Klir G.J. Uncertainity and Information. Foundations of Generalized Information Theory

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

m : C Æ [0, •]

that satisfies the following requirements:

(cm1) If ∆ŒC (family C is usually assumed to contain ∆), then m(∆) = 0;

(cm2) For every sequence A

1

, A

2

,...of pairwise disjoint sets of C,

Observe that probability is a classical measure such that C is a s-algebra and

m(X) = 1.

Property (cm2), which is the distinguishing feature of classical measures, is

called a countable additivity. A variant of this property, which is called a finite

additivity, is defined as follows:

(cm2¢) for every finite sequence A

1

, A

2

,...,A

n

, of pairwise disjoint sets of

C,

if thenAAA

i

i

n

i

i

n

i

i

n

==

=

Œ

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

=

()

Â

11

1

UU

C mm.

if thenAAA

i

i

i

i

i

i

=

•

=

•

=

•

Œ

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

=

()

Â

11

1

UU

C mm.

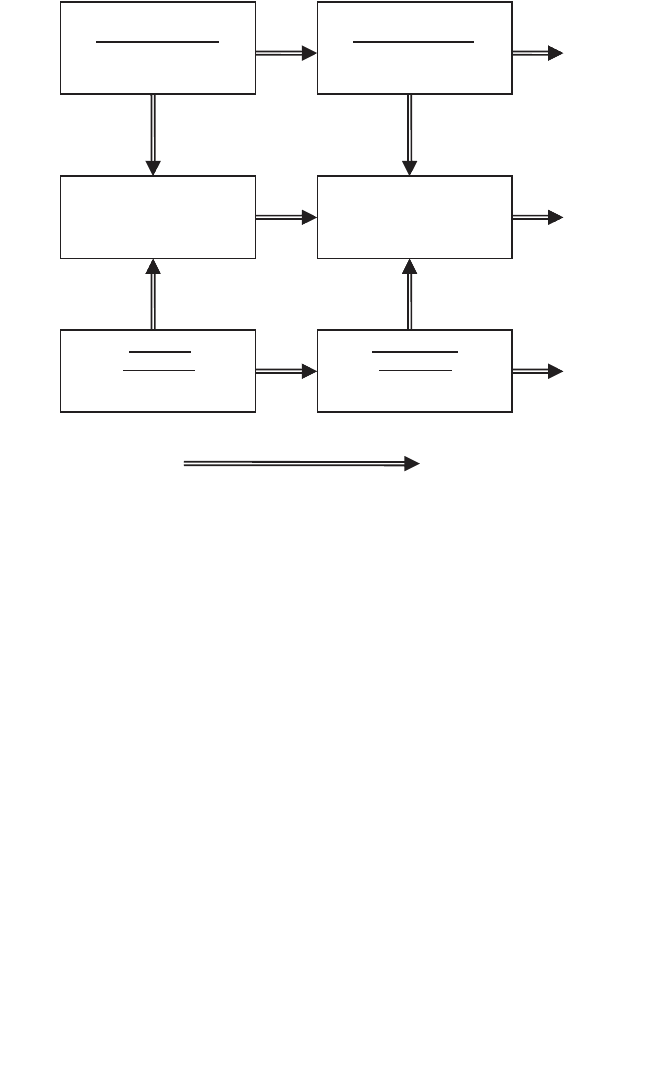

102 4. GENERALIZED MEASURES AND IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES

Boolean algebras:

Classical sets or

propositions

Weaker algebras:

Fuzzy sets or propositions

of special types

Classical

information

theory

Generalized

information

theory

Classical

Measures:

Additive set functions

Generalized

Measures:

Monotone set functions

with special properties

Generalizations

∑∑∑

∑∑∑

∑∑∑

Figure 4.1. Classical information theory and its generalizations.

It is well known that any countable additive measure is also finitely additive,

but not the other way around.

