Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

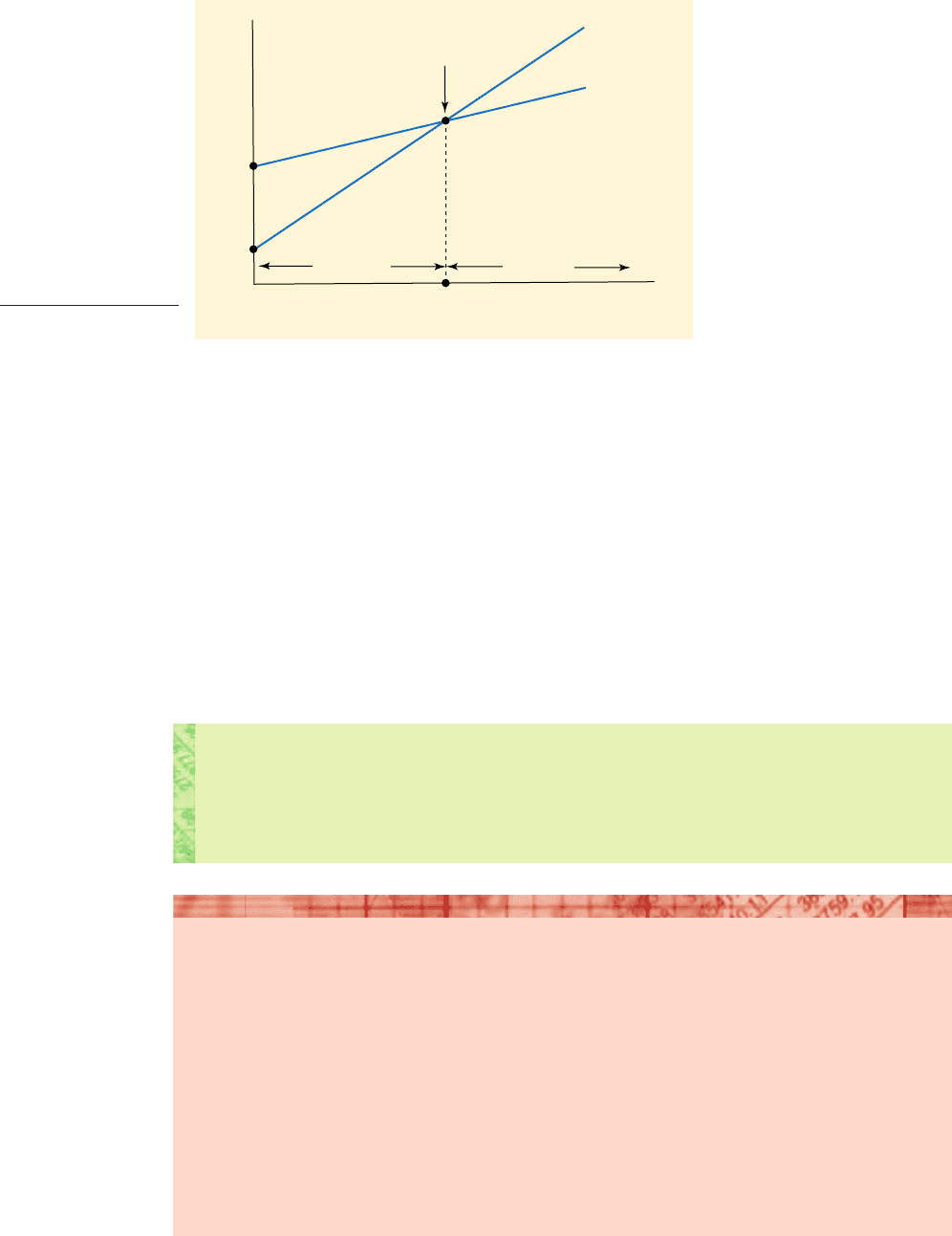

Chapter 22 Foreign investment decisions 635

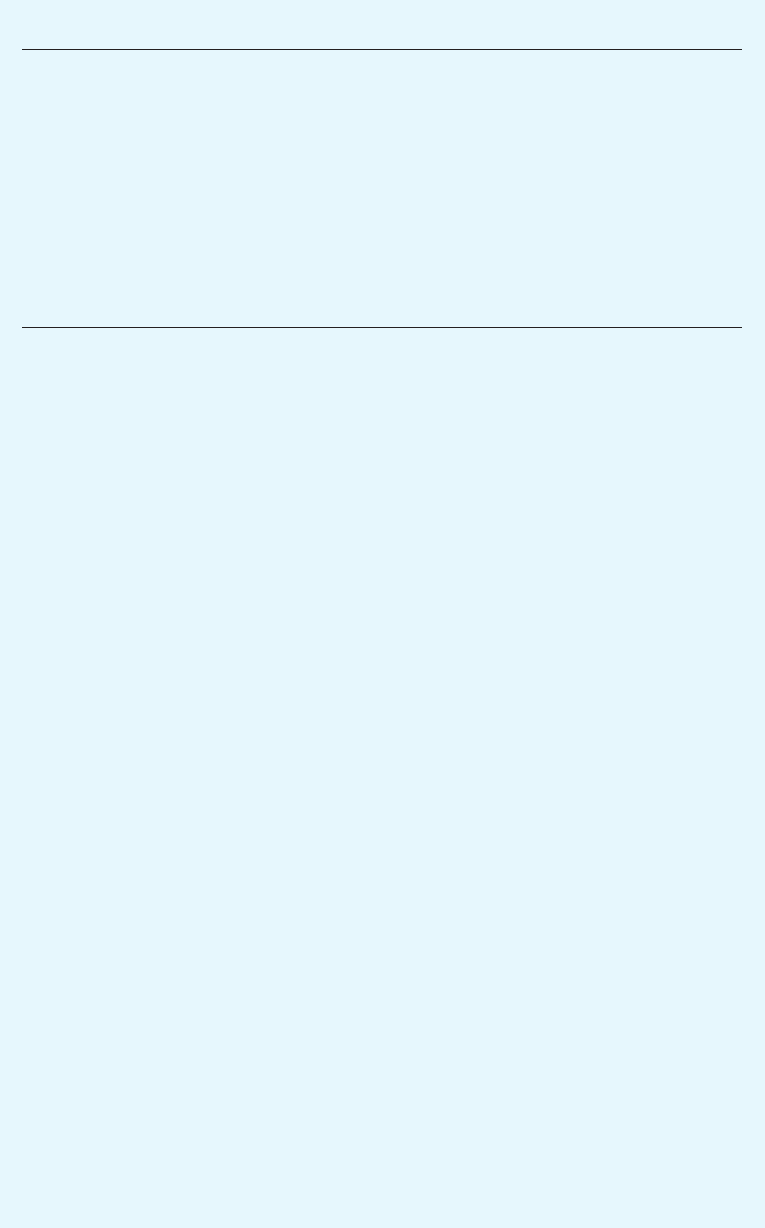

Self-assessment activity 22.2

Consider how licensing would fit into Figure 22.2 – i.e. what is its likely cost structure rela-

tive to exporting and FDI?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

Switch point

Exporting

cheaper

FDI

cheaper

Exporting

FDI

Market size

A

B

0

Q

Total cost of oper

ation

Figure 22.2

Exporting vs. FDI

These activities have quite different cost structures:

■ Exporting involves relatively low fixed costs (OA) and relatively high unit variable

costs, witness its steeper Total Cost profile.

■ FDI involves relatively high investment fixed costs (OB) and relatively low variable

costs due to lower production and distribution costs, reflected in a flatter TC profile.

For relatively low volumes, exporting may be more appropriate but the firm will even-

tually encounter a ‘crossover’ point where it becomes cheaper to switch to FDI. The

switchover occurs at market size OQ. Below this, exporting involves lower total oper-

ating costs, but beyond OQ, a switch to FDI becomes preferable.

In practice, the switch decision is less clear-cut. Switchover costs would ‘step’ the

FDI function, and most firms would wait a while before switching to ascertain

whether the market expansion was permanent. Moreover, some firms ‘jump’ the inter-

mediate stages if the foreign market size is already deemed sufficiently large.

Nalco plans $2 billion smelter in Qatar

India group’s first overseas venture

National Aluminum Company, India’s state-owned metals group, is in advanced talks with the

