Lee K.K. Lectures on Dynamical Systems, Structural Stability and Their Applications

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

i.e.,

the

Jacobian

of

the

inverse

mapping

is

the

reciprocal

of

the

Jacobian

of

the

mapping.

Corollary

2.4.10

(Inverse

Function

Theorem

for

Manifolds).

If

p

EM,~

is

a

CU

map

from

M

~

N,

then~

is

a

diffeomorphism

of

an

open

neighborhood

of

p

onto

an

open

neighborhood

of

~(p)

iff

d~

is

an

isomorphism

onto

at

p.

In

defining

arcwise

connectedness,

we

have

defined

a

path

as

a

mapping.

Likewise

in

these

notes,

curves

will

also

be

viewed

as

a

special

case

of

mappings.

In

particular,

we

will

deal

almost

exclusively

with

parameterized

curves,

in

particular,

we

shall

discuss

the

various

trajectories

and

orbits

in

the

phase

space

of

a

dynamical

system.

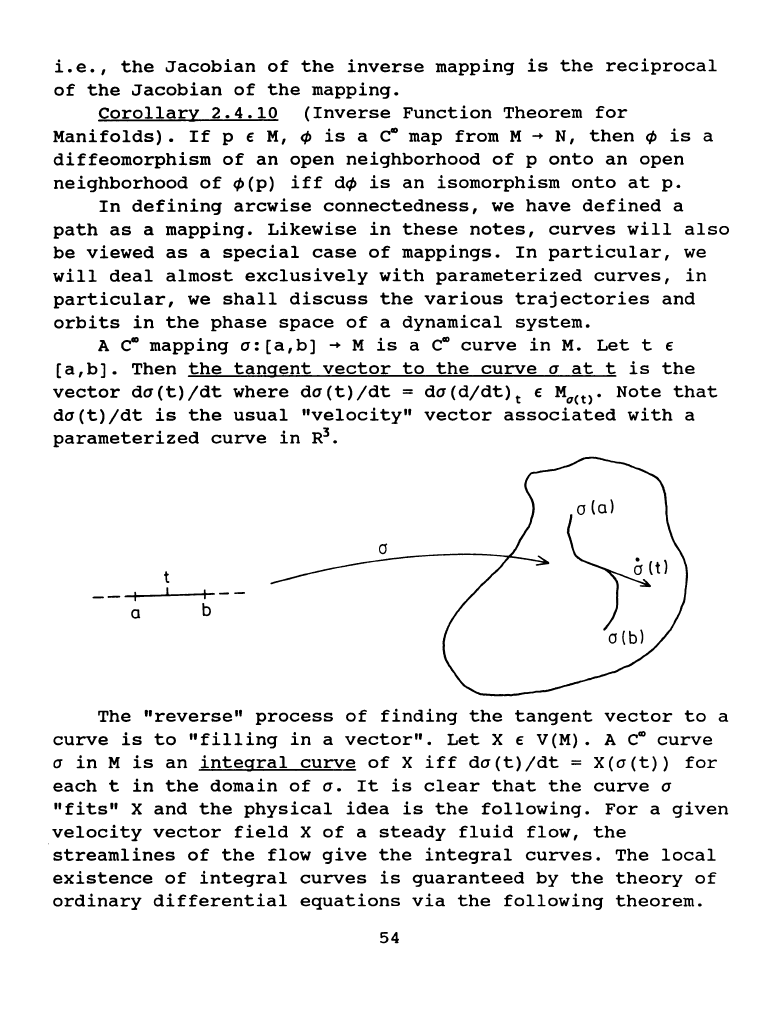

A

CU

mapping

a:

[a,b]

~

M

is

a

CU

curve

in

M.

Let

t E

[a,b].

Then

the

tangent

vector

to

the

curve

a

at

tis

the

vector

da

(t)

/dt

where

da

(t)

/dt

=

da

(d/dt)

t E

Ma<t>.

Note

that

da(t)/dt

is

the

usual

"velocity"

vector

associated

with

a

parameterized

curve

in

R

3

•

t

~tl

a(bl

a

b

The

"reverse"

process

of

finding

the

tangent

vector

to

a

curve

is

to

"filling

in

a

vector".

