Malley M.C. Radioactivity: A History of a Mysterious Science

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

A NEW SCIENCE

38

primary x rays. What was the energy source for the Becquerel rays?

Perhaps, suggested Marie Curie, space is full of some unknown

radiation which supplies radioactivity’s energy. When uranium and

thorium absorb this radiation, they emit secondary rays as a type of

phosphorescence. Curie’s colleague Sagnac had recently found that

x rays were absorbed best by the heaviest elements. Since thorium

and uranium were heavy elements, Curie’s idea t well.

inking the radiation might come from the sun, the Curies

compared uranium’s activity at noon to its activity at midnight. At

midnight, the radiation would need to pass through the earth to

reach the uranium sample. If the earth absorbed some of this radia-

tion, the midnight reading would be less than the reading at noon.

However, the readings were identical. e Curies were so puzzled

by the ongoing failures to nd radioactivity’s energy source that

they were willing to consider a breach in the bedrock principle of

energy conservation. Perhaps radioactivity was an exception to

that rule. Sir William Crookes had also wondered whether radio-

activity violated physical laws by gleaning its energy from motions

of air molecules.

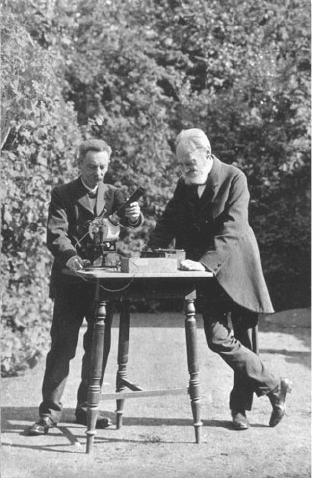

Two German physicists performed extensive tests in 1898–99

to locate radioactivity’s source. Julius Elster and Hans Geitel

were schoolteachers and respected physicists who had set up a

private laboratory in Elster’s home in the old medieval town of

Wolfenbü el. ey had been friends since childhood and did most

of their research together, so that the term “Elster-Geitel” signi ed

a unit in the scienti c community.

For years Elster and Geitel had investigated electrical e ects

in the atmosphere in order to understand weather phenomena,

a popular research topic in the nineteenth century (Figure 3-2).

When they learned of Becquerel’s discovery, they wondered

whether radioactivity might a ect weather, and decided to

RUTHERFORD, SODDY, PARTICLES, AND ALCHEMY?

39

investigate the new phenomenon. Elster tried in vain to in uence

uranium’s radiations with light and with heating. To see whether

something in the air caused radioactivity, Elster and Geitel placed

pitchblende and a uranium salt in a vacuum, then varied the air

pressure. e radioactivity was not a ected.

2

To test the theory that an outside radiation caused radioactiv-

ity, Elster and Geitel took their radioactive samples to the bo om

of a mine in the Harz Mountains south of Wolfenbü el. If light

or some other radiation caused radioactivity, surely more than a

half-mile of earth would block some of it. Yet their sample went

on sending out rays at the bo om of the mine just as it had at the

surface.

3

Figure 3-2. Julius Elster (le ) and Hans Geitel (right). Courtesy of Archiv Fricke,

Wolfenbü el.

A NEW SCIENCE

40

Becquerel rays seemed to behave like x rays. Since cathode rays

produce x rays, could they also produce Becquerel rays? Elster and

Geitel bombarded a piece of pitchblende with cathode rays, but its

radiation did not change. Nor did sunlight have an e ect. Over the

years scientists tried to change radioactivity by applying x rays and

radioactive radiations, to no avail.

If radioactivity’s energy did not come from an outside source,

the only alternative was an internal source. Many physicists sus-

pected the atom was a system of charged particles. According to

electrical theory, any disturbance to such a system would create

further disturbances. omson suggested in 1898 that a heavy,

presumably complex atom like uranium might rearrange its parts

and cause radioactivity. A related idea was that the atom’s parts

were constantly moving, and that when they reached a particular

unstable arrangement the atom would disintegrate.

Since they could not in uence radioactivity, Elster and Geitel

also surmised that some change inside the atom must cause it. is

was an important conclusion, but it would be inaccurate to ascribe

a modern interpretation to their words, wri en in 1899 before any-

thing was known of atomic transmutation or nuclear power. Elster

and Geitel envisioned something similar to an unstable chemical

compound converting to a more stable form. Such a transforma-

tion would release energy and alter the atom’s characteristics, as it

would no longer be unstable. is did not mean that atoms of one

element would change into another.

e same year Marie Curie posed a new and prescient possibil-

ity. Evolution was an exciting and controversial topic in the late

nineteenth century. Perhaps, Curie suggested, radioactivity was a

sign that the heavy elements were evolving into di erent forms. In

just a few years two young researchers would con rm her hunch.

RUTHERFORD, SODDY, PARTICLES, AND ALCHEMY?

