Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

british philosophy in the eighteenth century

264

we may be apt to think the whole to be only a dream of fanciful men, who have

entangled themselves in cobwebs spun out of their own brain.

In fact, the recent history of philosophy shows how even the most intelligent

people can go wrong if they start from false first principles.

The initial problem with the theory of ideas is the ambiguity of the word ‘idea’.

In ordinary language, Reid maintains, it means an act of mind: to have an idea of

anything is to conceive it. But philosophers have given it a different meaning,

whereby it does not signify the act of conceiving, but some object of thought.

These ideas are first introduced into philosophy ‘in the humble character of

images or representatives of things’ but by degrees they have ‘supplanted their

constituents and undermined everything but themselves’.

In fact, Reid maintains, ideas in the philosophical sense are mere fictions. We

do indeed have conceptions of many things; but a conception is not an image,

and the postulation of ideas which are images is neither necessary nor sufficient to

explain how we acquire and use these concepts. Not only do philosophers like

Locke confuse concepts with images, but they start from the wrong end when

they consider concepts themselves. They talk as if knowledge begins with bare

conception, separate from belief, and that belief arises from the comparison of

simple ideas. The truth is the reverse: we begin with natural and original judge-

ments, and we later analyse them into indvidual concepts. Seeing a tree, for

instance, does not give us a mere idea of a tree, but involves the judgement that

it exists with a certain shape, size, and position.

The initial furniture of the mind is not a set of disconnected ideas, but a system

of original and natural judgements. ‘They are a part of our constitution, and all

the discoveries of our reason are grounded upon them. They make up what is

called the common sense of mankind; and what is manifestly contrary to any of

those first principles is what we call absurd.’ The common principles which are

the foundation of reasoning include some which have been called in question by

Hume: first, that sensible qualities must have a subject which we call body, and

conscious thoughts must have a subject which we call mind; secondly, that what-

ever begins to exist must have a cause which produced it. Reid’s blunt affirmation

of these principles in the face of Hume’s detailed criticism has a certain air of

dogmatism; but he would respond that principles so fundamental neither require

nor admit of proof.

Reid is willing to go along with Locke in distinguishing between primary and

secondary qualities. But unlike Locke, he thinks that a secondary quality such as

colour is a real quality of bodies: it is not identical with the sensation of colour

which we have, but it is its cause. No one, he says, thinks that the colour of a red

body has changed because we look at it through green glass. It is no objection to

the objectivity of a quality that we can only detect it by its effects: the same is true

of gravity and magnetism. ‘Red’ means what the common man means by it, and

AIBC14 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM264

british philosophy in the eighteenth century

265

its meaning cannot be arbitrarily changed by philosophers. ‘The vulgar have

undoubted right to give names to things which they are daily conversant about;

and philosophers seem justly chargeable with an abuse of language, when they

change the meaning of a common word, without giving warning.’

But while Reid is firm that ordinary language sets the standard for the meaning

of words, he by no means implies that the beliefs of the vulgar are to be preferred

to the results of scientific investigation. On the contrary, Reid regarded himself as

an experimental scientist, and kept himself fully up to date with recent work

about the nature of vision. Indeed, in studying the geometry of visible objects, he

showed great scientific ingenuity, and anticipated the development of non-

Euclidean geometries. What Reid wanted to show was that the realism of the

common man was fully compatible with the pursuit of science, and with the

experimental study of the mind itself.

Reid was one of the ornaments of the eighteenth-century Scottish Enlighten-

ment; he long continued to be influential in his own country, and his importance

has been rediscovered in our own time. But in the mainstream of European

thought his work was overshadowed by the more popular figures of the European

Enlightenment, and his brusque rebuttal of empiricism was superseded by the

more sophisticated critique of Kant.

AIBC14 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM265

the enlightenment

266

XV

THE ENLIGHTENMENT

The

Philosophes

In the eighteenth century, social and political philosophy in France, as in Britain,

was influenced by Locke. But whereas in England, under a constitutional mon-

archy, government was parliamentary if not democratic, and there was religious

toleration for all except Catholics, in France the monarchy was absolute, and once

Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685 only Catholicism was officially

tolerated. However, in the reign of his grandson, Louis XV, a degree of freedom

of thought was permitted, through indolence rather than policy, and a group of

thinkers, the philosophes of the French Enlightenment, created a climate of thought

hostile to the status quo in Church and State. Their manifesto was the Encyclopédie

edited in the 1750s by Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert.

