Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

69

II. PRIMARY COMPLAINTS

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA

CHAPTER 10

Kenneth C. Jackimczyk, MD, FACEP

1. What is coma? What terms should be used to describe altered

sensorium?

A depressed mental state in which verbal and physical stimuli cannot elicit useful

responses. Other terms, such as lethargic, stuporous, or obtunded, mean different things

to different observers and should be avoided. You may be alert but confused as you read

this chapter. It is best to describe the mental functions the patient can perform (e.g., the

patient is oriented to person, place, and time; and can count backward from 10).

2. What causes coma?

Mental alertness is maintained by the cerebral hemispheres in conjunction with the

reticular activating system. Coma can be produced by diffuse disease of both cerebral

hemispheres (usually a metabolic problem), disease in the brain stem that damages the

reticular activating system, or a structural central nervous system (CNS) lesion that

compresses the reticular activating system. Less than 20% of patients have a structural

cause for their coma.

3. How can I remember the causes of coma and altered mental status?

TIPS and vowels, that is, TIPS and AEIOU.

TIPS

T, Trauma, temperature

I, Infection (CNS and systemic)

P, Psychiatric

S, Space-occupying lesions, stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, shock

VOWELS

A, Alcohol and other drugs

E, Epilepsy, electrolytes, encephalopathy

I, Insulin (diabetes)

O, Oxygen (lack of), opiates

U, Uremia

4. What important historical facts should be obtained from the patient with

altered mental status or coma?

This seems like a stupid question because the patient with altered consciousness cannot

give you a reliable history, and the comatose patient cannot give any history at all! You

should carefully question prehospital personnel and attempt to contact the patient’s

friends or family. Ask about the onset of symptoms (acute or gradual), recent neurologic

symptoms (e.g., headache, seizure, or focal neurologic abnormalities), drug or alcohol

abuse, recent trauma, prior psychiatric problems, and past medical history (e.g.,

neurologic disorders, diabetes, renal failure, cancer, or liver failure). If you are having

trouble getting historical information, search the patient’s belongings for pill bottles,

check the patient’s wallet for telephone numbers or names of friends, and review

previous medical records.

Chapter 10 ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA70

5. How can I perform a brief, directed physical examination on a patient with

altered consciousness?

The goal of the physical examination is to differentiate structural focal CNS problems from

diffuse metabolic processes. Pay special attention to vital signs, general appearance, mental

status, eye findings, and the motor examination. Vital signs and eye findings are discussed

elsewhere in this chapter.

The general appearance should be noted before examining the patient. Are there signs of

trauma? Is there symmetry of spontaneous movements?

Motor examination is done to determine the symmetry of motor tone or strength and

response of deep tendon reflexes.

6. How do I evaluate the patient’s mental status?

Mental status can be assessed quickly. Ask four sets of progressively more difficult questions:

a. Orientation to person, place, and time.

b. Count backward from 10 (if done correctly, ask for serial 3s or 7s).

c. Recent recall of three unrelated objects.

7. What is the Glasgow Coma Scale?

A simple scoring system used in trauma patients to define the level of consciousness. It is

useful for standardizing assessments among multiple observers and for monitoring changes

in the degree of coma. The score is determined by eliciting the best response obtained from

the patient in three categories (see Table 10-1). It is not sensitive enough to detect subtle

alterations of consciousness in the noncomatose patient.

TABLE 10-1. GLASGOW COMA SCALE

Observation Points

Eye opening Spontaneous 4

To verbal command 3

To pain 2

No response 1

Best verbal response Oriented or converses 5

Confused conversation 4

Inappropriate words 3

Incomprehensible sounds 2

No response 1

Best motor response Obeys 6

Localizes pain 5

Flexion withdrawal 4

Decorticate posture 3

Decerebrate posture 2

No response 1

Total points 3–15

Chapter 10 ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA 71

8. How important is measuring the temperature of the comatose patient?

Vital signs often provide clues to the cause of coma. A core temperature must be obtained. An

elevated temperature should lead you to investigate the possibility of meningitis, sepsis, heat

stroke, or hyperthyroidism. Hypothermia can result from environmental exposure,

hypoglycemia, or, rarely, addisonian crisis. Do not assume that an abnormal temperature has

a neurogenic cause until you eliminate other causes.

