Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the utilitarians

314

for a crime which B has not committed; A’s motive is bad, but his intention may

be good if he genuinely believes B to be guilty. In itself, Bentham says, no motive

is either good or bad; words such as ‘lust’, ‘avarice’, and ‘cruelty’ denote bad

motives only in the sense that they are never properly applied except where the

motives they signify happen to be bad. ‘Lust’, for instance, is the name given to

sexual desire when the effects of it are regarded as bad. For Bentham motive does

not supply a separate ground for the moral qualification of an act: the only mental

state primarily relevant to the morality of a voluntary act is the agent’s belief

about its consequences. There is something of an irony in the fact that Bentham

should write so instructively about intention and motive when, in his own util-

itarian system, these have less moral importance than in any other system.

John Stuart Mill, in his book Utilitarianism, summed up the issue as follows.

‘He who saves a fellow-creature from drowning does what is morally right,

whether his motive be duty, or the hope of being paid for his trouble; he who

betrays the friend that trusts him is guilty of a crime, even if his object be to serve

another friend to whom he is under greater obligation.’ One motive may be

preferable to another on non-moral grounds; or because it may proceed from a

quality of character more likely to produce virtuous acts in the long term. But in

general ‘the motive has nothing to do with the morality of the action, though

much with the worth of the agent’.

The Utilitarianism of J. S. Mill

Mill softened down Bentham’s utilitarianism in several ways. Critics had objected

that to suppose that life has no higher end than pleasure was a doctrine worthy

only of swine. Mill responded by making a distinction between the quality of

pleasures. ‘Of two pleasures, if there be one to which all or almost all who have

experience of both give a decided preference, irrespective of any feeling of moral

obligation to prefer it, that is the more desirable pleasure.’ Armed with this dis-

tinction, he is able to conclude that ‘It is better to be a human being dissatisfied

than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’. In

applying the greatest happiness principle we must take account of this: the end for

which all other things are desirable is an existence exempt as far as possible from

pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments in point of both quantity and quality.

Bentham’s utilitarianism, with its denial of natural rights, would in principle

justify, in certain circumstances, highly autocratic government and great intrusions

upon individual liberty. Mill, in his writings, always strove to temper utilitarianism

with liberalism, and his brief On Liberty is an eloquent classic of liberal individualism.

The pamphlet seeks to set out the limits to the legitimate interference of

collective opinion with individual independence. He states his guiding principle

in the following terms.

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM314

the utilitarians

315

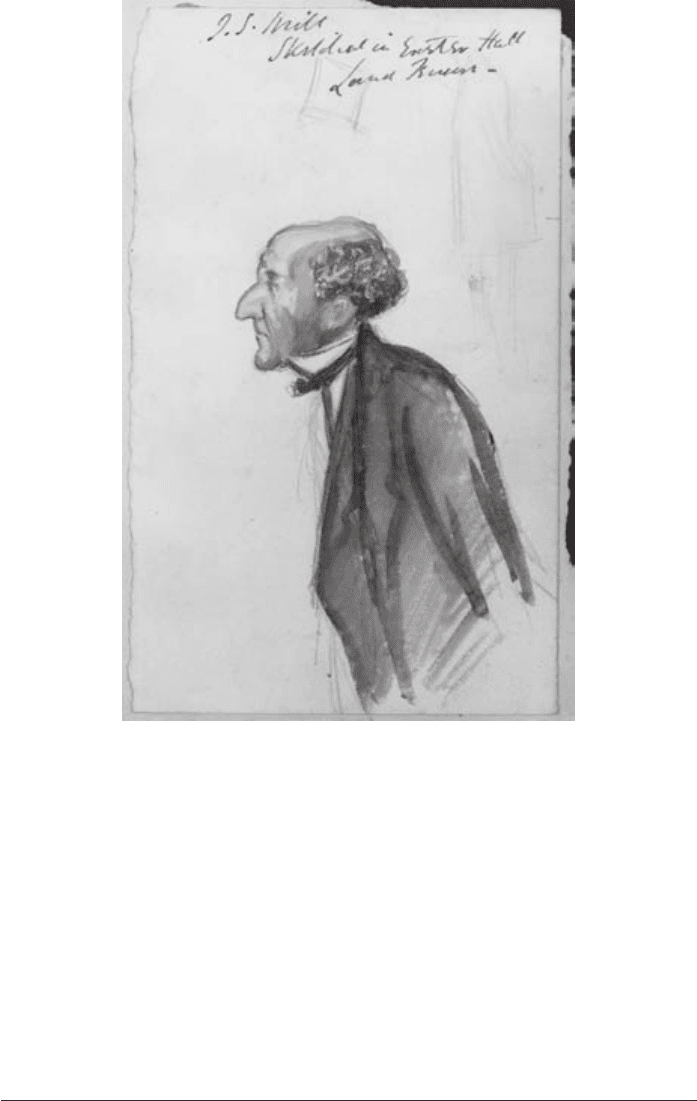

Figure 38 John Stuart Mill, by G. F. Watts.

