Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 16 SYNCOPE, VERTIGO, AND DIZZINESS108

9. What targeted bedside tests aid in the diagnosis of vertigo?

Examine the eyes for ocular palsies and nystagmus. Examine the ears for infection,

perforation, and hearing function (using the Weber and Rinne tests). Perform a full neurologic

examination including cranial nerves, gait, stance, and cerebellar function. The Dix-Hallpike

and Epley for BPPV and head thrust maneuvers to diagnose labyrinthitis or neuronitis may be

beneficial if these specific etiologies are suspected.

10. How is nystagmus evaluated in the work-up of vertigo?

With peripheral etiologies, asymmetric impulses from the semicircular canals cause the eyes to

drift toward the diseased side and correct with the fast component of nystagmus to the opposite

normal side. By convention, the direction of the fast component determines the direction. Vertical,

changing direction, and nonsuppressible nystagmus are characteristics of central etiologies.

11. What is the head thrust maneuver? What does it mean?

The examiner stands in front of the patient and holds the patient’s head in both hands

instructing the patient to look at the examiner’s nose. The head is rapidly turned 5 to 10

degrees to one side and the response of the eyes is noted. Normally, the eyes continue to fix

on the examiner’s nose (intact vestibulo-ocular reflex), but if one side has a unilateral lesion

such as vestibular neuritis, the eyes don’t stay fixed on the target and need to correct to

refocus on the target after head movement. Turning the head in the opposite direction serves

as control. A patient with unidirectional horizontal nystagmus, a positive head thrust test

opposite the fast phase direction of the nystagmus and no other neurological features, is likely

to have vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis.

12. What is the Dix-Hallpike maneuver?

This diagnostic maneuver tests for BPPV and involves moving the patient rapidly from a

sitting position with the head turned 45 degrees to one side with the head hanging down in a

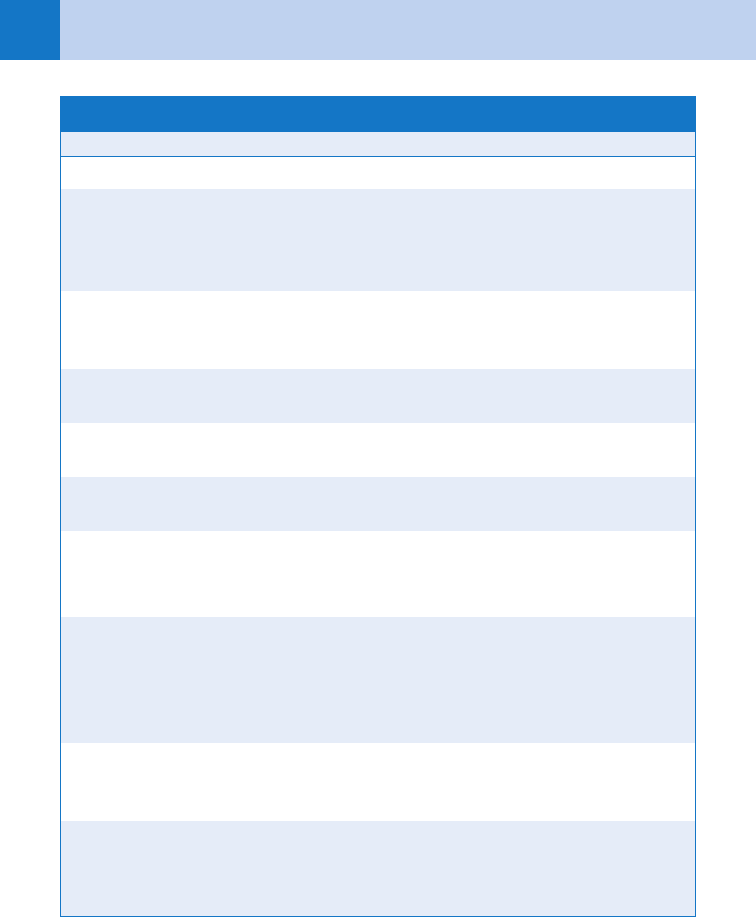

TABLE 16-1. KEY POINTS FOR THE MAIN CAUSES

OF PERIPHERAL VERTIGO

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Most common cause (50%)