Let

X E V(M). A

CU

curve

a

in

M

is

an

integral

curve

of

X

iff

da(t)/dt

=

X(a(t))

for

each

t

in

the

domain

of

a.

It

is

clear

that

the

curve

a

"fits"

X

and

the

physical

idea

is

the

following.

For

a

given

velocity

vector

field

X

of

a

steady

fluid

flow,

the

streamlines

of

the

flow

give

the

integral

curves.

The

local

existence

of

integral

curves

is

guaranteed

by

the

theory

of

ordinary

differential

equations

via

the

following

theorem.

54

Theorem

2.4.11

Let

X f V(M)

and

let

p

be

a

point

in

the

domain

of

X.

Then

for

any

real

number

a

there

exists

a

real

number

r > 0

and

a

unique

curve

a:(a-r,

a+r)

~

M

such

that

a(a)

=

p,

and

a

is

an

integral

curve

of

X.

As

we

shall

see,

dynamical

systems

are

often

governed

by

the

type

of

equations

for

integral

curves,

i.e.,

da(t)jdt

=

X(a(T)).

An

integral

curve

is

called

a

trajectory

or

orbit

of

the

system.

We

shall

come

to

these

again

later.

It

is

also

convenient

to

define

a

broken

CD

curve

a

on

an

interval

[a,b)

to

be

a

continuous

map

a

from

[a,b)

into

M

which

is

~

on

each

of

a

finite

number

of

subintervals

[a,

b

1

) , [ b

1

, b

2

) ,

••

, [

bk_

1

,

b]

.

Let

X f

V(M),

we

associate

with

X a

local

one-parameter

group

of

transformations

T,

which

for

every

p f M

and

t € R

sufficiently

close

to¢

assigns

the

points

T(p,t)=

a(t)

where

a

is

the

integral

curve

of

X

starting

at

p.

Theorem

2.4.11

tells

us

that

for

every

p

there

is

a

positive

number

r

and

a

neighborhood

U

of

p

such

that

T

is

defined

and

CD

on

Ux(-r,r).

From

our

notation,

since

the

real

numbers

used

as

the

second

variable

of

T,

are

parameter

value

along

a

curve,

they

must

satisfy

additive

property,

that

is:

if

q E U,

t,

s,

s+t

€

(-r,r)

then

T(T(q,t),s)

=

T(q,s+t).

The

set

of

pairs

(p,t),

p f

M,

t f

I,

is

an

open

subset

of

MxR

containing

p,

hence

a

smooth

manifold

~x

of

dimension

m+1.

The

mapping

a:

~x

~

M

by

(p,t)

~

a(t)

is

the

flow

of

X.

Since

M

and

X

are

~,

so

the

flow

is

also

CD.

Let

us

look

at

this

description

in

terms

of

fluid

flow

again.

As

before,

let

us

suppose

that

the

fluid

is

steady

state,

i.e.,

the

velocity

of

the

fluid

at

each

point

p € M

is

independent

of

time

and

equal

to

the

value

X(p)

of

the

vector

field.

In

this

case,

the

integral

curves

of

X(p)

are

the

paths

followed

by

the

particles

of

the

fluid.

Now

let

¢(p,t)

be

the

point

of

M

reached

at

time

t

by

a

particle

of

the

fluid

which

leaves

pat

time

o.

We

notice

that

¢(p,O)

is

always

p.

Since

velocity

is

independent

of

time,

¢(q,s)

is

the

point

reached

at

time

s+t

by

particle

starting

at

q

at

timet.

If

we

put

q =

¢(p,t),

so

the

particle

started

from

55

the

point

p

at

time

o,

we

can

conclude

that

~(~(p,t),s)

=

~(p,s+t).

Also,

the

smoothness

of~.

as

functions

of

p

and

t,

will

be

influenced

by

the

smoothness

of

X.

A

p-dimensional

distribution

on

a

manifold

M

(p

S

dim

M)

is

a

function

D

defined

on

M

which

assigns

to

each

m e M a

p-

dimensional

linear

subspace

D(m)

of

~·

A

p-dimensional

distribution

D

on

M

is

of

class

c-

at

m e M

if

there

are

c-

vector

fields

X

1

,

•••

,

XP

defined

in

a

neighborhood

U

of

m

and

such

that

for

every

n e U, X

1

(n),

•••

, XP(n)

span

D(n).

