Kenny Anthony. Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

‘Necessary’ is not a term that applies to every being: but the disjunction

‘necessary or contingent’ does apply, right across the board (Ord. 3. 207).

Not only did Scotus lay a new emphasis on the necessary–contingent

disjunction, he introduced a fundamentally new notion of contingency.

It was generally believed by scholastics that many matters of fact were

contingent. It is contingent that I am sitting down, because it is possible for

me to stand up—a possibility that I can exemplify by standing up at the

very next moment. Scotus, like other scholastics, accept ed such a possibil-

ity: but he went further and claimed that at the very moment when I am

sitting down there exists a possibility of my standing up at that same

moment. This involves a new, more radical, form of contingency, which

has been aptly named ‘synchronic contingency’ (Lect. 17. 496–7).

Of course, Scotus is not claiming that at one and the same moment I can

be both sitting down and standing up. But he makes a distinction between

‘moments of time’ and ‘moments of nature’. At a single moment of time

there can be more than one moment of nature. At this moment of time

I am sitting down: but at this same moment of time there is another

moment of nature in which I am standing up. Moments of nature are

synchronic possibilities.

Scotus is not talking about mere logical possibility: an instant of nature is

a real possibility that is distinct from mere logical coherence. It is some-

thing that could be possible while the nature of the physical world remains

the same. Synchronic possibilities need not be compatible with each other,

as in the case just discussed; they are possible, a modern philosopher might

say, in diVerent possible worlds, not in the same possible world.

Scotus’ instants of nature are indeed the ancestor of the contemporary

philosophical concept of a possible world. His own account of the origin of

the world sees God as choosing to actualize one among an inWnite number

of possible universes. Later philosophers separated the notion of possible

worlds from the notion of creation, and began to take the word ‘world’ in a

more abstract way, so that any totality of compossible situations constitutes

a possible world. This abstract notion then came to be used as a means of

explicating every kind of power and possibility. Credit for the introduction

of the notion is often given to Leibniz, but, for better or worse, it belongs to

Scotus.

The introduction of the notion of synchronic contingency involves a

radical refashioning of the Aristotelian concepts of potentiality and actual-

METAPHYSICS

202

ity. For Scotus, unlike Aristotle or Aquinas, but like Avicenna, non-existent

items can possess a potentiality to exist: a potentiality that Scotus calls

objective potentiality, to contrast it with the Aristotelian potentiality, which

he calls subjective potentiality.

There are two ways in which something can be called a being in potentiality. In

one way it is the terminus of a power, that to which the power is directed—and

this is called being in potentiality objectively. Thus Antichrist is now said to be in

potentiality, and other things can be said to be in potentiality such as a whiteness

that is to be brought into existence. In the other way something is said to be in

potentiality as the subject of the power, or that in which the power inheres. In that

way something is said to be in potentiality subjectively, because it is in potentiality

to something but is not yet perfected by it (like a surface that is about to be

whitened). (Lect. 19. 80)

Non-existent items, Scotus explains, are individuated by their objective

potentiality: non-existent A diVers from non-existent B because if and

when they do exist A and B diVer from each other.

Other terms of the Aristotelian metaphysical arsenal are likewise re-

interpreted. The relationship between matter and form, for instance, is

expounded by Scotus in a novel way. For Aristotle, matter was a funda-

mental item in the analysis of substantial change. Substantial change is

the kind of change exempliWed when one element changes into another—

e.g. water into steam (air)—or a living being comes into or goes out of

existence—e.g. when a dog dies and its corpse decays. When a substance

of one kind changes into one or more substances of another kind, there

is, for Aristotle, a form that det ermines the nature of the substance

that precedes the change, and a diVerent form or forms determining the

nature of the substance(s) subsequent to the change. The element that

remains constant throughout the change is matter: matter, as such, is

not one kind of substance rather than another, and has, as such, no

properties. While form determines what kind of thing a substance is, it is

matter that determines which thing of that kind a substance is. Matter is the

principle of individuation, and form, we might say, is the principle of

speciWcation.

