Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

x

PREFACE

Fifty-two years ago Bertrand Russell wrote a one-volume History of Western Philo-

sophy, which is still in demand. When it was suggested to me that I might write a

modern equivalent, I was at first daunted by the challenge. Russell was one of the

greatest philosophers of the century, and he won a Nobel Prize for Literature: how

could anyone venture to compete? However, the book is not generally regarded

as one of Russell’s best, and he is notoriously unfair to some of the greatest

philosophers of the past, such as Aristotle and Kant. Moreover, he operated with

assumptions about the nature of philosophy and philosophical method which

would be questioned by most philosophers at the present time. There does indeed

seem to be room for a book which would offer a comprehensive overview of the

history of the subject from a contemporary philosophical viewpoint.

Russell’s book, however inaccurate in detail, is entertaining and stimulating

and it has given many people their first taste of the excitement of philosophy. I

aim in this book to reach the same audience as Russell: I write for the general

educated reader, who has no special philosophical training, and who wishes to

learn the contribution that philosophy has made to the culture we live in. I have

tried to avoid using any philosophical terms without explaining them when they

first appear. The dialogues of Plato offer a model here: Plato was able to make

philosophical points without using any technical vocabulary, because none existed

when he wrote. For this reason, among others, I have treated several of his

dialogues at some length in the second and third chapters of the book.

The quality of Russell’s writing which I have been at most pains to imitate is

the clarity and vigour of his style. (He once wrote that his own models as prose

writers were Baedeker and John Milton.) A reader new to philosophy is bound to

find some parts of this book difficult to follow. There is no shallow end in

philosophy, and every novice philosopher has to struggle to keep his head above

water. But I have done my best to ensure that the reader does not have to face

any difficulties in comprehension which are not intrinsic to the subject matter.

It is not possible to explain in advance what philosophy is about. The best way

to learn philosophy is to read the works of great philosophers. This book is meant

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM10

xi

to show the reader what topics have interested philosophers and what methods

they have used to address them. By themselves, summaries of philosophical doc-

trines are of little use: a reader is cheated if merely told a philosopher’s conclu-

sions without an indication of the methods by which they were reached. For this

reason I do my best to present, and criticize, the reasoning used by philosophers

in support of their theses. I mean no disrespect by engaging thus in argument with

the great minds of the past. That is the way to take a philosopher seriously: not to

parrot his text, but to battle with it, and learn from its strengths and weaknesses.

Philosophy is simultaneously the most exciting and the most frustrating of

subjects. Philosophy is exciting because it is the broadest of all disciplines, exploring

the basic concepts which run through all our talking and thinking on any topic

whatever. Moreover, it can be undertaken without any special preliminary training

or instruction; anyone can do philosophy who is willing to think hard and follow

a line of reasoning. But philosophy is also frustrating, because, unlike scientific or

historical disciplines, it gives no new information about nature or society. Philo-

sophy aims to provide not knowledge, but understanding; and its history shows how

difficult it has been, even for the very greatest minds, to develop a complete and

coherent vision. It can be said without exaggeration that no human being has yet

succeeded in reaching a complete and coherent understanding even of the language

we use to think our simplest thoughts. It is no accident that the man whom many

regard as the founder of philosophy as a self-conscious discipline, Socrates, claimed

that the only wisdom he possessed was his knowledge of his own ignorance.

Philosophy is neither science nor religion, though historically it has been en-

twined with both. I have tried to bring out how in many areas philosophical

thought grew out of religious reflection and grew into empirical science. Many

issues which were treated by great past philosophers would nowadays no longer

count as philosophical. Accordingly, I have concentrated on those areas of their

endeavour which would still be regarded as philosophical today, such as ethics,

metaphysics, and the philosophy of mind.

Like Russell I have made a personal choice of the philosophers to include in

the history, and the length of time to be devoted to each. I have not, however,

departed as much as Russell did from the proportions commonly accepted in the

philosophical canon. Like him, I have included discussions of non-philosophers

who have influenced philosophical thinking; that is why Darwin and Freud appear

on my list of subjects. I have devoted considerable space to ancient and medieval

philosophy, though not as much as Russell, who at the mid-point of his book had

not got further than Alcuin and Charlemagne. I have ended the story at the time

of the Second World War, and I have not attempted to cover twentieth-century

continental philosophy.