government in Qatar and Japanese investors to set up a $2 billion smelter in the Gulf state.

The project, which will be finalised this year, would be Nalco’s first overseas venture.

It would use its surplus alumina from India and Qatar’s cheap and abundant supply of gas-

based power to make aluminium for export.

The talks come as the company is preparing for privatisation this summer.

Initially, 30 per cent of the group will be sold through an issue of depository receipts,

expected to raise between $250 million and $300 million.

Continued

Source: Buckley and Casson (1981).

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 635

.

636 Part VI International finance

22.5 COMPLEXITIES OF FOREIGN INVESTMENT

Evaluation of foreign direct investment decisions is not fundamentally different from

the evaluation of domestic investment projects, although the political structures, eco-

nomic policies and value systems of the host country may cause certain analytical prob-

lems. There is evidence (Robbins and Stobaugh, 1973; Wilson, 1990; Neale and Buckley,

1992) that the majority of MNCs use essentially similar methods for evaluation and

control of capital investment projects for overseas subsidiaries and for domestic opera-

tions, although they may well apply different discount rates.

Appraising foreign investment involves complexities not encountered in evaluating

domestic projects. Here are the main ones:

1 Fluctuations in exchange rates over lengthy time periods are largely unpredictable.

On the one hand, these may enhance the domestic currency value of project cash

flows, but depreciation of the currency of the host country will reduce the domes-

tic currency proceeds.

