Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

three modern masters

344

He continued in practice in Vienna until the 1930s, and published a series of

highly readable books constantly modifying and refining his psychoanalytic the-

ories. Fear of Nazi persecution forced him to migrate to England in 1938, and he

died there at the beginning of the Second World War.

In his Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis Freud sums up psychoanalytic

theory in two fundamental premises: the first is that the greater part of our

mental life, whether of feeling, thought or volition, is unconscious; the second is

that sexual impulses, broadly defined, are supremely important not only as poten-

tial causes of mental illness but as the motor of artistic and cultural creation. If

the sexual element in the work of art and culture remains largely unconscious,

this is because socialization demands the sacrifice of basic instincts, which become

sublimated, that is to say, diverted from their original goals and channelled

towards socially desirable activities. But sublimation is an unstable state, and

untamed and unsatisfied sexual instincts may take their revenge through mental

illness and disorder.

The existence of the unconscious is revealed, Freud believes, in three ways:

through everyday trivial mistakes, through reports of dreams, and through the

symptoms of neurosis.

What Freud called ‘parapraxes’, but are nowadays known as Freudian slips, are

common episodes such as failure to recall names, slips of the tongue, and mislay-

ing of objects. Freud gives many examples. A professor at Vienna, in his inaugural

lecture, instead of saying, according to his script, ‘I have no intention of under-

rating the achievements of my illustrious predecessor’ said ‘I have every intention

of underrating the achievements of my illustrious predecessor.’ Some years after

the sinking of the liner Lusitania, a husband, asking his estranged wife to rejoin

him across the Atlantic, wrote ‘Come across on the Lusitania’, when he meant to

write ‘Come across on the Mauretania’. In each case Freud regards the slip as a

better guide to the man’s state of mind than the words consciously chosen.

Freud’s explanations of parapraxes are most convincing where – as in the cases

above – they reveal a state of mind of which the person was aware but merely

did not wish to express. This reveals no very deep level of unconscious inten-

tion. Matters are different when we come to the second method of tapping into

the unconscious: the analysis of dream reports. ‘The interpretation of dreams’,

Freud says, ‘is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the

mind.’ Dreams, he maintained, were almost always the fulfilment, in fantasy, of

a repressed wish. He admitted that comparatively few dreams are obvious repre-

sentations of the satisfaction of a wish, and many dreams, such as nightmares or

anxiety dreams, seem to be just the opposite. Freud dealt with this by insisting

that dreams were symbolic in nature, encoded by the dreamer in order to make

them appear innocuous. He distinguished between the manifest content of the

dream, which is what the dreamer reports, and the latent content of the dream,

which was the true meaning once the symbols had been decoded.

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:08 AM344

three modern masters

345

How is the decoding to be done? It is not difficult to give every dream a sexual

significance if one takes every pointed object like an umbrella to represent a penis,

and every capacious object like a handbag to represent the female genitals. But

Freud did not believe that it was possible to set up a dictionary which would

relate each symbol to what it symbolized. It was necessary to discover the signific-

ance of a symbolic dream item for the individual dreamer, and that could only be

done by exploring the associations which he attached to it in his own mind. Only

when that had been done could the dream be interpreted in a way which would

reveal the nature of the unconscious wish whose fulfilment the dream fantasized.

The third (though chronologically the first) method by which Freud purported

to explore the unconscious was by examining the symptoms of neurotic patients.

An Austrian undergraduate patient became obsessed with the (erroneous) thought

that he was too fat (ich bin zu dick). He became anorexic, and wore himself out

with mountain hiking. The explanation of the obsessional behaviour only became

clear when the patient mentioned that at the time his fiancée’s attention had been

distracted from him by the company of her English cousin Dick. The unconscious

purpose in slimming, Freud decided, had been to get rid of this Dick.

The unconscious motivations which surface in the psychopathology of everyday

life are commonly easily recognized and acknowledged by the person in question.