Recurrent ,1 minute paroxysms elicited with head turning

Normal between brief attacks

Due to otolith dislodgement into a semicircular canal

Responds to Epley maneuver

Vestibular Neuritis

Less common cause (20%)

Probable viral etiology

Positive asymmetric head thrust test

May respond to steroids

Ménière Disease

Less common cause (10%)

Less acute onset (hours)

Associated with hearing loss, tinnitus

Due to high endolymph volume

Responds to diuretics or fluid restriction

Chapter 16 SYNCOPE, VERTIGO, AND DIZZINESS 109

supine position. Nystagmus, often toward the dependent eye or forehead, is characteristically

associated with a delay of a few seconds and fatigable symptoms of vertigo on repetition.

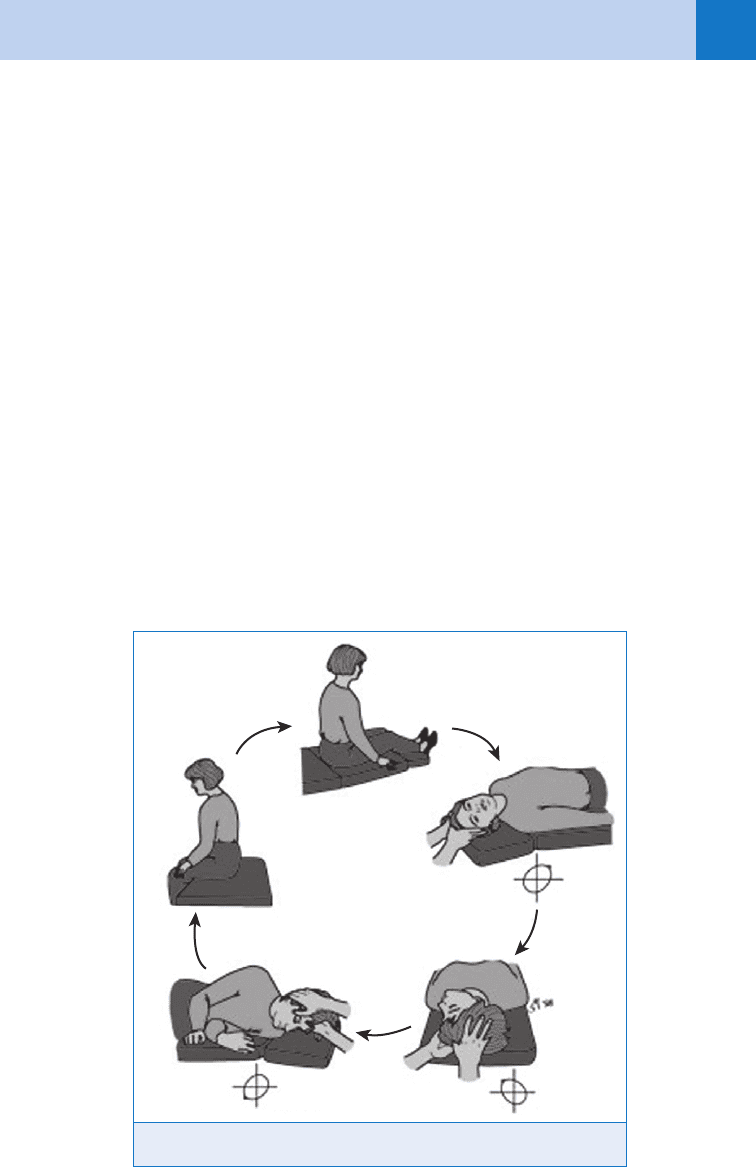

13. What is the Epley maneuver?

The Epley maneuver treats BPPV and is utilized to physically move otoliths, most commonly

in the posterior semicircular canal into the utricle. It is successful about 75% of the time on

first attempt and up to 98% on two attempts. The technique involves performing the Dix-

Hallpike maneuver, then turning the head to the opposite side while still supine and then

turning over in the same direction prior to rising. (See Fig. 16-1)

14. How do I treat peripheral (and central) vertigo?

Vestibular neuritis benefits from steroids in a 22-day taper. BPPV is treated by the Epley

maneuver. Nonspecific vestibular suppressants include:

n

Anticholinergics (e.g., scopolamine transdermal)

n

Antihistamines (meclizine 25–50 mg PO every 6 hours, dimenhydrinate 50 mg PO every

4–6 hours, and diphenhydramine 25–50 mg PO every 4–6 hours)

n

Benzodiazepines (diazepam 5–10 mg PO every 6 hours)

Central vertigo requires evaluation by neurology or neurosurgery. If the patient cannot walk or

has intractable symptoms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the posterior fossa

and brainstem and admission is recommended.

