Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

german idealism and materialism

304

the Absolute face to face with itself. Reader, I hope you realize what is happening

as you are reading!

If we take Hegel seriously, however, we should stop the book at this point. For

Hegel thought that with his own system, the history of philosophy comes to an

end. In his Lectures on the History of Philosophy he displays earlier philosophies as

succumbing, one by one, to a dialectical advance marching steadily in the direc-

tion of German Idealism. A new epoch has now arisen, he tells us, in which finite

self-consciousness has ceased to be finite, and absolute self-consciousness has

achieved reality. The sole task of the history of philosophy is to narrate the strife

between finite and infinite self-consciousness; now that the battle is over, it has

reached its goal.

Marx and the Young Hegelians

Hegel’s importance in the history of philosophy derives not so much from the

content of his writing as from the enormous influence he exercised on thinkers

who followed him. Of all those whom he influenced, the one who in his turn was

most influential was Karl Marx, who described his own philosophical vocation as

‘turning Hegel upside-down’.

Marx was born in Trier, in 1818, to a liberal Protestant family of Jewish

descent. He attended university first at Bonn and then at Berlin, where he studied

the philosophy of Hegel under Bruno Bauer, the leader of a left-wing group

known as the Young Hegelians. From Hegel and Bauer Marx learned to view

history as a dialectical process. That is to say, history came in a succession of

stages which followed one another, like the steps in a geometrical proof, in an

order determined by fundamental logical or metaphysical principles. This was a

vision which he retained throughout his life.

The Young Hegelians attached great importance to Hegel’s concept of alien-

ation, that is to say, treating as alien something with which by rights one should

identify. Alienation is the state in which people view as exterior to themselves

something which is truly an intrinsic element of their own being. What Hegel

himself had in mind was that individuals, all of whom were manifestations of a

single Spirit, saw each other as hostile rivals rather than as elements of a single

unity. The Young Hegelians rejected the idea of the universal spirit, but retained

the notion of alienation, locating it elsewhere in the system.

Hegel had seen his philosophy as a sophisticated and self-conscious presenta-

tion of truths which had been given uncritical and mythical expression in religious

doctrines. For the Young Hegelians, religion was not to be translated, but elimin-

ated. For Bauer, and still more for Ludwig Feuerbach, religion was the supreme

form of alienation. Humans, who were the highest form of beings, projected their

own life and consciousness into an unreal heaven. The essence of man is the unity

AIBC17 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM304

german idealism and materialism

305

of reason, will, and love; unwilling to accept limits to these perfections, we form

the idea of a God of infinite knowledge, infinite will, and infinite love, and man

venerates Him as an independent Being distinct from man himself. ‘Religion is

the separation of man from himself: he sets God over against himself as an

opposed being.’

Marx was in sympathy with the Young Hegelian critique of religion, which

he was later to describe as ‘the opium of the people’, but from an early stage he

placed the focus of alienation elsewhere. He wrote:

Money is the universal, self-constituted value of all things. Hence it has robbed the

whole world, the human world as well as nature, of its proper value. Money is the

alienated essence of man’s labour and life, and this alien essence dominates him as

he worships it.

In 1841 he wrote a critique of Hegel’s philosophy of the State, in which he attacked

the theory that private property was the basis of civil society. In so far as a State

is based on private property it is itself an alienation of man’s true nature.

In 1842 Marx became the editor of a liberal journal, the Rheinische Zeitung.

The Prussian government regarded it as subversive, and closed it down. Marx,

out of a job, and newly married, migrated to Paris with his wife, Jenny. There he

found further work as a journalist, and made a number of radical friends includ-

ing the revolutionary socialist Friedrich Engels who became his right-hand-man.

He also made a study of the writings of British economists such as Adam Smith,

and began work on his own economic theory. His basic insight was that since

money is a form of alienation, all purely economic relationships – such as that

between worker and employer – are alienated forms of social intercourse, and

indeed a form of slavery which debases both slave and master. Only the abolition

of wage slavery and the replacement of private property by communism can put

an end to human alienation.

Soon he was forced to migrate again, this time to Brussels. There, with Engels,

Marx wrote The German Ideology, a work of philosophical criticism which was not

published until long after his death. In it he enunciates the principle that ‘life

determines consciousness, not consciousness life’. History is determined, not by

the mental history of a Hegelian Spirit, nor by the thoughts and theories of

human individuals, but by the processes of production of the necessities of life.

Marx had earlier reached the conclusion that human alienation would not be

ended by philosophical criticism alone. It was not simply that, as he famously put

it, ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it’.