41

MATERIAL RAYS? DISCOVERY OF

THE BETA PARTICLE

Marie Curie was the rst to suggest in print (January 1899) that

Becquerel rays might be pieces of ma er. omson had shown

in 1897 that the cathode “rays” were actually small negatively

charged particles, which he called “corpuscles.” Scientists even-

tually preferred the term electron, rst suggested in 1891 for the

hypothetical unit of electricity. German physicists Emil Wiechert

and Walter Kaufmann made similar ndings and determined

these particles were only about 1/2000 the mass of the smallest

atom, hydrogen. If cathode rays were particles of ma er, could the

Becquerel rays also be material?

ese scientists had used a common test to distinguish

charged particles from nonmaterial radiation. A magnet can push,

or de ect, moving charged particles from their paths, but has no

e ect on other radiations. e direction a particle moves when

the magnet de ects it depends upon the particle’s electric charge.

Several researchers decided to apply a magnetic force, or eld, to

Becquerel rays.

Elster and Geitel had previously determined that a magnetic

eld could reduce certain electrical e ects in air. ey believed

the magnet moved gas ions away from their measuring equipment,

thus lowering the current recorded. Wondering whether ions pro-

duced by Becquerel rays would behave the same way, Elster and

Geitel tried the experiment with uranium. Uranium’s weak rays

did not produce many ions, so they borrowed a sample of radium

from Friedrich Giesel, who had just demonstrated radium at their

local scienti c society in Brunswick. eir magnet moved the ions

that Giesel’s radium produced.

A NEW SCIENCE

42

But what if, in addition to moving the gas ions, the magnet

de ected the Becquerel rays themselves? Elster and Geitel used a

phosphorescent screen to detect the radium rays, which created

a bright spot on the screen. ey could not move the bright spot

with their magnet. is seemed to show that Becquerel rays were

not material particles, but rather more like x rays.

Giesel decided to check Elster and Geitel’s work. Using a phos-

phorescent screen and photographic plates to record the paths of

rays from radium and from a substance he believed to be polo-

nium, Giesel found (in October 1899) that his magnet did de ect

the rays. e direction of de ection changed when he changed the

orientation of the magnet’s poles. e rays must be material.

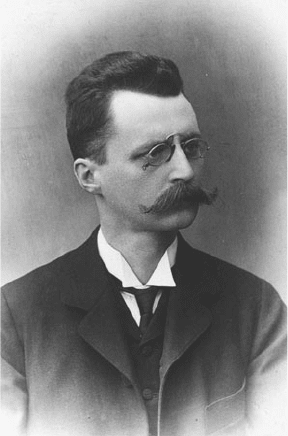

Figure 3-3. Stefan Meyer. Courtesy of the Austrian Central Library for Physics

(Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik).

RUTHERFORD, SODDY, PARTICLES, AND ALCHEMY?

43

Earlier in 1899 Giesel had demonstrated new radioactive mate-

rials at a scienti c meeting in Munich. A young physicist from

the University of Vienna was intrigued. e son of a writer and

art collector, Stefan Meyer came from a distinguished Viennese

middle-class family and grew up in a cultured and liberal-minded

environment (Figure 3-3). Giesel agreed to loan samples to Meyer

for his research on magnetic properties of the elements. Meyer

also procured radium and polonium from the Curies.

Meyer teamed up with his colleague Egon Ri er von Schweidler,

the son of an a orney. Schweidler had been investigating electricity

in gases, which made radioactivity a natural t for his next research

(Figure 3-4). e two physicists decided to examine the electrical

phenomena reported by Elster and Geitel. Unlike Elster and Geitel,

Figure 3-4. Egon Ri er von Schweidler. Courtesy of the Austrian Central Library for

Physics (Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik).

A NEW SCIENCE

44

Meyer and Schweidler were able to de ect Becquerel rays. is

result meant these rays were charged particles. From the direction

of de ection they realized the particles were negatively charged.

Meanwhile in Paris, at the Museum of Natural History, the

discoveries of radium and polonium had revived Becquerel’s

interest in radioactivity. Becquerel obtained samples from the

Curies. A er nding that radium’s rays behaved like x rays inso-

far as re ection, refraction, and polarization were concerned, he

compared the luminescence that Becquerel and x rays produced

on phosphorescent minerals from the museum’s collection. e

results were ambiguous. Sometimes the e ects were quite di er-

ent, which could mean that the Becquerel rays were electromag-

netic radiations of di erent wavelengths from the x rays. On the

other hand, some minerals reacted to radium’s rays very much as

they had to cathode rays in earlier studies by his father, which sug-

gested that Becquerel rays could be material particles.

To see whether x rays or cathode rays were the be er match for

Becquerel rays, Becquerel tested rays from both radium and polo-

nium with an electromagnet. He then published the third paper in

less than six weeks announcing that a magnet de ected the rays.

e Becquerel rays were material, like cathode rays!

But not entirely. Only the more penetrating (beta) rays were

de ected, according to Pierre Curie’s report early in 1900. e

rest of the Becquerel rays seemed to resemble x rays. e other

researchers had not distinguished the alpha and beta rays in their

experiments with magnets. ese rays can be separated by insert-

ing paper or cardboard in the rays’ path, which will absorb the

alphas but allow the betas to pass through.

