Kenny Anthony. Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the intellect would abstract without knowing from what it was abstracting’

(ibid.).

For Scotus, knowledge involves the presence in the mind of a represen-

tation of its object. Like Aquinas, he describes knowledge in terms of the

presence of a species or idea in the knowi ng subject. But whereas for

Aquinas the species was a concept, that is to say an ability of the intellect

in question, for Scotus it is the immediate object of knowledge. For

knowledge, he says, ‘the real presence of the object in itself is not required,

but something is required in which the object is represented. The species is

of such a nature that the object to be known is present in it not eVe ctively

or really, but by way of being displayed.’ (Ord. 3. 366).

For Aquinas the object of the intellect was itself really present, because it

was a universal, whose only existence was exactly such presence in the

mind. But Scotus, because he believes in intellectual knowledge of the

individual, conceives of intellectual knowledge on the model of sensory

awareness. When I see a white wall, the whiteness of the wall has an eVect

on my sight and my mind, but it cannot itself be present in my eye or my

mind; only some representation of it.

Scotus made a distinction between intuitive and abstractive cognition.

‘We should know that there can be two kinds of awareness and intellection

in the intellect: one intellection can be in the intellect inasmuch as it

abstracts from all existence; the other intellection can be of a thing in so far

as it is present in its existence’ (Lect. 2. 285). The distinction between

intuitive and abstractive cognition is not the same as that between sense

and intellect—the word ‘abstractive’ should not mislead us, even though

Scotus did believe that intellectual knowledge, in the present life, depends

on abstraction. There can be both intellectual and sensory intuitive know-

ledge; and the imagination, which is a sensory faculty, can have abstractive

knowledge (Quodl. 13, p. 27). Scotus makes a further distinction between

perfect and imperfect intuitive knowledge: perfect intuitive knowledge is of

an existing object as present, imperfect intuitive knowledge is of an existing

object as future or past.

Abstractive knowledge is knowledge of the essence of an object which

leaves in suspense the questi on whether the object exists or not (Quodl.7,p.

8). Remember that, for Scotus, essences include individual essences; so that

abstractive knowledge is not just knowledge of abstract truths. The notion

is a diYcult one: there cannot, surely, be knowledge that p if p is not

KNOWLEDGE

172

the case. Perhaps we can get round this by insisting that ‘knowledge’ is not

the right translation of ‘cognitio’. We are, however, left with a state of

mind, the cognitio that p, which (a) shares the psychological status of the

knowledge that p and (b) is compatible with p’s not being the case.

Moreover, the question arises how we can tell whether, in any particular

case, our state of mind is one of intuitive or abstractive cognition. Are the

two distinguishable by some infallible inner mark? If so, what is it? If not,

how can we ever be sure we really know something?

Intuitive and Abstractive Knowledge in Ockham

These problems with the notion of abstractive knowledge open a road to

scepticism, which trou bled Scotus himself (Lect. 2. 285). Because the distinc-

tion between two kinds of knowledge was extremely inXuential in the years

succeeding Scotus’ death, the road which it opened was travelled, to ever

greater lengths, by his successors. We may begin with William Ockham.

In introducing the notions of intuitive and abstractive knowledge Ock-

ham makes a distinction between apprehension and judgement. We appre-

hend single terms and propositions of all kinds; but we assent only to

complex thoughts. We can think a complex thought without assenting to

it, that is to say without judging that it is true. On the other hand, we

cannot make a judgement without apprehending the content of the

judgement. Knowledge involves both apprehension and judgement; and

both apprehension and judgement involve knowledge of the simple terms

entering into the complex thought in question (OTh. 1. 16–21).

