Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 13 ABDOMINAL PAIN88

5. What is the relationship of peritoneal inflammation to loss of appetite?

Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are directly proportional to the severity and extent of

peritoneal irritation. The presence of appetite does not rule out a surgically significant

inflammatory process, such as appendicitis. A retrocecal appendicitis with limited peritoneal

irritation may be associated with minimal gastrointestinal (GI) upset, and one third of all

patients with acute appendicitis do not report anorexia on initial presentation.

6. Discuss the pitfalls in evaluating elderly patients with acute abdominal pain.

Advanced age may and often does blunt the manifestations of acute abdominal disease. Pain

may be less severe; fever often is less pronounced, and signs of peritoneal inflammation, such

as muscular guarding and rebound tenderness, may be diminished or absent. Elevation of the

white blood cell (WBC) count is also less sensitive. Cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction, and

appendicitis are the most common causes for acute surgical abdomen in the elderly. Because

of atypical clinical presentations, additional screening tests, such as amylase, liver function

studies, and alkaline phosphatase, and the liberal use of ultrasound or computed tomography

(CT) scan may be useful in this age group.

7. What other factors should be sought in the history that may alter significantly

the presentation of patients with abdominal pain?

Symptoms and physical findings in patients with schizophrenia and diabetes may be muted

significantly. The prior use of steroids or antibiotics may alter signs and laboratory results

substantially.

KEY POINTS: APPENDICITIS

1. The most sensitive findings are right lower quadrant tenderness, nausea, and anorexia.

2. Clinical scoring systems are useful for risk stratification but not for excluding the diagnosis.

3. Ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are most useful in equivocal cases

or patient groups with multiple possible alternative diagnoses.

8. What is the significance of obstipation?

Obstipation is the inability to pass either stool or flatus for more than 8 hours despite a

perceived need, and is highly suggestive of intestinal obstruction.

9. What vital sign is associated most closely with the degree of peritonitis?

Tachycardia is virtually universal with advancing peritonitis. The initial pulse is less important

than serial observations. An unexplained rise in pulse may be an early clue that early surgical

exploration is indicated. However, this response may be blunted or absent in elderly patients.

10. Does the duration of abdominal pain help in categorizing cause?

Severe abdominal pain persisting for 6 or more hours is likely to be caused by surgically

correctable problems. Patients with pain of more than 48 hours’ duration have a significantly

lower incidence of surgical disease than do patients with pain of shorter duration.

11. Name the two most commonly missed surgical causes of abdominal pain.

Appendicitis and acute intestinal obstruction.

12. Is there a place for narcotic analgesics in the management of acute abdominal

pain of uncertain cause?

For fear of masking vital symptoms or physical findings, old, conventional surgical wisdom

proscribes the use of narcotic analgesics until a firm diagnosis is established. Increasingly,

Chapter 13 ABDOMINAL PAIN 89

however, studies have demonstrated that pain medication may be given to selected patients

with stable vital signs because the analgesic effect may be reversed readily at any time by the

administration of naloxone. In a review article, Ranji et al found that pain control with opiates

may alter the physical examination findings, but these changes result in no significant increase

in management errors. Although inconclusive, a growing body of data suggests that evaluation

of acute abdominal disease may be facilitated when severe pain has been controlled and the

patient can cooperate more fully.

13. Which are the most useful preliminary laboratory tests to order?

A complete blood count with differential and urinalysis are generally recommended. The

initial hematocrit helps to define antecedent anemia. An elevated WBC count suggests

significant pathology but is nonspecific. Elevated urinary specific gravity reflects

dehydration, and an increased urinary bilirubin in the absence of urobilinogen points

toward total obstruction of the common bile duct. Pyuria, hematuria, and a positive

dipstick for glucose and ketones may reveal nonsurgical causes for abdominal pain. For

patients with epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, lipase and liver function studies are

advised. Any woman with childbearing capability should receive a pregnancy test. Serum

electrolytes, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine are indicated if there is clinical

dehydration or other reason to suspect abnormality such as renal failure, diabetes, or a

metabolic acidosis.

