Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

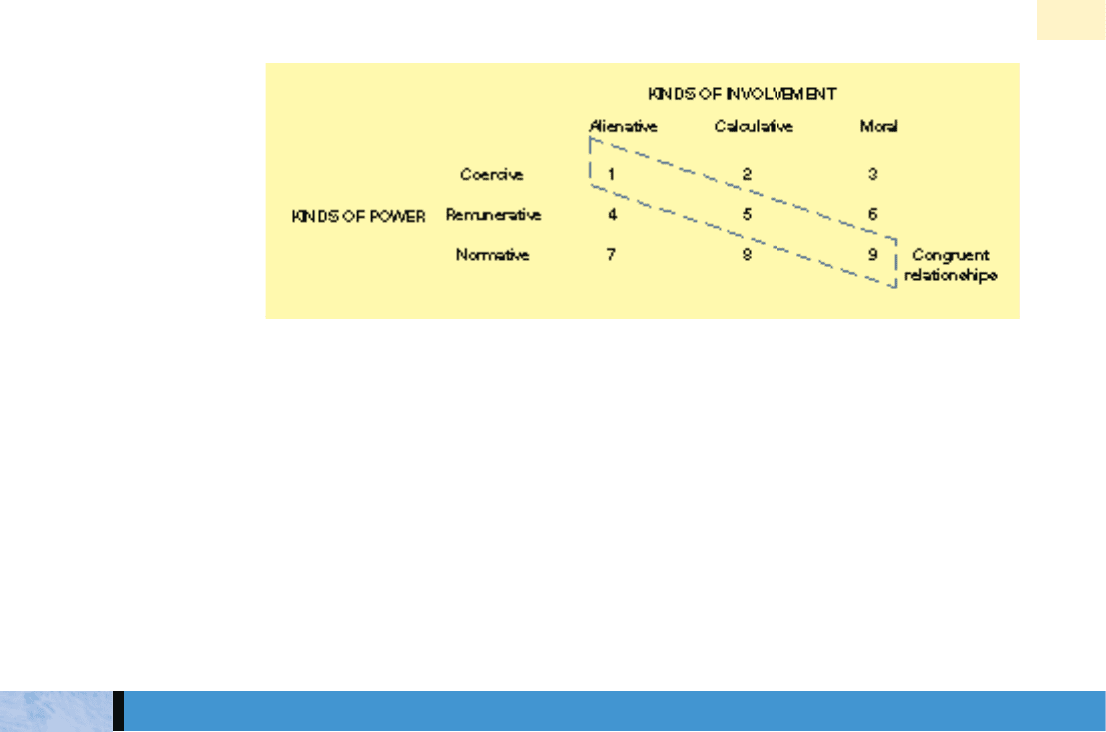

■ remunerative power with calculative involvement – relationship 5 (typified, for

example, by business firms);

■

normative power with moral involvement – relationship 9 (typified, for example, by

churches).

The matching of these kinds of power and involvement is congruent with each other,

and represents the most common form of compliance in organisations. The other six

types of organisational relationships are incongruent. Etzioni suggests that organisa-

tions with congruent compliance structure will be more effective than organisations

with incongruent structures.

There are many potential sources of power which enable members of an organisation

to further their own interests and which provide a means of resolving conflicts. Sources

of organisational power include, for example: structure, formal authority, rules and reg-

ulations; standing orders; control of the decision-making process; control of resources

and technology; control of information or knowledge; trade unions and staff organisa-

tions; gender; and the informal organisation.

46

Power can also be viewed in terms of the different levels at which it is constituted.

Fincham looks at organisational power in terms of three types or levels of analysis:

processual; institutional; and organisational.

47

■ At the processual level power originates in the process of daily interaction. The

level of analysis is that of lateral relations between management interest groups and

the basis of explanation is strategic. Processual power focuses on the ‘micro-politics’

of organisational life. It stresses power as negotiation and bargaining, and the

‘enactment’ of rules and how resources are employed in the power game.

