Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the philosophy of wittgenstein

374

enchanted by the sound of the words. But I haven’t the faintest idea what they

mean. If understanding and meaning were processes, they would have to accom-

pany private utterances as well as public utterances. So if the processes involved

were some kind of inner utterance, we would be set off on an endless quest for

the real understanding.

Some philosophers have thought that understanding was a mental process in

rather a different sense. They have conceived the mind as a hypothetical mechan-

ism postulated to explain the observable intelligent behaviour of human beings. If

one conceives the mind in this way one thinks of a mental process, not as some-

thing comparable to reciting the ABC in one’s head, but as a process occurring in

the special mental machinery. The process on this view is a mental process because

it takes place in a medium which is not physical; the machinery operates according

to its own mysterious laws, within a structure which is not material but spiritual;

it is not accessible to empirical investigation, and could not be discovered, say, by

opening up the skull of a thinker.

Such processes need not, on this view, be accessible even to the inner eye of

introspection: the mental mechanism may operate too swiftly for us to be able to

follow all its movements, like the pistons of a railway engine or the blades of a

lawn mower. But we may feel that if only we could sharpen our faculty for

introspection, or somehow get the mental machinery to run in slow motion, we

might be able actually to observe the processes of meaning and understanding.

According to one version of the mental-mechanism doctrine, understanding

the meaning of a word consists in calling up an appropriate image in connection

with it. In general, of course, we have no such experience when we use a word

and in the case of many words (such as ‘the’ ‘if’ ‘impossible’ ‘one million’) it is

difficult even to suggest what would count as an appropriate image. But let us

waive these points, allow that perhaps we can have images in our mind without

noticing that we do, and consider only the kind of word for which this account

sounds most plausible, such as colour words. We may examine the suggestion

that in order to understand the order ‘Bring me a red flower’ one must have a red

image in mind, and that it is by comparison with this image that one ascertains

which flower to bring. Once we stop to think, we realize this cannot be right:

otherwise how could one obey the order ‘imagine a red patch?’ Whatever problems

there are about identifying the redness of the flower recur with identifying the

redness of the patch.

It is of course true that when we talk, mental images often do pass through our

minds. But it is not they which confer meanings on the words we use. It is rather

the other way round: the images are like the pictures illustrating a text in the

book. In general it is the text which tells us what the pictures are of, not the

pictures which tell us what the words of the text mean.

In this way Wittgenstein examines, and makes us reject, various processes

which might be thought of as the process of meaning. In fact, meaning and

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM374

the philosophy of wittgenstein

375

understanding are not processes at all. We are misled by grammar. Because the

surface grammar of the verbs ‘mean’ and ‘understand’ resembles that of verbs like

‘say’ and ‘breathe’, we expect to find processes which correspond to them. When

we cannot find an empirical process we postulate an incorporeal process.

There is another metaphysical doctrine which is closely associated with the idea

that meaning is a mental process: it is the idea that naming is a mental act. This

idea is the target of Wittgenstein’s criticism of the notion of a private language,

or more precisely, of the notion of private definition.

Wittgenstein’s discussion of language-games makes clear that not all words are

names; but even naming is not as simple as it appears. To name something it is

not sufficient to confront it and utter a sound: the asking and giving of names is

something which can be done only in the context of a language-game. This is so

even in the relatively simple case of naming a material object: matters are much

more complicated when we consider the names of mental events and states, such

as sensations and thoughts.

Wittgenstein considers at length the way in which a word such as ‘pain’ func-

tions as the name of a sensation. We are tempted to think that for each person

‘pain’ acquires its meaning by being correlated by him with his own private,

incommunicable sensation. This temptation must be resisted: Wittgenstein showed

that no word could acquire meaning in this way. One of his arguments runs as

follows.

Suppose that I wish to baptize a private sensation of mine with the name ‘S’.

I fix my attention on the sensation in order to correlate the name with it.