The requirement of additivity (countable or finite) of classical measures is

based on the assumption that disjoint sets are noninteractive with respect to

the measured property. This assumption is too restrictive in some application

contexts. Consider, for example, a set of workers in a workshop whose purpose

is to manufacture products of a specific type.Assume that the set is partitioned

into subsets (working groups) A

1

, A

2

,...,A

n

, and let m(A

i

) denote the number

of products made by group A

i

(i Œ⺞

n

) within a given unit of time.Then, clearly,

any of the following can happen for any two groups A

i

, A

j

:

•

m(A

i

» A

j

) = m(A

i

) + m(A

j

) when groups A

i

and A

j

work separately.

•

m(A

i

» A

j

) > m(A

i

) + m(A

j

) when the groups work together and their co-

operation is efficient.

•

m(A

i

» A

j

) < m(A

i

) + m(A

j

) when the groups work together and their co-

operation is inefficient.

Numerous other examples could be presented to illustrate that the addi-

tivity requirement of classical measures severely limits their applicability.

Some examples, relevant to the various issues of uncertainty formalization, are

discussed later in this chapter.

After recognizing that classical measures are too restrictive, it is not obvious

how to generalize them. One possibility is to eliminate the additivity re-

quirement and define generalized measures solely by the requirement (cm1).

Although this sweeping generalization seems too radical, it has been found

useful in some applications. However, its utility for dealing with uncertainty is

questionable. Another possibility is to replace the additivity requirement with

an appropriate weaker requirement. It is generally recognized that the highest

generalization of classical measures that is meaningful for formalizing uncer-

tainty functions is the one that replaces the additivity requirement with a

weaker requirement of monotonicity with respect to the subsethood ordering.

Generalized measures of this kind are called monotone measures. The follow-

ing is their formal definition.

Given universal set X and nonempty family C of subsets X (usually with an

appropriate algebraic structure), a monotone measure, m, on ·X, C Ò is a func-

tion of the type

that satisfies the following requirements:

(m1) m(∆) = 0 (vanishing at the empty set).

(m2) For all A, B ŒC, if A B, then m(A) £ m(B) (monotonicity).

(m3) For any increasing sequence A

1

A

2

...

of sets in C,

m :,C Æ•

[]

0

4.1. MONOTONE MEASURE 103

(m4) For any decreasing sequence A

1

A

2

...

of sets in C,

Observe that the same symbol, m, is used for both monotone and additive

measures. This does not create any notational confusion since additive mea-

sures are contained in the class of monotone measures. It is just required that

the meaning of the symbol be stated explicitly when it stands for some special

type of monotone measures, such as additive measures.

Functions that satisfy requirements (m1), (m2), and either (m3) or (m4) are

equally important in the theory of monotone measures. In fact, they are essen-

tial for formalizing imprecise probabilities (Section 4.3). These functions are

called semicontinuous from below or above, respectively. When the universal

set X is finite, requirements (m3) and (m4) are trivially satisfied and may thus

be disregarded. If X ŒC and m(X) = 1, m is called a regular monotone measure

(or regular semicontinuous monotone measure). Uncertainty functions of any

type are always regular monotone measures.

Observe that requirement (m2) defines measures that are actually monot-

one increasing. By changing the inequality m(A) £ m(B) in (m2) to m(A) ≥ m(B),

we can define measures that are monotone decreasing. Both types of monot-

one measures are useful, even though monotone increasing measures are more

common in dealing with uncertainty. Unless specified otherwise, the term

“monotone measure” is used in this book to refer to monotone increasing

measures that are regular.The utility of monotone decreasing measures is dis-

cussed later in the book.

