Krishnamurti Bhadriraju. The Dravidian Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

11.2

Earlier attempts

at subgrouping

the Dravidian

languages

491

[± human], but ann¯ı or all¯a is only [−human], e.g.

atanu

1

cepp-in-di

2

all¯a

3

c¯es-

æ

-

.

du

4

[he speak-past-noml all do-past-3m-sg]

‘he

1

did

4

all

3

that has been said

2

(by/to him)’

If Andronov chose all¯a, it would have been a case of retaining a cognate (ell¯a in Ta.

Ma. Ka.), but he chose ant¯a and noted it as a case of loss of a cognate. Again, for

item 31 ‘foot’, he cited Telugu p¯adamu, a learned borrowing from Sanskrit, although

a

.

dugu, a cognate with Ta. Ma. Ka. a

.

di, is the one widely used in Modern Telugu. By his

lexicostatistic study he worked out the time distance between pairs of languages. The

closest sisters, Tamil–Malay¯a

.

lam with a retention rate 73 per cent of cognates, are said

to have been separated by 1,043 years, i.e. the tenth century AD, which is, in any case,

the kno

wn historical date. The greatest

time depth is between Telugu

and Brahui, with

16 per cent retention of cognates indicating a distance of 6,075 years or 4100 BC. What is

surprising is that every language is separated from Brahui by over 5,000 years including

its closest sisters Ku

.

rux (by 5,505 years) and Malto (5,874)! Ku

.

rux and Malto are shown

to be closer to Tamil (4,596 and 4,872 years, respectively) than to Brahui (Andronov

1964c: 184). The fact of the matter is that Brahui has retained only 15 per cent of native

lexical items and the influence of Balochi has been immense, despite its contact with

Balochi being only for 1,000

years (Elfenbein 1987: 219,

229). We still do not have a

measure of how fast borrowed words replace native items. The misleading time depth is

caused by loss of many cognates in Brahui because of heavy borrowing from Balochi and

Indo-Aryan. However, in terms of shared phonological and morphological innovations,

it could not have been separated for more than a thousand years or so from Ku

.

rux–Malto.

Further, the Brahui specialist, Elfenbein, says, ‘...the estimate by “glottochronological”

methods that Brahui separated from the rest ca. 3000 BC, is perhaps not to be taken too

seriously’ (1987: 229). This is enough for Andronov’s glottochronology.

There are two other lexicostatistical studies by Kameswari (1969) and Namboodiri

(1976) that I reviewe

d in 1980 (see Krishnamurti 1985/2001a: 256

–7). There is wide

variation in the dates of separation of individual languages by the two authors, which

I pointed out as evidence for the unreliability of the technique employed; for instance,

‘Tamil and Telugu diverged around 400 BC to AD 400 (Kameswari), 11th century BC

(Namboodiri)’ (Krishnamurti 1985/2001a: 256).

11.2.2 Other proposals

Krishnamurti (1969b/2001a: 114–17, 1985/2001a: 255–7) has surveyed the earlier views

on subgrouping and the reasons for revisions at each stage. In TVB (ch. 4), he proposed

three branches: South Dravidian (treated as South Dravidian I in this volume), Central

492 Conc

lusion: a summary

and overview

Dravidian consisting of two subgroups, Telugu–Gondi–Ko

.

n

.

da–Kui–Kuvi–Pengo–

Man

.

da and Kolami–Naiki–Parji–Ollari–Gadaba; North Dravidian has the same mem-

bers, Ku

.

rux–Malto–Brahui. This proposal was widely accepted by the Dravidian schol-

ars and adopted for about three decades. In the mid 1970s, he found new evidence to

separate the Telugu–Man

.

da subgroup from Central Dravidian and designated it as an-

other branch of South Dravidian, called South Dravidian II or South-Central Dravidian,

changing the erstwhile South Dravidian to South Dravidian I (see Postscripts of chap-

ters 4 and 8 of Krishnamurti 2001a). This revision is widely accepted now, and it

is followed in this book for which exhaustive evidence is presented below in sec-

tion 11.3.

