Lee K.K. Lectures on Dynamical Systems, Structural Stability and Their Applications

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

relating

to

local

geometric

properties

in

the

neighborhood

of

points,

lines,

surfaces

or

manifolds

in

general.

In

global

differential

geometry,

by

contrast,

one

is

interested

in

the

integrals

of

those

local

differential

relations

and

questions

arise

whether

those

integrals

exist

and

whether

they

are

unique.

For

lower

dimensional

spaces

(n

~

3)

there

is

a

well

balanced

relationship

between

local

and

global

results

in

differential

geometry

(e.g.,

Gauss-Bonnet

theorem).

However,

for

higher

dimensional

space,

it

is

much

more

difficult

to

generalize

the

local

results

to

global

ones.

In

Newtonian

or

Poincare-invariant

theories

the

space-time

is

considered

to

be

given

a

priori,

and

the

physical

dynamics

are

defined

on

this

background.

In

general

relativity,

the

topological

and

geometric

structure

of

space-time

is

to

be

established

as

part

of

the

dynamics.

Global

structures

place

restrictions

on

the

class

of

differentiable

manifolds

suitable

for

space-times.

Global

structures

are

presented

in

mathematical

form

but

their

imposition

is

usually

based

upon

physical

intuition

and

on

observations.

once

they

are

imposed,

however,

the

resultant

class

of

admissible

spaces

further

clarifies

the

significance

of

any

given

global

structure

and

could

even

lead

to

its

rejection.

Before

getting

into

formal

definitions

and

major

results,

let

us

describe

the

concepts

we

shall

encounter

in

an

intuitive

way.

We

have

defined

the

tangent

space

of

a

manifold

Mat

a

point

p £

M,

i.e.,

MP.

The

tangent

bundle

of

M,

denoted

by

TM,

is

defined

as

the

union

of

all

tangent

spaces

of

M,

i.e.,

TM

= U

~for

all

p £

M.

A

vector

bundle

of

a

manifold

M

is

a

family

of

vector

spaces

V

each

attached

to

a

point

of

M

such

that

locally

the

vector

bundle

is

homeomorphic

to

u x V

where

U

is

a

neighborhood

of

p £

M.

The

principal

bundle

of

M

with

structural

group

G

is

locally

homeomorphic

to

the

attachment

to

each

point

in

M a

different

copy

of

G,

i.e.,

the

bundle

is

locally

homeomorphic

to

U x G

where

U

is

a

neighborhood

of

p £

M.

we

84

say

a

bundle

is

trivial,

we

mean

that

instead

of

the

bundle

space

"is

locally

homeomorphic

to"

by

"is

homeomorphic

to".

In

the

following,

we

shall

discuss

fiber

bundles

on

a

smooth

manifold

with

smooth

mappings.

These

notions

are

very

useful

for

our

discussion

as

well

as

for

differential

geometry.

But

it

should

be

pointed

out

that

fiber

bundles

can

be

defined

on

topological

manifolds

only

with

all

maps

continuous

[Steenrod

1951].

For

example,

let

B,

X

and

F

are

topological

manifolds

and

let

a

continuous

map

~

: B

~

X

of

B

onto

X

called

the

projection

and

B

be

the

bundle

space

and

X

the

base

space.

The

B

is

a

fiber

bundle

over

X

with

fiber

F,

and

projection

~

if

for

every

p E

X,

~-

1

(p)

is

homeomorphic

to

F,

and

there

exists

a

neighborhood

U

of

p

and

a

homeomorphism

¢u :

Bu

~

UxF

where

Bu

=

~-

1

(U)

such

that

the

following

diagram

commutes

¢u

where

~u

is

an

obvious

projection.

X F

.1.

~u

u

A

c-

principal

fiber

bundle

is

a

set

(B,

M,

G)

where

B,

M

are

c-

manifolds,

G a

Lie

group

(i)

G

acts

freely

(and

c-)

to

the

right

on

B,

i.e.,

B

X G

~

B

defined

by

(b,g)

~

bg

= R

9

b E B

where

b E

B,

g E

G.

(ii)

M

is

the

quotient

space

of

B

by

equivalence

under

G

and

the

projection

~

: B

~

M

is

c-,

so

for

p e

M,

G

is

simply

transitive

on

~-

1

(p)

where

~-

1

(p)

is

a

fiber

over

p e

M.