The change that was necessary would have to be a violent one, and that called for

an alliance between the philosophers and the workers. ‘As philosophy finds its

material weapons in the proletariat, the proletariat finds its intellectual weapons in

philosophy.’ In 1847 a newly-formed Communist League met in London, and

AIBC17 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM305

german idealism and materialism

306

Marx and Engels were commissioned to write its manifesto, which was published

early in 1848, just before a series of revolutions rocked the major kingdoms of

the European continent.

‘The history of all hitherto existing society,’ states the Manifesto, ‘is the history

of class struggles.’ This is a consequence of the materialist theory of history.

Superficially, history may appear to be a record of conflicts between different

nations and different religions; but the underlying realities throughout the ages

are the forces of material production and the classes which are created by the

relationships between those involved in that production. The legal, political, and

religious institutions which loom so large in historical narrative are only a super-

structure concealing the fundamental levels of history: the forces and powers of

production, and the economic relations among the producers. The philosophy,

or ‘ideology’, which is used to justify the legal and political institutions of each

epoch are merely a smokescreen concealing the vested interests of the ruling

classes of the time.

Capitalism and its Discontents

Marx developed these ideas in many later writings, culminating in his great

Capital, written in London in the final period of his life, when he had been

forced to leave France in the aftermath of the revolution of 1848. In that work he

explained in detail how the course of history was dictated by the forces and

relations of production.

Productive forces, in Marx’s terms, include the raw materials, machinery, and

labour, which go to make a finished product: as wheat, a mill, and a mill-worker

are all needed to produce flour. The relations of production are economic rela-

tions which involve these forces, such as the ownership of the mill and the hiring

of the worker. Developments in technology lead to different relations of produc-

tion: in the age of the hand-mill, the worker is the serf of the feudal lord; in the

age of the steam-mill he is the employee of the capitalist. Changes in technology

can render existing relations of production obsolete: a steam-mill demands mobile

workers, not serfs tied to the land. When the relations of production no longer

match the productive forces, Marx believed, these relations ‘turn into fetters’ and

a social revolution takes place.

Marx divided the past, present, and future history of the relations of production

into six phases: primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism,

and ultimate communism. He believed that the capitalist society in which he lived

was in a state of crisis, and would shortly pass through a revolutionary change

which would usher in the final stages first of socialism and then of communism.

The crisis which capitalism had reached, he believed, was not a contingent his-

torical fact; it was something inherent in the nature of capitalism itself. He based

AIBC17 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM306

german idealism and materialism

307

this conclusion on two economic theories: the labour theory of value, and the

theory of surplus value.

Following a suggestion which goes back ultimately to Aristotle, Marx believed

that the true value of any product was in proportion to the amount of labour put

into it. That thesis enables us to decide what a product is worth only if we have

a way of measuring the value of labour. The way to do that is to work out the

cost of keeping the labourer alive and well for the time it takes to do the job.

Hence, if it takes a labourer a day to produce a quantity of flour, that flour is

worth the cost of one day’s subsistence.

Under capitalism, however, prices in the market are determined not by true

value, but by supply and demand. The capitalist, who owns the raw material and

the means of production, having paid the worker a wage equal to his day’s

subsistence, say £1, can often sell the product for many times that sum, say £10.

The difference between the subsistence wage and the market price is the surplus

value, in this case £9. Under capitalism, no part of this surplus value is returned

to the worker, it is all pocketed by the employer. The effect is that only one-tenth

of the labourer’s work is for his own benefit; nine-tenths of it is just to produce

profit for the capitalist (see Plate 15).

As technology develops, and the labourer’s productivity increases accordingly,

surplus value increases and the proportion of his work which is returned to him

becomes smaller and smaller. Finally this exploitation is bound to reach a point at

which the proletariat finds it intolerable, and rises in revolt. The capitalist system

will be replaced by the dictatorship of the proletariat, which will abolish private

property and introduce a socialist state in which the means of production are

totally under central government control. But the socialist state will itself be only

temporary, and it will wither away to be replaced by a communist society in

which the interests of the individual and the community will be identical.

The theory of surplus value suffers from a fatal weakness. Marx offers no

convincing reason why the capitalist, no matter how great his profits, should pay

no more than a subsistence wage. But this thesis is an essential element in his

prediction that capitalism would inevitably lead to revolution, and do so soonest

in those states where technology, and therefore exploitation, was progressing

fastest. In fact, employers soon began, and have since continued, to pay wages

well above subsistence level in advanced industrialized countries. It was not in

them but in backward Russia that the first proletarian revolution occurred.