Southworth (1976) discusses in detail the subgrouping of the Dravidian languages

with three isogloss maps and makes some useful suggestions. Basing his assumption on

McAlpin’s hypothesis of Dravidian and Elamite being sisters of one parent language,

Proto-Elamo-Dravidian (which McAlpin has failed to establish), Southworth thinks

that ‘Dravidian speakers moved from somewhere near Mesopotamia to South Asia,

possibly sometime in the third millennium BC’ (1976: 131). Southworth sets up seven

subgroups for Dravidian besides the North Dravidian, namely (1) Kolami–Naiki–Parji–

Gadaba, (2) Kui–Kuvi–Ko

.

n

.

da–Pengo–Man

.

da, (3) Gondi–Telugu, (4) Tu

.

lu, (5) Kanna

.

da,

(6) Toda–Kota, (7) Tamil-Malay¯a

.

lam (1976: 131).

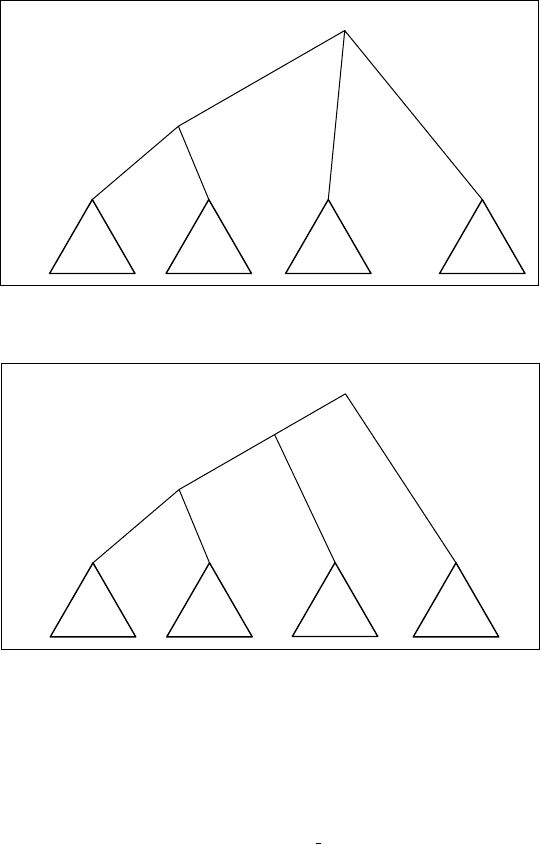

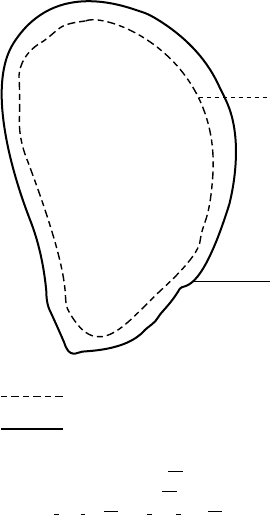

11.3 The subgrouping adopted in this book

The subgrouping

adopted in this book is that

Proto-Dravidian has three main branches.

The first branch is Proto-South Dravidian which split into South Dravidian I and South

Dravidian II (also called South Central Dravidian); the second is Central Dravidian

and the third North Dravidian (see section 1.4). This is the one which most Dravidian

scholars follow currently (figure 11.2a; also see Krishnamurti 2001a: 381, fig. 21.1).

It is also possible to set up an original binary division of Proto-Dravidian into Proto-

North Dravidian and Proto-South and Central Dravidian (see figure 11.2b). There is

lean evidence to set up a common stage of South and Central Dravidian, but generally

a binary division of a speech community is more likely than a ternary. A subsequent

split leads to the two branches

Proto-South Dravidian and Proto-Central Dravidian. The

former splits into South Dravidian

I and II.

In tables 11.1a–d, features from comparative phonology, morphology and syntax are

given a ‘+’ sign indicating innovation and a ‘−’ sign indicating retention within the

specified subgroup or a part of it. A ‘0’ sign says that the feature is either not registered

or not relevant in the specified subgroup. Discussion follows each table and isogloss

maps are presented at the end of the section.

Out of the nine features listed in table 11.1a, F1a, 2 and 3a support a common stage of

Proto-South Dravidian. Features 3c and 4 are exclusive innovations of South Dravidian II.

