Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

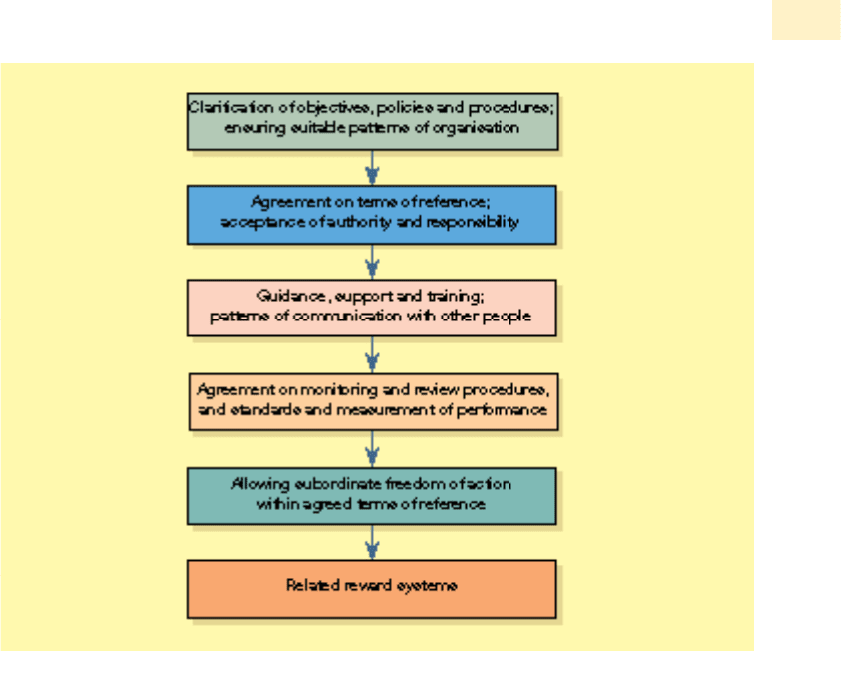

nates accept the extent of, and any restrictions on, the authority and responsibility

delegated to them. Subordinates should feel a sense of commitment to their new tasks

or assignments and free to discuss any doubts or concerns. Delegation involves the

acceptance theory of authority. Davis and Newstrom explain this as follows:

Although authority gives people power to act officially within the scope of their delegation, this

power becomes somewhat meaningless unless those affected accept it and respond to it. In most

cases when delegation is made, a subordinate is left free to choose a response within a certain

range of behaviour. But even when an employee is told to perform one certain act, the employee

still has the choice of doing it or not doing it and taking the consequences. It is, therefore, the

subordinate who controls the response to authority. Managers cannot afford to overlook this

human fact when they use authority.

71

When subordinates have agreed and accepted the delegation, they should be properly

briefed, given guidance and support and any necessary training. They should be

advised where, and to whom, they could go for further advice or help. The manager

should make clear to other staff the nature and extent of delegation, and obtain their

co-operation. Where the delegation is likely to involve contact or consultation with

people in other departments or sections or requests for information, the manager

should also communicate with other managers and seek their consent and support.

The simple process of smoothing the pattern of communications should ordinarily

require little effort by the manager. Not only is it a courtesy but also it can do much to

enlist the co-operation of other staff and help avoid any possible misunderstandings.

The manager should agree time limits for delegation (such as a target date for comple-

tion of a specific task or a specified time period). It is necessary to agree the level and

nature of supervision, and to establish a system to monitor progress and provide feed-