(iii)

B

is

locally

trivial,

i.e.,

for

any

p

eM,

there

is

a

neighborhood

U

of

p

and

c-

map

Fu

:

~-

1

(U)

~

G

such

that

Fu

commutes

with

R

9

for

every

g e G

and

the

map

of

~-

1

(U)

~

UxG

given

by

b

~

(~(b),Fu(b))

is

a

diffeomorphism.

Here

B

is

called

the

bundle

space,

M

the

base

space,

and

G

the

structural

group.

Note,

the

fibers

~-

1

(p)

are

diffeomorphic

toG

in

a

special

way,

i.e.,

via

the

map

b : G

~

~-

1

(~(p))

c

B

defined

by

b(g)=

R

9

b.

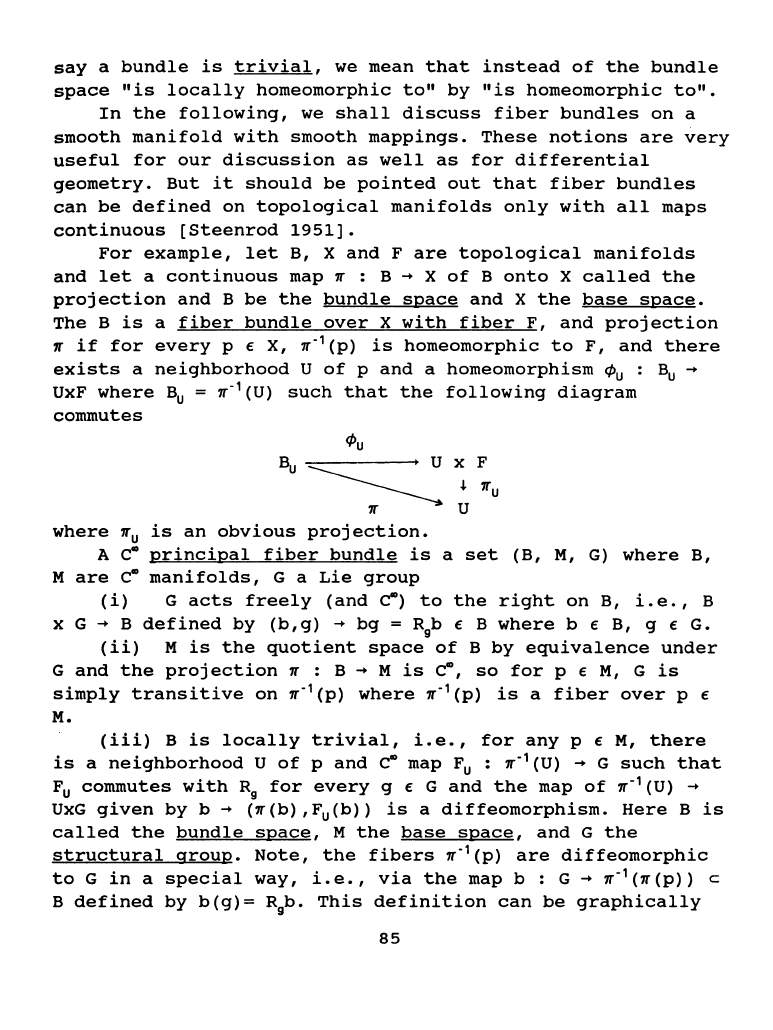

This

definition

can

be

graphically

85

illustrated

by

the

following

figure

(Fig.2.7.1).

B

G

Fig.2.7.1

As

before,

G a

Lie

group,

M a

manifold,

then

B = M X G

provided

with

the

right

action

of

G

on

itself

in

the

second

factor,

i.e.,

(p,g)h

=

(p,gh),

is

the

bundle

space

of

a

principal

bundle

which

is

called

the

trivial

bundle.

A

cross-section

of

a

bundle

is

a

continuous

map s : M

~

B

such

that

r·s

=

id

on

M

(i.e.,

r(s(p))

= p

for

all

p

eM).