Again like Russell, I have sketched in the social, historical, and religious back-

ground to the lives of the philosophers, at greater length when treating of remote

periods and very briefly as we approach modern times.

preface

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM11

xii

I have not written for professional philosophers, though of course I hope that

they will find my presentation accurate, and will feel able to recommend my book

as background reading for their students. To those who are already familiar with

the subject my writing will bear the marks of my own philosophical training,

which was first in the scholastic philosophy which takes its inspiration from the

Middle Ages, and then in the school of linguistic analysis which has been domin-

ant for much of the present century in the English-speaking world.

My hope in publishing this book is that it may convey to those curious about

philosophy something of the excitement of the subject, and point them towards

the actual writings of the great thinkers of the past.

I am indebted to the editorial staff at Blackwells, and to Anthony Grahame, for

assistance in the preparation of the book; and to three anonymous referees who

made helpful suggestions for its improvement. I am particularly grateful to my

wife, Nancy Kenny, who read the entire book in manuscript and struck out many

passages as unintelligible to the non-philosopher. I am sure that my readers will

share my gratitude to her for sparing them unprofitable toil.

January 1998

I am grateful to Dr D. L. Owen of the University of Minnesota and Dr I. J. de

Kreiner of Buenos Aires who pointed out a number of small errors in the first

edition of this work.

January 2006

preface

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM12

xiii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Plates

Between pages 208 and 209

1 Socrates drinking hemlock

2 Plato’s Academy

3 Aristotle presenting his works to Alexander

4 Temperance and Intemperance

5 The title page of a fifteenth-century manuscript translation of

Aristotle’s History of Animals

6 Lucretius’ De rerum natura

7 Saint Catherine of Alexandria disputing before the pagan

emperor Maxentius

8 Aristotle imparting instruction to Averroes

9 Saint Thomas Aquinas introducing Saints Francis and Dominic

to Dante

10 The intellectual soul being divinely infused into the human body

11 Aquinas triumphant over Plato

12 Machiavelli’s austere apartment

13 Philosophy as portrayed by Raphael on the ceiling of the

Stanza della Segnatura

14 Gillray’s cartoon of the radical Charles James Fox

15 Ford Madox Brown’s painting Work

16 A portrait of Wittgenstein by Joan Bevan

Figures

1 Pythagoras in Raphael’s School of Athens 3

2 Parmenides and Heraclitus as portrayed by Raphael in the

School of Athens 13

3 The temple of Concord in Agrigento 17

4 Aerial view of the Athenian Acropolis 23

5 A herm of Socrates bearing a quotation from the Crito 32

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM13

xiv

6 Medallion of Plato from the frieze in the Upper Reading Room

of the Bodleian Library, Oxford 39

7 The cardinal virtues of courage, wisdom, and temperance by Raphael 47

8 Plato’s use of animals to symbolise the different parts of the

human soul (by Titian) 52

9 Aristotle, painted by Justus of Ghent 64

10 ‘Sacred and Profane Love’ by Titian 75

11 A Roman copy of a Hellenistic portrait bust of Alexander the Great 77

12 Athena introducing a soul into a body 86

13 A modern reconstruction of the schools of Athens 92

14 A fifth-century mosaic in Gerasa representing the city of Alexandria 105

15 Saint Augustine represented on a winged fifteenth-century

altarpiece 116

16 John Scotus Eriugena disputing with a Greek abbot Theodore 126

17 Sculpture showing Abelard with Héloïse 134

18 Aristotle’s Metaphysics, showing the Philosopher surrounded by

Jewish, Muslim, and Christian followers 141

19 Roundel of Duns Scotus 166

20 William Ockham 173

21 John Wyclif 180

22 The title page of Thomas More’s Utopia 191

23 Bronze relief of Giordano Bruno lecturing 200

24 The title page of Bacon’s Instauratio Magna 203

25 Portrait of Descartes by Jan Baptist Weenix 209

26 Descartes’ sketch of the mechanism whereby pain is felt by

the soul 217

27 Portrait of Hobbes by Jan. B. Gaspars 224

28 Title page of Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding 235

29 Portrait of Baruch Spinoza by S. van Hoogstraten 244

30 Leibniz showing ladies of the court that no two leaves are

exactly alike 250

31 David Hume, in a medallion by J. Tassie 257

32 Allan Ramsay’s portrait of J. J. Rousseau 269

33 Immanuel Kant 277

34 Title page of Kant’s first Critique 287

35 The architect of the universe in Blake’s Ancient of Days 294

36 Portrait of Hegel 300

37 Jeremy Bentham’s ‘auto-icon’ 310

38 Portrait of John Stuart Mill, by G. F. Watts 315

39 A cartoon by Wilhelm Busch of Schopenhauer with his poodle 321

40 Photograph of Charles Darwin 334

41 Photograph of Cardinal John Henry Newman 340

list of illustrations

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM14

xv

42 Freud’s sketch of the Ego and the Id 346

43 A page of Frege’s derivation of arithmetic from logic 355

44 Bertrand Russell as a young man 361

45 Wittgenstein’s identity card as an artilleryman in the Austrian

army in 1918 366

46 Wittgenstein’s teaching room in Trinity College, Cambridge 376

list of illustrations

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM15

xvi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the following for permission to

reproduce copyright material:

T. S. Eliot: for an excerpt from Part IV of ‘The Dry Salvages’ from Four Quartets,

copyright © 1941 by T. S. Eliot and renewed 1969 by Esme Valerie Eliot, and

for an excerpt from Part II of ‘Little Gidding’ from Four Quartets, copyright ©

1943 by T. S. Eliot and renewed 1971 by Esme Valerie Eliot, to Harcourt Brace

& Company and Faber & Faber Ltd. (Reprinted by Faber in Collected Poems

1909–1962 by T. S. Eliot.)

W. B. Yeats: for lines from ‘Among School Children’ from The Collected Works of

W. B. Yeats, Volume 1: The Poems, revised and edited by Richard J. Finneran,

copyright © 1928 by Macmillan Publishing Company, renewed © 1956 by Georgie

Yeats, to A. P. Watt Ltd., on behalf of Michael Yeats, and Scribner, a division of

Simon & Schuster.

The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions in the above list and would

be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in the

next edition or reprint of this book.

AIBA01 22/03/2006, 10:05 AM16

philosophy in its infancy

1

I

PHILOSOPHY

IN ITS INFANCY

The earliest Western philosophers were Greeks: men who spoke dialects of the

Greek language, who were familiar with the Greek poems of Homer and Hesiod,

and who had been brought up to worship Greek Gods like Zeus, Apollo, and

Aphrodite. They lived not on the mainland of Greece, but in outlying centres of

Greek culture, on the southern coasts of Italy or on the western coast of what is

now Turkey. They flourished in the sixth-century bc, the century which began

with the deportation of the Jews to Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar and ended

with the foundation of the Roman Republic after the expulsion of the young

city’s kings.

These early philosophers were also early scientists, and several of them were

also religious leaders. In the beginning the distinction between science, religion,

and philosophy was not as clear as it became in later centuries. In the sixth

century, in Asia Minor and Greek Italy, there was an intellectual cauldron in

which elements of all these future disciplines fermented together. Later, religious

devotees, philosophical disciples, and scientific inheritors could all look back to

these thinkers as their forefathers.

Pythagoras, who was honoured in antiquity as the first to bring philosophy to

the Greek world, illustrates in his own person the characteristics of this early

period. Born in Samos, off the Turkish coast, he migrated to Croton on the toe

of Italy. He has a claim to be the founder of geometry as a systematic study (see

Figure 1). His name became familiar to many generations of European school-

children because he was credited with the first proof that the square on the long

side of a right-angled triangle is equal in area to the sum of the squares on the

other two sides. But he also founded a religious community with a set of ascetic

and ceremonial rules, the best-known of which was a prohibition on the eating of

beans. He taught the doctrine of the transmigration of souls: human beings had

souls which were separable from their bodies, and at death a person’s soul might

migrate into another kind of animal. For this reason, he taught his disciples to

abstain from meat; once, it is said, he stopped a man whipping a puppy, claiming

AIBC01 22/03/2006, 10:35 AM1

philosophy in its infancy

2

to have recognized in its whimper the voice of a dear dead friend. He believed

that the soul, having migrated into different kinds of animal in succession, was

eventually reincarnated as a human being. He himself claimed to remember

having been, some centuries earlier, a hero at the siege of Troy.

The doctrine of the transmigration of souls was called in Greek ‘metempsy-

chosis’. Faustus, in Christopher Marlowe’s play, having sold his soul to the devil,

and about to be carried off to the Christian Hell, expresses the desperate wish

that Pythagoras had got things right.

Ah, Pythagoras’ metempsychosis, were that true

This soul should fly from me, and I be chang’d

Unto some brutish beast.

Pythagoras’ disciples wrote biographies of him full of wonders, crediting him

with second sight and the gift of bilocation, and making him a son of Apollo.