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

855

Figure 21.6 Main stages in the process of delegation

Guidance,

support and

training

Monitoring

and review

procedures

856

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Zone of

INSTRUCTION

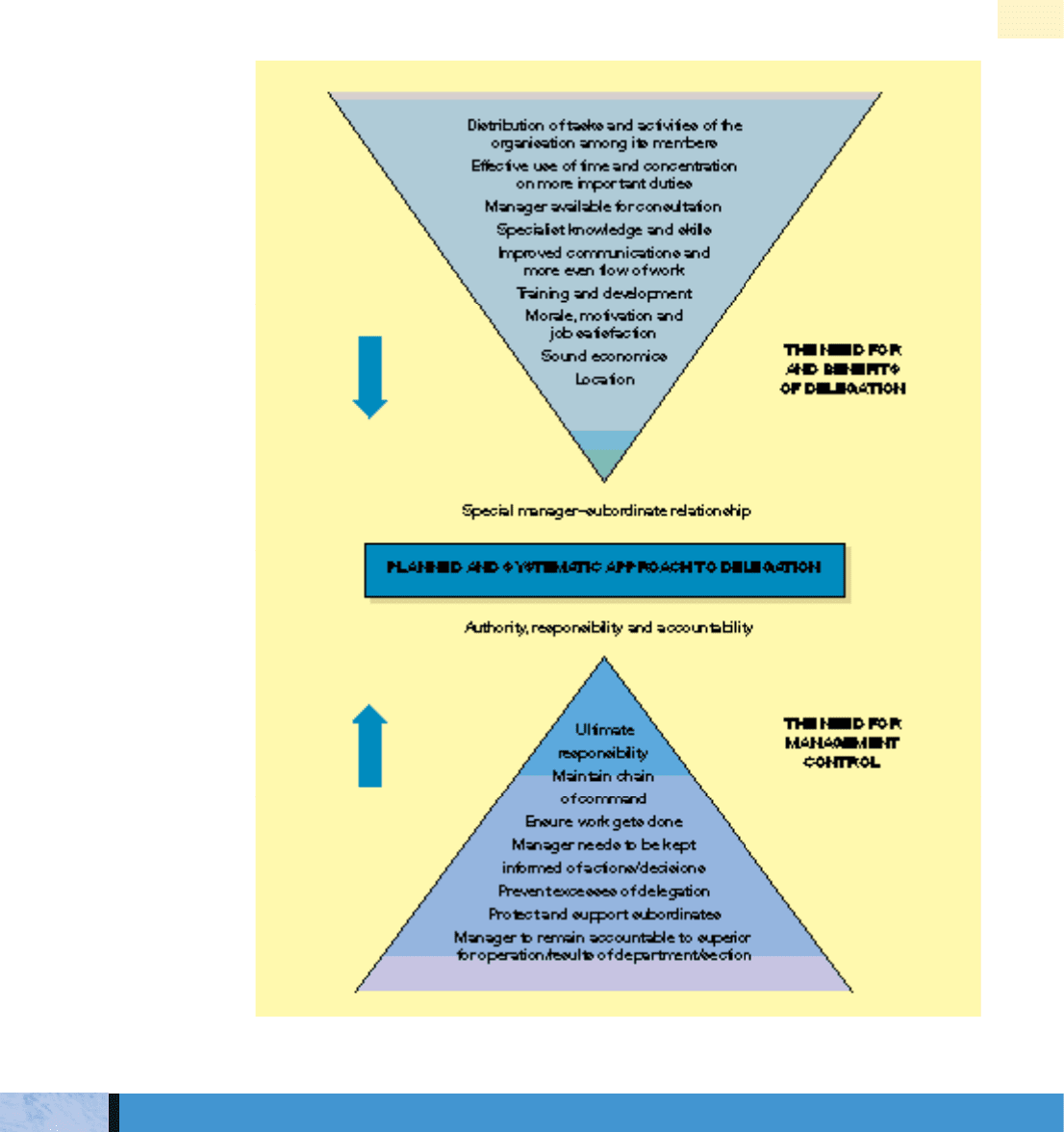

DELEGATION, AUTHORITY, POWER & RESPONSIBILITY

• DELEGATION

• AUTHORITY

• POWER

• RESPONSIBILTY

AUTHORITY

The RIGHT to authority

• Given to the subordinate to do the manager’s job

(otherwise formal organisations cannot exist)

• Extent of delegated authority

Anything the manager has the right to do

(except where the manager is specifically prohibited from doing)

• Cannot totally delegate authority of performing the managerial

functions viz: planning

organising

motivating

communicating

controlling

POWER

The ABILITY to influence another

measured in terms of:

• giving rewards

• promising rewards

• threat to withdraw current rewards

• withdrawing current rewards

• threat of punishment

• punishing

Influenced by

• Subjective factors – ethical/moral. For example,

how much power should a manager have?