11.3

The subgrouping

adopted in this

book

493

Proto-Dravidian

Proto-

Central D

Proto-

North D

Proto-South D

Proto-South

D I

Proto-

South

D II

(a)

Figure 11.2a Proto-Dravidian with main branches (alternative 1)

Proto-Dravidian

Proto-South and

Central D

Proto-

Central

D

Proto-

North D

Proto-South D

Proto-South

D I

Proto-

South

D II

(b)

Figure 11.2b Proto-Dravidian with main branches (alternative 2)

Only F3b is an innovation restricted to Central Dravidian; F8b and 9 characterize North

Dravidian. F1b, 5 and 8a, on the one hand, and 6 on the other, demarcate smaller

subgroups within South Dravidian I and South Dravidian II, respectively. There are

other minor sound changes without a clear clue to subgrouping like

∗

w > b in Middle

Kanna

.

da which has spread

by diffusion to Ku

rumba, Ko

.

dagu, Tu

.

lu and Ba

.

daga; a similar

sound change has independently taken place in North Dravidian, presumably under the

influence of Eastern Indo-Aryan (section 4.5.4.1). This sound change is also shared by

Brahui and is one of the arguments to say that Brahui had not separated from Ku

.

rux

and Malto until around the eighth century CE. Another sound change which probably

involved diffusion as an important factor from Indo-Aryan is the deretroflexion of

∗

.

n

∗

.

l

to nlin several languages of South Dravidian II, Central Dravidian and North Dravidian

494 Conc

lusion: a summary

and overview

T

able 11.1a

Subgr

ouping supported

by phonolo

gical features

Reference/

Feature(s) = F SD I SD II CD ND remarks

1a. PD

∗

i

∗

u > PSD

∗

e

∗

o / +a

++−−section 4.4.2

1b. PSD

∗

e

∗

o >

∗

i

∗

u/ +a + Ta. Ma. − 0 0 section 4.4.2.2 (1)

2. PD

∗

c >

∗

s >

∗

h > Ø/# ++−−section 4.5.1.3.2

3a. PD

∗

t > r/V V, > d∼r/

∗

Vn

++ +section 4.5.5.3

3b. PD

∗

t > d/V V,

∗

n + section 4.5.5.3

(?retention)

3c. PSD

∗

t > PSD II

.

d/V V −+−−section 4.5.5.3

sporadic

4. Apical displacement −+−−sections 4.4.3,

4.5.7.3

5. (C)¯e-/¯o- > (C)¯a-0+ Kui–

Kuvi

0 0 section 4.4.2.2

6. Centralized vowels ¨e¨o + Ir. To.

Ku

r. Ko

.

d

0 0 0 section 4.4.4.2

7. PD

∗

n- > Ø- + Kol.

Nk.

section 4.5.3.2

Regular in CD;

sporadic in SD

8a. PD

∗

k > c/# V[−Back]C

[−Retroflex]

+ Ta. Ma. −−−section 4.5.1.4

8b. PD

∗

k > x/# V −−−+V = all except high

front vowels;

section 4.5.1.4

9. PD

∗

c > k/# V −−−+V = non-low vowels;

section 4.5.1.3

(sections 4.5.6–7) as it is in many Indo-Aryan languages of central and northern India.

Another sound change exclusively

innovated by Kanna

.

da and inherited by Ba

.

daga,

considered a dialect of Kanna

.

da that split off in about the sixteenth century CE, is

∗

p- > h- > Ø (section 4.5.1.1).

Among the nine morphological innovations in nominals listed in table 11.1b, there

are two that establish South Dravidian I and South Dravidian II as closer sisters, derived

from a common undivided stage, see F10 and 11. F12, 14 and 15 are clear innovations in

South Dravidian I, not shared by South Dravidian II; similarly, F13 is a shared innovation

in South Dravidian II. There are two features which are exclusive to Central Dravidian,

namely F16 and 17. There can be a question of how Telugu happens to have a numeral

derived from

∗

okk- beside the regular items o

.

n

.

du ‘one’ (n-msg), or-u

n

.

du ‘one man’,

¯or-ti ‘one woman’. The last two have become archaic, since Modern Telugu has only

11.3

The subgrouping

adopted in this

book

495

T

able 11.1b

Subgr

ouping supported

by morpholo

gical features

of nominals

Reference/

Feature(s) = F SD I SD II CD ND remarks

10.