14. Are plain radiographs always indicated?

No. Plain films of the abdomen have the highest yield when used in the evaluation of patients

with suspected bowel obstruction, intussusception, ileus, and free air secondary to a

perforated viscus. They have much less utility in detecting intra-abdominal mass, renal calculi,

diverticulitis, gallbladder disease, and abdominal aortic aneurysms. If these disorders are

suspected, other studies such as ultrasound or abdominal CT are more appropriate.

Conversely, among patients with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease or massive hematemesis,

pain present for more than 1 week, strangulated abdominal wall hernias, or other obvious

clinical indications for laparotomy, plain radiographs add little.

15. Which plain films are most useful?

Traditional teaching holds that plain abdominal films should include a supine view, plus either

an upright view or a left lateral decubitus view (if unable to stand).

The supine view of the abdomen is the most informative and worthwhile abdominal film.

The upright film is superior for visualizing air-fluid levels associated with ileus, obstruction, or

biliary air. The erect chest radiograph is most sensitive for detection of free intraperitoneal air

and may show basal pneumonia, ruptured esophagus, elevated hemidiaphragm, air-fluid levels

associated with subdiaphragmatic or hepatic abscess, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax. In

the evaluation of patients with abdominal pain, the upright chest film, taken alone, has been

shown to be more useful than films of the abdomen itself.

16. Are air-fluid levels within the intestine always abnormal?

No. It is commonly taught that air-fluid levels when seen on an upright abdominal film are

pathognomonic for small bowel obstruction. A study of 300 normal patients by Gammill

and Nice showed, however, that the average number of air-fluid levels was four per patient,

with some films showing 20. Although typically less than 2.5 cm in length, some were 10

cm. Most of the air-fluid levels were found in the large bowel; only 14 of 300 normal patients

studied showed air-fluid levels in the small bowel. The authors suggested that before air-fluid

levels are used as the sole criterion for the diagnosis of paralytic ileus or mechanical

obstruction, one should see more than two air-fluid levels within dilated loops of the small

bowel.

Chapter 13 ABDOMINAL PAIN90

17. A 7-year-old child presents with acute abdominal pain with a history of

several similar bouts over the past 5 months. Physical examination is

unremarkable. What is the most likely cause?

In children older than age 5, abdominal pain that is intermittent and of more than 3 months’

duration is functional in greater than 95% of cases, especially in the absence of objective

findings such as fever, delayed growth patterns, anemia, GI bleeding, or lateralizing pain and

tenderness.

KEY POINTS: COMMON DISEASES THAT CAN SIMULATE

ACUTE ABDOMEN

1. DKA

2. Food poisoning

3. Pneumonia

4. Pelvic inflammatory disease

WEBSITES

www.emedicine.medscape.com

Acute appendicitis: www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/773895-overview

18. A patient with severe abdominal pain is found to be in diabetic ketoacidosis

(DKA). How do I decide whether the abdominal pain is a manifestation of the

DKA or whether a surgical condition has precipitated DKA?

Patients with established DKA often present to the ED with severe abdominal pain. Although

the precise mechanism of abdominal pain and ileus in patients with DKA is not well

understood, hypovolemia, hypotension, and a total body potassium deficit probably

contribute. An acute surgical lesion may initiate DKA; nevertheless, most patients in DKA have

no such pathology. Abdominal symptoms characteristically resolve as medical treatment

restores the patient to biochemical homeostasis. Treatment of the DKA must precede any

surgical intervention because of the extremely high intraoperative mortality among patients

not so stabilized. If symptoms persist despite adequate correction of DKA, then an underlying

surgical pathology becomes more likely.

19. Is a rectal examination necessary in the patient with suspected acute

appendicitis?