What does this achieve? When next I want to use the name ‘S’, how will I know

whether I am using it rightly? Since the sensation it is to name is supposed to

be a private one, no one else can check up on my use of it. But neither can I do

so for myself. Before I can check up on whether the sentence ‘This is S again’

is true, I need to know what the sentence means. How do I know that what I

now mean by ‘S’ was what I meant when I christened the first sensation ‘S’.

Can I appeal to memory? No, for to do so I must call up the right memory,

the memory of S; and in order to do that I must already know what ‘S’ means.

There is in the end no check on my use of ‘S’, no way of making out a differ-

ence between correct and incorrect use of it. That means that talk of ‘correctness’

is out of place, and shows that the private definition I have given myself is no

real definition.

The conclusion of Wittgenstein’s attack on private definition is that there

cannot be a language whose words refer to what can only be known to the

individual speaker of the language. The language-game with the English word

‘pain’ is not a private language, because, whatever philosophers may say, other

people can very often know when a person is in pain. It is not by any solitary

definition that ‘pain’ becomes the name of a sensation: it is rather by forming

part of a communal language-game. For instance, a baby’s cry is a spontaneous,

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM375

the philosophy of wittgenstein

376

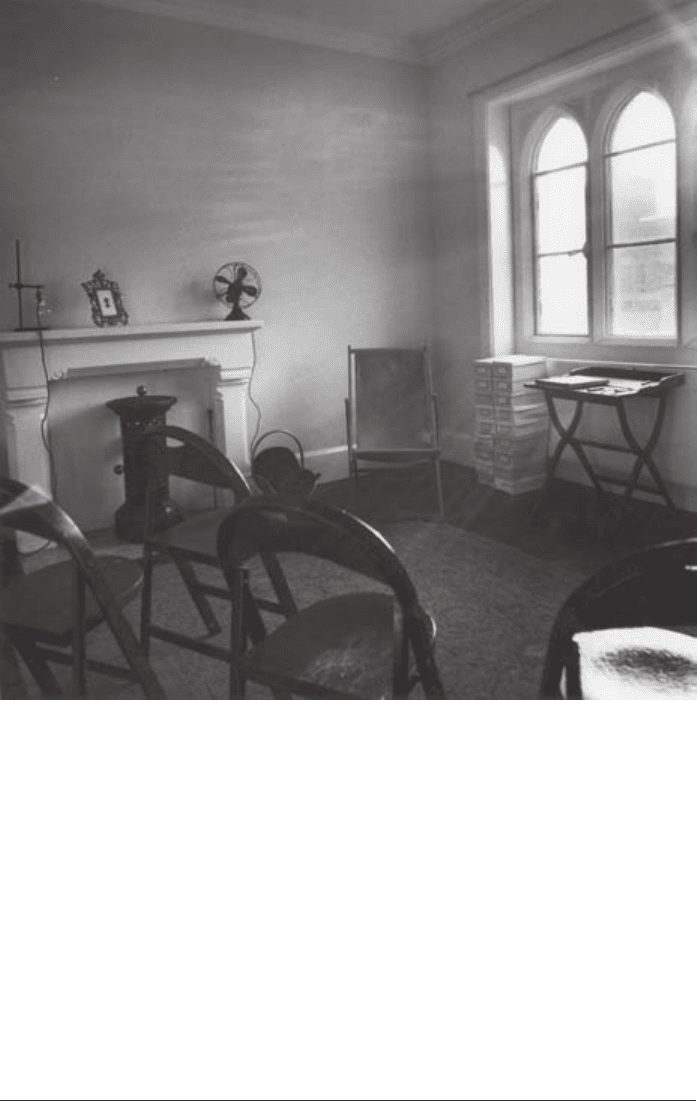

Figure 46 Wittgenstein’s teaching room in Trinity College, Cambridge.

(© Wittgenstein Archive)

pre-linguistic expression of pain; gradually the child is trained by her parents to

replace this with the conventional, learned expression of pain through language.