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in inter-

fering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. The only

purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised

community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either

physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.

The only part of anyone’s conduct for which he is amenable to society is that

which concerns others. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual

is sovereign.

Mill applies his principle in particular in support of freedom of expression. If

an opinion is silenced, it may, for all we know, be true; if it is not true, it may

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM315

the utilitarians

316

contain a portion of truth; and even if it is wholly false, it is important that the

contrary opinion should be contested, otherwise it will be held either as a mere

prejudice, or as a formal profession devoid of conviction. On these grounds,

Mill affirms that freedom of opinion, and freedom of the expression of opinion,

is a ‘necessity to the mental well-being of mankind, on which all their other

well-being depends’.

Mill’s Logic

Apart from On Liberty Mill’s best known work is his essay on The Subjection of

Women, written in collaboration with his wife Harriet Taylor. But Mill’s reputa-

tion as a philosopher does not depend on his moral and political writings alone.

He was highly learned and very industrious; he began learning Greek at the age

of three, and published voluminous philosophical works while holding, for thirty-

five years, a full-time job with the East India Company. In theoretical philosophy

his most important work was A System of Logic, which he published in 1843 and

which went through eight editions in his lifetime.

Mill continued in the nineteenth century the traditions of the eighteenth-

century British Empiricists. He admired Berkeley, and tried to detach his theory

of matter from its theological context: our belief that physical objects persist in

existence when they are not perceived, he said, amounts to no more than our

continuing expectation of further perceptions of the objects. Matter is defined by

Mill as ‘a permanent possibility of sensation’; the external world is ‘the world of

possible sensations succeeding one another according to laws’.

In philosophy of mind, Mill agreed with Hume that ‘We have no conception of

Mind itself, as distinguished from its conscious manifestations’, but he was reluct-

ant to accept that his own mind was simply a series of feelings. He had an extra

difficulty about the existence of other minds. I can know the existence of minds

other than my own, he had to explain, by supposing that the behaviour of others

stands in a relation to sensations which is analogous to the relation in which my

behaviour stands to my own sensations. This claim is not easy to reconcile with

his general phenomenalist position, according to which other substances, includ-

ing other people, are merely permanent possibilities of my sensation.

Unlike previous empiricists, Mill had a serious interest in formal logic and in

the methodology of the sciences. His System of Logic (1843) begins with an

analysis of language, and in particular with a theory of naming.

Mill uses the word ‘name’ very broadly. Not only proper names like ‘Socrates’

but pronouns like ‘this’, definite descriptions like ‘the king who succeeded William

the Conqueror’, general terms like ‘man’ and ‘wise’, and abstract expressions like

‘old age’ are all counted as names in his system. Indeed, only words like ‘of’ and

‘or’ and ‘if ’ seem not to be names, in his system. According to Mill, all names

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM316

the utilitarians

317

denote things: proper names denote the things they are names of, and general

terms denote the things they are true of. Thus not only ‘Socrates’, but also ‘man’

and ‘wise’ denote Socrates.

For Mill, every proposition is a conjunction of names. This does not commit

him to the extreme nominalist view that every sentence is to be interpreted on

the model of one joining two proper names, as in ‘Tully is Cicero’. A sentence

joining two connotative names, like ‘all men are mortal’, tells us that certain

attributes (those, say, of rationality and animality) are always accompanied by the

attribute of mortality.

More important than what he has to say about names and propositions is Mill’s

theory of inference.

Inferences can be divided into real and verbal. The inference from ‘no great

general is a rash man’ to ‘no rash man is a great general’ is a verbal, not a real

inference; premise and conclusion say the same thing. There is real inference only

when we infer to a truth, in the conclusion, which is not contained in the

premises. There is, for instance, a real inference when we infer from particular

cases to a general conclusion, as in ‘Peter is mortal, James is mortal, John is

mortal, therefore all men are mortal’. But such inference is not deductive, but

inductive.