The literature is inconsistent as to its usefulness in aiding the diagnosis; however, failure to

perform a rectal examination is cited frequently in successful malpractice claims. Some other

diseases may be effectively diagnosed only by rectal examination (e.g., prostatitis or occult GI

bleed).

20. Is there a reliable diagnostic test that will either rule in or rule out

appendicitis?

No, not yet anyway. Kentsis et al, have shown that high-accuracy mass spectrometry urine

proteome profiling allowed identification of diagnostic markers of acute appendicitis. These

biomarkers may add significantly to the diagnostic accuracy of appendicitis in the near future.

Chapter 13 ABDOMINAL PAIN 91

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP): Clinical policy: critical issues for the initial evaluation and

management of patients presenting with a chief complaint of nontraumatic acute abdominal pain. Ann Emerg

Med 36:406–415, 2000.

2. Bickerstaff LK, Harris SC, Leggett RS, et al: Pain insensitivity in schizophrenic patients. Arch Surg 123:49–51,

1988.

3. Brewer RJ, Golden GT, Hitch DC, et al: Abdominal pain: An analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases in a university

hospital emergency room. Am J Surg 131:219–233, 1976.

4. Gammill SL, Nice CM: Air fluid levels: Their occurrence in normal patients and their role in the analysis of

ileus. Surgery 71:771–780, 1972.

5. Greene CS: Indications for plain radiography in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 15:257–260,

1986.

6. Jaffe BM, Berger DH: The appendix. In Brunicardi CF, Anderson DK, Billiar TR, et al, editors: Schwartz’s

principles of surgery, ed 8, New York, 2005, McGraw-Hill, pp 1119–1137.

7. Kentsis A, Lin YY, Kurek K, et al: Discovery and validation of urine markers of acute pediatric appendicitis

using high-accuracy mass spectrometry. Ann Emerg Med 55(1):62–70, 2010.

8. Markle GB: Heel-drop jarring test for appendicitis [letter]. Arch Surg 120:243, 1985.

9. McHale PM, LoVecchio F: Narcotic analgesia in the acute abdomen. A review of prospective trials.

Eur J Emerg Med 8:131–136, 2001.

10. Parker LJ, Vukov LF, Wollan PC: Emergency department evaluation of geriatric patients with acute

cholecystitis. Acad Emerg Med 4:51–55, 1997.

11. Ranji SR, Goldman LE, Simel DL, et al: Do opiates affect the clinical evaluation of patients with acute

abdominal pain? JAMA 296:1764–1774, 2006.

12. Rothrock SG, Green SM, Dobson M, et al: Misdiagnosis of appendicitis in nonpregnant women of childbearing

age. J Emerg Med 13:1–8, 1995.

13. Silen W, editor: Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, ed 21, New York, 2005, Oxford University

Press.

14. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL: Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA 276:1589–1594, 1996.

92

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

CHAPTER 14

Juliana Karp, MD

1. Vomiting? Do I really need to read this chapter when there are so many

more interesting chapters in this book?

Yes! One of the most common and harmful mistakes made in the ED is assuming that

nausea and vomiting are the result of gastroenteritis without thinking of and ruling out

more serious causes. In addition, vomiting is one of the most common presenting

complaints in the ED.

2. What causes vomiting?

The act of vomiting is a highly complex act involving a vomiting center in the medulla.

This center may be excited in four ways:

n

Via vagal and sympathetic afferents from the peritoneum; gastrointestinal, biliary, and

genitourinary tracts; pelvic organs; heart; pharynx; head; and vestibular apparatus.

n

By impulses converging at the nucleus tractus solitarius in the medulla.

n

Via the chemoreceptor trigger zone located in the floor of the fourth ventricle.

n

Via the vestibular or vestibulocerebellar system (motion sickness and some

medication-induced emesis).