Thus pain-language is grafted on to the natural expression of pain.

What is the point of the private language argument? Who is Wittgenstein

arguing against? The short answer is that he is arguing against the author of the

Tractatus, who had given countenance to solipsism. Solipsism is the doctrine

‘Only I exist’. In the Tractatus Wittgenstein wrote:

what solipsism means is quite correct, only it cannot be said, but it shows itself.

That the world is my world shows itself in the fact that the limits of language (the

language which I understand) mean the limits of my world.

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM376

the philosophy of wittgenstein

377

Gradually, as Wittgenstein’s philosophy developed, he came to think that, even as

a piece of unsayable philosophy, solipsism was a perversion of reality. The world

is my world only if language is my language: a language created by my own link-

age of words to the world. But language is not my language; it is our language.

The private language argument shows that no purely private definitions could

create a language. The home of language is not the inner world of the solipsist,

but the life of the human community. Even the word ‘I’ only has meaning as a

word in our common language.

But the scope of the private language argument extends much further than

the refutation of Wittgenstein’s earlier self. Descartes, in expressing his philo-

sophical doubt, assumes that language has meaning while the existence of the

body is uncertain. Hume thought it possible for thoughts and experiences to be

recognized and classified while the question of the existence of the external

world is held in suspense. Mill and Schopenhauer, in their different ways,

thought that a man could express the contents of his mind in language while

questioning the existence of other minds. All of these suppositions entail the

possibility of a private language. And all of these suppositions are essential to the

structure of the philosophies in question. Common to both empiricism and

idealism is the doctrine that the mind has no direct knowledge of anything but

its own contents. The history of both movements shows that they lead in the

direction of solipsism. Wittgenstein’s attack on private definition refutes solipsism

by showing that the possibility of the very language in which it is expressed

depends on the existence of the public and social world. The refutation of

solipsism carries over into a refutation of the empiricism and idealism which

inexorably involve it.

Wittgenstein did not wish to replace empiricism and idealism with a differ-

ent philosophical system; his later philosophy was the very reverse of systematic.

This does not mean that it lacked method, or rigour. It means rather that there

was no part of philosophy which had primacy over any other part. One could start

philosophizing at any point, and leave off the treatment of one problem to take

up the treatment of another. Philosophy had no foundations, and did not provide

foundations for other disciplines. Philosophy was not a house, nor a tree, but

a web.

The real discovery is the one that makes me capable of stopping doing philosophy

when I want to. – The one that gives philosophy peace, so that it is no longer

tormented by questions which bring itself into question. – Instead, we now demon-

strate a method, by examples; and the series of examples can be broken off. Prob-

lems are solved (difficulties eliminated) not a single problem.

Wittgenstein believed that he had completely transformed the nature of phi-

losophy. Certainly, his philosophy is very different from the great systems of the

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM377

the philosophy of wittgenstein

378

nineteenth century which presented philosophy as a super-science. But his thought

is not as discontinuous with the great tradition of Western philosophy as he some-

times seems to have believed. Of course Wittgenstein was hostile to metaphysics,

to the pretensions of rationalistic philosophy to prove the existence of God, the

immortality of the soul, and to go far beyond the bounds of experience. He was

hostile to that; but then so was Kant. Wittgenstein was insistent that all our

intellectual inquiries depend for the possibility of their existence on all kinds of

simple, natural, inexplicable, original impulses of the human mind; but so was

Hume. Wittgenstein was insistent that philosophy was something which each

person must do for himself, and involves the will more than the intellect; but

so was Descartes. Wittgenstein was anxious that the philosopher should distin-

guish between parts of speech which grammarians lump together; within the

broad category of verbs, for example, the philosopher has to distinguish between

processes, conditions, dispositions, states, and so on. But almost word for word

the distinctions which Wittgenstein makes correspond to distinctions made by

Aristotle and his followers.

Though Wittgenstein, throughout his life, made a sharp distinction between

philosophy and science, his philosophy has implications for other disciplines.