15. What is syncope?

A sudden temporary loss of consciousness with the inability to maintain postural tone. It is a

symptom, not a disease, with a wide variety of benign and life-threatening causes. Coma, head

trauma, shock, and seizures may mimic syncope.

A

B

C

D

E

Figure 16–1. Epley maneuver.

Chapter 16 SYNCOPE, VERTIGO, AND DIZZINESS110

16. What are the odds of determining the cause of a syncopal episode?

Despite extensive and expensive work-ups, no cause is found in about 50% of cases. This

should be discussed with the patient so that there are no unrealistic expectations.

KEY POINTS: CAUSES OF SYNCOPE

1. HEAD (hypoxemia, epilepsy, anxiety, dysfunctional brain)

2. HEART (heart attack, embolism of pulmonary artery, aortic obstruction, rhythm disturbance,

tachydysrhythmia)

3. VESSELS (vasovagal, ectopic, situational, subclavian steal, ENT, low systemic vascular

resistance, sensitive carotid sinus)

17. Discuss the causes of syncope as related to the head.

Diffuse cerebral malfunction from lack of vital nutrients, such as oxygen (hypoxemia) or sugar

(hypoglycemia), are often correctable, but easily overlooked. Seizures don’t cause but can

mimic syncope. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency and SAH represent a dysfunctional brain.

18. Discuss the cardiovascular causes of syncope.

Cardiac causes of syncope comprise the riskiest group of patients and include acute coronary

syndrome (ACS), pulmonary embolism, physical aortic outflow obstructions (from

hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis, and atrial myxoma), slow rhythms

such as sick sinus syndrome, and tachyarrhythmias. Brugada syndrome, pre-excitation, and

long QT syndrome can precipitate lethal dysrhythmias.

19. What about the vascular causes of syncope?

Vascular causes include:

n

The common faint (vasovagal)

n

Hypovolemia

n

Situational faints (e.g., micturition, defecation, cough, or Valsalva maneuver)

n

Subclavian steal

n

Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) causes (e.g., glossopharyngeal and trigeminal neuralgia)

n

Low systemic vascular resistance (from medications and autonomic insufficiency)

n

Carotid sinus sensitivity (only accounting for 4% of syncope cases)

20. Summarize the initial concerns when treating a patient with syncope.

Most patients with syncope rapidly return to a normal mental status and have stable vital

signs. There are treatment priorities, however.

a. Obtain vital signs and evaluate and treat for immediate life threats.

b. Oxygen, intravenous access, and cardiac and blood pressure monitoring should be initiated

on patients who have abnormal vital signs, a persistent altered level of consciousness,

chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, or a significant history of cardiac disease.

c. Assess for any trauma secondary to fall. Elderly patients are more likely to suffer head

trauma secondary to syncope, and this may be a greater life threat initially than the cause

of the syncope.

21. Okay, I’ve ruled out the immediate life threats. Now what do I do?

Obtain a detailed history, do a directed physical examination, and obtain an electrocardiogram

(ECG). Then do a risk assessment to determine whether further testing or admission is

indicated.

Chapter 16 SYNCOPE, VERTIGO, AND DIZZINESS 111

22. What components of the history are most important?

The most important historical clue is the patient’s recollection of the events just before the

syncope. An abrupt onset of loss of consciousness with a brief (,5 seconds) prodrome is

indicative of a cardiac etiology. Similarly, syncope associated with exercise, or while reclining

or recumbent, is associated with cardiac obstructive causes or arrhythmias. Patients who have

vasovagal syncope often have premonitory symptoms of dizziness, yawning, nausea, and

diaphoresis, and the event is during a period of some psychosocial stress. Clues to

hypovolemia include thirst, postural dizziness, decreased oral intake, melena, or unusually

heavy vaginal bleeding. Syncope after micturition, cough, head turning, defecation,

swallowing, or meals suggests situational syncope. Note previous episodes of syncope, upper

extremity exertion (e.g., subclavian steal syndrome), and the presence of cardiac risk factors.