The following inequalities hold for every monotone measure m: if A, B,

A » B ŒC, then

(4.1)

(4.2)

These inequalities follow from monotonicity of m and from the facts that

A « B A and A « B B, and similarly, A » B A and A » B B.If,in

addition, either the inequality

(4.3)

or the inequality

(4.4)

mmmAB A B»

()

£

()

+

()

mmmAB A B»

()

≥

()

+

()

mmmAB A B»

()

≥

() (){}

max , .

mmmAB A B«

()

£

() (){}

min , ,

if then lim A A A continuity from above

i

i

i

i

i=

•

Æ•

=

•

Œ

()

=

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

1

1

1

II

C,().mm

if then lim A A A continuity from below

i

i

i

ii

i=

•

Æ•

=

•

Œ

()

=

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

11

UU

C,().mm

104 4. GENERALIZED MEASURES AND IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES

holds for all A, B, A » B ŒC such that A « B =∆, the monotone measure is

called superadditive or subadditive, respectively.

It is easy to see that additivity implies monotonicity, but not the other way

around. For all A, B, A » B ŒC such that A « B =∆, a monotone measure m

is capable of capturing any of the following situations:

(a) m(A » B) > m(A) + m(B), which expresses a cooperative action or

synergy between A and B in terms of the measured property.

(b) m(A » B) = m(A) + m(B), which expresses the fact that A and B are

noninteractive with respect to the measured property.

(c) m(A » B) < m(A) + m(B), which expresses some sort of inhibitory effect

or incompatibility between A and B as far as the measured property is

concerned.

Observe that probability theory, which is based on classical measure theory,

is capable of capturing only situation (b). This demonstrates that the theory

of monotone measures provides us with a considerably broader framework

than probability theory for formalizing uncertainty.As a consequence,it allows

us to capture types of uncertainty that are beyond the scope of probability

theory.

The need for monotone measures arises in many problem areas. One

example is the area of ordinary measurement in physics.While additivity char-

acterizes well many types of measurement under idealized, error-free condi-

tions, it is not fully adequate to characterize most measurements under real,

physical conditions, when measurement errors are unavoidable. To illustrate

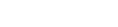

this claim by an example, consider two disjoint events, A and B, defined in

terms of adjoining intervals of real numbers, as shown in Figure 4.2a. Obser-

vations in close neighborhoods (within a measurement error) of the end points

4.1. MONOTONE MEASURE 105

Discount rate functions

Discount rate functions

1

0

Event A Event B

Event A B

(a)

(b)

( (

Figure 4.2. An example illustrating the violation of the additivity axiom of probability theory.

of each event are unreliable and should be properly discounted, for example,

according to the discount rate functions shown in Figure 4.2a. That is, obser-

vations in the neighborhoods of the end points should carry less evidence than

those outside them. The closer they are to the end points, the less evidence

they should carry. When measurements are taken for the union of the two

events, as shown in Figure 4.2b, one of the discount rate functions is not applic-

able. Hence, the same observations produce more evidence for the single event

A » B than for the two disjoint events A and B. This implies that the proba-

bility of A » B should be greater than the sum of the probabilities of A

and B. The additivity requirement is thus violated. To properly formalize

this situation, we need to use an appropriate monotone measure that is

superadditive.

For some historical reasons of little significance, monotone measures are

often referred to in literature as fuzzy measures. This name is somewhat con-

fusing,since no fuzzy sets are involved in the definition of monotone measures.

To avoid this confusion, the term “fuzzy measures” should be reserved to mea-

sures (additive or nonadditive) that are defined on families of fuzzy sets.

Since all monotone measures discussed in the rest of this book are regular,

it is reasonable to omit the adjective “regular.” Therefore, by convention, the

term “monotone measure” refers in the rest of this book to regular monotone

measures. Moreover, it is assumed, unless it is stated otherwise, that the uni-

versal set, X, is finite and that C = P(X). That is, it is normally assumed that

the monotone measures of concern are set functions

where X is a finite set, that satisfy the following requirements:

(m1¢) m(∆) = 0 and m(X ) = 1.

(m2¢) For all A, B ŒP(X), if A B, then m(A) £ m(B).

4.2. CHOQUET CAPACITIES

The general notion of a monotone measure provides us with a broad frame-

work, within which various special types of monotone measures can be

defined. Among these special types are the classical, additive measures, the

classical (crisp) possibility measures and necessity measures, and a great

variety of other nonadditive measures.

