groups. One important

criterion is, however, that such products should not look as if they have been made for “old people,”

i.e., they should not have a discriminating effect (Meyer-Hentschel and Meyer-Hentschel, 2004).

However, not only has demographic change resulted in an increased need for products and envi-

ronments that are accessible and user-friendly. Also because of the increasing aging of employees

and longer working lives, there is a great need for workplaces that meet UD criteria.

13.3 UNIVERSAL DESIGN VERSUS DESIGN FOR ALL (DfA)

Parallel to UD—both in terms of theoretical engagement and in practice—the concept of design for

all (DfA) is also being applied in Germany and other European countries. Common to both concepts

are the orientation toward people’s diverse needs, wishes, and abilities and the aim of making the

environment accessible to all. The underlying premise of both concepts is that all people, irrespec-

tive of their individual abilities, age, gender, or cultural background, should be enabled to participate

equally in society.

The central goals of DfA state that products and services must be designed in such a way that they

1. Are demonstrably suitable for most of the potential users without any modifications

2. Are easily adaptable to different users (e.g., by incorporating adaptable or customizable user

interfaces)

3. Are capable of being accessed by specialized user interaction devices (assistive technologies)

4. Involve potential users in all phases of their development

As with the explicitly stated seven Principles of Universal Design, the first three requirements relate

to the result of the design process, while the fourth describes the process itself. This is where, along

with the different historical and cultural contexts out of which they emerged, the main difference

between the two concepts lies. While with UD the focus is on the end product, DfA is process-oriented

and is less concerned with drawing up principles, standards, guidelines, and checklists. While check-

lists can be “ticked off” during the development and design process, DfA relies on the involvement of

potential users, where this means not only the end users, but all those involved in the design, develop-

ment, production, and marketing processes (Kercher, 2008).

While in terms of theoretical debate both UD and DfA represent known and much discussed

concepts, the concept of accessibility (Barrierefreiheit) remains the approach most commonly used

in Germany. This is most certainly due to the fact that the term barrier-free (barrierefrei) has already

been used in the German-speaking region since the 1960s, and it is firmly embedded in legislation

and standards, e.g., in the Disabled Persons’ Equality Act (Behindertengleichstellungsgesetz, or

BGG). The demand for accessibility is primarily implemented in the area of public planning and

construction, as well as in the design of products and Internet services.

It has been codified, e.g., in national standards developed by DIN (Deutsches Institut für

Normung), the German Institute for Standardization, such as DIN 18024 (DIN, 1996, 1998) which

formulates requirements for the barrier-free construction of public thoroughfares and buildings, or

DIN 18025 (DIN, 1992a, b) which outlines the requirements for constructing barrier-free housing.

Furthermore, the standards committees have published various guidelines and recommendations

for barrier-free design in specialized reports, e.g., DIN Technical Report 124 (DIN, 2002) or DIN

Technical Report 131 (DIN, 2003). This is identical to the international ISO/IEC Guide 71 and the

European CEN/CENELEC Guide 6, issued by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN)

and the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC).

In contrast to design that is oriented toward the concepts of UD and DfA, barrier-free design does

not always mean design without stigmatization. Often function-oriented solutions are created which,

because of a lack of alternative options, or because of their unappealing design, are felt to have a

MANIFESTATIONS OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN GERMANY 13.3

stigmatizing effect. Here, one can cite the example of the chair lift, with which the wheelchair user

is heaved onto an ICE (Inter City Express) train, or the ramp, which is installed at a side or rear door,

hidden well away from the main entrance.

Avoiding stigmatization and bearing human diversity in mind during the design process are the

main aims of UD and DfA. It is not primarily a question of designing special solutions for older

people or those with impairments which are attractive, such as walking aids, telephones with large

keypads, grab bars, etc. The key issue is to reduce the complexity of everyday items, to design clearly

structured user interfaces that can be operated intuitively, to produce packaging that anybody can

open, to write operating instructions that everybody can understand, and to build housing suitable for

all ages and abilities. In short, it is a question of designing in a people-friendly way.

13.4 POLITICAL INITIATIVES AND PROMOTIONAL MEASURES

Politicians such as the German Federal Minister of Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth,

and the German Federal Minister of Economics and Technology, both recognized the potential of con-

cepts such as UD and DfA, and they are encouraging the advancement of these design approaches

through long-term promotional measures. As such, the Federal Ministry of Family Affairs, Senior

Citizens, Women and Youth and the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology jointly launched

the “Age: An Economic Factor” (Wirtschaftsfaktor Alter) initiative in 2008. This initiative aims both

at increasing older people’s quality of life and at strengthening economic growth and creating jobs.

As Federal Minister Ursula von der Leyen stated, “If we promote products and services today, which

people of all ages use and like, Germany with its rapidly aging society has the great opportunity of

setting standards and becoming a world market leader for generation-friendly products, before foreign

competitors fill these gaps in the marketplace.”

And indeed, the gaps in the market are still considerable, and the needs of older people are not

being adequately taken into account by trade and industry. Although persons over age 60 already

represent an important target group—both financially and in terms of numbers—and are responsible

for a large share of consumer spending, they are still seen as a marginal social group with special

needs. Products on the market aimed at older people are often stigmatizing. Additionally, people with

limited capabilities are excluded from using certain areas, goods, and services.

Politicians have recognized the subsequent need for action, such that concepts like UD and DfA

are now seen as worthy of promotion. On one hand, they can help to increase the social participation

of older people and those with disabilities. On the other hand, companies that consistently apply these

concepts when developing their products and services can realize lasting competitive advantages.