An

integral

manifold

N

of

D

is

a

submanifold

of

M

such

that

di(N")

=

D(i(n))

for

every

n

eN.

We

say

that

a

vector

field

X

belongs

to

the

distribution

D

and

write

X e

D,

if

for

every

min

the

domain

of

X,

X(m)

e D(m). A

distribution

Dis

involutive

if

for

all

c-

vector

fields

X,

Y

which

belong

to

D,

we

have

[X,Y] e

D.

A

distribution

D

is

integrable

if

for

every

m e M

there

is

an

integral

manifold

of

D

contaning

m.

It

is

easy

to

see

that

an

integrable

c-

distribution

is

involutive.

Clearly,

every

one-

dimensional

c-

distribution

is

both

involutive

and

integrable,

by

the

existence

of

integral

curves.

We

would

like

to

mention

the

classical

theorem

of

Frobenius:

Theorem

2.4.11

A

c-

involutive

distribution

Don

M

is

integrable.

Furthermore,

through

every

m e M

there

passes

a

unique

maximal

connected

integral

manifold

of

D

and

every

other

connected

integral

manifold

containing

m

is

an

open

submanifold

of

this

maximal

one.

The

following

local

theorem

gives

more

information

as

to

how

the

integral

manifolds

are

situated

with

respect

to

each

other:

Theorem

2.4.12

If

D

is

a

c-

involutive

distribution

on

M,

and

me

M,

then

there

is

a

coordinate

system

(x

1

,

•••

,

xd)

on

a

neighborhood

of

m,

such

that

X;(m) = 0

and

for

every

m'

in

the

coordinate

neighborhood

the

slice

{p

e

Ml

X;(P) =

X;(m')

for

every

i

>dim

D}

is

an

integral

manifold

of

D,

when

given

the

obvious

manifold

structure

induced

by

the

coordinate

map.

56

Before

we

take

off

from

the

concept

of

flow

to

the

basic

idea

of

dynamical

systems

and

structural

stability,

we

should

prepare

ourselves

with

more

conceptual

notions

and

tools

in

differential

geometry

so

that

when

we

are

facing

the

geometric

theory

of

differential

equations,

which

is

an

integral

part

of

dynamical

systems

as

we

have

pointed

out

earlier,

we

will

be

ready

for

it.

There

are

several

topics

we

would

like

to

briefly

discuss,

namely

critical

values,

Morse

Lemma,

groups

and

group

action

on

spaces,

fiber

bundles

and

jets,

and

differential

operators

on

manifolds.

These

last

two

subjects

will

be

discussed

in

Chapter

3.

2.5

Critical

points,

Morse

theory,

and

transversality

The

idea

of

critical

points

to

be

introduced

here

is

an

extension

of

the

concept

of

maxima

and

minima

of

a

function.

As

we

know

in

calculus,

if

a

differentiable

function

f

of

one

variable

x

has

a maximum

of

minimum

for

x = x

0

,

then

dfjdx

= o

at

x

0

•

Similarly,

if

a

function

of

two

variables

x,

y

has

a maximum

or

minimum

at

(x

0

,

y

0

),

then

af;ax

=

af;ay

= o

at

this

point.

Geometrically,

what

we

are

saying

is

that

the

tangent

plane

to

the

surface

z =

f(x,y)

is

horizontal

at

(x

0

,

y

0

).

Of

course

the

same

condition

is

also

satisfied

at

a

saddle

point,

a

point

that

behaves

like

a

maximum when

approached

in

one

way

and

like

a minimum when

approached

in

another.

Moreover,

this

situation

can

be

thought

of

as

corresponding

to

an

embedding

of

M

in

3-space

such

that

the

function

f

is

identified

with

one

of

the

coordinates

z,

and

the

horizontal

plane

z =

f(x

0

,

y

0

)

is

a

tangent

plane

toM

at

(X

0

,

y

0

,

f(x

0

,y

0

)).

More

precisely,

we

have

the

following

definitions.

Let

~.