3. Can vomiting itself lead to potential complications?

Yes. Some of these are life-threatening:

n

Esophageal perforation or Mallory-Weiss tear

n

Severe dehydration

n

Metabolic alkalosis

n

Severe electrolyte depletion (particularly sodium, potassium, and chloride ions)

n

Pulmonary aspiration

n

Esophageal or gastric bleeding

4. List the common gastrointestinal disorders that cause vomiting.

n

Gastroenteritis

n

Gastric outlet obstruction

n

Gastric retention

n

Alcoholic gastritis

n

Pancreatitis

n

Hepatitis

n

Small bowel obstruction

n

Appendicitis

n

Cholecystitis

n

Diabetic gastroparesis

KEY POINTS: CHARACTERISTICS OF GASTROENTERITIS

1. True abdominal or pelvic tenderness is not usually present in gastroenteritis.

2. Gastroenteritis usually consists of both vomiting and diarrhea.

3. Gastroenteritis is usually a self-limited disorder, but IV rehydration and electrolyte

replacement may be necessary.

Chapter 14 NAUSEA AND VOMITING 93

5. Are there different gastrointestinal causes of vomiting in children?

Yes, particularly during the first year of life. These include gastrointestinal atresia, malrotation,

volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease, gastroesophageal reflux, pyloric stenosis, intussusception,

and inguinal hernia. (Vomiting in children presents considerations not covered in this chapter.

See Chapter 63.)

6. List the common causes of vomiting other than gastrointestinal disorders.

n

Infections

n

Pneumonia

n

Meningitis

n

Sepsis

n

Metabolic disturbances (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis, uremia, or hypercalcemia)

n

Toxicologic (e.g., digoxin, theophylline, aspirin, or iron)

n

Cancer chemotherapy

n

Neurologic (e.g., hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, or migraine headache)

n

Renal calculi

n

Ovarian or testicular torsion

n

Pregnancy

n

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

n

Labyrinthine disorders

n

Myocardial ischemia

n

Psychiatric

7. Can the character of the vomit help you to make a diagnosis?

Sometimes, especially with gastrointestinal disorders. In acute gastritis, vomit is usually

stomach contents mixed with a little bile. In biliary or ureteral colic, the vomit is usually

bilious. In sympathetic shock (acute torsion of abdominal or pelvic organ), it is common for

the patient to retch frequently but vomit only a little. In intestinal obstruction, the character of

vomit varies—first gastric contents, then bilious material, with progression to brown feculent

material that is pathognomonic of distal small or large bowel obstruction. Vomiting of blood is

a whole different story (see Chapter 33).

8. What else do I need to ask the patient?

n

Associated signs and symptoms, such as pain, fever, jaundice, and bowel habits. Think of

hepatitis or biliary obstruction with jaundice. Always remember that gastroenteritis is

uncommon without diarrhea.

n

Relationship of vomiting to meals. Vomiting that occurs soon after a meal is common

with gastric outlet obstruction from peptic ulcer disease. Vomiting after a fatty meal is

common with cholecystitis. Vomiting of food eaten more than 6 hours earlier is seen with

gastric retention.

n

Do not always focus on the gastrointestinal system. Ask about medications and possible

drug use, headache and other neurologic symptoms, and last menstrual period and

possibility of pregnancy. Inquire about cardiac risk factors, especially in older patients.

9. What do I look for on the physical examination?

Physical examination is helpful but can be unreliable. Look for signs of dehydration,

particularly in children. Check for bowel sounds, which are increased in gastroenteritis and

absent with obstruction or serious abdominal infections. Abdominal tenderness may be

present in a variety of disorders, but a rigid abdomen points to peritonitis, a surgical

emergency. Women of childbearing age with vomiting and abdominal or pelvic pain require a

pelvic examination and pregnancy test. Always remember the neurologic examination if there

are any associated neurologic symptoms, such as headache or vertigo.

Chapter 14 NAUSEA AND VOMITING94

10. Are laboratory tests indicated?

This question must be answered on an individual basis. In general, tests should be ordered

based on the history and physical examination. Diabetics and elderly patients can hide serious

infections and metabolic disturbances. Be careful with these patients.