If we treat Marxism as a scientific hypothesis, to be judged by the success of its

predictions, it must be said that it has been totally discredited by the course of

history since Marx’s death. But whatever Marx himself may have thought, his

theories are essentially philosophical rather than scientific; and judged from that

standpoint, they can claim both successes and failures. On the one hand, though

few historians nowadays accept that events are determined totally by economic

factors, no historian, not even a historian of philosophy, would dare to deny the

AIBC17 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM307

german idealism and materialism

308

influence of those factors on politics and culture. On the other hand, even in

countries which underwent socialist revolutions of a Marxist type the power

wielded by individuals, such as Lenin, Stalin and Mao, has given the lie to the

theory that only impersonal forces determine the course of history. Finally, the

thesis that ideology is merely the smokescreen of the status quo is refuted by

the enormous influence which has been exerted, for good or ill, by Marx’s

own system of ideas, considered not as a scientific theory but as an inspiration

to political activism. If life determines consciousness, consciousness also deter-

mines life.

AIBC17 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM308

the utilitarians

309

XVIII

THE UTILITARIANS

Jeremy Bentham

Britain survived the Napoleonic era without invasion and without revolution.

Government remained in the hands of a privileged group, and in times of na-

tional crisis under Prime Ministers such as the younger Pitt and Lord Liverpool,

who were highly autocratic; there was a long way yet to go before the country

became a modern democracy. Reform was achieved, but in slow and constitu-

tional stages, rather than by violent upheaval or dramatic coup d’état.

One of those who did most to make British public opinion aware of the need

for reform was Jeremy Bentham, an Oxford-educated lawyer who in the year

of the French Revolution, at the age of forty-one, published an Introduction to

the Principles of Morals and Legislation. He had already, in 1776, published an

anonymous attack on the English legal system as recently presented in Sir William

Blackstone’s commentaries. He was much interested in penal reform, and on

a visit to Russia he had conceived the idea of a model prison, the Panopticon.

William Pitt’s government passed an Act of Parliament authorizing the scheme,

but it was defeated by ducal landowners who did not want a prison near their

London estates. In 1808 he became friends with James Mill and shared in the

education of his young son John Stuart. He wrote many papers on legal and

constitutional matters, most of which remained unpublished in his lifetime, and

spent years on the preparation of a constitutional code, which was unfinished

when he died. In 1817 he published a plan for parliamentary reform, followed

by a draft Radical Reform Bill. He died in 1832 a few weeks after the Great

Reform Bill had been passed, widely extending the parliamentary franchise. His

body is preserved in the library of University College, London, which he helped

to found.

Bentham’s Principles is the founding document of the school of moral and

political thought known as Utilitarianism, developed after him by John Stuart

Mill, and continuing to flourish up to the present day. The guiding idea of the

system is what Bentham calls ‘the principle of utility’, or ‘the greatest happiness