■ At the institutional level managerial power is seen as resting on external social and

economic structures which create beliefs about the inevitability of managerial

authority. Power is explained as being ‘mandated’ to the organisation. When man-

agers seek to exercise power they can draw on a set of institutionally produced rules

such as cultural beliefs about the right to manage.

■ The organisational level stresses the organisation’s own power system and the hier-

archy as a means of reproducing power. Dominant beliefs, values and knowledge

shape organisational priorities and solutions or reflect the interests of particular

groups or functions. Those in authority select others to sustain the existing power

structure. Organisational hierarchies transmit power between the institutional inter-

ests and the rules and resources governing action.

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

845

Figure 21.4 Organisational relationships and compliance

(Reprinted with the permission of the Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster Inc., from A Comparative Analysis of Complex

Organisations Revised edition, by Amitai Etzioni. Copyright © 1975 by Amitai Etzioni.)

PERSPECTIVES OF ORGANISATIONAL POWER

Pfeffer has identified a number of critical ways in which individuals or groups may

acquire power in organisations when viewed as social entities:

■ providing resources – for example money, prestige, legitimacy, rewards and sanc-

tions, and expertise that create a dependency on the part of other people;

■ coping with uncertainty – the ability to permit the rationalisation of organisa-

tional activity, for example through standard operating procedures, or to reduce

uncertainty or unpredictability;

■ being irreplaceable – having exclusive training, knowledge or expertise that cannot

readily be acquired by others, or through the use of lack of adequate documentation

or specialised language and symbols;

■ affecting decision processes – the ability to affect some part of the decision process

for example by the basic values and objectives used in making the decision, or by

controlling alternative choices;

■ by consensus – the extent to which individuals share a common perspective, set

of values or definition of the situation, or consensus concerning knowledge and

technology.

48

All organisations have their own culture – which describes what the organisation is all about

and ‘the way things are done around here’. Culture is an important ingredient of managerial

behaviour and organisational perform-

ance. Strong organisational cultures

where individuals and the organisa-

tion share the same goals (for example

IBM, Marks & Spencer, Mercedes-

Benz and The Body Shop) will have a

significant influence on power rela-

tionships, personal values and beliefs

and the nature of organisational

politics. (Organisational culture and

climate are discussed in Chapter 22.)

Power, however, arises not only from sources of structure or formal position within the

organisation but from interpersonal sources such as the personality, characteristics and

talents of individual members of the organisation. The exercise of power is also a social

process which derives from a multiplicity of sources and situations.

49

This suggests a

more pluralistic approach and recognises power as a major organisational variable.

Many different groups and individuals have the ability to influence the behaviour and

actions of other people.

In Chapter 8 we discussed a classification by French and Raven of social power based

on a broader perception of leadership influence.

50

French and Raven identified five

main sources of power:

■ reward power

■ coercive power

■ legitimate power

■ referent power

■ expert power.

Arguably, the most important and pervasive relationships in the organisation are

those that do not rely on the exercise of formal power and position within the man-

846

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Organisational

sources of

power

Culture as a

source of power

Mercedes-Benz is a company with a strong organisational culture

PLURALISTIC APPROACHES TO POWER

Photo: Mercedes-Benz of York

agement structure.

51

For example, in Chapter 8 we also discussed charisma, or personal

power, as a feature of transformational leadership.

We can also distinguish between legitimate (organisational) power that derives from a

person’s position within the formal structure of the organisation and the managerial

hierarchy of command; or personal (informal) power that derives from the individual and

is in the eye of the beholders who believe that person has the ability to influence other

people or events and to make things happen.

Beggs suggests that although organisational power and personal power are logically

separate, they can interact.

When a person is using considerable amounts of organisational power – conferred on him or her

by status or position in the hierarchy – the effect can be to disempower an employee. It is as if an

organisation feeds off the power of its people, sucking it away. Think of it this way. Imagine the

worst kind of authoritarian manager telling someone to do a job: we might call this dictating. The

effect is familiar to us all – from school through to work we have all been dictated to. It usually

makes us feel either helpless or bloody-minded, reducing our effectiveness dramatically. That

manager is abusing power. Think now of a much more fair-minded manager, who is urging

someone to do a job. This is still telling but the effect on that person, because organisational

power is not being over-used, is less damaging. That is how organisational power and personal

power are inter-linked – through both the mindset of the manager and the interpersonal strategy

he or she uses.