∗

˜n¯an/˜nan- ‘I’ beside

∗

y¯an/yan- ‘I’

++−−section 6.4.1.1;

the root vowel:

archiphoneme

∗

˘

¯a/

˘

¯e

11. 2pl pronoun

∗

n¯ı-m >

∗

n¯ı-r ++−−section 6.4.1.2

12. Addition of

∗

-ka

.

l to the

1pl 2pl pronouns, e.g.

∗

y¯am-ka

.

l ‘we’

+ Ta. Ma.

Ko

.

d. Ku

r.

Ka. Kor. Tu.

−−−section 6.4.1.1

13. 1sg obl.

∗

n¯a-, 2sg obl

∗

n¯ı-;

1pl obl.

∗

m¯a-, 2pl obl

∗

m¯ı-

−+−−sections 6.4.1.1–2

14. Creation of

∗

aw-a

.

l etc.

3f sg

+−−−sections 6.2.2–3, 6.2.6

15. Loss of

∗

t in 3m sg

∗

aw-ant,

∗

iw-ant ‘he’

+−−−sections 6.2.2–3, 6.2.6

16. Numerals 1–4 +

derivational markers for

m sg, f sg, neu sg

−−+−sections 6.5, 6.5.1

17. okk- ‘one’ −−(+ Te.) +−section 6.5.1: ‘one’ (c)

18. Loss of –Vn as accusative

marker

Ta. Ma. Ir

Ko

.

d. Ku

r.

−−−section 6.3.2.1

o(k)ka- ‘one’ and its derivatives, ok(k)a-

.

du ‘one man’, ok(k)a-te ‘one woman’, ok

(ka)-

.

ti ‘one thing’. It is possible that the Central Dravidian innovation might have spread

to Telugu through diffusion at some prehistoric time, although, normally, the direction

of borrowing is from Telugu to the Central Dravidian languages. A more plausible

alternative is that the doublet was created in Pre-Telugu and spread to Central Dravidian

at an undivided stage of the latter. There is evidence of several prehistoric borrowings

from Telugu to Kolami–Naiki, e.g.

∗

n¯ır ‘you (pl)’ replaced Pre-Kolami

∗

¯ım, since the

oblique remains im-. This borrowing provides a valuable missing link in the prehistory of

Telugu, because inscriptions and literary records only show m¯ıru which replaced

∗

n¯ı-ru

(<<

∗

n¯ı-m) in Pre-Telugu (see Krishnamurti 2001a: 96–7). F18 is the absence of -Vn as

accusative mark

er in Tamil, Malay

¯a

.

lam, Iru

.

la, Ku

rumba and Ko

.

dagu which I consider

off-shoots from a stage of Pre-Tamil after Toda–Kota had split off in South Dravidian I.

This subgroup within South Dravidian I is supported by other isoglosses, e.g. see F6

above and discussion in section 4.4.4.2.

Out of the thirteen features identified under verbs in table 11.1c, F19, 21 and 31 support

the undivided stage of South Dravidian I and South Dravidian II; I have proposed that

496 Conc

lusion: a summary

and overview

T

able 11.1c

Subgr

ouping supported

by morpholo

gical features

of verbs

Reference/

Feature(s) = F SD I SD II CD ND remarks

19. Causative + past

∗

-(p)pi-ntt- >

∗

-(p)pi-nc-/

∗

-(p)pi-c-

+ Ta.

Ma. Ka

+− −sections 7.3.3–6

20. Tense–voice marking

NP ∼ NPP

+ Ta.

Ma. Ko

.

d.

To. Ko.

− 0 0 sections 5.4.4,

7.3.6–7

21. Paired intr/tr: NP vs. NPP ++−−section 7.3.6

22. Loss of past-tense

marker

∗

-kk

+++−section 7.4.1.6

23. Loss of past marker with

a dental

∗

-t or

∗

-tt

−−−+section 7.4.1.1

24. Generalization of

∗

-tt as

past marker

−+(+) Kol.

–Nk.

0 section 7.4.1.2

25. Non-past -um loss −−−+section 7.4.2.3

26. Perfective participle

∗

-cci 0 ++Pa.

Oll. Gad

0 sections 7.7.1.2

27. -Vt/

.

t as 2sg in finite verbs −−+Pa, Oll

Gad

− section 7.5.3

28. Past relative participle:

past + i

−+−−-a in SD I,

CD and ND;

section 7.7.2.1

29.