• Extent of power significantly determined by the

person being controlled.

• May be more important what a person thinks the

manager’s power is than what it actually is.

DELEGATION OF AUTHORITY & POWER

Authority & Power relationships

A manager must possess both otherwise

conflict occurs. Subordinates must be

provided with equal authority & power at

all levels of an organisation.

= legitimate power or workable authority

• Managers have the right to require

accounting for the authority delegated

& tasks assigned to a subordinate.

• Subordinates must answer to the

manager concerning the stewardship

of the authority granted to him or her

by the manager.

Zone of

DELEGATION

Zone of

EMPOWERMENT

POWER

Management

loses control

Management

controls every detail

ALL RETAINED

BY MANAGEMENT

NONE RETAINED

BY MANAGEMENT

EFFECTIVE DELEGATION

• Understanding the task

• Identifying the correct

person(s) to perform the

task

• Communicating the task

• Setting & discussing the

objectives for the task

• Monitoring progress

• Evaluation & feedback

RESPONSIBILITY

• The obligation to do something.

• The duty to perform the job or

function in the organisation.

• An individual’s obligation to her-

or himself to perform the task.

• Responsibility cannot be delegated.

• Delegating authority can increase

the manager’s responsibility since

there is additional responsibility

for the subordinate’s task.

BENEFITS OF EFFECTIVE DELEGATION

• Efficient use of manager’s

and subordinates’ time

• Motivation of staff

• Development of staff

• Reducing levels of stress in managers

and subordinates

RESPONSIBILITY & ACCOUNTABILITY

• Accountability – a person is

accountable to higher authorities

• Responsibility is created within a

person when accepting a task &

the appropriate delegation of

authority

Zone of

ANARCHY

• EFFECTIVE DELEGATION

• REASONS FOR INEFFECTIVE DELEGATION

INEFFECTIVE DELEGATION

• Heavy work loads

• Lack of appropriate staff

• Unfamiliarity with the task

• Personal characteristics

• Fear of subordinate doing

undesirable things

• Liking by the manager for

the actual job

of – manager

– subordinate

– staff not trained

– staff not in post

of – manager

– subordinates

DELEGATION

‘Delegation is part of the managerial function

involving some element of risk’

Both the delegator &

the person(s) to whom

the work is delegated

Using appropriate

communication methods

• Verbal/Written/

Diagrammatic

Objectives require

• time scales

• quality of the results

to be quantified

Based on

• Previous performance

• Special skills

• Special circumstances

Figure 21.7 Summary outline of delegation, authority, power and responsibility

(Adapted and reproduced with permission of Training Learning Consultancy Ltd, Bristol.)

back. It is also important to agree response deadlines, check points and specific times

to meet, and the review of performance within the agreed terms of reference: for ex-

ample, to discuss progress with the manager at the end of each week, or to discuss the

first draft of a report before it progresses further, and by an agreed date. Delegation is

not an irrevocable act; it can always be withdrawn. It is also important to make

clear expected levels of achievement and agree on performance standards (wherever

practically possible in quantitative terms), and how performance in each area is to be

measured and evaluated.

The subordinate should then be left alone to get on with the job. One of the most frus-

trating aspects of delegation is the manager who passes on authority but stays close

behind the subordinates’ shoulders keeping a constant watch over their actions. This is

contrary to the nature of delegation. The true nature of successful delegation means

that the subordinate is given freedom of action within the boundaries established

and agreed in the previous stages.

A planned and systematic approach means that effective delegation can be achieved

within the formal structure of the organisation and without loss of control. Modern

methods of management can also assist the effectiveness of delegation. Procedures

such as management by exception and staff appraisal are useful means of helping to

maintain control without inhibiting the growth of delegation. Delegation can be

increased under a system of Management by Objectives which allows staff to accept

greater responsibility and to make a greater personal contribution.