2 A foreign investment project may involve levels of risk quite different from those of

the equivalent project undertaken in the domestic economy. This poses the problem

of how to estimate a suitable required rate of return for discounting purposes.

3 Once up-and-running, the foreign investment is exposed to variations in economic

policy by the host government (e.g. tax changes), which may reduce net cash flows.

4 Investment incentives provided by the host country government; e.g. in 2004, estab-

lished members of the EU such as Germany and France, with tax rates on corporate

profits of 38.3 per cent and 34.3 per cent respectively, were becoming increasingly

concerned by the lower tax rates in new member countries such as Poland (19 per

cent), Slovakia (19 per cent), Hungary (16 per cent) and Estonia, which levies no tax

on retained profits.

5 Overspill effects on the firm’s existing operations; e.g. goods produced overseas

may displace some existing sales.

6 The host government may block the repatriation of profits to the home country. A

project that is inherently profitable may not be worth undertaking if the earnings

cannot be remitted. This raises the issue of whether the evaluation should be con-

ducted from the standpoint of the subsidiary (i.e. the project itself), or from that of

the parent company. But for a company pursuing shareholder value, the relevant

This will be followed about 18 months later by the sale of another 30 per cent stake to a

strategic partner, possibly to Pechiney of France, cutting the government’s holding from 87.1

per cent to 26 per cent.

China refinery

Separately, Nalco executives will this week visit China, where the company is considering

building a refinery.

China’s domestic aluminium market is growing by 10–15 per cent a year, fuelled by restruc-

turing of businesses and fast economic growth.

Nalco wants to capture this demand by exporting its surplus alumina to refine at a smelter

it would build in China, possibly with Pechiney.

The company is already working on expanding its mines, alumina refinery and smelter in

Orissa in a plan designed to lift total alumina capacity from 1.57 million tonnes to 2.1 million

tonnes a year.

Some of the increased output of the finished metal will be absorbed in India, where the alu-

minium market is growing but could weaken as the economy continues to lose pace.

Source: Based on article by Khozem Merchant and Kunal Bose, Financial Times, 21 March 2002.

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 636

.

Chapter 22 Foreign investment decisions 637

Self-assessment activity 22.3

How does FDI differ from domestic investment?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

evaluation is from the parent’s standpoint. Some companies have adopted ingen-

ious ways of repatriating profits. Pepsico, which invested in a bottling plant in

Hungary, found it difficult to repatriate profits from this operation. To overcome

this problem, it financed the local shooting of a motion picture (The Ninth

Configuration), which was then exported to the West. (It was not a box-office hit.)

Usually, only remittable cash flows (whether or not they are actually repatriated)

should be considered, and the project accepted only if the NPV of the cash flows avail-

able for investors exceeds zero. Thus items like management fees, royalties, interest on

parent company loans, dividend remittances, and loan and interest payments to the

parent should all be included. In effect, a two-stage analysis is applied:

(i) specify the project’s own cash flows.

(ii) isolate the cash flows remittable to the parent.

Due allowance should be made for taxation in the foreign location.

■ Overcoming exchange controls

Possible ways of minimising the impact of controls over cash repatriation include:

(i) paying interest on loans or dividends on equity. Maximising dividend flows may

involve ‘creative accounting’ to inflate the local profits, although this may be

counter-productive if local tax rates exceed those in the home country. It may also

antagonise local interests.

(ii) paying royalty fees where the foreign project utilises any process over which the

parent claims proprietary rights, e.g. control of a patent or trade mark, such as Levis.

(iii) transfer pricing policies that involve charging the overseas subsidiary high prices

for components and other supplies.

(iv) applying a management charge if the senior managers are seconded from the par-

ent. Similar charges can be used to make the foreign subsidiary pay for other

services provided by the parent, e.g. IT and treasury costs. However, this may

provoke close scrutiny by the host authorities.

22.6 THE DISCOUNT RATE FOR FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI)

Opinions differ as to the appropriate discount rate to apply when discounting net cash

flows from foreign investment. ‘Gut feelings’ may suggest that FDI should be evaluat-

ed at a higher discount rate than domestic investment ‘simply because it involves more

risk’. But is this valid?

Assuming all-equity finance, two commonly-suggested possibilities are:

■ Use a required return based on the risk of similar activities in the home country.

This would be the equity cost for projects in activities similar to existing ones, or a

‘tailored’ project-specific rate for ventures into new spheres.

■ Use a required return comparable to that of local firms.

Before deciding which approach is preferable, there are several issues to consider:

1 Foreign projects generally involve higher levels of risk than domestic ones.

However, much of this risk can be dealt with in better ways than simply ‘hiking’ the

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 637

.