Scotus rejects both the notion of matter lacking properties and the

thesis that matter is the principle of individuation. Matter, according to

him, has properties such as quantity, and further, prior to such properties,

it has an essence of its own, even if it is virtually impossible for human

METAPHYSICS

203

beings to know what this essence is (Lect. 19. 101). Matter, indeed, can exist

without any form at all. Matter and form are really distinct, and it is well

within the power of God to create and conserve both immaterial form and

formless matter, each of them individuated in their own right.

Actual material substances are composed of both matter and form: here

Scotus agrees with Aristotle and Aquinas. Socrates, for instance, is a human

individual, composed of individual matter and an individual form of

humanity. Scotus gives a novel account, however, of the way in which

the individual substance and its matter and form are themselves individu-

ated. For Aquinas, the form of humanity is an individual form because it is

the human form of Socrates, and Socrates is individuated by his matter,

which in turn is individuated by being designated, or marked oV as a

particular parcel of matter (materia signata). For Scotus, on the other hand,

the form is an individual in its own right, independently of the matter of

Socrates and the substance Socrates (Ord. 7. 483).

What individuates Socrates is neither his matter nor his form but a third

thing, which is sometimes called his haecceitas, or thisness. In each thing,

Scotus tells us, there is an entitas individualis. ‘This entity is neither matter nor

form nor the composite thing, in so far as any of these is a nature; but it is

the ultimate reality of the being which is matter or form or a composite

thing’ (Ord. 7. 393).

According to Aristotelian orthodoxy, forms themselves neither come

into existence nor go out of existence: it is substances, not forms, that are

the subjects of generation and corruption. Strictly speaking we should say

not that the wisdom of Socrates comes into existence: that is only a

complicated way of saying that Socrates becomes wise. With regard to

the independently individuated substantial forms, in Scotus’ system, by

contrast, one can raise the question how they come into existence, and

whether they come out of nothing. Are they created, or do they evolve

from something pre-existing? Scotus rejects both these options. Forms do

not evolve from embryonic forms, or rationes seminales, as Augusti ne,

followed by Bonaventure, had thought. Postulating such entities does

not answer the question of the origin of forms, since the question would

simply rearise concerning whatever is the new element that distinguishes a

fully Xedged form from an e mbryonic one. On the other hand, we do not

want to say that forms are created; but we can avoid saying that if we

redeWne ‘creation’ not as bringing something into existence out of nothing,

METAPHYSICS

204

but as bringing something into existence in the absence of any precondition

(Lect. 19. 174).

Aquinas had maintained that in all material substances, including

human beings, there was only a single substantial form. Scotus denied

this: and in this denial he had, for once, the majority of medieval scholas-

tics on his side. He agreed with Aquinas that non-living entities had only a

single substantial form: a chemical compound did not retain the forms of

the elements of which they were composed. But living bodies—plants,

animals, and humans—possessed, in addition to the speciWc forms

belonging to their kinds, a common form of corporeality that made

them all bodies. He argued for this on the basis that a human body

immediately after death is the same body as it was immediately before

death, even though it is no longer an ensouled human being. Similar

considerations hold with regard to animals and plants.

Though Scotus held that the so ul is not the only substantial form of

humans, he did not, like some of his predecessors, believe that there were

three diVerent souls coexisting in each human being, an intellectual,

sensitive, and vegetative soul. If there were any forms in human beings

other than the soul and the form of corporeality, they were forms of

individual human organs—a possibility that Scotus once considered.7 But

in addition to the matter and the forms in a substance there is another item

which is neither matter nor form, the haecceity that makes it the individ-

ual it is. For the individuality of the matter and the individuality of the

form are between them not suYcient to individuate the composite sub-

stance (Lect. 17. 500).

How do all these items—matter, forms, haecceity—Wt together in the

concrete material substance? It is wrong to think of a material substance as

being an aggregate of which all these items are parts; for the parts could, on

Scotus’ account, all exist separately. Moreover, the whole substance has

properties that are diVerent from any of the properties of the parts listed:

for instance, the property of being a uniWed whole. In addition to those

parts, Scotus believed, we had to add an extra item: the relationship

between them—something which he is prepared to look on as yet another

part. But even after we have added this, we have to say that an individual

7 See R. Cross, The Physics of Duns Scotus: The ScientiWc Context of a Theological Vision (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1998), 68.