Wherever possible, the process of delegation should be related to some form of associ-

ated ‘reward’ system. Examples could include bonus payments, improved job

satisfaction, reduction of work stress, and enhanced opportunities for promotion or

personal development, including further delegation. A ‘summary outline’ of delega-

tion, authority, power and responsibility is presented in Figure 21.7.

The art of delegation is to agree clear terms of reference with subordinates, to give them

the necessary authority and responsibility and then to monitor their performance with-

out undue interference or the continual checking of their work. Effective delegation is a

social skill. It requires a clear understanding of people-perception, reliance on other

people, confidence and trust, and courage. It is important that the manager chooses the

right subordinates to whom to delegate authority and responsibility. The manager must

know what to delegate, when and to whom. Matters of policy and disciplinary power,

for example, usually rest with the manager and cannot legitimately be delegated.

Delegation is a matter of judgement and involves the question of discretion.

Delegation is also a matter of confidence and trust – both in subordinates and the

manager’s own performance and system of delegation. In allowing freedom of action

to subordinates within agreed terms of reference and the limits of authority, man-

agers must accept that subordinates may undertake delegated activities in a

different manner from themselves. This is at the basis of the true nature of delega-

tion. However, learning to put trust in other people is one of the most difficult aspects

of successful delegation for many managers, and some never learn it.

Delegation is also a matter of courage. If a subordinate comes to a manager with a

problem the manager should insist on a recommendation from the subordinate.

Delegation involves subordinates making decisions. For example, as Guirdham points

out: ‘A strict separation of manager and subordinate roles sends the message to workers

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

857

Freedom of

action

Related reward

‘systems’

Confidence

and trust

Training and

learning

experience

THE ART OF DELEGATION

that they are only responsible for what they are specifically told to do. Managers who

neglect to, or cannot, delegate are failing to develop the human resources for which

they have responsibility.’

72

Mistakes will inevitably occur and the subordinate will need to be supported by the

manager, and protected against unwarranted criticism. The acceptance of ultimate

responsibility highlights the educational aspect of the manager’s job. The manager

should view mistakes as part of the subordinate’s training and learning experience, and

an opportunity for further development. ‘Even if mistakes occur, good managers are

judged as much by their ability to manage them as by their successes.’

73

Notwithstanding any other consideration the extent and nature of delegation will ultimately

be affected by the nature of individual characteristics. The ages, ability, training, attitude,

motivation and character of the subordinates concerned will, in practice, be major determi-

nants of delegation. An example is where a strong and forceful personality overcomes the

lack of formal delegation; or where an inadequate manager is supported by a more compe-

tent subordinate who effectively acts as the manager. Failure to delegate successfully to a

more knowledgeable subordinate may mean that the subordinate emerges as an informal

leader and this could have possible adverse consequences for the manager, and for the

organisation. Another example, and potential difficulty, is when a manager is persuaded to

delegate increased responsibility to persons in a staff relationship who may have little

authority in their own right but are anxious to enhance their power within the organisation.

The need for control

The concept of ultimate responsibility gives rise to the need for effective management

control over the actions and decisions of subordinate staff. Whatever the extent of their

delegated authority and responsibility, subordinates remain accountable to the manager

who should, and hopefully would, wish to be kept informed of their actions and deci-

sions. Subordinates must account to the manager for the discharge of the responsibilities

which they have been given. The manager will therefore need to keep open the lines of

delegation and to have an upward flow of communication. The manager will need to be

kept informed of the relevance and quality of decisions made by subordinates.

The concept of accountability is therefore an important principle of management.

The manager remains accountable to a superior not just for the work carried out per-

sonally but also for the total operation of the department/section. This is essential in

order to maintain effective co-ordination and control, and to maintain the chain of

command. Successful delegation involves ‘letting go without losing control’.

74

Authority, responsibility and accountability must be kept in parity throughout the

organisation. The manager must remain in control. The manager must be on the look-

out for subordinates who are more concerned with personal empire building than with

meeting stated organisational objectives. The manager must prevent a strong personal-

ity exceeding the limits of formal delegation.