638 Part VI International finance

Example: Malaku mining

Malaku Mining is the newly-formed Indonesian subsidiary of Mowmack plc, an all equity-

financed UK firm, whose shares have a Beta value of 0.9 relative to the UK market portfo-

lio. The total risk (standard deviation) of the Malaku project is 30 per cent and the risk of

the Jakarta Stock Exchange is 20 per cent. The UK stock market has a 50 per cent correla-

tion with the Jakarta market.

Here, the parent Beta of 0.9 is inappropriate. Instead of using this value, it is more appro-

priate to consider the risk of the proposed activity in relation to the local market and allow

for the low correlation between the London and Jakarta exchanges. We can do this by using

a variation of the formula found in Section 10.5:

This yields a project-specific Beta of:

The cost of equity would be calculated using the UK risk-free rate of, say, 5 per cent and

the UK-equity market risk premium of, say, 5 per cent, as the firm has a UK investor base.

Hence, the required rate of return for all-equity funding would be found from the usual

CAPM formula:

k

e

R

f

Beta3ER

m

R

f

4 5% 0.7535% 4 8.75%

10.5 30%>20%2 10.5 1.52 0.75

Project Beta correlation coefficient 1risk of the activity>local market risk2

Self-assessment activity 22.4

An ungeared UK firm, with a Beta of 1.4, plans to invest in an emerging country that has

no slock exchange. Its economy has a weak correlation (0.4) with the UK. Due to operat-

ing gearing, the foreign project is 25 per cent more risky than the UK parent. The risk-free

rate is 5 per cent and the expected overall return on the UK stock market is 11 per cent

p.a. What return should the UK firm seek on this project?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

22.7 EVALUATING FDI

Under certain conditions, analysing foreign project cash flows will yield the same result

as analysing the cash flows to the parent. The key conditions are:

(i) Exchange rates adjust to reflect inflation differences between the parent country

and the foreign location, i.e. PPP applies.

discount rate. For example, currency risk can be handled by the sort of hedging

techniques mentioned in Chapter 21 (if thought necessary), and political risk can be

handled in the ways discussed later.

2 Although the total risk of FDI is often very high, the relevant risk is generally much

lower, and sometimes lower than for comparable investment at home. FDI involves

diversifying into overseas markets in the same way as an investor might diversify

shareholdings across international markets. Solnik (1974) showed that the correla-

tion between national stock markets is generally much less than one (although it

may have increased in recent years). If investors can lower relevant risk by cross-bor-

der portfolio diversification, why should firms not do so? This is especially relevant

for firms whose investors cannot diversify internationally, due to exchange controls

or transactions costs, or into countries where no organised stock exchange operates.

The relevant Beta value for, say, a UK firm operating abroad may not be the Beta cal-

culated by reference to the UK market portfolio, but the Beta in relation to the local

market (if there is one). Consider the following example.

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 638

.

Chapter 22 Foreign investment decisions 639

(ii) Project cash inflows and outflows move in line with prices in general in both

locations.

(iii) No tax differentials exist between the two countries.

(iv) No exchange controls.

Because these conditions probably will not apply in practice, the following steps are

generally recommended:

1 Predict local cash flows in money terms, i.e. including local inflation.

2 Allow for any ‘overspill’ effects like the ‘cannibalisation’ of existing exports. The

opportunity cost is neither the sales revenue nor indeed the profit lost, but the gross

margin or contribution.

3 Calculate the project’s NPV using a discount rate reflecting the cost of finance in

host country terms.

4 Allow for any management charges and royalties.

5 Estimate parent company cash flows by applying the expected future exchange rate

to host country cash flows if there are no blocks on remittances, or to net remittable

cash flows if exchange controls operate.

6 Allow for both local and parent country taxation.

7 Calculate the project’s NPV.

■ Differences between host and parent country taxation

Quite apart from different tax rates, taxation issues can complicate FDI in several ways,

most notably, if there are different systems of investment incentives in the two coun-

tries, and whether or not a Double Taxation Agreement (DTA) operates. Under a DTA,

tax paid in the host country is credited in calculating tax in the parent country. The gen-

erally-recommended procedure is to:

1 Allow for host country investment incentives before applying the local tax rate to

local cash flows.

2 Apply the relevant UK rate of tax to remitted cash flows only.

3 Adjust stage 2 for any double tax rules. For example, with a DTA and host country

tax payable at 15 per cent and where the rate of tax applicable in the UK is 30 per

cent, the relevant rate of tax to apply to remittances is 130% 15%2 15%.

Self-assessment activity 22.5

A UK MNC earns cash flow (all taxable) of $100 million in the USA. What is its overall tax

bill if the rate of tax on profits in both the USA and the UK is 30 per cent and a DTA

applies?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

A full examination of the complexities of FDI is beyond our scope. However, sever-

al of these features are brought out in the example below.

Example: Sparkes plc and Zoltan Kft

A UK company, Sparkes plc, is planning to invest £5 million in the Zoltan consumer elec-

tronics factory in Hungary. The project will generate a stream of cash flows in the local cur-

rency, Forints, which have to be converted into sterling as in Table 22.1. Should Sparkes

invest?