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM309

the utilitarians

310

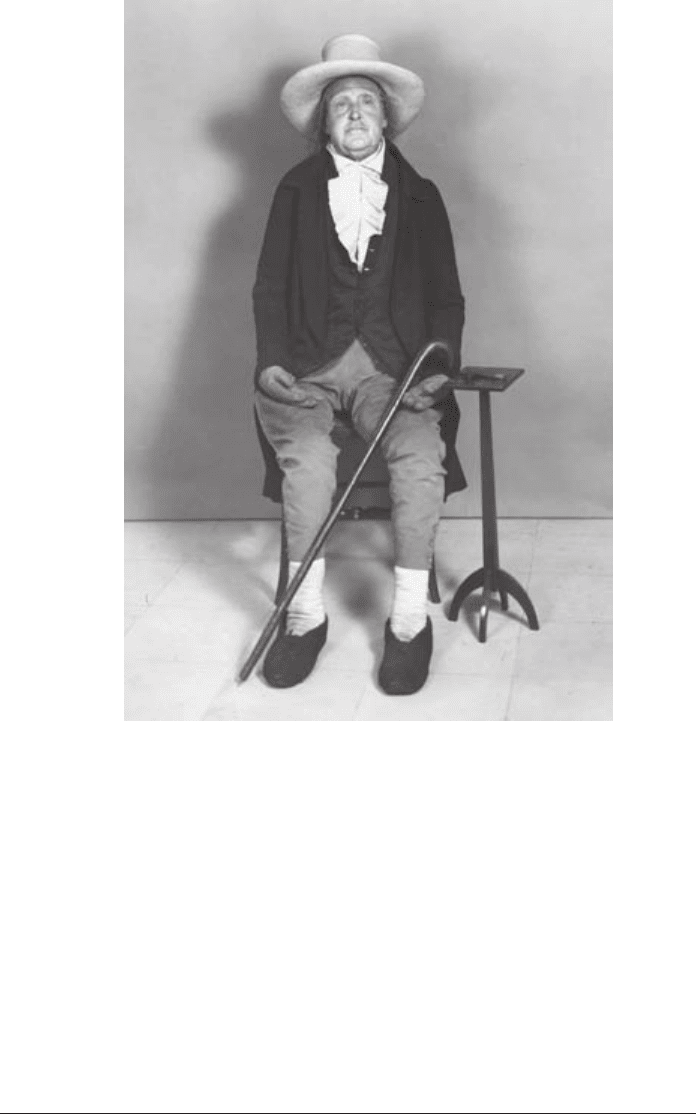

Figure 37 Jeremy Bentham’s ‘auto-icon’ (i.e. his remains preserved in a waxwork).

(University College London)

principle’. The principle of utility evaluates every action according to the tend-

ency which it appears to have to augment or diminish happiness. The promotion

of the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the only right and proper end

of human action, and laws and legal systems are to be tested by their conformity,

or lack of conformity, with this aim. The principle of utility enables us to distin-

guish good laws from bad, and it is the only source of political obligation. Belief

in natural law, or natural rights, or social contracts, Bentham maintained, is

nothing more than superstition.

‘The greatest happiness of the greatest number’ is one of those philosophical

slogans, like ‘the best of all possible worlds’ or ‘that than which nothing greater

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM310

the utilitarians

311

can be conceived’, which are impressive on first hearing, but which when probed

turn out to to have no clear meaning. It is not at all clear how we can measure

happiness and compare the quantity of happiness in different people, even if we

understand happiness in Bentham’s rather crude way as being pleasant sensation.

Again Bentham provides no consistent answer to the question ‘Greatest number

of what?’ Should we add ‘voters’ or ‘citizens’ or ‘human beings’ or ‘sentient

beings’? Again, should moralists and politicians attempt to control the number of

candidates for happiness, by taking steps to increase or diminish the population?

If so, in which direction? Most difficult of all, how do we balance the quantity

of happiness with the quantity of people? Suppose we have devised a scale from 0

to 100, on which 100 represents supreme happiness, and 0 represents supreme

misery. Should we prefer a state in which 51 per cent of the people score 51, and

49 per cent score 49, to a state in which 80 per cent of the people score 100 and

20 per cent score 0? If we try, in a simple way, to operate what Bentham calls ‘the

felicific calculus’, state A seems to score only 5002 points, and state B to score

8000 points. But anyone with a care for equality, or distributive justice, might

hesitate before casting a vote for state B.

Bentham was well aware of the difficulties in putting his slogan into practice,

and offers, for instance, recipes for the measurement of pleasures: they are to

be valued in accordance with their intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity,

fecundity, purity, and extension. He even offers a mnemonic rhyme to aid in

operating the calculus:

Intense, long, certain, speedy, fruitful, pure –

Such marks in pleasures and in pains endure.

Such pleasures seek if private be thy end;

If it be public, wide let them extend.

Such pains avoid, whichever be thy view

If pains must come, let them extend to few.

Later Utilitarians have devoted great ingenuity to dealing with the kinds of

problem outlined in the previous paragraph. But it remains true to this day that

the greatest happiness principle remains the title of a research programme rather

than an actual recipe for moral or political action.

Bentham’s influence on moral philosophy has been enormous. We may divide

moral philosophers into absolutists and consequentialists. Absolutists believe that

there are some kinds of actions which are intrinsically wrong and should never

be done no matter what the consequences are of refraining from doing them.

Consequentialists believe that the morality of actions should be judged by their

consequences, and that there is no category of act which may not, in special cir-

cumstances, be justified by its consequences. Prior to Bentham most philosophers

were absolutists, because they believed in a natural law or in natural rights. If

there are natural rights and a natural law, then some kinds of action, actions

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM311

the utilitarians

312

which violate those rights or conflict with that law, are wrong, no matter what

their consequences. Bentham’s attack on the notions of natural law and natural

rights has been more influential than his advocacy of the principle of utility: it has

had the effect of making consequentialism respectable in moral philosophy.

Consequentialists, like Bentham, judge actions by their consequences, and there

is no class of actions which is ruled out in advance. A believer in natural law, told

that some Herod or Nero has killed five thousand citizens guilty of no crime,

can say straightway ‘that was a wicked act’. The consequentialist, before making

such a judgement, must say ‘tell me more’. What were the consequences of the

massacre? What would have happened if the ruler had allowed the five thousand

to live?

