Malley M.C. Radioactivity: A History of a Mysterious Science

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INTRODUCTION

xx

scienti c instruments and techniques to smoke detectors and

luminous watch dials. In chemistry, radioactivity unlocked the

puzzling periodic table of the elements, altering ideas about ele-

ments and expanding the table itself.

Radioactivity provided novel ways for treating cancer and for

understanding physiological processes. It fueled new enterprises

to nd and use radioactive materials for medical, industrial, and

commercial purposes. e search for radioactive materials revealed

their wide distribution and led to the discovery of cosmic rays.

e new science’s political and social rami cations were far-

reaching. Several national research institutes and special labo-

ratories were created to study radioactivity, accelerating the

concentration of scienti c resources, scienti c teamwork, and gov-

ernment in uence on research. e new eld fostered increased

participation of women in physics. Radioactivity introduced unex-

pected health hazards for those who worked with it, whether they

were academic researchers, miners, therapists, or factory workers.

ese problems spawned new organizations and regulatory agen-

cies and contributed to a popular distrust and disillusionment

with science that increased later in the century.

During the late 1920s radioactivity transmuted into nuclear

physics. e elds of particle physics and nuclear chemistry also

have roots in the 1896 discovery. Centralization of resources,

government involvement, and political events intertwined with

nuclear physics to create a matrix for nuclear weapons and nuclear

reactors, which have forever changed the world.

Radioactivity was one of a series of surprises which greeted

scientists at the turn of the century. It followed on the heels of the

1895 discovery of x rays. e previous year a gas had been found

which chemists were unable to combine with other elements.

Named argon, meaning “idle,” it belonged to an entirely new

INTRODUCTION

xxi

family of chemical elements, the inert gases. In 1897 a Dutch phys-

icist detected what became known as the Zeeman e ect, an esoteric

but theoretically signi cant action of magnetism on spectra which

o ered clues to atomic structure. In the same year the rst sub-

atomic particle, the electron, o cially entered physics. e energy

quantum debuted in 1900, special relativity theory in 1905, and

general relativity in 1916. ese innovations revolutionized phys-

ics during the next few decades. Applications of the new physics

transformed society, while that milieu in turn altered the scienti c

enterprise.

e story of radioactivity is interwoven with the history of

modern physics. is book tells radioactivity’s story in that con-

text, from the rst discovery through subsequent startling ndings

and the questions and problems of researchers who grappled with

this mysterious phenomenon. It outlines the rise of related indus-

tries, research institutions, and medical developments. It provides

background on some contributors to the eld and analyzes factors

a ecting radioactivity’s growth and development. Finally, this

book re ects on radioactivity’s links to perennial human ques-

tions, quests, motifs, and themes.

This page intentionally left blank

PART ONE

A NEW SCIENCE

ere are more things on heaven and earth . . .

an are dreamt of in your philosophy.

—Shakespeare, Hamlet, act 1, scene 5

e turn of the twentieth century was full of surprises for physicists.

Amid the unexpected developments, a new science blossomed. By 1919

this eld had matured and physics was changing dramatically, as was

the world outside the laboratory.

This page intentionally left blank

3

1

The Beginnings

e Roentgen Rays, the Roentgen Rays,

What is this craze?

—Photography, 1896

THE SETTING

It was 1895 in Europe. France was embroiled in the notorious

Dreyfus case, a court-martial tainted with anti-Semitism. England,

France, and Italy were staking out claims to parts of Africa,

while across the Atlantic pioneers streamed into the remaining

American Indian territories. e remnants of the ancient Roman

Empire, now reduced to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, simmered

with tribal enmities and socioeconomic tensions among a mixture

of ethnic groups.

A romantic strand was woven into the era’s culture. Fashion

favored owing skirts, lace, and elaborate hats. Art Nouveau was

all the rage, with lamps that resembled trees and other creations

embodying stylized organic forms, while the Russian composer

Tc h a i k ov s k y ’s Swan Lake premiered in St. Petersburg. Genteel

ladies and digni ed and learned men in top hats frequented

elaborate theatrical productions as well as the theaters of the

A NEW SCIENCE

4

supernatural known as séances. Doomsayers and soothsayers and

assorted fringe elements anticipated the change of centuries with

escalating excitement.

If one listened, among the prophets and cranks who watched

for the turn of the century could be heard an undercurrent of wild

expectations, murmurs of ma er transforming into energy, atoms

reduced to vibrations in the ether, the ebb and ow of reality always

changing yet always the same. is was the sound of the river of

the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who taught that reality

was like a river, forever changing yet forever the same. One never,

according to Heraclitus, steps into the same river twice. Nothing

is permanent but change. Now, in the late nineteenth century,

Heraclitus’ philosophy reappeared in modern popular guise, as his

river metaphorically owed through electromagnetic theory and

carried along bits and pieces of scienti c detritus into the teeming

imagination of the expectant public.