Let

us

discuss

some

examples

of

bundles:

(i)

From

the

above

pictorial

representation

of

a

fiber

bundle,

we

can

let

the

base

space

be

s

1

,

the

fiber

being

a

line

segment

[0,1],

and

the

bundle

space

being

s

1

x

[0,1].

Clearly,

this

bundle

is

a

trivial

bundle.

(ii)

For

a

flexible

rectangular

sheet,

we

hold

one

side

of

the

sheet

fixed

and

twist

the

other

side

through

1so•

and

then

identify

(glue

together)

these

two

opposing

sides.

Then

the

resulting

two-dimensional

space

is

a

bundle

space,

and

is

the

well-known

Mobius

band.

The

base

space

is

the

circle

(S

1

),

the

fiber

is

a

line

segment

[0,1],

and

the

group

action

is

the

"twist"

(Z

2

).

Aside

from

the

"seam",

it

is

clear

that

the

inverse

of

the

projection

map

of

a

neighborhood

of

a

point

on

the

circle

is

a

small

rectangle

(i.e.,

locally

a

product

bundle).

But

clearly,

86

this

fiber

bundle

is

not

a

trivial

bundle.

Theorem

2.7.1

A

bundle

is

isomorphic

(or

homeomorphic)

to

a

trivial

bundle

iff

there

is

a

c-

(or

continuous)

cross-section.

The

above

theorem

means

that

a

trivial

bundle

has

global

cross-sections.

The

two

simple

examples

illustrate

exactly

this

point.

Both

bundles

have

local

cross-sections,

but

only

the

first

one

has

a

global

cross-section.

By

the

way,

the

global

cross-

section,

if

it

exists,

is

homeomorphic

to

the

base

space.

Let~

be

a

c-

manifold,

B

be

the

set

of

(m+1)-tuples

(p,e

1

,

••

,em),

where

p E

M,

and

{e

1

,

••

,em}

is

a

basis

of

MP,

and

let~:

B

~

M

be

defined

by

~(p,e

1

,

••

,em)

=

p.

Let

g e

GL(m,R) =

G,

then

GL(m,R)

acts

to

the

right

on

B

by

R

9

(p,e

1

,

••

,em) =

(p,

~

g;

1

ei'

•.

,

~

gime;)

where

g

is

viewed

as

a

matrix

g

=(g;j).

Let

(x

1

,

••

,xm)

be

a

coordinate

system

defined

in

a

neighborhood

U

of

p,

Then

Fu

is

defined

by

letting

Fu(P',f

1

,

••

,fm) =

(dxi(f;))

=

(g;j)

E

GL(m,R),

where

p'

e U.

Using

the

c-

structure

given

to

B

by

the

local

product

representation

(~,Fu),

we

see

that

B

is

the

bundle

space

of

a

principal

bundle,

called

the

bundle

of

bases

of

M,

B(M).

For

a

classical

notion

of

fiber

bundles

or

tangent

bundles

one

can

find

in

Anslander

and

MacKenzie

[1963].

It

is

also

convenient

at

times

to

view

B

as

the

set

of

nonsingular

linear

transformations

of

Rm

into

the

tangent

spaces

of

M,

i.e.,

we

identify

b =

(p,e

1

,

••

,em)

with

the

map

b :

(r,

••

,

rm)

~

~r;e;.

If

this

is

done,

it

is

natural

to

consider

GL(m,R)

as

the

nonsingular

linear

transformations

of

Rm,

where

bg

(r

1

,

••

,

rm)

=

~i.irigiiei

=

~i

(~;r;gji)

ei

b(g(r

1

,

••

,rm)).

In

other

words,

bg

(as

a map) = b

(as

a

map)·g.

If

G

is

a

Lie

group,

H a

closed

subgroup,

then

there

is

a

principal

bundle

with

base

space

G/H

(left

cosets),

bundle

space

G,

and

the

structure

group

H

such

that

~=

G

~

G/H

is

the

projection

and

right

action

is

given

by

(g,h)

~

gh.

Thus

a

homogeneous

space

is

an

example

of

a

principal

fiber

87

bundle.

[Helgason

1962,

Steenrod

1951].

Let

(B,M,G)

be

a

principal

bundle

and

let

F

be

a

manifold

on

which

G

acts

to

the

left.