Knowledge of a non-complex may be abstractive or intuitive. If it is

abstractive, it abstracts from whether or not the thing exists and whatever

contingent properties it may have. Intuitive knowledge is deWned as follows

by Ockham: ‘Intuitive knowledge is knowledge of such a kind as to enable

one to know whether a thing exists or not, so that if the thing does exist,

the intelle ct immediately judges that it exists, and has evident awareness of

its existence, unless perchance it is impeded because of some imperfection

in that knowledge’ (OTh. 1. 31). Intuitive existence can concern not only

the existence but the properties of things. If Socrates is white, my intuitive

knowledge of Socrates and of whiteness can give me evident awareness that

Socrates is white. Intuitive knowledge is fundamental for any knowledge of

KNOWLEDGE

173

contingent truths; no contingent truth can be known by abstractive

knowledge (OTh. 1. 32).

On Wrst reading, one is inclined to think that by ‘intuitive knowledge’

Ockham means sensory awareness. It is then natural to take his thesis that

contingent truths can be known only by intuitive knowledge to be a

forthright statement of empiricism, the doctrine that all knowledge of

facts is derived from the senses. But Ockham insists that there is a purely

intellectual form of intuitive knowledge. Mere sensation, he says, is incap-

able of causing a judgement in the intellect (OTh. 1. 22). Moreover, there

are many contingent truths about our own minds—our thoughts, aVec-

tions, pleasures, and pains—that are not perceptible by the senses. None-

theless, we know these truths: it must be by an intellectual intuitive

knowledge (OTh. 1. 28).

In the natural order of things, intuitive knowledge of objects is caused by

the objects themselves. When I look at the sky and see the stars, the stars

cause in me both a sensory and an intellectual awareness of their existence.

But a star and my awareness of it are two diVerent things, and God could

destroy one of them without destroying the other. Whatever God does

through secondary causes, he can do directly by his own power. So the

awareness normally caused by the stars could be caused by him in the

absence of the stars.

However, Ockham says, such knowledge would not be evident know-

ledge. ‘God cannot cause in us knowledge of such a kind as to make it

appear evidently to us that a thing is present when in fact it is absent,

because that involves a contradiction. Evident knowledge implies that

matters are in reality as stated by the proposition to which assent is

given’ (OTh. 9. 499). Whereas, for most writers, only what is true can be

known, for Ockham, it seems, one can know truly or falsely; but only what

is true can be evidently known. If God makes me judge that something is

present when it is absent, Ockham says, then my knowledge is not

intuitive, but abstractive. But that seems to imply that I cannot even tell

(short of a divine revelation) which bits of my knowledge are intuitive and

which are abstractive.6

6 The relation in Ockham between intuitive knowledge, assent, and truth is a matter of

much current controversy. For two contrasting opinions, see Eleonore Stump, ‘The Mechan-

isms of Cognition’, and E. Karger, ‘Ockham’s Misunderstood Theory of Intuitive and Abstractive

Cognition’, in CCO.

KNOWLEDGE

174

If intuitive knowledge is our only route to empirical truth, and intuitive

knowledge is compatible with falsehood, how can we ever be sure of

empirical truths? To be sure, my deception about the existence of the

star could only come about by a miracle; and Ockham adds that God could

work a further miracle, suspending the normal link between intuitive

knowledge and assent, so that I could refrain from the false judgement

that there is a star in sight (OTh. 9. 499). But that seems little comfor t for

the revelation that I never have any way of telling whether a piece of

intuitive knowledge is evident or not, or even whether a piece of know-

ledge is intuitive or abstractive.

It is to be remarked that Ockham’s position is quite diVerent from that

of some later empiricists who have sought to preserve the link between

knowledge and truth by saying that the immediate object of intuitive

awareness is not any external object, but something private, such as a

sense-datum. Ockham says explicitly that if the sensory vision of a colour

were preserved by God in the absence of the colour, the immediate object

both of the sensory and of the intellectual vision would be the colour itself,

non-existent though it was (OTh . 1. 39).