52

Organisations function on the basis of networks of interdependent activities. Certain

jobs or work relationships enable people to exercise a level of power in excess of their

formal position within the structure of the organisation. A classic example is someone,

perhaps a personal assistant or office manager, who fulfils the role of gatekeeper to the

boss. There is an inherent danger with this type of role relationship that the boss may

become too dependent upon the gatekeeper. Undertaking the responsibilities delegated

by the boss and maintaining control can lead to the gatekeeper’s misuse of their role

and to an abuse of power.

Many people within organisations also have the ability to grant or withhold ‘favours’

within the formal or the informal interpretation of their job role – for example, secre-

taries, caretakers, security staff and telephonists. Staff may exercise negative power – that

is, ‘the capacity to stop things happening, to delay them, to distort or disrupt them’.

53

A

common example could be the secretary who screens and intercepts messages to the

boss, delays arranging appointments and filters mail. Negative power is not necessarily

related proportionately to position and may often be exercised easily by people at lower

levels of the hierarchical structure. Lerner gives the following example:

A retired gatekeeper who managed a large outpatient clinic gleefully confides that in her former

position as head secretary she had felt like a madam of an exclusive house of ill repute. ‘The part

of my job I enjoyed the most was matching doctor with stenographer … I was in charge of the

girls and the doctors frequently gave me gifts. If a doctor failed to reward me, he was assigned a

girl less competent. If a girl defied me I assigned her to a doctor that she didn’t like.’

54

Another example is given by Green who refers to the negative power which can be held

by comparatively junior staff. For example, the person who sorts and distributes the

incoming mail; he or she has the opportunity to use negative power by the delay or

disruption of items for reasons that may be entirely personal.

55

A reality of organisa-

tional life is the vagaries of social relationships including office politics,

56

and also the

grapevine and gossip. Although it is a difficult topic to pin down, Mann refers to the

key role that gossip plays in power relationships and knowledge production in organi-

sations and maintains that: ‘There is an undeniable relationship between knowledge

and power which lies at the root of gossiping.’

57

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

847

Organisational

and personal

power

Network of

social

relationships

Motivational need for power

Power can be a positive source of motivation for some people (see the discussion on

achievement motivation in Chapter 12). McClelland and Burnham have examined the

motivational need for power and believes that there are two major types of power: pos-

itive (social) power; and negative (personal) power. He suggests that the effective

manager should possess a high need for social power directed towards the organisa-

tion, concern for group goals and helping members to achieve those goals, and

exercised on behalf of people. Social power should be distinguished from the negative

personal power which is characterised by satisfaction from exercising tight control

over other people, and personal prestige and aggrandisement.

58

There is often a fine line between the motivation to achieve personal dominance

and the use of social power. It has to be acknowledged, however, that there are clearly

some managers who positively strive for and enjoy the exercise of power over other

people. They seek to maintain absolute control over subordinates and the activities of

their department/section, and welcome the feeling of being indispensable. The pos-

session of power is an ultimate ego satisfaction and such managers do not seem unduly

concerned if as a result they are unpopular with, or lack the respect of, their colleagues

or subordinate staff.

Stewart refers to the classic dilemma that underlies the nature of control: finding the

right balance for present conditions between order and flexibility. This involves the

trade-off between trying to improve predictability of people’s actions against the desir-

ability of encouraging individual and local responsiveness to changing situations. The

organisation may need a ‘tight–loose’ structure with certain departments or areas of

work closely controlled (‘tight’); whilst other departments or areas of work should be

left fluid and flexible (‘loose’).

59

Three main forms of control

According to Stewart, ‘Control can – and should – be exercised in different ways.’ She

identifies three main forms of control.

■ Direct control by orders, direct supervision and rules and regulations. Direct

controls may be necessary, and more readily acceptable, in a crisis situation and

during training. But in organisations where people expect to participate in decision-

making, such forms of control may be unacceptable. Rules and regulations which

are not accepted as reasonable, or at least not unreasonable, will offer some people a

challenge to use their ingenuity in finding ways round them.