The

fiber

bundle

associated

to

CB.M.Gl

with

fiber

F

is

defined

as

follows:

Let

P

1

= B x

F,

andconsider

the

right

action

of

G

on

P

1

by

(b,f)g

=

(bg,g"

1

f)

where

b E

8,

f E

F,

g E G.

Let

P = P

1

/G,

the

quotient

space

under

equivalence

by

G,

then

P

is

the

bundle

space

of

the

associated

bundle.

The

projection

~

1

:

P

~

M

is

defined

by

~

1

((b,f)G)

=~(b).

For

p

eM,

we

take

a

neighborhood

U

of

p

as

in

(iii)

of

the

definition

of

a

principal

bundle,

with

Fu:

~-

1

(U)

~

G.

Likewise

we

have

Fu

1

:

~

1

(U)

~

F

by

Fu

1

((b,f)G)

=

Fu(b)f

so

that

(~

1

)"

1

(U)

is

homeomorphic

to

U x

F,

and

define

P

as

a

manifold

by

requiring

these

homeomorphisms

to

be

diffeomorphisms.

Thus

~~

and

the

projection

~=

P

1

~

P

are

CO.

First

of

all,

(B,M,G)

as

above,

let

G

act

on

itself

by

left

translation,

then

(B,M,G)

is

the

bundle

associated

to

itself

with

fiber

G.

Let

us

look

at

a

tangent

bundle

as

a

bundle

associated

to

the

bundle

of

basis

B(M)

with

fiber

Rm.

Since

GL(m,R)

is

the

group

of

nonsingular

linear

transformations

of

Rm,

and

hence

act

on

Rm

to

the

left.

The

bundle

space

of

the

associated

bundle

with

fiber

Rm

is

denoted

by

TM

and

it

is

called

the

tangent

bundle

of

M.

TM

can

be

identified

with

the

space

of

all

pairs

(p,t)

where

p e

M,

t e

MP

as

follows:

((p,e

1

,

••

,em),(r

1

,

••

,rm))GL(m,R)

~

(p,

:E

r;e;)·

Hence

the

fiber

of

TM

above

p e M may

be

viewed

as

the

linear

space

of

tangents

at

p,

i.e.,

MP,

and

TM

as

the

union

of

all

the

tangent

spaces

together

with

a

manifold

structure.

Moreover,

the

coordinates

of

TM

can

easily

be

adopted

by

letting

U

be

a

coordinate

neighborhood

in

M

with

coordinates

x

1

,

••

,

~-

Define

coordinates

y

1

,

••

,

Yzm

on

(~

1

) "

1

(U)

in

such

a way

that

if

(p,

t)

e

(~

1

) "

1

(U)

,

then

Y;(p,t)

=

X;(P),

Y.,.;(p,t)

=

dx;(t)

where

i =

1,

•.

,m.

Clearly,

a

CO

vector

field

may

be

regarded

as

a

cross-

section

of~~.

For

more

on

tangent

bundles

see

[Bishop

and

Crittenden

1964,

Yano

and

Ishihara

1973,

and

other

modern

differential

88

geometry

books].

It

is

interesting

to

note

the

following

theorem.

Theorem

2.7.2

TM

is

orientable

even

if

M

is

not.

When

Rm,

in

the

tangent

bundle

of

M,

is

replaced

by

a

vector

space

constructed

from

Rm

via

multilinear

algebra,

i.e.,

the

tensor

product

of

Rm

and

its

dual

with

various

multiplicities,

we

get

a

tensor

bundle.

A

cross-section

which

is

ca

on

an

open

set

is

called

a

ca

tensor

field,

and

the

type

is

given

according

to

the

number

of

times

Rm

and

its

dual

occur.

The

structural

group

of

a

tensor

bundle

is,

of

course,_

GL(m,R)

and

it

acts

on

each

factor

of

the

tensor

product

independently.

GL(m,R)

acts

on

Rm

as

with

the

tangent

bundle,

and

it

acts

on

the

dual

via

the

transpose

of

the

inverse,

i.e.,

if

v £

R~

=the

dual

of

Rm,

x £

Rm,

g £

GL(m,R),

then

gv(x)

=

v(g-

1

x).