KNOWLEDGE

175

5

Physics

Augustine on Time

I

n the eleventh book of the Confessions there is a celebrated inquiry into the

nature of time. The peg on which the discussion hangs is the question of

an objector: what was God doing before the world began? Augustine toys

with, but rejects, the answer ‘Preparing hell for people who look too

curiously into deep matters’ (Conf. XI. 12. 14). The diY culty is serious: if

Wrst God was idle and then creative, surely that involves a change in the

unchangeable one? The answer Augustine develops is that before heaven

and earth were created there was no such thing as time, and wit hout time

there can be no change. It is folly to say that innumerable ages passed

before God created anything; because God is the creator of ages, so there

were no ages before creation. ‘You made time itself, so no time could pass

before you made time. But if before heaven and earth there was no such

thing as time, why do people ask what you were doing then? When there

was no time, there was no ‘‘then’’ ’ (Conf. XI. 13. 15). Equally, we cannot ask

why the world was not created sooner, for before the world there was no

sooner. It is misleading to say even of God that he existed at a time earlier

than the world’s creation, for there is no succession in God. In him today

does not replace yesterday, nor give way to tomorrow; there is only a single

eternal present.

In treating time as a creature, it may seem as if Augustine is treating time

as a solid entity comparable to the items that make up the universe. But as

his argument develops, it turns out that he regards time as fundamentally

unreal. ‘What is time?’ he asks. ‘If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to

explain to an inquirer, I know not.’ Time is made up of past, present, and

future. But the past is no longer, and the future has not yet come. So the

only real time is the present: but a present that is nothing but present is not

time, but eternity (Conf. XI. 14. 17).

We speak of longer and shorter times: ten days ago is a short time back,

and a hundred years is a long time ahead. But neither past nor future are in

existence, so how can they be long or short? How can we measure time?

Suppose we say of a past period that it was long: do we mean that it was

long when it was past, or long when it was present? Only the latter makes

sense, but how can anything be long in the present, since the present is

instantaneous? A hundred year s is a long time: but how can a hundred

years be present? During any year of the century, some years will be in the

past and some in the future. Perhaps we are in the last year of the century:

but even that year is not present, since some months of it are past and some

future. The same argument can be used about days and hours: an hour

itself is made up of fugitive moments. The only thing that can really be

called ‘present’ is an indivisible atom of time, Xying instantly from future

into past. But something that is not divisible into past and future has no

duration (Conf. XI. 15. 20).

No collection of instants can add up to more than an instant. The stages

of any period of time never coexist; how then can they be added up to form

a whole? Any measurement we make must be made in the present: but

how can we measure what has already gone by or has not yet arrived?

Augustine’s solution to the perplexities he has raised is to say that time is

really only in the mind. His past boyhood exists now, in his memory.

Tomorrow’s sunrise exists now, in his prediction. The past is not, but we

behold it in the present when it is, at the moment, in memory. The future

is not; all that there is is our present foreseeing. Instead of saying that there

are three times, past, present, and future, we should say that there is a

present of things past (which is memory), a present of things present

(which is sight), and a present of things future (which is antici pation).

A length of time is not really a length of time, but a length of memory, or a

length of anticipation. Present consciousness is what I measure when

I measure periods of time (Conf . XI. 27. 36).

This is surely not a satisfactory response to the paradoxes Augustine so

eloquently constructed. Consider my present memory of a childhood

event. Does my remembering occupy only an instant? In which case it

lasts no time and cannot be measured. Does it take time? In which case,

PHYSICS

177

some of it must be past and some of it future—and in either case,

therefore, unmeasurable. If we waive these points, we can still ask how a

current memory can be used to measure a past event. Surely we can have a

brief memory of a long, boring event in the past, and on the other hand we

can dwell long in memory on some momentary but traumatic past event.

Augustine’s own text reveals that he was not happy with his solution.