Philosophy of mind, for instance, is important for empirical psychology. It is not

that the philosopher is in possession of information which the psychologist lacks,

or has explored areas of the psyche where no psychologist has ventured. What the

philosopher can clarify is the psychologists’ starting point, namely, the everyday

concepts we use in describing the mind, and the criteria on the basis of which

mental powers, states, and processes are attributed to people.

Philosophy of mind has often been a battleground between dualists and beha-

viourists. Dualists regard the human mind as independent of the body and separ-

able from it; for them the connection between the two is a contingent and not a

necessary one. Behaviourists regard reports of mental acts and states as disguised

reports of pieces of bodily behaviour, or at best of tendencies to behave bodily in

certain ways. Wittgenstein rejected both dualism and behaviourism. He agreed with

dualists that particular mental events could occur without accompanying bodily

behaviour; he agreed with behaviourists that the possibility of describing mental

events at all depends on their having, in general, an expression in behaviour. On

his view, to ascribe a mental event or state to someone is not to ascribe to her any

kind of bodily behaviour; but such ascription can only sensibly be made to beings

which have the capability of behaviour of the appropriate kind.

Wittgenstein was hostile not only to the behaviourist attempt to identify the

mind with behaviour, but also to the materialist attempt to identify the mind with

the brain. Human beings and their brains are physical objects; minds are not.

This is not a metaphysical claim: to deny that a mind has a length or breadth or

location is not to say that it is a spirit. Materialism is a grosser philosophical error

than behaviourism because the connection between mind and behaviour is a more

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM378

the philosophy of wittgenstein

379

intimate one than that between mind and brain. The link between mind and

behaviour is something prior to experience: that is to say, the concepts which we

use in describing the mind and its contents have behavioural criteria for their

application. But the connection between mind and brain is a contingent one,

discoverable by empirical science. Aristotle’s grasp of the nature of mind will

stand comparison with that of many a contemporary psychologist; but he had a

wildly erroneous idea of the relationship of the mind with the brain, which he

believed to be an instrument to cool the blood.

Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mind is closer to that of Aristotle than it is to

contemporary materialist psychology. In one of his most characteristic, and most

striking remarks, he goes so far as to entertain the possibility that some of our

mental activities may lack any correlate in the brain.

No supposition seems to me more natural than that there is no process in the brain

correlated with associating or with thinking; so that it would be impossible to read

off thought-processes from brain-processes. I mean this: if I talk or write there is,

I assume, a system of impulses going out from my brain and correlated with my

spoken or written thoughts. But why should the system continue further in the direc-

tion of the centre? Why should this order not proceed, so to speak, out of chaos?

It is perfectly possible that certain psychological phenomena cannot be identified

physiologically, because physiologically nothing corresponds to them. Why should

there not be a psychological regularity to which no physiological regularity cor-

responds? If this upsets our concepts of causality, then it is high time they were upset.

Here Wittgenstein makes a frontal attack on the scientism characteristic of our

age: the assumption that there must be physical counterparts of mental phenom-

ena. He is not defending any kind of dualism or spiritualism: what does the

associating, thinking, and remembering is not a spiritual substance, but a bodily

human being. But he does envisage as a possibility a pure Aristotelian soul, or

entelechy, which operates with no material vehicle: a formal and final cause to

which there corresponds no mechanistic efficient cause.

In his later years, in the thoughts published posthumously in On Certainty,

Wittgenstein became interested in the propositions which make up the world-view

of a society or individual. Any language-game presupposes an activity which is

part of a form of life. To imagine a language, Wittgenstein says, is to imagine a

form of life. To accept the rules of a language is to agree with others in a form of

life. The ultimate given in philosophy is not an inner basis of private experience:

it is the forms of life within which we pursue our activities and think our thoughts.

Forms of life are the datum, which philosophy cannot call into question, but

which any philosophical inquiry itself presupposes. What, then, is a form of life?