Clearly,

TM

is

a

special

case

of

a

tensor

bundle;

this

is

similar

to

that

a

tangent

vector

is

a

special

tensor,

a

contravariant

tensor

of

rank

one.

Vector

bundles,

which

we

shall

encounter

later,

in

which

the

fiber

is

a

vector

space

and

they

are

frequently

defined

with

no

explicit

mention

made

of

the

structural

group

(although

often

it

is

a

subgroup

of

the

general

linear

group

of

the

vector

space).

It

is

usually

defined

as

the

union

of

vector

spaces,

all

of

the

same

dimension,

each

associated

to

an

element

of

the

base

space

and

defining

the

manifold

structure

via

smooth,

linearly

independent

cross-sections

over

a

covering

system

of

coordinate

neighborhoods.

In

fact,

we

did

this

for

TM,

a

special

case

of

a

vector

bundle.

The

quotient

space

bundle

of

an

imbedding,

sometimes

considered

as

a

normal

bundle

for

Riemannian

manifold,

may

be

defined

as

follows:

Let

i:

N

~

M

be

the

imbedding

of

the

submanifold

N

in

M.

The

fiber

over

q £ N

is

the

quotient

space

Mi<ql/di

(Nq)

,

and

the

bundle

space

is

the

union

of

these

fibers,

so

the

bundle

space

can

be

considered

as

the

collection

of

pairs

(q,t+di(Nq)),

where

t £

M;cql"

The

Whitney

Cor

direct>

sum

of

two

bundles

~

(B,M,G,~,F)

and

C

(B',M,G',~',F')

over

the

same

base

space

M

is

the

bundle~

e C

whose

fiber

over

x £ M

is

Fe

F'.

If

89

¢,

t

are

charts

for

~'

C

over

U

respectively,

a

chart

p

for

~

$ C

over

U

is

Px

=

¢x

$

fx

: F +

F'

~

Rm

$ R".

Thus

dim(~

$

{)

=dim

B

+dim

B'.

Let

two

bundles

~

and

C

over

the

same

base

space

M

with

B c

B',

then~

is

a

sub-bundle

of

C

if

each

fiber

F

is

a

sub-vector-space

of

the

corresponding

F'.

Lemma

2.7.3

Let

~

and

C

be

sub-bundle

of

~

such

that

each

vector

space

F(~),

fiber

of~'

is

equal

to

the

direct

sum

of

the

subspaces

F amd

F'.

Then~

is

isomorphic

to

the

Whitney

sum~

$

{.

Then

the

question

arises,

given

a

sub-bundle

~

c

~

does

there

exist

a

complementary

sub-bundle

so

that

~

splits

as

a

Whitney

sum?

If

~

is

provided

with

a

Euclidean

metric

(provided

the

base

space

is

paracompact)

then

such

a

complementary

summand

can

be

constructed

by

letting

F(~~)

be

the

subspace

of

F(~)

consisting

of

all

vectors

v

such

that

v·w

= 0

for

all

we

F(~).

Let

B(~~)

c

B(~)

be

the

union

of

all

F(~~).

One

can

show

that

B(~~)

is

the

total

space

of

a

sub-bundle

~~

c

~·

Moreover,

~

is

isomorphic

to

the

Whitney

sum~$

C~

[Milnor

and

Stasheff

1974].

Here~~

is

called

the

orthogonal

complement

of

E

in

~·

Suppose

N c M

are

smooth

manifolds

and

M

is

provided

with

a

Riemannian

matric.

Then

the

tangent

bundle

TN

is

a

sub-bundle

of

the

restriction

TMIN.

Then

the

orthogonal

complement

TN~

c

TMIN

is

the

normal

bundle

of

N

in

M,

i.e.,

~(N)=

{(q,t)

E

TMit

E

Mq

for

some

q

EN

and

t

~

Nq}•

We

would

like

to

mention

that

the

notion

of

a

normal

bundle

is

not

only

useful

in

differential

geometry

(such

as

in

discussing

geodesics

and

completeness

of

the

Riemannian

manifold)

but

also

very

useful

in

algebraic

and

differential

topology

(such

as

using

the

Whitney

duality

theorem

to

relate

the

immersibility

of

an-dim

manifold

in

R~k).

