Kenny Anthony. An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

244

Figure 29 Baruch Spinoza, portrait by S. van Hoogstraten (1666).

(Photo: akg-images/Erich Lessing)

only sense in which we humans are causes is that we provide the occasion for God

to do the real causing. This is Malebranche’s famous ‘occasionalism’.

If there is no genuine output from mind to body, equally there is no true input

from body to mind. If minds are incapable of moving bodies, bodies are equally

incapable of putting ideas into minds. Our minds are passive, not active, and

cannot create their own ideas. These can only have come from God. If I prick my

finger with a needle, the pain does not come from the needle; it is directly caused

by God. We see all things in God: God is the environment in which minds live,

just as space is the environment in which bodies are located.

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM244

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

245

Malebranche was far from being the first to say that we see the eternal truths by

coming in contact, in some mysterious way, with ideas in the mind of God. But

it was a new move to say that our knowledge of the contingent history of material

and changeable bodies comes directly from God. Descartes, of course, thought

that only God’s truthfulness could show that our empirical knowledge of the

external world was not deceptive. But for Malebranche, there is no such thing as

empirical knowledge of the external world; its existence is a revelation, contained,

along with other truths necessary for salvation, in the Bible.

Like Descartes, therefore, and unlike Spinoza, Malebranche accepts the exist-

ence of finite substances, material and mental. But unlike Descartes and like

Spinoza, he thinks that mind’s relation to God, and matter’s relation to God, are

both much closer than the relation of mind and matter to each other.

Leibniz

Both Malebranche and Spinoza were important influences on the thinking of

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz was born in 1646, the son of a professor of

philosophy at Leipzig university. He started to read metaphysics in early youth,

and by the age of thirteen became familiar with the writings of the scholastics,

to which he remained much more sympathetic than most of his contemporaries.

He studed mathematics at Jena and law at Altdorf, where he was offered, and

refused, a professorship at the age of twenty-one. He entered the service of the

Archbishop of Mainz, and on a diplomatic mission to Paris met many of the

leading thinkers of the day, and came under the influence of Descartes’ succes-

sors. There, in 1676, he invented the infinitesimal calculus, unaware of Newton’s

earlier but as yet unpublished discoveries. On his way back to Germany he visited

Spinoza, and studied the Ethics in manuscript.

From 1676 until the end of his life Leibniz was a courtier to successive Dukes

of Brunswick. He was the librarian of the court library at Wolfenbüttel, and spent

many years compiling the history of the House of Brunswick. He founded learned

societies and became the first president of the Prussian Academy. He was ecu-

menical in theology as well as in philosophy, and made several attempts to reunite

the Christian churches and to set up a European federation. When in 1714 the

elector George of Hanover became King George I of the United Kingdom,

Leibniz was left behind. No doubt he would have been unwelcome in England

because he had quarrelled with Newton over the ownership of the infinitesimal

calculus. He died, embittered, in 1716.

Throughout his life Leibniz wrote highly original work on many branches of

philosophy, but he published only a few comparatively short treatises. His earliest

treatise was the brief Discourse on Metaphysics which he sent in 1686 to Antoine

Arnauld, the Jansenist author of the Port Royal Logic. This was followed in 1695

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM245

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

246

by the New System of Nature. The longest work published in his lifetime was

Essays in Theodicy, a vindication of divine justice in the face of the evils of the

world, dedicated to Queen Charlotte of Prussia. Two of Leibniz’s most import-

ant short treatises appeared in 1714: the Monadology and The Principles of Nature

and of Grace. A substantial criticism of Locke’s empiricism, New Essays on Human

Understanding, did not appear until nearly fifty years after his death. Much of his

most interesting work was not published until the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries.

Since Leibniz kept many of his most powerful ideas out of his published work,

the correct interpretation of his philosophy continues to be a matter of contro-

versy. He wrote much on logic, metaphysics, ethics, and philosophical theology; his

knowledge of all these subjects was encyclopaedic, and indeed he projected a com-

prehensive encyclopedia of human knowledge, to be produced by co-operation

between learned societies and religious orders.