The paradigm of a difference between forms of life is the difference between the

life of two different species of animals – animals with different ‘natural histories’,

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM379

the philosophy of wittgenstein

380

to use an expression beloved by Wittgenstein. Lions have a different form of life

from humans; for that reason, if a lion could speak, we could not understand him.

But there can be differences between forms of life within the human species,

too. Human beings share a form of life if they share a Weltbild, a picture of the

world. A world-picture is neither true nor false. Disputes about truth are possible

only within a world-picture, between disputants who share the same form of life.

When one person denies what is part of the world-picture of another this may

sometimes seem like lunacy, but sometimes it reflects a very deep difference of

culture. If someone doubts that the world has existed before he was born we

might think him mad: but in a certain culture might not a king be brought up in

the belief that the world began with him?

Our world-picture includes propositions which look like scientific propositions:

for instance ‘water boils at 100 centigrade’, ‘there is a brain inside my skull’.

Others look like everyday empirical propositions: ‘motor cars don’t grow out of

the earth’ or ‘the earth has existed for a long time’. But these propositions are

not learnt by experience. When someone more primitive is persuaded to accept

our world-picture, this is not by our giving him grounds to prove the truth of

those propositions; rather, we convert him to a new way of looking at the world.

The role of such propositions is quite different from those of axioms in a system:

it is not as if they were learnt first and then conclusions were drawn from them.

Children do not learn them: they as it were swallow them down with what they

learn. When first we begin to believe anything, we believe not a single proposition,

but a whole system; and the system is not a set of axioms, a point of departure, so

much as the whole element in which all arguments have their life.

In discussing the propositions which make up our world-picture, Wittgenstein

recognized that he was addressing the same problems as were posed by Newman

in the Grammar of Assent: how is it possible to have unshakeable certainty which

is not based on evidence. But he disapproved of the purpose for which Newman

undertook his investigations, namely to prove the reasonableness of Christianity.

Wittgenstein thought that Christians were obviously not reasonable; they based

enormous convictions on flimsy evidence. But this did not mean that they were

unreasonable; it meant that they should not treat faith as a matter of reasonability

at all. In this, Wittgenstein was much closer to Kierkegaard than to Newman.

Wittgenstein was hostile to the idea that there was a branch of philosophy,

natural theology, which could prove the reasonableness of belief in God. Philo-

sophy, he thought, could not give any meaning to life; the best it could provide

would be a form of wisdom. He frequently contrasts the emptiness of wisdom

with the vigour of faith: faith is a passion, but wisdom is cold grey ash, covering

up the glowing embers.

But though only faith, and not philosophy, can give meaning to life, that does

not mean that philosophy has no rights whatever within the terrain of faith. Faith

may involve talking nonsense, and philosophy may point out that it is nonsense.

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM380

the philosophy of wittgenstein

381

Wittgenstein, who once said ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be

silent’, later said ‘Don’t be afraid of talking nonsense.’ But he went on to add:

You must keep an eye on your nonsense.

It is philosophy that keeps an eye on the nonsense. First, it points out that the

nonsense is nonsense: faith is no more able than philosophy, to say what is the

meaning of life. Here Wittgenstein’s old distinction between saying and showing

reappears. It does not matter, he thought, if the Gospels are false. That is not a

remark which could be made about something which was a saying, since the most

important fact about sayings is that they are either true of false, and it matters

greatly which. Secondly, even if religious utterances are not sayings, philosophy

still has a critical role in their regard. Above all, it can distinguish faith from super-

stition. The attempt to make religion appear reasonable seemed to Wittgenstein

to be the extreme of superstition.

AIBC22 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM381

afterword

382

AFTERWORD

Anyone looking back over the long history of philosophy is bound to wonder:

does philosophy get anywhere? Have philosophers, for all their efforts over the

centuries, actually learnt anything? Voltaire, talking of metaphysicians, wrote:

They are like minuet dancers, who, being dressed to the greatest advantage, make a

couple of bows, move through the room in the finest attitudes, display all their

graces, are in perpetual motion without advancing a step, and finish at the identical

point from which they set out.