9. What is the significance of other vital signs?

n

Check the cardiac monitor. Bradycardia or arrhythmias can alter cerebral perfusion and

cause altered sensorium.

n

Carefully count respirations. Tachypnea may indicate the presence of hypoxemia or a

metabolic acidosis, and diminished respiratory efforts may require assisted ventilation.

n

Check the blood pressure. Do not assume that hypotension has a CNS cause. Look for

hypovolemia or sepsis as a cause for hypotension. Hypertension may be a result of

increased intracranial pressure, but uncontrolled hypertension also may cause

encephalopathy and coma.

n

Do not forget to obtain the fifth vital sign—measurement of oxygen saturation.

10. What is Cushing’s reflex?

An alteration of vital signs—increased blood pressure and decreased pulse—secondary to

increased intracranial pressure.

11. Define decorticate and decerebrate posturing.

Posturing may be seen with noxious stimulation in a comatose patient with severe brain

injury.

n

Decorticate posturing is hyperextension of the legs with flexion of the arms at the elbows.

Decorticate posturing results from damage to the descending motor pathways above the

central midbrain.

n

Decerebrate posturing is hyperextension of the upper and lower extremities; this is a

graver sign. Decerebrate posturing reflects damage to the midbrain and upper pons. If you

have trouble remembering which position is which, think of the upper extremities in flexion

with the hands over the heart (cor) in de-cor-ticate posturing.

12. What information can be obtained from the eye examination of the comatose

patient?

The eyes should be examined for position, reactivity, and reflexes. When the eyelids are

opened, note the position of the eyes. If the eyes flutter upward, exposing only the sclera,

suspect psychogenic coma. If the eyes exhibit bilateral roving movements that cross the

midline, you know that the brain stem is intact. Pupil reactivity is the best test to differentiate

metabolic coma from coma caused by a structural lesion because it is relatively resistant to

metabolic insult and usually is preserved in a metabolic coma. Pupil reactivity may be subtle,

necessitating use of a bright light in a dark room.

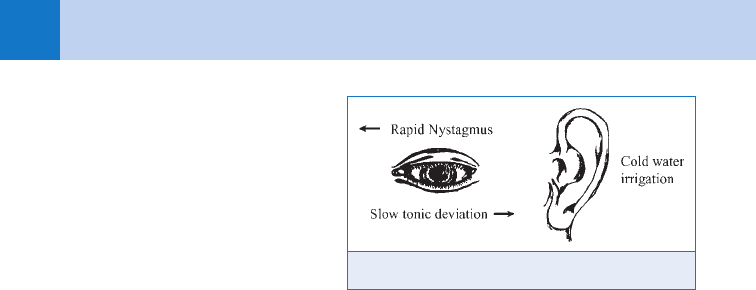

13. How do I test the eye reflexes?

Testing of the eye reflexes is the best method for determining the status of the brain stem.

Two methods can be used:

a. Oculocephalic (doll’s eyes)

Oculocephalic testing requires rapid twisting of the neck, which is a bad idea in the

unconscious patient because occult cervical spine trauma may be present.

b. Oculovestibular (cold calorics)

Oculovestibular testing is easy to do and can be done without manipulating the neck. The

ear canal is irrigated with 50 mL of ice water. A normal awake patient has two competing eye

movements: rapid nystagmus away from the irrigated ear and slow tonic deviation toward the

cold stimulus. Remember the mnemonic COWS (Cold Opposite, Warm Same), which refers to

the direction of the fast component. (See Fig. 10-1.)

Chapter 10 ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA72

14. How do I interpret the eye

reflexes?

A patient with psychogenic coma

has normal reflexes and exhibits

rapid nystagmus. A comatose

patient with an intact brain stem

lacks the nystagmus phase, and the

eyes deviate slowly toward the

irrigated ear. If the eyes do

anything else (usually not a good

sign), refer to a neurology text to

determine the exact location of the

lesion.

15. I want to impress the attending physicians. Do you have any tips on physical

examination that will let me assume my rightful position as star student?

n

If a confused patient is suspected of being postictal, look in the mouth. A tongue laceration

supports the diagnosis of a seizure.

n

Put on gloves and inspect the scalp. Occult trauma is often overlooked, and you may find a

laceration or dried blood. An old scar on the scalp may tip you off to a posttraumatic

seizure disorder.

n

Do not be fooled by a positive blink test in a patient with suspected psychogenic coma.