A family history of sudden death may suggest Brugada, pre-excitation, or long QT syndromes.

Many medications and medication interactions can cause syncope, so determine all of the

patient’s current medications, especially when treating the elderly.

23. How do I know it was not a seizure?

Victims of arrhythmias and vasovagal faints often exhibit myoclonic jerks that may mimic a

seizure. Recovery from syncope is usually rapid, whereas a generalized seizure patient

awakens slowly with prolonged confusion or postictal state. Both may have trauma. The

absence of an anion gap on blood drawn within 30 minutes of the event or no postictal state

argues against a generalized seizure. Lateral tongue biting has been shown to be specific but

insensitive for a seizure.

24. What is a directed physical examination?

Be a detective, using head, heart, and vessels as a guide. The patient with abrupt effort or

exercise syncope may have aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; look for narrow

pulse pressure, systolic murmur, or change in murmur with Valsalva. The presence of physical

signs of congestive heart failure (CHF) places the patient at high risk. Examine the head

carefully for trauma, bruits, and focal neurologic signs. Check blood pressure in both arms

looking for subclavian steal. Search for occult blood loss or autonomic insufficiency.

25. What tests are needed to assist in diagnosis?

Other than a urine pregnancy test in females, a detailed history, physical examination, and

ECG are often sufficient. The addition of a specific confirmatory test (e.g., echocardiography)

is recommended for suspected cardiomyopathy.

26. Who needs an ECG? What am I looking for?

Almost all patients with syncope should have an ECG because it is not invasive, may be

diagnostic of a problem such as Brugada syndrome or long QT, and helps in risk stratification

for ACS. Check for markers of cardiac disease, such as ischemia, infarction, arrhythmias,

pre-excitation, long QT intervals, and conduction abnormalities. Left ventricular hypertrophy

may be a clue to aortic stenosis, hypertension, or cardiomyopathy.

27. If the basic evaluation is not diagnostic, who should receive further testing?

Patients with CHF, older age, abnormal ECG and unexplained syncope who have suspected

heart disease should be admitted and evaluated for an acute coronary syndrome.

Echocardiography, exercise treadmill testing, Holter ECG monitoring, and electrophysiologic

studies also may be helpful.

28. What factors help to assign a patient to a high-risk or low-risk group?

Physician gestalt plays a large role. Studies attempting to determine highly sensitive risk

factors have had mixed results (see Table 16-2). For example, the San Francisco Syncope Rule

was found to have only 75% sensitivity on external validation.

Chapter 16 SYNCOPE, VERTIGO, AND DIZZINESS112

29. My consultant wants orthostatic vital signs; are they helpful?

Yes and no. Orthostatic hypotension (defined as a blood pressure drop of 20 mm Hg on

standing for 3–4 minutes) is associated with volume loss or autonomic insufficiency and an

increased risk of fall and syncope. However, parameters for orthostatic hypotension are

neither sensitive nor specific. A blood pressure drop of 20 mm Hg has only 29% sensitivity

and 81% specificity for 5% or greater fluid deficit. Of normal euvolemic patients older than

65 years, more than 25% generate false-positive results. Reproducible symptoms are a better

predictor than any number change.

30. Are there guidelines for the evaluation of syncope?

Yes.

a. American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP): Clinical policy: critical issues in the

evaluation and management of patients presenting with syncope. Ann Emerg Med 49:771, 2007.

b. Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt DG, et al: Guidelines on management (diagnosis and

treatment) of syncope-Update 2004. Europace 6:467–537, 2004.

c. Strickberger SA, Benson W, Biaggioni I, et al: AHA ACCF Scientific statement on the

evaluation of syncope. Circulation 113:316, 2006.