In our own time, Wittgenstein wrote:

You always hear people say that philosophy makes no progress and that the same

philosophical problems which were already preoccupying the Greeks are still troub-

ling us today. But people who say that do not understand the reason why it has to

be so. The reason is that our language has remained the same and always introduces

us to the same questions. As long as there is a verb ‘be’ which seems to work like

‘eat’ and ‘drink’; as long as there are adjectives like ‘identical’, ‘true’, ‘false’, ‘pos-

sible’; as long as people speak of the passage of time and the extent of space, and so

on; as long as all this happens people will always run up against the same teasing

difficulties and will stare at something which no explanation seems to remove. I read

‘philosophers are no nearer to the meaning of “reality” than Plato got’. What an

extraordinary thing! How remarkable that Plato could get so far! Or that we have

not been able to get any further! Was it because Plato was so clever?

On Wittgenstein’s view, it seems, there cannot be real progress in philosophy;

philosophy is not like a science which progresses by adding, age by age, new

layers of information upon foundations laid by previous generations. Certainly,

any reader of this book will have observed how certain philosophical problems

seem to remain constant, and how philosophers in later ages return again and

again to themes and theories of their predecessors.

If philosophy makes no progress at all, then there seems little point in reading

the history of philosophy. It is not surprising, therefore, that in his History of

AIBD01 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM382

afterword

383

Western Philosophy Bertrand Russell took up a position different from that of

Voltaire and Wittgenstein. There were, he maintained, instances where philosophy

had reached definitive answers to certain questions. He gave as one example the

ontological argument.

This, as we have seen, was invented by Anselm, rejected by Thomas Aquinas,

accepted by Descartes, refuted by Kant, and reinstated by Hegel. I think it may be

said quite decisively that as a result of analysis of the concept ‘existence’ modern

logic has proved this argument invalid.

The ontological argument is a two-edged instance to cite. Its history does indeed

show that there can be developments in philosophy: Anselm brought off the feat

of inventing an argument that had not occurred to any previous philosopher. On

the other hand, if the best example of philosophical progress is a case where later

philosophers show up the fallacy of an earlier philosopher, it confirms the view

that philosophy is only of use against philosophers. Worst of all, quite recently

some contemporary philosophers, using more sophisticated forms of modern

logic than were available to Russell, have claimed to reinstate the argument which

he thought decisively refuted.

None the less, on this issue I believe Russell was closer to the truth than

Wittgenstein. It is true that philosophy does not progress by making regular

additions to a quantum of information; but philosophy offers not information,

but understanding, and there are certain things which philosophers of the present

day understand which even the greatest philosophers of earlier generations failed

to understand. Even if we accept Wittgenstein’s view that philosophy is essentially

the clarification of language, there is plenty of room for progress. For instance,

philosophers clarify language by distinguishing between different senses of words;

and once a distinction has been made, future philosophers have to take account

of it in their deliberations.

Take, as an example, the issue of free-will. Once a distinction has been made

between liberty of indifference and liberty of spontaneity, the question ‘do humans

enjoy freedom of the will?’ has to be answered in a way which takes account of

the distinction. Even someone who believes that the two kinds of liberty coincide

has to provide arguments to show this; he cannot simply ignore the distinction

and hope to be taken seriously as a philosopher.

It often happens that after a philosophical question has been clarified by the

drawing of relevant distinctions, one of the new questions which emerge from the

analysis turns out not to be a philosophical question at all, but a question to be

solved by some other discipline. In such a case, intellectual progress has been

made, but the progress will not appear to be progress in philosophy. This process

can be illustrated by reference to the question of innate ideas.

As the reader will remember, there was a keen debate in the seventeenth cen-

tury about the question: which of our ideas are innate, and which are acquired?

AIBD01 22/03/2006, 11:10 AM383