N"

are

em-manifolds,

and

f

is

a

em

map. A

point

a E

~is

a

critical

point

off

if

df

8

= o,

(i.e.,

df

is

not

onto

at

a,

or

the

Jacobian

matrix

representing

df

has

rank

less

than

the

maximum

(n)).

beN"

is

a

critical

value,

if

b

=

f(a)

for

a E

~-

A

value

b

is

a

regular

value

if

f-

1

(b)

contains

no

critical

points.

Thus

f maps

the

set

of

critical

points

onto

the

set

of

critical

values.

57

For

example,

if

M = N = R

1

,

then

a

critical

point

is

a

point

where

the

derivative

vanishes.

In

calculus

or

advanced

calculus,

the

main

interest

in

critical

point

and

critical

value

is

centered

on

the

search

for

extrema.

Although

they

are

important

in

their

applications,

they

are

of

equal

importance

in

answering

geometric

questions

such

as

the

immersions,

submanifolds,

and

hypersurfaces

as

the

following

theorem

illustrates.

Theorem

2 •

5.

1

Let

f:

MD

-+

N"

be

a

C"

map

and

b e

N"

be

a

regular

value.

Then

f"

1

(b)

is

a

submanifold

of

MD

whose

dimension

is

(m-n).

Next

we

use

a

special

but

remarkably

simple

notion

of

Lebesgue

measure

in

real

analysis.

This

particular

notion

of

measure

zero

gives

us

a

very

simple

yet

intuitive

definition

for

our

purpose

without

resorting

to

a

host

of

machinery.

Let

Wi

be

a

cube

in

R"

and

denote

its

volume

by

~(Wi).

A

set

S

~

R"

is

said

to

have

measure

zero,

~(S)

= o,

if

for

any

given

E >

0,

there

is

a

countable

family

of

Wi

such

that

(i)

s

~

uiwi;

(ii)

:r:

1

~CWi)

<

e.

It

should

be

noted

that

it

is

possible

for

the

continuous

(C")

image

of

a

set

of

measure

zero

to

have

positive

measure

(Royden

1963].

Nonetheless,

such

a

possibility

is

excluded

when

the

maps

are

C"

as

the

following

theeorem

shows.

Theorem

2.5.2

Let

S

~

U

~

R",

where

~(S)=

0

and

U

is

open,

and

let

f:

U-+

Rm

be

cr

(r

~

1).

Then

~(f(S))=

o.

Theorem

2.5.3

(Sard)

Let

f:

M

-+

N

be

C".

Then

the

set

of

critical

values

of

f

has

measure

zero

in

N.

Let

C

be

the

set

of

critical

points

of

f,

then

f(C)

is

the

set

of

critical

values

of

f,

and

the

complement

N -

f(C)

is

the

set

of

regular

values

of

f.

Since

M

can

be

covered

by

countable

neighborhoods

each

diffeomorphic

to

an

open

subset

of

Rm,

we

have

Corollary

2.5.4

(Brown)

The

set

of

regular

values

of

a

C"

map

f:

M

-+

N

is

everywhere

dense

in

N.

Corollary

2.5.5

Let

f:

MD-+

N"

(n

~

1)

be

onto

and

C".

Then

except

for

a

subset

of

N"

of

measure

zero,

for

all

y e

58

N",

f"

1

(y)

is

a

submanifold

of

M.

Moreover,

there

is

always

some y E

N"

such

that

f"

1

(y)

is

a

proper

submanifold

of

M.

Corollary

2.

5.

6

Let

the

n-disk

be

D"

= { x E

R"

I

II

x

II

S

1}

and

its

boundary

aD"

=

S""

1

'

an

(n-1)

-sphere.

Let

i:

S""

1

....

D"

be

the

inclusion

map.

Then

there

is

DQ

continuous

map

r:

D"

-+

S""

1

such

that

r-

i =

id

on

s"-

1

,

i.e.

,

no

continuous

r

such

that

for

each

x E

s"-

1

,

r(i

(x))

=

x.

If

such

an

r

exists,

it

is

called

a

retraction

of

D"

onto

s"-

1

•

For

n =

2,

this

corollary

can

be

worded

as

follows:

The

circle

is

not

a

retraction

of

the

closed

unit

disk

(normally

a

theorem

in

elementary

homotopic

theory).