Each special type of monotone measures has a potential for formalizing a

certain type of uncertainty. In this section, an important family of special types

of nonadditive measures is introduced. Measures in this family are called

Choquet capacities. Other types of nonadditive measures, which have been uti-

lized for formalizing imprecise probabilities, are introduced in Chapter 5.

m :,,P X

()

Æ

[]

01

106 4. GENERALIZED MEASURES AND IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES

Given a particular integer k ≥ 2, a Choquet capacity of order k (or k-

monotone Choquet capacity) is a monotone measure m that satisfies the

inequalities

(4.5)

for all families of k subsets of X. For convenience, monotone measures that

are not required to satisfy Eq. (4.5) or any other special property are often

referred to as Choquet capacities of order 1 (1-monotone).That is, any general

monotone measure is also viewed as a Choquet capacity of order 1.

Since sets A

j

in Eq. (4.5) are not necessarily distinct, every Choquet capac-

ity of order k > 2 is also of order k¢=2,3,...,k. However, a capacity of order

k is clearly not a capacity of any higher order (k + 1, k + 2, etc.). Hence, capac-

ities of order 2, which satisfy the simple inequalities

(4.6)

for all pairs of subsets of X, are the most general capacities. The least general

ones are those of order k (or k-monotone) for all k ≥ 2. These are called

Choquet capacities of infinite order (or •-monotone). They satisfy the

inequalities

(4.7)

for every k ≥ 2 and every family of k subsets of X. Observe that probability

measures are special •-monotone Choquet capacities for which all the

inequalities in Eq. (4.7) collapse to equalities.

4.2.1. Möbius Representation

It is well known (see Note 4.4) that every set function

where X is a finite set, can be uniquely represented by another set function

via the formula

(4.8)

m

mmA B

AB

BB A

()

=-

() ()

-

Õ

Â

1

m

mX:,P

()

Æ ⺢

m :,P X

()

Æ ⺢

mmm

m

AA A A AA

AA A

ki

i

ij

ij

k

k

12

1

12

1

»»»

()

≥

()

-«

()

+

-+-

()

««

()

ÂÂ

<

+

...

... ...

mmmmAA A A AA

121212

»

()

≥

()

+

()

-«

()

mmAA

j

j

k

K

KN

K

j

jK

k

=

+

Õ

π∆

Œ

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

≥-

()

Ê

Ë

Á

ˆ

¯

˜

Â

1

1

1

UI

4.2. CHOQUET CAPACITIES 107

for all A ŒP(X). This formula is called a Möbius transform and function

m

m is

called a Möbius representation of m (or a Möbius function).

The Möbius transform is a one-to-one function and it is thus invertible. Its

inverse is defined for all A ŒP(X) by the formula

(4.9)

EXAMPLE 4.1. A set function m:P(X) Æ [0, 1], where X = {x

1

, x

2

, x

3

}, and its

Möbius representations

m

m are shown in Table 4.1. Subsets of A of X are

defined in the table by their characteristic functions. Given values m(A) for all

A ŒP(X), we can calculate the value of

m

m(A) for each A by the Möbius trans-

form Eq. (4.8). For example,

Function m can uniquely be reconstructed from its Möbius representation

m

m

by the inverse transform defined by Eq. (4.9). For example,

It can easily be shown that a set function m is a monotone measure (regular)

if and only if its Möbius representation

m

m has the following properties:

m

m

mmm

m

xx mxx mx mx

xx x mB

BX

23 23 2 3

123

0200305

1

,,

...,

,, .

{}()

=

{}()

+

{}()

+

{}()

=++=

{}()

=

()

=

Œ

()

Â

P

m

m

mmm

mmmm

m

mx x x x x x

mxxxxxxxxxxxx

x

23 23 2 3

123 123 12 13 23

05 0 03 02

,,

...,

,, ,, , , ,

{}()

=

{}()

-

{}()

-

{}()

=--=

{}()

=

{}()

-

{}()

-

{}()

-

{}()

+

1123

1040305000301

{}()

+

{}()

+

{}()

=- - - +++ =

mmxx

... ...

m

m

AmB

BB A

()

=

()

Õ

Â

.