11. When should I order radiographs?

This must be judged on an individual basis. Abdominal radiography is usually nonspecific but

may show free air with perforation of an abdominal viscus or dilated bowel with obstruction.

A chest film can be useful in cases of protracted vomiting to rule out aspiration or

pneumomediastinum. Lobar pneumonia with diaphragmatic irritation may cause vomiting with

abdominal pain and few respiratory symptoms.

KEY POINTS: DIAGNOSIS OF THE VOMITING PATIENT

1. Always consider etiologies other than gastrointestinal disorders.

2. Take a thorough history, especially in the young and elderly.

3. Always consider accidental ingestions in children and medication side effects or

toxicities in adults.

4. Laboratory testing and radiographs are seldom useful in gastroenteritis but may be

helpful to identify other causes of vomiting.

12. How should I treat the vomiting patient?

a. Always remember to protect the airway. Patients with altered mental status should be

placed on their side to prevent aspiration. Intubate early when necessary.

b. Intravenous (IV) fluids usually are indicated for rehydration; normal saline or lactated

Ringer solution is preferred.

c. Nasogastric suction can be therapeutic and diagnostic and is always indicated when there

is a suspicion of a gastrointestinal bleed or small bowel obstruction.

d. Medications to relieve nausea and vomiting must be used judiciously, especially in patients

with altered mental status, hypotension, or uncertain diagnosis.

e. Determine and, if possible, treat the underlying cause.

13. What medications should I use?

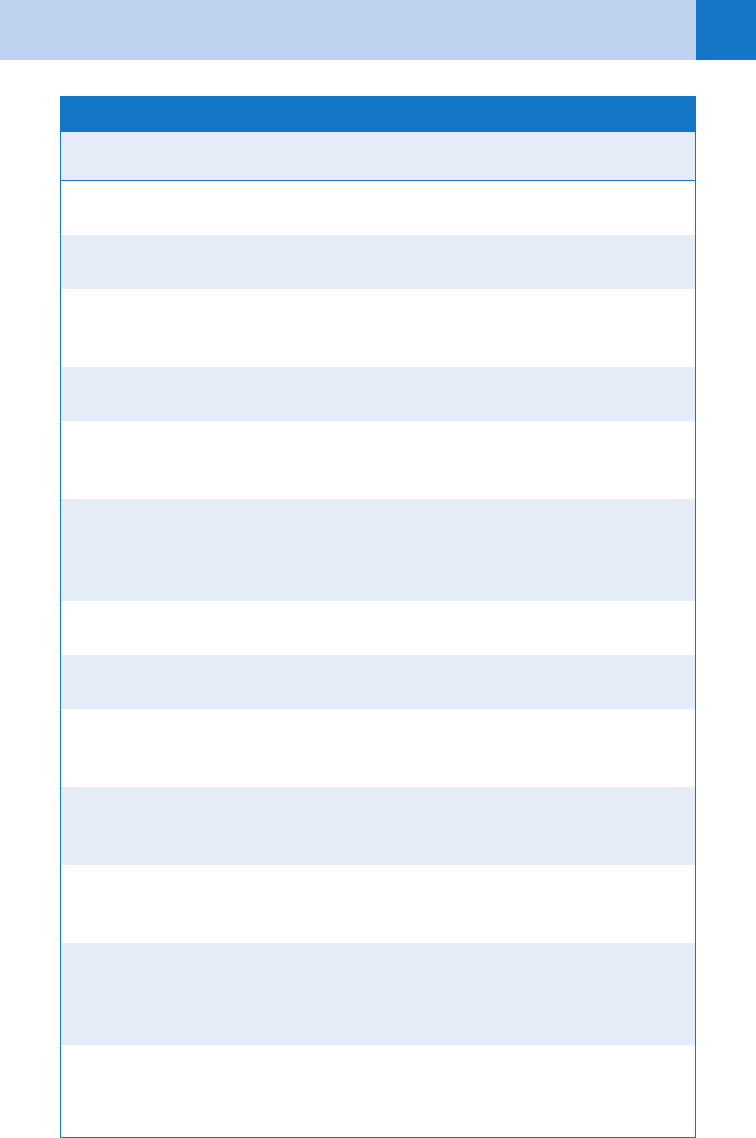

See Table 14-1.