It remains unclear how far Leibniz’s significant contributions to these different

disciplines are consistent with each other, and which parts of his system are

foundation and which are superstructure. But there are close links between parts

of his output which seem at first sight poles apart. In his De Arte Combinatoria

he put forward the idea of an alphabet of human thought into which all truths

could be analysed, and he wanted to develop a single, universal, language which

would mirror the structure of the world. His interest in this was generated partly

by his desire to unite the Christian confessions, whose differences, he believed, were

generated by the imperfections and ambiguities of the various natural languages

of Europe. Such a language would also promote international co-operation between

scientists of different nations.

Since Leibniz never published his philosophy systematically, we have to consider

his opinions piecemeal. In logic he distinguishes between truths of reason and

truths of fact. Truths of reason are necessary, and their opposite is impossible; truths

of fact are contingent and their opposite is possible. Truths of fact, unlike truths

of reason, are based not on the principle of contradiction, but on a different prin-

ciple: the principle that nothing happens without a sufficient reason why it should

be thus rather than otherwise. This principle of sufficient reason was an innovation

of Leibniz, and as we shall see, it was to lead to some astonishing conclusions.

All necessary truths are analytic: ‘when a truth is necessary, the reason for it can

be found by analysis, that is, by resolving it into simpler ideas and truths until the

primary ones are reached’. Contingent propositions, or truths of fact, are not in

any obvious sense analytic, and men can discover them only by empirical invest-

igation. But from God’s viewpoint, they are analytic.

Consider the history of Alexander the Great, which consists in a series of truths

of fact. God, seeing the individual notion of Alexander, sees contained in it all the

predicates truly attributable to him: whether he conquered Darius, whether he

died a natural death, and so on. In ‘Alexander conquered Darius’ the predicate is

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM246

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

247

in a manner contained in the subject; it must make its appearance in a complete

and perfect idea of Alexander. A person of whom that predicate could not be

asserted would not be our Alexander, but somebody else. Hence, the proposition

is in a sense analytic. But the analysis necessary to exhibit this would be an infinite

one, which only God could complete. And while any possible Alexander would

possess all those properties, the actual existence of Alexander is a contingent

matter, even from God’s point of view. The only necessary existence is God’s

own existence.

Leibniz told Arnauld that the theory that every true predicate is contained in

the notion of the subject entailed that every soul was a world apart, independent

of everything else except God. A ‘world apart’ of this kind was what Leibniz later

called a ‘monad’, and in his Monadology Leibniz presented a system which resem-

bles that of Malebranche. But he reached this position by a novel route.

Whatever is complex, Leibniz argued, is made up of what is simple, and what-

ever is simple is unextended, for if it were extended it could be further divided.

But whatever is material is extended, hence there must be simple immaterial,

soul-like entities. These are the monads. Whereas for Spinoza there is only one

substance, with the attributes of both thought and extension, and whereas for

Malebranche there are independent substances, some with the properties of mat-

ter, and some with the properties of mind, for Leibniz there are infinitely many

substances, with the properties only of mind.

Like Malebranche’s substances, Leibniz’s monads cannot be causally affected

by any other creatures. ‘Monads have no windows, by which anything could

come in or go out.’ Because they have no parts, they cannot grow or decay: they

can begin only by creation, and end only by annihilation. They can, however,

change; indeed they change constantly; but they change from within. Since they

have no physical properties to alter, their changes must be changes of mental

states: the life of a monad, Leibniz says, is a series of perceptions.

But does not perception involve causation? When I see a rose, is not my vision

caused by the rose? No, replies Leibniz, once again in accord with Malebranche.