As

a

corollary:

Any

continuous

map f

of

the

closed

disk

into

itself

has

a

fixed

point,

i.e.,

f(x

0

)

= X

0

for

some X

0

ED'.

This

is

the

n = 2

case

of

the

Brouwer

Fixed

Point

Theorem.

Corollary

2.5.7

(Brouwer

Fixed

Point

Theorem)

Let

D"

=

{x

E

R"l

llxll

S 1}

be

the

n-disk,

let

f:

D"

-+

D"

be

continuous.

Then

f

has

a

fixed

point,

i.e.,

there

is

some X

0

E

D"

such

that

f

(X

0

)

= X

0

•

It

has

been

realized

for

some

time

that

a

topological

space

can

often

be

characterized

by

the

properties

of

continuous

functions

on

it.

But

it

was

Morse

(1934)

who

first

called

attention

to

the

importance

of

nondegenerate

critical

points

and

invariant

index,

which

completely

characterizes

local

behavior

near

that

point.

Moreover,

the

number

of

critical

points

of

different

indices

relates

to

the

topology

of

the

manifold

by

means

of

the

Morse

inequalities.

In

addition,

a

sufficiently

isolated

critical

point

indicates

the

addition

of

a

cell

to

the

cell

decomposition

of

the

manifold.

Consequently,

this

shows

how

a

manifold

is

put

together,

as

a

cell

complex,

in

terms

of

the

critical

points

of

a

sufficiently

well

behaved

function.

On

the

other

hand,

Morse

theory

also

treats

geodesics

on

a

Riemannian

manifold.

Although

Morse

did

a

great

deal

more,

here

we

shall

only

touch

on

a few

items

directly

concerning

our

main

emphasis.

There

is

some

material

from

algebraic

topology,

such

as

homology,

Betti

numbers,

Euler

characteristics,

which

will

be

needed

when

we

get

to

the

59

Morse

inequalities.

At

the

appropriate

places,

we

shall

state

all

the

basic

facts

without

proof.

Let

us

recall

the

concept

of

a

critical

point.

Let

M

be

a

m-dimension

~

manifold

and

f:

M

~

R

be

a

~

function.

Then

a e M

is

a

critical

point

of

f

if

f

is

not

onto

at

a.

Since

the

range

of

df

is

a

!-dimension

vector

space

at

a,

a

is

a

critical

point

when

df

is

the

zero

map

at

a.

From a

more

conventional

viewpoint,

a e M

is

a

critical

point

if

there

is

a

coordinate

chart

rf>,.

:

u,.

~

Rm,

x e

u,.

such

that

all

first

partial

derivatives

of

f·

rf>,.-

1

vanish

at

rf>,.(a). And

a

real

number

b =

f(a),

where

a

is

a

critical

point,

is

called

a

critical

value.

Clearly,

the

first

partial

derivatives

at

a

critical

point

have

degenerate

behavior.

Nonetheless,

when

the

second

partial

derivatives

are

better

behaved,

it

is

called

a

nondegenerate

critical

point.

More

precisely,

if

a e M

is

a

critical

point

for

f:

M-+

R, f e

F(M),

and

a>

(f·rp,.-

1

)/ax;axi~

the

Hessian

at

a,

is

non-singular,

then

a

is

a

nondegenerate

critical

point

of

f.

It

can

be

shown

that

this

definition

is

independent

of

the

choice

of

the

coordinate

chart.