It is different with the significance of dreams and obsessional behaviour. This can

only be detected, Freud believed, by long sessions in which the analyst invites the

patient freely to associate ideas with the symbolic item or activity in question. The

analyst’s decoding of the symbolism is often initially rejected by the patient. For

a cure to be effective, the patient has to acknowledge the desire which, according

to the analyst, the decoded symbol reveals.

There is a certain circularity in Freud’s procedure for discovering the uncon-

scious. The existence of the unconscious is held to be proved by the evidence

of dreams and neurotic symptoms. But dreams and neurotic symptoms do not,

either on their face or as interpreted by the unaided patient, reveal the beliefs,

desires, and sentiments of which the unconscious is supposed to consist. The

criterion of success in decipherment is that the decoded message should accord

with the analyst’s notion of what the unconscious is like. But that notion was

supposed to derive from, and not to precede, the exploration of dreams and

symptoms.

The pattern to which the unconscious was to conform was laid out by Freud

in his theory of sexual development. Infantile sexuality begins with an oral stage,

in which physical pleasure is focused on the mouth. This is followed by an anal

stage, between one and three, and a ‘phallic’ stage, in which the child focuses on

its own penis or clitoris. Only at puberty does an individual’s sexuality perman-

ently focus on other persons. Freud, from an early stage in his career, regarded

neurotic symptoms as the result of the repression of sexual impulses during child-

hood, and saw neurotic characters as fixated at an early stage of their development.

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM345

three modern masters

346

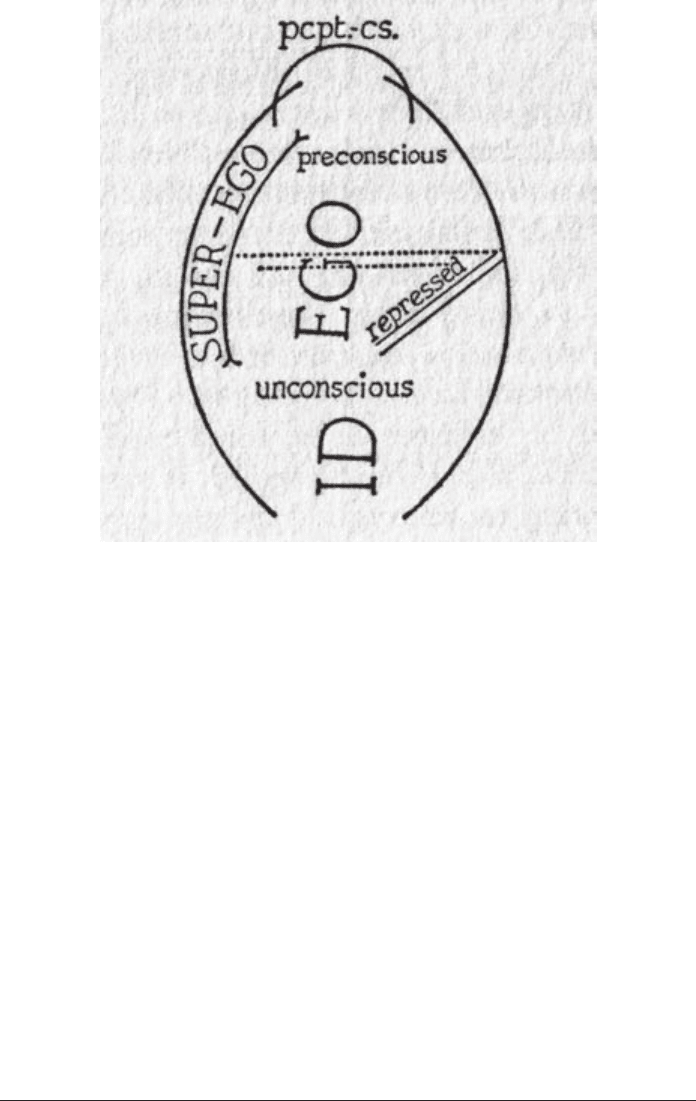

Figure 42 Freud’s own sketch of the Ego and the Id.