A monad mirrors the world, not because it is affected by the world, but because

God has programmed it to change in synchrony with the world. A good clockmaker

can construct two clocks which will keep such perfect time that they forever strike

the hours at the same moment. In relation to all his creatures, God is such a

clockmaker: at the very beginning of things he pre-established the harmony of

the universe.

All monads have perception, that is to say, they have an internal state which is

a representation of all the other items in the universe. This inner state will change

as the environment changes, not because of the environmental change, but be-

cause of the internal drive or ‘appetition’ which has been programmed into them

by God. Monads are incorporeal automata: when Leibniz wishes to stress this

aspect of them he calls them ‘entelechies’.

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM247

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

248

There is a world of created beings – living things, animals, entelechies and souls –

in the least part of matter. Each portion of matter may be conceived as a garden full

of plants, and as a pond full of fish. But every branch of each plant, every member of

each animal, and every drop of their liquid parts is itself likewise a similar garden

or pond.

We are nowadays familiar with the idea of the human body as an assemblage of

cells, each living an individual life. The monads which – in Leibniz’s system –

corresponded to a human body were like cells in having an individual life-history,

but unlike cells in being immaterial and immortal. Each animal has an entelechy

which is its soul; but the members of its body are full of other living things which

have their own souls. Within the human being the dominant monad is the

rational soul. This dominant monad, in comparison with other monads, has a

more vivid mental life and a more imperious appetition. It has not just perception

but ‘apperception’, that is to say consciousness or reflective knowledge of the inner

state, which is perception. Its own good is the goal, or final cause, not just of its

own activity but also of all the other monads which it dominates. This is all that

is left, in Leibniz’s system, of Descartes’ notion that the soul acts upon the body.

In all this, is any room left for free-will? Human beings, like all agents, finite

or infinite, need a reason for acting: that follows from Leibniz’s ‘principle of

sufficient reason’. But in the case of free agents, he maintains, the motives which

provide the sufficient reason ‘incline without necessitating’. But it is hard to see

how he can make room for a special kind of freedom for human beings. True, in

his system no agent of any kind is acted on from outside; all are completely self-

determining. But no agent, whether rational or not, can step outside the life-

history laid out for it in the pre-established harmony. Hence it seems that Leibniz’s

‘freedom of spontaneity’ – the freedom to act upon one’s motives – is an illusory

liberty.

Leibniz has an answer to this objection, which resembles the thesis of the Jesuit

Molina about the relationship between God and the created universe. Before

deciding to create the world, Leibniz maintains, God surveys the infinite number

of possible creatures. Among the possible creatures there will be many possible

Julius Caesars: and among these there will be one Julius Caesar who crosses the

Rubicon and one who does not. Each of these possible Caesars will act for a

reason, and neither of them will be necessitated (there is no law of logic saying

that the Rubicon will be crossed, or that it will not be crossed). When, therefore,

God decides to give existence to the Rubicon-crossing Caesar he is making actual

a freely-choosing Caesar. Hence, our actual Caesar crossed the Rubicon freely.

But what of God’s own choice to give existence to the actual world we live in,

in contrast to the myriad other possible worlds he might have created? Was there

a reason for that choice, and was it a free choice? Leibniz’s answer is that God

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM248

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

249

chose freely to make the best of all possible worlds; otherwise he could have had

no sufficient reason to create this world rather than another.

Not all things which are possible in advance can be made actual together:

in Leibniz’s terms, A and B may each be possible, but A and B may not be

compossible. Any created world is therefore a system of compossibles, and the

best possible world is the system which has the greatest surplus of good over evil.

A world in which there is free-will which is sometimes sinfully misused is better

than a world in which there is neither freedom nor sin. Hence the evil in the

world provides no argument against the goodness of God. Because God is good,

and necessarily good, he chooses the most perfect world. Yet he acts freely,

because though he cannot create anything but the best, he need not have created

at all.