The consequentialism which can trace its origin to Bentham is nowadays wide-

spread among professional philosophers. Thoroughgoing consequentialism is prob-

ably more popular in theory than in practice: outside philosophy seminars most

people probably believe that some actions are so outrageous that they should

morally be ruled out in advance, and reject the idea that one should literally stop

at nothing in the pursuit of desirable consequences. But in present-day discus-

sions of, for instance, topics in medical ethics, it is consequentialists who have the

greater say in the formation of policy, at least in English-speaking countries. This

is because they talk in the cost–benefit terms which technologists and policy-

makers instinctively understand. And among the general non-professional public,

many people share Bentham’s suspicion of the idea that some classes of action are

absolutely prohibited.

Where, people ask, do these absolute prohibitions come from? No doubt

religious believers see them as coming from God; but how can they convince

unbelievers of this? Can there be a prohibition without a prohibiter? Do not

those who subscribe to absolute prohibitions merely express the prejudices of

their upbringing?

The answer is to be found in the nature of morality itself. There are three

elements which are essential to morality: a moral community, a set of moral

values, and a moral code. All three are necessary. First, it is as impossible to have

a purely private morality as it is to have a purely private language, and for very

similar reasons. Secondly, the moral life of the community consists in the shared

pursuit of non-material values such as fairness, truth, comradeship, freedom: it is

this which distinguishes between morality and economics. Thirdly, this pursuit is

carried out within a framework which excludes certain prohibited types of beha-

viour: it is this which marks the distinction between morality and aesthetics. The

answer to the question ‘Who does the prohibiting?’ is that it is the members of

the moral community: membership of a common moral society involves subscrip-

tion to a common code. In attacking the notion that some things are absolutely

wrong, Bentham was attacking not just one form of morality, but something

constitutive of morality as such.

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM312

the utilitarians

313

Despite the baneful ethical system he originated, Bentham’s detailed discussions

of particular issues are often excellent. He writes briskly, and economically, mak-

ing acute and relevant distinctions, and packing a great weight of argument into

lucid and business-like paragraphs. Consider, as an instance, this discussion of the

purpose of the penal system:

The immediate principal end of punishment is to control action. This action is either

that of the offender, or of others: that of the offender it controls by its influence,

either on his will, in which case it is said to operate in the way of reformation; or on

his physical power, in which case it is said to operate by disablement; that of others

it can influence no otherwise than by its influence over their wills; in which case it is

said to operate in the way of example.

Bentham rejected the retributive theory of punishment, according to which just-

ice demands that he who has done harm shall suffer harm, whether or not his

suffering has any deterrent or remedial effect on himself or others. Such retribu-

tion, plain rendering of evil for evil, would simply increase the amount of evil in

the world rather than restoring any balance of justice. Since punishment involves

the infliction of pain, it can only be justified if it promises to exclude some greater

evil. The principal purpose of punishment, he believed, was deterrence; and

punishment should not be inflicted in cases where it would have no deterrent

effect, either on the offender or on others, nor should it be inflicted to any greater

extent than is necessary to deter. Bentham drew up a set of rules setting out the

proportion between punishments and offences, based not on the retributive prin-

ciple of ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’ but on the effect which the prospect

of punishment will have on the calculation by a potential offender of the profit and

loss likely to follow on the offence. Any remedial effect of punishment, Bentham

believed, was always bound to be subsidiary to the deterrent effect, and in practice,

in the conditions of most actual prisons, was unlikely to be achieved.

Bentham also made valuable contributions in more general areas of moral

philosophy. For instance, he expounded the concept of intention more lucidly

than any previous writer. An act, he said, might be intentional without its con-

sequences being so: ‘thus, you may intend to touch a man without intending to

hurt him: and yet, as the consequences turn out, you may chance to hurt him’. A

consequence might be either directly intentional (‘when the prospect of produc-

ing it constituted one of the links in the chain of causes by which the person was

determined to act’) or obliquely intentional (when the consequence was foreseen

as likely, but the prospect of producing it formed no link in the determining

chain). Among directly intentional consequences he distinguishes between those

which are ultimately or immediately intentional; this corresponds to the traditional

distinction between ends and means.

Bentham distinguishes between intention and motive: a man’s intentions may

be good and his motives bad. A, for instance, may prosecute B, out of malice,

AIBC18 22/03/2006, 11:07 AM313