■ Control through standardisation and specialisation. This is achieved through

clear definition of the inputs to a job, the methods to be used and the required out-

puts. Such bureaucratic control makes clear the parameters within which one can

act and paradoxically makes decentralisation easier. Provided the parameters are not

unduly restrictive they can increase the sense of freedom. For example, within

clearly defined limits which ensure that one retail chain store looks like another,

individual managers may have freedom to do the job as they wish.

■ Control through influencing the way that people think about what they should

do. This is often the most effective method of exercising control. It may be achieved

through selective recruitment of people who seem likely to share a similar approach,

the training and socialisation of people into thinking the organisation’s way, and

through peer pressure. Where an organisation has a very strong culture, people who

848

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

THE BALANCE BETWEEN ORDER AND FLEXIBILITY

do not fit in, or learn to adapt, are likely to be pushed out, even though they may

appear to leave of their own volition.

Stewart also refers to a second, related dilemma of finding the appropriate balance

between centralisation, as a means of exercising control, and decentralisation.

(Centralisation and decentralisation were discussed in Chapter 15.)

The question of control versus autonomy

From their study of top performing companies in the 1990s, Goldsmith and Clutterbuck

refer to the sharing of power, and to the balance between control and autonomy. They

question how companies manage to balance giving people maximum freedom against

exerting controls to ensure the benefits of size and a common sense of direction. The

more managers share power, the more authority and resources they gained:

The way to exert the most effective control is to limit it to the few simple, readily understandable

processes that have the greatest impact on group performance, and to maximise the freedom that

managers at all levels have to achieve clear goals in their own way. And the more rigidly those core

controls are enforced, the greater are the freedoms people need in order to compensate and to

release their creativity, initiative and proactivity. Control and autonomy are therefore two sides of

the same coin … What do we mean by control and autonomy? Formal control seems to be exercised

in three main ways: through setting or agreeing targets for performance (mainly but not exclusively

financial); through measurement and reporting systems; and through certain decisions to be made

centrally or corporately. Autonomy is, in essence, an absence of formal control: once clear goals are

set, the individual manager has greater or lesser freedom to determine how they will be met. There

are still controls in place, but they are much less obvious or intrusive.

60

Discussion on the balance between order and flexibility, and control versus autonomy,

draws attention to the importance of delegation and empowerment. The concept of

delegation may appear to be straightforward. However, anyone with experience of a

work situation is likely to be aware of the importance of delegation and the conse-

quences of badly managed delegation. Successful delegation is a social skill. Where

managers lack this skill, or do not have a sufficient awareness of people-perception,

there are two extreme forms of behaviour which can result.

■ At one extreme is the almost total lack of meaningful delegation. Subordinate staff

are only permitted to operate within closely defined and often routine areas of work,

with detailed supervision. Staff are treated as if they are incapable of thinking for

themselves and given little or no opportunity to exercise initiative or responsibility.

■ At the other extreme there can be an excessive zeal for so-called delegation when a

manager leaves subordinates to their own resources, often with only minimal guid-

ance or training, and expects them to take the consequences for their own actions or

decisions. These ‘super-delegators’ tend to misuse the practice of delegation and are

often like the Artful Dodger. Somehow, such managers often contrive not to be

around when difficult situations arise. Such a form of behaviour is not delegation, it

is an abdication of the manager’s responsibility.

Either of these two extreme forms of behaviour can be frustrating and potentially

stressful for subordinate staff, and unlikely to lead to improved organisational effec-

tiveness. The nature of delegation can have a significant effect on the morale,

motivation and work performance of staff. In all but the smallest organisation the only

way to get work done effectively is through delegation, but even such an important

practice as delegation can be misused or over-applied.