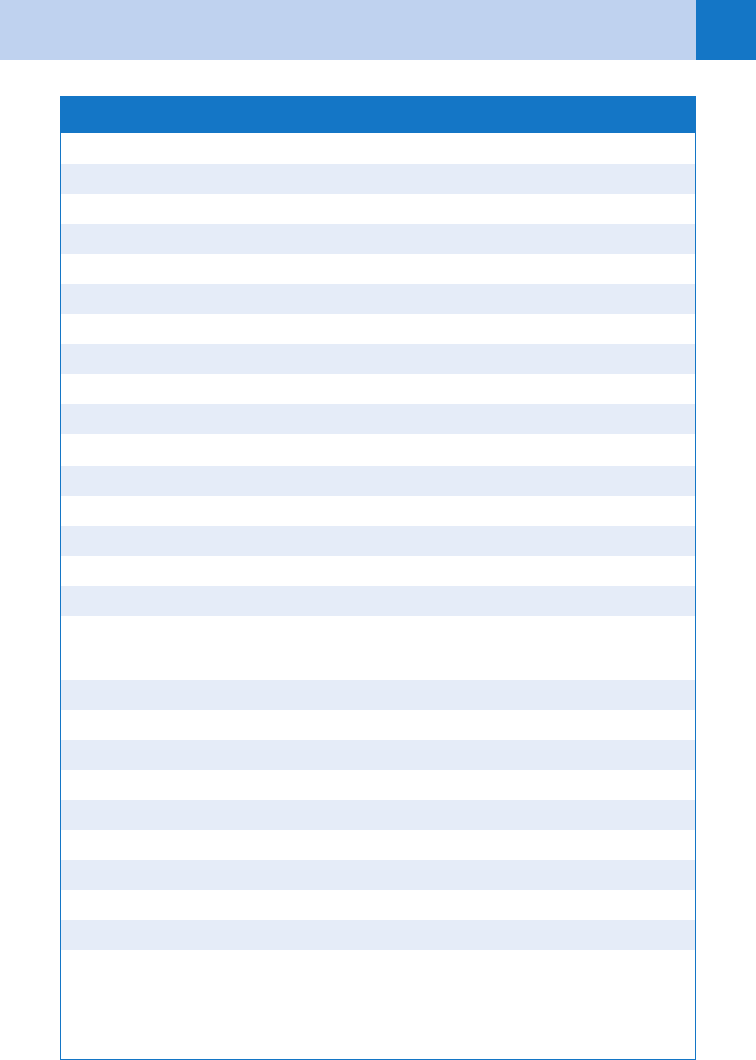

TABLE 16-2. SYNCOPE AT HIGH RISK FOR CARDIAC ETIOLOGY

Historical ED evaluation

Age .65 years

Cardiovascular disease history

Lack of prodrome

Exertional

Chest pain with event

Palpitations preceding the event

Family history of sudden death

Abnormal vital signs

Systolic blood pressure ,90

Evidence of congestive heart failure

Abnormal electrocardiogram

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvida L, et al: Clinical practice guideline; benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Otolaryngology 139:S47, 2008.

2. Birnbaum A, Esses D, Bijur, et al: Failure to validate the San Francisco syncope rule in an independent

emergency department population. Ann Emerg Med 52:151, 2008.

3. Chan Y: Differential diagnosis of dizziness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 17:200, 2009.

4. Colivicchi F, Ammirati F, Melina D, et al: Development and prospective validation of a risk stratification system

for patients with syncope in the emergency department: the OESIL risk score. Eur Heart J 24:811, 2003

5. Costantino G, Perego F, Dipaola F, et al: Short and long term prognosis of syncope, risk factors and role of

hospital admission. J Am Coll Cardiol 51:276, 2008.

6. Del Rosso A, Ungar A, Maggi R, et al: Clinical predictors of cardiac syncope at initial evaluation in patients

referred urgently to a general hospital: EGSYS score. Heart 94:1620, 2008.

7. Edlow JA, Newman-Toker DE, Savitz SI: Diagnosis and initial management of cerebellar infarction. Lancet

7:951, 2008.

8. Grossman SA, Fischer C, Lipsitz L, et al: Predicting adverse outcomes in syncope. J Emerg Med 33:233,

2007.

9. Kerber KA: Vertigo and dizziness in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 27:39, 2009.

10. Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, West BT, et al: Dizziness presentations in US emergency departments, 1995–2004.

Acad Emerg Med 15:744, 2008.