Continued

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 639

.

640 Part VI International finance

First, we must consider the time dimension. The project is capable of operating for ten

years, but the host government has expressed its desire to buy into the project after four years.

This may signal to Sparkes the possibility of more overt intervention, possibly extending to

outright nationalisation, perhaps by a successor government. It seems prudent to confine the

analysis to a four-year period and to include a terminal value for the project based on net

book values. If we assume a ten-year life, straight-line depreciation and ignore investment in

working capital, the NBV after four years will be 60 per cent of Half of

this can be treated as a cash inflow paid by the host government and half as a (perhaps con-

servative) assessment of the value of Sparkes’ continuing stake in the enterprise.

In practice, we often encounter complications in assessing terminal values. For example,

the assets may include land, which may appreciate in value at a rate faster than general

price inflation. If so, there may be holding gains to consider, gains which may well be tax-

able by the host government. However, it is unwise to rely overmuch on terminal values –

if project acceptance hinges on the terminal value, it is probably unwise to proceed with

this sort of project.

Second, how should we specify the cash flows? Here, we have two problems: first, diver-

gence between UK and Hungarian rates of inflation; and second, the need to convert locally-

denominated cash flows into sterling. To be consistent, we should discount nominal cash

flows at the nominal cost of capital or real cash flows at the real cost. Each will give the

same answer, but we conduct the analysis in nominal cash flows, thus incorporating the

effect of inflation. Hence all cash flows are inflated at the anticipated Hungarian rate of

inflation of 25 per cent.

As it is assumed that we are evaluating this project from the standpoint of Sparkes’ own-

ers, we need to obtain a sterling NPV figure. There are two ways of doing this.

The inflated cash flows in HUF are shown in Table 22.2. These are converted into ster-

ling using forecast future spot rates. According to PPP, sterling will appreciate by the ratio

of the respective inflation rates, i.e. (1.25)/(1.05) = 19% p.a. The predicted future spot rates

are also shown in Table 22.2. The resulting sterling cash flows are then discounted at 10%

to obtain a positive NPV.

Alternatively, we could proceed by discounting the inflated cash flows at a discount rate

applicable to a comparable firm in Hungary, thus arriving at an NPV figure in local cur-

rency, and then convert to sterling. The local discount rate using the Fisher formula (I

H

=

Hungarian inflation) is:

(1 + P)(1 + I

H

) – 1 = (1.10)(1.25) – 1 = (1.375 – 1) = 0.375, i.e. 37.5%.

To obtain a Sterling NPV, we adjust the NPV in HUF terms at today’s spot rate of 200HUF

vs. £1. Table 22.3 shows the result of this operation. Allowing for rounding, the NPVs are

identical, i.e. the project is worth £2.18 m to Sparkes’ shareholders.

Ft1,000 m Ft600 m.

■ Expected net cash flows from Zoltan in millions of Hungarian Forints (HUF) (at current

prices):

Year 0 1 2 3 4

■ The project may operate for a further six years, but the local government has expressed

its desire to purchase a 50 per cent stake at the end of Year 4. The purchase price will

be based on the net book value of assets.

■ The spot exchange rate between sterling and Forints is 200 per £1. The present rates of

inflation are 25 per cent in Hungary and 5 per cent for the UK. These rates are expected

to persist for the next few years.

■ For this level of risk, Sparkes requires a return of 10 per cent in real terms.

4004004004001,000

Table 22.1 Sparkes and Zoltan: project details

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 640

.

Chapter 22 Foreign investment decisions 641

Un-inflated Inflated Forecast future Cash flows

cash flow at 25% spot rates: in Sterling PV in

Year in HUFm (HUFm) HUF vs. £1 (£m) £m @ 10%

0 (1,000) (1,000) 200 (5.00) (5.00)

1 400 500 238 2.10 1.91

2 400 625 283 2.21 1.83

3 400 781 337 2.32 1.74

4 400 977 401 2.44 1.67

4 600* 600 401 1.50 1.02

NPV = +2.17

i.e. +£2.17m

*not inflated

Year Inflated cash flows (HUFm) PV in HUFm @ 37.5%

0 (1,000) (1,000)

1 500 364

2 625 331

3 781 300

4 977 273

4 600 168

NPV = 436

In sterling, @ spot of = 436/200 = £2.18m

200HUF vs. £1

Table 22.2 Evaluation of the Zoltan project

Table 22.3 Alternative evaluation of the Zoltan project

■ The two equivalent approaches: which is best?

Say a UK firm is investing in Canada. The two approaches are:

A The predicted C$ cash flows are converted to sterling cash flows, using expected

future spot rates. These sterling cash flows are discounted at the sterling discount

rate to yield a sterling NPV, numerically the same as in Approach B.

B The cash flows denominated in C$ are discounted at the local Canadian discount

rate to generate a C$ NPV. This is then converted at the current spot rate for C$

against sterling to yield a sterling NPV.