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

849

DELEGATION AND EMPOWERMENT

At the individual (or personal) level delegation is the process of entrusting

authority and responsibility to others throughout the various levels of the organi-

sation. It is arguably possible to have delegation upwards – for example, when a

manager temporarily takes over the work of a subordinate who is absent through ill-

ness or holiday. It is also possible to delegate laterally to another manager on the same

level. However, delegation is usually interpreted as a movement down the organisa-

tion. It is the authorisation to undertake activities that would otherwise be carried out

by someone in a more senior position. It does in effect change the shape – or at least

the actual operation of – the organisation structure. Downsizing and de-layering have

arguably limited the opportunities for delegation, although this may be offset by

demands for greater flexibility and empowerment. In any event, delegation is still an

essential process of management.

As Crainer, for example, points out, in the age of empowerment, the ability to dele-

gate effectively is critically important.

Delegation has always been recognised as a key ingredient of successful management and lead-

ership. But, in the 1980s delegation underwent a crisis of confidence … The 1990s saw a shift in

attitudes. No longer was delegation an occasional managerial indulgence. Instead it became a

necessity. This has continued to be the case.

61

Delegation is not just the arbitrary shedding of work. It is not just the issuing and fol-

lowing of orders or carrying out of specified tasks in accordance with detailed

instructions. Within the formal structure of the organisation, delegation creates a spe-