11. Seemungal BM, Bronstein AM: A practical approach to acute vertigo. Pract Neurol 8:211, 2008.

12. Strupp M, Zingler VC, Arbusow V, et al: Methylprednisolone, valacyclovir, or the combination for vestibular

neuritis. N Engl J Med 351:354, 2004.

113

CHAPTER 17

SEIZURES

Kent N. Hall, MD

1. What is a seizure?

A seizure is an episode of abnormal brain function caused by excessive and aberrant

electrical discharge in the brain. This electrical discharge may, or may not, result in

characteristic muscle activity that is recognized as seizure activity. In addition to tonic-

clonic muscle activity, generalized seizures may also manifest as staring episodes, lip

smacking or other minor motor activity, or complete disruption of muscle tone (drop

attacks). Generalized seizures are often followed by a postictal phase characterized by

confusion and/or lethargy. This phase usually lasts for 5 to 15 minutes, although it may

last longer.

The recognition and appropriate management of seizures are critically important to

the patient and the emergency physician because they are a common ED presenting

problem. Prolonged excessive electrical activity in the brain causes neuronal destruction.

This destruction is not due to build-up of metabolic by-products but is actually directly

related to the electrical activity itself. For an unknown reason, the hippocampus is

particularly sensitive to the damage from this electrical activity.

2. How are seizures classified?

Seizures are classified according to the amount of brain involved in the abnormal

electrical activity, its resulting physical manifestation, and its underlying cause. In

general, seizures are divided into two groups, generalized and focal (Table 17-1).

Generalized seizures affect a large volume of brain tissue in the abnormal electrical

activity, whereas focal seizures involve a specific brain area. Because of this, the

manifestations of focal seizures, whether simple or complex, may lead to bizarre

manifestations including hallucinations, memory disturbance, visceral symptoms

(abdominal symptoms), and perceptual distortions. This has often resulted in the

patient with partial seizures being misdiagnosed as having a psychiatric problem.

Often the emergency physician is presented with a patient who is not actively seizing

but has had a seizure. In this case, it is important to evaluate for secondary signs of

seizure activity. These include bowel or bladder incontinence, biting of the tongue or

buccal mucosa, and postictal confusion.

3. What are the causes of seizures?

Seizures are abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Primary seizures are recurrent

episodes without an underlying cause. This is classically referred to as epilepsy.

Secondary seizures (also called reactive seizures) have a (usually non-neurologic)

underlying condition. Table 17-2 lists the most common etiologies for secondary

seizures.

4. What is included in the differential diagnosis of seizure?

Anything that can cause a sudden disturbance of neurologic function may be mistaken

for a seizure. Common processes that fall into this category include syncope,

hyperventilation syndrome, migraines, movement disorders, and narcolepsy.

Pseudoseizure is a special category and is discussed later.

Chapter 17 SEIZURES114

5. What should my priorities be in managing a patient who is actively seizing?

Clinical priorities are the ABCs. Attention is always directed to the airway first. It is rare that a

seizure patient needs to be intubated. Supplemental oxygen, usually via nasal cannula, should

be given because of the increased oxygen demand caused by the generalized muscle activity.

Supplemental ventilation (bag-valve-mask) is rarely needed. Evaluation of the circulatory

status can be readily accomplished by noting blood pressure, pulse, and capillary refill. Check

the temperature and administer antipyretics in appropriate doses when needed.

Airway protection can usually be accomplished by positioning the patient on his or her

side. Suctioning of the patient’s oral secretions will also help decrease the chance of

aspiration. However, nothing should be put into the patient’s mouth that might be bitten off