Like Hume, the philosophers of the Enlightenment aimed to establish a science

of human affairs which would match the science which Newton had established

for the physical universe. They saw the power of the Church as an obstacle to the

development of such a science, and they saw it as their mission to replace super-

stition with reason. Already at the end of the seventeenth century Pierre Bayle

had argued in his Dictionnaire historique et critique that in view of the unending

conflicts within both natural and revealed theology, moral teaching should be

made totally independent of religion. A belief in immortality was not necessary

for morality, and there was no reason why there could not be a virtuous com-

munity of atheists.

Voltaire, the best known of the philosophes, agreed with Bayle on the first

point, but not with the second. He thought that the existence of a spiritual,

separable, soul was unprovable and probably false; but he thought that the world

as explained by Newton manifested the existence of God just as much as a watch

shows the existence of a watchmaker. If God did not exist, he said, it would be

necessary to invent him in order to back up the moral law. But Voltaire did not

believe that God had created the world by choice. If he had done so, we would

have to blame Him for such evils as the catastrophic earthquake which struck

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM266

the enlightenment

267

Lisbon in 1755. The world was not a free creation, but a necessary and eternal

consequence of God’s existence. Voltaire, to use the technical term, was not an

atheist but a deist.

In human affairs, too, Voltaire regarded freedom as an illusion, fostered by

historians’ habits of dwelling on the actions of great kings and generals. Voltaire

himself wrote voluminous works of history, emphasizing the importance of the

domestic, artistic, and industrial aspects of past ages. In politics, however, he was

neither a populist nor a democrat; his ideal was the rule of an enlightened despot,

such as his one-time patron, Frederick the Great of Prussia. The liberty he cared

most about was freedom of speech, even though it is not certain that he ever said

‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.’

More significant as a political philosopher was the Baron de Montesquieu,

author of the Persian Letters, a risqué satire on French political and ecclesiastical

life, and The Spirit of the Laws, a vast treatise which seeks to base a theory of the

nature of the state on a mountain of sociological evidence. There are three main

kinds of government: republican, monarchical, and despotic. One cannot single

out one kind of government as everywhere preferable: the government should be

fitted to the climate, the wealth, and the national character of a country. Thus,

republics suit cold climates, and despotism hot climates; freedom is easier to

maintain on islands and in mountains than on level continents; a constitution

suitable for Sicilians would not suit Englishmen, and so on.

Montesquieu, who lived in England for a year, was a great admirer of the

British constitution, in particular because of its separation of powers, which he

saw as a necessary condition of liberty. The legislative, executive, and judicial

branches of government should not be combined in a single person or institu-

tion. If they are separated from each other, they act as checks and balances on

each other, and provide a bulwark against tyranny. Whether or not Montesquieu’s

understanding of the British parliamentary monarchy was accurate, his theory has

had a lasting influence, particularly through its embodiment in the American

constitution.

Rousseau

Of all French philosophers of the eighteenth century the most influential was

Jean Jacques Rousseau, though his influence was greater outside philosophical

circles than among professional philosophers. Like St Augustine, he wrote a book

of autobiographical Confessions; his confessions are more vivid and more detailed

than the Saint’s, and contain more sins, less philosophy, and no prayers. He was

born in Geneva, he tells us, and brought up as a Calvinist; at sixteen, a runaway

apprentice, he became a Catholic in Turin. In 1731 he was befriended by the

Baronne de Warens, with whom he lived for nine years. His first job was as

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM267

the enlightenment

268

secretary to the French ambassador in Venice in 1743; having quarrelled with

him he went to Paris and met Voltaire and Diderot. In 1745 he began a lifelong

relationship with a servant girl, and had by her five children whom he dumped,

one after the other, in a foundling hospital. He achieved fame in 1750 by pub-

lishing a prize-winning essay in which he argued, to the horror of the Encyclo-

paedists, that the arts and sciences had a baneful effect on mankind. This was

followed up, four years later, by a ‘Discourse on Inequality’, which argued that

man was naturally good, and corrupted by institutions. The two works held up

the ideal of the ‘noble savage’ whose simple goodness put civilized man to shame.

In 1754 Rousseau returned to Geneva and became Protestant once more.