We have said that delegation creates a special manager–subordinate relationship.

This involves both the giving of trust and the retention of control.

The essence of the delegation problem lies in the trust–control dilemma. The dilemma is that in

any one managerial situation, the sum of trust + control is always constant. The trust is the trust

that the subordinate feels that the manager has in him. The control is the control that the man-

ager has over the work of the subordinate.

75

Control is, therefore, an integral part of the system of delegation. However, control

should not be so close as to inhibit the effective operation or benefits of delegation. It

is a question of balance. (See Figure 21.8.)

858

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Individual

characteristics

A question

of balance

In Chapter 18, we discussed how getting the best out of people and attempting to

improve job satisfaction demands a spirit of co-operation and allowing people a

greater say in decisions that affect them at work. Managers need to relinquish close

control in favour of greater empowerment of employees. This gives members of staff a

sense of personal power and control over their work and responsibility for making

their own decisions.

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

859

THE CONCEPT OF EMPOWERMENT

Figure 21.8 The balance between delegation and control

Despite the general movement towards less mechanistic structures and the role of

managers as facilitators there appears to be some reluctance especially among top man-

agers to dilute or weaken hierarchical control. A study of major UK businesses suggests

that there are mixed reactions to the new wave of management thinking. While the

prospect of empowerment can hold attractions for the individual employee, many

managers are keen to maintain control over the destiny, roles and responsibilities of

others. Beneath the trappings of the facilitate-and-empower philosophy the command-

and-control system often lives on.

76

However, in a discussion on modern leadership and management, Gretton makes the

point that: ‘ Today’s leaders understand that you have to give up control to get results.

That’s what all the talk of empowerment is about.’

77

As Ellis and Dick point out, all human relationships embody an element of power

and in mature relationships power is allowed to shift between parties in accordance

with who is the most appropriate person to hold power.

In any organizational setting power relations are crucial in determining the way managers and

subordinates work together. When power is held totally in the hands of the manager or owner,

because they have ultimate power to employ or dismiss or they control all the resources that

employees use, the temptation to employ a dictatorial style of management will be strong. At the

other extreme, if employees have organizational power through their ownership of intellectual

skills, information or ability, a more consensual or partnership style of management would be

more appropriate.

78

According to a report from the Chartered Management Institute, younger managers (aged

25–35) positively seek empowerment at work. Along with confidence to take charge of

their own careers, these younger managers also expect a new employer–employee working

relationship, built on partnership and trust. Their preferred management style is one that

empowers, in contrast to the bureaucracy and authoritarianism that still prevails in many

organisations.

79

The meaning of empowerment

Empowerment

is generally explained in terms of allowing employees greater freedom,

autonomy and self-control over their work, and responsibility for decision-making.

However, there are differences in the meaning and interpretation of the term ‘empower-

ment’. Wilkinson refers to problems with the existing prescriptive literature on

empowerment. The term ‘empowerment’ can be seen as flexible and even elastic, and has

been used very loosely by both practitioners and academics. Wilkinson suggests that it is

important to see empowerment in a wider context. It needs to be recognised that it has dif-

ferent forms and should be analysed in the context of broader organisational practice.

80

Perceptions of empowerment also differ depending on your management position.

Companies are failing to match their promises of employee involvement with action and

many companies are only paying lip-service to real involvement.

81

The concept of empowerment also gives rise to the number of questions and doubts.

For example, how does it differ in any meaningful way from other earlier forms of

employee involvement? Is the primary concern of empowerment getting the most out

of the workforce? Is empowerment just another somewhat more fanciful term for dele-

gation? Some writers see the two as quite separate concepts whilst other writers suggest

empowerment is a more proactive form of delegation. Johnson and Redmond view

empowerment as the pinnacle of employee involvement and at the end of a chain in

social participation.

82

According to Mills and Friesen, ‘Empowerment can be succinctly defined as the

authority of subordinates to decide and act’.

860

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

It describes a management style. The term is often confused with delegation but, if strictly

defined, empowerment goes much further in granting subordinates authority to decide and act.