When you rapidly flick your hand at a comatose patient who has open eyes, air movement

may stimulate a corneal reflex in a patient who is truly comatose.

n

Do not be misled by the odor of alcohol. Alcohol has almost no detectable odor, which is

why alcoholics drink vodka at work. Other spirited liquors such as brandy have a strong

odor. The comatose executive who smells drunk may have had a sudden subarachnoid

hemorrhage and spilled brandy on his or her shirt.

16. Which plain radiographs should be obtained in the comatose patient?

A cervical spine series (or cervical spine computed tomography [CT]) should be obtained in any

comatose patient with suspected trauma because physical examination is unreliable. A chest

radiograph may be helpful if hypoxemia, pulmonary infection, or aspiration is suspected.

17. Which diagnostic tests should be obtained in the patient with a significantly

altered level of consciousness?

Obtain a rapid blood glucose, and correct hypoglycemia if it is found. Pulse oximetry should

be obtained on all patients. If alcohol intoxication is suspected, determine the alcohol level

with either a Breathalyzer or serum blood alcohol. If the pupils are constricted or if narcotic

ingestion is suspected, intravenous naloxone should be given. If hypoglycemia or alcohol

intoxication is not found to be the cause of the patient’s confusion, further tests are warranted.

A complete blood count, electrolytes, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and glucose should be

obtained. Toxicologic screens may be done in a patient with a suspected ingestion, but they

are expensive and do not detect routinely every possible ingested substance. Liver function

tests, ammonia level, calcium level, carboxyhemoglobin level, and thyroid function studies

may be helpful in selected patients.

18. When should I order a CT scan?

Although CT scans have revolutionized the practice of medicine, they are not indicated in

every comatose patient. A good history, physical examination, and a few simple laboratory

tests are adequate in many cases seen in the ED because drug and alcohol abuse are

common. If a structural lesion is suspected (e.g., focal neurologic finding, head trauma,

history of cancer), a noncontrast-enhanced CT scan should be ordered immediately. If the

condition of a patient with a suspected metabolic coma worsens or does not improve after a

brief period of observation, a CT scan should be obtained.

Figure 10-1. Testing of eye reflexes.

Chapter 10 ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA 73

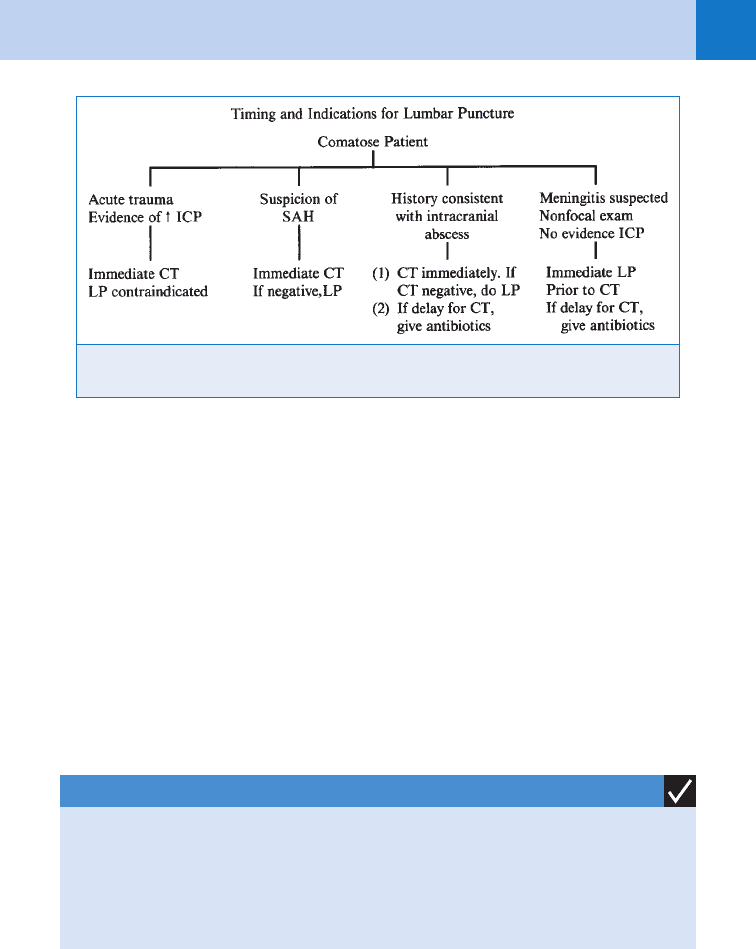

19. When should a lumbar puncture (LP) be done?

The indications and timing of LP depend on two questions:

a. Is CNS infection suspected?