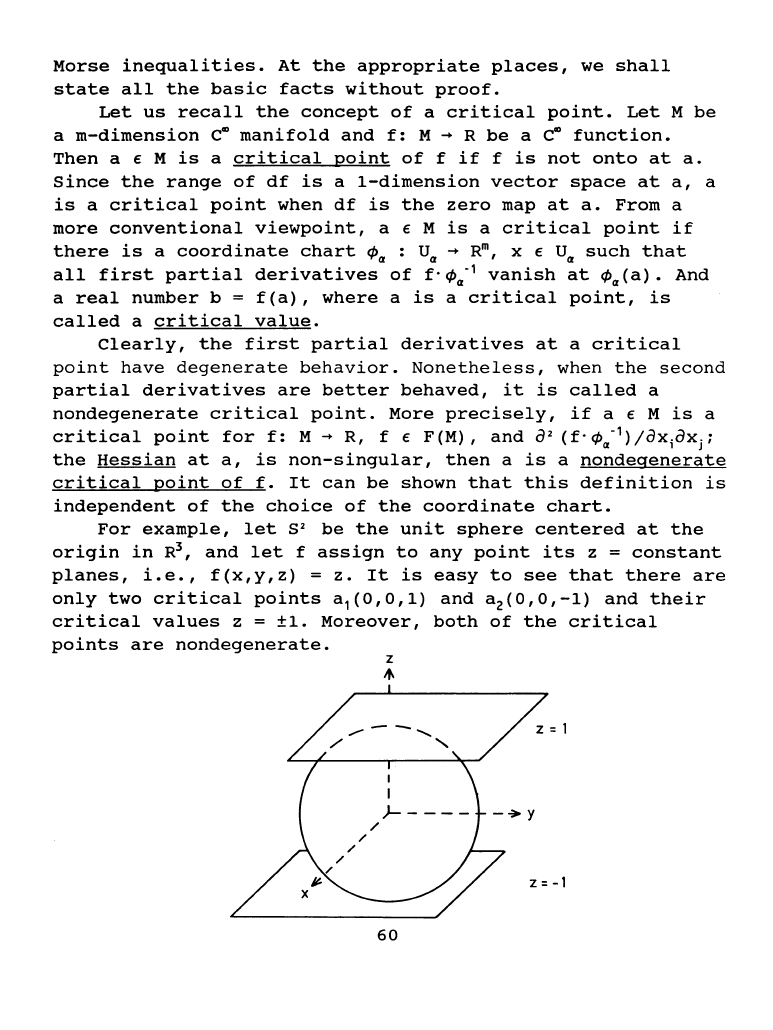

For

example,

let

S

2

be

the

unit

sphere

centered

at

the

origin

in

R

3

,

and

let

f

assign

to

any

point

its

z =

constant

planes,

i.e.,

f(x,y,z)

=

z.

It

is

easy

to

see

that

there

are

only

two

critical

points

a

1

(o,O,l)

and

a

2

(0,0,-1)

and

their

critical

values

z =

±1.

Moreover,

both

of

the

critical

points

are

nondegenerate.

z

.,.