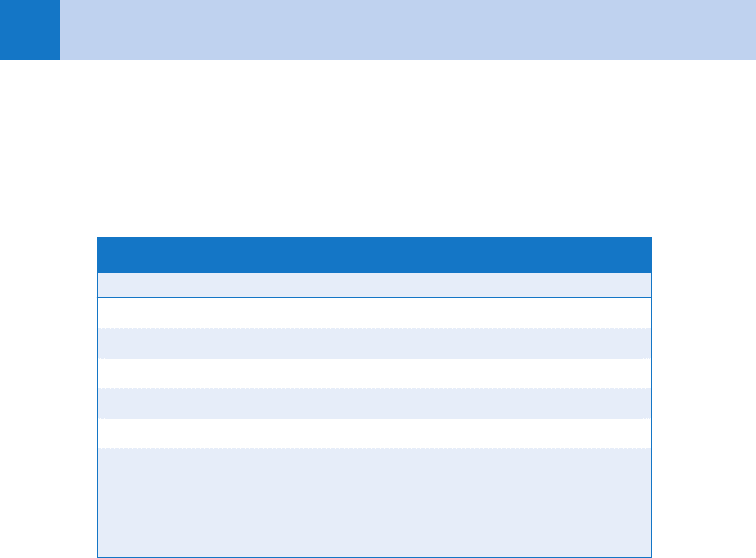

TABLE 17-1. CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES

Type Manifestations

Generalized

Tonic-clonic (grand mal) Loss of consciousness followed immediately by tonic contractions

of muscles, then clonic contractions of muscles (jerking) that

may last for several minutes. A period of disorientation (postictal

period) occurs after the tonic-clonic activity.

Absence (petit mal) Sudden loss of awareness with cessation of activity or body

position control. The period usually lasts for seconds to minutes

and is followed by a relatively short postictal phase.

Atonic (drop attacks) Complete loss of postural control with falling to the ground,

sometimes causing injury. It usually occurs in children.

Myoclonic Brief, vigorous, spasmodic muscle contractions. These may affect

the entire body or only specific areas.

Tonic Prolonged muscle contraction. It occurs usually with associated

deviation of the head and eyes in a particular direction.

Clonic Repetitive jerking motions occur without any associated tonic

muscle contraction.

Partial or focal

Simple partial Multiple patterns are possible depending on the area of the

brain affected. If the motor cortex is involved, the patient will have

contraction of the corresponding body area. If nonmotor areas

of the brain are involved, the sensation may be paresthesias,

hallucinations, or déjà vu.

Complex partial Usually there is loss of ongoing volitional major motor activity with

repetitive minor motor activity, such as lip smacking and walking

aimlessly.

Partial with secondary

generalization

Initial manifestations are the same as partial. However, the activity

progresses to involve the entire body, with loss of postural control

and possibly tonic-clonic muscle activity.

Chapter 17 SEIZURES 115

TABLE 17-2. ETIOLOGIES OF SECONDARY SEIZURES

Metabolic

Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia

Hyponatremia, hypernatremia

Hypocalcemia

Hypomagnesemia

Uremia

Hypothyroidism

Hepatic encephalopathy

High anion gap acidosis

Fever (“febrile seizures”)

Infectious diseases

Meningitis

Encephalitis

Cerebral abscess

Cerebral parasitosis

HIV

Drugs/toxins (multiple)

Subtherapeutic antiepileptic drug levels

Cocaine, lidocaine

Antidepressants

Theophylline

Alcohol withdrawal

Drug withdrawal

Structural

Trauma (recent and remote)

Intracranial hemorrhage

Vascular lesions

Mass lesions

Eclampsia

Hypertensive encephalopathy

Chapter 17 SEIZURES116

6. What do I do if the patient doesn’t stop seizing?

Most seizures last for less than 2 minutes. When a seizure lasts longer, pharmacologic

intervention is generally indicated. Benzodiazepines are the accepted first-line therapy.

The intravenous (IV) route is the preferred route of administration. Lorazepam (2–4 mg

intravenously) is the conventional first choice because of theoretical issues related to duration

of action. However, diazepam (5–10 mg intravenously) may also be used. Diazepam may be

administered intravenously, rectally, or intraosseously but is not recommended for

intramuscular use because of uneven uptake.

Once the seizure has ceased, anticonvulsants are used to keep it from recurring. Phenytoin

is considered the first-line therapy. Table 17-3 shows the medications in this class along with

their dosage and route of administration.

7. What is status epilepticus? How is it managed?

When seizures last longer than 5 minutes despite acute pharmacologic intervention or recur

so frequently that normal mentation does not resume between the seizures, it is called status

epilepticus. In this case, immediate pharmacologic intervention is indicated. Table 17-4 gives

an algorithm that can be used to manage the patient with status epilepticus.

8. Is the history important?

The history if vitally important! The mnemonic COLD can be used to ensure you have covered

the aspects of the seizure activity itself.

n

Character: What type of seizure activity occurred?

n

Onset: When did it start? What was the patient doing?

n

Location: Where did the activity start?

n

Duration: How long did it last?