Is all deductive reasoning, then, merely verbal? Up to the time of Mill, the

syllogism was the paradigm of deductive reasoning. Is syllogistic reasoning real or

verbal inference? Suppose we argue from the premises ‘All men are mortal, and

Socrates is a man’ to the conclusion ‘Socrates is mortal’. It seems that if the

syllogism is deductively valid, then the conclusion must somehow have already

been counted in to the first premise: the mortality of Socrates must have been

part of the evidence which justifies us in asserting that all men are mortal. If, on

the other hand, the conclusion gives new information – if, for instance, we sub-

stitute for ‘Socrates’ the name of someone not yet dead (Mill used the example

‘The Duke of Wellington’) – then we find that it is not really being derived from

the first premise. The major premise, Mill says, is merely a formula for drawing

inferences, and all real inference is from particulars to particulars.

Inference beginning from particular cases had been named by logicians ‘induc-

tion’. In some cases, induction appears to provide a general conclusion: from

‘Peter is a Jew, James is a Jew, John is a Jew . . .’, I can, having enumerated all

the Apostles, conclude ‘All the Apostles are Jews’. But this procedure, which is

sometimes called ‘perfect induction’, does not, according to Mill, really take us

from particular to general: the conclusion is merely an abridged notation for the

particular facts enunciated in the premises. Some logicians had maintained that

there was another sort of induction, imperfect induction (Mill calls it ‘induction

by simple enumeration’), which led from particular cases to general laws. But

the purported general laws are merely formulae for making inferences. Genuine

inductive inference takes us from known particulars to unknown particulars.

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM317

the utilitarians

318

If induction cannot be brought within the framework of the syllogism, this

does not mean that it operates without any rules of its own. Mill sets out five

rules, or canons, of experimental inquiry to guide the inductive discovery of

causes and effects. We may consider, as illustrations, the first two, which Mill calls

respectively the method of agreement and disagreement.

The first states that if a phenomenon F appears in the conjunction of the

circumstances A, B, and C, and also in the conjunction of the circumstances C,

D, and E, then we are to conclude that C, the only common feature, is causally

related to F. The second states that if F occurs in the presence of A, B, and C, but

not in the presence of A, B, and D, then we are to conclude that C, the only

feature differentiating the two cases, is causally related to F. Mill gives as an

illustration of this second canon: ‘When a man is shot through the heart, it is by

this method we know that it was the gunshot which killed him: for he was in the

fulness of life immediately before, all circumstances being the same, except the

wound.’

Like all inductive procedures, Mill’s methods seem to assume the constancy of

general laws. As Mill explicitly says, ‘The proposition that the course of Nature is

uniform, is the fundamental principle, or general axiom, of Induction.’ But what

is the status of this principle? Mill sometimes seems to treat it as if it was an

empirical generalization. He says, for instance, that it would be rash to assume

that the law of causation applies on distant stars. But if this very general principle

is the basis of induction, surely it cannot itself be established by induction.

It is not only the law of causation which presents difficulties for Mill’s system.

So too do the truths of mathematics. Mill did not think – as some other empiri-

cists have done – that mathematical propositions were merely verbal propositions

which spelt out the consequences of definitions. The fundamental axioms of

arithmetic, and Euclid’s axioms of geometry, he maintains, state matters of fact.

Accordingly, he had in consistency to conclude that arithmetic and geometry, no

less than physics, consist of empirical hypotheses. The hypotheses of mathematics

are of very great generality, and have been most handsomely confirmed in our

experience; none the less, they remain hypotheses, corrigible in the light of later

experience.

Mill’s assertion that mathematical truths were empirical generalizations was

inspired by his overriding aim in The System of Logic, which was to refute the

notion which he regarded as ‘the great intellectual support of false doctrines and

bad institutions’, namely, the thesis that truths external to the mind may be

known by intuition independent of experience. His view of mathematics was very

soon to be shown as untenable by the German philosopher Gottlob Frege, and

after Frege’s work even those who had great sympathy with Mill’s empiricism –

including his godson Bertrand Russell – abandoned his philosophy of arithmetic.