∗

cil > (

∗

sil > hil) >

∗

il

‘to be not’

++(Te.) −−section 7.10.6

30. Compound verb

contraction

−+(–Te.) −−Exception

Telugu; sections

7.13, 7.13.2

31. Use of

∗

taH-r ‘give to

1/2 pers’ as auxiliary

++0 0 section 7.14

Table 11.1d Subgrouping supported by morphosyntactic features of adjectives,

adverbs, clitics and syntax

Feature(s) = F SD I SD II CD ND Reference/remarks

32. Loss of several basic

adjectives

−− ++CD and ND lost 8 each;

section 8.2

33. Adverb

∗

˜n¯antu ‘today’ lost −− ++section 8.3

34. Loss of interrogative

particles -¯e,-¯o

−+ ++generalization of -¯a in SD II,

CD, ND; section 8.4.3

35. Use of t¯an ‘self ’ as an

emphatic particle;

alternatively -¯e

+− −−section 8.4.2

36. copular verb

∗

ir- ‘be’

substituting

∗

man-

+− −−The retention is

∗

man- ‘to be’;

section 7.15.1.ff.

11.3

The subgrouping

adopted in this

book

497

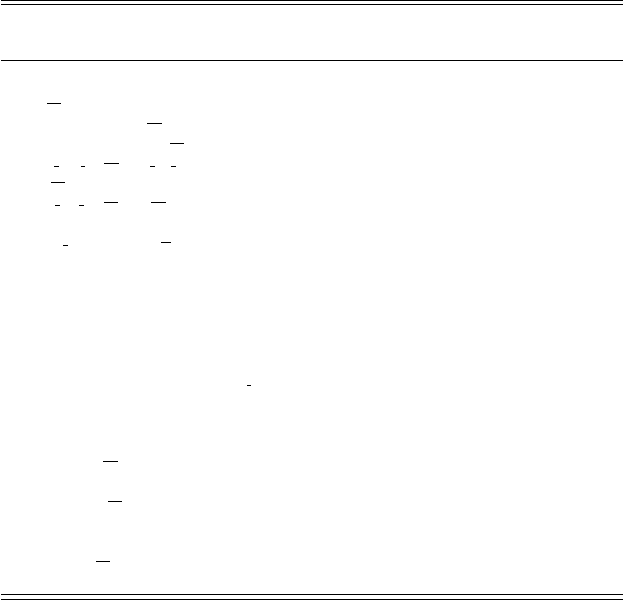

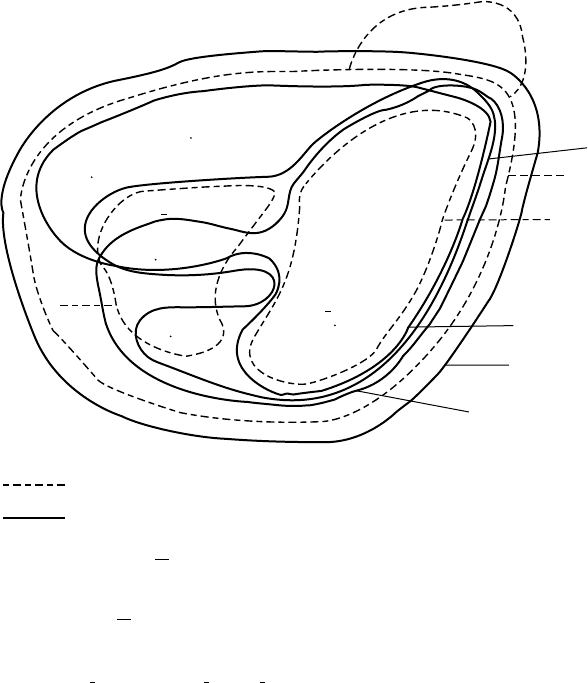

South

Dravidian II

South

Dravidian I

10, 11, 19, 21, 29, 31

1a, 2, 3a

Phonological isoglosses

Morphological isoglosses

F1a. PD

∗

i

∗

u > PSD

∗

eo/ +

∗

a

F2. PD

∗

c > s > h > Ø/#

F3a. PD t > r/V V, > d ∼ r/Vn

F10.

∗

˜n¯an/˜nan- ‘I’ beside

∗

y¯an/yan- ‘I’

F11. 2pl pronoun

∗

n¯ı-m >>

∗

n¯ı-r

F19. Causative + past

∗

-(p)pi-ntt- >

∗

-(p)pi-nc-/

∗

-(p)pi-c-

F21. Paired intr/tr: NP vs. NPP

F29.