Interested

readers

may

want

to

consult

the

following

books:

Steenrod

(1951],

Milnor

and

Stasheff

(1974].

Now

let

us

get

back

to

some

properties

of

tangent

bundles.

Theorem

2.7.4

[Steenrod

1951]

The

tangent

bundle

to

a

differentiable

manifold

admits

a

nonzero

cross-section

and

90

is

equivalent

to

the

existence

of

a

nowhere

zero

vector

field

on

M

iff

the

Euler

characteristic

of

M

is

zero.

As

we

have

defined

earlier,

the

Euler

characteristic

of

a

manifold

M

is

defined

in

Section

2.5.

For

example,

we

have

pointed

out

that

(i)

for

a

noncompact

manifold,

its

Euler

characteristic

vanishes;

(ii)

for

compact

manifolds,

only

odd

dimensional

ones

have

a

vanishing

Euler

characteristic.

Thus,

only

odd

dimensional

spheres

have

a

nowhere

zero

vector

field.

One

can

convince

oneself

that

there

does

not

exist

a

nowhere

zero

tangent

vector

on

2-dim

sphere.

Milnor

(1965]

gives

an

interesting

and

illuminating

view

on

this.

When

~

is

homeomorphic

to

~

X

Rm,

it

is

a

trivial

bundle.

In

such

a

case,

one

says

that

the

manifold

has

a

trivial

tangent

bundle,

or

the

manifold

is

parallelizable.

Although

all

odd-dimensional

spheres

have

a

nowhere

zero

vector

field,

but

it

is

a

deep

result

(Bott

and

Milnor

1958,

Adams

1962]

that

only

S

1

,

s

3

,

and

S

7

have

trivial

tangent

bundle

(i.e.,

they

are

the

only

parallelizable

n-spheres).

Normally,

some

heavy

machinery

in

algebraic

topology

such

as

characteristic

classes

(e.g.,

Milnor

and

Stasheff

1974,

Steenrod

1951,

Husemoller

1975]

and

obstructions

(e.g.,

Milnor

and

Stasheff

1974,

Steenrod

1951]

are

needed

to

prove

the

following

theorem.

We

shall

relate

the

historical

origin

of

the

term

parallelizable

manifold

with

a

non-zero

vector

field.

Let

us

assume

M

is

parallelizable,

i.e.,

TM

= M x

Rm.

Thus

M

has

m

linearly

independent

tangent

vector

fields

ti(p)

=

(p,(0,

••

,1,

••

,o))

with

1

in

the

ith

place,

for

any

p £

M.

In

other

words,

at

any

point

them

vectors

ti(p)

are

a

basis

for

~-

1

(p)

c

TM.

Thus,

a

nonzero

vector

v f

~-

1

(p)

can

be

expressed

by

v =

~

aiti(p),

then

one

can

transport

it

parallel

to

itself

over

the

entire

manifold

to

obtain

a

nowhere

zero

vector

field

by

setting

v(p)

=

~

aiti(p)

for

all

p f

M.

This

is

the

global

notion

of

parallel

transport

in

such

a

manifold.

From

the

above

demonstration,

it

is

almost

trivial

that

if

M

is

parallelizable,

it

has

a

global

~

base

field.

91

Theorem

2.7.5

A

manifold

~

is

said

to

be

parallelizable,

(i.e.,

has

a

trivial

tangent

bundle

TM

= M x

Rm)

iff

M

admits

a

global~

base

vector

field

[e.g.,

Milnor

and

Stasheff

1974].

Theorem

2.7.6

(generalization

of

a

theorem

due

to

Cartan)

Any

connected

Lie

group

G

is

topologically

a

product

space

H X E

where

H

is

a

compact

subgroup

of

G

and

E

is

a

Euclidean

space.

E.g.,

In

physics,

the

proper

Lorentz

group

L

0

,

or

S0(3,1),

~

S0(3)

x R

3

,

and

its

universal

covering

group

SL(2,C)

~

s

3

X R

3

•

If

(B,M,G)

is

a

principal

bundle,

H a

subgroup

of

G,

then

G

is

reducible

to

H

iff

there

exists

a

principal

bundle

(B',M,H)

which

admits

a

bundle

map

f:

(B',M,H)

~

(B,M,G)

such

that

fM

is

the

identity

map

on

M,

f

8

is

one-to-one,

and

fG

is

the

inclusion

map

H

c~

G.