(Standard Edition, vol. XXII; by permission of Sigmund Freud Copyrights/

Paterson Marsh Ltd, London)

Freud attached great importance to the onset of the phallic stage. At that time,

he believed, a boy was sexually attracted to his mother, and began to resent his

father’s possession of her. But his hostility to his father leads to fear that his father

will retaliate by castrating him. So the boy abandons his sexual designs on his

mother, and gradually identifies with his father. This was the Oedipus complex, a

central stage in the emotional development in every boy, and also, in a modified

and never fully worked out version, of every girl. The recovery of Oedipal wishes,

and the history of their repression, became an important part of every analysis.

Towards the end of his life, Freud replaced the earlier dichotomy of conscious

and unconscious with a threefold scheme of the mind. ‘The mental apparatus,’ he

wrote, ‘is composed of an id which is the repository of the instinctual impulses, of

an ego which is the most superficial portion of the id and one which has been

modified by the influence of the external world, and of a superego which develops

out of the id, dominates the ego, and represents the inhibitions of instinct that

are characteristic of man.’

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM346

three modern masters

347

Freud claimed that the modification of his earlier theory had been forced on

him by the observation of his patients on the couch. Yet the mind, in this later

theory, closely resembles the tripartite soul of Plato’s Republic. The id corres-

ponds to the appetite, the source of the desires for food and sex. Freud’s id is

ruled by the pleasure principle and knows no moral code; similarly, Plato tells us

that if appetite is in control, pleasure and pain reign in one’s soul instead of law.

Both the id and the appetite contain contrary impulses perpetually at war. Some

of the desires of the appetite, and all those of the id, are unconscious and surface

only in dreams. Plato goes so far as to tell us that some of appetite’s dreams are

Oedipal: ‘In phantasy it will not shrink from intercourse with a mother or anyone

else, man, god, or brute, or from forbidden food or any deed of blood.’

Freud’s ego has much in common with Plato’s reasoning power. Reason is

the part of the soul most in touch with what is real, just as the ego is devoted to

the reality principle. Like reason, the ego has the task of controlling instinctual

desires, providing for their harmless release. Using one of Plato’s metaphors,

Freud compares the ego to a rider and the id to a horse. ‘The horse supplies the

locomotive energy, while the rider has the privilege of deciding on the goal and

guiding the powerful animal’s movement.’ Both Plato and Freud use hydraulic

metaphors to describe the mechanism of control, seeing id and appetite as a flow

of energy which can find normal discharge or be channelled into alternative

outlets. But Freud departs from Plato in regarding the damming up of such

energy as something which is likely to lead to disastrous results.

There remain Freud’s superego and the part of the Platonic soul called ‘tem-

per’. These are alike in being non-rational, punitive forces in the service of

morality, the source of shame and self-directed anger. For Freud, the superego is

an agency which observes, judges, and punishes the behaviour of the ego, partly

identical with the conscience, and concerned for the maintenance of ideals. It

upbraids and abuses the ego, just as Plato’s temper does. Superego and temper

are alike the source of ambition. However, the superego’s aggression is directed

exclusively at the ego, whereas the temper in a Platonic soul is directed at others

no less than oneself.

Both Freud and Plato regard mental health as harmony between the parts of

the soul, and mental illness as unresolved conflict between them. But only Freud

has a worked out theory of the relation between psychic conflict and mental

disorder. The ego’s whole endeavour, Freud says, is ‘a reconciliation between its

various dependent relationships’. In the absence of such reconciliation, particular

disorders develop: the psychoses are the result of conflicts between the ego and

the world, depressive neuroses are the result of conflicts between the id and the

superego, and other neuroses are the result of conflicts between the ego and

the id.