After MillUs death at Avignon in 1873 an engaging Autobiography was pub-

lished posthumously, and some essays on religious topics. In his essay Theism,

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM318

the utilitarians

319

having reflected on the problem set by the presence of evil and good in the

world, Mill came to the conclusion that it could only be solved by acknowledging

the existence of God while denying divine omnipotence. He concluded thus:

These, then, are the net results of natural theology on the question of the divine

attributes. A being of great but limited power, how or by what limited we cannot

even conjecture; of great and perhaps unlimited intelligence, but perhaps also more

narrowly limited power than this, who desires and pays some regard to the happiness

of his creatures, but who seems to have other motives of action which he cares more

for, and who can hardly be supposed to have created the universe for that purpose

alone. Such is the deity whom natural religion points to, and any idea of God more

captivating than this comes only from human wishes, or from the teaching of either

real or imaginary revelation.

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM319

three nineteenth-century philosophers

320

XIX

THREE NINETEENTH-

CENTURY PHILOSOPHERS

Schopenhauer

The most interesting German philosopher of the nineteenth century was Arthur

Schopenhauer, who was born in Danzig in 1788 and studied philosophy at

Göttingen in 1810 after a false start as a medical student. He admired Kant but

not Kant’s successors. He attended the lectures of Fichte in Berlin in 1811, but

was disgusted by both his obscurity and his nationalism. In the writings of Hegel

and his disciples he complained of ‘the narcotic effect of long-spun periods

without a single idea in them’. His own style, first exhibited in his doctoral

dissertation of 1813, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason,

was energetic and luminous, and won the praise of the great poet Goethe. In

Dresden between 1814 and 1818 Schopenhauer composed his philosophical

masterpiece, The World as Will and Idea, which he republished in an expanded

form in 1844. In 1820 he went to Berlin and offered a series of lectures, but the

students, injudiciously, preferred to hear Hegel who was lecturing at the same

hour. The boycott of his lectures fuelled his distaste for the Hegelian system,

which he regarded as mostly nonsense. In 1839 he won his first public recogni-

tion with a Norwegian prize for an Essay on the Freedom of the Will. Schopenhauer

was a brilliant essayist, and when his essays were published in 1851 under the title

Parerga and Paralipomena he emerged from years of obscurity and neglect to

become a famous philosopher. He died in 1860.

Schopenhauer’s major work, The World as Will and Idea, contains four books,

the first and third devoted to the World as Idea, and the second and fourth to the

World as Will. His philosophy of the World as Idea is closely based on Kant, but

he writes so much more lucidly and wittily than Kant that the effect is rather as if

a work of Henry James had been rewritten by Evelyn Waugh.

Book One begins with the statement ‘The world is my idea’. By ‘idea’ (Vorstellung)

Schopenhauer does not mean a concept, but a concrete, intuitive, experience. If

a man is to achieve philosophical wisdom, he must accept that ‘what he knows is

not a sun and an earth, but only an eye that sees a sun, a hand that feels an earth’.

AIBC19 22/03/2006, 11:08 AM320

three nineteenth-century philosophers

321

Figure 39 A cartoon by Wilhelm Busch of Schopenhauer with his poodle.

(Schopenhauer Archiv, Stadt- und Universitatsbibliotek, Frankfurt-am-Main; photo: akg-images)

The world exists only as idea, that is to say, exists only in relation to conscious-

ness. This truth, he says, was first realized in Indian philosophy, with its doctrine

of Maya or appearance, but it was rediscovered in Europe by Berkeley.

For each of us, our own body is the starting point of our perception of the

world; other objects are known through their effects on each other, by means of

the principle of causality, which is grasped by the understanding. Understanding

is common to men and animals, because animals too perceive objects in space and

time and so they too must be applying the law of causality; indeed animal sagacity

sometimes surpasses human understanding. Human language-users, however, have

not only understanding but reason, that is to say abstract knowledge embodied in

AIBC19 22/03/2006, 11:08 AM321

three nineteenth-century philosophers

322

concepts; because of this man far surpasses other animals in power and also in

suffering. They live in the present alone, man lives also in the future and the past.

The three great gifts which reason gives to humans are speech, deliberation in

action, and science. The importance of rational or abstract knowledge is that it can

be shared and retained. For practical purposes, mere understanding may be pre-

ferable: ‘it is of no use to me to know in the abstract the exact angle, in degrees

and minutes, at which I must apply a razor, if I do not know it intuitively, that is,

if I have not got the feel of it.’ But when the help of others is required, or long-

term planning is necessary, abstract knowledge is essential. And conduct can only

be ethical if based on principles; but principles are abstract.