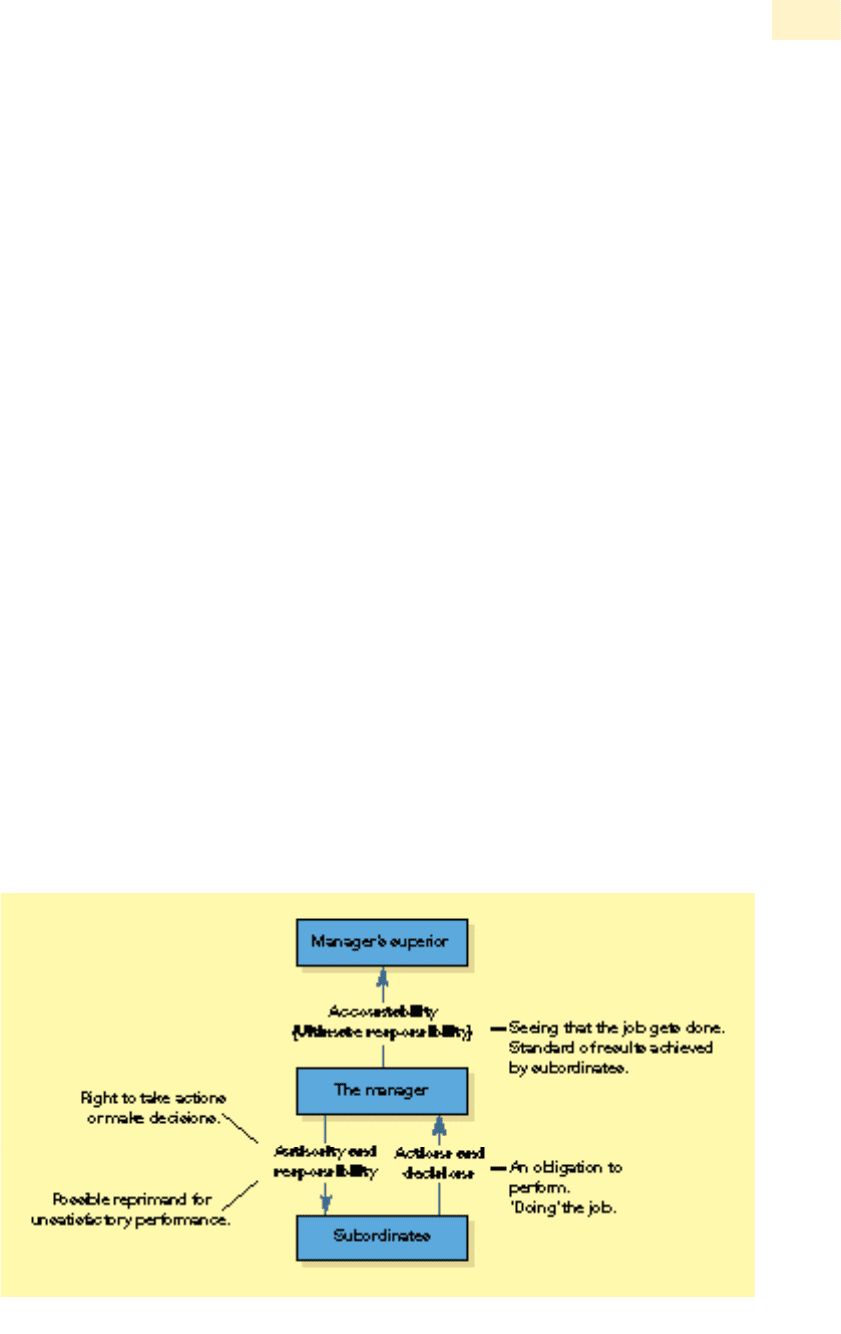

cial manager–subordinate relationship. It is founded on the concept of:

■ authority;

■ responsibility; and

■ accountability (ultimate responsibility).

Delegation means the conferring of a specified authority by a higher authority. In its essence

it involves a dual responsibility. The one to whom authority is delegated becomes responsible

to the superior for doing the job, but the superior remains responsible for getting the job

done. This principle of delegation is the centre of all processes in formal organization.

62

■ Authority is the right to take action or make decisions that the manager would other-

wise have done. Authority legitimises the exercise of power within the structure and

rules of the organisation. It enables the subordinate to issue valid instructions for

others to follow.

■ Responsibility involves an obligation by the subordinate to perform certain duties or

make certain decisions and having to accept possible reprimand from the manager

for unsatisfactory performance. The meaning of the term ‘responsibility’ is, however,

subject to possible confusion: although delegation embraces both authority and

responsibility, effective delegation is not abdication of responsibility.

■

Accountability

is interpreted as meaning ultimate responsibility and cannot be dele-

gated. Managers have to accept ‘responsibility’ for the control of their staff, for the

performance of all duties allocated to their department/section within the structure of

the organisation, and for the standard of results achieved. That is, ‘the buck stops here’.

The manager is in turn responsible to higher management. This is the essence of the

nature of the ‘dual responsibility’ of delegation. The manager is answerable to a superior

and cannot shift responsibility back to subordinates. The responsibility of the superior

850

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

THE MANAGER–SUBORDINATE RELATIONSHIP

for the acts of subordinates is absolute.

63

In order to help clarify the significance of

‘dual responsibility’ in delegation, it might be better expressed as:

The subordinate is responsible to the manager for doing the job, while the man-

ager is responsible for seeing that the job gets done. The manager is accountable

to a superior for the actions of subordinates.

Authority commensurate with responsibility

Delegation, therefore, embraces both authority and responsibility. It is not practical to

delegate one without the other. (See Figure 21.5.)

Responsibility must be supported by authority, and by the power to influence the areas

of performance for which the subordinate is to be held responsible. Authority can be dele-

gated readily, but many problems of delegation stem from failure to provide the necessary

information and resources in order to achieve expected results, or from failure to delegate

sufficient authority to enable subordinates to fulfil their responsibilities. For example, if a

section head is held responsible to a departmental manager for the performance of junior

staff but does not have the organisational power (authority) to influence their selection

and appointment, their motivation, the allocation of their duties, their training and

development, or their sanctions and rewards, then the section leader can hardly be held

responsible for unsatisfactory performance of the junior staff. To hold subordinates

responsible for certain areas of performance without also conferring on them the neces-

sary authority within the structure of the organisation to take action and make decisions

within the limits of that responsibility is an abuse of delegation.

If a manager delegates some task to a subordinate member of staff who does a bad

job, then the manager must accept ultimate responsibility for the subordinate’s

actions. It is the manager who is answerable to a superior. It is not for the manager to

say: ‘Don’t blame me boss, you don’t expect me to do everything myself. You knew I

would have to ask a member of my staff to do the work, I can’t help it if “x” did a bad

job.’ The manager should accept the blame as the person who was obligated to the

boss for the performance of the department/section, and accountable to see that the

task was completed satisfactorily. It is necessary to maintain the organisational hierar-

chy and structure of command.