13.5 INFORMATION AND NETWORKING: THE UNIVERSAL DESIGN

COMPETENCE NETWORK

Within the scope of the “Age: An Economic Factor” initiative, the Universal Design Competence

Network is currently being built up at the International Design Center Berlin (IDZ). Bringing

together information, ideas, skills, and knowledge on the subject of UD; promoting the exchange

of experience; and helping to disseminate UD as a human-centered design approach are the central

aims of the network. It is directed at designers, as well as at research institutions and companies.

In order to present this theme to a broad public, a traveling exhibition with accompanying publica-

tion was created in 2008. The exhibition “Universal Design: Designing Our Future” was opened at the

IDZ in November 2008 and remained there until January 2009. By the end of 2010 it will have been

shown across Germany in various places and contexts, e.g., at the leading consumer and trade fairs, as

well as at Chambers of Commerce and Industry, Chambers of Skilled Crafts, and in a number of other

design centers. The interactive exhibition displays over 50 everyday products, the user-friendliness

of which enhances the quality of life for both old and young; visitors are encouraged to try out the

13.4 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

products on display. The exhibition makes it clear that design must come to grips not only with new

technological developments, but also with social change. The accompanying publication picks up on

the theme, with contributions by eight leading authors from the areas of design, culture, and research,

including Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, one of the editors of this book. Alongside well-known products such

as the OXO Good Grips fruit and vegetable peelers, the exhibition shows products from German manu-

facturers, including household utensils and small kitchen appliances, furniture, sanitary products, prod-

ucts for public spaces, various electrical tools, and a hands-free phone system (see Figs.13.1 to 13.7).

In general, the field of sanitary products can be considered the one in which UD is most firmly

established. HEWI Heinrich Wilke GmbH may be considered the first company in this area to have

consistently applied UD or accessibility in developing and marketing its products. But most other

manufacturers also have products that meet UD criteria. Added safety for all users is provided by

bathroom systems, such as the Variogrip system by Erlau AG and slip-resistant flush-floor showers,

such as those by Atlantis System GmbH (see Figs. 13.4 and 13.7).

FIGURE 13.1 Washing machine by BSH Bosch and Siemens Hausgeräte

GmbH. The ergonomically designed control panel of this washing machine

is on the front top of the machine, so that the drum door is higher and more

accessible, which makes loading and unloading easier.

Long description: This picture shows a washing machine by BSH

Bosch und Siemens Hausgeräte GmbH. Its ergonomically designed

control panel is on the front top user-facing corner of the machine,

allowing for a higher, and thus more accessible, placement of the drum

door, which makes loading and unloading easier. The washing program

is selected with a rotating dial on the right side of the panel, and there

is a line of clearly marked buttons in the middle of the panel that access

additional functions.

FIGURE 13.2 Easy Store Refrigerator by BSH Bosch and

Siemens Hausgeräte GmbH. The Easy Store Refrigerator is

equipped with pullout storage shelves, so that food stored at

the back can be easily retrieved. This eases handling and acces-

sibility.

Long description: This picture shows the front end of an open

refrigerator, designed by BSH Bosch und Siemens Hausgeräte

GmbH. Unlike common static refrigerator shelves, these shelves

pull out so that the food at the back of each shelf can be easily

accessed.

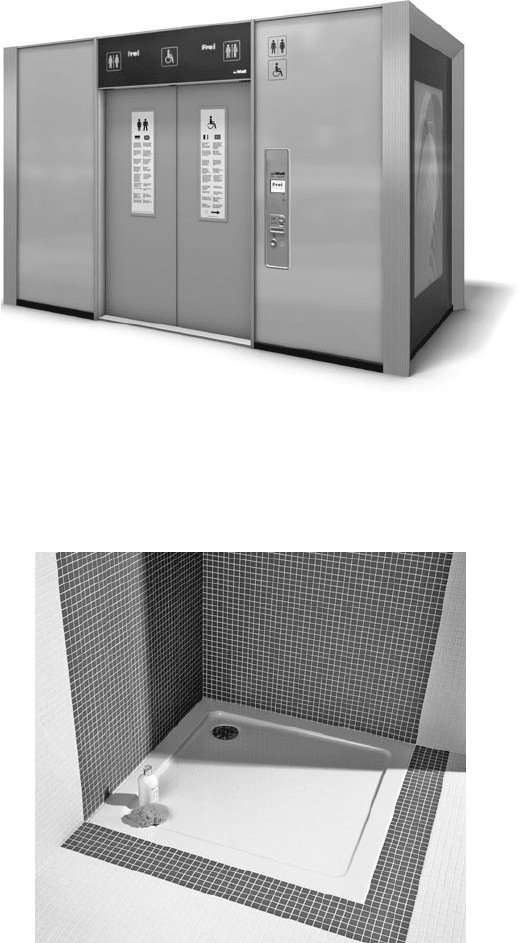

FIGURE 13.3 City Toilet Campo 2=1 by Wall AG. Wall AG’s fully automated and

self-cleaning City Toilet was awarded the “Barrier-free Berlin” designation in April

2008. The toilet is a good example of urban development in accordance with the ideas

of universal design.

Long description: This picture shows the front of an automated, self-cleaning city

toilet designed by Wall AG that is accessible by persons with disabilities, including

those in wheelchairs and visually impaired people.

FIGURE 13.4 BFD Floor-Flush Shower by Atlantis System GmbH.

The acrylic shower tub is flush with the tiles, making it easy for people

of all ages to get in and out, since there is no lip to step over. The sur-

faces are equipped with slip-resistant strips.

Long description: This picture shows an acrylic shower tub, better

described as a shower surface, since it is flush with the bathroom tile

floor and has no lip to step over. This was designed by Atlantis System

GmbH. The flush-floor design makes shower access easy for people of

all ages. Additionally, the shower surface is equipped with slip-resistant

strips, reducing the likelihood that users will lose their footing.

13.5