60

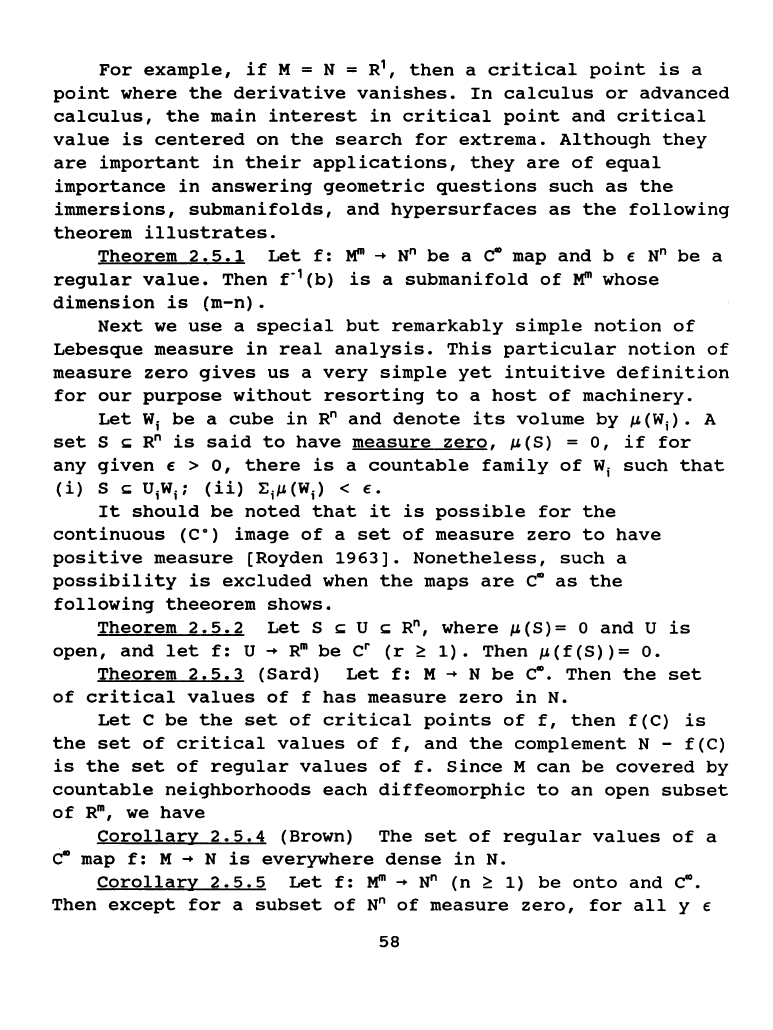

As

another

example,

let

T

2

be

a

2-dimension

torus

imbedded

as

a

submanifold

of

R

3

•

This

T

2

can

be

thought

of

as

the

surface

traced

by

the

circle

of

center

(2,0)

and

radius

1

in

the

(x,y)-

plane

as

this

plane

is

rotated

about

the

y-axis.

The

surface

has

the

equation

(X

2

+ y• + Z

2

+

3)

2

=

16(X

2

+ Z

2

).

It

is

easy

to

show

(and

easy

to

see

from

the

figure)

that

there

are

just

four

z =

constant

horizontal

planes

H

1

,

Hz,

H

3

,

and

H

4

that

are

tangent

planes

of

T

2

at

p

1

,

Pz• p

3

and

p

4

respectively,

coresponding

to

four

critical

points

for

the

function

z

on

T

2

and

H;

(i=1,2,3,4)

are

critical

levels.

Furthermore,

one

can

show

that

these

four

critical

points

P;

(i=1,2,3,4)

are

nondegenerate.

Notice

that,

in

this

example,

if

Nc

is

a

non-critical

level

of

z,

it

is

surrounded

by

neighboring

noncritical

levels,

all

of

which

are

homeomorphic

to

each

other.

For

example,

see

the

above

figure,

between

H

1

and

Hz

all

the

noncritical

levels

are

circles.

But

as

soon

as

we

cross

a

critical

level,

a

change

takes

place.

The

noncritical

levels

immediately

below

Hz

are

quite

different

from

those

immediately

above.

In

fact,

this

observation

is

valid

in

general.