While Freud’s general tripartite anatomy of the soul bears a close resemblance

to Plato’s, his particular treatment of the superego reminds the historian rather

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM347

three modern masters

348

more of Newman’s description of the conscience. Freud believed that the supergo

had its origin in the injunctions and prohibitions of the child’s parents, of which

it was the internalized residue.

The long period of childhood, during which the growing human being lives in

dependence on his parents, leaves behind it as a precipitate the formation in his ego

of a special agency in which this parental influence is prolonged. It has received the

name of superego.

Newman’s portrayal of conscience as echoing the reproaches of a mother and the

approval of a father seems more like a description of the formation of the super-

ego than a proof of the existence of a supernatural judge.

Freud would be indignant at figuring in a history of philosophy, since he

regarded himself above all as a scientist, dedicated to discovering the rigid deter-

minisms which underlay human illusions of freedom. In fact, most of his detailed

theories, when they have been made precise enough to admit of experimental test-

ing, have been proved to lack foundation. Among medical professionals, opinions

differ whether the techniques which took their rise from his practice of psycho-

analysis are, in any strict sense, effective forms of therapy. When they achieve

success, it is not by uncovering unalterable deterministic mechanisms, but by

expanding the freedom of choice of the individual. Despite the non-scientific

nature of his work, Freud’s influence on modern society has been pervasive: in

relation to sexual mores, to mental illness, to art and literature, and to interpersonal

relationships of many kinds.

The permissive attitude to sex of many societies in the late twentieth century

is undoubtedly due not only to the increased availability of efficient contracep-

tion, but also to the ideas of Freud. He was not the first thinker to assign the

sexual impulse a place of fundamental importance in the human psyche: so did

all those theologians who regarded the sin of Adam, which shaped our actual

human condition, as being sexual in origin, transmission, and effect. If, as

some people believe, nineteenth-century prudery succeeded in concealing the

importance of sex, the veil of concealment was even then easily torn away. As

Schopenhauer wrote, in a passage Freud loved to quote, it is the joke of life

that sex, the chief concern of man, should be pursued in secret. ‘In fact’, he said,

‘we see it every moment seat itself, as the true hereditary lord of the world, out

of the fullness of its own strength, upon the ancestral throne, and looking down

from there with scornful glances, laugh at the preparations which have been made

to bind it.’

Freud’s emphasis on infantile sexuality was one of the elements of his teaching

which contemporaries found most shocking. But the sentimental attitude to early

childhood which he attacked was one of comparatively recent origin. It was not,

for instance, shared by Augustine, who wrote in his Confessions:

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM348

three modern masters

349

What is innocent is not the infant’s mind, but the feebleness of his limbs. I have

myself watched and studied a jealous baby. He could not yet speak and, pale with

jealousy and bitterness, glared at his brother sharing his mother’s milk. Who is

unaware of this fact of experience?

What links Freud’s work with modern sexual permissiveness is not medical

research, but the persuasive character of his literary style. He did not assemble a

statistical demonstration of a connection between sexual abstinence and mental

illness; nor, in his published writings, did he recommend sexual licence. What he

did do was to give widespread currency to the metaphors which he shared with

Plato: the vision of sexual desire as a psychic fluid which seeks an outlet through

one channel or another. Seen in the light of that metaphor, sexual abstinence

appears as a dangerous damming up of forces which will eventually break through

restraining barriers with devasting effect on mental health.

The very concept of mental health, in its modern form, dates from the time

when Freud and his colleagues began to treat hysterical patients as genuine

invalids instead of malingerers. This, it has often been said, was as much a moral

decision as a medical discovery. But it was surely the right moral decision; and

hysteria was close enough to the paradigm of physical illness for the concept of

mental illness to have clear sense when applied to it. In ordinary illness the causes,

symptoms, and remedies of disease are all physical. In mental illness, whether or

not physical causes and remedies have been identified, the symptoms concern the

cognitive and affective life of the patient: disorders of perception, belief, and