b. Is there a suspicion of a structural lesion causing increased intracranial pressure?

(See Fig. 10-2.)

20. Okay. I have made the diagnosis of coma. What are my initial treatment

priorities?

Emergency medicine requires simultaneous assessment and treatment. A brilliant diagnosis is

useless in a dead patient. Start with the ABCs: airway, breathing, circulation and cervical

spine. Intubate patients with apnea or labored respirations, patients who are likely to aspirate,

and any patient who is thought to have increased intracranial pressure. Maintain cervical spine

precautions until the possibility of trauma has been excluded. Hypotension should be

corrected so that cerebral perfusion pressure is maintained.

KEY POINTS: ALTERE D MENTAL STATUS AND COMA

1. Goal of physical examination is to differentiate structural from metabolic cause.

2. Focus on vital signs, mental status, and motor examination.

3. Check a rapid blood glucose on every comatose patient.

4. Immediately intubate the comatose patient if increased intracranial pressure is suspected.

21. I’ve addressed the ABCs. What do I do next?

Check a rapid blood glucose; if the glucose is low, treat hypoglycemia with D50W. It is better

to do a rapid blood glucose determination rather than to give glucose empirically. Next, give

100 mg of thiamine, and if opioid use is suspected, give 2 mg of naloxone intravenously.

Empirical administration of flumazenil (benzodiazepine antagonist) or physostigmine (reverses

anticholinergic agents) is not routinely indicated in comatose patients. Antibiotic

administration is considered in all febrile patients with coma of unknown origin. A comatose

patient with increased intracranial pressure should be intubated and mechanically ventilated.

Mannitol, 0.5 to 1 gm/kg intravenously, should be considered.

Figure 10-2. Timing and indications for lumbar puncture. CT, computed tomography; ICP,

intracranial pressure; LP, lumbar puncture; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Chapter 10 ALTERED MENTAL STATUS AND COMA74

22. I think my patient is faking it. How can I tell if this is psychogenic coma?

First, be grateful. A patient in psychogenic coma is better than one who is angry and

combative. Approach the patient incorrectly, and you can awaken the patient to a hostile alert

state.

n

Do a careful neurologic examination. Open the eyelids. If the eyes deviate upward and only

the sclera show (Bell’s phenomenon), you should suspect psychogenic coma. When the

eyelids are opened in a patient with true coma, the lids close slowly and incompletely. It is

difficult to fake this movement.

n

Lift the arm and drop it toward the face; if the face is avoided, this is most likely

psychogenic coma. If this does not work, you may want to check some simple laboratory

tests, including a Dextrostix.

n

If the patient remains comatose, irritating but nonpainful stimuli, such as tickling the feet

with a cotton swab, may elicit a response. Remember that this is not a test of wills between

you and the patient. There is no indication for repetitive painful stimulation because it can

make the patient angry and ruin attempts at therapeutic intervention.

n

If all else fails, perform cold caloric testing. The presence of nystagmus confirms the

diagnosis of psychogenic coma. What do you do then? It is time to pick up a copy of

Psychiatry Secrets.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Edlow JA, Caplan LR: Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 342:29–36,

2000.

2. Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR: The poisoned patient with altered consciousness: controversies in the use of a

coma cocktail. JAMA 274:562–569, 1995.

3. Huff JS: Altered mental status and coma. In Tintinalli JE, Kelen JD, Stapczynski JS,editors): Emergency

medicine: a comprehensive study guide, ed 6, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill, pp 1390–1397.

4. Cooke JL. Depressed consciousness and coma . In Marx J, editor: Emergency medicine: concepts and clinical

practice, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Mosby, pp 106-112.