Indeed, within a context of broad limits defined by executives, empowered individuals may even

become self-managing.

83

Managerial initiatives and meanings

By employing and adapting terms used in the wider literature on empowerment,

Lashley suggests it is possible to summarise four managerial initiatives and meanings

which claim to be empowering:

■ empowerment through participation – for example, the delegation of decision-

making which in a traditional organisation would be the domain of management;

■ empowerment through involvement – for example, when management’s concern

is to gain from employees’ experiences, ideas and suggestions;

■ empowerment through commitment – for example, through greater commitment

to the organisation’s goals and through improvement in employees’ job satisfaction;

■ empowerment through de-layering – for example, through reducing the number

of tiers of management in the organisation structure.

Empowerment takes a variety of forms. Managers frequently have different intentions

and organisations differ in the degree of discretion with which they can empower

employees. Lashley concludes therefore that the success of a particular initiative will be

judged by the extent to which the empowered employees feel personally effective, are

able to determine outcomes and have a degree of control over significant aspects of

their working life.

84

A full discussion on the meaning and nature of empowerment is given in

Management in Action 21.1 at the end of this chapter.

True empowerment

Stewart suggests that to support true empowerment there is a need for a new theory of

management – Theory E – which states that managers are more effective as facilitators than

as leaders, and that they must devolve power, not just responsibility, to individuals as well

as groups.

85

Morris, Willcocks and Knasel believe, however, that to empower people is a real

part of leadership as opposed to management and they give examples of the way empower-

ment can actually set people free to do the jobs they are capable of.

86

Both make the point,

however, that true empowerment is much more than conventional delegation.

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

861

The Police Service has statutory responsibility for the

treatment of persons detained by them (and other agen-

cies such as Customs & Excise who bring persons into a

police station). These persons must be treated in accor-

dance with the Police & Criminal Evidence Act 1984

(PACE) which was enacted in January 1986 and any code

of practice issued under the Act (of which there are cur-

rently five, codes A–E with code C specifically relating to

issues of detention).

Section 39 of PACE specifies that these duties should

be the duty of the custody officer at a police station. The

same section goes on to declare where:

a) an officer of higher rank than the custody officer

gives directions ... which are at variance with any

decision or action taken by the custody officer in

the performance of a duty imposed on him under this

Act the matter shall be referred at once to an officer

of the rank of Superintendent or above who is

responsible for that police station.

There is then statutory backing for the decisions and

actions taken by a custody officer in the performance of

his duties.

PACE sets out the provisions regarding the appointment

of custody officers (Section 36). Custody officers are

Empowerment and the custody officer

EXHIBIT 21.1

862

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

appointed to designated police stations, which are effec-

tively police stations equipped to receive and house

detained persons in the conditions that PACE requires.

Subject to limited exceptions all detained persons must go

to a designated police station. Custody officers are

appointed by the Chief Officer of Police for that area or by

an officer directed by that Chief Officer of Police to do so.

Importantly no police officer may be appointed a Custody

Officer unless at least the rank of Sergeant and significantly

none of the functions of a Custody Officer shall be per-

formed by an officer who is involved in the investigation of

an offence for which the person is in detention (and there is

case law that identifies what being involved in an investiga-

tion entails).

Most forces have adopted the Sergeant rank as the best

suited to the custody officer role. Here in Hampshire that is

the case. Sergeants on appointment receive training in the

role of Sergeant and specifically custody officer duties.

They then undertake a process of accreditation as a cus-

tody officer which lasts from three to twelve months.

Custody officers, though they work for the same organisa-

tion, have an element of impartiality through the statement

that they must not be involved in the investigation of an

offence for which that person is detained. This allows for

their decision-making to be non-partisan. There is an argu-

ment perhaps that for the decision-making to be

completely impartial custody provisions should be inde-

pendent of the police service but in practice I would argue

custody officers value their impartiality and their decision-

making is reflected in this.