108 4. GENERALIZED MEASURES AND IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES

Table 4.1. Set Function m and Its Möbius Representation

m

m

x

1

x

2

x

3

m(A)

m

m(A)

A: 0 0 0 0.0 0.0

1 0 0 0.0 0.0

0 1 0 0.0 0.0

0 0 1 0.3 0.3

1 1 0 0.4 0.4

1 0 1 0.3 0.0

0 1 1 0.5 0.2

1 1 1 1.0 0.1

Property (m1) follows directly from Eq. (4.8) and the requirement m(∆) = 0

of monotone measures. Property (m2) follows from Eq. (4.9) and the require-

ment m(X) of (regular) monotone measures. Property (m3) follows from

Eq. (4.8) and the fact that monotonicity of m holds if and only if it holds for

pairs A, A - {x} of sets (x ŒX). Observe that property (m3) implies that

m

m({x}) ≥ 0 for all x ŒX.

Additional properties of the Möbius representation have been recognized

for Choquet capacities of various orders k ≥ 2. Some of these properties, which

are utilized later in this book, are:

(m4) If m is a Choquet capacity of order k and 2 £|A|£k, then

m

m(A) ≥ 0.

(m5) m is a Choquet capacity of order • if and only if

m

m(A) ≥ 0 for all

A ŒP(X).

(m6) m is a probability measure if and only if

m

m(A) > 0 when |A|=1 and

m

m(A) = 0 otherwise.

(m7) m is a Choquet capacity of order k (k ≥ 2) if and only if

for all A ŒP(X) and all C ŒP(X) such that 2 £|C|£k.

For further information regarding the Möbius representation, including these

properties, see Note 4.4.

EXAMPLE 4.2. Four monotone measures defined on P({x

1

, x

2

, x

3

}) and their

Möbius representations are specified in Table 4.2. Measure m

1

is a monotone

measure, but it is not a Choquet capacity of any order k ≥ 2. This follows, for

example, from the inequalities

which violate the required inequalities (4.6) for Choquet capacities of order

2. It also follows from the negative values of m

1

({x

1

, x

2

}) and m

1

({x

2

, x

3

}), which

violates property (m4) for k = 2. Measure m

2

is not a Choquet capacity of any

order k ≥ 2 as well; for example,

mmm

mmm

11 2 11 1 2

12 3 12 13

xx x x

xxxx

{}

»

{}()

<

{}()

+

{}()

{}

»

{}()

<

{}()

+

{}()

,

,

mB

CBA

()

≥

ÕÕ

Â

0

mm

mmA

mmBAXxA

AX

xBA

10

21

3

()

∆

()

=

() ()

=

() ()

≥Œ

()

Œ

Œ

()

{}

ÕÕ

Â

Â

m

m

m

.

.

.

P

P0 for all and all

4.2. CHOQUET CAPACITIES 109

which violates the required inequalities (4.6) for 2-monotone measures.

However, this cannot be determined by property (m4). Measure m

3

is a

Choquet capacity of order 2, as can be easily verified by checking the required

inequalities (4.6). However, it is not a Choquet capacity of order 3, since

Observe, that this measure also violates property (m7) for k = 3. Measure m

4

is clearly a Choquet capacity of order • since m

4

(A) ≥ 0 for all A {x

1

, x

2

, x

3

}.

4.3. IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES: GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Classical probability theory requires that probabilities of all recognized alter-

natives (elementary events) be precise real numbers. Given these numbers,

probabilities of the various sets of alternatives are then uniquely determined

by the additivity property of probability measures. These, again, are precise

real numbers.This requirement of precision is overly restrictive since there are

many problem situations in which more than one probability distribution is

compatible with given evidence. One such situation is illustrated by the fol-

lowing example.