∗

cil > (

∗

sil > hil) >

∗

il ‘to be not’ as auxiliary

F31. Use of

∗

taH-r ‘give to 1/2 pers’ as auxiliary

Figure 11.3 Shared innovations of South Dravidian I and II

F31 was a retention in South Dravidian; even then, it shows the togetherness of these

two subgroups since the feature is lost (not attested) in Central and North Dravidian.

In other words, retention supported by solid geographical contiguity could be taken

as a positive factor in subgrouping. Note F20 represents retention in a geographically

close-knit subgroup, which is established by other shared innovations. South Dravidian

I has

∗

il- ‘to be not’ derived from

∗

cil- (again a phonological feature), and Telugu, by

diffusion, shares this feature in l¯e-(<

∗

il-a-) ‘to be not’ with loss of c-. through the

intermediate stages of

∗

h- <

∗

s-. The generalization of

∗

-tt- as the past marker (F24)

distinguishes South Dravidian II, with the isogloss also spreading into some languages

of Central Dravidian. F30 is typically noticed in South Dravidian II, with the exception

of Telugu. It establishes Ko

.

n

.

da–Kui–Kuvi–Pengo–Man

.

da as a minor subgroup within

South Dravidian II.

498 Conc

lusion: a summary

and overview

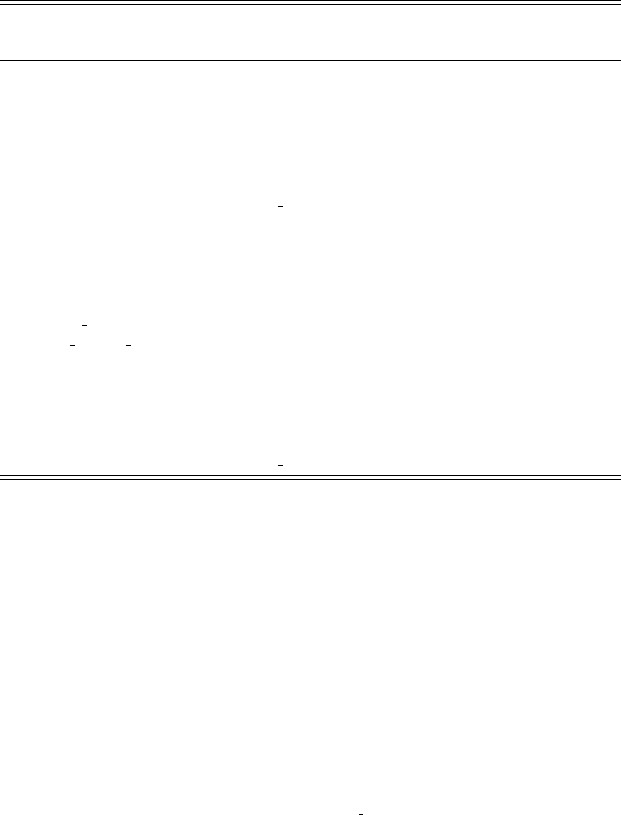

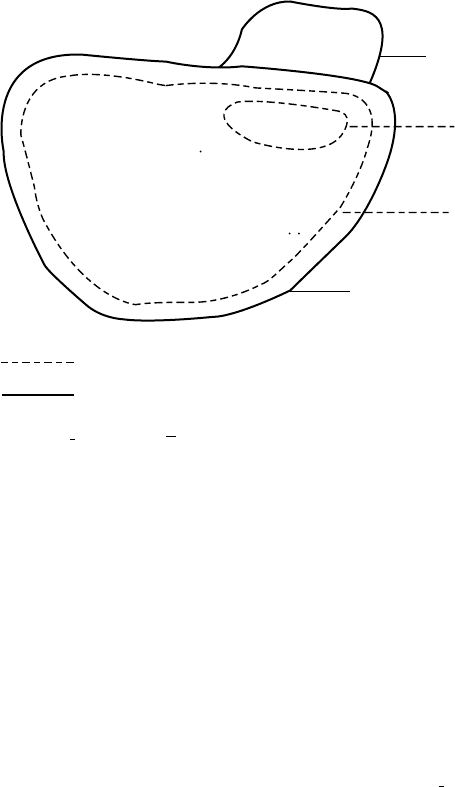

Telugu

Tamil

Kannada

Tulu

Koraga

Kurumba

Kodagu

Toda

Kota

Malayalam

20

6

14, 15, 35, 36

12

1b, 8a

2

18

Irula

Phonological isoglosses

Morphological isoglosses

F1b. PSD

∗

e

∗

o >

∗

i

∗

u/ +a

F2. PD

∗

c > Ø- (through

∗

s- >

∗

h- not attested directly)