After a bitter quarrel with Voltaire, he returned to France and wrote a novel,

La Nouvelle Héloïse, a treatise on education, Emile, and a major work of polit-

ical philosophy, The Social Contract. As a result of the inflammatory doctrines

of these works, he had to flee to Switzerland in 1762 but he was driven out of

Geneva also. In 1776 he was given sanctuary in England by David Hume, who

secured him a pension from King George III. But soon his paranoid ingratitude

became too much even for Hume’s patience, and he returned to France in spite

of the risk of arrest. In his last years he was poor and vilified, and when he died

in 1778 some thought that he had killed himself.

The Social Contract is very readable, as befits a work by a philosopher who was

also a best-selling novelist. Its first words are memorable, though misleading.

‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Many a man believes himself to

be the master of others who is, no less than they, a slave.’ Readers of Rousseau’s

previous works assume that the chains are those of social institutions. Shall we

reject the social order then? No, we are told, it is a sacred right which is the basis

of all other rights. Social institutions, Rousseau now thinks, liberate rather than

enslave.

Like Hobbes, Rousseau believes that society originates when life in the original

state of nature becomes intolerable. A social contract is drawn up to ensure that

the whole strength of the community is enlisted for the protection of each

member’s person and property. Every member has to alienate all his rights to the

community and give up any claim against it. But how can this be done in such a

way that each man, united to his fellows, remains as free as he was before?

The solution is to be found in the theory of the general will. The social

contract creates a moral and collective body, the State or Sovereign People. Every

individual as a citizen shares in the sovereign’s authority, as a subject owes

obedience to the state’s laws. The sovereign people, having no existence outside

that of the individuals who compose it, can have no interest at variance with

theirs: hence it expresses the general will, and it cannot go wrong in its pursuit

of the public good. An individual’s will may go contrary to the general will, but

he can be constrained by the whole body of his fellow citizens to conform to it

– ‘which is no more than to say that it may be necessary to compel a man to be

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM268

the enlightenment

269

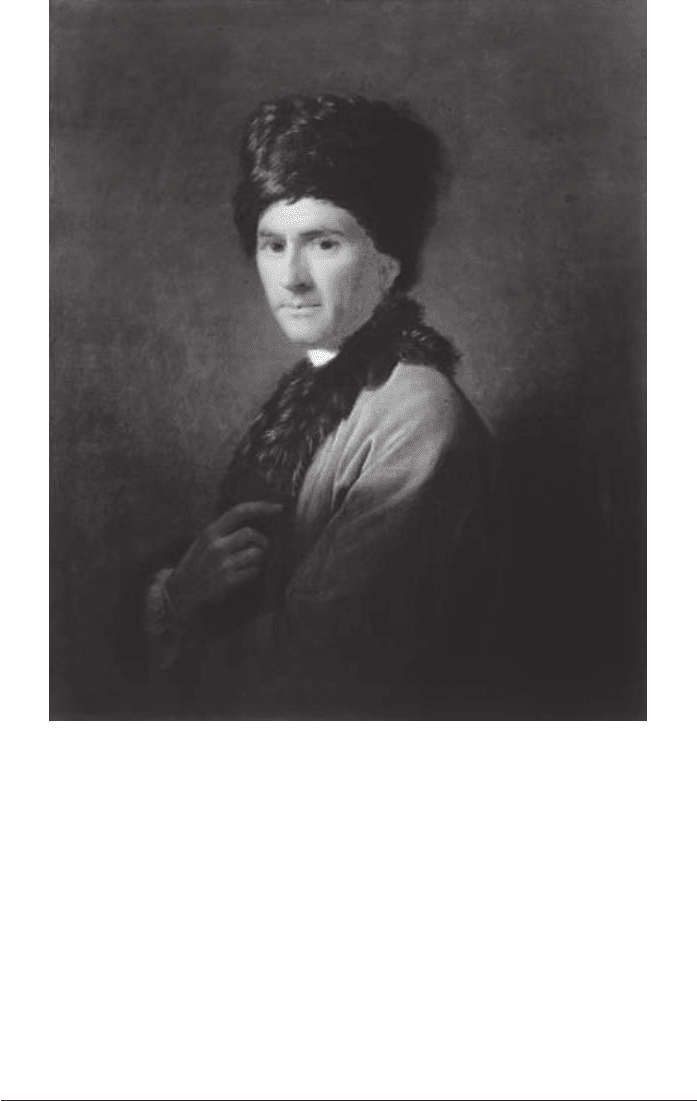

Figure 32 Allan Ramsay’s portrait of J. J. Rousseau.