All this is not very different from Kant. Schopenhauer criticizes Kant only for

being half-hearted in accepting that the world is only an object in relation to a

subject, and for insisting on the existence of a thing-in-itself behind the veil of

appearance. It is in his presentation, in the second book, of the world as will, that

Schopenhauer shows his originality.

He starts from considering the nature of sciences such as mechanics and physics.

These explain the motions of bodies in terms of laws such as those of inertia

and gravitation. But these laws speak of forces whose inner nature they leave

completely unexplained. ‘The force on account of which a stone falls to the ground

or one body repels another is, in its inner nature, not less strange and mysterious

than that which produces the movements and the growth of an animal.’ Scientists

and philosophers can never arrive at the real nature of things from without: they

are like people who go around a castle looking in vain for an entrance, and con-

tenting themselves with sketching its façade.

None of us would, indeed, ever be able to penetrate the meaning of the world

if we were mere knowing subjects (‘winged cherubs without a body’). But I am

myself rooted in the world; my knowledge of it is given me through my body,

which is not just one object among others, but has an active power of which I am

directly conscious. It is indeed this special relationship to one body which makes

me the individual I am.

The answer to the riddle is given to the subject of knowledge, who appears as an

individual, and the answer is will. This and this alone gives him the key to his own

existence, reveals to him the significance, shows him the inner mechanism of his

being, of his action, of his movements.

Acts of the will are identical with movements of the body; the will and the move-

ment are not two different events linked by causality. The action of the body is an

act of the will made perceptible, and indeed the whole body, Schopenhauer says,

is nothing but objectified will, will become visible, will become idea. The body

and all its parts are the visible expression of the will and its several desires: thus,

‘teeth, throat and bowels are objectified hunger; the organs of generation are

AIBC19 22/03/2006, 11:08 AM322

three nineteenth-century philosophers

323

objectified sexual desire; the grasping hand, the hurrying feet, correspond to the

more indirect desires of the will which they express’.

Each of us knows himself both as an object and as a will; and this is the key to

the nature of every phenomenon in nature. The inner nature of all objects must

be the same as that which in ourselves we call will. What else could it be? Besides

will and idea nothing is known to us. The word ‘will’, Schopenhauer says, is like

a magic spell which discloses to us the inmost being of everything in nature.

There are many different grades of will, and only the higher grades are accom-

panied by knowledge and self-determination.

If, therefore, I say, the force which attracts a stone to the earth is according to its

nature, in itself and apart from all idea, will, I shall not be supposed to express in this

opinion the insane opinion that the stone moves itself in accordance with a known

motive, merely because this is the way in which will appears in man.

Will is the force which lives in the plant, the force by which crystal is formed and

by which the magnet turns to the North Pole. Here at last we find what Kant

looked for in vain: all ideas are phenomenal existence, the will alone is a thing

in itself.

Schopenhauer’s will, which is active even in inanimate objects, appears to be

the same as Aristotle’s natural appetite, restated in terms of Newton’s laws instead

of in terms of the theory of the natural place of the elements. Why does he call it

‘will’, then, rather than ‘appetite’ or simply ‘force’? If we explain force in terms

of will, Schopenhauer replies, we explain the less known by the better known;

if, instead, we regard the will as merely a species of force, we renounce the only

immediate knowledge we have of the inner nature of the world.

But there is, Schopenhauer agrees, a great difference between the higher and

lower grades of will. In the higher grades individuality occupies a prominent

position: each human has a strong individual personality, and so to a lesser extent

do the higher species of brute animals. ‘The farther down we go, the more

completely is every trace of the individual character lost in the common character

of the species.’ In the inorganic kingdom of nature all individuality disappears.

Nature should be seen as a field of conflict between different grades of will.

A magnet lifting a piece of iron is a victory of a higher form of will (electricity)

over a lower (gravitation). A human being in health is a triumph of the Idea of

the self-conscious organism over the physical and chemical laws which originally

governed the humours of the body, and against which it is engaged in constant

battle.

Hence also in general the burden of physical life, the necessity of sleep, and, finally,

of death; for at last these subdued forces of nature, assisted by circumstances, win

back from the organism, wearied even by the constant victory, the matter it took

from them, and attain to an unimpeded expression of their being.

AIBC19 22/03/2006, 11:08 AM323