EXAMPLE 4.3. Consider a universal set X ¥ Y, where X = {x

1

, x

2

} and

Y = {y

1

, y

2

} are state sets of random variables X and Y, respectively. Assume

that we know the marginal probabilities p

X

(x

1

), p

X

(x

2

) = 1 - p

X

(x

1

),

p

Y

(y

1

), p

Y

(y

2

) = 1 - p

Y

(p

1

), and we want to use this information to determine

the unknown joint probabilities p

ij

= p(x

i

, y

j

)(i, j Π{1, 2}).According to the cal-

culus of probability theory, the joint probabilities are related to the marginal

probabilities by the following equations:

mmmm

mm m

312 13 23 312 313 3 23

31 3 2 33

xx xx x x xx xx x x

xx x

,,,,,,

.

{}

»

{}

»

{}()

<

{}()

+

{}()

+

{}()

-

{}()

-

{}()

-

{}()

mmmm

212 13 212 213 21

xx xx xx xx x,,,, ,

{}

»

{}()

<

{}()

+

{}()

-

{}()

110 4. GENERALIZED MEASURES AND IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES

Table 4.2 Examples of Monotone Measures Discussed in Example 4.2

x

1

x

2

x

3

m

1

(A) m

1

(A) m

2

(A) m

2

(A) m

3

(A) m

3

(A) m

4

(A) m

4

(A)

A: 0 0 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

1 0 0 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.3 0.3

0 1 0 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.0

0 0 1 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

110 0.5 -0.2 0.5 0.0 0.6 0.1 0.3 0.0

1 0 1 0.9 0.0 0.8 0.2 0.7 0.1 0.9 0.4

011 0.5 -0.1 0.5 0.2 0.5 0.2 0.3 0.1

1 1 1 1.0 0.2 1.0 -0.1 1.0 -0.1 1.0 0.0

(a) p

11

+ p

12

= p

X

(x

1

).

(b) p

21

+ p

22

= 1 - p

X

(x

1

).

(c) p

11

+ p

21

= p

Y

(y

1

).

(d) p

12

+ p

22

= 1 - p

Y

(y

1

).

Only three of these equations are linearly independent. For example, Eq. (d)

is a linear combination of the other equations: (d) = (a) + (b) - (c). By exclud-

ing it, the remaining three equations are linearly independent. Since they

contain four unknowns, one of them must be chosen as a free variable. Choos-

ing, for example, p

11

as the free variable, we obtain the following solution:

Since p

12

, p

21

, and p

22

are required to be nonnegative numbers, the free vari-

able p

11

is constrained by the inequalities

When a particular value of p

11

that satisfies these inequalities is chosen, the

values of p

12

, p

21

, and p

22

are uniquely determined. The resulting joint proba-

bility distribution is consistent with the given marginal distributions. Since

values of p

11

range over a closed interval of real numbers, there is a closed and

convex set of joint probability distributions that are consistent with the mar-

ginal distributions. According to the given evidence (the known marginal dis-

tributions), these are the only possible joint distributions, and the actual one

is among them. All the other joint distributions on X ¥ Y are not possible.

Consider, for example, that p

X

(x

1

) = 0.8 and p

Y

(y

1

) = 0.6 Then, the set of all

possible joint probability distribution functions is specified by the following

four statements:

Other types of incomplete information regarding a probability distribution

(e.g., knowing only the expected value of a random variable, analyzing statis-

tical data with observation gaps, etc.) result in sets of possible probability dis-

tributions as well. To deal with each given incomplete information correctly,

p

pp

pp

pp

11

12 11

21 11

22 11

04 06

08

06

04

Œ

[]

=-

=-

=-

., . ,

.,

.,

..

max , min , .01

11 11 11

px py p px py

XY XY

()

+

()

-

{}

££

() (){}

ppxp

ppyp

ppxpyp

X

Y

XY

12 1 11

21 1 11

22 1 1 11

1

=

()

-

=

()

-

=-

()

-

()

+

,

,

.

4.3. IMPRECISE PROBABILITIES: GENERAL PRINCIPLES 111