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

851

Figure 21.5 The basis of delegation

Managers should protect and support subordinate staff and accept, personally,

any reprimand for unsatisfactory performance. It is then up to managers to sort out

things in their own department/section, to counsel members of staff concerned and to

review their system of delegation.

Delegation is not an easy task. It involves behavioural as well as organisational and

economic considerations, and it is subject to a number of possible abuses. Properly

handled, however, delegation offers many potential benefits to both the organisation

and staff. Delegation should lead to the optimum use of human resources and

improved organisational performance. Studies of successful organisations lend support

to the advantages to be gained from effective delegation.

64

Time is one of the most valuable, but limited, resources and it is important that the

manager utilises time to the maximum advantage. By delegating those activities which

can be done just as well by subordinate staff the manager is using to advantage the

human resources of the organisation. Managers are also giving themselves more time

in which to manage. Delegation leaves the manager free to make profitable use of time,

to concentrate on the more important tasks and to spend more time in managing and

less in doing. This should lead to a more even flow of work and a reduction of bottle-

necks. It should make the manager more accessible for consultation with subordinates,

superiors or other managers. This should also improve the process of communications.

Delegation provides a means of training and development, and of testing the subordi-

nate’s suitability for promotion. It can be used as a means of assessing the likely

performance of a subordinate at a higher level of authority and responsibility.

Delegation thereby helps to avoid the ‘Peter Principle’ – that is ‘In a hierarchy every

employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence’ (discussed in Chapter 2). If man-

agers have trained competent subordinates capable of taking their place this will not

only aid organisational progress but should also enhance their own prospects for fur-

ther advancement. Managers should therefore be encouraged to delegate in order

to make themselves dispensable.

65

As organisations become more complex, there is an increasing need for staff with spe-

cialist knowledge and skills. Delegation can encourage the development of specialist

expertise and enables specific aspects of management to be brought within the

province of a number of specialist staff for greater efficiency. This is likely to enhance

the quality of decision-making.

Another reason for delegation is the geographical separation of departments or sections

of the organisation. For example, where a branch office is located some distance away

from the head office the branch manager will need an adequate level of delegation in

order to maintain the day-to-day operational efficiency of the department or section.

Successful delegation benefits both the manager and the subordinate and enables them

both to play their respective roles in improving organisational effectiveness. It is a

principle of delegation that decisions should be made at the lowest level in the organi-

sation compatible with efficiency. It is a question of opportunity cost. If decisions are

made at a higher level than necessary they are being made at greater cost than neces-

sary. Delegation is therefore a matter of sound economics as well as good organisation.

852

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

BENEFITS OF DELEGATION

Best use

of time

A means of

training and

development

Specialist

knowledge and

skills

Geographical

location

Sound

economics

Delegation should lead to an improvement in the strength of the workforce. It should

give subordinates greater scope for action and opportunities to develop their aptitudes

and abilities, and increase their commitment to the goals of the organisation.

66

Delegation can lead to improved morale by increasing motivation and job satisfaction.

It can help satisfy the employee’s higher-level needs. Delegation focuses attention on

‘motivators’ or ‘growth’ factors and creates a climate in which subordinates can

become more involved in the planning and decision-making processes of the organisa-

tion. Delegation is a form of participation. Where subordinates are brought to accept

and welcome delegation this will encourage a positive attitude to their work and a will-

ingness to discharge their authority and responsibilities.

With so many good reasons for delegation, why is it that managers often fail to dele-

gate or do not delegate successfully? There are many factors which affect the amount

of delegation, and its effectiveness. Delegation is influenced by the manager’s percep-

tion of subordinate staff. It is also influenced by the subordinate’s perception of the

manager’s reasons for delegation. Failure to delegate often results from the man-

ager’s fear.

■ The manager may fear that the subordinate is not capable of doing a sufficiently

good job. Also, the manager may fear being blamed for the subordinate’s mistakes.

■ Conversely, the manager may fear that the subordinate will do too good a job and

show the manager in a bad light.

The manager should, of course, remember that the task of management is to get work

done through the efforts of other people. If the subordinate does a particularly good

job this should reflect favourably on the manager.

Assumptions about human nature and behaviour

A reluctance to delegate might arise from the manager’s belief in, and set of assumptions

about, human nature and behaviour.