emotion. In the diagnosis of whether perception is normal, of whether belief is

rational, of whether emotion is out of proportion, there is a gentle slope which

leads from clinical description to moral evaluation. This is strikingly seen in the

case of homosexual attraction, which was for long regarded as a psychopathologi-

cal disorder but has come to be regarded by many as a basis for the rational

choice of an alternative life-style. Forms of behaviour which before Freud would

have been regarded as transgressions worthy of punishment are now often judged,

in the courthouse no less than in the consulting room, as symptoms of maladies

fit for therapy. It is often said that Freud was not so much a medical man as a

moralist; that is true, but it is truer to say that he redrew the boundaries between

morals and medicine.

Perhaps Freud’s greatest influence has been on art and literature. This has a

certain irony, in the light of his unflattering view of artistic creation as something

very similar to neurosis: a sublimation of unsatisfied libido, translating into phantasy

form the unresolved conflicts of infantile sexuality. Since Freud’s theories became

well known, critics have delighted to interpret works of art in Oedipal terms, and

historians have turned with gusto to the writing of psychobiography, analysing

the actions of mature public figures on the basis of real or imagined features of

their childhood. Novelists have made use of associative techniques similar to

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM349

three modern masters

350

those of the analyst’s couch, and painters and sculptors have taken Freudian

symbols out of a dream world and given them concrete form. All of us, directly or

indirectly, have imbibed so much of Freud’s philosophy of mind that in discus-

sion of our relations with our family and friends we make unselfconscious use of

Freudian concepts. No other philosopher since Aristotle has made such a contri-

bution to the everyday vocabulary of morality.

AIBC20 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM350

logic and the foundations of mathematics

351

XXI

LOGIC AND THE

FOUNDATIONS OF

MATHEMATICS

Frege’s Logic

The most important event in the history of philosophy in the nineteenth century

was the invention of mathematical logic. This was not only a refoundation of the

science of logic itself, but had important consequences for the philosophy of

mathematics, the philosophy of language, and ultimately for philosophers’ under-

standing of the nature of philosophy itself.

The principal founder of mathematical logic was Gottlob Frege. Born on the

Baltic coast of Germany in 1848, Frege (1848–1925) took his doctorate in

philosophy at Göttingen, and taught at the University of Jena from 1874 until

his retirement in 1918. Apart from his intellectual activity his life was uneventful

and secluded; his work was little read in his lifetime, and even after his death

his influence was exercised originally through the writings of other philosophers.

But gradually he came to be recognized as the greatest of all philosophers of

mathematics, and as a philosopher of logic fit to be compared to Aristotle. His

invention of mathematical logic was one of the major contributions to the devel-

opments in many disciplines which resulted in the invention of computers. Thus

Frege affected the lives of all of us.

Frege’s productive career began in 1879 with the publication of a pamphlet

with the title Begriffschrift, or Concept Script. The concept script which gave the

book its title was a new symbolism designed to bring out with clarity logical rela-

tionships which were concealed in ordinary language. Frege’s own script, which

was logically elegant but typographically cumbersome, is no longer used in symbolic

logic; but the calculus which it formulated has ever since formed the basis of

modern logic.

Instead of the Aristotelian syllogistic, Frege placed at the front of logic the

propositional calculus first explored by the Stoics: that is to say, the branch of

logic that deals with those inferences which depend on the force of negation,

AIBC21 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM351

logic and the foundations of mathematics

352

conjunction, disjunction etc. when applied to sentences as wholes. Its funda-

mental principle – which again goes back to the Stoics – is to treat the truth-value

(i.e. the truth or falsehood) of sentences which contain connectives such as ‘and’,

‘if ’, ‘or’, as being determined solely by the truth-values of the component sen-

tences which are linked by the connectives – in the way in which the truth-value

of ‘John is fat and Mary is slim’ depends on the truth-values of ‘John is fat’ and

‘Mary is slim’. Composite sentences, in the logicians’ technical term, are treated

as truth-functions of the simple sentences of which they are put together. Frege’s

Begriffschrift contains the first systematic formulation of the propositional calculus;

it is presented in an axiomatic manner in which all laws of logic are derived, by

specified rules of inference, from a number of primitive principles.