The Milesians

Pythagoras’ life is lost in legend. Rather more is known about a group of philo-

sophers, roughly contemporary with him, who lived in the city of Miletus in

Ionia, or Greek Asia. The first of these was Thales, who was old enough to

have foretold an eclipse in 585. Like Pythagoras, he was a geometer, though he

is credited with rather simpler theorems, such as the one that a circle is bisected

by its diameter. Like Pythagoras, he mingled geometry with religion: when he

discovered how to inscribe a right-angled triangle inside a circle, he sacrificed

an ox to the gods. But his geometry had a practical side: he was able to measure

the height of the pyramids by measuring their shadows. He was also interested in

astronomy: he identified the constellation of the little bear, and pointed out its

use in navigation. He was, we are told, the first Greek to fix the length of the year

as 365 days, and he made estimates of the sizes of the sun and moon.

Thales was perhaps the first philosopher to ask questions about the structure

and nature of the cosmos as a whole. He maintained that the earth rests on water,

like a log floating in a stream. (Aristotle asked, later: what does the water rest

on?) But earth and its inhabitants did not just rest on water: in some sense, so

Thales believed, they were all made out of water. Even in antiquity, people could

only conjecture the grounds for this belief: was it because all animals and plants

need water, or because the seeds of everything are moist?

Because of his theory about the cosmos Thales was called by later writers a

physicist or philosopher of nature (‘physis’ is the Greek word for ‘nature’). Though

he was a physicist, Thales was not a materialist: he did not, that is to say, believe

that nothing existed except physical matter. One of the two sayings which have

AIBC01 22/03/2006, 10:35 AM2

philosophy in its infancy

3

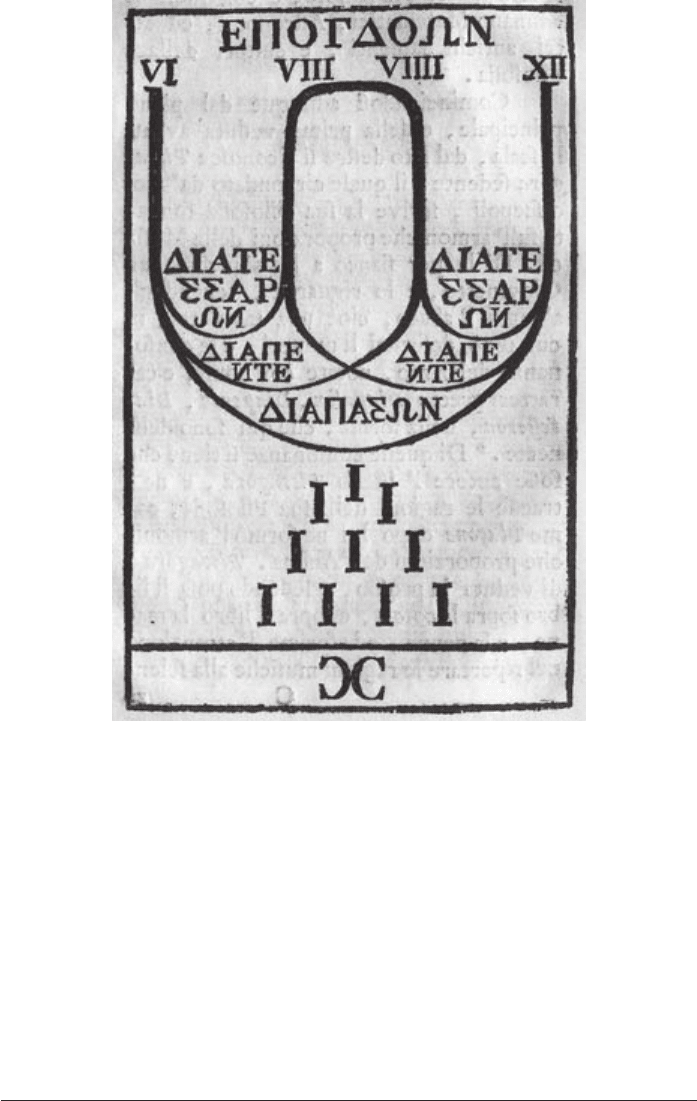

Figure 1 The Pythagoreans discovered the relationships between frequency and

pitch in the notes of the octave scale, as shown in this diagram held up for Pythagoras

in Raphael’s School of Athens.

(© Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts)

come down from him verbatim is ‘everything is full of gods’. What he meant is

perhaps indicated by his claim that the magnet, because it moves iron, has a soul.

He did not believe in Pythagoras’ doctrine of transmigration, but he did maintain

the immortality of the soul.

Thales was no mere theorist. He was a political and military adviser to King

Croesus of Lydia, and helped him to ford a river by diverting a stream. Foresee-

ing an unusually good olive crop, he took a lease on all the oil-mills, and made a

fortune. None the less, he acquired a reputation for unworldly absent-mindedness,

AIBC01 22/03/2006, 10:35 AM3