75

FEVER

CHAPTER 11

Diane M. Birnbaumer, MD, FACEP, and Sarah M. Battistich, MD

1. What temperature constitutes a fever?

A temperature of 38°C (100.4°F) in infants or 38.3°C (100.9°F) in adults defines a fever.

However, immunocompromised or functionally immunocompromised patients may

not be able to mount a temperature high enough to constitute a fever by this definition.

In these patients low-grade temperature elevations should be addressed cautiously.

Examples of patients in which the clinician should maintain a high index of suspicion for

masked fever include the elderly, diabetics, intravenous drug users, chronic alcoholics,

people with HIV/AIDS, people on chronic steroids or immune-modulating drugs, and

neutropenic patients.

2. Are all methods of measuring temperature equivalent?

Rectal temperatures are the most accurate representation of core body temperature and

are, therefore, considered the gold standard. Oral, axillary, and tympanic temperature

measurements lack sensitivity, and thus a lack of fever when measured by these

methods does not rule out a fever. In addition, there is no reliable correction factor for

these alternate modalities. When an accurate temperature measurement is crucial to the

patient’s care, a rectal temperature measurement is necessary.

3. How does the body create fever?

Core body temperature is controlled by the anterior hypothalamus. A fever is caused by

elevation of the hypothalamic set point. The body responds by attempting to generate heat

(e.g., by shivering or by increasing the basal metabolic rate) to elevate core temperature.

4. What is the difference between a fever and hyperthermia?

In contrast to fever, hyperthermia results in an elevated temperature without alteration of

the hypothalamic set point. In cases of hyperthermia, the body attempts to cool itself to

achieve a normal temperature, primarily by increasing sweating. A temperature of 41.5°C

(106.7°F) or greater usually represents hyperthermia and not a true fever, especially in

adults. Some examples of hyperthermia include heat stroke, thyroid storm, burns, and

toxidromes, such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serotonin syndrome, and

malignant hyperthermia.

5. How do I address a patient with a subjective fever at home who is afebrile

in the ED?

This situation is mostly commonly encountered in pediatrics. Mothers are accurate in

assessing the presence or absence of a fever 50% to 80% of the time, and they seem to

be more accurate at detecting when the child is febrile than they are at determining that the

child is afebrile. Most experts feel that palpable fevers reported by mothers are probably

real and need to be taken seriously. Additionally, the practice of attributing fevers to

bundling has been disproved; bundling does not alter core body temperatures in infants.

6. Does the degree of fever indicate the severity of the illness?

In general, no. There is no degree of fever that has been clearly associated with a

specific risk of serious infection in patients. The exception to this may be in

nonimmunized children; prior to the widespread use of the Haemophilus influenzae

Chapter 11 FEVER76

vaccine, temperatures over 41.1°C (105.98°F) were associated with a higher incidence of

serious bacterial illness in children. Prior to the approval of the pneumococcal conjugate

vaccine in 2000, occult pneumococcal bacteremia was observed to be three times (10% vs.

3%, respectively) more likely in children with a fever of 39.5°C (103.1°F) or greater versus a

fever of 39.0°C (102.2°F) or greater.

7. What is the best way to reduce a fever?

Most physicians use antipyretics for patients who are uncomfortable because of fever. Within

the range of 40°C to 42°C, there is no evidence that fever is injurious to tissue. Use of

antipyretics should be considered in pregnant women and patients with preexisting cardiac

compromise who would not tolerate the increased metabolic demands of a fever.

Acetaminophen is the antipyretic of choice in most hospitals. Ibuprofen, other nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), and aspirin are also effective. However, due to the

association with Reye’s syndrome, aspirin is usually not recommended for children. Response

to these agents is seen with both serious and benign causes of fever. Recurrence of fever after

antipyretics wear off is often concerning for parents, but it does not distinguish between

serious and benign causes of fever, and parents should be encouraged to base their concerns

on the child’s behavior rather than the height of the fever or its response to antipyretics.

Complementary methods, such as cool bathing and undressing the patient, are generally not

felt to be effective at significantly lowering core body temperature and should be reserved as

adjuncts for higher temperatures. If the temperature is above 41.5°C (106.7°F), the diagnosis

of hyperthermia should be considered and rapid cooling measures used if any concern about

this condition exists. (See Chapter 58.)