(National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh)

free’. Under Rousseau’s social contract, men lose their natural liberty to lay hands

on whatever tempts them, but they gain civil liberty, which permits the stable

ownership of property. So men are, genuinely, more free than they were. But the

freedom which Rousseau attributes to the imprisoned malefactor is the rather

rarefied freedom to participate in the expression of the general will.

The sovereign people is an abstract entity: it is not to be identified with any

particular government, of whatever form. Hence, the theory of the general will

is not the doctrine that whatever the government does is right. How, then, is

the general will to be ascertained? By holding a referendum? No: for Rousseau

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM269

the enlightenment

270

‘the general will’ is not the same as ‘the will of all’. ‘There is often considerable

difference between the will of all and the general will. The latter is concerned

only with the common interest, the former with interests that are partial, being

itself but the sum of particular wills.’ The deliberations of a popular assembly,

even when it is unanimous, are by no means infallible. This is because each voter

may suffer from ignorance or be swayed by individual self-interest.

The general will, according to Rousseau, could be ascertained by plebiscite

on two conditions: first, that every voter was fully informed; second, that no two

voters held any communication with each other. The second condition is there to

prevent the formation of groups or parties less than the whole community. For

it is only within the context of the entire state that the differences between the

self-interest of individuals will cancel out and yield the self-interest of sovereign

people. ‘It is therefore essential, if the general will is to be able to express itself,

that there should be no partial society within the State, and that each citizen

should think only his own thoughts.’

The sovereignty of the people is indivisible: if you separate the powers of the

legislative and executive branches you make the sovereign a fantastic creature of

shreds and patches. But sovereignty is also limited: it must be concerned only

with matters of extreme generality. ‘Just as the will of the individual cannot

represent the general will, so, too, the general will changes its nature when called

upon to pronounce upon a particular object.’ Because of this the people, while

the supreme legislative power, has to exert its executive power, which is con-

cerned with particular acts, through an agent, namely the government.

A government is ‘an intermediate body set up to serve as a means of commun-

ication between subjects and sovereign, charged with the execution of the laws and

the maintenance of liberty’. Rulers are employees of the people: the government

receives from the sovereign the orders which it passes on to the people. Like

Montesquieu, Rousseau refuses to specify a single form of government as being

appropriate to all circumstances. But ideally, the form of government, as well

as the individual rulers, should be endorsed by periodic assemblies of the people.

At this point Rousseau’s affection for the procedures of a Swiss canton seem to

have overcome his principle that the sovereign should concern itself only with

general issues.

In spite of his concern with the general will of the people, Rousseau was not a

wholehearted supporter of democracy in practice. ‘Were there such a thing as a

nation of Gods, it would be a democracy. So perfect a form of government is not

suited to men.’ He was thinking, of course, of direct democracy, government

by popular assembly, and his worry was that in such a state the rulers would be

unprofessional and quarrelsome. His favoured form of government is an elective

aristocracy. ‘It is the best and most natural arrangement that can be made that

the wise should govern the masses.’ The great merit of this system is that it

demands fewer virtues than popular government; it does not call for a strict

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM270

the enlightenment

271

insistence on equality, all it requires is a spirit of moderation in the rich and of

contentment in the poor. Naturally, the rich will do most of the governing; they

have more time to spare. But from time to time, a poor man should be elected to

office, to cheer up the populace.

After the rousing rhetoric of ‘Man is born free and is everywhere in chains’ this

seems rather a tame and bourgeois conclusion. None the less, The Social Contract

was seen as a threat by those in power at the time, and was venerated as a Bible

by the revolutionaries who were shortly to take their place. It was not the social

contract of the book’s title which enraged or excited people: as we have seen,

such contract theories were by now two-a-penny. What inflamed readers was the

new notion of the general will.

Looked at soberly, the notion is theoretically incoherent and practically vacuous.

It is not true, as a matter of logic, that if A wills A’s good and B wills B’s good

then A and B jointly wish the good of A and B: to see this we need only consider

the case where A sees as his good the annihilation of B, and B sees as his good

the annihilation of A. What makes Rousseau’s notion useless in practice is the

difficulty of ascertaining what the general will prescribes. As we have seen, he laid

down as conditions for its expression that every citizen should be fully informed

and that no two citizens should be allowed to combine with each other. The

fulfilment of the second condition would demand a total tyranny of the state; the

first condition could never be fulfilled in a community of real human beings.