The Act clearly defines the process for any challenge to

custody officers’ decision-making and that is by appeal to

the station commander, a Superintendent. As well as pro-

viding support for custody officers in their decision-making

it also affords protection for them from rank pulling in a

hierarchically structured organisation such as the police.

PACE separates the decisions to be taken by custody

officers into two areas before and after charge.

Before

A custody officer has to determine whether there is suffi-

cient evidence to charge and may detain a person in order

to do so. If there is not sufficient evidence to charge then

the custody officer should release that person either with or

without bail unless their detention is necessary to preserve

and secure evidence relating to an offence for which they

are under arrest or to obtain such evidence by questioning.

Bail can be conditional, for example imposition of a curfew,

a condition of residence, reporting to a police station. All of

these conditions have to be justified and there is a course

of appeal to magistrates.

After

Custody officers shall order detained persons’ release

either with or without bail after charge unless certain condi-

tions apply.

In addition to authorising the detention of a person

Custody Sergeants can order a strip search and are

responsible for arranging any additional protective meas-

ures for persons who are either juvenile, mentally ill or a

foreign national. The custody officer has responsibility for

the welfare and procedural process of a detainee and must

follow the guidelines of the codes of practice in respect of

provision of meals, blankets, writing materials etc. The cus-

tody officer has no authority to deny (or delay) access to a

solicitor, to deny (or delay) a telephone call or letter or to

delay any notification requested by the detained person.

Any denial (or delay) of rights requires the authorisation of

senior officers.

Custody officers deal with people’s liberty and deter-

mine whether they enter the legal process by charging

them to appear at court. This is serious business and in

practical terms it is taken very seriously. Their decision-

making in this process is subject to periodic review. In the

first 24 hours of a person’s detention that review is under-

taken at the six, 15 and 24 hour stage. Any detention

beyond 24 hours requires the authority of a Superintendent

and any detention beyond 36 hours requires a warrant

from a Court. The custody officer’s decision-making is

subject to close scrutiny through the training process,

accreditation process and local inspection processes. Most

importantly it is a legal requirement now that all designated

custody centres are videotaped, which is perhaps the ulti-

mate scrutiny. The arrival of video recording tapes in

custody centres was welcomed by custody officers as it

saw a corresponding fall in the number of complaints

against them in the charge room process.

In practical terms having worked with PACE since 1986

I have only encountered one decision of a custody officer

which was challenged by a more senior officer (a Detective

Chief Inspector). This challenge related to a decision by

Exhibit 21.1 continued

Photo: Gusto/Science Photo Library

In previous chapters we have discussed the changing nature of the work environment

and emphasised the requirement for management to harness and develop the talents

and commitment of all employees. Effectively managed, delegation and empowerment

can offer a number of potential benefits throughout all levels of the organisation. But

does empowerment promote greater motivation and increase job satisfaction and work

performance? Does empowerment deliver?

From a study of 171 employees in a major Canadian life insurance company,

Thorlakson and Murray found no clear evidence for the predicted effects of empower-

ment. However, they suggest that the potential effectiveness of empowerment should

not be ruled out. The larger the organisation, the more difficult to institute participa-

tory management. In this study, the participants were members of a large organisation

and corporate size, together with the top-down implementation of empowerment,

could have played a major role.

87

Peiperi poses the question, ‘Does empowerment deliver the goods?’ and concludes:

Empowerment says that employees at all levels of an organization are responsible for their own

actions and should be given authority to make decisions about their work. Its popularity has

been driven by the need to respond quickly to customer needs, to develop cross-functional links

to take advantage of opportunities that are too local or too fleeting to be determined centrally.

Better morale and compensation for limited career paths are other advantages. Potential difficul-

ties include the scope for chaos and conflict, a lack of clarity about where responsibility lies, the

breakdown of hierarchical control, and demoralization on the part of those who do not want addi-

tional authority. Successful empowerment will typically require feedback on performance from a

variety of sources, rewards with some group component, an environment which is tolerant of

mistakes, widely distributed information, and generalist managers and employees. The paradox

is that the greater the need for empowerment in an organization, the less likelihood of success. It

has to be allowed to develop over time through the beliefs/attitudes of participants.