Theorem

2.7.7

[Steenrod

1951]

If

(B,M,G)

is

a

principal

bundle,

H a

maximal

compact

subgroup

of

G,

then

G

can

be

reduced

to

a

bundle

with

structure

group

H.

Corollary

2.7.8

Every

principal

bundle

with

GL(m,R)

as

the

structure

group,

e.g.,

bundle

of

bases

B(M),

can

be

reduced

to

a

bundle

with

the

structural

group

being

the

orthogonal

group

O(m).

The

reduced

bundle

with

O(m)

as

structural

group

is

called

the

bundle

of

orthonormal

bases

and

denoted

by

O(M).

Many

modern

differential

geometry

books

have

at

least

one

or

two

chapters

covering

fiber

bundles.

For

instance,

Bishop

and

Crittenden

[1964],

Helgason

[1962],

Kobayashi

and

Nomizu

[1963].

For

specific

details

in

tangent

and

cotangent

bundles,

see

Yano

and

Ishihara

[1973].

For

more

advanced

readers,

the

classic

by

Steenrod

[1951]

is

highly

recommended.

For

a

more

modern

and

broader

treatment,

Husemoller

[1975]

is

also

recommended.

2.8

Differential

forms

and

exterior

algebra

Tensor

analysis

is

part

of

the

usual

mathematical

92

repertoire

of

a

physicist

or

engineer.

Differential

forms

are

special

types

of

tensors.

Yet,

its

utility

and

conceptual

implications

are

far

beyond

the

capabilities

of

tensors.

Not

only

does

it

provide

more

compact

formulations

of

electrodynamics,

Hamiltonian

mechanics,

etc.

and

simpler

mathematical

manipulations,

but

it

also

provides

topological

implications.

In

this

section,

we

shall

briefly

define

and

discuss

some

properties

of

differential

forms

and

exterior

algebra,

and

illustrate

its

power.

It

is

very

tempting

to

briefly

discuss

de

Rham

cohomology

theorem.

Once

again,

the

reader

is

urged

to

consult

those

differential

geometry

books

we

have

just

mentioned

earlier

for

further

details.

For

p £

M,

the

dual

vector

space

M;

of

MP

is

called

the

cotangent

space

(or

the

space

of

covectors

at

p).

An

assignment

of

a

covector

at

each

p

is

called

a

one-form.

If

(u

1

,

••

,u")

is

a

local

coordinate

system

in

a

neighborhood

of

p,

then

du

1

,

••

,du"

form

a

basis

forM;,

and

they

are

the

dual

basis

of

the

basis

a;au

1

,

•••

,

a;au"

of~·

So

in

a

coordinate

neighborhood,

a

1-

form

can

be

written

as

a =

Ei

fidui.

Clearly,

a

is~.

if

fi's

are.

Note,

one-form

can

also

be

defined

as

an

F(M)

linear

mapping

of

the

F(M)-module

X(M)

into

F(M).

That

is,

(a(X))P=

<aP,

XP>,

where

X£

X(M), p £

M.

The

exterior

product

is

defined

by

A A B =

(A

x

B)

8

,

here

a

denotes

that

it

is

antisymmetrized,

where

A

and

B

are

skew-symmetric,

covariant

tensors.

It

has

the

following

properties:

(a)

associativity:

(A

A

B)

A C

=A

A

(B

A

C),

(b)

distributivity:

(A

+

B)

A C = A A C + B A C,

(c)

anticommutativity:

If

A

is

of

degree

p,

and

B

is

of

degree

q,

then

A A B =

(-1)~B

A A.

Of

course,

together

with

addition

and

scalar

multiplication

operations

they

form

the

algebra.

An

r-form

can

be

defined

as

a

skew-symmetric

r-linear

mapping

over

F(M)

of

X(M)x

•.•

xX(M)

(r-times)

into

F(M).

If

a

1

,

••

,ar

are

1-forms,

X

1

,

••

,Xr £ X(M),

then

(a

1

A a

2

A

...

A

ar)

(X

1

,

••

,Xr)

93