Each approach has the same departure point, i.e. the C$ cash flows, and ends up at

the same place, i.e. the sterling NPV. Which approach is ‘better’? This depends on

what information is available. Both approaches require forecasting cash flows in C$,

so forecasts of Canadian inflation are required. Beyond this, it depends whether the

financial manager is happier in forecasting future FX rates than in forecasting the

required return in local currency terms. Approach B requires merely a one-year fore-

cast of FX rates to derive the required return in C$ terms, whereas Approach A

requires forecasts of FX rates over all future years of the project.

Remember that the equivalence of each approach depends on several factors, in par-

ticular, operation of PPP and the existence of project inflation rates similar to those expe-

rienced at the national economy level. PPP ensures that if, say, the Canadian inflation rate

exceeds the UK rate, the exchange rate of C$ vs. sterling will deteriorate, i.e. sterling will

strengthen to ensure the parity of purchasing power of each currency in each country.

Either approach is acceptable, although the first is preferable as it has the advantage

of allowing cash flows to be adjusted at inflation rates specific to the project where these

may differ from the national rate, although this does require more detailed forecasting.

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 641

.

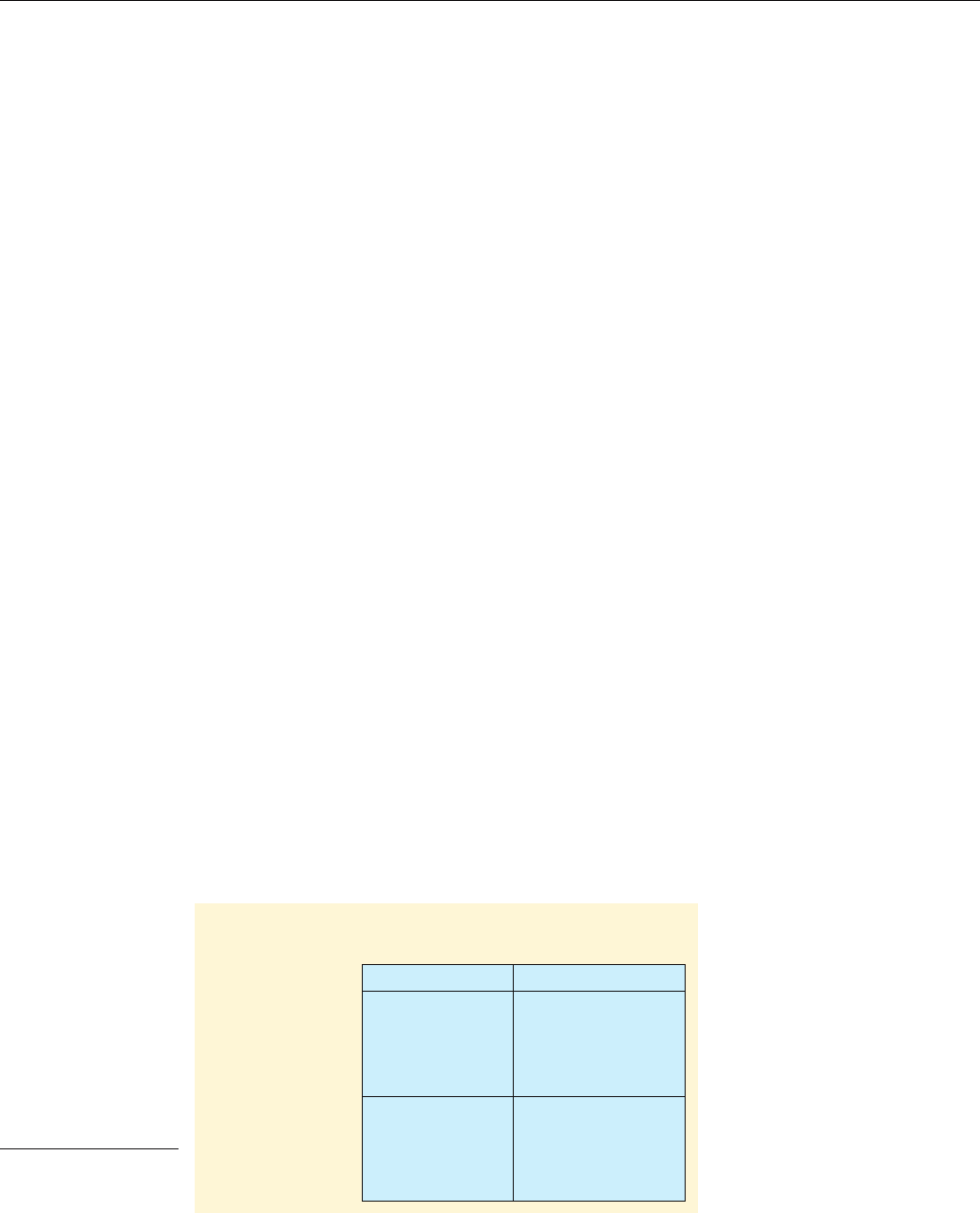

642 Part VI International finance

Sensitivity of cash outflows

to FX variations

Sensitivity

of cash inflows

to FX variations

High Low

–

LOW EXPOSURE

–

HIGH EXPOSURE

–

LOW EXPOSURE

–

HIGH EXPOSURE

High

Low

DOMESTIC TRADERS

GLOBALS EXPORTERS

IMPORTERS

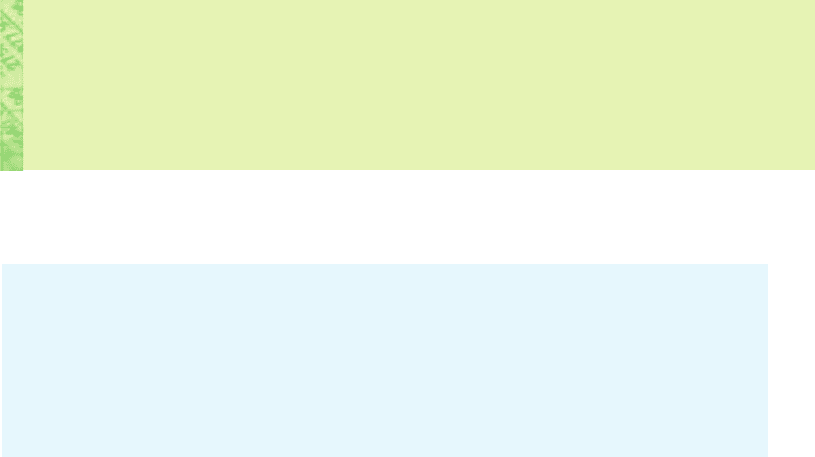

Figure 22.3

Classification of firms

by extent of operating

exposure

22.8 EXPOSURE TO FOREIGN EXCHANGE RISK

You may appreciate now that FX variations are not always disastrous. The extent of FX

exposure, and thus the urgency of dealing with it, depends on the structure of the firm’s

net cash flows in terms of its FX denomination. Firms with naturally-hedged cash flows

may be relatively unconcerned by FX variations. However firms differ in the extent to

which they are naturally hedged.

■ The four-way classification

Figure 22.3 shows a schema for classifying the extent of a firm’s exposure to FX varia-

tions. Essentially, this depends on the sensitivity of their domestic currency cash flows

to FX movements. Net cash inflows are broken down into their revenue and operating

cost components, in order to focus on firms’ net exposure. Classified by corresponding

sensitivity, the four types of firm are:

■ Domestics generate little or no income from abroad and source mainly from local