61

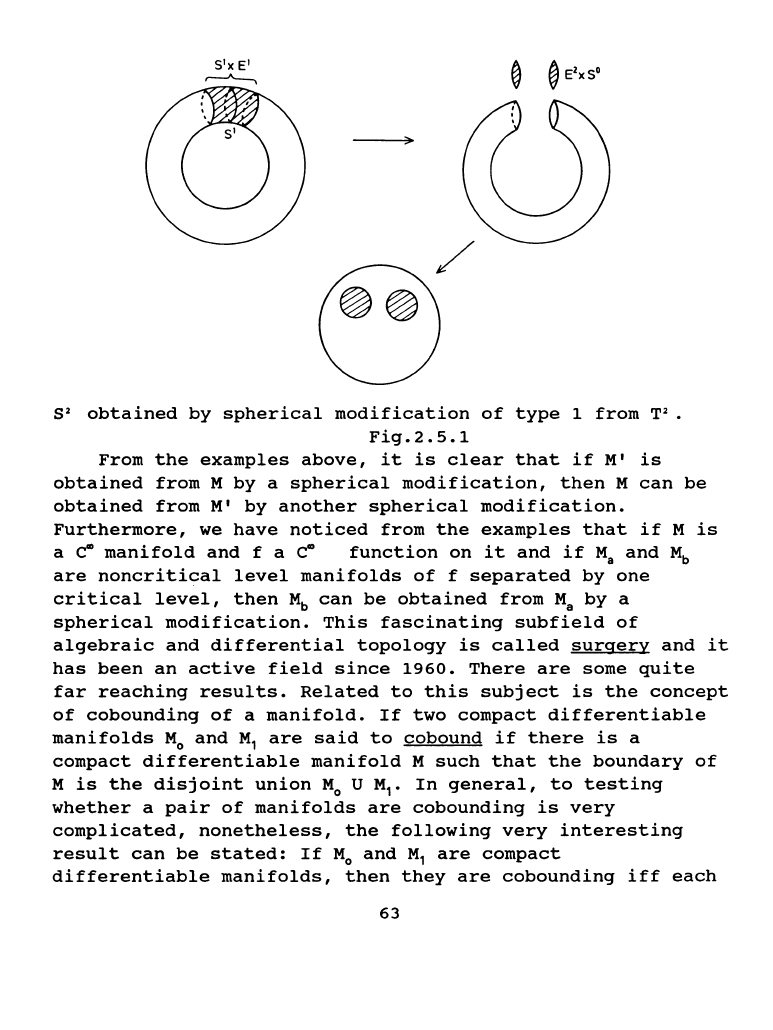

Let

the

differentiable

manifold

M

be

a

2-sphere

and

take

a

zero-dimension

sphere

s·

in

M.

s•

has

a

neighborhood

consisting

of

two

disjoint

disks.

This

is

of

the

form

s•xE

2

•

(E

2

is

a

2-

dim

disk).

Let

us

call

this

neighborhood

B.

Then

M

-Int

B

is

a

sphere

with

two

holes

in

it.

E

1

xs

1

is

a

cylinder

(here

E

1

is

a

line

segment),

and

when

its

ends

are

attached

to

the

circumferences

of

the

two

holes,

the

resulting

surface

is

a

sphere

with

one

handle,

i.e.,

a

torus.

Thus

the

torus

can

be

obtained

from

the

2-sphere

by

a

spherical

modification

of

type

o.

See

Fig.2.5.1.

Let

us

define

this

term

as

in

the

following:

Let

N

be

an

n-dim

~

manifold

and

sr

is

a

directly

embedded

submanifold

of

M.

sr

has

a

neighborhood

in

M

which

is

diffeomorphic

to

srxEn·r

and

we

call

it

B,

where

En·r

is

a

(n-r)

-cell.

The

boundary

of

B

is

the

manifold

srxsn·r-

1

•

Thus

M -

Int

B

is

a

manifold

with

boundary

and

the

boundary

is

srxsn·r·

1

•

But

srxsn·r-

1

is

also

a

boundary

of

the

~

manifold,

Er+

1

xsn·r·

1

•

So

the

two

manifolds

M

-Int

B

and

Er+

1

xsn·r·

1

can

be

joined

together

by

identifying

their

boundaries.

such

a

joined

space

is

a~

manifold

M'.

M'

is

said

to

be

obtained

from

M

by

a

spherical

modification

of

s

M-Int

8

T

2

obtained

by

spherical

modification

of

type

o

from

s•

•

62

s•

obtained

by

spherical

modification

of

type

1

from

T• •

Fig.2.5.1

From

the

examples

above,

it

is

clear

that

if

M'

is

obtained

from

M

by

a

spherical

modification,

then

M

can

be

obtained

from

M'

by

another

spherical

modification.

Furthermore,

we

have

noticed

from

the

examples

that

if

M

is

a

ca

manifold

and

f a

ca

function

on

it

and

if

M

8

and

Mb

are

noncritical

level

manifolds

of

f

separated

by

one

critical

level,

then

~

can

be

obtained

from

M

8

by

a

spherical

modification.

This

fascinating

subfield

of

algebraic

and

differential

topology

is

called

surgery

and

it

has

been

an

active

field

since

1960.

There

are

some

quite

far

reaching

results.

Related

to

this

subject

is

the

concept

of

cobounding

of

a

manifold.

If

two

compact

differentiable

manifolds

M

0

and

M

1

are

said

to

cobound

if

there

is

a

compact

differentiable

manifold

M

such

that

the

boundary

of

M

is

the

disjoint

union

M

0

U M

1

•

In

general,

to

testing

whether

a

pair

of

manifolds

are

cobounding

is

very

complicated,

nonetheless,

the

following

very

interesting

result

can

be

stated:

If

M

0

and

M

1

are

compact

differentiable

manifolds,

then

they

are

cobounding

iff

each

63