WEBSITES

www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch

Chapter 14 NAUSEA AND VOMITING 95

Generic Name

Trade

Name Indication Dose

Palonosetron Aloxi Vomiting with

chemotherapy

0.25 mg IV prior to

chemotherapy

Meclizine Antivert Vertigo and motion

sickness

25 mg PO qid

Dolasetron

mesylate

Anzemet Vomiting associated with

anesthesia or

chemotherapy

12.5–100 mg PO or IV

single dose

Hydroxyzine Atarax Nausea, vomiting, anxiety 25–100 mg PO or IM tid

or qid

Diphenhydramine

Nabilone

Benadryl

Cesamet

Motion sickness

Nausea and vomiting with

chemotherapy

25–50 mg PO or IV qid

1–2 mg PO bid

Prochlorperazine

Dimenhydrinate

Compazine

Dramamine

Nausea, vomiting, anxiety

Nausea, motion sickness

10 mg PO, IM, or IV qid,

25 mg PR bid

50–100mg PO, IM,

or IV qid

Aprepitant Emend Nausea and vomiting,

with chemotherapy

125 mg PO on day 1, 80

mg PO on days 2 and 3

Phosphorated

carbohydrate

Emetrol Nausea and vomiting, 1–2 tbs PO every 15 min

(not to exceed 5 doses)

Droperidol Inapsine Nausea and vomiting 0.625–2.5 mg IV or 2.5 IM

(black box warning: QT

prolongation)

Granisetron Kytril Nausea and vomiting with

chemotherapy

10 mg/kg IV or 1 mg PO

bid (only on day of

chemotherapy)

Dronabinol Marinol Refractory nausea and

vomiting with

chemotherapy

5 mg PO tid or qid

Promethazine Phenergan Nausea, vomiting, motion

sickness, anxiety

12.5–50 mg PO, PR, or IV

qid (black box warning:

children younger than

2 years old)

Metoclopramide Reglan Nausea, vomiting, gastro-

esophageal reflux,

gastroparesis

5–10 mg PO or IV dosage

varies (box warning,

tardive dyskinesia)