suppliers. Their net exposure is indirect and usually low, stemming from the expo-

sure suffered by their competitors on the UK markets and by their local suppliers.

■ Exporters source mainly from their own country, have high direct net exposures as

their cash inflows and outflows are not naturally hedged, being in different curren-

cies. They might consider adjusting their operating and/or financial strategies to

achieve more insulated positions.

■ Importers are in a similar position to exporters but in reverse – their net exposure is

high because they source from abroad and sell on domestic markets.

■ Globals have the lowest, and often minimal, net exposure. They have structured

their operations so as to match as far as possible the currencies in which their

inflows are denominated with those in which they incur costs. The match may not

be perfect, given the indivisibility of some types of operation, e.g. production facil-

ities, but regarding the overall profile of activities, their portfolios of cash inflow

currencies should correlate highly with their portfolios of outflow currencies. At the

group level, global firms should have little concern about FX exposures.

This is a powerful set of distinctions, but is counter-intuitive to many people. Firms

heavily engaged in foreign operations may actually have low net exposures while

many domestics, blissfully thinking they are insulated from overseas-generated expo-

sures may, in reality, be more highly exposed. A high indirect exposure could conceiv-

ably outweigh a low direct exposure.

■ Operating/economic/strategic exposure

If PPP always worked, forecasting FX rates would be very simple – in practice, prolonged

uncertainty over future exchange rates and thus the effect on the firm’s future cash flows

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 642

.

Chapter 22 Foreign investment decisions 643

in domestic currency terms greatly concerns many financial managers. The longer the

time horizon that the firm works to, the greater is its concern. Continuing exposure over

a period of years is called economic exposure. This refers to the effect of changing FX

rates on the value of a firm’s operations, generally the result of changing economic and

political factors, hence the alternative label operating exposure. Because these variations

will also affect the firm’s competitive position, and because protecting or enhancing that

position often provokes a change in strategy, it is also called strategic exposure.

These three terms are often used as synonyms. Whatever we call it, the impact is felt

on the present value of the firm’s operating cash flows over time, and thus the value

of the whole enterprise. To prevent or mitigate damage, the firm can adopt various

strategies to protect its inherent value. Measurement of exposure is the first step.