It is interesting to compare Leibniz’s position here with that of Descartes and

Aquinas. Descartes’ God was totally free: even the laws of logic were the result of

his arbitrary fiat. Leibniz, like Aquinas before him, maintained that the eternal

truths depended not on God’s will but on his understanding; where logic was

concerned God had no choice. Aquinas’ God, though not as free as Descartes’, is

less constrained than Leibniz’s. For, according to Aquinas, though whatever God

does is good, he is never obliged to do what is best. Indeed, for Aquinas, given

God’s omnipotence, the notion of ‘the best of all possible worlds’ is every bit as

nonsensical as that of ‘the greatest of all possible numbers’.

Leibniz’s optimistic theory was memorably mocked by Voltaire in his novel

Candide, in which the Leibnizian Dr Pangloss responds to a series of miseries and

catastrophes with the incantation ‘All is for the best in the best of all possible

worlds’.

The Leibnizian monadology is a baroque effloresence of Cartesian metaphysics.

His work marks the high point of continental rationalism; his sucessors in Ger-

many, especially Wolff, developed a dogmatic scholasticism which was the system

in which Immanuel Kant was brought up, and which was to be the target, in his

maturity, of his devastating criticism. Leibniz’s claim to greatness lies not in his

systematic creations, but in the conceptions and distinctions which he contrib-

uted to many different branches of philosophy, and which became standard coin

among succeeding philosophers.

Several of these – the distinction between different kinds of truths, the notions

of analyticity and compossibility – we have already met. We may add, finally,

Leibniz’s treatment of identity. From the principle of sufficient reason Leibniz

concluded that there were not in nature two beings indiscernible from each

other; for if there were, God would act without reason in treating one differently

from the other. From this principle of the Identity of Indiscernibles, he derives a

definition of the identity of terms. ‘Terms are identical which can be substituted

one for another wherever we please without altering the truth of any statement.’

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM249

continental philosophy in the age of louis xiv

250

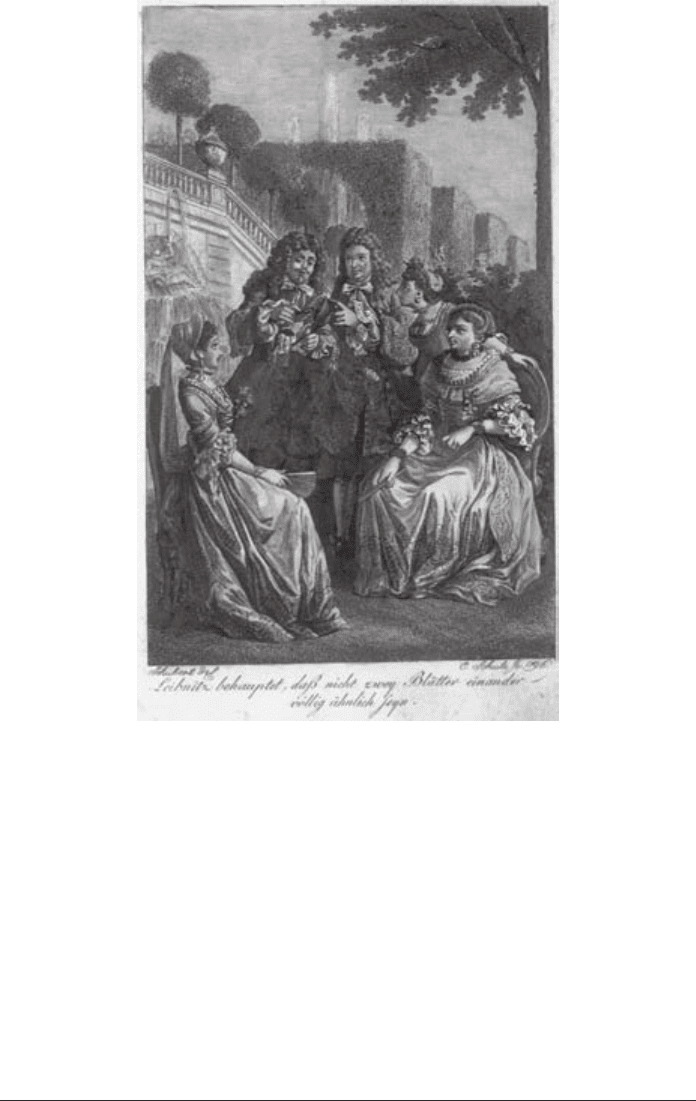

Figure 30 To prove the identity of indiscernibles, Leibniz shows the ladies

of the court that no two leaves are exactly alike.