F6. Centralized vowels in root syllables

F8a. PD

∗

k > c-/# V [–Back], C [–Retroflex]

F12. Addition of

∗

-ka

.

l (n-hpl suff) optionally to 1pl and 2pl

F14. Creation of

∗

aw-a

.

l etc. 3f sg

F15. Loss of

∗

t in 3m sg

∗

aw-ant,

∗

iw-ant ‘he’

F18. Loss of -Vn as accusative marker

F20. Tense–voice marking by final

NP ∼ NPP

F35. Use of t¯an ‘self ’ as an emphatic particle; alternatively -¯e

F36. copular verb

∗

ir- ‘be’ replacing

∗

man-

Figure 11.4 South Dravidian I (with the isogloss of F2 overlapping into Telugu)

There is no exclusive feature demarcating Central Dravidian but Kolami–Naiki and

Parji–Ollari–Gadaba emerge as minor subgroups in terms of F24 and 27.

The loss of a dental (F23) and the generalization of

∗

-kk (F22) as the past marker, and

the loss of non-past

∗

-um (F26), distinguish North Dravidian from others.

The five features listed

in table 11.1d give partial evidence for the established sub-

groups. The use of

∗

t¯an as an emphatic marker in addition to the normal

∗

¯e is an

11.3

The subgrouping

adopted in this

book

499

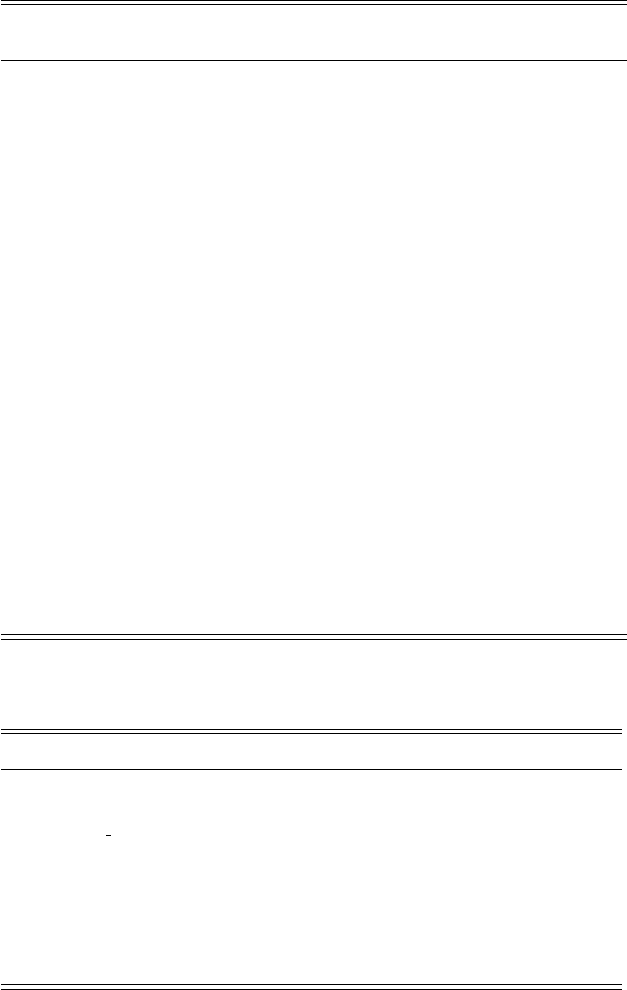

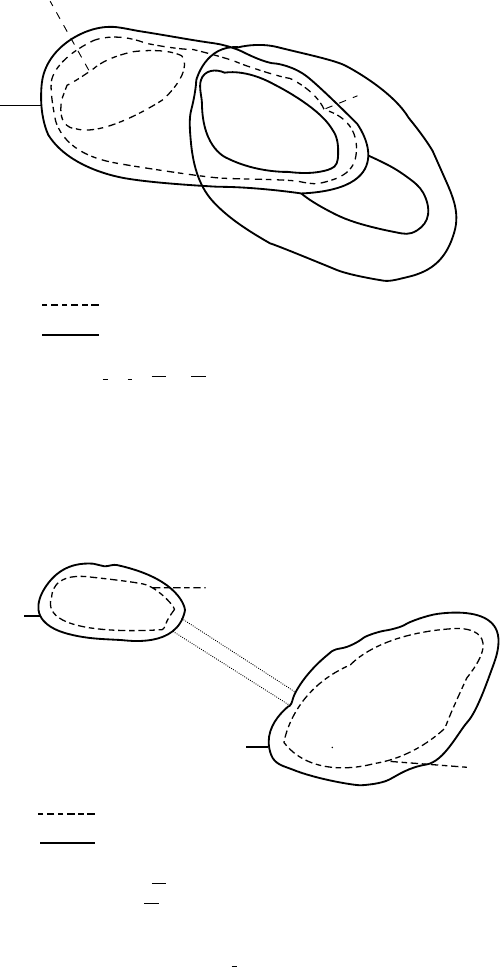

Parji–Ollari–

Gadaba

Gondi

Pengo

Manda

Kui-Kuvi

Konda

Telugu

13, 24, 26, 28, 30

3c, 4

5

26

Phonological isoglosses

Morphological isoglosses

F3c. PSD

∗

t > PSD II

.

d/V V

F4. Apical displacement

F5. (C)¯e-/¯o- > (C)¯a-

F13. 1sg obl

∗

n¯a-, 1pl obl

∗

m¯a-

2sg obl n¯ı-, 2pl obl

∗

m¯ı-

F24. Generalization of

∗

-tt as past marker

F26. Perfective participle

∗

-cci ∼

∗

-ci

F28. Past relative participle: past marker + i

F30. Compound verb contraction

Figure 11.5 South Dravidian II (with the isogloss of F26 overlapping into

Parji–Ollari–Gadaba of Central Dravidian)