METAPHYSICS

205

material substance is an independent entity distinct from its matter, forms,

and relations (or any pair or triple of these items) (Oxon. 3. 2. 2 n. 8).

How are these diVerent entities—the whole and its several parts—

distinguished from each other? Scotus maintains that there is a real

distinction between the substance and its matter and form and the rela-

tionship between them. By saying that these items are really distinct he

means that it is at least logically possible for any of them to exist without

any of the others. He adds, for good measure, that if we say that the essence

or quiddity of a substance equals its matter plus its form, we must say that

the essence, no less than the substance itself, is really distinct from its

components.

What is the relation, we may ask, between the essence and the haecce-

ity—are these, too, really distinct from each other? In an individual such as

Socrates we have, according to Scotus, both a common human nature and

an individuating principle. The human nature is a real thing that is

common to both Socrates and Plato; if it were not real, Socrates would

not be any more like Plato than he is like a line scratched on a blackboard.

Equally, the individuating principle must be a real thing, otherwise Socra-

tes and Plato would be identical. The nature and the individuating

principle must be united to each other, and neither can exist in reality

apart from each other: we cannot encounter in the world a human nature

that is not anyone’s nature, nor can we meet an individual that is not an

individual of some kind or other. Yet we cannot identify the nature with

the haecceitas: if the nature of donkey were identical with the thisness of

the donkey Brownie, then every donkey would be Brownie.

To solve this enigma, Scotus introduces a new complication. Any

created essence, he says, has two features: replicability and individuality.

My essence as a human being is replicable: there can be, and are, other

human beings, essentially the same as myself. But it is also individual: it is

my essence, because it includes an individuating haecceity. The distinction

(Ord. 2. 345–6) between the essence and the haecceity is not a real distinc-

tion, but it is not a mere Wction or creation of the mind. It is, Scotus says, a

special kind of formal distinction, a distinctio formalis a parte rei, a formal

distinction ‘on the side of reality’. The essence and the haecceity are not

really distinct, in the way in which Socrates and Plato are distinct, or in the

way in which my two hands are distinct. Nor are they merely distinct in

thought, as Socrates and the teacher of Plato are. Prior to any thought

METAPHYSICS

206

about them, they are, he says, formally distinct: they are two distinct

formalities in the same thing. It is not clear to me, as it was not to many

of Scotus’ successors, how the introduction of this terminology clariWes the

problem it was meant to solve. One of the problems about understanding

exactly how Scotus meant his distinction to be understood is that the

illustrations he gives of its meaning, and the contexts in which he applies it,

are all themselves drawn from areas of great obscurity: the relationships

between the diVerent divine attributes, and the distinction between the

vegetative, sensitive, and rational souls in human beings.

Ockham’s Reductive Programme

William Ockham was one of the Wrst to reject Scotus’ formal distinction on

the side of reality. He arg ued.

Where there is a distinction or non-identity, there must be some contradictories

true of the items in question. But it is impossible that contradictories can be true of

any items unless they—or the items for which they supposit—are distinct things,

or distinct concepts, or distinct entia rationis , or a thing and a concept. But if the

distinction is from the nature of things, then they are not distinct concepts, nor a

pair of a thing plus a concept: therefore they are distinct things. (OTh. 2. 14)

But this assumes that the only candidates for being the terms of a distinc-

tion are (a) things, (b) entia rationis,(c) concepts. This begs the question

against Scotus, who accepted a much less restricted ontology. But the

move is characteristic of Ockham’s reductionist drive.

‘Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem’—‘Entities are not

to be multiplied beyond necessity.’ This is the famous ‘Ockham’s razor’,

designed to shave oV philosophers’ superXuous woolliness. The remark is

not, in fact, to be found in his survivin g writings.8 He did say similar things

such as ‘it is futile to do with many what can be done with few’ and

‘plurality is not to be assumed without necessity’, but he was not the Wrst

person to make such remarks. However, the slogan does sum up his

reductionist attitude towards the technical philosophical developments

of his predecessors.

8 It seems to have been attributed to him Wrst in a footnote to the Wadding edition of Scotus

in 1639.