Revolution and Romanticism

It was, of course, the vacuousness of the notion of the general will which made it

so valuable for political purposes. Eleven years after Rousseau’s death the French

Revolution swept away the regime which had banned The Social Contract. After a

series of moderate and overdue reforms had been secured from King Louis XVI,

the Revolution gathered momentum, abolished the monarchy itself, and executed

the King. The Jacobin party came to power, under Robespierre, and in a reign of

terror guillotined not only the surviving aristocrats of the ancien régime but many

democrats of different colours. Robespierre could proclaim that the will of the

Jacobins was the general will, and that his despotic government was forcing citizens

to be free.

The Revolution could claim to be the offspring not only of Rousseau but also

of the enlightenment philosophes whom he opposed. The revolutionaries did their

best to destroy the Catholic Church not only because of the political and eco-

nomic power it had enjoyed in the ancien régime but also because of their belief

that it was an obstacle to scientific progress. In the Cathedral of Notre Dame an

actress was enthroned as a goddess of Reason. Ex-priests, retrained as deists, were

sent round to country parishes as ‘Apostles of Reason’ (see Plate 14).

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM271

the enlightenment

272

The Revolution that had taken from Rousseau its slogans of liberty and equal-

ity ended by handing over the expression of the general will to Napoleon Bona-

parte, who for a decade enjoyed more power in Europe than any single man since

Charlemagne. But long after the Revolution had blown itself out, Rousseau’s

influence was still to be felt throughout the continent in quite a different way,

through the romantic movement.

It was not the Rousseau of The Social Contract, but the Rousseau of the

Confessions and of the Discourses who shaped the romantic outlook. Rousseau’s

writings sought to revive, in eighteenth-century France, the contempt for the

artificial life of city and court and the cult of rustic crudity which had character-

ised the Cynics of ancient Greece. ‘Sensibility’ was already much in vogue in

France, and the ladies of the court played at being shepherdesses in manicured

gardens at Versailles. But the romantic movement was to turn what had been a

pastime for pampered idlers into the inspiration of a whole way of life.

Romantics did not necessarily take any real interest in the welfare of the rural

workers. They did, however, hold up the real or imagined virtues of peasants

as a mirror to society; and they sought out the forested or mountainous regions

in which the poorest of them lived. On the other hand, romantics scorned the

amenities which can be provided only in urban communities, such as libraries,

universities, and stock-exchanges. In a combination which was comprehensible, if

not inevitable, the preference for the country over the town was at the same time

an assertion of passion against intellect, and a craving for excitement rather than

security.

Romanticism in Britain received its most eloquent expression in the writings of

Wordsworth and Coleridge. In Frost at Midnight, Coleridge tells his baby son:

I was rear’d

In the great city, pent mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander, like a breeze,

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

The philosophy of the English romantics often, as in that passage, resembles

the pantheism of Spinoza, whom they admired. But Wordsworth explored also

Platonic themes: as in the Immortality Ode, which revives the doctrines of recol-

lection and pre-existence.

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM272

the enlightenment

273

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting;

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home.

Elsewhere Wordsworth expresses his worship of Nature in ways which invoke

Neo-Platonic ideas.

I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused.

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean, and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man,

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

This takes us back to the World Soul of Plotinus and of Avicenna.

In the next generation of English poets, John Keats, addressing his Grecian

urn, voiced a sentiment that is sometimes taken as the quintessential credo of

romanticism

When old age shall this generation waste

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st

‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’ – that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

But it would be unfair to characterize romanticism in general as the substitution

of beauty for truth as the supreme value. The romantics had a concern for truth

in their own fashion, insisting that it was more important for emotions to be

genuine than to be comme il faut. And pre-romantics too had placed a high value

on beauty; what the romantics did was to change men’s perceptions of what was

beautiful. In a reaction against the age of reason, order and enlightenment,

romantics felt the attraction of the Middle Ages – not of its philosophy, but of

its irregular architecture and its gloomy ruins. The Gothic revival, which was

to flower in the nineteenth century, began in England in the same decade as

Rousseau’s first Discourse. The last decades of the eighteenth century were the

AIBC15 22/03/2006, 11:06 AM273