innovation of South Dravidian I (F35). All but South Dravidian I show only -¯a as an

interrogative clitic for ‘yes–no’ responses (F34). The loss of several basic adjecti

ves

in Central

Dravidian and North Dravidian (but different lexical items) sho

ws that they

are independent branches (F32). Similarly, the Proto-Dravidian adverb

∗

˜n¯antu ‘today’ is

retained in South Dravidian I and South Dravidian II (F33), but lost in Central Dravidian

and North Dravidian. A very good feature is the replacement of

∗

man- ‘be’ by ir-in

South Dravidian I as a copular verb (F36).

Summary There are several exclusive isoglosses supporting Proto-South Dravidian

and the two branches from

it. There are also de

finite features setting of

f North Dravidian

from the rest. There are relatively fewer shared innovations by Central Dravidian, the

definite ones being F3b, 16, 17 and 32. The fact that Central Dravidian does not share

500 Conc

lusion: a summary

and overview

7

Naiki

Kolami

16, 17, 32

Parji

Ollari

Gadaba

27

17

SD II

Telugu

3b

26

Phonological isoglosses

Morphological isoglosses

F3b. PD

∗

t > d/V V, n (could be interpreted as a retention)

F7. PCD

∗

n- > Ø-

F16. Numerals 1–4 + derivational markers for msg, fsg, neusg

F17. okk- ‘one’

F26. Perfective participle -cci ∼ -ci

F27. -Vt/

.

t as 2sg in finite verbs

F32. Loss of several (8) basic adjectives

Figure 11.6 Central Dravidian

23, 25, 33, 34

23, 25, 33, 34

Brahui

8b, 9

Malto

Kurux

8b, 9

Phonological isoglosses

Morphological isoglosses

F8b. PD

∗

k > x/# V(V= all except high front vowels)

F9. PD

∗

c > k/# V(V= non-low vowels)

F23. Loss of past markers with a dental

∗

-t or

∗

-tt

F25. Loss of non-past –um

F33. Independent loss of

∗

˜n¯antu ‘today’

F34. Loss of interrogative clitics

∗

¯e,

∗

¯o

Figure 11.7 North Dravidian