8. What are the causes of fever?

First and foremost, at the top of the list is infection (both bacterial and viral). Infection causes

the vast majority of fevers, but other causes must also be included in the differential

diagnosis:

n

Neoplastic diseases (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, or solid tumors)

n

Collagen vascular diseases (e.g., giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus

erythematosus, or rheumatoid arthritis)

n

Central nervous system lesions (e.g., stroke, intracranial bleed, or trauma)

n

Illicit drug use (cocaine, ecstasy [MDMA], or methamphetamines)

n

Withdrawal syndromes (delirium tremens or benzodiazepine withdrawal)

n

Factitious fever

n

Medications

9. Which medications can cause fevers?

Any drug is capable of producing a drug fever; however, the most common culprits are

penicillin and penicillin analogs (see Table 11-1). The fever usually begins 7 to 10 days after

initiation of drug therapy. There is an associated rash or eosinophilia in about 20% of cases.

Drug fever should always be a diagnosis of exclusion.

10. What are some key elements of the history and physical in patients with

fever?

Pay particular attention to associated symptoms (e.g., cough, dysuria, diarrhea, or headache),

duration of fever, ill contacts, history or risk of immunocompromise, and past medical history,

particularly comorbid illnesses. In the physical examination, note the general appearance of

the patient, paying particular attention to subtleties, such as mild mental status changes or

rashes that might be indicative of more serious systemic diseases. In addition to a thorough

routine physical examination, in appropriate cases a more detailed examination of the patient

should be done to look for occult sites of infection, such as the nose/sinuses, rectum (i.e.,

prostatitis, perirectal abscess), and pelvic examination (i.e., pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-

ovarian abscess).

Chapter 11 FEVER 77

11. What is the relationship between fever and tachycardia?

The pulse should increase about 10 beats per minute for each 0.6°C (1°F) increase in

temperature. A pulse-temperature dissociation occurs when the patient has a fever but a heart

rate that is lower than would be expected for the degree of fever. This dissociation occurs in

typhoid, malaria, Legionnaires’ disease, and mycoplasma. In early septic shock, tachycardia

that is inappropriate for the degree of fever is often seen. Tachypnea out of proportion to fever

is characteristic of pneumonia and gram-negative bacteremia. Hypotension, particularly paired

with tachycardia, raises the concern of sepsis.

12. Do all septic patients have a fever?

No, in fact, remember that within the definition of systemic inflammatory response syndrome

(SIRS) is temperature greater than 38°C (100.4°F) or less than 36°C (96.8°F). Not all fevers

are caused by infection, and not all infected patients have a fever.

13. Should everyone with a fever get antibiotics?

Absolutely not. Antibiotic use should be based on the patient’s specific presentation and

diagnosis after an appropriate history and physical examination and directed laboratory and

ancillary tests. Most clinicians advocate giving antibiotics immediately to any patient who

appears toxic or has suspected bacterial meningitis, without delaying for results of ancillary

test or culture results. Other patients who should be considered for early antibiotics are

immunocompromised patients and elderly patients.

14. What is a neutropenic fever, and what is the appropriate workup?

In patients with neutropenia (an absolute neutrophil count below 1,000 per square mm), a

single temperature above 38.3°C (100.9°F) is considered a fever, and fever in these patients is

secondary to infection until proven otherwise. The risk of severe sepsis and septicemia is

higher in these patients, and this initial workup should include screening for all sources of

infection with history and physical. Initial studies should include, at a minimum, a cell count

and differential, metabolic panel, blood cultures, chest radiograph, and urinalysis; other

studies should be ordered as indicated. All these patients should receive antibiotics, and most

are admitted to the hospital.

Antibiotics

Isoniazid (INH)

Nitrofurantoin

Penicillins, cephalosporins

Rifampin

Sulfonamides

Anticancer drugs

Bleomycin

Streptozocin

Cardiac drugs

Hydralazine

Methyldopa

Nifedipine

Phenytoin

Procainamide

Quinidine

Anticonvulsants

Phenytoin

Carbamazepine

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Ibuprofen

Salicylates

Others

Barbiturates

Cimetidine

Iodides

TABLE 11-1. DRUGS COMMONLY ASSOCIATED WITH DRUG FEVERS