Frege’s greatest contribution to logic was his invention of quantification theory:

that is to say, a method of symbolizing and rigorously displaying those inferences

that depend for their validity on expressions such as ‘all’ or ‘some’, ‘any’ or ‘every’,

‘no’ or ‘none’. This new method enabled him, among other things, to reformulate

traditional syllogistic.

There is an analogy between the inference

All men are mortal

Socrates is a man

So Socrates is mortal

and the inference

If Socrates is a man, then Socrates is mortal

Socrates is a man

So Socrates is mortal.

The second inference is a valid inference in the propositional calculus (if p then

q; but p, therefore q). But it cannot be regarded as a translation of the first, since

its first premiss seems to state something about Socrates in particular, whereas

if ‘All men are mortal’ is true, then

if x is a man, then x is mortal

will be true no matter whose name is substituted for the variable ‘x’. Indeed, it

will remain true even if we substitute the name of a non-man for x, since in that

case the antecedent will be false, and the whole sentence, in accordance with the

truth-functional rules for ‘if’-sentences, will turn out true. So we can express the

traditional proposition:

All men are mortal

in this way

For all x, if x is a man, x is mortal.

AIBC21 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM352

logic and the foundations of mathematics

353

This reformulation forms the basis of Frege’s quantification theory: to see how,

we have to explain how he conceived each of the items which go together to

make up the complex sentence.

Frege introduced into logic the terminology of algebra. An algebraic expres-

sion such as ‘x/2 + 1’ may be said to represent a function of x: the value of the

number represented by the whole expression will depend on what we substitute

for the variable ‘x’, or, in the technical term, what we take as the argument of the

function. Thus 3 will be the value of the function for the argument 4, and 4 will

be the value of the function for the argument 6. Frege applied the terminology of

argument, function, and value to expressions of ordinary language as well as to

expressions in mathematical notation. He replaced the grammatical notions of

subject and predicate with the mathematical notions of argument and function,

and he introduced truth-values as well as numbers as possible values for expres-

sions. Thus ‘x is a man’ represents a function which for the argument Socrates

takes the value true, and for the argument Venus takes the value false. The expres-

sion ‘for all x’, which introduces the sentence above, says, in Fregean terms, that

what follows (‘if x is a man, x is mortal’) is a function which is true for every

argument. Such an expression is called a quantifier.

Besides ‘for all x’, the universal quantifier, there is also the particular quantifier

‘for some x’ which says that what follows is true for at least one argument. Thus,

‘some swans are black’ can be represented in a Fregean dialect as ‘For some x, x

is a swan and x is black’. This sentence can be taken as equivalent to ‘there are

such things as black swans’; and indeed Frege made general use of the particular

quantifier in order to represent existence. Thus, ‘God exists’ or ‘there is a God’ is

represented in his system as ‘For some x, x is God’.

Using his novel notation for quantification, Frege was able to present a calculus

which formalized the theory of inference in a way more rigorous and more

general than the traditional Aristotelian syllogistic which up to the time of Kant

had been looked on as the be-all and end-all of logic. After Frege, for the first

time, formal logic could handle arguments which involved sentences with mul-

tiple quantification, sentences which are as it were quantified at both ends, such

as ‘Nobody knows everybody’ and ‘any schoolchild can master any language’.

Frege’s Logicism

In the Begriffschrift and its sequels Frege was not interested in logic for its own

sake. His motive in constructing the new concept script was to assist him in the

philosophy of mathematics. The question which above all he wanted to answer

was this: Do proofs in arithmetic rest on pure logic, being based solely upon

general laws operative in every sphere of knowledge, or do they need support

from empirical facts? The answer which he gave was that arithmetic itself could be

AIBC21 22/03/2006, 11:09 AM353