67

The Theory X manager believes that people have

an inherent dislike of work, wish to avoid responsibility, and must be coerced, controlled,

directed, and threatened with punishment in order to achieve results. Such a manager is

likely, therefore, to be interested in only limited schemes of delegation, within clearly

defined limits and with an easy system of reward and punishment.

On the other hand, the Theory Y manager believes that people find work a natural

and rewarding activity, they learn to accept and to seek responsibility, and they will

respond positively to opportunities for personal growth and to sympathetic leadership.

Such a manager is more likely to be interested in wider schemes of delegation based on

consultation with subordinates, and with responsibility willingly accepted out of per-

sonal commitment.

An essential ingredient of effective management is the ability to put your trust in

others and to let go some of the workload.

Some managers are poor at delegation because they belong to the ‘nobody does it better school

of management’. The fact is that if they never give the job to someone else they will always be the

only person for the job. But fear together with feelings of insecurity which prevent them from let-

ting go of tasks and trusting others, makes for bad management and can lead to low morale

amongst employees. If a boss doesn’t believe someone can do the job and conveys those nega-

tive feelings, then they will probably find their low expectations are met.

68

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

853

Strength of

the workforce

REASONS FOR LACK OF DELEGATION

Dependence

upon other

people

As Stewart points out, managers who think about what can be done only in terms of

what they can do, cannot be effective. Managing is not a solo activity.

Managers must learn to accept their dependence upon people. A key part of being a good man-

ager is managing that dependence. Managers who say that they cannot delegate because they

have poor staff may genuinely be unfortunate in the calibre of the staff that they have inherited or

been given. More often this view is a criticism of themselves: a criticism either of their unwilling-

ness to delegate when they could and should do so, or a criticism of their selection, training and

development of their staff.

69

Managers may not have been ‘trained’ themselves in the skills and art of delegation.

They may lack an awareness of the need for, and importance of, effective delegation, or

what it entails. Another reason for a reluctance to delegate may, in part, be due to the

fact that throughout childhood and in college life delegation is usually discouraged.

There are few opportunities to learn how to delegate. Hence when people first become

managers they tend to display poor delegation skills.

70

The opportunities for delega-

tion are also affected by a number of organisational factors, discussed in Chapter 16.

In order to overcome the lack of delegation and to realise the full benefits without loss

of control, it is necessary to adopt a planned and systematic approach. Setting up a

successful system of delegation involves the manager examining four basic questions.

■ What tasks could be performed better by other staff?

■ What opportunities are there for staff to learn and develop by undertaking delegated

tasks and responsibilities?

■ How should the increased responsibilities be implemented and to whom should

they be given?

■ What forms of monitoring control system would be most appropriate?

In order to set up an effective system of delegation, subordinates should know exactly

what is expected of them, what has to be achieved, the boundaries within which they

have freedom of action, and how far they can exercise independent decision-making. It

is possible to identify six main stages in a planned and systematic approach to delega-

tion (see Figure 21.6):

■ clarification of objectives, and suitable patterns of organisation;

■ agreement on terms of reference, and acceptance of authority and responsibility;

■ guidance, support and training, and patterns of communication;

■ effective monitoring and review procedures;

■ freedom of action within agreed terms of reference; and

■ related reward system.

The first stage in a planned and systematic approach to delegation is the clarification

of objectives and the design of suitable patterns of organisation to achieve these objec-

tives. Policies and procedures must be established and defined in order to provide a

framework for the exercise of authority and the acceptance of responsibility. Managers

must be clear about their own role, and the opportunities and limitations of their own

jobs. There must be a clear chain of command with effective communications and co-

ordination between the various levels of authority within the organisation structure.

The manager can then negotiate and agree the subordinate’s role prescription and terms

of reference. Those areas of work in which the subordinate is responsible for achieving

results should be identified clearly. Emphasis should generally be placed on end-results

rather than a set of detailed instructions. It is important to make sure that subordi-

854

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Lack of training

A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO DELEGATION

Clarification of

objectives and

organisation

Agreement on

terms of

reference