In the biological realm, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution

a orded a scheme which made change integral not only to living

things, but to the forms of life themselves. Evolutionary models,

some predating Darwin, were applied to the earth, the solar system,

and the periodic table of the chemical elements, as well as to stud-

ies of culture, society, and politics. Later, the transmutation theory,

which claimed that some elements could change into other elements,

would suggest that radioactivity could be assimilated to this theme.

In physics, electricity and the beautiful and mysterious e ects

which it created in high voltage vacuum tubes were popular elds

for investigation. Nineteenth-century advances in technology

had made it possible to study ma er and electricity in high vac-

uum. ree German instrument makers, Johann H. W. Geissler,

Heinrich Rühmkor , and Hermann J. P. Sprengel, revolutionized

the study of electricity in rare ed gases.

THE BEGINNINGS

5

In 1855 Geissler developed a pump which used mercury

instead of pistons to remove air from containers. He also devised

thin glass tubes with two metal pieces (electrodes) embedded in

the glass that could be connected to an electrical generator. e

electrodes would receive opposite electrical charges, which by

convention scientists labeled “negative” and “positive.” Depending

on the voltage applied from the generator and the amount of air

still in the tube, magical pa erns of dancing light and darkness

would appear in the tubes. ese pa erns, called “vacuum dis-

charges,” signaled the transfer, or discharge, of electricity between

the oppositely charged electrodes.

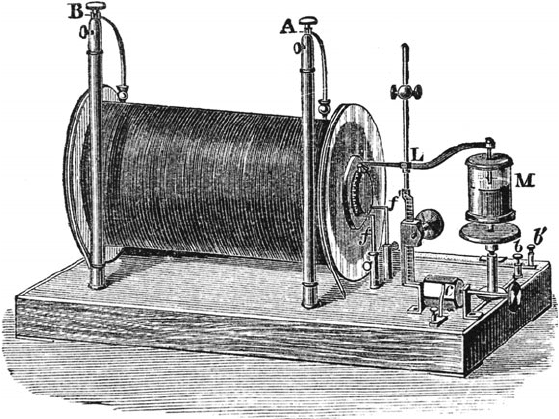

Rühmkor improved the devices (induction coils) that could

generate the high voltages needed to create discharges (Figure 1-1),

Figure 1-1. Rühmkor coil. is device is a transformer for producing high voltages.

From Silvanus P. ompson, Elementary Lessons in Electricity & Magnetism (New York:

Macmillan, 1901), 219.

A NEW SCIENCE

6

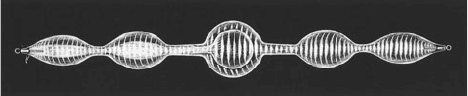

while in 1865 Sprengel modi ed Geissler’s pump. Sprengel’s pump

could remove nearly all of the air from glass tubes designed for this

purpose, called “vacuum tubes.” e e cient pump facilitated

study of the vacuum discharges. ese striking visual displays fas-

cinated physicists, who tried to make sense of their complexity by

grouping the displays into categories and nding the conditions

needed to produce each type (Figure 1-2). Some even imagined

replacing the concept of ma er with evanescent energy forms like

the luminous electrical discharges. e energy forms supposedly

disappeared into and reappeared from a ghostlike invisible uid

called the “universal ether.”

Figure 1-2. Geissler tube. From Henry E. Roscoe, Spectrum Analysis (London: Macmillan,

1869), 106.

THE BEGINNINGS

7

e idea of an invisible uid which pervaded the universe was

not new, but the British physicist James Clerk Maxwell had made it

central to a remarkable mathematical-physical theory. Maxwell’s

theory joined the invisible forces of electricity and magnetism into

a complex known as electromagnetism, and linked electromagne-

tism with light.

Maxwell believed that light was a wave motion in a weightless

uid of electromagnetic origin, the ether. He predicted another

type of wave motion in the ether, later known as radio waves.

Light, radio waves, and other related wave motions became known

as electromagnetic radiations.

Some scientists speculated that ma er might be made of

ether particles. e famed Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleyev

included ether in his revised (1903) periodic table of the ele-

ments. A vocal minority promulgated energetics, a scienti c

philosophy which viewed energy as primary, relegating the

world of our senses, of sights and sounds and smells and myriads

of discrete objects, to a phantom existence as mere energy forms.

e British mathematician James Jeans envisioned oppositely

charged particles annihilating each other in a burst of energy,

presaging later ideas about antima er.

Ma er, the stu we can see and touch, had long been viewed

as the primary reality. Energy was only a manifestation of ma er

in motion, whether of invisible particles, living beings, or machines.

Maxwell’s theory made it possible to compute equivalences between

ma er and energy, implying they could be converted into one

another. From there it was a simple step to stand the traditional view

on its head and make ma er into a form of energy. Perhaps material

objects were merely disturbances in a sea of ether. Most scientists

did not subscribe to this extreme view; but its adherents were out-

spoken, and it was taken up by some members of the general public.