Since electric forces also can de ect moving charged particles

from their paths, Friedrich Ernst Dorn at Germany’s University of

Halle applied an electric force to radium’s beta rays. e electric

RUTHERFORD, SODDY, PARTICLES, AND ALCHEMY?

45

eld, which would not a ect the path of x rays, bent the path of the

beta rays as expected.

ese results pointed towards a new set of experiments. e

distance a force eld pushes a charged particle from its original

path depends on both its charge and its mass. By sending charged

particles through an arrangement which combines both kinds of

force elds, the ratio between a particle’s charge and mass can be

determined. Becquerel succeeded rst, ge ing values comparable

to the known ratio of charge to mass for cathode ray particles. e

cumulative evidence convinced most scientists that the beta rays

were high speed cathode ray particles.

Rather than defeating the x-ray theory of radioactivity, the

discovery of the beta particle strengthened it. When x rays strike

ma er, they produce secondary rays. Pierre Curie and Sagnac

found that secondary rays carried a negative charge. Apparently,

some of these rays were particles.

e parallels were unmistakable. Some secondary rays were

negatively charged particles. e beta rays were also negatively

charged particles, and identical to the cathode rays. It made sense

to assume that Becquerel rays were a mixture of x rays and high

speed cathode ray particles created by the x rays.

e beta particle’s discovery gave physicists a tool for investi-

gating an important theoretical question. Electromagnetic theory

predicted that a particle’s mass would increase with its velocity.

e increase would be too small to detect with ordinary cathode

rays. Perhaps the high speed beta particles would yield a measur-

able e ect.

In 1902 Walter Kaufmann found that beta particles did increase

in mass as predicted. Some took this as support for the radical idea

that all mass was electrodynamic. Ma er would be simply an illu-

sion created by electricity in motion.

A NEW SCIENCE

46

e discovery also encouraged radical speculations about

radioactivity’s cause. e Curies suggested a “ballistic hypothesis”

for radioactivity in which the radium atom would gradually lose

energy as it ejected negatively charged particles. “ is viewpoint,”

they wrote in 1900, “would lead to the supposition of a mutable

atom.”

4

eir friend Jean Perrin, whose researches had helped ver-

ify omson’s discovery of the electron, proposed a solar system

type of model for the atom in which negatively charged particles

rotated around positively charged “suns” of greater mass. Becquerel

envisioned the atom as an aggregate of omson’s corpuscles and

larger positively charged particles. Yet, none of these theories was

as revolutionary as the actual turn of events, for which we must go

back to Rutherford in Canada.

THORIUM’S RAYS

A er analyzing behaviors of uranium rays, Rutherford wondered

whether rays from other radioactive substances would behave the

same way. While uranium and thorium were commercially avail-

able, radium and polonium were di cult to procure, limiting

choices for most researchers. is restriction was fortuitous for

Rutherford, since thorium’s strange behavior eventually led him to

remarkable ndings.

Rutherford’s colleague at McGill, professor of electrical engi-

neering R. B. Owens, examined rays from thorium oxide, as

Rutherford had done for rays from uranium oxide. Owens noticed

a radiation from thorium that penetrated thin sheets of aluminum

foil. is radiation varied capriciously, but it seemed to depend

upon air movements. Not sure what to make of this radiation but

believing it was particulate, Rutherford called it an “emanation.”

RUTHERFORD, SODDY, PARTICLES, AND ALCHEMY?

47

VANISHING R ADIOACTIV ITY

Meanwhile, a discovery in Germany threatened the assumption

that radioactivity was permanent and unchanging. In August

1899 Giesel reported that polonium lost its activity over time.

Rutherford determined that thorium emanation also lost

activity and set out to measure how fast its radioactivity decreased

by measuring the current that thorium oxide created in air. Using

an electrometer (similar to an electroscope but with a calibrated

scale and a needle to record the current), he found that the cur-

rent decreased exponentially with time. e activity fell to half its

starting value in only one minute! is measure, the time it takes a

substance to lose half its activity, became a standard in radioactiv-

ity. Later it was called the radioactive half life (Figure 3-5).

orium had another surprise in store for Rutherford: Every-

thing the emanation touched became radioactive. is new

radioactivity also weakened with time, but at a di erent rate

from the emanation.

Rutherford rst thought that the thorium emanation “excited”

activity on other substances, in the way that light excites phos-

phorescence. He soon found that the activity behaved more like

a layer of particles than something excited by an agent like light

or magnetism. No ma er what substance was used to collect the

excited activity, it behaved consistently. It was a racted to the neg-

ative electrode, like a material substance, and could be removed

by scrubbing or with strong acids. Careful measurements showed

that the electrical e ects created by the emanation and by the

excited activity were proportional to each other. is suggested a

causal relationship between them.

Rutherford failed to detect any emanation from a radium sam-

ple he received from Elster and Geitel. ( e material probably was