Our memories and anticipations are signs of past and future events; but, he

says, that which we remember and anticipate is something diVerent from

these signs and is not present (Conf. XI. 23. 24). The way to deal with his

paradoxes is not to put forward a subjective theory of time, but rather to

untangle the knots which went into their knitting. Our concept of time

makes use of two diVerent temporal series: one that is constructed by

means of the concepts of earlier and later, and another that is constructed

by means of the concepts of past and future. Augustine’s paradoxes arise

through weaving together threads from the two systems, and can only be

dissolved by untangling the thread s. It took philosophers many centuries

to do so, and some indeed believe that the task has not yet been satisfactor-

ily completed.1

Augustine’s interest in time was directed by his concern to elucidate the

Christian doctrine of creation. ‘Some people’, he wrote, ‘agree that the

world is created by God, but refuse to admit that it began in time, allowing

it a beginning only in the sense that it is being perpetually created’ (DCD

IX. 4 ). He has some sympathy with these people: they want to avoid

attributing to God any sudden impetuous action, and it is certainly

conceivable that something could lack a beginning and yet be causally

dependent. He quotes them as saying ‘If a foot had been planted from all

eternity in dust, the footprint would always be beneath it; but no one

would doubt that it was the footprint that was caused by the foot, though

there was no temporal priority of one over the other’ (DCD X. 31).

Those who say that the world has existed for ever are almost right, on

Augustine’s view. If all they mean is that there was no time when there was

no created world, they are correct, for time and creation began together. It

is as wrong to think that there was time before the world began as it is to

think that there is space beyond where the world ends. So we cannot say

1 See A. N. Prior, ‘Changes in Events and Changes in Things’, in his Papers on Time and Tense

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968).

PHYSICS

178

that God made the world after so and so many ages had passed. This does

not mean that we cannot set a date for creation, but we have to do so by

counting backwards from the present, not, impossibly, counting forward

from the Wrst moment of eternity. Scripture tells us, in fact, that the world

was created less than six thousand years ago (DCD IX. 4, 12. 11).

Philoponus, Critic of Aristotle

There was a well-known series of arguments, deriving from Aristotle, to the

eVect that the universe cannot have had a beginning. Augustine was aware

of some of these arguments, and attempts to counter them, but a deWnitive

attack on Aristotle’s reasoning was Wrst made by John Philoponus.

Philoponus’ work Against Aristotle, On the Eternity of the World survives only

in quotations gleaned from the commentaries of his adversary Simplicius,

but the fragments are substantial enough to enable his argumentation to

be reconstructed with conWdence.2 The Wrst part of the work is an attack

on Aristotle’s theory of the quintessence, namely the belief that in addition

to the four elements of earth, air, Wre, and water wit h their natural

motions upward and downward, there is a Wfth element, ether, whose

natural motion is circular. The heavenly and sublunar regions of the

universe, he argues, are essentially of the same nature, composed of the

same elements (books 1–3).

Aristotle had argued that the heavens must be eternal because all things

that come into being do so out of a contrary, and the quintessence has no

contrary because there is no contrary to a circular motion (De Caelo 1. 3.

270a 12–22). Philoponus pointed out that the complexity of planetary

motions could not be explained simply by appealing to a tendency of

celestial substance to travel in a circle. More importantly, he denied that

everything comes into being from a contrary. Creation is bringing some-

thing into being out of nothing; but that does not mean that non-being is

the material out of which creatures are constructed, in the way that timber

is the material out of which ships are constructed. It simply means that

there is no thing out of which it is created. The eternity of the world,

2 The reconstruction has been carried out by Christian Wildberg, who has translated the

reconstructed text as Philoponus: Against Aristotle on the Eternity of the World (London: Duckworth,

1987).

PHYSICS

179

Philoponus says, is inconsistent not only with the Christian doctrine of

creation, but also with Aristotle’s own opinion that nothing could traverse

through more than a Wnite number of temporal periods. For if the world

had no beginning, then it must have endured through an inWnite number

of years, and worse still, through 365 times an inWnite number of days

(book 5, frag. 132).