88

According to Erstad, among the many fashionable management terms, empowerment

refers to a change strategy with the objective of improving both the individual’s and

the organisation’s ability to act. In the service sector, for example, empowerment is

often seen as a way to gain competitive advantage but the true potential is broader.

From the context of articles specialising in this area, Erstad concludes that empower-

ment is a complex process. In order to be successful it requires a clear vision, a learning

environment both for management and employees, and participation and implemen-

tation tools and techniques.

89

Potential benefits

Nixon suggests that by empowering staff right through the organisation structure, every

employee will have the power to be innovative and ensure performance is good.

Conflict will be abolished as everyone works towards the same goals and training will

CHAPTER 21 ORGANISATIONAL CONTROL AND POWER

863

the custody officer to release a person charged with

burglary on bail. The senior investigating officer wanted

bail refused. The matter was accordingly referred to the

local Superintendent. The fact that these occasions are

so rarely reported is evidence of the seriousness and pro-

fessionalism adopted by Custody Sergeants in their

decision-making process. A process that would only work

with empowerment.

(I am grateful to Inspector Derek Stubbington of The Hampshire Constabulary

for providing this information.)

DOES EMPOWERMENT DELIVER?

increase learning.

90

Green believes that employees should thrive given the additional

responsibility from empowerment:

An empowered employee is thus given more ‘space’ to use his or her talents, thereby facilitating

much more decision-making closer to the point of impact. Empowering employees gives the fol-

lowing additional advantages:

■ The decision-making process can be speeded up, as can reaction times.

■ It releases the creative innovative capacities.

■ Empowerment provides for greater job satisfaction, motivation and commitment.

■ It enables employees to gain a greater sense of achievement from their work and reduces

operational costs by eliminating unnecessary layers of management and the consequent

checking and re-checking operations.

91

Empowerment makes greater use of the knowledge, skills and abilities of the workforce;

it encourages teamworking; and if there is meaningful participation, it can aid the suc-

cessful implementation of change programmes.

92

Wall and Wood suggest that although

few manufacturing companies empower their staff, research shows that empowerment

can be one of the most effective tools in raising both productivity and profit.

Empowerment improves performance because of the opportunities empowerment pro-

vides for them to do their work more effectively. It develops an individual’s knowledge so

they take a broader and more proactive orientation towards their job, are more willing to

suggest new ways of doing things and to engage in meaningful teamworking.

93

Findings

from a Whitehall II study of over 10000 civil servants on work-related stress suggests that

giving people more control over their jobs can greatly benefit their health.

94

We should also remember the potential positive outcomes of empowerment and its

importance as part of a programme of total quality management (discussed in Chapter 23).

Whatever the form or nature of the control system, or the extent of delegation or

empowerment, an essential feature underlying its success is the need to consider the

behavioural implications.

The broad objective of the control function is to effectively employ all the resources committed to an

organization’s operations. However, the fact that non-human resources depend on human effort for

their utilization makes control, in the final analysis, the regulation of human performance.

95

Control often provokes an emotional response from those affected by it. It should be

recognised, therefore, that the activities of a management control system raise impor-

tant considerations of the human factor and of the management of people. The

effectiveness of management control systems will depend upon both their design and

operation, and the attitudes of staff and the way they respond to them. The manner in

which control is exercised and the perception of staff will have a significant effect on

the level of organisational performance.

96

Whatever the extent of employee empowerment there is still a requirement for some

form of management control, and this gives rise to a number of important behavioural

considerations. We have seen that control systems can help fulfil people’s needs at

work and their presence may be welcomed by some members of staff. Often, however,

control systems are perceived as a threat to the need satisfaction of the individual.

Control over behaviour is resented and there is a dislike of those responsible for the

operation of the control system. Control systems provide an interface between

human behaviour and the process of management. Even when control systems are

well designed and operated there is often strong resistance, and attempts at non-

compliance, from those affected by them.

864

PART 8 IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

BEHAVIOURAL FACTORS IN CONTROL SYSTEMS

Resistance to

control

systems