■ Measuring operating exposure

Operating exposure is both direct and indirect. Firms are concerned not only about how

FX changes affect their own cash flows, but also how their competitors are affected by

these changes. If the Chinese yuan declines against the US dollar, this may seem of no

great consequence to a UK firm that sources in the US. However, it becomes important

if, for example, competitors in the US that import from China see their import costs fall.

These indirect effects are part of a firm’s overall exposure.

Measurement of operating exposure thus involves identification and analysis of all

future exposures both for the individual firm and also its main competitors, actual and

even potential ones, bearing in mind that FX changes may even entice new entrants

into existing markets.

It is worth repeating that operating exposure is concerned less with expected changes

in FX rates, because, in efficient financial markets, both managers and investors will have

already incorporated these into their anticipation of parent company currency cash flows.

If the markets expect sterling to decline vs. the US dollar, the likely higher future sterling

cash inflows of UK firms that export to the USA will have been factored into company

valuations. In this situation, it is generally advisable to incorporate the forward rate of

exchange into projections for future planning purposes. The damage is done when expec-

tations are not fulfilled and/or when changes result from totally unexpected factors.

Example: Pitt plc

Pitt plc produces half its output in the USA, valued at today’s exchange rate (US$1.50 vs.

) at million. The other half is sold in the UK. About 25 per cent of Pitt’s supplies are

sourced from the USA, valued at million. Labour costs are £10 million per annum, and

cash overheads are million per annum. Shareholders require a return of 12 per cent per

annum.

Required

(a) Determine the present value of Pitt’s operating cash flows in sterling terms over a 10-

year time horizon.

(b) Identify Pitt’s direct and indirect operating exposures.

(c) What is the effect on Pitt’s PV if the sterling/dollar exchange rate changes to US$1.40

vs.

Solution

(a) At the present exchange rate, Pitt’s cash flows are:

■ Cash inflows:

■ Cash outflows:

Supplies

Labour

Overheads

Net Cash Flow

Continued

£125 m

1£5 m2

1£10 m2

1£60 m214 £15 m p.a.2

£200 m2 £100 m p.a.

£1?

£5

£15

£100£1

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 643

.

644 Part VI International finance

(b) Direct exposures:

■ 50 per cent of cash inflows are exposed.

■ 25 per cent of payments to suppliers are exposed.

■ Any US$ content of labour input and cash overheads would also be exposed.

Indirect exposures stem from the extent to which:

■ US competitors are exposed to currency fluctuations.

■ US suppliers are exposed.

■ UK competitors are exposed.

■ UK suppliers are exposed.

As discussed, it is important to realise that overall exposures transcend variations in

the rate. If, for example, suppliers in the UK import from India, they face expo-

sure from the exchange rate of the rupee vs. sterling. Adverse variations are likely to

spur them to recoup cost increases from their customers. Obviously, the extent to which

they can achieve this depends on their own market power, e.g. the number and relative

size of their own competitors and the importance of the components to customers like

Pitt plc.

(c) Sterling depreciation to US$1.40 vs. will increase the sterling value of the net cash

inflows, because, at present, annual USD cash inflows exceed USD cash outflows. At

the current exchange rate of US$1.50 vs. the annual difference is

Revised valuation:

■ Inflows:

■ Outflows:

Supplies:

Labour

Overheads

Net Cash Inflow

■ PV @ 12% (£131 m 5.650) £740 m

In this example, depreciation of sterling by has resulted in an

increase in firm value of about 5 per cent. The sensitivity of a firm’s value will depend on

the structure of the firm’s cash inflows and outflows – the greater the net foreign currency

component, the greater the sensitivity of firm value.

11 1.40>1.502 7%

£131 m

1£5 m2

1£10 m2

1£61 m213 £15 m2 1£15 m 1.50>1.402

£207 m p.a.3£100 m 1£100 m 1.50>1.4024

ˇ £85 m p.a.

1£100 m £15 m2£1,

£1

US$>£

1£125 m 5.6502 £706 m

Present value 1£125 m 10-year annuity factor at 12%2

■ Comment

The result is somewhat oversimplified for several reasons:

It assumes no change in the volumes of US-generated business in response to ster-

ling depreciation. In reality, Pitt may lower the US$ price to stimulate sales as it can

now afford a price cut of up to 7 per cent and still achieve the same sterling cash

inflow, after converting US$ into sterling at the more favourable rate.

The effect will depend on:

(i) the extent of the price cut, i.e. whether Pitt matches the 7 per cent fall in sterling

or takes some or all of this as windfall profit.

(ii) the elasticity of US demand for the product, i.e. the extent to which demand is

stimulated by a price cut.

(iii) whether Pitt can produce enough to satisfy the demand increase.

(iv) the extent to which US competitors follow a price cut.

CFAI_C22.QXD 3/15/07 7:07 AM Page 644