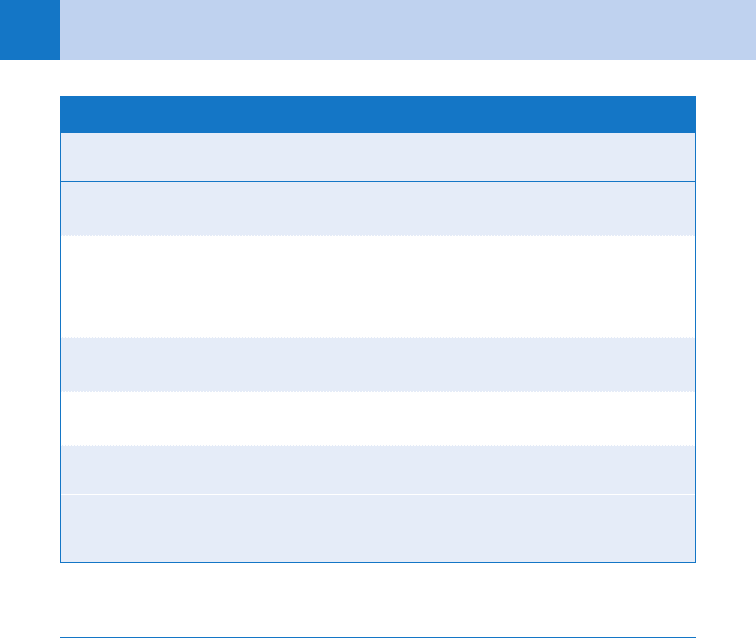

TABLE 14-1. ANTIEMETIC MEDICATIONS

Continued

Chapter 14 NAUSEA AND VOMITING96

Generic Name

Trade

Name Indication Dose

Chlorpromazine Thorazine Nausea, vomiting, anxiety 10–25 mg PO qid, 25 mg

IM, or qid 100 mg PR qid

Trimethobenzamide

Thiethylperazine

Torecan

Tigan

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting

250 mg PO tid or qid , 200

mg PR tid or qid , 200 mg

IM tid or qid

Dosage varies

Scopolamine Transderm

Scop

Nausea, vomiting, motion

sickness

1 patch every 3 days

Hydroxyzine

pamoate

Vistaril Nausea, vomiting, anxiety 25–100 mg PO or IM tid

or qid

Ondansetron Zofran Nausea and vomiting 4 mg IV or IM

TABLE 14-1. ANTIEMETIC MEDICATIONS—cont’d

bid, twice a day; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, per os (by mouth); PR, per rectum; qid, four times

a day; tid, three times a day.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Ernst A: Prochlorperazine versus promethazine for uncomplicated nausea and vomiting in the emergency

department: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 36:89–94, 2000.

2. Wolfson, AB, Hendey, GW, Hendry PL, et al, editors: Harwood-Nuss’ clinical practice of emergency medicine,

ed. 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

3. Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, editors: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 7,

St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.

4. Silen W, editor: Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, ed 21, New York, 2005, Oxford University Press.

97

CHAPTER 15

HEADACHE

Jonathan A. Edlow, MD, FACEP

1. How common are headaches and what percentage of ED patients have

headache as a chief complaint?

Nearly everyone has a headache at some point in their lives; migraine headache is found

in about 12% of the general population. Most patients do not seek medical care,

certainly not in the ED. Overall, approximately 2% of all ED visits are for headaches.

Of those who come to the ED with headache, only about 5% will have a serious cause.

2. When someone has a headache, what exactly is it that hurts?

The brain, the pia and arachnoid mater, the skull, and the choroid plexus are not the

source of headache pain. The structures in the head that are pain sensitive include the

scalp; skin; vessels; scalp muscles; parts of the dura mater; dural arteries; intracerebral

arteries; cranial nerves V, VI, and VII; and the cervical nerves. Irritation, inflammation,

distention, or traction of any of these may result in a headache.

3. Name the most common headaches for which patients seek treatment.

Muscle contraction (tension) and vascular (migraine) headaches are by far the most

common, even in an acuity-skewed ED population. These are often referred to as

primary headache disorders. Although painful, these disorders do not have life-

threatening sequelae. There are a number of cannot miss causes of headache that,

although less common, are crucial for emergency physicians to diagnose correctly.

4. What causes of headache are cannot miss?

True emergencies, or cannot miss causes of headaches, are conditions that threaten life, limb,

brain, or eye and treatable (see Table 15-1). Headaches that are true emergencies include:

n

Intracranial bleeding (subarachnoid hemorrhage; SAH)

n

Subdural or epidural hematoma

n

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

n

Ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA)

n

Dissection of a carotid or vertebral artery

n

Hypertensive encephalopathy

n

Brain tumor

n

Giant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis) and other vasculitides

n

Central nervous system infections (meningitis and abscess)

n

Pseudotumor cerebri

n

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

n

Narrow angle glaucoma

n

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension

5. What are some clinical clues to distinguish primary headaches from

cannot miss headaches?

By definition, tension and migraine headaches are recurrent episodes; these episodes

are usually similar to one another in any one individual patient. Therefore, any first

severe headache can never be definitively diagnosed as tension or migraine. A headache

that is described as a first or worst headache, or even substantially different from prior