(Photo: akg-images)

If whatever is true of A is true of B, and vice versa, then A = B. This account of

identity, known as Leibniz’s law, though it is less subtle than that of Locke, has

been taken by most subsequent philosophers as the basis of their discussions of

identity.

AIBC13 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM250

british philosophy in the eighteenth century

251

XIV

BRITISH PHILOSOPHY IN

THE EIGHTEENTH

CENTURY

Berkeley

In 1715 King Louis XIV of France died. A year earlier Queen Anne, the last of

the Stuart monarchs of England, had died, and on her death, the English crown

was given to the dynasty of Hanover, in order to preserve the Protestant succes-

sion. The Hanoverian King Georges were able to maintain their throne against

attempts by the son and grandson of James II (the ‘Old and Young Pretenders’)

to restore the Stuart line. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, in the reign

of Anne, the crowns of England and Scotland were united; and those of England

and Ireland were united at the end of the century, in the reign of George III.

Thus was formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. As it turned

out, the ablest philosophers writing in English in the eighteenth century were

Irish or Scottish, though all of them saw themselves as carrying on the tradition

of the Englishman John Locke.

George Berkeley was born in Ireland in 1685, and after graduating from

Trinity College, Dublin, he published a number of short but important philo-

sophical works. His New Theory of Vision appeared in 1709, Principles of Human

Knowledge in 1710, and Three Dialogues in 1713. In 1713 he came to England

and became a member of the circle of Swift and Pope. He travelled in Europe

and America, and at one time planned to set up a missionary college in the

Bermudas. He became Bishop of Cloyne in 1734 and in 1753 died in retirement

in Oxford, where he is buried in Christ Church Cathedral. A College at Yale and

a university town in California are named after him.

Berkeley’s starting point in philosophy is Locke’s theory of language. Accord-

ing to Locke words have meaning by standing for ideas, and general words, such

as sortal predicates, correspond to abstract general ideas. The ability to form such

ideas is the most important difference between humans and dumb animals.

AIBC14 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM251

british philosophy in the eighteenth century

252

Berkeley extracts from Locke’s Essay two different accounts of the meanings

of general terms. One, which we may call the representational theory, is that a

general idea is a particular idea which has been made general by being made to

stand for all of a kind, in the way in which a geometry teacher draws a particular

triangle to represent all triangles. Another, which we may call the eliminative

theory, is that a general idea is a particular idea which contains only what is

common to all particulars of the same kind: the abstract idea of man eliminates

what is peculiar to Peter, James, and John, and retains only what is common to

them all. Thus, the abstract idea of man contains colour, but no particular colour,

stature, but no particular stature, and so on. There is one passage in which Locke

combines features of the two theories, where he explains that it takes pains and

skill to form the general idea of a triangle ‘for it must be neither oblique nor

rectangle, neither equilateral, equicrural nor scalenon; but all and none of these

at once’.

Berkeley protests that this is absurd. ‘The idea of man that I frame myself must

be either of a white, or a black, or a tawny, a straight, or a crooked, a tall, or a

low, or a middle-sized man. I cannot by any effort of thought conceive the

abstract idea.’ If by ‘idea’ Berkeley here means an image, his criticism seems

mistaken. Mental images do not need to have all the properties of that of which

they are images, any more than a portrait on canvas has to represent all the

features of the sitter. A dress pattern need not specify the colour of the dress,

even though any actual dress must have some particular colour. A mental image

of a dress of no particular colour is no more problematic than a non-specific dress

pattern. There would, indeed, be something odd about an image which had all

colours and no colours at once, as Lock’s triangle had all shapes and no shape at

once. But it is unfair to judge Locke’s account by this single rhetorical passage.