In general, seizures start abruptly, are stereotyped (similar seizure activity recurs from attack

to attack in an individual patient), are not provoked by environmental stimuli, are manifested

by purposeless or inappropriate motor activity, and except for petit mal seizures, are followed

by a period of confusion or lethargy (the postictal phase). Other important historical aspects

include the patient’s past medical history (especially previous seizure history), alcohol use,

(including fingers) and thus become an obstructing foreign body. Gently restraining the

patient so he or she is not harmed is also important.

Diagnostic priorities should focus on likely secondary causes of seizures that are

reversible. Hypoglycemia is a common cause of secondary seizures that is treatable with rapid

results. Similarly, immediate evaluation of significant electrolyte abnormalities (i.e., sodium,

calcium, magnesium) in a patient with prolonged seizure activity is warranted.

TABLE 17-3. ANTICONVULSANTS

Drug Adult dose

Phenytoin 15–20 mg/kg IV at ,50 mg/min

Fosphenytoin 15–20 mg PE/kg at 100–150 mg PE/min; may be given IM

Phenobarbital 20 mg/kg IV at 60–100 mg/min. May be given as IM loading dose

Valproate 15–30 mg/kg IV should be given over one hour

Pentobarbital 5 mg/kg IV at 25 mg/min, then titrate to EEG. Intubation required

Isoflurane Via general endotracheal anesthesia

EEG, electroencephalogram; IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PE, phenytoin sodium equiva-

lents; PR, per rectum.

Chapter 17 SEIZURES 117

toxic ingestions, current medications, any history of central nervous system (CNS)

neoplasms, and history of recent or remote trauma.

9. In addition to the neurologic examination, what other parts of the physical

examination are important?

A complete head-to-toe examination is important. In addition to looking for causes of the

seizure, the physician should look for trauma caused by the seizure. The examination is often

normal but occasionally may give clues to an underlying problem. Specifically, examination of

the skin might reveal lesions from meningococcemia, other infectious problems, or stigmata

of liver failure. Examine the head for trauma. If nuchal rigidity is found, meningitis or

subarachnoid hemorrhage should be suspected.

The neurologic examination is most important. Focal neurologic findings, such as focal

paresis after the seizure (Todd’s paralysis), may indicate a focal cerebral lesion (i.e., tumor,

abscess, or cerebral contusion) as the cause of the seizure. Evaluation of the cranial nerves

and the fundi can point to increased intracranial pressure.

10. What ancillary testing should I do in the patient with a history of seizures?

Extensive ancillary testing is reserved for the patient with new onset seizure. For patients with

a prior history of seizures who have an unprovoked attack, measurement of appropriate serum

anticonvulsant levels is all that is required. The decision to proceed with further testing

depends on the patient’s history and physical findings at the time of presentation. If there is a

question whether the patient had a major motor seizure, then measurement of the anion gap

within 1 hour of the seizure might be of benefit.

TABLE 17-4. PROPOSED GUIDELINES FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE PATIENT WITH STATUS EPILEPTICUS

Time Frame Measures

Establish/maintain airway

IV/oxygen/monitor

0–5 min Dextrose, 0.5 gm/kg IV, if indicated

Consider thiamine, 100 mg IV, and magnesium 1–2 gm IV for alcoholic or

malnourished patients

Lorazepam, 1 mg per min IV up to 0.1 mg/kg (or diazepam, 5 mg IV every

5 min up to 20 mg)

10–20 min Phenytoin, 20 mg/kg IV at 50 mg/min, or fosphenytoin, 20 mg/kg PE IV at

150 mg/min

Phenobarbital up to 20 mg/kg IV at 50–75 mg/min IV

Valproate up to 30 mg/kg IV over 1 hour

30 min And/or

General anesthesia with midazolam, 0.2 mg/kg slow IVP, then

0.75–10 mg/kg/min

Or propofol, 1–2 mg/kg IV, then 1–15 mg/kg/hr

Or pentobarbital, 10–15 mg/kg IV over 1 hour, then 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/hr

IV, intravenous; IVP, intravenous push; PE, phenytoin sodium equivalents. Adapted from Lowenstein DH,

Aldredge BK: Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 338:970, 1998.