In his commentary on Aristotle’s Physics (641. 13 V.) Philoponus attacked

the dynamics of natural and violent motion. Aristotle encountered a

diYculty in explaining the movement of projectiles. If I throw a stone,

what makes it move upwards and onwards when it leaves my hand? Its

natural motion is downwards, and my hand is no longer in contact with it

to impart its violent motion upwards. Aristotle’s answer was that the stone

was pushed on, at any particular point, by the air immediately behind it; an

answer that Philoponus subjected to justiWed ridicule. Philoponus’ own

answer was that the continued motion was due to a force within the

projectile itself—an immaterial kinetic force impressed upon it by the

thrower, to which later physicists gave the technical term ‘impetus’. The

theory of impetus remained inXuential until Galileo and Newton proposed

the startling principle that no moving cause, external or internal, was

needed to explain the continued motion of a moving body.

Philoponus applied his theory of impetus throughout the cosmos. The

heavenly bodies, for instance, travel in their orbits not because they have

souls, but because God gave them the appropriate impetus when he

created them. Though the notion of impetus has been superannuated by

the discovery of inertia, it was itself a great improvement on its Aristotelian

predecessor. It enabled Philoponus to dispense with the odd mixture of

physics and psychology in Aristotle’s astronomy.

Natural Philosophy in the Thirteenth Century

Nonetheless, Aristotle’s natural philosophy remained inXuential for cen-

turies to come. Both in Islamic and in Latin philosophy the study of nature

was carried out within the framework of commentaries on Aristotle’s

works, especially the Physics. Individuals such as Robert Grosseteste and

Albert the Great extended Aristotelian science with detailed studies of

particular scientiWc topics; but the general conceptual framework

PHYSICS

180

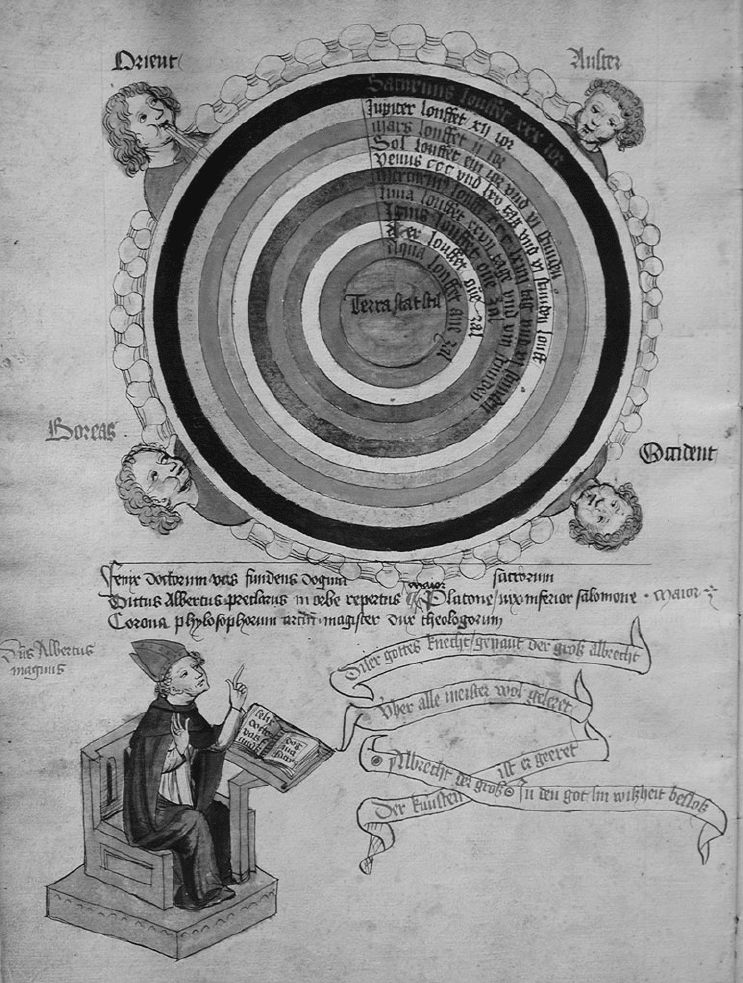

Albert the Great teaching astronomy, from a MS in the University library of Salzburg

PHYSICS

181