Where Locke really goes astray is in thinking that the possession of a concept

(which is standardly manifested by the ability to use a word) is to be explained by

the having of images. To use a figure, or an image, to represent an X, one must

already have a concept of an X. Moreover, concepts cannot be acquired simply by

stripping off features from images. Apart from anything else, there are some

concepts to which no image corresponds: logical concepts, for instance, such as

those corresponding to the words ‘all’ and ‘not’. There are other concepts which

could never be unambiguously related to images, for instance arithmetical con-

cepts. One and the same image may represent four legs and one horse, or seven

trees and one copse.

Berkeley was correct, against Locke, in thinking that one can separate the

mastery of language from the possession of abstract general images; but his own

alternative solution, that names ‘signify indifferently a great number of particular

ideas’, was equally mistaken. Once concept-possession is distinguished from image-

mongering, mental images become philosophically unimportant. Imaging is no

more essential to thinking than illustrations are to a book. It is not our images

AIBC14 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM252

british philosophy in the eighteenth century

253

which explain our possession of concepts, but our concepts which confer mean-

ing on our images.

Berkeley’s arguments against abstract ideas are most fully presented in his

Principles of Human Knowledge; his other criticisms of Locke are most elegantly

developed in his Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous. Berkeley’s own

philosophical system is encapsulated in the motto esse est percipi: for unthinking

things, to exist is nothing other than to be perceived.

In the Three Dialogues, the system is developed in four stages. First, Berkeley

argues that all sensible qualities are ideas. Secondly, he demolishes the notion of

inert matter. Thirdly, he proves the existence of God. Fourthly, he reinterprets

ordinary language to match his own metaphysics, and defends the orthodoxy of

his system. Berkeley’s language is economical, lucid, and stylish, and the task of

distinguishing between his sound and unsound arguments is not a difficult one,

so that the Dialogues provide an ideal text for a beginners’ class in philosophy.

In the first dialogue Berkeley argues for the subjectivity of secondary qualities,

using Locke as an ally; then he turns the tables against Locke by producing

parallel arguments for the subjectivity of primary qualities. Starting from Locke’s

premiss that only ideas are immediately perceived, Berkeley reaches the conclusion

that no ideas, not even those of primary qualities, are resemblances of objects.

The two characters in the dialogue are Hylas, the Lockean friend of matter,

and Philonous, the Berkeleian spokesman for idealism. Hylas turns out, right

from the start, to be a very faint-hearted friend of matter, because he accepts

without argument the premiss that we do not perceive material things in them-

selves, but only their sensible qualities. ‘Sensible things,’ he says, ‘are nothing else

but so many sensible qualities.’ Material things may be inferred, but they are not

perceived. ‘The senses perceive nothing which they do not perceive immediately;

for they make no inferences.’

Hylas does, however, maintain the objectivity of sensible qualities, and in order

to destroy this position Berkeley makes Philonous expound the line of argument

used by Locke to show the subjectivity of heat. There are, as we have seen, a

number of fallacies in the argument. It is in the mouth of Hylas that Berkeley

cunningly places many of the false moves, as in the following passage:

Phil. Heat then is a sensible thing?

Hyl. Certainly.

Phil. Doth the reality of sensible things consist in being perceived? or is it

something distinct from their being perceived, and that bears no relation

to the mind?

Hyl. To exist is one thing, and to be perceived is another.

Phil. I speak with regard to sensible things only. And of these I ask, whether

by their real existence you mean a substance exterior to the mind, and

distinct from their being perceived?

AIBC14 22/03/2006, 11:05 AM253