METAPHYSICS

207

One of the Wrst superXuous entities to be subjected to the razor are

Scotus’ haecceities, or individuating principles. Scotus had argued that in

addition to the human nature of Socrates there must be something to

make it this nature; because if his human nature were itself this, then every

human nature would be this, that is to say would be the nature of Socrates.

Ockham believed neither in the common nature nor in the individuating

principle. All that exists in reality are individuals, and they just are

individual—they need no extra principle to individuate them. It is not

individuality, but universality, that needs explaining—indeed, explaining

away.

But Ockham’s nominalism is only part of his programme of metaphys-

ical deXation. In addition to universals, Ockham wanted to shave oV large

classes of individuals. For his medieval predecessors there were individuals

in every category—not only individual substances like Socrates and

Brownie the donkey, but individual accidents of many kinds, such as

Brownie’s whereabouts and Socrates’ relationship to Plato. Ockham re-

duced the ten Aristotelian categories to two. Only substances and qualities

were real.

Belief in individuals of ot her kinds, Ockham maintained, was due to a

naive assumption that to every word there corresponded an entity in the

world (OTh. 9. 565). This was what led people to invent ‘when-nesses’ and

‘wherenesses’—they might as well, he says, have invented also ‘andnesses’

and ‘butnesses’. Medieval philosophers did not, in fact, have a great deal

invested in some of the later categories of the Aristotelian catalogue. What

was serious in Ockham’s innovation was the denial of the reality of the

categories of quantity and of relation.

Ockham was not denying the distinction between the diVerent categor-

ies: what he was denying was that the distinction was more than a

conceptual one.

Substance, quality and quantity are distinct categories, even though they do not

signify an absolute reality distinct from substance and quality, because they are

distinct concepts and words signifying the same things but in a di Verent manner.

They are not synonymous names, because ‘substance’ signiWes all the things it

signiWes in one manner of signifying, namely directly; ‘quantity’ signiWes the same

things but in a diVerent manner of signifying, signifying substance directly and its

parts obliquely; for it signiWes a whole substance and connotes that it has parts

distant from other parts. (OTh. 9. 436)

METAPHYSICS

208

Ockham’s principal philosophical argument against the reality of quan-

tity is derived from the phenomena of expansion and contraction, rarefac-

tion and condensation. If a piece of metal is heated and expands from being

80 cm long to being 90 cm long, then, on the theory he is attacking, it

changes from possessing an accident of 80-cm-longhood to possessing

another accident of 90-cm-longhood. Ockham argues that it is diYcult

to give a convincing account of where the second accident has come from,

and what has become of the Wrst accident. Moreover, if the change is a

continuous one, so that the metal has expanded through lengths of 81 cm

to 82 cm and so on, then there will be an inWnite number of Xeeting

accidents coming into and going out of existence. This, Ockham claims,

strains our credulity. The local motion by which one part moves away

from another part is quite suYcient to explain such phenomena. Accord-

ingly, real accidents of quanti ty are quite superXuous, and should be

eliminated from philosophical consideration.

One might think that similar considerations might be used to show that

qualities, too, were not real accidents. Aristotle had listed four kinds of

quality: (a) dispositions like virtue and health, (b) inborn capacities, (c)

sensory properties like colour, taste, heat, (d) shapes. Ockham was willing

to eliminate some of the qualities in the Wrst class, like health and beauty,

and he applied his razor very explicitly to qualities in the fourth class.

When a proposition is true of reality, if one thing is suYcient to make it true, it is

superXuous to posit two. But propositions like ‘this substance is square’ ‘this

substance is round’ are true of reality; and a substance disposed in such and

such a way is quite suYcient for its truth. If the parts of a substance are laid out

along straight lines and are not moved locally and do not grow or shrink, then it is

contradictory that it should be Wrst square and then round. So squareness and

roundness add nothing to a substance and its parts. (OTh. 9. 707)

But he maintained that other qualities, notably colour, were diVerent.

It is impossible for something to pass from one contradictory to another without

gaining or losing something real, in cases where this is not accounted for by the

passage of time or by change of place. But a man is Wrst non-white, and afterwards

white, and this change is not accounted for by change of place or the passage of

time. Therefore, the whiteness is really distinct from the man. (OTh. 9. 706)

One might think, however, that a gradual change of colour was quite

parallel to a gradual change of size: the implausibility of an inWnite series of

METAPHYSICS

209

Xeeting accidents can be urged in this case too. What makes the diVerence

between the two cases, for Ockham, seems to be simply whether local

motion can be called in to explain the change to be explained.

Ockham’s arguments on the topic of relations are more powerful than

his arguments against real quantity. If a relation were a real entity distinct

from the terms of the relation, it would be capable of existing even if the

terms were not. Suppose Socrates is the father of Plato, and Plato is the son

of Socrates. Then there is a relation of paternity between Socrates and Plato.

It is absurd to say either that this relation could exist without Socrates ever

having begotten Plato, or that, Socrates having begotten Plato, God could

remove from Socrates the relation of paternity (OTh. 4. 368).

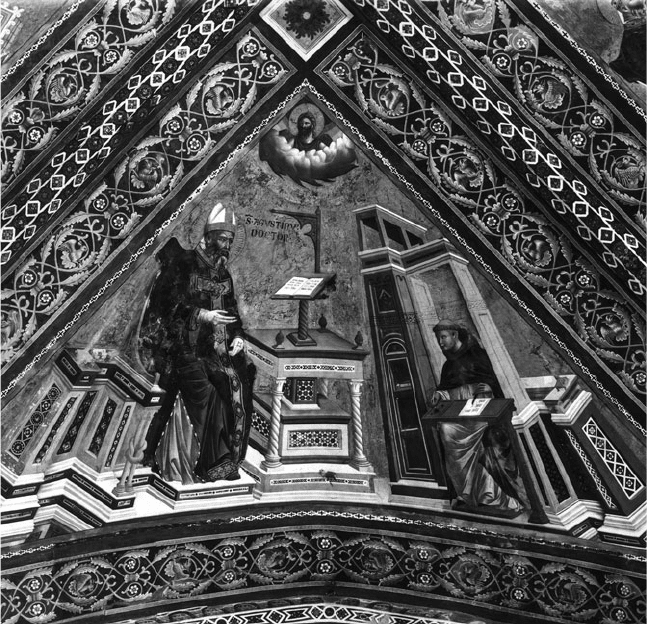

After the heyday of scholasticism, Augustine’s inXuence revived in the later middle

ages. Here in a fresco in the upper church in Assisi he is shown dictating to a

Dominican friar.

METAPHYSICS

210

The relation of likeness is an important one for Ockham, because of its

connection with real qualities: everything that has a certain real quality P is

like everything else that has that quality. A white wall is like every other

white wall. A painter who paints a wall white in Rome makes it like each of

the white walls in London. But if the relation of likeness was a real thing,

then the painter in Rome would be bringing into existence numerous

entities in London. Indeed if God made a thousand worlds and an agent

produced whiteness in one of them, he would produce likenesses in each

one of them (OTh. 1. 291, 9. 614). What is true of likeness is true of position.

If I move my Wnger, its position is changed in relation to everything else in

the world. If relations of position are real things, then by moving my Wnger

I create a gigantic number of converse relations throughout the universe.

Ockham is not saying that a relation is identical with its foundation. ‘I do

not say that a relation is really the same as its foundation ; but I say that a

relation is not the foundation but only an intention or concept in the soul,

signifying several absolute things’ (Ord. 1. 301). Relative terms signify the

absolute things that are the bearers of the relation, but they are connota-

tive terms that signify one term of the relation, connote the other, and

connote the way in which the two exist. Thus, when we say that A is next

to B, we are not talking about a real entity of ‘nextness’; we are signifying A,

connoting B, and saying that there is nothing getting in the way between

them (OTh. 4. 285, 312).

This, Ockham says, is what natural reason teaches: that there are no

such entities as relations. But, rather ignominiously, he is prepared to

accept the existence of such relations in certain cases because he believes

that certain Christian doct rines—the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Euchar-

ist—demand the existence of such relations. This naturally led to the

suspicion that he was a proponent of a double truth: that something

could be true in theology that was false in philosophy.

Wyclif and Determi nism

In the generation after Ockham, as we have seen, there was a reaction

against his nominalism and his general reductive programme. In Oxford

this took the form of a revival of Augustinianism, which in turn led to a

renewed interest in problems of predestination and determinism. John

METAPHYSICS

211